“Talent is not captive — it’s easier and less costly to develop and retain top talent than to find new talent”

Wayne Cascio, Professor, University of Colorado Denver

The CEO of a manufacturing organization lamented the shortage of leaders ready for top positions — a typical gap in bench strength. He was increasingly frustrated because he felt that previously identified high potentials and recently promoted managers were not arriving at upper middle management levels “leadership ready.” When the CEO saw the ACE scores of managers across the organization, his frustration changed to deep concern: “How can we have so many managers who are low on A, C, or E — and worse yet, all three?” Furthermore, the organization was taking on water — leaders and professionals in key jobs were leaving at an increasing rate, and the organization rarely recovered any of this talent once it was lost.

The roots of these problems lie in several stages of the talent lifecycle. Performance reviews apparently had not been effective in improving performance, but they had been effective in lowering Engagement, resulting in some early departures. And many managers were getting “passing grades” while their ability to optimize talent within their domain was subpar. Was the organization identifying the “right” high potentials for leader development? And if so, why were these leaders not able to attain higher ACE scores from the people they were entrusted with? Leaders need followers, and a glimpse at the leadership questions in the ACE survey suggested that many of these leaders were not inspiring employees, not setting stretch targets, and not retaining people because of meager development opportunities and lack of recognition. And the outcome of this leadership chasm was the departure of many high performers that the organization valued.

In the last chapter, I used the ACE lens to discuss talent onboarding, training, and performance management processes and actions that could be taken in each area to increase ACE and optimize talent. In this chapter, we look to the future to ensure that we develop the leaders we need for success, retain high performers, and recover targeted talent.

Developing Leaders

Fast Facts

The ACE Perspective

Insufficient talent. One of the biggest areas of interest to the majority of executives interviewed for this book was leader development and succession. Most of these executives admitted that the talent identified or prepared to take the next step was insufficient. As we saw in Chapter 6 on preparing managers for a high ACE organization, a wide variation in talent optimization skills exists in most organizations, and there are many talent blind spots. Before turning to the outside for instant leadership skills, an organization needs to focus on developing its high potentials and current managers to become stronger at the “how” of getting results through the optimization of talent.

Another key decision involves the length of time to enable managers to become high ACE leaders. I am continually surprised and disappointed to find managers who perennially get low people scores on their ACE survey or their 360s, and yet senior leaders allow them to continue to deplete the talent pool because they have achieved short-term results. Actually, in a number of recent organizational audits conducted by the Metrus Institute, we found that many managers with low ACE scores in their organizations have failed to get even short-term results. Based on our experience, most of these managers eventually wash out either in their current role or when they are moved to a role that demands even more people skills.

One engineering organization found it necessary to move many second-level managers to technical roles because it could not develop the people skills needed to be successful — sadly after many good engineers and scientists left or transferred to more engaging leaders. We offer two suggestions:

Leadership development — like performance management — needs to be continuous. As I have noted earlier, with today’s pace of change, staying the same means that competencies and organizational Capabilities degrade. If individuals are becoming obsolete, this inevitably affects their levels of Engagement. Often we hear the comment, “The work load is so high that I can’t take the training I should.” This is a dangerous game for the organization — one that maximizes today’s performance at a cost of depleting tomorrow’s. Ask your team whether you have given sufficient attention to leader development. Better yet, ask your high potentials how they feel.

A closely related issue is when to develop leaders. Professor Peter Cappelli at The Wharton School argues that training someone before there is a need or chance to use the skills involves risk. This is a case of poor role Alignment. The old model entailed putting highpotential leaders into a variety of structured training programs, but the risk today is that the structure of those programs does not match the fast pace of changing skill needs. Develop additional competencies too early, Cappelli tells us, and the talent is likely to take your training and apply it elsewhere, perhaps with a competitor. His data suggests that recently developed leaders who are unable to deploy their newly learned skills leave the organization in 10 months on average.1 Essentially, we have increased the Capabilities while Alignment with assignment is mismatched.

This research points to a need for more just-in-time training and for more agility in having resources available as leaders need them for learning. Examples might include fast-track training for a new assignment in Shanghai, cultural training for a manager in India being assigned to Los Angeles, or high-level drug development training for a leader coming to a pharmaceutical company from the medical diagnostics business.

Highpotential and high-performing people should be assessed regularly. Training and development of highpotential leadership candidates should be started early, but with more general skills such as industry and business acumen and talent optimization skills. Given that 70 percent of learning occurs on the job, assignments should be carefully selected to maintain the Engagement of these managers, hone new skills (Capabilities), and open up new insights about the organization (Alignment). Specific skills should be added on a just-in-time basis. And the retention likelihood of these highpotential and high-performing people should be assessed regularly. Only with such integration can talent be optimized.

Using the talent lifecycle framework developed by the Metrus Institute, we can see the need to have a seamless connection between an organization’s hiring expectations — for example, bring aboard a fast-track leader — and early training, ACE performance reviews, and subsequent leader development. In some organizations we examined, their executive recruiting firms were still focused on bringing in candidates who had high competencies — a key ingredient for Capabilities — but were not seen as sufficiently identifying candidates who fit into the culture (Alignment) or who displayed the potential to be high Engagement talent. Someone who is philosophically committed to a customer intimacy approach will have a hard time truly buying into a high-volume, low-service business model. Once good prospects are identified, then selection, onboarding, and acculturation processes need to be well connected in terms of messaging.

Organizations and their recruiting firms should also assess for future potential, in addition to current fit and capabilities. A far better investment is to bring in talent that can not only serve today’s needs but also be groomed for the future. Selection of leaders from a well-known internal pool is typically far more successful — some estimates suggest two or three to one — than hiring from the outside. One reason for such success is that we know far more about the Alignment and Engagement dimensions of someone who is already in the organization.

ACE thinking is ideal for determining high potentials. Do the individuals whom we have identified possess a strong track record of high Engagement and Alignment, in addition to Capabilities and individual performance results? Have we included those criteria in our early assessments? And if these individuals meet those criteria, what evidence do we have that they can create a high ACE organization under their leadership? Look at the teams in which they have worked. Do they create commitment, energy, and advocacy with others on the team? Can they help the teams stick with the primary goal, rather than divert into side issues?

Recent data by Karen Stephenson suggests that we can also identify candidates who probably should be “high potential.” Her work in understanding network patterns suggests that we can find the true informal leaders who command connectedness and fol-lowership from others. They are people who are at the crossroads of communications rather than simple gatekeepers whose power resides in the ability to restrict others.

Retaining High Performers

Fasts Facts

The ACE Perspective

While our research and that of others have shown that turnover costs vary widely across industries and organizations, we often find in our interviews that most managers and executives grossly underestimate the real cost of turnover.2 Some organizations simply neglect to calculate such costs. For others, it is not uncommon to find that actual turnover costs are three to four times what members of an organization estimate them to be. When executives and managers fail to calculate such costs accurately, they are likely to ignore this area of opportunity.

Why are cost estimates so far off? The primary cause is failure to include the indirect and intangible costs. While not insignificant, advertising, recruiting, and separation costs are relatively low compared to training and productivity losses incurred when a new employee has to be brought in and up to speed. The ramp-up time for a replacement employee to reach full performance can be quite substantial. And while current employees may pick up the slack in the short run, they fail to complete other tasks. This situation tends to decrease the Engagement of these employees, risking the loss of effort, quality, and retention of these overburdened individuals.

Even the analyses that consider ramp-up costs often fail to consider costs incurred in other phases of the talent lifecycle. For example, what are the costs when an heir apparent to a key role departs? Developmental and succession gaps are obvious costs. Less obvious are the hidden costs, such as the impact on the organization of an informal thought leader’s departure. What is the impact of his or her lost knowledge, experienced decision-making, access to inside networks, and so forth? Looking at the entire talent lifecycle helps us understand many of the hidden and intangible costs as well as the apparent ones.

A final cost often neglected is the risk to customers, stakeholders, or the brand. Did we lose customers or their loyalty during the transition? Did we lose sales? Even if the role is internal — say an HR sales trainer — did we delay training for new sales people that perhaps is costing us revenue? Or in the transition of a billing person, did we make errors or have delays in customer billing that is costing the organization money?

Putting our ACE lens on, we must recognize that high ACE employees are often the most sought-after targets by other companies — they are your best employees! The good news is that they are also resistant to leaving. But many firms do not do a good job of identifying “retention hot spots,” such as departments or classes of individuals such as high performers and those with scarce technology skills. The ACE survey can be a good tool, especially if a retention index is created from a subset of the ACE driver questions. Changes in Engagement are often highly predictive of turnover, so the first place to look for turnover risks is a unit with low or declining Engagement.

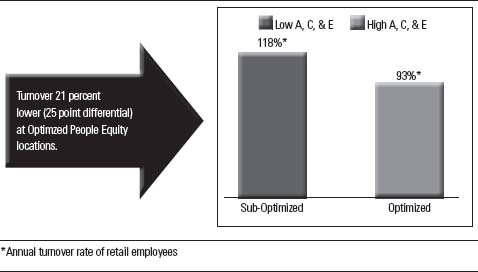

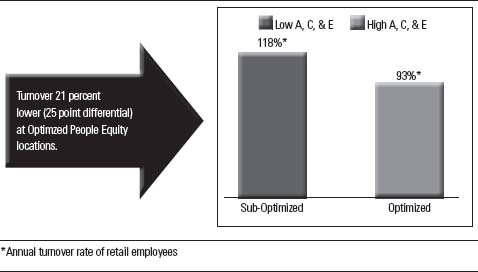

However, Engagement is not the only leading indicator of turnover risks. Figure 12.1 displays the results of a recent survey analysis of the impact of ACE on turnover in the retail industry. In high ACE units (approximately the top quartile), turnover is 21 percent lower than in low ACE units. For these lower units, this figure amounts to over $6 million dollars annually in direct costs alone. At a conservative multiple of two times direct costs for loaded and indirect costs, having all sub-optimized units would cost the organization over $12 million dollars annually.

Figure 12.1 Impact of ACE on Annual Turnover

Figure 12.2 shows us that nearly half (49 percent) of actual turnover can be predicted by knowing ACE. And of the ACE factors, Capabilities is the largest contributor (46 percent) to turnover, followed by Engagement at 30 percent. This organization was then able to drill down to the items that drive high Capabilities to discover that weak training was one of the biggest culprits leading to turnover.

Figure 12.2 Contribution of A, C, and E to Controlling Turnover

Surveys cannot provide all the answers. In high-risk locations or units, having retention discussions with your best people is a healthy strategy. These interviews can gauge the likelihood of a high performer staying, and better yet, open up the possibility of intervening to address issues before they leave. The ACE framework can help identify points of discussion. Remember to consider organizational “stickiness”: What are the biggest factors that keep your people here? Often, you will find some systemic factors that can be leveraged across the workforce. But retention is also a personal matter — one that requires thinking about the individual’s career desires or family needs against what the organization has to offer. Organizational drivers of ACE are not always the same as an individual’s personal drivers.

Organizations should also ascertain why people are leaving in their “A” or pivotal job groups. Are there systemic reasons? Are they controllable? Most firms rely on exit interviews to answer these questions. Unfortunately, about 50 percent of exit interview information is plain wrong.3 Few employees will burn bridges by discussing a supervisor from hell, unfair treatment, or other sensitive matters. By the time you talk to them in an exit interview, departing employees are already in another mindset — that of their new employer.

While some firms do a good job of extracting the most they can during the exit process, we find that far better information can be obtained after the dust has settled. Once a former employee has been working for a new employer for three to nine months, it is possible to hear a much more candid view of both your own organization as well as a comparison to where the employee is working now. Often the grass is not as green as perhaps the employee originally thought, or the employee can more objectively discuss strengths of your organization that he or she would have ignored at the point of exit. Capturing the longer perspective in this manner can be beneficial in understanding systemic root causes so you can better address them.

Without question, turnover can be managed better by most organizations. Firms such as Chevron have created retention tool kits to help managers hold on to key talent. At Chevron, the company targets valuable employees (high potential, critical skills, key roles, and difficult to replace) and high-attrition risk people — those assessed as having the propensity to leave. Managers at Chevron are trained to have focused discussions with high-risk individuals, and they are provided with a toolbox of alternatives — including monetary (such as pay, promotions, or stock options) or nonmonetary (such as new assignments, alternate work schedules, telecommuting, or leaves) — to create incentives for someone to stay longer with the organization. This approach gives a manager flexible options to work with a high attrition risk individual to find a win-win solution to keep the individual engaged with the organization.

Recovering Top Talent

Fast Facts

A newly emerging area for many organizations is recycling talent. If you have gone through the effort of finding the talent, developing it, and aligning it with your organizational goals and values, then retaining that talent for as long as possible would be ideal. And for those valued employees who depart, why not reach out to lure them back? Yet today most organizations treat an employee’s departure as the end of line. In fact, a telecommunication executive with whom I recently spoke said “If they leave, we essentially tell them to not let the door hit them in the behind on the way out. They are dead to us.” A strong statement, but one that frankly reflects the thinking of many organizations from Fortune 100 companies to Mom-and-Pop shops, where loyalty is valued above all else. “How dare they sell out!” is a sentiment widely echoed, particularly if an employee leaves for a competitor.

Here is where we can take a lesson from closed-talent markets like Hawaii or rapid-growth environments such as China. In Hawaii, much of the talent on the islands must be recycled because there is little movement between Hawaii and the mainland U.S. or other countries. Real estate and the cost of living today are highly prohibitive of talent flow. In China, the driving force is not so much geography and cost of living, but opportunity. Even professionals leave organizations on average in less than two years. In such an environment, how can an organization maintain a sufficient supply of top talent? In both communities, organizations are more accepting of and adept at recycling talent. They do far more to ensure that good employees leave with favorable impressions of the organization. They also build better systems to stay in touch with former employees. Today, staying connected is easier because of online groups such as LinkedIn that employees increasingly join.

Although it may require swallowing one’s pride, bringing back former employees has significant advantages. Besides gaining insight into the operations of competitors, returning employees are likely to be far more honest in discussing their reasons for leaving. In addition, they may come back more mature and with more realistic expectations. They already know the organization and are more likely to be aligned with its cultures and value. Besides the new experiences and Capabilities they bring, they will be more Aligned and Engaged than most new hires — a powerful combination!

These last four chapters have focused on the power of ACE and the talent lifecycle for thinking about how to design, coordinate, and execute various activities across the full spectrum of talent management processes.

Action Tips