A LEISTER CROWLEY was born on October 12, 1875, as Edward Alexander Crowley. He was named after his father, Edward Crowley (1834–1887), who had been named after his father before him (ca. 1796–1856). Although Edward the Third would change his name to Aleister (a Gaelic form of his middle name, Alexander) upon entering the University of Cambridge, the forces that shaped Aleister Crowley into the magician, prophet, and rebel To Mega Therion were very much in place from birth.

In his Confessions , Crowley made several dubious claims for predestined greatness: He was of noble descent (from “the Breton family of de Quérouaille—which gave England a Duchess of Portsmouth” 1 ). He was born with the characteristic marks of a Buddha (having four hairs on his chest in the form of a swastika, and being tongue-tied, requiring childhood surgery to cut the frænum under his tongue to allow him to speak). And his birthplace of Leamington was in the same county (Warwicksire) as England's other great poet, William Shakespeare.

The Crowleys were a Quaker family from Alton that had run a brewery near Croydon, Surrey, for over two hundred years. In 1821, Aleister's great-uncle, Abraham Crowley (ca. 1796–1864), and his sons Charles Sedgefield and Henry, purchased the Brewhouse in Turk Street from James Baverstock, who had introduced scientific instrumentation into brewing. A.C.S. & H. Crowley— later Crowley & Co.—was hugely successful in offering beer and a sandwich for four pence at its Alton Alehouses, essentially inventing the pub lunch. The success of the business left an impression in the literature of the era: In Edmund Yates: His Recollections and Experiences (1884), Yates recounts lunching at “Crowley's Alton Alehouse,” whose shops were “exceedingly popular with young men who did not particularly care about hanging round the bars or taverns” (vol. 1, p. 121). In Praise of Ale (1888) describes how the firm “L. and S.W.R. transports ‘Alton Ale’ in large quantities to London” (p. 462). Even Charles Dickens, in the November 11, 1854, edition of his weekly journal Household Words , remarked that Alton's growth boom included “a feeding place, ‘established to supply the Railway public with a first-rate sandwich and a sparkling glass of Crowley's Ale. . .’” (p. 291).

A label from one of Crowley's Alton Ales

The Crowley family also prospered through involvement in the British rail by the brothers Charles Sedgefield and Edward. Charles Sedgefield was director of several railways—including the London and Croydon Railway and the Sudbury and Halstead Railway— and deputy chairman of the Direct London and Portsmouth Railway Company. Aleister's grandfather Edward similarly directed the London, Brighton, and South Coast Railway, plus the Direct London and Portsmouth Railway Company and the Brighton and Chichester Railway. 2 In November, 1852—following a tragic collision in Red Hill on the Brighton Line managed by his father— Jonathan Sparrow Crowley invented “Crowley's Safety Switch and Self-Acting Railway Signals” to prevent such tragedies in the future. 3 Aleister Crowley alluded to this family history when he quipped, “My father would refuse to buy railway shares because railways were not mentioned in the Bible!” 4

On March 24, 1877—seven months before Aleister's second birthday—the Crowleys sold their brewery to Abraham Crowley's son-in-law, Joseph Burrell. Edward Crowley II shrewdly reinvested his money into Amsterdam's waterworks. While the investment details are unknown, English businessmen around this time founded the highly successful Amsterdam Water Works Company in 1865, whose 1872 expansion drew thousands of workers to the company. It is likely that Edward Crowley invested money into this very business. According to A.C., his father quipped sardonically that “he had been an abstainer for nineteen years, during which he had shares in a brewery. He had now ceased to abstain for some time, but all his money was invested in a waterworks.” 5 The family's prosperity is demonstrated by the fact that, in their household in Warwickshire, the servants outnumbered family members.

Edward Crowley broke from his family's Quaker roots, embracing a fledgling fundamentalist faith known as the Brethren (or Plymouth Brethren). The faith was based on Matthew 18:20 (“Where two or three are gathered together in my name, there am I in the midst of them”), arguing radically that believers require no priests or ministers to celebrate the Lord's Supper. The faith interpreted the Bible literally, with the precise date of creation ascertainable to roughly 4000 B.C.E. Christ's return was also believed to be imminent, and some even regarded financial investments and savings as evidence of lack of faith. Edward Crowley was an active and prolific spokesperson for the Brethren faith. Naylor (2004) lists over one hundred different tracts that Edward Crowley printed for distribution both by mail and on his walking tours around England. He was important enough to earn a mention in The History of the Brethren 1826–1936 .

The Brethren faith was indeed Spartan: They did not celebrate traditional Christian holidays, believing them (rightly) to be based on older pagan festivals. Childhood reading was strictly monitored and restricted to approved books, of which the Bible was most encouraged for continual study. Young Aleister was only allowed to play with other Brethren children. And when he misbehaved, his mother said he was the Beast from Revelation—a moniker that would, in later years, wind up sticking. Nevertheless, Crowley reports a happy early childhood during which he clearly idolized his charismatic and deeply religious father.

Events in his early teen years, however, embittered him against religion. It began with the frequent schisms (or “divisions”) that plagued the Brethren. Young Crowley couldn't grasp how one day dear family friends were numbered among the chosen and righteous ones to enter God's kingdom, and then the next day were condemned sinners with whom he was forbidden contact. When his preaching father developed tongue cancer, the irony could not have been lost on young Crowley. Upon the advice of the church, Edward Crowley shunned conventional medicine in favor of homeopathic treatment, moving the family homestead to Southampton in order to be closer to his doctor. He died within a year. Aleister was some six months shy of his twelfth birthday.

So beloved was the memory of his father that Crowley would not tolerate anyone's encroachment on his domain. When his mother took up Edward Crowley's mailing list and continued to send out Brethren literature, A.C. characterized her as “a brainless bigot of the most narrow, illogical and inhuman type.” 6 And when they moved in with his uncle, Tom Bond Bishop, himself a lay preacher and philanthropist, Crowley regarded his faith as “extraordinarily narrow, ignorant and bigoted Evangelicalism.” 7 He resented his uncle so much that he dedicated his parody of fundamentalism, “Elder Eel,” to him.

The exclusive schools he attended meted out injustice from bullies and staff alike. When students became ill after a wellintentioned program to feed the homeless, it was considered God's punishment for some undisclosed sin. Crowley became rebellious after his father's death, which his masters, at first, attributed to grief. But when Crowley was anonymously accused of an unspecified immorality, he was isolated from his fellow students outside class time and fed only bread and water until he confessed. He had no idea what he supposedly did, and came down with a lifethreatening kidney disease (albuminuria) before his mother and uncle un-enrolled him, and sent him for a cure of country air and exercise with a private tutor. Fortunately, his tutor was more liberal, and demonstrated to the recovering Crowley that one could be a good person yet still enjoy tobacco, alcohol, and sex. “He taught me sense and manhood,” Crowley recalled, “and I shall not easily forget my debt to him.” 8

Although embittered by his experience of the Brethren faith, Crowley did not reject religion outright. “I did not hate God or Christ, but merely the God and Christ of the people whom I hated.” 9 In his early college years, an existential crisis led him to the realization that all ambitions and careers are ultimately lost in the sands of time. He concluded the only thing that mattered, that endured, was the spirit. His quest for spiritual truth led him to mysticism and occultism and the search for the Great White Lodge, an invisible college of enlightened teachers offering guidance to those determined enough to find its door. So the stage was set for this sheltered, spiritual, wealthy, handsome, and profoundly rebellious young man to become Aleister Crowley.

Entering Cambridge's Trinity College in the fall of 1895 in moral sciences, he enjoyed his majority and independence like any other college student: with experimentation. He voraciously read the books once forbidden to him and quickly amassed a large library of poetry, religion, history, philosophy, and science. Inspired by the likes of Shelley, Keats, Browning, and Swinburne, he began to write his own poetry, alternately florid, sensuous, and sarcastic. He moved in Aesthetic or Decadent circles, befriending Oscar Wilde's publisher Leonard Smithers, who helped him to selfpublish his poetry. He experimented with sex, complaining famously of “the stupidity of having had to waste uncounted priceless hours in chasing what ought to have been brought to the back door every evening with the milk!” 10 ; he even lived for a time as the “wife” of the Cambridge transvestite performer Herbert Charles Jerome Pollitt (a.k.a. Diane de Rougy [1871–1942]). At this time, he also dropped the names “Alick” and “Alec” of his boyhood, adopting instead a Gaelic form, Aleister.

Although he competed in the Cambridge chess club and Magpie and Stump Debating Society, he was more of a loner at heart. He did not attend chapel, which was mandatory for students (he claimed it was against the faith in which he was raised). Nor did he take meals with his classmates, paying the kitchen staff to bring meals to his room at times that better suited him. And he often missed classes, with one professor even permitting the precocious scholar to skip lectures and study independently. After three years of college, he, “like Byron, Shelley, Swinburne and Tennyson,” 11 left without graduating.

In his lifetime, Aleister Crowley published scores of books, pamphlets, broadsheets, and articles, a vast portion of them being poetic works. His poetry has always garnered mixed reviews. The Athenæum , for instance, disliked his poetry's sensuality. 12 Others, most notably G.K. Chesterton (1874–1936), derided its subject matter. W.B. Yeats notably said that Crowley “has written about six lines, amid much bad rhetoric, of real poetry.” 13 For all his critics, however, Crowley also has his fans. Significantly, English Review editor Austin Harrison called Crowley the greatest metrical poet since Swinburne. J.F.C. Fuller, fifty years after parting ways with Crowley, still regarded him as “one of England's greatest lyric poets, and among those of France, comparable with Rimbaud and Baudelaire,” and certain of his works as “of the highest poetic genius.” 14 Perhaps the highest tribute possible is his inclusion in The Cambridge Poets 1900–1913 (1913) and The Oxford Book of English Mystical Verse (1916). As Amphlett Micklewright wrote in his appreciation of Crowley,

It is not always the case that the poems of occultists are essential to an understanding of their work. But Aleister Crowley is fundamentally an artist. He is a creative personality, expressing his individuality in terms of rhythm. His sense of the rhythmic, which ultimately implies the sense of a fundamental beauty, is aptly expressed whether in prose or in verse; his art is a necessary entrance to an understanding of his occultism. 15

During his recovery from albuminuria, Crowley discovered a love— and talent—for mountain climbing; indeed, he set records around the world and helped to introduce innovations into the sport. While vacationing in the Swiss Alps in 1898, he stopped in a beer hall and wound up giving an impromptu lecture on alchemy. He was mortified when, afterwards, one of the drinkers introduced himself as Julian L. Baker, an analytical chemist and alchemist. He promised to introduce Crowley to an invisible college once they returned to London.

That invisible college wound up being the Order of the Golden Dawn (G.D.), the most celebrated and influential late nineteenthcentury magical society. Founded in 1888 as an outgrowth of the Societas Rosicruciana in Anglia (S.R.I.A.), it disseminated occult teachings without the S.R.I.A.'s requirements of belief in the Christian Trinity, being a Master Mason, and being male. Its founding members—William Wynn Westcott (1848–1925), William Robert Woodman (1828–1891), and Samuel Liddell MacGregor Mathers (1854–1918)—were all accomplished in esoteric freemasonry, Rosicrucianism, and occult studies. Much of the group's ritual and study material drew on their published and unpublished writings. The group began to founder after Woodman died in 1891. Westcott succeeded Woodman as head of the S.R.I.A., unofficially leaving stewardship of the Golden Dawn to Mathers, whose recent move to Paris would later leave London members weary of answering to an absentee hierophant.

Crowley joined the G.D. in November 1898. He mastered all the material—even gaining a private tutor in Allan Bennett, the Order's most respected magician—and advanced steadily through the five “Outer Order” grades. Ironically, Crowley's friendship with the G.D.'s leader Mathers hindered his advancement into the higher degrees, as the senior London members united almost unanimously in opposition to Crowley's further advancement. Just as he hit this glass ceiling, Mathers issued an ultimatum to the London lodge: either sign an oath of obedience to him or face expulsion. A predictable schism ensued. Disappointed that the order didn't live up to the lofty ideal of the Great White Lodge, Crowley drifted away from the G.D. and concluded that Mathers was no longer in contact with the Secret Chiefs who ran the invisible college. Mathers would ultimately expel Crowley some years later.

For much of the next four years, he traveled the world. He set mountaineering records in Mexico and the Himalayas. He went big game hunting in India and Sri Lanka. He lived in Sri Lanka with Allan Bennett, studying yoga, Hinduism, and Buddhism. He was part of the circle of artists, poets, and writers at Le Chat Blanc in Paris, where he mixed with W. Somerset Maugham, Rodin, and, most importantly, his future brother-in-law, portrait painter Gerald Kelly. 16

Crowley first met Gerald Kelly when both were Cambridge undergraduates. Through him, in 1903, he also met Gerald's sister, Rose. She confided in Crowley an unhappy circumstance. Under pressure from her family, she was awaiting the arrival of a suitor from America, but was actually in love with a married man with whom she was having an affair. Crowley chivalrously offered to get her off the hook by marrying her and letting her conduct her affairs with whomever she pleased. Rose agreed, and they slipped away and eloped early the next morning, much to the family's surprise and dismay.

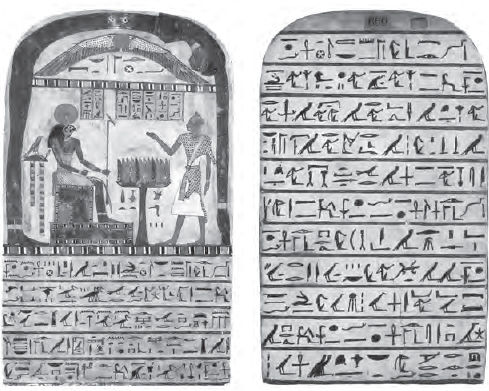

The Stele of Revealing, obverse The Stele of Revealing, reverse

To their own surprise, the newlyweds found themselves in love. Crowley took Rose on a honeymoon to Egypt, where he showed her the pyramids and demonstrated some magick in the King's Chamber. She responded by later going into a dreamy state and speaking distractedly about how the Egyptian god Horus wanted a word with Crowley. Although he didn't take it seriously at first, he ultimately quizzed Rose—or whoever was speaking through her— about Horus. Remarkably, Rose, who knew nothing at all about Egyptian mythology, answered every question perfectly. As a final test, Crowley took her to a museum and asked her to point out an image of Horus. Walking past several other images of the god, Rose pointed to a wooden stele across the room. Not only did the stele show a picture of Horus, but it bore museum catalog number 666. It was all the proof he needed.

Rose described a ceremony (later called the Supreme Ritual) for Crowley to perform on March 20, 1904, the vernal equinox. He was subsequently instructed to go into his Cairo flat at precisely noon on April 8, 9, and 10 and, for the next hour, write down the words he heard. This he did, and the result is The Book of the Law . 17 It is a text that exhilarated, bewildered, and even shocked him. It not only declares the beginning of a new era for humanity, but names Crowley its prophet as the Beast 666. 18 It spells out a doctrine of joy, empowerment, and individual liberty, and calls on all people to discover and fulfill their true nature. Its central tenet is “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law.” Crowley would ultimately devote his life to spreading its word.

At first, however, he didn't know what to make of The Book of the Law. He sent typescripts to some colleagues who were just as nonplussed as he was. So he set it aside and returned to his other pursuits.

When Aleister Crowley set out in 1905 to be the first person to climb Kangchenjunga—the third highest mountain in the world— he'd already amassed impressive credentials in the sport, which he took up at age 17. According to mountaineering writer Colin Wells:

Even without his diabolical extracurricular activities, Crowley's climbing legacy ensures him a place in mountaineering's Hall of Fame. For a time, he held claim to the world altitude record and the hardest free moves done on rock. Though his stint on the heights was comparatively short-lived ... he was part of the leading pack of early rock climbers who created a recognizably modern style of technical climbing in the English Lake District. He was also the first to dare climb the uniquely insecure chalk cliffs of England's south coast.

In mountaineering, he was the first to seriously attempt K2 and Kangchenjunga, and pioneered guideless climbing in the Alps. 19

He'd previously (1902) been on the team that tackled K2, the secondhighest mountain in the world. The only thing keeping him from the world's highest peak, Mt. Everest, was that Europeans were not allowed access at the time. The Kangchenjunga climb was Crowley's first time leading an expedition, and his style—mixing authoritarianism with daring that often bordered on folly—did not sit well with his team. They quarreled over what was the best ascent up the mountain (history ultimately proved Crowley to be correct). At one point part of his team mutinied and left the expedition; during their descent, Swiss climber Alexis Pache and several porters were killed in an avalanche. Crowley's failure to help with the rescue effort ruined his reputation as a climber. 20 Between these deaths and his failure to reach the peak, Crowley would never climb again.

A

A

Crowley took Rose and their infant daughter along on other adventures in 1906, including a trek across southern China. During this time, he began daily recitations of the Augoeides invocation,

21

which he thought would eventually unite him with his Holy Guardian Angel—the quintessential goal of magick. He experienced several revelations during this trip, including attaining the grade of Exempt Adept 7°= 4 and realizing that the gods had a plan

for him.

22

Taking a separate route home from his family, Crowley arrived in England to find news that his infant daughter had died of typhoid, and that Rose had sunken into alcoholism. With his personal life in ruin, he sought understanding through magick, and concluded that the gods were punishing him for shirking his duties as their chosen prophet.

and realizing that the gods had a plan

for him.

22

Taking a separate route home from his family, Crowley arrived in England to find news that his infant daughter had died of typhoid, and that Rose had sunken into alcoholism. With his personal life in ruin, he sought understanding through magick, and concluded that the gods were punishing him for shirking his duties as their chosen prophet.

Crowley became ill and went to stay with his friend and G.D. mentor, George Cecil Jones (Frater D.D.S.). He describes what happened next in “Liber LXI vel Causae” (the history lection):

19. Returning to England, he laid his achievements humbly at the feet of a certain adept D.D.S., who welcomed him brotherly and admitted his title to the grade which he had so hardly won.

20. Thereupon these two adepts conferred together, saying: May it not be written that the tribulations shall be shortened? Wherefore they resolved to establish a new Order which should be free from the errors and deceits of the former one.

21. Without Authority they could not do this, exalted as their rank was among adepts. They resolved to prepare all things, great and small, against that day when such Authority should be received by them, since they knew not where to seek for higher adepts than themselves, but knew that the true way to attract the notice of such was to equilibrate the symbols. The temple must be builded before the God can indwell it.

They were joined by Captain (later Major-General) J.F.C. Fuller (Frater N.S.F. [1878–1966]). 23 Fuller had entered the contest for the “best essay on the works of Aleister Crowley,” which Crowley had sponsored to promote his three-volume Collected Works ; being the only entrant, Fuller won. He had studied yoga while stationed abroad, and had a keen interest in all things occult. To quote “Liber Causae” again:

27. In the fullness of time, even as a blossoming tree that beareth fruit in its season, all these pains were ended, and these adepts and their companions obtained the reward which they had sought—they were to be admitted to the Eternal and Invisible Order that hath no name among men.

Crowley immediately launched an ambitious publication schedule of the official organ of A A

A , The Equinox

, which appeared at six-month intervals for five years, between 1909 and 1913.

, The Equinox

, which appeared at six-month intervals for five years, between 1909 and 1913.

Membership thrived during the first years of The Equinox

's publication, spurred in part by publicity from Mathers' failed injunction to prevent Crowley from publishing the Golden Dawn's rituals. The press proved to be a double-edged sword, however, when it panned The Rites of Eleusis

. This daring performance series (one for each of the seven planets) blended sacred poetry, music, and dance, and was presented on consecutive Wednesdays at London's Caxton Hall in October and November 1910. The yellow press seized the opportunity to dredge up whatever dirt they could on Crowley: from his divorce from Rose to his rumored homosexuality, all was fair game. Where the facts were insufficient, rumor, gossip, and fiction ruled the day. The negative press about Crowley, his friends, and their cult of immorality—coupled with Crowley's reluctance to defend himself and his circle—drove away many members, including A A

A charter members J.F.C. Fuller and George Cecil Jones,

24

leaving behind but a dedicated core.

charter members J.F.C. Fuller and George Cecil Jones,

24

leaving behind but a dedicated core.

The Book of Lies (1912) was an exercise in writing 93 brief and unrelated chapters of magical instruction whose contents were dictated by their chapter number. “I wrote one or more daily at lunch or dinner by the aid of the god Dionysus,” Crowley recalled coyly in his Confessions . 25 Yet one of these chapters raised the ire of Theodor Reuss, head of Ordo Templi Orientis, as it revealed in plain language the Order's central secret. When Reuss came calling, Crowley claimed ignorance and blamed it on the wine. However, once he realized what the secret was, it changed his life forever. Arguably, the only event more profound for him in his life was receiving The Book of the Law . Reuss appointed Crowley the British head of the Oriental Templars, with the title “Supreme and Holy King of Ireland, Iona, and all the Britains.” For this role, Crowley chose the magical name Baphomet—after the goat-headed god for which the Templars were burnt as heretics for worshipping. 26

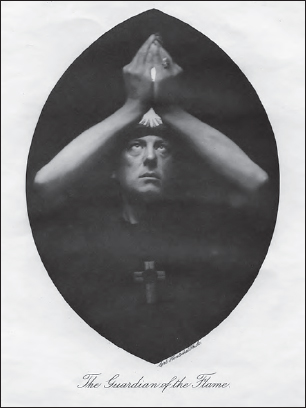

Photo of Crowley from the Rites of Eleusis

publicity booklet (1910)

Crowley energized the O.T.O. in a way that Reuss seemed unable to do. He revised the English rituals to conform with The Book of the Law and soon began performing O.T.O. initiations. Crowley succeeded Reuss as Outer Head of the Order on Reuss's death in 1923.

When World War I broke out in England in 1914, Crowley moved to America. This he did for several reasons. First, he had spent his inheritance on self-publishing, travel, mountaineering, and other luxuries, and hoped desperately that New York lawyer and patron of the arts John Quinn (1870–1924) would be interested in purchasing one-of-a-kind editions of Crowley's works. (Quinn would buy only a few of Crowley's books.) Second, he had offered his services to the British military but had been turned down. Crowley believed that he could help his country by infiltrating the German propaganda machine in the U.S., discrediting them, and helping to bring America into the war on England's side. This scheme required him to behave like a traitor, posing as an Irish nationalist, publicly burning his British passport, and writing over-the-top anti-British propaganda. Many dismissed Crowley's claim to being an agent as nothing more than disingenuous backpedaling after he realized he'd backed the wrong horse. However, considerable evidence suggests that he indeed acted with the knowledge of authorities in both America and England, and this is confirmed in U.S. military intelligence files. When, on February 2, 1917, the U.S. broke off diplomatic ties with Germany (as a prelude to declaring war), Crowley wrote in his diary, “My 2¼ years' work crowned with success.” 27

While in the U.S., Crowley seized the opportunity to sell more books, begin publishing a new edition of The Equinox , and try to establish an O.T.O. body. While he wasn't very successful in any of these endeavors, he underwent a months-long process of initiation from which he emerged as the Magus To Mega Therion (the Great Beast), his seat as a Master of the Temple filled by his Magical Son and heir apparent, Charles Stansfeld Jones (1886–1950), better known by his occult nom de plume, Frater Achad. Jones was a brilliant and gifted student who helped Crowley to decipher some of the more cryptic passages of The Book of the Law , and who served as his “field organizer” for a fledgling O.T.O. group in Detroit. Although they later fell out, Jones continued to take on students and reference Crowley extensively in his own books QBL or the Bride's Reception (1922), The Egyptian Revival (1923), The Chalice of Ecstasy (1923), Crystal Vision through Crystal Gazing (1923), and The Anatomy of the Body of God (1925).

When hostilities ended in Europe, Crowley and his then-Scarlet Woman,

28

New York school teacher Leah Hirsig (1883–1975), made their way to Cefalù, Sicily, to establish a Thelemic commune. He dubbed it the Abbey of Thelema after the Gargantua

and Pantagruel

of François Rabelais (ca. 1495–1553). Life there was devoted to magick, with a daily routine of ritual and study for all who cared to visit—and an assorted group of bohemians, eccentrics, and occultists did indeed visit. Some—like the American character actress Jane Wolfe (1875–1958)

29

and Australian O.T.O. Viceroy (organizer) Frank Bennett (1868–1930)—were so profoundly changed by the visit that they spent the rest of their lives representing Crowley, Thelema, the A A

A , and O.T.O. Others, like writer Mary Butts (1890–1937) and her lover Cecil Maitland (1892–1926), returned to London “looking like ghosts.”

30

The most tragic tale, however, belongs to Oxford student Frederick Charles

“Raoul” Loveday (1900–1923): a bright and promising disciple who quickly became very dear to Crowley, he died after drinking contaminated spring water while staying at the Abbey. Loveday's grief-stricken and embittered widow Betty May (b. 1893) returned to London and sold the tabloids an outrageous tale of how Raoul died from drinking the blood of a cat sacrificed during an infernal ritual. The London press unleashed the full force of its pen upon Crowley, branding him with his now-infamous title of “The Wickedest Man in the World.” Crowley lacked the funds to return to London and defend himself, so he frustratedly watched the press clippings mount until the government finally asked him to leave Italy.

31

, and O.T.O. Others, like writer Mary Butts (1890–1937) and her lover Cecil Maitland (1892–1926), returned to London “looking like ghosts.”

30

The most tragic tale, however, belongs to Oxford student Frederick Charles

“Raoul” Loveday (1900–1923): a bright and promising disciple who quickly became very dear to Crowley, he died after drinking contaminated spring water while staying at the Abbey. Loveday's grief-stricken and embittered widow Betty May (b. 1893) returned to London and sold the tabloids an outrageous tale of how Raoul died from drinking the blood of a cat sacrificed during an infernal ritual. The London press unleashed the full force of its pen upon Crowley, branding him with his now-infamous title of “The Wickedest Man in the World.” Crowley lacked the funds to return to London and defend himself, so he frustratedly watched the press clippings mount until the government finally asked him to leave Italy.

31

While living at the Abbey, Crowley contributed several articles to The English Review under various pseudonyms. Two of these, “The Great Drug Delusion” and “The Drug Panic,” described Crowley's attitudes on drug legalization and his emerging theory of addiction. Crowley had experimented with the magical use of drugs, most of which he acquired legally from his chemist. He also experimented with the mescal cactus and its psychoactive effects while climbing mountains in Mexico in 1900. England's passage of the Dangerous Drugs Act in 1920, however, changed things for the worse for him. He had developed severe asthma as a result of his high-altitude climbs. In 1919, his physician prescribed heroin as an analgesic and antispasmodic. With the Dangerous Drugs Act, Crowley was one of many people who were physically dependent on a medicine they could no longer purchase legally. His efforts to wean himself 32 prompted a great deal of self-reflection, from which emerged his theory of addiction. Recreational drug use, lacking purpose, is ultimately hedonistic and leads to dependence; but use directed toward the accomplishment of one's True Will, by virtue of keeping a higher purpose ever in mind, protects one from addiction.

Crowley pitched a novel based on these principles to book publisher William Collins, who contracted the title. Amazingly, he dictated the entirety of The Diary of a Drug Fiend in twenty-eight days. It tells the story of the protagonist's life in England's drug underground, his meeting the wise and enigmatic King Lamus (Crowley), and his redemption and recovery at the Abbey of Thelema. Not only was it a novel, it was an advertisement for the Abbey as a drug rehabilitation clinic. The release of this controversially-titled book was greeted by the press with the outcry that was now customary for Crowley: The Sunday Express called it “A Book for Burning.” 33 Collins quietly let the first edition sell out without printing any further copies.

Following Crowley's 1923 expulsion from Italy, the Abbey of Thelema eventually closed as its residents gradually drifted away. Crowley wandered around the region, including Tunisia, Germany, and France. Settling for a time in Paris with his new secretary, Francis Israel Regardie (1907–1985), and a new student, Gerald Yorke (1901–1983), he set his sights on publishing his magnum opus, Magick in Theory and Practice (1929–1930). It was part three of a four-part series he called Book Four or Liber ABA . The first two parts he had written in 1911 and 1912 under orders from an entity called Ab-ul-diz, whom he and Mary Desti (a.k.a. Mary d'Este Sturges [1871–1931]) had contacted during a magical working in Switzerland. As with much of Crowley's work, this third part had been around in outline and draft form for years. It was the basis for a series of classes on magick that he taught in the U.S., and Mary Butts helped Crowley with it while staying at the Abbey of Thelema. The book garnered positive reviews; even his former student Victor Neuburg gave it a glowing recommendation in the Sunday Referee .

The rare dust wrapper to

The Diary of a Drug Fiend (1922).

Picture credit: Anthony W. Iannotti.

Encouraged by this new success, Crowley returned to England. He was soon signed by P.R. Stephensen to the Mandrake Press, which launched a campaign to rehabilitate his reputation and promote a series of new titles. These included a short-story collection, The Stratagem and Other Stories (1929), his novel Moonchild (1929), and the first two volumes of his six-volume Confessions (1929). Stephensen also defended Mandrake's new author in The Legend of Aleister Crowley (1930), an exposure of Crowley's mistreatment in the press and a defense of his body of work.

Spurred on by Mandrake's efforts, Crowley successfully sued a London bookseller for libel for advertising a copy of The Diary of a Drug Fiend as “withdrawn from circulation.” This encouraged him to attempt other lawsuits against acquaintances whose memoirs offended him, including Ethel Mannin's Confessions and Impressions (1930) and Nina Hamnett's Laughing Torso (1932). These suits not only failed, they attracted a long line of creditors who were finally able to locate Crowley and bring him before the Official Receiver. In 1935, he was forced into bankruptcy.

During the 1930s and ‘40s, a group of devoted Thelemites in California operated the only active Thelemic O.T.O. body in the world. Agape Lodge conducted initiations, printed an edition of The Book of the Law , collected donations for Crowley's publishing efforts, and even sent him gifts of chocolates and Perique tobacco during World War II. One of the members, Captain (later Major) Grady Louis McMurtry (1918–1985), met Crowley while stationed in Europe during the war. Crowley was so impressed with this young man that he elevated him to IX° and made him his envoy, empowering him to take control of the O.T.O. in California and the U.S. if circumstances ever warranted it. McMurtry was instrumental in reviving the O.T.O. when it became moribund following the death of Crowley's successor, Karl Germer (1885–1962).

In his twilight years, Crowley proved as prolific as ever. His books Little Essays Toward Truth (1938) and Eight Lectures on Yoga (1939) are true gems of understated wisdom and clarity. He then spent five years collaborating with student and artist Frieda Lady Harris (1877–1962) to design a new tarot deck and its companion volume, The Book of Thoth (1944). The deck is a masterpiece, each card dense with layers of symbolism that keep emerging even after years of study; it remains one of the best-selling tarot decks in the world to this day. The Book of Thoth is no less magisterial, condensing forty-five years of occult study and practice into his most mature book on magick. Crowley next released Olla: An Anthology of 60 Years of Song (1946), a hand-picked selection of his best poetry. He rightfully remarked at the time, “I doubt whether anyone else can boast—if it is a boast—of 60 years of song.” 34

Aleister Crowley died on December 1, 1947, with chronic bronchitis finally taking its toll on his heart. Although he had been living in a boarding house—with a nurse available at the end only through the generosity of Frieda Harris—he died with four hundred British pounds in a strongbox under his bed, earmarked for the O.T.O.'s publication of Liber Aleph and Magick without Tears . Until the day he died, Crowley never wavered in dedication to his mission as prophet of the Law of Thelema.

Crowley's body of work is so large that it's hard to know where to begin. I've selected a “top eleven” list of books on magick that are essential reading for anyone who wishes to further study Thelema. In addition to the works listed below, my own biography, Perdurabo , provides a detailed look at his life.

Among his unique accomplishments, Crowley developed a system of classification for his writings that provides guidance to students of the value he placed on each of his books, and the states of mind he experienced during the process of writing them.

Regarding the classifications of the books listed below: Many include writings in various classes, such as The Equinox and Liber ABA. Some are modern compilations of Crowley's writings, such as The Revival of Magick. We do not assign classes to edited collections.

777 and Other Qabalistic Writings : Crowley's important writings on the Qabalah collected in one place. (777 itself is in Class B.)

The Book of Lies : Endlessly entertaining and enlightening. (Class C.)

The Book of Thoth : Crowley's last word on magick, an indispensable guide to his tarot deck. (Class B.)

Eight Lectures on Yoga : Perhaps the clearest explanation of yoga ever written. (Class B.)

The Equinox : This is really ten books (eleven with the “Blue” Equinox). You can also get Gems from the Equinox , which includes most of the key libri (books) from The Equinox.

The Equinox III(9) : The Holy Books of Thelema. The indispensable and accurate modern collection of the major Class A writings that define the spiritual system of Thelema. (Parenthetically, The Book of the Law appears twice. The typeset version is called Liber 220 , while the handwritten manuscript is Liber 31. )

The Equinox III(10) : Sold separately from The Equinox set, this modern volume collects the foundational documents of the O.T.O.

The Law is for All : Edited by Louis Wilkinson, this is Crowley's “authorized” verse-by-verse commentary on The Book of the Law .

Liber Aleph : This collection of letters to Crowley's Magical Son, Frater Achad, delves into some of the deepest mysteries of magick, sex, Thelema, and the Gnostic Mass. (Class B.)

Magick: Liber ABA, Book Four : If you buy only one book on this list, this is it. Crowley's masterwork on magick, with enough libri in the appendices to keep you busy for a lifetime. This modern collection, edited by O.T.O. Frater Superior Hymenaeus Beta, includes Book IV, Part 1: Mysticism; Book IV, Part 2: Magick; Book IV, Part 3: Magick in Theory and Practice; and Book IV, Part 4: The Equinox of the Gods. A great many supplemental writings are included as well. It is extensively illustrated, annotated, and indexed for exceptional ease of use.

The Revival of Magick and Other Essays : A delightful introduction to Crowley's philosophy, this is a collection of essays in which Crowley clearly explains magick and Thelema in nontechnical language for a lay audience.

1 Crowley, Aleister. The Confessions of Aleister Crowley. Abridged edition, John Symonds and Kenneth Grant, eds. London: Jonathan Cape, 1969, p. 35.

2 Tuck, Henry, Railway Directory for 1845: Containing the Names of the Directors and Principal Officers of the Railways in Great Britain , London: Railway Times Office, 1845; Glynn, Henry, Reference Book to the Incorporated Railway Companies of England and Wales , London: John Weale, 1847; Charles Barker & Sons, The Joint Stock Companies' Directory for 1876 , London: John King & Co., 1867.

3 Dickens, Charles, “Self-Acting Railway Signals,” Household Words 1853, 7(155):43–5; Anonymous, “Crowley's Safety Switch and Self-Acting Railway Signals,” The Mechanics' Magazine 1853, 58(1537):66–7.

4 Crowley, The World's Tragedy , p. xiii.

5 Confessions , p. 46.

6 Confessions , p. 36.

7 Confessions , p. 54.

8 The World's Tragedy , p. xx.

9 Confessions , p. 73.

10 Confessions , p. 113.

11 Confessions , p. 166.

12 Stephensen, The Legend of Aleister Crowley , p. 37.

13 W.B. Yeats to John Quinn, 21 March 1915, John Quinn Memorial Collection, New York Public Library.

14 Fuller, J.F.C. “Aleister Crowley 1898-1911: An Introductory Essay.” In Keith Hogg, 666: Bibliotheca Crowleyana: Catalogue of a Unique Collection of Books, Pamphlets, Proof Copies, MSS., etc., by, about, or connected with Aleister Crowley: Formed, and with an Introductory Essay, by Major-General J.F.C. Fuller , Tenterden, Kent, 1966, p. 8.

15 Amphlett Micklewright, F. H. “Aleister Crowley, Poet and Occultist.” The Occult Review 1945, 72(2):41–6.

16 Before achieving fame as the author of Of Human Bondage (1915), William Somerset Maugham (1874–1965) modeled the title character of The Magician (1908) after Crowley. French artist Auguste Rodin (1840– 1917) befriended Crowley for defending his sculpture of Balzac, and they collaborated on Seven Lithographs By Clot from the Water-Colours of Auguste Rodin with a Chaplet of Verse By Aleister Crowley (1907). Gerald Festus Kelly (1879–1972) was studying under Canadian impressionist James Wilson Morrice during this period; he would go on to be knighted in 1945 and to serve as president of the Royal Academy from 1949 to 1954.

17 Technically called Liber AL vel Legis .

18 The Sword of Song (1904) reveals that Crowley had begun identifying himself with 666 before receiving The Book of the Law . Magically speaking, there is nothing evil about the numeral 666. It actually symbolizes the Sun; because its traditional number is 6, so are its extensions 6x6 (or 36) and Σ(1-36) or 1+2+3+. . .+36 = 666.

19 Wells, Colin. “Something Wicked This Way Comes.” Rock and Ice , 136 (September 2004):60.

20 Whether he bitterly felt the mutineers got what they deserved, or whether he didn't realize exactly what had happened until morning, is unclear from Crowley's account.

21 The Greek Augoeides (lit. “Shining Image”) is a Neoplatonic term for the body of light known to advanced initiates; Crowley came to identify this term with the Holy Guardian Angel. Although the invocation itself is from a Greek magical papyrus in the British Museum, Crowley inserted it as a “preliminary invocation” to his edition of The Goetia (1904) and later based his “Liber Samekh” upon it. See the second, illustrated edition of The Goetia .

22

This occurred when he fell off his horse, tumbled down a ravine, and marveled at how he possibly could have survived. For the grade of Exempt Adept, see Chapter 2

on A A

A .

.

23 Fuller's motto Non Sine Fulmine is Latin for “Not without a thunderbolt.”

24 Jones unsuccessfully sued The Looking Glass newspaper for libel; see Kaczynski, Perdurabo Outtakes . Crowley's relationship with the British press is thoroughly examined in Stephensen, P.R., and Crowley, A., The Legend of Aleister Crowley: A Study of the Facts , with an introduction by Stephen J. King, Enmore, New South Wales: Helios Books, 2007.

25 p. 709.

26 As of this writing, the Vatican has announced publication of documentation of the Templars' trial, noting that it exonerates them of any heresies.

27 Perdurabo , p. 230. For a thorough examination of Crowley's intelligence claims, see Spence, Richard B., Secret Agent 666: Aleister Crowley , British Intelligence and the Occult , Port Townsend, WA: Feral House, 2008; Spence, “Secret Agent 666: Aleister Crowley and British intelligence in America, 1914–1918.” International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence , 13 no. 3 (2000):359–71. Additional information appears in The Legend of Aleister Crowley (2007), p. 16.

28

The Scarlet Woman is an office first mentioned in The Book of the Law

, I:15, “Now ye shall know that the chosen priest & apostle of infinite space is the prince-priest the Beast; and in his woman called the Scarlet Woman is all power given. They shall gather my children into their fold: they shall bring the glory of the stars into the hearts of men.” In “One Star in Sight” (see page 93 infra

), Crowley writes of members of A A

A that, “They must acknowledge the Authority of the Beast 666 and of the Scarlet Woman as in the book it is defined, and accept Their Will as concentrating the Will of our Whole Order.” He footnotes this and explains further, “‘Their Will’— not, of course, their wishes as individual human beings, but their will as officers of the New Aeon.”

that, “They must acknowledge the Authority of the Beast 666 and of the Scarlet Woman as in the book it is defined, and accept Their Will as concentrating the Will of our Whole Order.” He footnotes this and explains further, “‘Their Will’— not, of course, their wishes as individual human beings, but their will as officers of the New Aeon.”

29 Perhaps best remembered for her role in Mary Pickford's Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm (1917).

30 Hamnett, Nina. Laughing Torso . London: Constable & Co, 1932, p. 177. The Butts diaries in Yale University's Beinecke Rare Book Room (General MSS 487) recount the magical work she did at the Abbey of Thelema.

31 There is more to Crowley's expulsion from Italy than simply bad press, including internecine Masonic rivalry and the widespread expulsion of expatriates following Mussolini's rise to power.

32 His diary The Fountain of Hyacinth (a.k.a. Liber Nike , after the Greek goddess of victory) shows that he wasn't entirely successful in his attempts. Part-published in various places, the full diary appears in Crowley on Drugs (forthcoming). Because so much has been made of Crowley's heroin addiction, it is worth noting that Crowley became free of the drug in 1924, and did not use it again until 1940, when it was again prescribed to treat his asthma. He received government-controlled medicinal doses by mail until his death in 1947. Frequent descriptions of Crowley as a lifelong drug addict are false.

33 November 19, 1922.

34 Perdurabo , p. 447.