CHAPTER NINE

Telomeres Weigh In: A Healthy Metabolism

Your telomeres care how much you weigh—but not as much as you might imagine. What really appears to matter to telomeres is your metabolic health. Insulin resistance and belly fat are your real enemies, not the pounds on the scale. Dieting affects telomeres, both for good and for ill.

My (Elissa’s) friend Peter is a genetic researcher and athlete who competes in Olympic-distance triathlons. He is muscular and burly, and his handsome face glows from his daily exercise. Peter has a huge appetite, but he works hard to keep himself from eating too much. I have spent a lot of time studying the psychology of eating, so I asked him what it’s like to think so much about not eating:

I would have been an awesome hunter-gatherer. I can sniff out food in a second, especially sweets. At work, it’s a joke: when food appears, so does Peter. I know where people will put food out—one person has a candy jar she fills periodically, another puts a plate of food out on a counter near her office, and lots of people put snacks or leftovers from parties or their kids’ Halloween stash on the table in the kitchen.

I try to avoid seeing the food. When I meet with the woman who has the candy bowl, I try hard not to look at it (she’s my boss, and I should be listening to her, but sometimes I’m thinking about not looking at the candy). When I get up to go to the bathroom, I choose a route that won’t take me near the kitchen. But that means I can’t even pee without thinking about food: Will I go by the kitchen to see if something is there? Or will I be strong and take a different route? I have to answer that question pretty much every time I leave my desk, because it’s so easy to choose a route that will take me by a place where there might be food.

My plans to eat well don’t always work. For instance, I often bring a healthy salad to work, but I don’t always eat it, because I have to store it in the kitchen. I’ll be on my way to get a salad, and get intercepted by the pound cake that someone put on the kitchen table. I end up eating a pound of cake—isn’t that why they call it a pound cake?—while the salad sits, wilting and forgotten.

As Peter has discovered, it’s hard work to think about food all the time, and even harder to lose weight. However, there is hopeful news for Peter and everyone else who struggles with weight, diet, and stress: It is not necessary, or even healthy, to think so much about food and caloric intake. That’s because your telomeres care about your weight, but not as much as you might think.

IT’S THE BELLY, NOT THE BMI

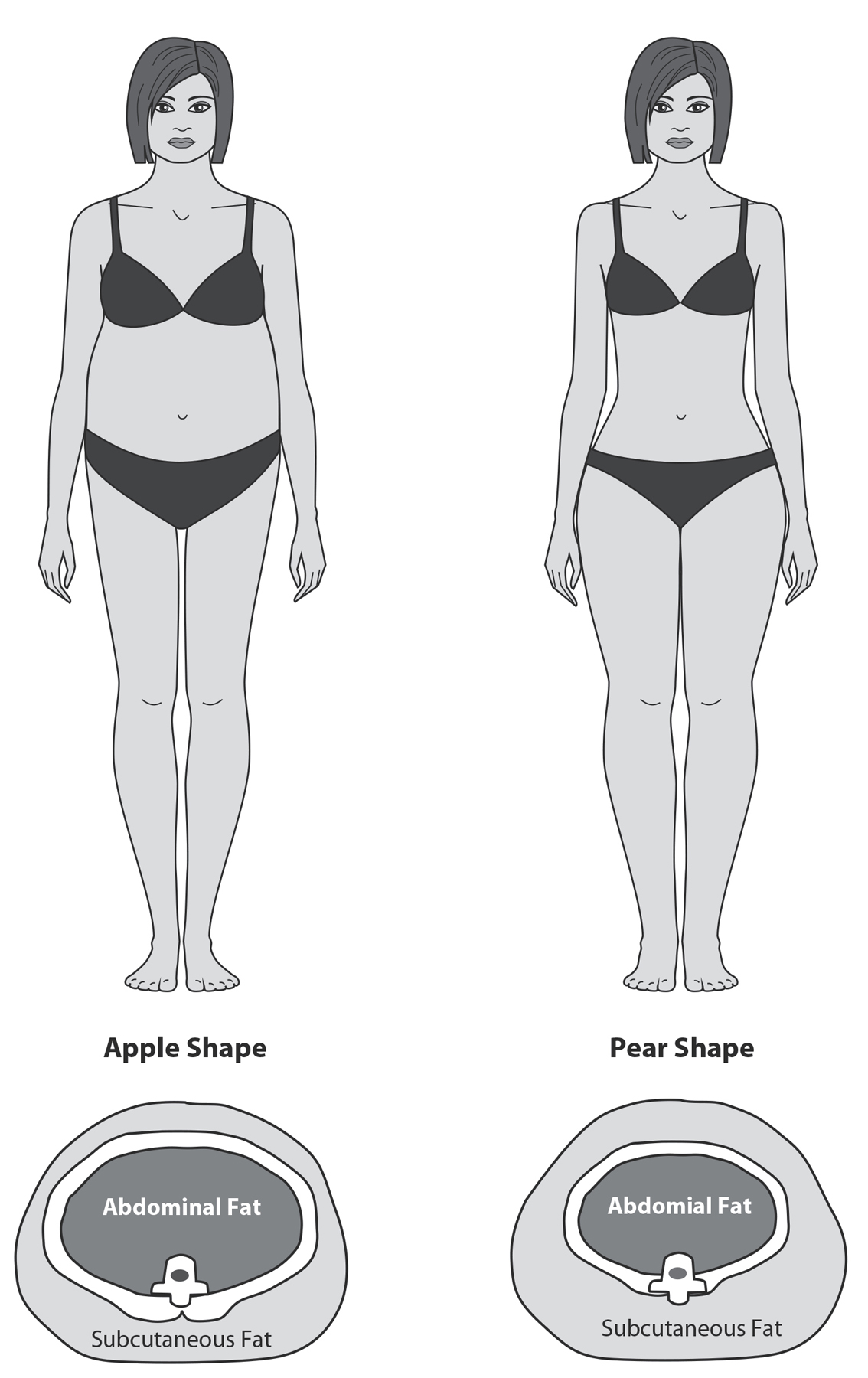

Does eating too much shorten your telomeres? The quick and easy answer is yes. The effect of excess weight on telomeres is real—but it’s not nearly as striking as the relationship between, say, depression and telomeres (which is around three times larger).1 The weight effect is small and probably not directly causal. This finding may come as a surprise to people like Peter, who devote a huge chunk of their mental resources to the effort of eating less. It may be a bit shocking to everyone who’s heard the message that weight loss is the most urgent goal in public health. Yet being overweight (and not obese) is, surprisingly, not linked strongly to shorter telomeres (nor is it strongly linked to mortality). Here’s the reason: weight is a crude stand-in measure for what really matters, which is your metabolic health.2 Most obesity research relies on the measure of body mass index (BMI, a measure of weight by height), but this does not tell us much about what really matters—how much muscle versus body fat we have, and where the fat is stored. Fat stored in the limbs (subcutaneously, so under the skin but not in the muscle) is different and maybe even protective, while fat stored deep inside, in the belly, liver, or muscles, is the real underlying threat. We are going to show you what it means to have poor metabolic health and show you why dieting may not be the way to get healthier.

Growing up, Sarah impressed her friends and family with her appetite. “I’d eat an Italian sub sandwich as an after-school snack, washed down by two glasses of sweet iced tea, and I’d never gain weight,” she recalls wistfully. Sarah ate her way through high school and college; throughout a charmed early adulthood, she was slim. Until, suddenly, she wasn’t. She was eating the same things and exercising the same amount (which was very little). Her upper body and legs were still trim, but her pants stopped fitting. Sarah had developed a belly. “I look like a strand of spaghetti with a meatball in the middle,” she says now. She’s worried, because both her parents take medication for high levels of bad cholesterol. After three decades of feeling effortlessly healthy, Sarah is wondering if she is going to join her parents in line at the pharmacy.

She’s right to be worried, and it’s not just her cholesterol levels that are at stake. Sarah’s body type, where the weight is overrepresented at the belly, is closely associated with poor metabolic health. This is true no matter how much you weigh. It’s true for people who carry a huge beer belly, and it’s true for Sarah, whose BMI is normal but whose waist circumference is bigger than her hips.

When we say a person has poor metabolic health, we generally mean that he or she has a package of risk factors: belly fat, abnormal cholesterol levels, high blood pressure, and insulin resistance. Have three or more of these risk factors and you get labeled with “metabolic syndrome,” a precursor to heart problems, cancer, and one of the greatest health threats of the twenty-first century: diabetes.

Figure 22: Telomeres and Belly Fat. Here you see what it means to have excessive fat around the waist, an apple shape (reflecting high intra-abdominal fat, measured by a greater waist-to-hip ratio, or WHR), versus more fat in the hips and thighs, a pear shape (smaller WHR). Subcutaneous fat, found under the skin and in limbs, carries fewer health risks. High intra-abdominal fat is metabolically troublesome and indicates some level of poor glucose control or insulin resistance. In one study, greater WHR predicts 40 percent greater risk for telomere shortening over the next five years.3

BELLY FAT, INSULIN RESISTANCE, AND DIABETES

Diabetes is a global public health emergency. The list of its long-term effects is long and chilling: heart disease, stroke, vision loss, and vascular problems that can require amputations. Worldwide, more than 387 million people—that’s nearly 9 percent of the global population—have diabetes. That includes 7.3 million in Germany, 2.4 million in the United Kingdom, 9 million in Mexico, and a colossal 25.8 million people in the United States.4

Here’s how type 2 diabetes develops: in a healthy person, the digestive system breaks food down into glucose. The beta cells in the pancreas make a hormone, insulin, which is released into the bloodstream and allows glucose to enter the body’s cells to be used as fuel. In a wonderfully tidy system, insulin binds to receptors on the cells, like a key fitting into a lock. The lock turns, the door opens, and glucose can enter the body’s cells. But too much belly or liver fat can cause your body to become insulin resistant, meaning that cells don’t respond to insulin the way they should. Their “locks”—the insulin receptors—gum up and stick; the key no longer fits as well. It’s harder for glucose to enter the cells. The glucose that can’t get in through the door remains in the bloodstream. Glucose builds up in the blood even as your pancreas churns out more and more insulin. Type 1 diabetes is related to failure of the beta cells in the pancreas; they can’t produce enough insulin. You’re at risk for metabolic syndrome. And if your body can’t keep glucose in the normal range, diabetes results.

HOW SHORT TELOMERES AND INFLAMMATION CONTRIBUTE TO DIABETES

Why do people with belly fat have more insulin resistance and diabetes? Poor nutrition, inactivity, and stress are all associated with belly fat and higher levels of blood sugar. But people with belly fat develop shorter telomeres over the years,5 and it’s very possible that these short telomeres worsen the insulin resistance problem. In a Danish study of 338 twins, short telomere length predicted increases in insulin resistance over twelve years. Within twin pairs, the twin with shorter telomeres developed higher insulin resistance.6

There’s also a well-established connection between short telomeres and diabetes. People afflicted with inherited short telomere syndromes are much more likely to develop diabetes than the rest of the population. Their diabetes comes on early and strong. Other evidence comes from Native Americans, who are at a high risk of diabetes for a variety of reasons. When an Native American has short telomeres, he or she is twice as likely to develop diabetes over the course of five years than other members of this ethnic group with longer telomeres.7 A meta-analysis across studies of around seven thousand people shows that short blood cell telomeres predict future onset of diabetes.8

We even have a glimpse into the mechanism that causes diabetes and can see what’s happening in the pancreas. Mary Armanios and her colleagues have shown that when a mouse’s telomeres are shortened throughout its body (through a genetic mutation), its pancreas’s beta cells are not able to secrete insulin.9 And the stem cells in the pancreas become exhausted; they run out of telomere length and can’t replenish the damaged pancreatic beta cells that should have been doing the work of insulin production and regulation. These cells die off. Type 1 diabetes steps in and begins its malevolent work. In the more common type 2 diabetes, there is some beta cell dysfunction, and so short telomeres in the pancreas may play some role there as well.

In an otherwise healthy person, the pathway from belly fat to diabetes may also be traveled via our old enemy, chronic inflammation. Abdominal fat is more inflammatory than, say, thigh fat. The fat cells secrete proinflammatory substances that damage the cells of the immune system, making them senescent and shortening their telomeres. (Of course, one hallmark of senescent cells is that they can’t stop sending out proinflammatory signals of their own. It’s a vicious cycle.)

If you have excess belly fat (and more than half the adults in the United States do), you may be wondering how you can protect yourself—from inflammation, from short telomeres, and from metabolic syndrome. Before you go on a diet to reduce belly fat, read the rest of this chapter; you may decide that a diet will only make things worse. And that’s fine, because soon we will suggest some alternate ways to improve your metabolic health.

DIETING IS DISAPPOINTING (WHAT A RELIEF)

There is a relationship between dieting, telomeres, and your metabolic health. But as in all things related to weight, it’s complicated. Here are some results of research into weight loss and telomeres:

Weight loss leads to a slowdown in the normal attrition rate of telomeres.

Weight loss leads to a slowdown in the normal attrition rate of telomeres.

Weight loss has no effect on telomeres.

Weight loss has no effect on telomeres.

Weight loss encourages telomeres to lengthen.

Weight loss encourages telomeres to lengthen.

Weight loss leads to shorter telomeres.

Weight loss leads to shorter telomeres.

It’s a mind-bending set of findings. (In that final study, people who underwent bariatric surgery had shorter telomeres one year after their procedure, though this effect was possibly from the physical stress of the surgery.)10

We think that these mixed results are telling us that, once again, it’s not really the weight that matters. Weight loss is only a crude stand-in for positive changes to underlying metabolic health. One of those changes is the loss of belly fat. Lose weight overall, and you’ll inevitably take a bite out of that “apple,” and this may be more true if you are increasing your exercise rather than just reducing calories. Another positive change is improved insulin resistance. One study followed volunteers for ten to twelve years; as the people in the study gained weight (as people tend to do), their telomeres got shorter. But then the researchers examined which mattered more, weight gain or the insulin resistance that often comes with it. It was insulin resistance that carried the weight, so to speak.11

This idea—that improving your metabolic health is more important than losing weight—is vital, and that’s because repeated dieting takes a toll on your body. There are some internal “push back” mechanisms that makes it hard for us to keep weight off. Our body has a set point that it defends, and when we lose weight, we also slow our metabolism in an effort to regain the weight (“metabolic adaptation”). While this is well known, we didn’t know how dramatic this adaptation could be. There is a tragic lesson here from the brave volunteers who have joined the reality TV show The Biggest Loser. For this show, very heavy people compete to lose the most pounds over 7.5 months, using exercise and diet. Dr. Kevin Hall and his colleagues from the National Institutes of Health decided to examine how this rapid massive weight loss affected their metabolism. At the end of the show, they had lost 40 percent of their weight (around 58 kg). Hall checked their weight and metabolism again six years later. Most had regained weight, but they kept an average of 12 percent weight loss. Here is the hard part: at the end of the program, their metabolism had slowed so that they were burning 610 fewer calories per day. By six years, despite weight regain, their metabolic adaptations had become even more severe, where they were burning around 700 calories fewer than their baseline.12 Ouch. While this is an example of extreme weight loss, this metabolic rate slowing happens to a lesser extent whenever we lose weight, and, apparently, even when we regain it.

In the phenomenon known as weight cycling (or “yo-yo dieting”), dieters gain pounds and lose them, and gain and lose, and so on. Fewer than 5 percent of people who are trying to lose weight can stick to a diet and maintain the weight loss for five years. The remaining 95 percent either give up or become weight cyclers. Weight cycling has become a way of life for many of us, especially women; it’s what we talk about; it’s how we laugh together. (An example: “Inside me there’s a skinny woman crying to get out, but I can usually shut her up with cookies.”) Yet weight cycling appears to shorten our telomeres.13

Weight cycling is so unhealthy, and also so common, that we feel strongly that everyone should understand it. Weight cyclers restrict themselves for a while and then, when they fall off the wagon, tend to indulge in treats and other unhealthy foods. This intermittent cycling between restriction and indulgence is a real problem. What happens to animals when they get junk food all the time? They overeat and get obese. But when you withhold junk food most of the time, giving it to them only every few days, something even more disturbing happens. The rats’ brain chemistry changes; the brain’s reward pathways start to look like the brains of people who are suffering from drug addiction. When the rats don’t get their sugary, chocolaty rat junk food, they develop withdrawal symptoms, and their brains release the stress chemical CRH (short for corticotropin-releasing hormone). The CRH makes the rats feel so bad that they are driven to seek the junk food, to get relief from their stressed state of withdrawal. When the rats finally do get the chocolaty stuff, they eat it as if they will never have the chance again. They binge.14

Sound like anyone you know? Or like Peter eating pound cake on his way to eat a healthy salad for lunch? Studies of obese people suggest a similar compulsive aspect of overeating, with dysregulation in the brain’s reward system.

Dieting can create a semiaddictive state, and it’s also just plain stressful. Monitoring calories causes cognitive load, meaning that it uses up the brain’s limited attention and increases how much stress you feel.15

Think of Peter, spending years trying to eat fewer sweets and calories. Obesity researchers have a name for this kind of long-term dieting mentality: cognitive dietary restraint. Restrainers devote a lot of their time to wishing, wanting, and trying to eat less, but their actual caloric intake is no lower than people who are unrestrained. We asked a group of women questions such as “Do you try to eat less at mealtimes than you like to eat?” and “How often do you try not to eat between meals because you are watching your weight?” The women who answered in ways that revealed a high level of dietary restraint had shorter telomeres than carefree eaters, regardless of how much they weighed.16 It’s just not healthy to spend a lifetime thinking about eating less. It’s not good for your attention (a precious limited resource), it’s not good for your stress levels, and it’s not good for your cell aging.

Instead of dieting by restricting calories, focus on being physically active and eating nutritious foods—and in the next chapter we will help you choose the foods that are best for your telomeres and overall health.

EXTREME CALORIC RESTRICTION: IS IT GOOD FOR TELOMERES?

You’re in a cafeteria, standing in line with your tray. When you get to the front of the line, you notice that everyone is using pairs of tongs to select tiny morsels of food, which they carry over to a scale and weigh carefully. Once they are satisfied with the number of grams of food they have chosen, they take their trays—which bear much less food than you’d normally choose for yourself—to a table and sit down. You join them and watch them eat their meager lunches. When their plates are empty, they say, “Still a bit hungry,” and smile.

Why are these people weighing out small portions of food? Why are they smiling when they’re hungry? This is a thought exercise—no such cafeteria exists in the real world—but it reflects the habits of people who believe that by restricting their calories to 25 or 30 percent less than a normal healthy intake, they will live longer. People who practice caloric restriction teach themselves to have a different reaction to hunger. When they feel the pang of an empty stomach, they don’t feel stressed or unhappy. Instead, they say to themselves, Yes! I’m reaching my goal. They are incredibly good at planning and thinking about the future. For example, a caloric restriction practitioner in one of our studies was eagerly organizing his 130th birthday, even though he was only around sixty years old at the time.20

If only these people were worms. Or mice. There is little doubt that extreme caloric restriction extends the longevity of various lower species. In at least some breeds of mice on restricted diets, telomeres appear to lengthen. They also have fewer senescent cells in the liver, an organ that is one of the first places senescent cells will build up.21 Caloric restriction can improve insulin sensitivity, too, and reduce oxidative stress. But it’s harder to pinpoint the effects of caloric restriction on larger animals. In one study, monkeys who ate 30 percent fewer calories than normal had a longer healthspan and longer life—but only when compared to a control group of monkeys who ate a lot of sugar and fat. In a second study, monkeys on a similarly restricted diet were compared to monkeys who ate normal portions of healthy food. Those monkeys did not have more longevity, though they stayed in the healthspan a bit longer. Adding to the uncertainty is that in both studies, the monkeys ate in solitude. Monkeys are highly social animals; in the wild, they eat together. Having them eat in circumstances that were abnormal, and quite possibly stressful, could have affected the outcome in ways we don’t yet understand.

For now, it looks as if caloric restriction has no positive effect on human telomeres. Janet Tomiyama, now a psychology professor at UCLA, conducted a study during her postdoctoral fellowship at UCSF. She managed to round up a group of people from across the United States who were successful at long-term caloric restriction for an intensive study where she also examined telomeres in different blood cell types. (As you may imagine, such people are rare.) To our surprise, their telomeres weren’t any longer than the normal or even the overweight control group. In fact, their telomeres tended to be slightly shorter in their peripheral mononuclear blood cells, which are types of immune cells that include the T-cells. Another study looked at rhesus monkeys who were restricted to 30 percent fewer calories than a normal rhesus monkey diet. The researchers measured telomere length in various tissues—not just blood, which is the typical source of telomere measurements, but also in fat and muscle. Once again, there were no differences in telomere length in the calorie-restricted monkeys—not in any of the cell types.

Thank goodness. Most people can’t practice extreme calorie restriction, and few people want to. As one of our friends said, “I’d rather eat good dinners until I’m eighty than starve until I’m one hundred.” He’s got a point. You do not have to suffer to eat in a way that is good for your telomeres and good for your healthspan. To learn more, turn to the next chapter.

TELOMERE TIPS

Telomeres tell us not to focus on weight. Instead, use your level of belly protrusion and insulin sensitivity as an index of health. (Your doctor can measure your insulin sensitivity by testing your fasting insulin and glucose.)

Telomeres tell us not to focus on weight. Instead, use your level of belly protrusion and insulin sensitivity as an index of health. (Your doctor can measure your insulin sensitivity by testing your fasting insulin and glucose.)

Obsessing about calories is stressful and possibly bad for your telomeres.

Obsessing about calories is stressful and possibly bad for your telomeres.

Eating and drinking low-sugar, low-glycemic-index food and beverages will boost your inner metabolic health, which is what really matters (more than weight).

Eating and drinking low-sugar, low-glycemic-index food and beverages will boost your inner metabolic health, which is what really matters (more than weight).