CHAPTER THIRTEEN

Childhood Matters for Life: How the Early Years Shape Telomeres

Childhood exposures to stress, violence, and poor nutrition affect telomeres. But there are factors that appear to protect vulnerable children from damage—including sensitive parenting and mild “good stress.”

In the year 2000, Harvard psychologist and neuroscientist Charles Nelson walked into one of Romania’s notorious orphanages, a legacy of the brutal policies of the Nicolae Ceauşescu regime. The institution housed about four hundred children, all segregated by age as well as by disability. There was a ward full of children with untreated hydrocephalus, a disorder in which the skull expands to accommodate excess fluid, and spina bifida, a defect of the spinal cord and the bones along the spine. There was an infectious disease ward that housed children with HIV and children with syphilis so advanced that it had gone to the brain. On this same day, Nelson entered a ward full of supposedly healthy children who were around two or three years old. One of these children—they’d all been given similar haircuts and clothing, so it was hard to identify them by gender—stood in the middle of the floor, pants soaking wet, sobbing. Nelson asked one of the caregivers why the child was crying.

“His mother abandoned him here this morning,” she said. “He’s been crying all day.”

With so many children under their care, the staff had no time for comforting or soothing. Leaving newly abandoned children alone was a way for the staff to quickly extinguish unwanted behaviors like crying. Babies and toddlers were left in their cribs for days at a time, with nothing to do but stare up at the ceiling. When a stranger walked by, the children would reach their arms out through the crib railings, begging to be held. Although the children were adequately fed and sheltered, they received almost no affection, no stimulation. As Nelson and his team built a lab inside the orphanage to study the effects of early childhood neglect on the developing brain, they had to establish a behavior rule of their own to avoid adding to the residents’ distress: No crying in front of the children.

What Nelson and his colleague, Dr. Stacy Drury, learned from studies at the orphanage is both heartbreaking and hopeful. Early childhood neglect shortens telomeres—but there are interventions that can help neglected or traumatized children, if we can catch them at a young age. Although the conditions of the orphanages in Romania have improved generally, there are still around seventy thousand orphans and fewer international adoptions to rescue them.1 Institutional care of children is an ongoing global crisis. War, along with diseases like HIV and Ebola, rob children of their parents and have left an estimated eight million children currently housed in orphanages around the world. We can’t afford to turn away from this story.2

It is also a story that may have relevance inside our own homes. Telomere knowledge can guide our actions as parents, illuminating a path to raising our children in a way that is healthy for their telomeres. For adults who experienced trauma as children, understanding the long-lasting cellular effects of the past can offer motivation for treating telomeres with tender care now, in the present.

TELOMERES TRACK CHILDHOOD SCARS

When you were growing up, did you have a parent who drank too much? Was anyone in your family depressed? Were you often afraid that your parents would humiliate you or even hurt you?

In a study that painted a disturbing portrait of childhood in the United States, seventeen thousand people were asked to answer a list of ten questions much like the ones above. Around half the sample had experienced at least one such adverse event or situation in childhood, and 25 percent had experienced two or more. Six percent experienced at least four. Substance abuse in the family was most common, then sexual abuse and mental illness. Adverse childhood events happen across all levels of incomes and education. Worse, the more events that a person ticked off on the list, particularly if the person had four or more, the more likely the person was to have health problems in adulthood: obesity, asthma, heart disease, depression, and others.3 Those with four or more adverse events were twelve times more likely to have attempted suicide.

Biological embedding is the name for the effects of childhood adversity that lodge themselves in the body. When telomeres are measured in healthy adults who were exposed to adverse childhood events, a dose-response relationship is often seen. The more traumatic events that a person experienced back then, the shorter their telomeres as an adult.4 Shorter telomeres are one way that early adversity embeds itself in your cells.

Those short telomeres could have searing effects on a child. If you take a group of young children with shorter telomeres and peer inside their cardiovascular systems a few years later, you’ll find that they are more likely to have greater thickening of the walls of their arteries. These are kids we’re talking about here—and for them, short telomeres could mean a higher risk of early cardiovascular disease.5

That damage may begin at a very young age, though it can be halted or possibly reversed if children are rescued from adversity early enough. Charles Nelson and his team compared the children living in Romanian orphanages to ones who’d left the orphanages for quality care in foster homes. The more time the children had spent in the orphanage, the shorter their telomeres.6 Many of the orphans showed low levels of brain activity during EEG scans. “Instead of a hundred-watt light bulb,” Nelson has said, “it was a forty-watt light bulb.”7 Their brains were measurably smaller, and their average IQ was 74, which put them on the borderline of mental retardation. For most of the institutionalized children, their language was delayed and in some cases disordered. Their growth was stunted; they had smaller heads; and they had abnormal attachment behavior, which affects the ability to form lasting relationships. But, says Nelson, “the kids in foster care were showing dramatic recoveries.” The children who’d been moved to foster care showed remarkable gains although they had not completely caught up to the children who had never been in orphanages at all; for example, although their IQ was still below that of the never-institutionalized children in the study, it was ten or more points higher than children in the institution.8 There seemed to be a critical period of brain development: “The kids placed in foster care before age two had improvements in many domains that were better than kids placed after age two,” Nelson says.9 Drury, Nelson, and their team have continued to track these children over the years—and even now, the adolescents who lived at the orphanage as children experience telomere shortening at an accelerated rate.

What about the telomeres of children who are exposed to conditions that, while violent, are not quite so brutal? Scientists Idan Shalev, Avshalom Caspi, and Terri Moffitt, of Duke University, took cheek swabs from five-year-old British children. (Telomeres can be obtained from buccal cells, which live in cheeks.) Five years later, when the children were ten, they swabbed the children’s cheeks again. During the five years, the researchers asked the children’s mothers about whether their children had been bullied, hurt by someone in their household, or witnessed domestic violence between the parents. The children who had been exposed to the most violence had the greatest telomere shortening over the five years.10 Maybe this effect on children is short-lasting, or it can change if their life circumstances improve. We hope so. But studies of adults in which people are asked to recall whether they had early adversity also show that those who did have early adversity have shorter telomeres, revealing what may be a lifelong imprint of childhood adversity inside them.11 In a large study of adults in the Netherlands, reporting several traumatic events as a child was one of the few predictors of having a greater rate of shortening as an adult.12 In addition, childhood trauma, particularly maltreatment, has been related to greater inflammation and a smaller prefrontal cortex.13

That imprint of early trauma can change the way you think, feel, and act. People who have faced early adversity aren’t as flexible in their responses to life’s varied experiences. They have a higher number of bad days, and their bad days feel more stressful to them. When something good happens, they also feel more joyful.14 This pattern isn’t unhealthy in itself. It just leads to a more intense and dynamic emotional experience. However, that intensity makes it harder to ride out the transitions between emotions. People with a traumatic childhood background tend to have more difficulties in relationships. They’re more likely to engage in emotional eating and addictive behaviors.15 They’re not as good at taking care of themselves. These psychological reverberations of abuse may continue to shape mental and physical health all through life. In this way, early adversity may plant the seeds for a greater rate of telomere shortening, unless these resulting patterns of behavior are halted.

DON’T STEP ON MY PAW! THE EFFECTS OF MONSTROUS MOTHERING

Dr. Frankenstein, step aside. Today’s researchers know how to take perfectly nice rats and turn them into maternal monsters. In the lab, they can “build” a rat mother who mistreats her own pups. This is a hard subject for animal lovers to process, but it’s helpful reading for anyone who wants to understand the physiology of childhood adversity.

One of the more stressful circumstances for a lactating mama rat is a lack of adequate bedding. Rats don’t need luxurious mattresses to be comfortable, but mother lab rats do rely on things like facial tissues and strips of paper to build a little nest for their families. Another cause of high stress for rats is moving to a new place without enough time to habituate to it. By depriving mother rats of material for bedding and by moving them abruptly to a new cage, scientists can create highly stressed animals. Think of how stressful it would be to come home from the hospital with a newborn baby and then be greeted by a landlord who says, “Good, you’re finally here! Before you put the baby down, let me explain that we’ve moved you to a new house. Also, we took all your clothing and furniture to the dump. Bye!” You’ll have an inkling of what the mother rats were feeling.

These stressed mother rats mistreated their pups. They dropped them. They stepped on them. They spent less time nursing, licking, and grooming—supportive maternal activities that calm rat pups and lead to long-term changes in calming their neural stress responses. The poor pups cried out loudly, signaling their distress. This abusive early environment shaded the contours of the pups’ neural development. Compared to rats who were raised by nurturing mothers, these pups had longer telomeres in a part of their brains known as the amygdala, which governs the alarm response.18 The alarm response had apparently been switched on so often that the telomeres there were strong and robust. Not exactly a sign of a happy upbringing.

Having a strong connection between the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex, which can dampen that response, is critical for good emotion regulation. Sadly, the mistreated rat pups had shorter telomeres in a part of the prefrontal cortex. We already know that severe stress causes the nerve cells of the amygdala to branch out, to enlarge and connect to the nerve cells in other parts of the brain. The opposite tends to happen in the neurons of the prefrontal cortex, so that the connection between the two areas becomes weaker, and the rats can’t turn off the stress response as easily.19

LACK OF MOTHERING

Parental neglect is another condition that can harm telomeres. Steve Suomi of the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, has been studying parenting in rhesus monkeys for the past forty years. He has found that when they are raised in a nursery from birth, without their mother but socializing with peers, they show a range of problems. They are less playful, and more impulsive, aggressive, and stress reactive (and have lower levels of serotonin in their brains).20 He wanted to examine whether they have greater telomere attrition as well. He and his colleagues recently had the opportunity to study this in a small group of monkeys. They randomized some to be raised by their mothers and the others to be raised in a nursery for the first seven months of life. When their telomeres were measured four years later, the monkeys raised by their mothers had dramatically longer telomeres, around 2,000 base pairs longer, than the nursery-raised monkeys.21 While some of the shorter telomere length we see in disadvantaged children might have existed from birth, in this case the newborn monkeys were randomized at birth, so these differences were purely stemming from their early experiences. Fortunately, corrective experiences later in life, like being cared for by a grandparent, can reverse some of the problems of parentless monkeys.

NURTURING CHILDREN FOR HEALTHIER TELOMERES AND BETTER EMOTION REGULATION

It is depressing to read about the maltreatment of the rat pups, or motherless monkeys. But there is a bright side to the story: The rats who were raised by nurturing mothers had healthier telomeres. Same with the monkeys. Of course, nurturing parenting is essential for human babies and children, too. Nurturing parenting can help children develop good emotion regulation, meaning that they can experience negative feelings without getting overpowered by them.22 Think for a second, and you’ll surely have no problem producing examples of adults you know who struggle to regulate their emotions. These are the people who detonate at the slightest provocation. Road rage, anyone?

Maybe you know folks at the other extreme, who find their emotions so frightening that they’d rather end a friendship than work their way through a messy disagreement. They withdraw from anything that may stir up difficult feelings—careers, friendships, even the world outside their homes. Most of us hope that our children will learn more effective means of coping.

We can teach them. From early in life, children learn to regulate their emotions through nurturing care from their parents or caregivers. The baby cries; by showing concern, the parent acts as a kind of emotional copilot, guiding the child toward an understanding of his or her emotions. By soothing the baby and tending to its needs, the parent teaches the child that it’s possible to take care of feelings and to trust others. The child learns that distressing situations will eventually pass.

Fortunately for all of us who sometimes get angry in traffic or jump under the bedcovers when emotions run high, parents don’t have to have perfect emotion regulation to help their children. In the reassuring words of the great English pediatrician and researcher D. W. Winnicott, they just need to be “good enough.” They need to be caring, loving, and stable, with good psychological health, but they definitely don’t need to be perfect. Children raised in group homes and orphanages, however, don’t get anything close to good-enough parenting; they do not get the attention they need to develop normal emotional expression and regulation. They tend to have blunted emotional expression, an effect that can last throughout their lives.

The delicious act of snuggling with a baby, offering warmth, comfort, and care, has wondrous physiological effects on the child. Scientists believe that well-nurtured children learn to use their prefrontal cortex—the brain’s seat of judgment—as a brake on the amygdala and its fear response. Their cortisol levels are better regulated. Put these children on a blinking, whirling kiddie ride at the state fair, or tell them that they need to take an important test, and they’ll feel a healthy amount of excitement or worry. That’s what stress hormones are there for—to pump us up. When the ride comes to a stop, or when they put down their pencils, the cortisol begins its retreat. They’re not constantly swimming around in a flood of stress hormones.

Nurtured children also experience the delights of oxytocin, the hormone that’s released when you feel close to someone. Oxytocin is a stress-busting hormone; it reduces our blood pressure and imbues us with a glowing sense of wellbeing.23 (Women who breast-feed their children can experience the rush of oxytocin in an intense, palpable way.) Alas, the stress-buffering effect of having one’s parents nearby seems to wane once children reach adolescence.24

THE ABCS OF PARENTING VULNERABLE CHILDREN

In children who have begun their lives under traumatic circumstances, enhanced parenting techniques may help heal some of the telomere damage from early mistreatment. Mary Dozier, of the University of Delaware, has studied children who were exposed to adversity. Some lived in inadequate housing; some were neglected or witnessed or experienced domestic violence; some had parents who abused substances or who hurt each other. Dozier and her colleagues found that these children had shorter telomeres—except when their parents interacted with them in a very sensitive, responsive way.26 To give you a sense of what this kind of parenting looks like, here’s a very short assessment:

1. Your toddler bumps his head hard on a coffee table and looks at you as if ready to cry. What do you say?

“Oh, honey, are you okay? Do you need a hug?”

“Oh, honey, are you okay? Do you need a hug?”

“You’re okay. Hop up.”

“You’re okay. Hop up.”

“You shouldn’t be that close to the table. Move away from there.”

“You shouldn’t be that close to the table. Move away from there.”

You say nothing, hoping that he’ll move on to something else.

You say nothing, hoping that he’ll move on to something else.

2. Your child comes home from school and says that her best friend doesn’t want to be friends anymore. You say:

“I’m so sorry, honey. Do you want to talk about it?”

“I’m so sorry, honey. Do you want to talk about it?”

“You’ll have plenty of friends over time. Don’t worry.”

“You’ll have plenty of friends over time. Don’t worry.”

“What did you do that made her not want to be your friend?”

“What did you do that made her not want to be your friend?”

“Why don’t you get on your bike and go for a ride?”

“Why don’t you get on your bike and go for a ride?”

All of these answers can sound reasonable, and under individual circumstances, any of them might be. But there is only one correct response for a child who has been through trauma, and in both cases, that response is the first one. Under normal conditions, it may sometimes be appropriate to help a child learn to brush off a minor bump or scrape, for example. But children who’ve suffered from adversity are different. They may have a harder time regulating their emotions. They still need parents to be the emotional copilot—to reassure them that the parent has noticed their troubles and can be relied upon to help soothe them. They may need this reassurance over and over and over again. It takes time, but eventually children will learn how to respond to problems in a more adaptive way. And when they are older, they will be more likely to go to their parents with issues that they are worried about.

Dozier has developed a program known as Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-Up, or ABC, to teach this kind of exquisite responsiveness to parents of at-risk children. One group included American parents who were adopting international children. These weren’t people who lacked parenting skills. They were caring and committed. But the children they were adopting were statistically much more likely to have lived in group homes, to suffer from poor emotion regulation, to have telomere damage—the whole bushel of problems that come with childhood adversity. During this program, parents are coached to follow their child’s lead. For example, when a child starts to play a game by banging a spoon, a parent might be tempted to say, “Spoons are for stirring pudding” or “Let’s count the number of times you tap the bowl.” But these responses reflect the parent’s agenda, not the child’s. In Dozier’s program, the parent would be encouraged to join in the game, or to comment on what the child is doing: “You’re making a sound with your spoon and bowl!” These smooth interactions with the parent help at-risk children learn to regulate their emotions.

It’s a simple intervention, but the results are dramatic. Dozier also taught ABC to a group of parents who had been reported to Child Protective Services for allegedly neglecting their children. Before the course, the children’s cortisol levels had that blunted, broken response that characterizes burnout from overuse. After the parents had taken this short course, the children had a much more normal cortisol response. Their cortisol rose in the morning (a good, healthy sign that they were ready to take on the day), and declined throughout the day. This effect wasn’t just temporary. It lasted for years.27

TELOMERES AND STRESS-SENSITIVE CHILDREN

Was Rose a difficult baby? Her parents smile at the question. “Rose had colic for three years,” they say, laughing at their exaggeration as well as the kernel of truth that is behind it. Colic, in which babies cry incessantly for more than three hours a day, three days a week, generally begins at around two weeks of age and usually peaks at about six weeks. Rose was colicky, all right. As a newborn, she would nurse, nap briefly, have about five minutes of peaceful time… and then begin wailing again. Despite her name, Rose was no demure flower. Her parents, desperate to calm their crying baby, would take her for walks and strolls through the neighborhood—only to have older ladies rush up to them, exclaiming, “Something must be wrong with your child! Healthy babies do not cry this way!”

Nothing was wrong. Rose was clean, fed, warm, and cared for. She was just very, very sensitive. She was quick to cry and slow to settle down for sleep or quiet—thus her parents’ joke about her colic lasting for years. Small noises, like the running of the refrigerator motor, bothered her. When strangers held her, Rose would scream and try to wriggle out of their arms. As Rose got older, she wouldn’t wear clothes with tags; they felt too itchy. When the family signed up for a professional photography session, Rose hid her eyes from the bright lights. And any change in her daily routine was upsetting.

Was Rose sensitive because of the way her parents raised her? Were they too indulgent of her demands? Should they have taught her a lesson by insisting, say, that Rose wear whatever clothes they picked out for her, itchy or not? We can begin to answer these questions by talking about temperament. Temperament, the set of personality traits we’re born with, is like the deep cement foundation of a building. It can provide a stable undergirding, or it can make us tilt and shake in certain ways, especially during an “earthquake.” We can recognize our temperament and learn to deal with it, but we can’t really change our foundation. Temperament is biologically determined.

One aspect of temperament is stress sensitivity. Stress-sensitive children are more “permeable,” which means that for good or for ill, their environment doesn’t just bounce off them. It penetrates. These kids have bigger stress reactions to light, noise, and physical irritations. They are jolted by transitions, like going to back to school after the weekend (the “Monday effect”), or new situations, like staying at a grandparent’s house overnight. They have a stronger, magnified response to shifts in their environment, even small shifts that other children might not notice. Some of these children may react by acting angry or aggressive; others may internalize their feelings, coming across as quiet or sullen. Telomeres tend to be shorter in children who internalize their emotions.28 But when children have severe externalizing or acting-out disorders, such as attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity, and oppositional defiant disorder, their telomeres are shorter, too.29

Developmental pediatrician Tom Boyce has followed a group of kindergartners as they transition into their first year of school—a time that can be tough for stress-sensitive children. He and his colleagues hooked them up to sensors and then measured their physiological reactions to harmless but modestly stressful situations, like watching a scary video, having a few drops of lemon juice squirted onto their tongues, and (of course) performing one of those memory tasks. Most kids showed some signs of stress. But in a few kids, the stress responses were cranked up to their full force, both the hormonal responses and the autonomic nervous system. It was as if their bodies and brains thought the room was on fire. The bigger the stress responses, the shorter their telomeres tended to be.30

IS YOUR CHILD AN ORCHID?

It can all sound quite tragic. It may seem that people who are born with high-stress sensitivity have drawn the unlucky short straw—or, in this case, the short telomere. Actually, Boyce and others have found that certain environments allow stress-sensitive people to thrive, sometimes even more than their less sensitive peers.

In many studies Boyce has found that children who are especially stress sensitive do poorly when they are in large, crowded, chaotic classrooms or harsh family environments, but when they are in classrooms or families with warm, nurturing adults, they actually do better than the average child. They are less sick with colds and flu; they show fewer symptoms of depression or anxiety; they are even injured less often than other children.31

Boyce calls these stress-sensitive children “orchids.” Without exquisite care and attention, an orchid won’t bloom. Put it in the optimal conditions of a greenhouse, though, and it produces flowers of surpassing beauty. Around 20 percent of children have an orchid-like temperament. Again, it’s not something that parents create. Those orchid seeds are planted long before birth.

A way to understand these “seeds” is to analyze the genetic signatures of orchid children. Children (and adults) with more variations in the genes for neurotransmitters that regulate mood, like dopamine and serotonin, tend to be more sensitive to stress. They’re orchids. Those most stress sensitive, based on genetics, tend to benefit more from supportive interventions and will thrive.32 To test whether this genetic signature affects how children’s telomeres respond to adversity, a small and preliminary study looked at forty boys. Half were from stable homes; the other half were from harsh social environments characterized by poverty, unresponsive parenting, and family structures that kept changing. The boys exposed to harsh environments had shorter telomeres—but especially if they had the more stress-sensitive genes. That’s the obvious disadvantage of being permeable to the environment—a rough situation is going to do deep damage. Then the boys revealed the flip side, the beauty of permeability: When they lived in stable environments, their telomeres weren’t just okay. They were longer, healthier, than the telomeres of the boys without the genetic variations. This early study suggests that being sensitive and permeable may be a benefit when in a supportive environment.33

This is a fascinating story in personality research, and one of the hottest topics in the stress field. Sensitivity is neither a good nor a bad trait. It’s just one of the cards we’re dealt. It’s best if we can clearly identify the card so that we can know how to play our hand. Orchid children benefit from warmth, gentle correction, and a consistent routine. They need assistance and patience as they make transitions to a new situation. As high-stress reactors, orchid children can benefit from learning the challenge response—and you can also teach them techniques like thought awareness and mindful breathing, which help them put some calming distance between themselves (their thoughts) and their active stress responses.

PARENTING TEENS FOR TELOMERE HEALTH

Parent: Look at what I found underneath that mess on your desk today. Am I correct in thinking that this is an assignment for a history paper?

Teen: I don’t know.

Parent: It’s due tomorrow. Have you even started it yet?

Teen: I don’t know.

Parent: Answer me respectfully! Let’s try again: Is this or is this not an assignment for a history paper that is due tomorrow?

Teen: I don’t have to listen to this! You’re just jealous because you never had fun when you were my age. You didn’t know how!

Parent: You just bought yourself a grounding. You’ll be staying home this Friday night.

Teen [shouting]: Go to hell!

Parent [also shouting]: AND all day Saturday!

So far we’ve talked about children, mostly younger ones. But what about teenagers? Parent-teen conflicts like the one above, in which an issue (like homework) is raised, fought over, but left unresolved, are common. These open-ended conflicts leave the teen with a lot of anger—and psychologists know what anger does to that cauldron of physiological responses known as stress soup. Anger heats that soup up to a rolling boil. And anger can have telomere-shortening effects, but fortunately this can be turned around through a shift in parenting style.

Gene Brody, a researcher of family studies at the University of Georgia, gives us insight into the role of parental support during the teen years, and how to bolster it. Brody tracked a group of African American teens in the impoverished rural south of the United States. It’s an area where young adults leave high school only to find that there are few jobs of any kind, let alone satisfying jobs, and few resources to help them make the transition to adult life. Alcohol use in particular is high. Brody recruited a group of these teens for his Adults in the Making program, in which teens are given emotional support and job advice. The instructors also provide strategies for handling racism. The teens’ parents are included in the program, too—they’re taught to tell their child in clear, vigorous terms to stay away from drugs and alcohol, for example. They have six classes where parents and teens learn skills in separate groups and then practice them together at the end. Half the teens did not get the classes. Five years later, Brody measured their telomeres. First of all, having unsupportive parenting—lots of arguments and little emotional support—was associated with shorter telomere length and more substance use five years later. However, among this vulnerable group, the teens that had received the supportive intervention had longer telomeres compared to teens who hadn’t. This effect is partly explained by the teens feeling less angry.34

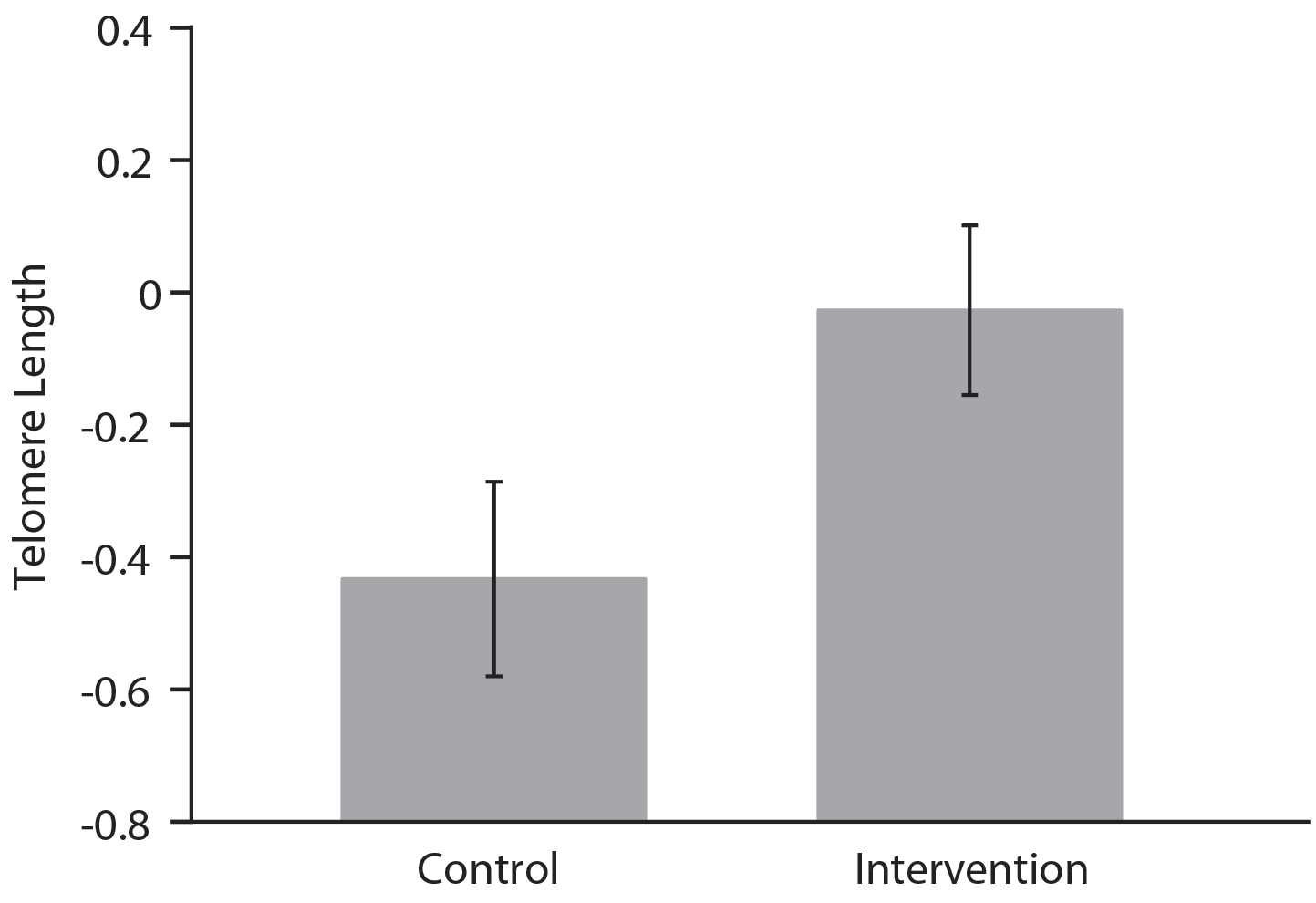

Figure 28: Family Resilience Classes and Telomeres. Among the teenagers whose parents showed very unsupportive parenting, those who were in the supportive intervention group had significantly longer telomeres five years later. (This is after adjusting for factors such as social status, stressful events, smoking, alcohol use, and body mass index.)35

Brody’s study looked at teens in a very particular setting and at a certain income level. But his findings provide food for thought for all of us. No matter where they live, and no matter how rich or poor, all children’s brains and bodies are undergoing tremendous changes during adolescence. It’s common for teens to follow a jagged path for a while, especially because the teen brain experiences risk differently. They tend to react to threat as a thrill; when they take risks, they feel good.36 The same behaviors are, naturally, terrifying to the more seasoned adults in their lives. Cue the parental worries, dead-of-night ruminations, and fears that explode into fights between parent and teen. A few conflicts are probably unavoidable. But when conflicts are constant, or when the tension becomes so toxic that it pollutes the air of the household, teens can become angry and rebellious. Or depressed and anxious, if they’re the type to drive their feelings underground. The Renewal Lab at the end of this chapter offers a few suggestions for staying attuned to teens when they are in a difficult, hyperreactive mode.

We have been talking about how to help children heal the telomere damage caused by adversity. Early intervention, support, and emotional attunement can provide buffers for at-risk children. But you may have had prolonged, severe stress in early life yourself. If you grew up in a dangerous neighborhood, in an abusive home, or if your family had to struggle just to get food and shelter, your telomeres may have experienced some damage. Use this knowledge as motivation to take care of your telomeres now. Recognize old patterns, such as turning to food for comfort. You have more control over what happens to you now that you are an adult. And now you know how to protect the base pairs of telomeres you have left. You may especially want to take advantage of techniques that help soothe the stress response. By becoming less stress reactive, you will protect your telomeres—and there is a bonus. You will also be calmer and stronger for the children (and other loved ones) who are in your life.

TELOMERE TIPS

Severe childhood trauma is linked to shorter telomeres. Trauma can also reverberate into adulthood in the form of poor health behaviors and relationship difficulties, which may continue to shorten telomeres. If you suffered severe childhood adversity, you can take steps now to buffer its effects on your wellbeing and telomeres.

Severe childhood trauma is linked to shorter telomeres. Trauma can also reverberate into adulthood in the form of poor health behaviors and relationship difficulties, which may continue to shorten telomeres. If you suffered severe childhood adversity, you can take steps now to buffer its effects on your wellbeing and telomeres.

Although severe childhood adversity can be damaging, moderate childhood stress may actually be healthy, provided that the child has enough support during the stressful time.

Although severe childhood adversity can be damaging, moderate childhood stress may actually be healthy, provided that the child has enough support during the stressful time.

Parents can support their young children’s telomeres by practicing warm, nurturing attunement. This responsiveness is especially important for children who have already experienced trauma or who are born with the sensitive “orchid” temperament.

Parents can support their young children’s telomeres by practicing warm, nurturing attunement. This responsiveness is especially important for children who have already experienced trauma or who are born with the sensitive “orchid” temperament.