“Prescription without diagnosis is malpractice in any profession”

Bryan Flanagan, founder of Flanagan Training Group

You have a horrible cough and call your doctor’s office to ask the triage nurse to have your doctor refill the medicine for a cold and chest infection that she prescribed a year ago. After all, your symptoms are identical. If the doctor agrees to the refill, she is risking malpractice. Chances are, your latest cough may be related to the virus you had last year, but it may also be related to a host of other problems, which is why your doctor will likely want to examine you to do the proper diagnostic tests before calling in a prescription. While a trip to the doctor’s office may be frustrating, especially if your problem is what you initially suspected it was, you — and possibly your heirs — would most likely never forgive the doctor if her prescription treated the wrong illness and you became critically ill.

While many of today’s organizations are improving their ability to measure and diagnose problems, executives still tend to jump to the causes of problems, especially when dealing in people-related areas, where impartial fact-gathering is often very difficult and the consequences of poor judgments are often not immediately apparent. Such flawed analysis often results from inadequate measurement.

Consider the experience of a major pharmaceutical company with which I worked. The company had recently been third-to-market with a new HIV drug. This delay left the company with a small fraction of the market share and a relatively low return on the substantial money it had invested. A postmortem of the causes for the delays in launching the product revealed that several development teams had worked at cross-purposes. Two key scientists had also left the company in the middle of the effort, setting development months behind as new scientists joined the team. If the problems in Alignment and Engagement could somehow have been detected as they first occurred, the company could have taken quick action to remedy the situation. While knowing whether such action would have gained the company greater market share is impossible, few of the executives doubted that many months could have been shaved from the delivery schedule.

As is often the case, this pharmaceutical company created a negative spiral. Following the company’s failure in the marketplace, the Engagement level of employees in the research team dropped further. Additional talent left the organization. Others felt burned out by the frustration of working so hard, only to finish a distant third behind swifter competitors. The mad dash to the finish line had left little time for employees to learn new skills, since any discretionary time was spent on infighting and working to integrate new team members into the effort. As employees became more cynical, productivity diminished even further. Bottom line: Many, if not all, of these problems might have been avoided if effective measures had identified these problems and risks much earlier so that corrective actions could be taken.

How Can We Measure Talent Optimization?

The best way to measure talent optimization — and avoid the types of problems faced by the pharmaceutical company — is to measure ACE and whatever drives it. We at the Metrus Institute believe that ACE captures 80 percent or more of optimized talent (being all you can be) as described in Chapter 3. This chapter focuses on how to measure People Equity, or ACE.

Although we and others have experimented with different ways to measure ACE, using a variety of instruments such as alignment audits and competency banks, we have found the most direct and cost-effective way is to use survey methodology.1 Based on our research and experience measuring ACE in organizations, we continue to be impressed by how much information about People Equity is possessed by employees or other labor sources. They can accurately describe many aspects of the following:

We have found surveys work for the following reasons:

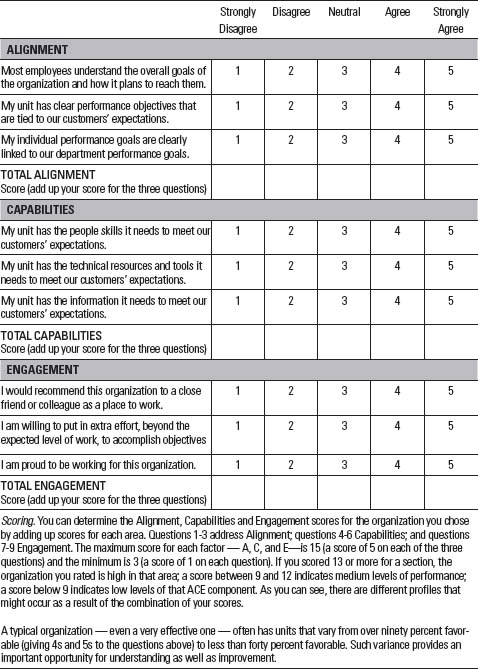

Depending on the level of sophistication needed, an ACE questionnaire can range from a short pulse survey of ACE (see Table 7.1) to a more informative look at the many drivers and enablers of ACE. The former is good for temperature tracking of the essential A, C, and E elements to help raise red flags; the latter provides greater insight about ACE, why it is high or low, and how exactly to improve it.

How does an ACE survey differ from other “employee satisfaction” or “engagement” surveys?

A short list of typical questions included in an ACE survey is displayed in Table 7.1.2 To give you a hands-on understanding of ACE, try answering the sample questions for an organization with which you are familiar. Rate each question from Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree.

Table 7.1 A Sample Set of ACE Questions

The Drivers and Enablers of ACE

A frequent question is whether an organization can get away with using a low number of questions (such as 12) for the survey. While you can capture the essence of ACE with 10 or fewer questions, such a short instrument will not allow you to meaningfully identify why A, C, and E are high or low. It would be like looking at a turnover number and simply guessing why the number is so high without seeking additional information. Adding driver and enabler questions adds precision to the analysis, which in turn helps managers quickly focus on promising areas for attention.

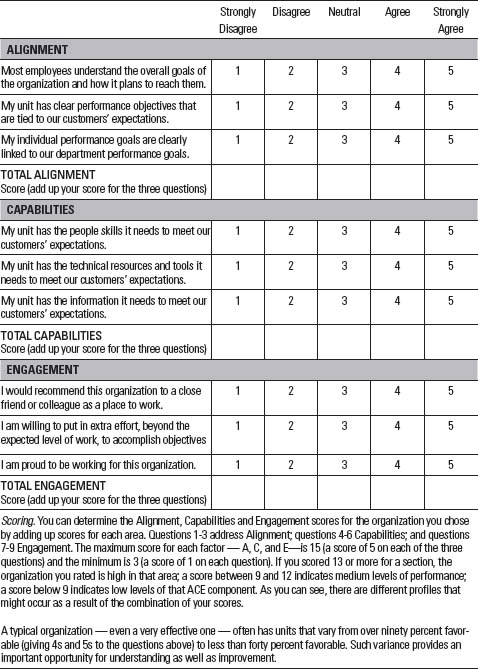

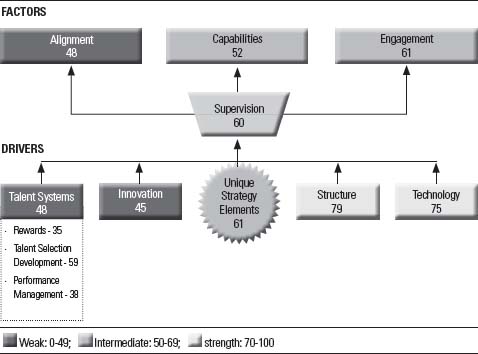

Figure 7.1 shows five common drivers and four common enablers of ACE, although these can vary from organization to organization. The five drivers are typically more directly connected to either A, C, or E and represent factors that more narrowly improve a single aspect of ACE. For example, training (included with Talent Systems in Figure 7.1) typically has the most direct influence on Capabilities, while the performance management system — another key Talent System — in most cases has its biggest influence on Alignment because it clarifies goals, sets targets, and provides performance feedback.

The four enablers (Leadership, Values/Operating Style, Direction/Strategy, and Supervision) are typically more general influenc-ers of all ACE areas as well as many of the drivers. The immediate manager or coach is one of the most influential enablers of multiple ACE components, but he or she can only operate within the policies, systems, and practices endorsed and supported by senior leadership. Supervisors, for example, have a direct effect on Engagement by how they communicate and treat people, and they strengthen Capabilities by matching talent with jobs and arming employees with sufficient skills, information, and resources to succeed. They also enable Alignment by how they set performance targets, coach, and link pay to performance.

Top management influences many areas as well. Leaders who live the organizational values create a positive environment. They also set the strategy and work with groups such as HR to create policies, systems, and practices that either enhance ACE or detract from it. For example, if you have new hires who value openness and transparency but view top management as secretive, Engagement scores are almost certain to be negatively affected.

Figure 7.1 Drivers and Enablers of People Equity (ACE)

While using a standard set of driver and enabler questions is feasible (see examples in Table 7.2), is it necessary to ask about them all in the survey? The answer is predicated on strategic and statistical analyses that can help eliminate questions that do not add any predictive value or that are unlikely to be strong drivers or enablers for a particular organization. A Great Practice is to start with a more comprehensive set of drivers and enablers, and then winnow them down after having strategic talent discussions with senior management and HR. The first round of surveying can then be used to statistically confirm drivers and enablers with the greatest predictive power.

Table 7.2 Topic Areas Often Addressed in ACE Surveys

| Factors of People Equity | |

| Alignment |

|

| Capabilities |

|

| Engagement |

|

| Drivers of People Equity | |

| Talent Systems |

|

| Technology |

|

| Innovation |

|

| Structure |

|

| Unique Strategy Elements |

|

| Enablers of People Equity | |

| Supervisory/Direct Manager |

|

| Leadership |

|

| Direction/Strategy |

|

| Values |

|

Measuring ACE does not need to involve a tremendous amount of work. The short version of an ACE survey can contain as few as nine questions. Longer, more insightful, versions that include drivers and enablers may contain 25-40 questions, a length that can typically be completed in less than 20 minutes by most employees.

Standard versus Custom Questions

Should you use an off-the-shelf list of ACE questions, or should they be customized for your organization? The answer depends somewhat on your purpose for conducting the survey. If your goal is simply to take a simple measure of the organization’s temperature, a short list of standard questions may suffice. In contrast, if your goal is both to identify the overall level of A, C, and E and to evaluate the unique aspects of ACE related to your business strategy and culture, then custom questions will help.

Custom questions are also often helpful to gain buyin from senior executives. For example, in a restaurant group, the senior executives were concerned about specific issues related to food quality and safety. Therefore, the company’s survey contained unique questions to measure employee understanding and acceptance of these issues.

Also, Engagement in varied environments may be driven by different factors, requiring different driver measures. For example, an important driver of Engagement is often an employee’s agreement with the values exhibited by the organization. We could simply ask how well the organization is living its values; however, it is usually more valuable to ask specific questions about their specific values such as food safety, customer intimacy, or innovating.

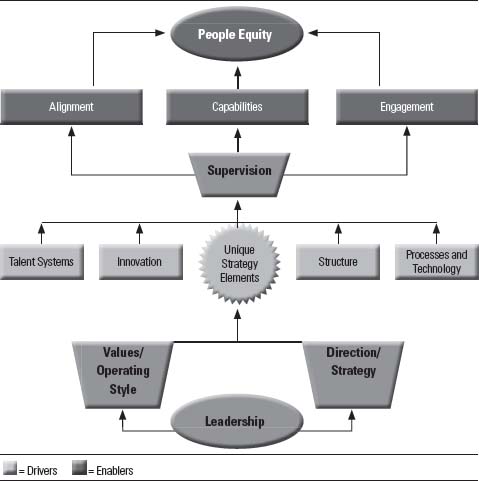

Take a look at Figure 7.2.

Figure 7.2 Employee Engagement Scores

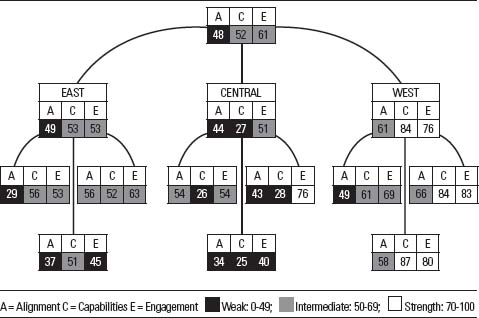

This is a profile, taken from an employee survey, of an organization’s Engagement index scores from three different regions. Engagement scores could range from zero to one hundred.3 This simple snapshot provides a viewer with some compelling information. What would you conclude about this organization?

One insight is that the West region has found a way to engage people at a higher level than other regions, although one unit in the Central region also demonstrates positive Engagement (a score of 76). Another insight is that there is a great deal of variance across the organization regarding Engagement. This observation is interesting given the fact that every unit has the same type of people and uses the same talent systems for hiring, selection, training, performance appraisals, and pay. The distinctions suggest the possible influence of different managing practices.

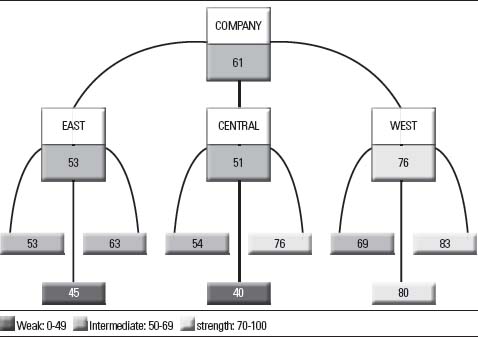

In Chapter 3, we described the eight profiles of People Equity defined by combinations of high and low scores on each factor of A, C, and E. Figure 7.3 provides a more informative look at the same organization represented in Figure 7.2.4 This view provides leaders with far more valuable information regarding their workforce compared to viewing Engagement alone. Figure 7.3 provides index scores from a survey for all three ACE components, again with possible scores between zero and 100. The shading indicates areas of strength, weakness, or intermediate performance for each dimension, while the numbers provide more detailed data. This more complete picture reveals a number of new insights; take a moment to see if you can uncover them.

Figure 7.3 The ACE Scorecard™

Assume you are the general manager responsible for the three regional divisions depicted in Figure 7.3. What are the major themes, and what action would the figure lead you to consider?

This ACE Scorecard™ chart helps organize information about how effectively human capital is being utilized throughout the organization. The profile suggests some concerns for the manager to think about:

Such information enables senior leaders to form a number of hypotheses and make some important decisions.

Where to Direct Organization-Wide Attention and Resources

The HR organization was about to launch a company “engagement” initiative that included training for all managers. These data helped the HR team refocus and target their training. The Engagement training was redirected to a subset of units for which the initiative would be most valuable, while additional resources were redeployed toward communicating the strategy and improving goal-setting. HR also set out to investigate what Engagement “Great Practices” were being used in the West Division to generate such strong scores.

Alignment scores were lower than Capabilities and Engagement scores in every division. Clearly, this was the weakest dimension across the entire organization. Low Alignment across the organization points to a disconnect in the line of sight from strategy to unit goals to individual accountabilities. But without looking more deeply into the root causes for low Alignment, it is unclear whether every unit has low Alignment for the same or different reasons. Fortunately, in this case, a more comprehensive survey — one that includes not only ACE but also its drivers and enablers — pointed managers toward the root causes and solutions.

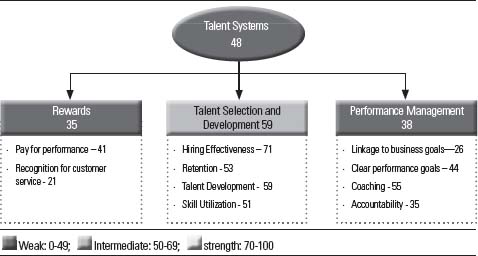

As depicted in Figure 7.4, scores from the survey on specific drivers and enablers identified two of the drivers (Talent Systems and Innovation) as weak. By drilling down one more level within Talent Systems, for example, it became evident that the Performance Management and Rewards systems (not Talent Selection and Development) were the weakest.

When the top-level ACE results were shown to the leadership team, before seeing driver and enabler scores, several function heads speculated to the rest of the team that the low scores were probably the result of poor performance coaching. Another voice concluded that it was due to weak recent hires. But the data proved otherwise, saving this organization from perhaps being swayed by one or two vocal leaders with misleading conclusions. By drilling down one more level under Performance Management in Figure 7.5, to the scores on the survey driver items that support Performance Management, it became clear that the biggest gaps were goal-setting and accountability. In the low-scoring area of Rewards, lack of recognition was a major culprit.

Figure 7.4 Example Scores on Drivers and Enablers of ACE

The leadership team was surprised and impressed at its ability to get to the heart of the gaps that inhibited talent optimization quickly. Instead of channeling resources to coaching or selection, or spending countless hours troubleshooting likely causes, management was quickly able to target resources to these gaps. We recommend deeper discussions or the use of focus groups to further pinpoint the issues and to identify examples of particularly good and weak performance, so that fixes are specific, relevant and aimed at removing root causes.

In this case, the corporation redoubled its effort at communicating the strategy and direction. In addition, top executives discovered that the communication of the strategy contained disconnects from top to bottom. They adopted a cascaded balanced scorecard as one of the tools to improve the flow of communication. The scorecard focused the top team on the critical drivers and enablers of value for the business; the cascading allowed each business unit and department to connect their goals and measures to the overall strategy and direction. This approach proved a major help to managers in carving out smarter and more understandable goals with their people.

Figure 7.5 Scores on the Driver and Enabler Questions Supporting Rewards, Talent Selection and Development, and Performance Management

Where to Target Solutions

In contrast to the broader Alignment gap, the Capabilities challenge required more pinpointed interventions. A Capabilities driver analysis suggested that employees in some units with low Capabilities needed additional job coaching. In other areas, weak staffing and poor teamwork appeared to be the culprits. In yet others, poor implementation of a recent training program seemed to have been a contributor to the problem.

Where to Focus Leadership Development Efforts

The ACE Scorecard™ diagram in Figure 7.3 highlights the relative strengths and weaknesses of managers regarding their performance in optimizing human capital. When combined with market and financial performance, this information provides valuable feedback on leadership performance and potential.

For example, Tom, the Central region’s leader, was a high flyer recruited from another firm who joined the company approximately a year before the survey. The ACE survey information summarized in Figure 7.3 was certainly disconcerting to both Tom and the leadership team. Tom was clearly struggling to connect with his people. Given this organization’s value to “get close to the people,” this discovery was especially troublesome.

The assessment put both Tom and the leadership team on notice that something was amiss and needed to be addressed. Jonathan, the president, immediately began to focus more attention on the Central region, offering Tom additional coaching and resources. He also monitored developments in the Central region more closely and discovered that the division was experiencing increased turnover, complaints to corporate HR, and an employment lawsuit filed shortly after the survey. The alert provided by the survey served as a wake-up call for Tom, providing him with time to correct the situation.

I asked the reader earlier to consider the fact that one unit in the Central region received a relatively positive score of 76 in Engagement, while receiving low Alignment and Capabilities scores. Did you come up with a possible reason why the region might have such a profile?

If you guessed that the unit was newly created, that was a good guess. In such cases Engagement is typically at its highest, while Capabilities and Alignment are frequently lower. This was not the case in this particular example, however. In this case Rich, the head of the unit, was misaligned with his boss and many of his peers. He had built a unit that was very loyal to him but not to the overall organization. A “we versus they” microculture developed as a result. Rich had carefully protected people with low competencies from the scrutiny of others, especially if they were loyal to him (note the low C scores). As for low Alignment, an analysis of the drivers and enablers revealed that the Alignment questions relating to Rich were relatively positive, while those related to Alignment with the larger organization were low. When combined, the two scores lead to a middle-of-the-road score of 44 percent favorable.

By the time the survey was taken, the marketplace was beginning to note the problems. The lagging indicators of customer complaints and disloyalty began to climb, as did internal conflicts between Rich’s unit and others in the organization. When Rich left a few months later, the unit imploded. Many people left within a few months, providing testament to where their loyalties lay.

Over time, information on A, C, and E can be helpful in assessing the impact of leadership development investments. If these help move People Equity scores, they increase return on investment; if not, it is time to revamp the activities or change managers.

Where to Invest in Talent to Boost Employee Retention,

Customer Loyalty, Operational Effectiveness,

Quality, and Financial Performance

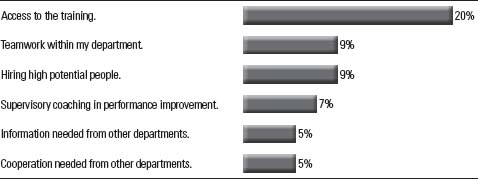

Driver analyses, using advanced statistical techniques, can help identify whether improvements in A, C, or E — or the drivers of ACE, such as increased rewards, additional training, or leadership communication — are likely to have a significant impact on important outcomes, such as employee or customer retention, productivity, and customer loyalty.

For example, in the organization being discussed, such an analysis identified respect and dignity as key drivers of Engagement. This finding was supported by focus groups we conducted in the Central region where lack of respect was a commonly discussed issue.

In another company, where Capabilities scores were both low and closely related to turnover and customer complaints, a driver analysis identified that improved job training would be twice as powerful a driver of Capabilities as improved teamwork, among the many possible actions the organization could take (see Figure 7.6).

Figure 7.6 Drivers and Enablers of ACE: Relative Importance

Where to Hold, Fold, or Increase Prior Investments

The ACE Scorecard™ diagram also provides useful data about past investments. If initiatives have been deployed in the past, did they result in improvements? If not, perhaps they need to be redesigned or eliminated.

In the case of Tom, the Central region manager, resources were diverted to help him succeed — coaching, additional support on labor issues from HR, communications assistance from the corporate office, and additional training resources to enhance some of his marginal performers. And yet, after the next round of surveying, his scores had improved only marginally — trust remained an issue. At that point, Jonathan, the president, faced a tough decision. He recognized that low People Equity scores, marginal financial performance, and declining customer ratings raised serious questions about the new leader.

I want to emphasize that measurement of ACE is not primarily about weeding out poor managers. It is about understanding why and how an organization is optimizing its talent. ACE provides baseline information that — together with benchmark data — enables managers and the organization to determine where it can improve. Great Practice organizations use the information to identify opportunities for improvement and then work with managers and HR to adjust practices, programs, policies, and behaviors in ways that better optimize the use of their talent.