Hieroglyphic writing is a complex system,

a script all at once figurative, symbolic, and phonetic,

in one and the same text, in one and the same

sentence, and, I might even venture, in one and the same word.

(Jean-François Champollion, Précis du système

hiéroglyphique des anciens Égyptiens, 1824)

Upon arrival in Paris on 20 July 1821, an exhausted Champollion settled down with his brother and family in their rented house at 28 Rue Mazarine, a central address in easy walking distance of Champollion-Figeac’s office at the Academy of Inscriptions and Belles-Lettres, within the French Institute. The situation of the 30-year-old Champollion after leaving Grenoble for Paris is reminiscent of that of the 10-year-old boy after he left Figeac and arrived at his brother’s apartment in Grenoble. In both instances, he was dependent on his brother for money and for the necessities of life. But, whereas in 1801 his elder brother had also been his teacher, now the relationship was reversed: Jean-François had become the teacher, Jacques-Joseph the pupil.

Over the next two years, in the house on the Rue Mazarine, without the distractions of university and school teaching, librarianship and the political instability of the previous decade, Champollion was able to devote his every waking minute – and probably his dreams as well – to ancient Egypt. Here, surrounded by his brother’s library and immersed in new sources of Egyptian writing on monuments and papyri that reached him from private and public collections in Europe and from travellers in Egypt, he would finally crack the code of the hieroglyphs. His results would be announced, hot off the press, so to speak, in lectures during 1821–23 – most famously on 27 September 1822 – delivered to the Academy of Inscriptions, thanks to his brother’s intimate connection with the academy’s long-serving secretary, Bon-Joseph Dacier; and in two crucial illustrated texts published in 1822 and 1824.

Unfortunately, the steps that led to his decipherment are hard to discern. The difficulty arises partly, no doubt, from a dearth of correspondence by Champollion in this period, during which he no longer had any need to write revealing letters about ancient Egypt to his brother or to fellow scholars, most of whom were now readily at hand in Paris. But it comes also from the fact that he left important aspects of his thinking in the dark, reporting chiefly his established conclusions in his lectures and publications. This obscurity in itself is not too surprising. Exceptionally creative minds such as Champollion’s generally work alone and in private: even the individual is often unaware of his or her own thought processes. Sometimes, however, Champollion’s silence about the source of his insights appears to have been polemical subterfuge, intended to diminish the importance of the work of his English rival, Young.

House in the Rue Mazarine, Paris, where Champollion was living with his brother’s family at the time of his breakthrough in decipherment in September 1822.

(Photo Roger-Viollet/Topfoto.)

To give a step-by-step account of Champollion’s decipherment in 1821–24 is therefore impossible. It is possible, though, to identify three general phases; then, looking more closely at the order in which he tackled the problem, one can use informed speculation to fill in missing sections of his own account. By bearing these phases in mind, we can avoid the confusion present in many published accounts of the decipherment, which rely on an incorrect date stated by Champollion’s first biographer, Hartleben.

In the first phase, lasting from April 1821 to September 1822, Champollion was convinced that all of the Egyptian scripts – hieroglyphic, hieratic and demotic – represented things or ideas, not sounds. This was the belief he stated in his Grenoble publication of April 1821, as mentioned earlier. He repeated it categorically a year and a half later on the first page of his Lettre à M. Dacier, which was based on his lecture at the Academy of Inscriptions on 27 September 1822: ‘I hope it is not too rash for me to say that I have succeeded in demonstrating that these two forms of writing [hieratic and demotic] are neither of them alphabetic, as has been so generally thought, but ideographic, like the hieroglyphs themselves, that is to say, depicting the ideas and not the sounds of the language.’ Although this statement seems to exclude even the slightest element of phoneticism from the Egyptian scripts, such a total exclusion was clearly not intended by Champollion, because he made one vital exception: hieroglyphs could represent sounds, not ideas, when they were used phonetically to write foreign proper names in cartouches, such as Ptolemy and Berenice. The latter deduction provided the raison d’être of his Lettre à M. Dacier, which proposed phonetic transliterations for the cartouches of many Greek and Roman rulers of Egypt, and a hieroglyphic and demotic ‘alphabet’ supposedly used only for writing foreign names.

During the second phase of decipherment, from September 1822 to April 1823, Champollion radically changed his mind. Having thought to apply his hieroglyphic alphabet first to the signs in native Egyptian cartouches, and then to other native Egyptian words, he was surprised and thrilled to find that the alphabet produced credible transliterations of historically known pharaohs such as Ramesses and Thothmes, and of ordinary Egyptian words recognizable from Coptic vocabularies. In April 1823, he announced to the Academy of Inscriptions that there was, after all, a major phonetic component in the hieroglyphic script, which had existed not only in the Greco-Roman period, but also throughout Egyptian history, and which had been used not merely in the writing of foreign proper names, but also throughout the script.

During the third phase, from April 1823 to early 1824, Champollion intensively worked out the hieroglyphic writing system, which consisted of a basic alphabet of some twenty phonetic values (the majority of them represented by several equivalent signs), some other, partially phonetic signs, plus many hundreds of non-phonetic figurative and symbolic signs. He showed how these phonetic, figurative and symbolic signs were combined to represent words by applying the system to numerous inscriptions, with consistent results. This analysis was published in his revolutionary Précis du système hiéroglyphique des anciens Égyptiens in April 1824, and in a revised second edition in 1828. The revised edition incorporated the text of his Lettre à M. Dacier (as its second chapter) but with a crucial emendation. Revealing his change of mind about phoneticism in 1822–23, Champollion silently, without so much as a footnote, altered the statement he made in September 1822 into a fundamentally different assertion that corresponded with his third phase of understanding: ‘I hope it is not too rash for me to say that I have succeeded in demonstrating that these two forms of writing [hieratic and demotic] are neither of them entirely alphabetic, as has been so generally thought, but often also ideographic, like the hieroglyphs themselves, that is to say, sometimes depicting the ideas and sometimes the sounds of the language.’ (His 1828 alterations are underlined.)

The credit for the second and third phases of the decipherment belonged, without question, to Champollion – a view not disputed by Young, who in fact never wholly accepted the phonetic component in the hieroglyphic script proposed by Champollion, other than in the spelling of foreign proper names. The dispute that arose between them concerned only the first phase, for which Young claimed far more credit than Champollion was willing to give him. Since the first phase laid the foundation for the subsequent decipherment, its authorship was bound to be controversial.

What influence did Young’s work of 1814–19 have on Champollion’s first phase? There can be no definitive answer. Indeed, the issue has been debated from 1823 until the present day; opinions of Young’s importance to Champollion’s decipherment cover the gamut from sine qua non to none.

French writers have almost universally subscribed to the view that Champollion was intellectually independent of Young – at least those who wrote after the decipherment became generally accepted in the mid-19th century. They have taken their cue from the patriotic tone of Aimé Champollion-Figeac’s Les Deux Champollion, published in 1887, with its remark that: ‘Today Champollion le jeune has entered posterity, the petty jealousies have fallen silent, Europe is unanimous in recognizing that his immortal discovery belongs to him in its entirety and not only to him, ultimately to France, which does not hesitate to count him among the innovative geniuses whose glory has made them fellow citizens of all peoples.’ Outside France, however, opinion has always been strongly divided. It is worth citing the opinions of three Egyptological experts to provide a flavour of the debate.

The Irishman Edward Hincks was a contemporary of Champollion and an early Egyptologist who later became a highly respected pioneer of the decipherment of Mesopotamian cuneiform. In 1846, Hincks wrote:

Had [Champollion] been candid enough to admit that he was indebted to Dr Young for the commencement of his discovery, and only to claim the merit of extending and improving [Young’s] alphabet, he would probably have had his claims to [his] subsequent discoveries, which were certainly his own, more readily admitted by Englishmen than they have been. In 1819 Dr Young had published his article ‘Egypt’ in the Supplement to the Encyclopaedia Britannica; and it cannot be doubted that the analysis of the names ‘Ptolemaeus’ and ‘Berenice’, which it contained, reached Champollion in the interval between his publications in 1821 and 1822, and led him to alter his views.

Half a century later, Egyptology had become an established academic discipline, with Champollion viewed as its ‘founding father’. Sir Peter le Page Renouf, a British Egyptologist (though partly of French ancestry) enraged by the continuing allegations that Champollion plagiarized Young, championed him with fierce conviction in 1896:

No one could learn anything from [Young’s] famous Essay [of 1819], for even the true things contained in it are logically undistinguishable [sic] from the false. Young was in the habit of calling Champollion’s discoveries an extension of his own. But the difference was not one of quantity but of quality. A man who sometimes hits upon the right answer to an arithmetical problem is not on the same level as one who knows the rule for working all such problems … Two undeniable facts remain after all that has been written: Champollion learnt nothing whatever from Young, nor did anyone else. It is only through Champollion and the method he employed that Egyptology has grown into the position which it now occupies.

At the beginning of the 21st century, a third Egyptologist, Richard Parkinson – the curator in charge of the Rosetta Stone at the British Museum – fell somewhere between the extremes of Hincks and Renouf. In 2005, he wrote: ‘Even if one allows that Champollion was more familiar with Young’s initial work than he subsequently claimed, he is the sole decipherer of the hieroglyphic script: any decipherment stands or falls as a whole, and while Young discovered parts of an alphabet – a key – Champollion unlocked an entire written language.’

Champollion himself was coy about when he first came to know of Young’s published contributions, and vague about what exactly he learnt from them.

In the Lettre à M. Dacier of 1822, he signally neglected Young, consigning him to one fairly long but uninformative footnote. Here, after accepting the correctness of a few of the signs in Young’s alphabetical reading of the Ptolemy and Berenice cartouches but criticizing other sign readings, Champollion grudgingly admitted:

M.le docteur Young has done in England, on the inscribed monuments of ancient Egypt, work analogous to that which has occupied me for so many years; and his researches on the intermediate text [i.e. demotic] and the hieroglyphic text of the inscription of Rosetta, as on the manuscripts that I have made known as ‘hieratic’, present a series of very important results. See the Supplement to the Encyclopaedia Britannica, vol. IV, pt. I, Edinburgh, December 1819.

But in the Précis du système hiéroglyphique des anciens Égyptiens of 1824, published after his dispute with Young came into the open, Champollion tellingly devoted virtually the entire first chapter of the book to an attempted refutation of Young’s claims. After listing six conclusions about Egyptian writing reached by Young from the beginning of his research until he published his article of 1819, Champollion baldly claimed, without specifying any dates: ‘I must say that in the same period, and without having any knowledge of the opinions of M. le docteur Young, I managed to arrive, by a fairly certain method, at more or less similar results.’ A few pages later, he noted that he had read Young’s Encyclopaedia Britannica article ‘in 1821’; in later life he stated that he read it ‘a little after my arrival in Paris, in September 1821’.

These claims, although defensible, are surely economical with the truth. As we know, it is certain that Champollion was aware of Young’s work in 1815, because the two of them corresponded after Champollion had written to the Royal Society in 1814. He almost certainly read Young’s ‘conjectural translation’ of the Rosetta Stone, in the copy lent by de Sacy to his brother at Champollion’s request in mid-1815. During late 1819 or 1820 (the date is uncertain), Champollion was informed of Young’s article in the Encyclopaedia Britannica by his brother and scoffed at some of its results. It is likely that he did not read the full article until after he reached Paris in the summer of 1821, because it was hard to obtain, even in England, according to independent witnesses. Notwithstanding, Young is known to have sent personal copies of the article to several scholars in 1819, including Edme Jomard and Alexander von Humboldt in Paris, so Champollion could have received a summary from his brother well before he arrived in Paris in July 1821. It strains credulity to suppose that the well-connected, highly determined Champollion-Figeac, private secretary to the permanent secretary of the Academy of Ancient Inscriptions, could not have procured a copy of Young’s article in Paris in 1819–20.

Whatever the true extent of Champollion’s knowledge of Young’s work in 1815–21, in the introduction to his Précis he felt obliged to concede the following achievements to Young:

I … recognize that he was the first to publish some correct ideas about the ancient writings of Egypt; that he also was the first to establish some correct distinctions concerning the general nature of these writings, by determining, through a substantial comparison of texts, the value of several groups of characters. I even recognize that he published before me his ideas on the possibility of the existence of several sound-signs, which would have been used to write foreign proper names in Egypt in hieroglyphs; finally that M. Young was also the first to try, but without complete success, to give a phonetic value to the hieroglyphs making up the two names Ptolemy and Berenice.

In my view, unprovable as it may be, this statement was a tacit admission that it was Young’s 1819 article that compelled Champollion to embrace the existence of a phonetic component in the Egyptian scripts. Since 1810, Champollion had oscillated in his view of hieroglyphic, hieratic and demotic phoneticism; now Young’s analysis and results were too decisive to ignore. Phoneticism had to be present in the signs within the cartouches that spelt foreign proper names, at the very least. The plate section of Young’s article saliently published what he called ‘something like a hieroglyphic alphabet’ in the form of a list of fourteen hieroglyphs labelled ‘Sounds?’, along with a second, longer list of demotic signs labelled ‘Supposed enchorial alphabet’, modified from those suggested by Åkerblad. As he explained in his accompanying text, Young had derived this rudimentary hieroglyphic alphabet from the cartouches of Ptolemy and Berenice, by attempting to match each hieroglyphic sign in a cartouche with its apparently equivalent alphabetic letter in the names’ Greek spelling. Although some of the phonetic values he assigned were incorrect, the ‘matching’ principle was convincing. Surely, having critically digested Young’s articles and accepted both this principle and some of Young’s results, however reluctantly, Champollion was now primed to take his own first correct, original step.

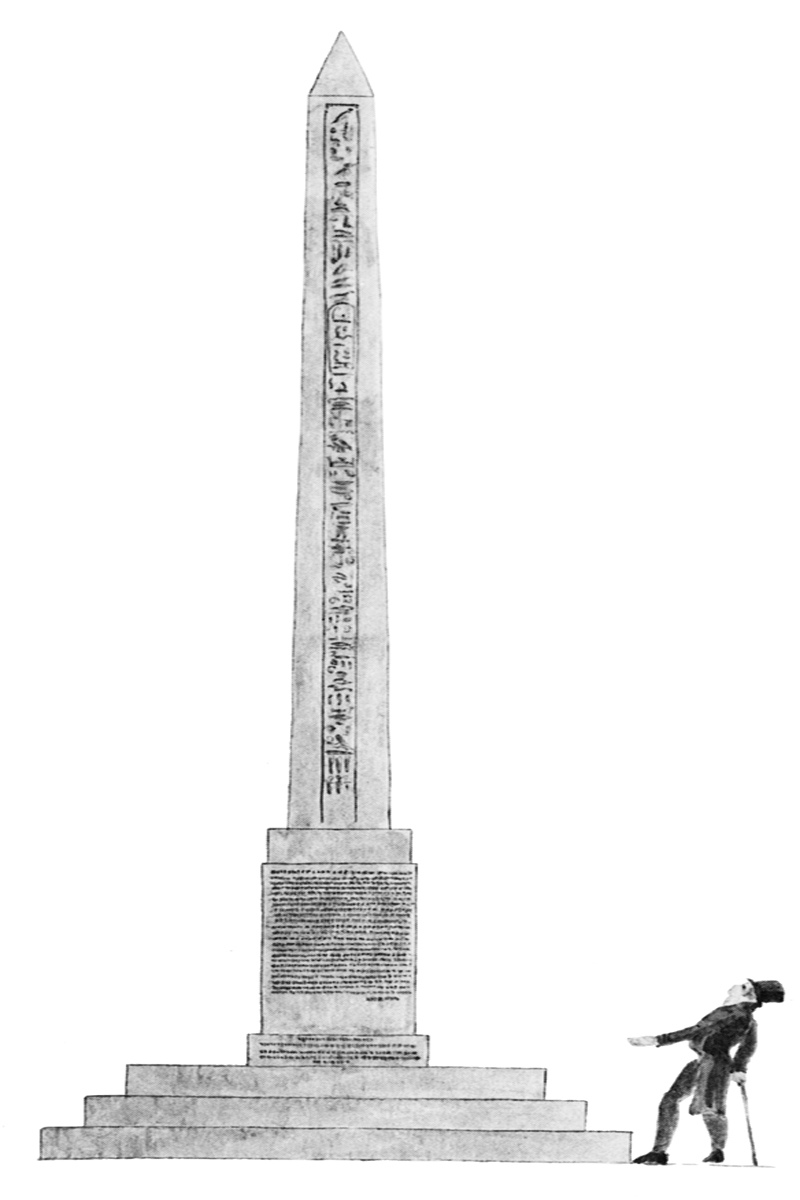

The moment came in January 1822, when Champollion saw a copy of an obelisk inscription sent to the French Institute by an English traveller and collector, William Bankes, who was a friend of Young. Bankes had had the obelisk removed from the island of Philae (near Aswan) by Belzoni in 1818 for transportation to London, where it finally arrived by ship in September 1821, though without its base block, which had been accidentally stranded in a cataract of the Nile. Its inscriptions (including those on the base block) were copied in London and published in November 1821 by Bankes, who sent the published drawings to interested individuals and institutions. The object itself – the first ancient Egyptian obelisk to reach Britain – was eventually erected at Bankes’s country house at Kingston Lacy in Dorset, where it still stands.

Drawing of the Bankes obelisk from Philae, made in 1821 in preparation for its publication. The obelisk stands in Kingston Lacy, Dorset, in the grounds of the former house of William Bankes.

(Bankes Collection, Kingston Lacy, Dorset.)

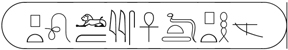

The Bankes obelisk is important to the story of decipherment because it bore two languages. The inscription on the base block was in Greek, while that on the column was in hieroglyphic script. This, however, did not make it a true bilingual inscription, a second Rosetta Stone, because the two inscriptions did not match. Notwithstanding, in 1818 Bankes realized that in the Greek letters the names of Ptolemy and Cleopatra, Ptolemaic queen, were mentioned, while in the hieroglyphs two (and only two) cartouches occurred – presumably representing the same two names that were written in Greek on the base. One of these cartouches was almost the same as a long cartouche on the Rosetta Stone identified by Young as representing Ptolemy plus a title:

Rosetta Stone

Philae obelisk

– so the second cartouche on the obelisk was likely to read ‘Cleopatra’. In sending the drawing of the Philae inscription to Young and other scholars – including Denon, who presented his copy to the French Institute – Bankes pencilled his proposed identification of Cleopatra in the margin of the copy.

Unfortunately for Young, the copy contained a significant error. The copyist had expressed the first letter of Cleopatra’s name using the sign for t ( ) instead of k (

) instead of k ( ). Later, Young noted that ‘as I had not leisure at the time to enter into a very minute comparison of the name with other authorities, I suffered myself to be discouraged with respect to the application of my alphabet to its analysis’. In other words, Young was unlucky here; but he was also undermined by his lifelong polymathic tendency to spread himself too thinly. Not long before this, he had been appointed as the superintendent of the Board of Longitude’s Nautical Almanac, a demanding position that took him away from Egyptian studies.

). Later, Young noted that ‘as I had not leisure at the time to enter into a very minute comparison of the name with other authorities, I suffered myself to be discouraged with respect to the application of my alphabet to its analysis’. In other words, Young was unlucky here; but he was also undermined by his lifelong polymathic tendency to spread himself too thinly. Not long before this, he had been appointed as the superintendent of the Board of Longitude’s Nautical Almanac, a demanding position that took him away from Egyptian studies.

Champollion, after a decade and a half of effort and frustration, was not about to be diverted from his study of Egypt by other interests and duties, or by a copyist’s error. During 1821, he had ascertained the demotic spelling of Cleopatra from a bilingual Greek–demotic papyrus recently collected in Egypt by an Italian, Casati, as noted in his Lettre à M. Dacier. According to Hartleben, this demotic spelling allowed Champollion to construct a hypothetical hieroglyphic spelling of the queen’s name from his knowledge of demotic–hieroglyphic sign equivalences. But this claim has seemed implausible to modern Egyptologists (Henri Sottas, for example, in his detailed analysis of the Lettre), nor was the claim actually maintained by Champollion himself. More likely is that he identified four similar-looking cartouches published in the Description de l’Égypte between 1809 and 1817, each containing the feminine termination and the signs from ‘Cleopatra’ if the name was indeed spelt phonetically – in particular the signs standing for l, o and p, which were known from the cartouche for Ptolemy (as shown by Young). However, Champollion did not claim that this was his method, either. Most likely is that he simply took the pencilled clue offered by Bankes and hazarded some guesses about the phonetic values of Bankes’s cartouche. But if this really was what he did, he did not confess it and made no acknowledgment. (An offended Bankes thereafter refused to give Champollion any help, despite his requests.)

‘Cleopatra’, a research note in Champollion’s manuscripts on the vital cartouche from the obelisk that Bankes acquired from Philae.

(Cleopatra cartouche, drawing from Champollion’s notebook. Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris.)

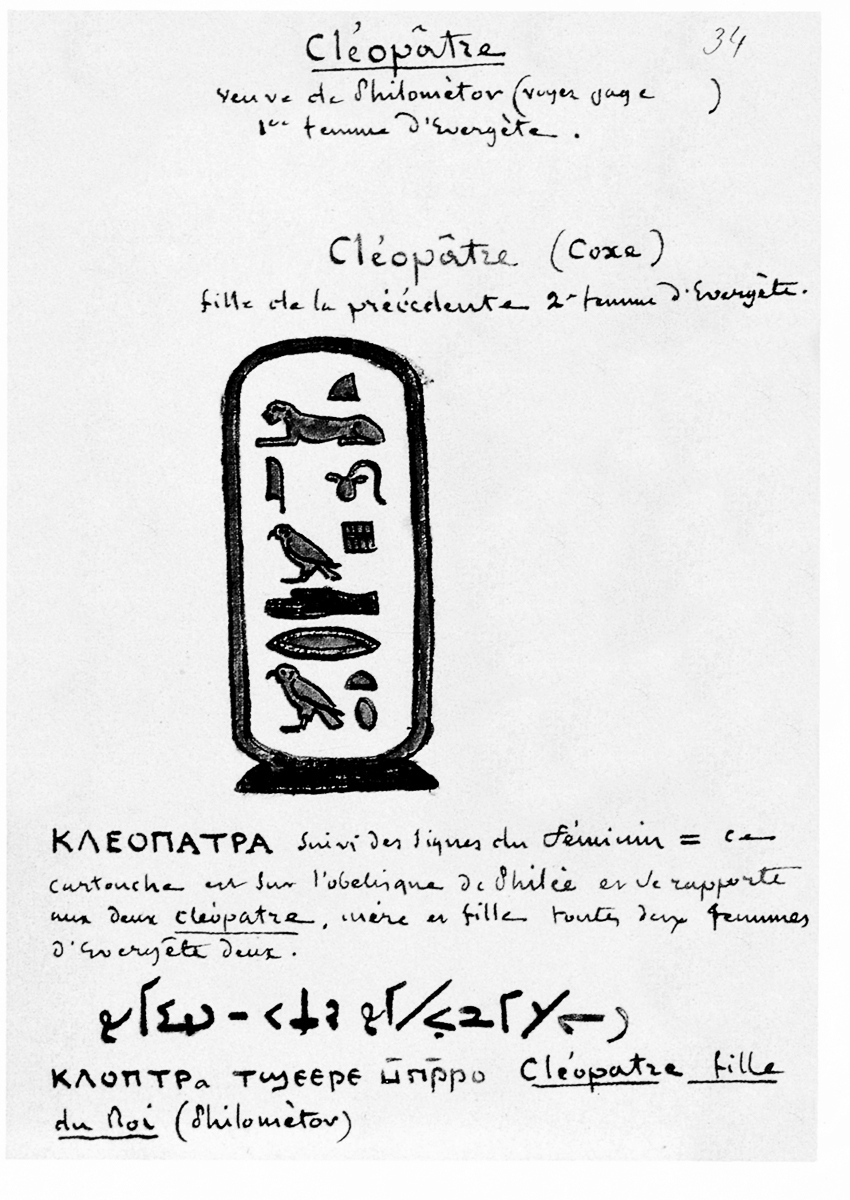

Whatever route Champollion may have followed to identify the cartouche, Cleopatra’s name proved to be his key to the phonetic system. Just as Young had done, Champollion decided that the shorter of the two versions of the Ptolemy cartouche on the Rosetta Stone spelt only Ptolemy’s name, while a second, longer cartouche must have involved some royal title tacked onto Ptolemy’s name. Again like Young, Champollion assumed that Ptolemy was spelt alphabetically, and thus, following Bankes’s identification, that the same principle must apply in the spelling of Cleopatra on the obelisk from Philae. He proceeded to guess the phonetic values of the hieroglyphs in both cartouches:

There were four signs in common – those with the phonetic values l, e, o and p – but the phonetic value t was represented differently in the two names. Champollion deduced correctly that the two signs for t were what are known as ‘homophones’, that is, different signs with the same sound (compare, in English, Jill and Gill, Catherine and Katherine) – a concept of which Young was also aware. The real test of the decipherment, however, was whether these new phonetic values, when applied to the cartouches in other inscriptions, would produce sensible names. Champollion tried them in the following cartouche:

Substitution produced Al?se?tr?. Champollion guessed the name Alksentrs, equating to the Greek Alexandros (Alexander): the two signs for k/c ( and

and  ) are almost homophonous, as are the two different signs for s (

) are almost homophonous, as are the two different signs for s ( and

and  ). Using his growing alphabet, Champollion went on to identify the cartouches of other rulers of non-Egyptian origin, such as Berenice (already tackled by Young, though with mistakes) and Roman emperors such as Trajan, including their titles of Caesar and Autocrator (which Young had mistakenly identified as Arsinoe).

). Using his growing alphabet, Champollion went on to identify the cartouches of other rulers of non-Egyptian origin, such as Berenice (already tackled by Young, though with mistakes) and Roman emperors such as Trajan, including their titles of Caesar and Autocrator (which Young had mistakenly identified as Arsinoe).

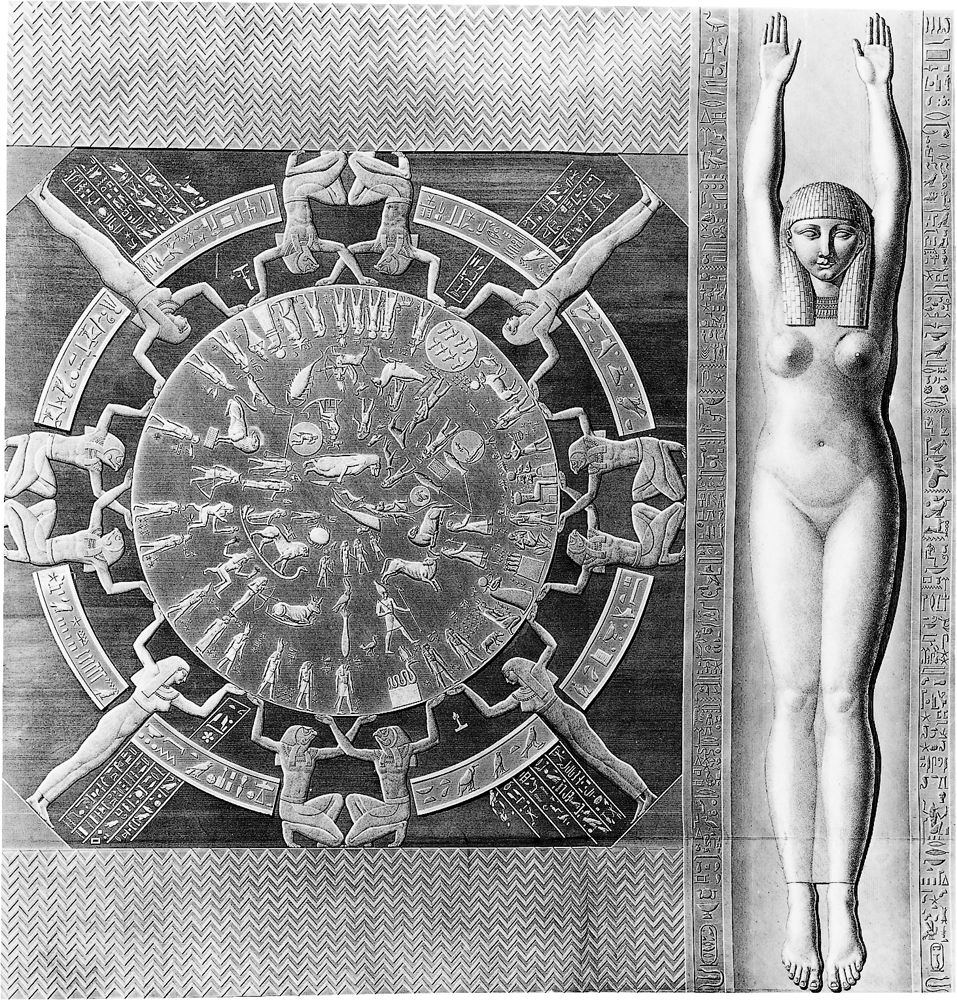

The last identification, Autocrator, would attract unexpected attention during 1822. The cartouche in question came from a drawing in the Description de l’Égypte of an important temple at Dendera, not far north of Thebes. The temple’s ceiling was carved with a controversial inscription, the Dendera Zodiac, which had been discovered and drawn by Napoleon’s savants. Two decades later, in 1821, an enterprising if unscrupulous French engineer had partially sawn the zodiac off the temple ceiling and shipped it to Paris, where it went on public display. In 1822, the Dendera Zodiac was more celebrated in the French capital than the Rosetta Stone. There was even a vaudeville theatre production, Le Zodiaque de Paris, with actors playing each sign of the zodiac and a chorus of wailing mummies, which satirized the popular, official and scholarly reactions to the exotic antique, despite heavy government censorship.

Drawing of the Dendera Zodiac and its surrounding hieroglyphs, published in the Description de l’Égypte. The cartouche immediately to the left of the feet of the full-length figure, which apparently reads ‘Autocrator’, turned out to be a copyist’s error (see page 203).

(Dendera Zodiac, drawing from Description de l’Égypte, Paris, 1823.)

The reason for the furore was that the zodiac had come to stand for a clash between science and religion. Almost from the moment of its discovery in Egypt in the late 1790s, the zodiac’s date of origin had been hotly contested. According to some astronomical analysis of the historical star positions supposedly depicted in the zodiac, the object, and therefore Egyptian civilization, seemed to be older than permitted by the biblical account of the creation of man – as much as 15,000 years older than Christ, according to an initial estimate by Fourier in 1802. But according to other astronomical analysis, such as that by the physicist Jean-Baptiste Biot, the zodiac dated from much later: the positions of its stars represented the state of the heavens in about 747 BC. This was the view supported by the Catholic Church, needless to say. For more than two decades, the Dendera Zodiac was a cause célèbre for left-wing atheists and the right-wing devout.

In the end, the Gordian knot was cut not by the quarrelling scientists and priests, but by Champollion. From his study of ancient Egyptian religion, Champollion grasped that the Dendera Zodiac was of astrological, not astronomical, significance. Its age, therefore, could not be calculated from its star positions; rather, it could be dated from its hieroglyphic inscriptions. When he read the cartouche from the Dendera temple as a Roman title, Autocrator, a late date for the zodiac seemed assured. (The date given by modern scholars is the 1st century BC, the time of Cleopatra, who is depicted in the temple.) Champollion, despite his belief in the great antiquity of Egyptian civilization and his dislike of the conservative éteignoirs, now found himself promoted by the Catholic Church as a saviour of the true Christian faith, whether he liked it or not.

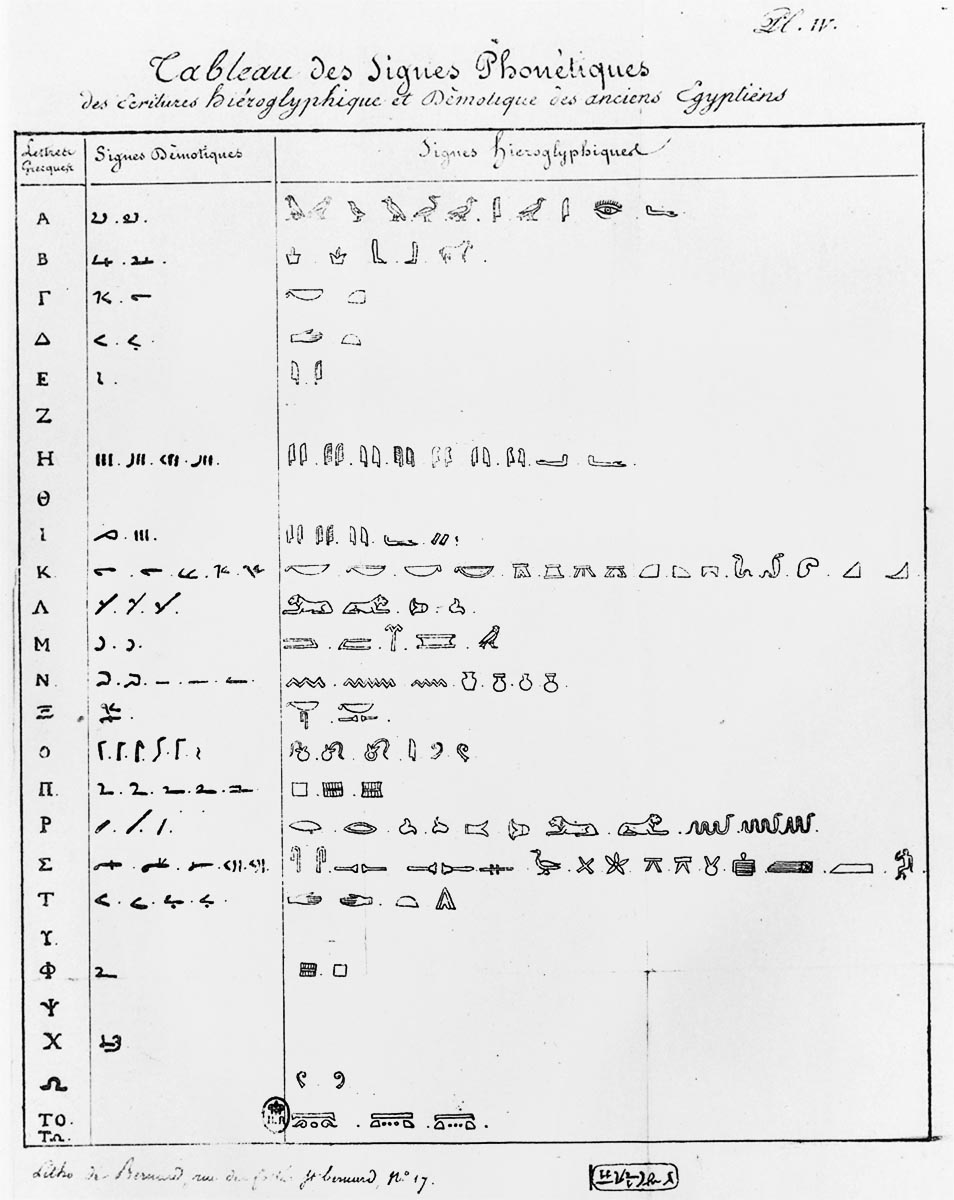

Champollion reached his conclusion about this cartouche in the summer of 1822. By now, it was clear to him that the hieroglyphic code was beginning to break. The decipherment of one cartouche had led to the decipherment of another, and another, and yet another. From many such Greco-Roman proper names and titles written in hieroglyphs, Champollion worked out a table of phonetic signs, in the manner of Young’s ‘hieroglyphic alphabet’, but much fuller than his rival’s and more accurate (though still with plenty of errors). He would soon publish his findings in the Lettre à M. Dacier.

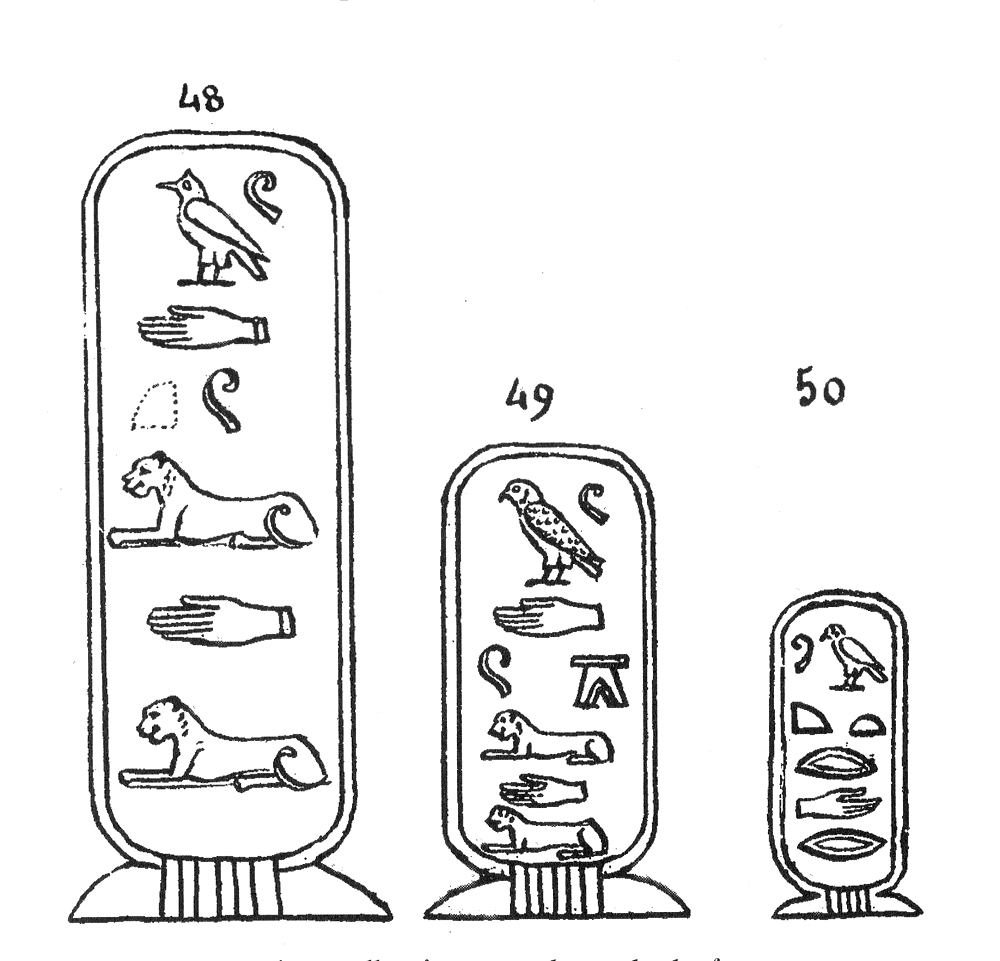

Three variant hieroglyphic cartouches of the title Autocrator, drawn by Champollion and published in the Lettre à M. Dacier.

(‘Autocrator’ cartouche, drawings by Champollion. Photo Andrew Robinson.)

However, at this juncture – the first phase of the decipherment – Champollion did not expect his phonetic values to apply to the names of native Egyptian rulers, which he persisted in thinking would be spelt non-phonetically. Even less did he expect that his values would apply to the entire Egyptian writing system.

It was a hieroglyphic inscription he received on the morning of 14 September 1822 that launched the second phase of his decipherment. Drawn by a French architect, Jean-Nicolas Huyot, who had recently travelled in Egypt with Bankes, the inscription came from the great temple of Abu Simbel in Nubia and contained intriguing cartouches. They appeared to write the same name in a variety of ways, the simplest being:

The last two signs were familiar to Champollion as having the phonetic value s. Using his knowledge of Coptic, he guessed that the first sign had the value re, which was the Coptic word for ‘sun’ – the object that the sign apparently symbolized. (Or perhaps he simply followed Young, who had made the connection clear in his 1819 article.) Did an ancient Egyptian pharaoh with a name that resembled R(e)?ss exist? Champollion, steeped in his knowledge of ancient Egypt, thought of Ramesses, a king of the 19th dynasty mentioned in a well-known Greek history of Egypt written in the 3rd century BC by a Ptolemaic historian, Manetho. (Even current Egyptologists use Manetho’s text as the basic framework of ancient Egyptian history.) If this speculation was correct, then the sign  must have the phonetic value m. (Champollion believed that the hieroglyphic script did not represent vowels, except in the case of foreign proper names such as Cleopatra.)

must have the phonetic value m. (Champollion believed that the hieroglyphic script did not represent vowels, except in the case of foreign proper names such as Cleopatra.)

Encouragement came from a second hieroglyphic inscription:

Two of these signs were ‘known’; the first, an ibis, was a symbol of the god Thoth (the inventor of writing). The name, then, had to be Thothmes/Thuthmosis, a pharaoh of the 18th dynasty also mentioned by Manetho. (Young had already identified this cartouche as belonging to Thuthmosis, but he had not attempted to read the signs phonetically.) The Rosetta Stone appeared to confirm the value of  . The sign occurred there, again with

. The sign occurred there, again with  , as part of a group of hieroglyphs with the Greek translation ‘genethlia’, meaning ‘birthday’. Champollion was at once reminded of the Coptic for ‘give birth’, ‘mise’. (He was only half right about the spelling of Ramesses:

, as part of a group of hieroglyphs with the Greek translation ‘genethlia’, meaning ‘birthday’. Champollion was at once reminded of the Coptic for ‘give birth’, ‘mise’. (He was only half right about the spelling of Ramesses:  does not have the phonetic value m, as he thought, but rather the biconsonantal value ms, as implied by the Coptic ‘mise’. Champollion was as yet unaware of this complexity.)

does not have the phonetic value m, as he thought, but rather the biconsonantal value ms, as implied by the Coptic ‘mise’. Champollion was as yet unaware of this complexity.)

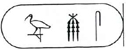

Six variant hieroglyphic cartouches of the name Ramesses II, drawn by Champollion and published in the Précis du système hiéroglyphique des anciens Égyptiens.

(Six cartouches of Ramesses II from Champollion’s Précis du système hiéroglyphique des anciens Égyptiens, 1828.)

Once he had accepted that the hieroglyphs were a mixture of phonetic signs and signs standing for whole words, Champollion could decipher the second half of the long cartouche belonging to Ptolemy – i.e. the king’s title – on the Rosetta Stone. That is:

According to the Greek inscription, the entire cartouche meant ‘Ptolemy living for ever, beloved of Ptah’. Ptah was the creator god of the city of Memphis. In Coptic, the word for ‘life’ or ‘living’ was ‘onkh’; this was thought to be derived from the ancient Egyptian word ‘ankh’, represented by the sign  (a whole-word sign). Presumably the next signs

(a whole-word sign). Presumably the next signs  meant ‘ever’ and contained a t sound, given that the sign

meant ‘ever’ and contained a t sound, given that the sign  was now known to have the phonetic value t. With help from Greek and Coptic, the

was now known to have the phonetic value t. With help from Greek and Coptic, the  could be assigned the phonetic value dj, giving a rough ancient Egyptian pronunciation djet, meaning ‘for ever’. (The other sign

could be assigned the phonetic value dj, giving a rough ancient Egyptian pronunciation djet, meaning ‘for ever’. (The other sign  was silent, a kind of classificatory word sign now known as a determinative; it symbolized ‘flat land’.)

was silent, a kind of classificatory word sign now known as a determinative; it symbolized ‘flat land’.)

Of the remaining signs,  , the first was now known to stand for p and the second for t – the first two sounds of Ptah; and so the third sign could be given the approximate phonetic value h. The fourth sign – another whole-word sign – was therefore assumed to mean ‘beloved’. Coptic once more came in useful in assigning a pronunciation: the Coptic word for ‘love’ was known to be ‘mere’, and so the pronunciation of the fourth sign was thought to be mer. In sum, Champollion arrived at the following rough approximation of the famous Rosetta Stone cartouche (guessing at the unwritten vowels): Ptolmes ankh djet Ptah mer – ‘Ptolemy living for ever, beloved of Ptah’.

, the first was now known to stand for p and the second for t – the first two sounds of Ptah; and so the third sign could be given the approximate phonetic value h. The fourth sign – another whole-word sign – was therefore assumed to mean ‘beloved’. Coptic once more came in useful in assigning a pronunciation: the Coptic word for ‘love’ was known to be ‘mere’, and so the pronunciation of the fourth sign was thought to be mer. In sum, Champollion arrived at the following rough approximation of the famous Rosetta Stone cartouche (guessing at the unwritten vowels): Ptolmes ankh djet Ptah mer – ‘Ptolemy living for ever, beloved of Ptah’.

The events that followed these few hours of logic, intuition and luck are truly worthy of the Romantic movement, the age of Byron and Goethe. It was said in the Champollion family – as Aimé Champollion-Figeac recorded long after the death of his uncle – that towards noon on 14 September 1822 Jean-François rushed from his house in the Rue Mazarine to the nearby Academy of Inscriptions and Belles-Lettres, flung a bundle of drawings of Egyptian inscriptions onto a desk in Jacques-Joseph’s office, and cried: ‘Je tiens mon affaire!’ (‘I’ve done it!’) – his own version of Archimedes’s cry ‘Eureka!’. But before he could explain what he had done, he collapsed on the floor in a dead faint. For an instant, his brother feared that he was dead. Taken home to rest, Champollion apparently did not revive until eveningtime five days later, when he immediately plunged into work again. On 27 September, he gave his celebrated lecture at the Academy of Inscriptions and Belles-Lettres announcing his breakthrough, which was published in October as the Lettre à M. Dacier, relative à l’alphabet des hiéroglyphes phonétiques. The surviving manuscript shows that the letter was originally to have been addressed to de Sacy; this name has been crossed out by Champollion-Figeac and replaced with the name of the faithful Dacier.

By an extraordinary fluke of history, Young happened to be in Paris in late September 1822, accompanying his wife on a foreign visit, and he was present at Champollion’s lecture on 27 September. In fact, he was invited to sit next to his rival while Champollion read out his paper. It was the first personal encounter between the two decipherers, who were formally introduced after the meeting by a mutual friend, the physicist François Arago. Although there is no direct report of their conversation, it appears to have been amicable, judging from their significant correspondence during the next three or four months, in which Champollion sent Young details of some of his latest results.

Nonetheless, during the Paris lecture Young could hardly have avoided noticing Champollion’s lack of open acknowledgment of his own work. He wrote to his friend Hudson Gurney from Paris:

Fresnel, a young mathematician of the Civil Engineers, has really been doing some good things in the extension and application of my theory of light, and Champollion … has been working still harder upon the Egyptian characters. He devotes his whole time to the pursuit and he has been wonderfully successful in some of the documents that he has obtained – but he appears to me to go too fast – and he makes up his mind in many cases where I should think it safer to doubt. But it is better to do too much than to do nothing at all, and others may separate the wheat from the chaff when his harvest is complete. How far he will acknowledge everything which he has either borrowed or might have borrowed from me I am not quite confident, but the world will be sure to remark que c’est le premier pas qui coûte [‘it’s the first step that costs’] though the proverb is less true in this case than in most, for here every step is laborious. I have many things I should like to show Champollion in England, but I fear his means of locomotion are extremely limited, and I have no chance of being able to augment them.

Title page of the Lettre à M. Dacier, published by Champollion in 1822

(Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris.)

Young’s work was conspicuously downplayed in the Lettre à M. Dacier – so patently, in fact, that anyone knowledgeable about the recent history of the Rosetta Stone could not fail to conclude that Champollion had done so deliberately. As Young would remark publicly in 1823, with notable understatement: ‘I did certainly expect to find the chronology of my own researches a little more distinctly stated.’ Champollion’s first publication of the decipherment in October 1822 shows that from the very beginning he was set on keeping all the glory for himself, since he could have had no other motive to downplay Young’s role at this time, before Young had made a single public criticism of him or his work.

Champollion’s attitude to Young is most evident if we consider Champollion’s description of how he identified Cleopatra’s cartouche and used it, with Ptolemy’s cartouche, to construct an alphabet. The following account is Young’s own translation from Champollion’s Lettre (the emphases are also Young’s):

The hieroglyphical text of the inscription of Rosetta exhibited, on account of its fractures, only the name of Ptolemy. The obelisk found in the Isle of Philae, and lately removed to London, contains also the hieroglyphical name of one of the Ptolemies, expressed by the same characters that occur in the inscription of Rosetta, surrounded by a ring or border [i.e. a cartouche], and it is followed by a second border, which must necessarily contain the proper name of a woman, and of a queen of the family of the Lagidae, since this group was terminated by the hieroglyphics expressive of the feminine gender; characters which are found at the end of the names of all the Egyptian goddesses without exception. The obelisk was fixed, it is said, to a basis bearing a Greek inscription, which is a petition of the priests of Isis at Philae, addressed to King Ptolemy, to Cleopatra his sister, and to Cleopatra his wife. Now, if this obelisk, and the hieroglyphical inscription engraved on it, were the result of this petition, which in fact adverts to the consecration of a monument of the kind, the border, with the feminine proper name, can only be that of one of the Cleopatras. This name, and that of Ptolemy, which in the Greek have several letters in common, were capable of being employed for a comparison of the hieroglyphical characters composing them; and if the similar characters in these names expressed in both the same sounds, it followed that their nature must be entirely phonetic.

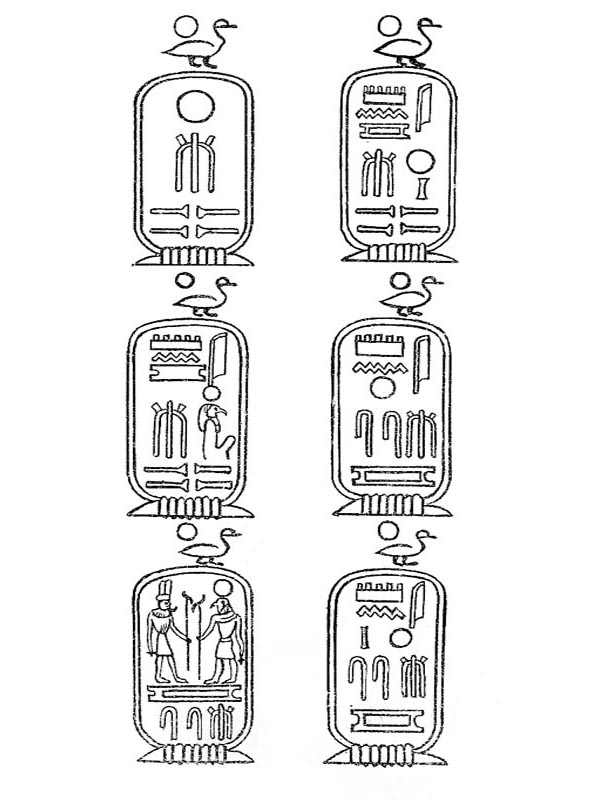

‘Table des Signes Phonétiques’ from the Lettre à M. Dacier. This table of demotic and hieroglyphic signs with their Greek equivalents – a hieroglyphic ‘alpabet’ – was drawn up by Champollion in October 1822. His own name appears in demotic script at the bottom, enclosed in a cartouche.

(‘Table des Signes Phonétiques‘, from the Lettre à M. Dacier, 1822. Facsimile in Académie des Inscriptions, vol. 25, 1921–22.)

There was not even a nod to Young (or Bankes). The omission stung him, and, with the encouragement of his friend Gurney, spurred him into publishing a book in April 1823 for a general readership, this time under his own name, entitled An Account of Some Recent Discoveries in Hieroglyphical Literature and Egyptian Antiquities. Here Young commented on the previous passage by Champollion as follows:

This course of investigation appears, indeed, to be so simple and so natural, that the reader must naturally be inclined to forget that any preliminary steps were required: and to take it for granted, either that it had long been known and admitted, that the rings on the pillar of Rosetta contained the name of Ptolemy, and that the semicircle and the oval constituted the female termination, or that Mr Champollion himself had been the author of these discoveries.

It had, however, been one of the greatest difficulties attending the translation of the hieroglyphics of Rosetta, to explain how the groups within the rings, which varied considerably in different parts of the pillar, and which occurred in several places where there was no corresponding name in the Greek, while they were not to be found in others where they ought to have appeared, could possibly represent the name of Ptolemy; and it was not without considerable labour that I had been able to overcome this difficulty. The interpretation of the female termination had never, I believe, been suspected by any but myself: nor had the name of a single god or goddess, out of more than 500 that I have collected, been clearly pointed out by any person.

But, however Mr Champollion may have arrived at his conclusions, I admit them, with the greatest pleasure and gratitude, not by any means as superseding my system, but as fully confirming and extending it.

Indeed, Young added a provocative subtitle to his book: Including the Author’s Original Alphabet, As Extended by Mr Champollion.

Champollion was duly provoked. On 23 March 1823, having seen only an advertisement for Young’s new book, he wrote angrily to him: ‘I shall never consent to recognize any other original alphabet than my own, where it is a matter of the hieroglyphic alphabet properly called; and the unanimous opinion of scholars on this point will be more and more confirmed by the public examination of any other claim.’ Scholarly war had been declared.

Young’s supporters felt that he had taken the vital first steps that had enabled Champollion to advance, and that Champollion had either ignored them or claimed that he had come to the same conclusions independently. ‘Nothing can exceed the effrontery of Champollion in thus complaining to Dr Young, the author of the discoveries … as if he himself were the person aggrieved,’ wrote John Leitch, the editor of Young’s Egyptological works. Champollion’s supporters argued, by and large, that while Young had taken some first steps, not all of them were correct, as witness his misreading of some of the signs in the cartouches of Ptolemy and Berenice. Champollion, they said, had established a system that worked easily when applied to new cartouches, as opposed to Young’s more ad hoc methods, which in some cases required ingenious manipulation to produce phonetic values. And inevitably they pointed to Champollion’s truly revolutionary progress from 1823 onwards, which Young himself generally admired.

At the end of the chapter in his book named ‘Mr Champollion’, Young summarized his basic wish about his French rival:

[that] the further he advances by the exertion of his own talents and ingenuity, the more easily he will be able to admit, without any exorbitant sacrifice of his fame, the claim that I have advanced to a priority with respect to the first elements of all his researches; and I cannot help thinking that he will ultimately feel it most for his own substantial honour and reputation, to be more anxious to admit the just claims of others than they be to advance them.

This was a reasonable, temperate suggestion, given the pioneering role Young had played in 1814–19, but it fell on stony ground. Champollion’s rejection of it was virtually inevitable. For him to have agreed to Young’s request would have made a mockery of his long years of obsession with ancient Egypt, beginning with his time as an impecunious student in Paris in 1807, for which he had truly suffered – unlike the comfortably-off Young. Or perhaps Champollion had convinced himself that he had genuinely taken the inaugural steps in the first phase of the decipherment, whether independently of Young or by correcting him. In all probability both thoughts coexisted in his mind. There was, in addition, the fact that his rival was an Englishman – Champollion’s least-favoured nationality – and thus a representative of the nation that had taken the Rosetta Stone from its French discoverers. To cap it all, Champollion was always a man attracted to extremes, unlike the moderate Young. In his by no means entirely convincing proof in the Précis of Young’s lack of system, Champollion dramatically concluded that Young’s system applied ‘to nothing’, whereas his own system applied ‘to all’ (the italics are Champollion’s). But of course this all-or-nothing distinction, even supposing it were true of Champollion’s system (which it was not, as of 1824), implied nothing definite about its origins, despite Champollion’s indignant insistence to the contrary.

Nevertheless, by sticking intransigently to his claim of sole authorship, Champollion would achieve his ambition and come to enjoy wide acceptance in his lifetime as the decipherer of the Egyptian hieroglyphs. But in so doing he would lose his good name, rather like Isaac Newton in physics, who denied any credit to other scientists such as Robert Hooke. Young was right in his moderate warning: Champollion’s personal reputation would forever be tainted by his hubris towards Young. An English friend and admirer of both men, the antiquarian Sir William Gell, who had studied their work in detail as it developed, commented aptly of Champollion to Young in 1828: ‘I wish he would have the decency to write you a letter in print and confess your originality and his own embryo ideas emanating from your discoveries, without which his real merits seem to me always in a cloud.’

By the time Young’s book appeared in April 1823, Champollion was already far ahead of him. He was about to embark on the third phase of the decipherment as explained above, which would lead to the publication of his magnificent Précis du système hiéroglyphique des anciens Égyptiens in 1824. Even in the closing pages of the Lettre à M. Dacier, he had hinted at the existence of a single, universally valid hieroglyphic system, by hazarding that ‘the phonetic writing existed in Egypt in the far distant past’, long before the arrival of the Greeks. Young, in his book, was cautiously sceptical of this claim, even where it concerned the names of the ancient pharaohs, let alone the rest of the hieroglyphs.

What exactly happened to reorient Champollion’s mind in the six months or so between the Lettre of September 1822 and his next key announcement to the Academy of Inscriptions in April 1823? He gave no direct explanation in his Précis. Hartleben maintained that the idea of the hieroglyphic system as a mixture of phonetic, figurative and symbolic signs came to Champollion in December 1821 – on his birthday, 23 December, according to an established ‘tradition’ mentioned by Hartleben in a footnote to her original German biography (which is omitted from the French translation). But this date, 23 December 1821, is unquestionably wrong – too early – because we know that Champollion firmly dismissed phoneticism in the hieroglyphs (except for the cartouches) as late as the Lettre à M. Dacier in September 1822. A far more likely date, if we choose to stick with the birthday story, would be a year later: 23 December 1822. By then, an excited Champollion had transliterated the cartouches of some thirty more pharaohs (as he would inform Young in early January 1823) and was surely having serious doubts about whether his theory of ‘things not sounds’ was valid for the rest of the hieroglyphs. In other words, by December 1822 the evidence against his theory had reached a ‘critical mass’ in Champollion’s mind, leading to an efflorescence of insights.

Probably a combination of several factors was in play. For one thing, at this time Champollion learnt with surprise from a newly published French grammar of Chinese that there were phonetic elements not only in foreign proper names written in Chinese characters, but also in native Chinese words. If so in Chinese, why not also in Egyptian? For another, he tried counting the characters on the Rosetta Stone, as Hartleben mentions. This is how Champollion explained his analysis in the Précis:

The 14 partially damaged [hieroglyphic] lines of which it is composed correspond more or less to 18 complete lines in the Greek text, which, at 27 words per line [the average number over 10 lines] would form 486 words; and the ideas expressed in these 486 Greek words are expressed, in the hieroglyphic text, by 1,419 signs; and among this great number of signs, there are only 166 signs of different form … This calculation therefore establishes that the number of hieroglyphic signs is not nearly as extensive as is generally supposed; and it seems to prove above all … that each hieroglyph does not express on its own an idea, since 1,419 hieroglyphic signs are needed to represent only 486 Greek words, or alternatively 486 Greek words are enough to express the ideas noted by 1,419 hieroglyphic signs.

So 1,419 hieroglyphs corresponded to 486 Greek words; and among these 1,419 hieroglyphs there were only 166 individual signs. If each hieroglyph truly represented an idea or word, then one would have expected similar numbers of hieroglyphs and Greek words, and a larger set of separate signs, each one representing a different idea or word. All of a sudden, it must have struck Champollion that the hieroglyphs on the Rosetta Stone could be explained not by a purely ‘ideographic’ system, but by a small set of frequently employed phonetic hieroglyphs – an alphabet like the one he had published in 1822 – mixed with many more non-phonetic hieroglyphs that stood only for ideas or words.

A few weeks after this revelation, Champollion had a second life-changing experience of a completely different kind. ‘The publication of his letter to Dacier had brought him not the least advantage,’ noted Hartleben: ‘pointless admiration on the one side, jealousy and scepticism on the other.’ Champollion needed practical help with his research. In January 1823, he visited a saleroom in Paris in order to copy a text from an Egyptian collection that had come up for auction. He began quickly and surely to sketch the Egyptian inscriptions in his notebook. An older man, watching him at work, engaged him in conversation. Soon, Champollion found himself discussing without reserve the importance of a recent Egyptian collection sold by the French consul-general in Egypt, Bernardino Drovetti, to the king of Sardinia for display in his royal museum in Turin. What a scandal, said Champollion, that these treasures had not been acquired by the French government!

The stranger was none other than the duke of Blacas d’Aulps, one of the most influential and loyal courtiers of the king of France, who had spent many years as French ambassador in Naples and later in Rome, where he built up an art collection that would eventually became part of today’s British Museum. Despite their exceptionally different backgrounds and political views, Blacas was drawn to Champollion by a shared passion for ancient Egypt. Perhaps, too, as the first provincial noble to obtain high office in Louis XVIII’s court, Blacas felt sympathy for a fellow man from the provinces with high ambitions of a different kind. Both Champollion and Blacas were somewhat arrogant, and outsiders to the Establishment, with numerous detractors. Theirs seems an unlikely partnership, but it would certainly work to the advantage of both Champollion and the French government during the 1820s.

Blacas became Champollion’s second mentor after Champollion-Figeac, generously supporting his research and protecting him from enemies. In February 1823, he presented his protégé with a gold box from the king, inscribed as follows: ‘King Louis XVIII to M. Champollion le Jeune on the occasion of his discovery of the alphabet of the hieroglyphs’. In early 1824, Blacas arranged for Champollion’s forthcoming Précis to be dedicated to the king and organized a personal meeting between the decipherer and the monarch. Thanks to Blacas, Champollion would receive the financial help he needed to take him on the next step of his voyage towards Egypt: a study tour of the ancient Egyptian treasures gathered in Italy since the days of ancient Rome.

Portrait of the duke of Blacas d’Aulps, friend of Louis XVIII and Charles X, and mentor and benefactor of Champollion.

(Photo Domergue.)