The dog in Egypt lives in a state of complete liberty, and in going to the obelisks we were accompanied by the barking of a crowd of these animals, which occupied the summits of the dunes one by one as they pursued us at quite a distance with husky, muffled cries. These dogs, though of varying sizes, are of one and the same species; they strongly resemble the jackal, except for their coats, which are yellow-red. I am no longer astonished that in the hieroglyphic inscriptions it should be so difficult to distinguish the dog from the jackal: their defining characteristics are identical. The hieroglyphic dog differs only in having a tail raised like a trumpet. This trait is taken from nature; all dogs in Egypt carry their tails curled up like this

(Jean-François Champollion’s Egyptian journal,

Alexandria, August 1828)

The idea of a joint Franco-Tuscan expedition to Egypt led by Champollion and Rosellini had been in the air since the two scholars had visited Florence in mid-1826, when Champollion had seductively written Grand Duke Leopold II’s name as a hieroglyphic cartouche in the grand-ducal art gallery, along with an accompanying description: ‘Most Gracious Sovereign’. The two had then travelled to Naples and outlined the same idea to the duke of Blacas, for him to raise with King Charles X. But even if Leopold II of Tuscany was willing to support the expedition from the outset, the French government had required more persuasion. Joint initiatives – with shared responsibilities and shared prestige – were not Charles X’s normal style. The king had been finally won over in the spring of 1828 by a combination of influential courtiers and politicians: Blacas, Rochefoucauld, Doudeauville and the king’s new prime minister, the viscount of Martignac, who favoured closer political ties between Paris and Florence – not to mention the appealing possibility of sharing the expedition’s total cost, 90,000 francs, with the Tuscans.

In their official proposals, written in mid-1827, Champollion and Rosellini argued that the prevailing level of understanding of Egyptian art – its architecture, sculpture and painting – was essentially inadequate, indeed false. The great French expedition of 1798–1801 and the subsequent Description de l’Égypte (still not quite completed in 1827) had laid the groundwork for a more informed understanding. Now was the time to go deeper into the subject, the two proposals argued – just as Champollion himself was already arguing on behalf of the displays and captions in the new Egyptian gallery at the Louvre – with the benefit of ‘the new knowledge acquired from the writings of ancient Egypt’ as a result of the decipherment, which would guide an expedition of savants and artists consisting of ‘a small number of well-prepared persons’.

Another point in the expedition’s favour was the rapid destruction of ancient Egyptian monuments that had begun soon after the turn of the century. These had survived for more than two millennia remarkably well until the time of Napoleon’s expedition, but were now suffering through a combination of disuse (apart from those temples converted into Christian churches), geographical isolation and lack of interest from the surrounding population – except, that is, for local treasure hunters looking mainly for gold and jewels in the tombs and pyramids. Neither the Arabs who ruled Egypt from 642, nor the Ottoman Turks who took over from the Arabs in 1517, regarded ancient Egypt and its remains, including of course the hieroglyphs, as part of their cultural heritage. But in the quarter century that followed the French withdrawal from Egypt in 1801, there had been a highly destructive mixture of pillaging for antiquities (such as the Dendera Zodiac, the Philae obelisk and the sarcophagus of Seti) by European excavators (notably Belzoni, Bankes, Drovetti and Salt) and the demolishing of monuments for fertilizer, lime and building stone by the regime of Muhammad Ali Pasha, in his drive to modernize Egypt. In his later years, the pasha even encouraged French engineers to dismantle part or all of the Pyramids at Giza to obtain stone for dams across the River Nile. ‘Between 1810 and 1828 thirteen entire temples were lost and countless objects were removed from their contexts,’ notes Patricia Usick in her biography of Bankes, Adventures in Egypt and Nubia. Unless Champollion’s expedition were to set off quickly, he would almost certainly find that many of the finest Egyptian monuments and works of art had vanished from their original locations.

In the end, it was agreed between the French and Tuscan rulers that Champollion would have responsibility for the general direction of the joint expedition; Rosellini would be the second-in-command, with responsibility for all the details of its execution; and Charles Lenormant would be its inspector general, representing Rochefoucauld and the French government. The two commissions consisted of seven persons each. On the French side: Champollion and Lenormant; an architect called Antoine Bibent (whom Champollion had met in Naples); three painters named Alexandre Duchesne, Pierrre-François Lehoux and Édouard Bertin; and Nestor L’Hôte, a young customs officer with a passion for Egyptology, who would prove to be a good artist. On the Italian side: Rosellini; his architect uncle Gaetano Rosellini; his artist brother-in-law, Cherubini (who regarded himself as a Frenchman); a painter, Giuseppe Angelelli; a well-known naturalist from Florence, Giuseppe Raddi, and his assistant, Gaetano Galastri; and a medical doctor from Siena, Alessandro Ricci, who had travelled in Egypt with Bankes and had become Henry Salt’s physician. After saving the life of the son of the Egyptian pasha, Ricci had become the son’s personal physician, received a large gift and retired to Italy, where he set up an antiquities museum and sold portfolios of his Egyptian drawings and journals that Champollion had much admired on his visit to Florence in 1825. To Champollion’s disappointment, he was unable to include his friend from his days at Turin’s Egyptian Museum, the Abbé Gazzera.

Everything now depended on the permission of the Egyptian authorities – which in practice meant Muhammad Ali, who had been the effective ruler of Egypt since 1805 (even if he was nominally the viceroy of the Ottoman sultan), closely advised by the French consul-general in Egypt, who in 1828 was still Drovetti. While the pasha was motivated by politics, with a decided tilt towards France, and was indifferent to Egyptology, Drovetti’s motives were more inscrutable – at times almost indecipherable. Drovetti would give some aid to Champollion in Egypt, but would also create many difficulties for him.

Four years earlier, before Champollion left Paris for Italy in 1824, Drovetti had encouraged him through one of their mutual contacts to come to Egypt on a study tour, for which he promised all necessary help. At this time, an official invitation from Muhammad Ali did not appear necessary, because Drovetti was confident that such a leading French scholar as Champollion would be welcomed by the Francophile pasha. But when Drovetti turned up in Paris in mid-1827, at the time of the installation of his second collection at the Louvre, the consul-general was no longer so full of encouragement.

The obvious reason was the deteriorating political relationship between Egypt and France, which reached a nadir in October 1827 after the battle of Navarino. There, as part of the Greek struggle for independence from the Ottoman Empire, a combined French, British and Russian fleet had wreaked havoc on the fleets of Ottoman Turkey and Egypt. French visitors to Egypt, however apolitical, were now unlikely to be welcome, although the pasha had guaranteed the protection of French residents in the period following the battle.

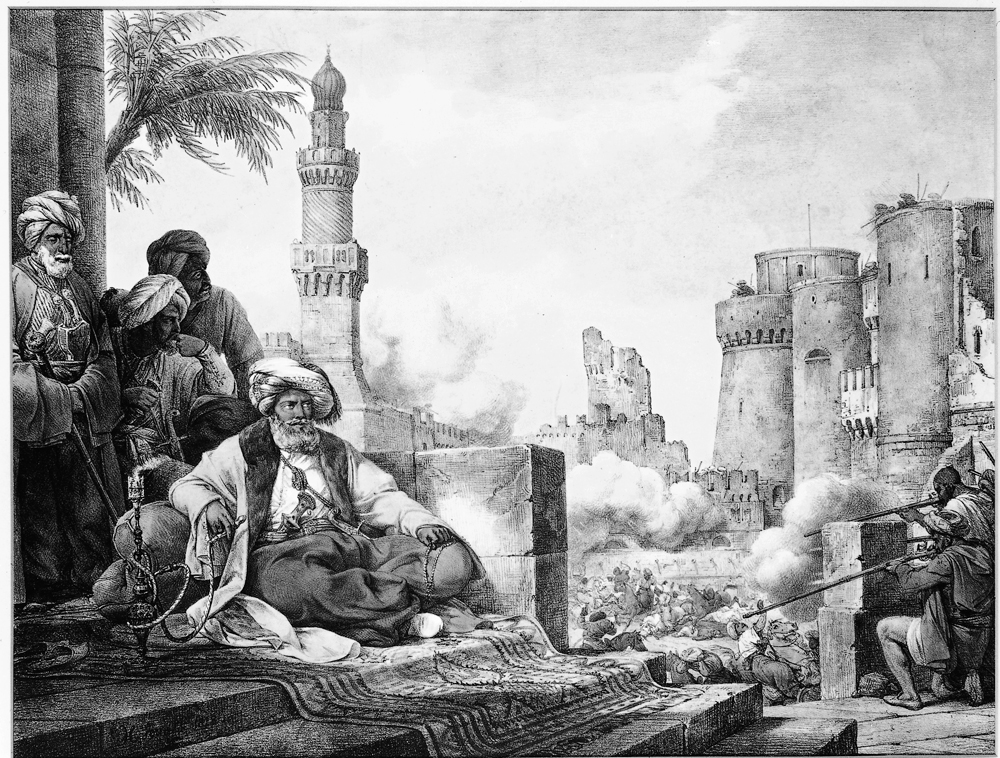

Muhammad Ali Pasha, viceroy of Egypt and its effective ruler from 1805 to 1848. Here, he watches his soldiers massacring the Mamluks at the Cairo Citadel in 1811, in an engraving after Horace Vernet. Muhammad Ali was largely indifferent to ancient Egypt.

(Massacre of the Mamluks, engraving by Godefroy Engelmann after Horace Vernet.)

Less obviously, Drovetti now had the excavation of Egyptian antiquities largely to himself, because of the withdrawal of his long-time rival, the British consul Salt, who died in October 1827. The appearance of Champollion on the Egyptian scene, far from having the potential benefit of winning advantage with the pasha over the British, would in fact tend to interfere with the French consul’s trade in Egyptian antiquities. Although Drovetti never openly admitted his commercial motive, it was plain from his actions. For, despite his claims to the contrary, he did not inform Muhammad Ali about the planned Franco-Tuscan expedition in order to obtain the pasha’s permission; instead he sent two letters to Champollion and Rosellini warning them not to come to Egypt in 1828.

Bernardino Drovetti, the French consul in Egypt, with members of his expedition to Upper Egypt in 1817-18. Drovetti both assisted and hindered Champollion.

(Bernadino Drovetti in Egypt. Anonymous lithograph, 19th century.)

Drovetti’s letter to Champollion, written from Egypt on 3 May 1828, advised him to delay his expedition for political reasons:

There reigns in Egypt, as in all of the other parts of the Ottoman Empire, a spirit of animosity against Europeans, which, in certain cases, could produce ferment and seditious unrest against the personal security of those domiciled there or who find themselves travelling there. If the situation depended only on the will of Muhammad Ali to put a stop to the effects of this discontent, it would not be difficult to obtain what you have given me the responsibility of requesting, but he himself is a target of this animosity because of his European principles and sympathies, and he does not dare to give the guarantees that I have requested on behalf of you and your travelling companions.

This letter reached Paris after Champollion had left the capital, heading for Lyons and thence to his expedition vessel waiting in the harbour at Toulon. Champollion-Figeac opened it and immediately smelt a rat: some kind of intrigue by Drovetti, or perhaps Drovetti acting in league with his very close friend Jomard. Champollion-Figeac knew that cancellation of the expedition would devastate his brother. So it appears that the canny Jacques-Joseph sat on Drovetti’s disturbing missive for a few days and did not forward it to Jean-François at Toulon until 28 July. The government in Paris did not act until 1 August, when the appropriate minister sent a message to the naval station in Toulon by the new system of telegraphic communication, asking the admiral urgently to inform the prefect in Toulon to detain the expedition. But the telegram arrived too late: around midday on 31 July, the wind was favourable and the commander of Champollion’s corvette raised anchor and set sail towards the east. Champollion eventually heard about the letter from Drovetti in person, when he reached Alexandria. Had he known about it before leaving Paris, he wrote to his brother from Egypt in late August, he would not have set out: ‘It is the hand of Amun that diverted it.’ At this stage Champollion knew nothing of the hand of Champollion-Figeac.

Fortune favoured Champollion in a second way, too, during the week before his departure. Nearing Toulon, he made a detour to Aix-en-Provence to see some hieratic papyri belonging to François Sallier, a local revenue official, former mayor of Aix and a friend of the count of Forbin. On the second day, Sallier showed Champollion some rolls that struck him as being of the greatest importance. Two of them contained what he thought were ‘types of odes or litanies’ in praise of a certain pharaoh, as he told his brother. Another roll, whose first pages were missing, consisted of ‘eulogies and exploits of Ramesses-Sesostris in a biblical style, that is to say, in the form of an ode in which the gods and king converse’. There was no time to study the manuscripts in depth, so Champollion requested Sallier not to show them to anyone else until he returned from Egypt – a request that Sallier apparently granted. (After Sallier’s death in 1831, the papyri were eventually sold to the British Museum and catalogued as ‘Sallier II’; a note on one sheet of the ‘odes and litanies’ states that it was ‘stuck onto fourteen squared sheets by Champollion at M. Sallier’s in the month of February 1830’.)

To Champollion, the importance of the ‘eulogies and exploits’ lay in their refining of his decipherment and the historical information they imparted. He obtained from them the names of some fifteen conquered nations, including the Ionians, Lycians, Ethiopians and Arabs, and information about the chiefs who had been taken hostage, as well as the payments required from those nations. This enabled him to identify a pair of hieratic signs used to specify the names of foreign countries and individuals given in a foreign language. ‘I have carefully noted down all the names of the conquered peoples which, being perfectly readable and in hieratic script, will help me to recognize those same names in hieroglyphic on the monuments of Thebes, and to restore them, if they are partly worn away,’ he told his brother in mid-1828, giving us an inkling of his formidable preparation for the expedition and of the comparative working methods he would adopt in Egypt.

For today’s Egyptologists, too, Papyrus Sallier II is of great importance – but for literary rather than historical reasons. According to Richard Parkinson in his anthology of ancient Egyptian poetry, ‘The rediscovery of ancient Egyptian literature can be dated precisely to the 22 July 1828’ – the day that Champollion came across the ‘odes and litanies’. In actuality, Champollion had discovered a copy of ‘The Teaching of King Amenemhat’, a text composed around 1900 BC and probably copied in Memphis in 1204 BC, during the 19th dynasty. It was written by a treasury scribe called Inena in ‘Year 1, month 1 of winter, day 20’, under Seti II. Amenemhat was the founder of the 12th dynasty, who ruled c. 1938–1908 BC, but he cannot have been the author of the poem, since the king speaks to his son and heir in a dream from the grave, telling him of an attempted palace assassination (apparently his own) and giving him advice on how to rule. Champollion, writes Parkinson, ‘did not recognize its literary character, since at that time preclassical literature – with the exception of the Bible – was little regarded’.

The expedition’s voyage eastwards along the Mediterranean went smoothly, although the corvette was prevented from landing at Agrigento, where the group wanted to visit the site of the ancient Greek city of Akragas, by Sicilian officials who had heard rumours of plague in France. Champollion’s first sighting of Africa was through a telescope. He was able to pick out Berber shepherds, their tents and flocks in the hills and valleys of Cyrenaica (eastern Libya). On the afternoon of 18 August he spotted Pompey’s Pillar and the harbour at Alexandria through the telescope. The corvette’s commander fired a cannon shot, which beckoned from the harbour an Arab captain, who piloted the vessel past French and English ships charged with blockading the harbour and moored her among European vessels, not far from some Egyptian and Turkish ships still undergoing repair after the battle of Navarino almost a year earlier. The cosmopolitan mingling of ships of all nations, friends and enemies, struck Champollion as a very strange spectacle, characteristic of the period. Then the secretary of the French consulate came on board, welcomed him in the name of Drovetti, and a meeting was arranged with the French consul for that very evening. The Tuscan consul, Carlo Rosetti, also sent a message via his Turkish janissary (a type of retainer), Moustapha.

The corvette’s commander wished to meet Drovetti, too, so together with Champollion and Rosellini the three men set off in the commander’s rowing boat, weaving their way through the crowded harbour for a good half-hour until they reached the customs house. Champollion’s description of their first steps onto Egyptian soil, written for his brother, is vibrant with life and humour:

Preceded by two janissaries from the consulates of France and Tuscany, who, with their white turbans, their flowing red robes and their silver-knobbed canes, recall the ancient doryphores [spear-carriers] of the kings of Persia, we took a few steps towards the gate of the city. But scarcely had we cleared the customs house than a crowd of young boys, clothed in rags and leading rather pretty donkeys, surrounded us with much shouting, and forced us to accept their modest palfreys, which had saddles that looked clean enough and were braided in all colours. Thus we were now in a cavalcade, led by the two janissaries who had also grabbed themselves a donkey each, and made our first entrance into the ancient residence of the Ptolemies. It is fair to say that the donkeys of Egypt, which are the hackney carriages of Alexandria and Cairo, merit all the praise given them by travellers, and that it is difficult to find a mount with a gait that is gentler and more agreeable under all conditions. One is compelled to hold the bridle to prevent it from breaking into a trot or a gallop. A bit bigger than those of Europe, and above all more lively, Egyptian donkeys hold their ears to perfection, almost upright and cocked with a certain pride. This comes from the fact that, at an early age, young donkeys have their ears pierced, which are then pulled together with a string of horse hair and fixed in place with a second string, in such a way as to make the ears acquire a vertical position. In addition, these animals have a very smooth coat; some are brown or black, but the majority are reddish grey.

Champollion’s journal of the expedition, based on his letters to his brother and some others in France and Italy, is as rich in observations of contemporary Egyptian life as it is in comment, analysis and sketches concerning ancient Egyptian art and scripts. Everywhere he travelled, he could not help but compare the ancient with the modern, despite the long intervening centuries of Muslim rule. Fascination with the land and affection for its people, even for some of its harsh rulers, dominate his words, but criticism and exasperation are never far from the surface. In fact, of all his writings, the journal probably gives the clearest picture of his personality. Champollion had always been an enthusiast for life; in Egypt he showed himself to be a poet, too. But he never allowed himself to be distracted from the ancient Egyptians and their hieroglyphs for long. After a day spent wandering among the wonders of Cairo’s mosques, minarets and arabesques, he remarked to his brother: ‘There is enough of the old Egypt, without occupying myself with the new.’

Champollion’s interview with Drovetti on the evening of his arrival appeared to go well. Although the consul reiterated what he had said in his ‘diverted’ letter, he added that the political situation had recently improved somewhat: Muhammad Ali and the British had signed a treaty in Alexandria in early August, agreeing to an evacuation of Egyptian troops from Greece. Drovetti was therefore now certain that Champollion’s expedition would receive permission from the pasha to proceed up the Nile to Cairo and beyond, along with official permits and facilities. His own house in Alexandria would be put at Champollion’s disposal, and another rented for his travelling companions. After spending one more night aboard the corvette, the expedition fully disembarked on 19 August 1828 and settled down in Alexandria. Champollion found himself staying in the same room as had General Kléber, Napoleon’s successor in Egypt and the celebrated victor over the Turks at the battle of Heliopolis in 1800.

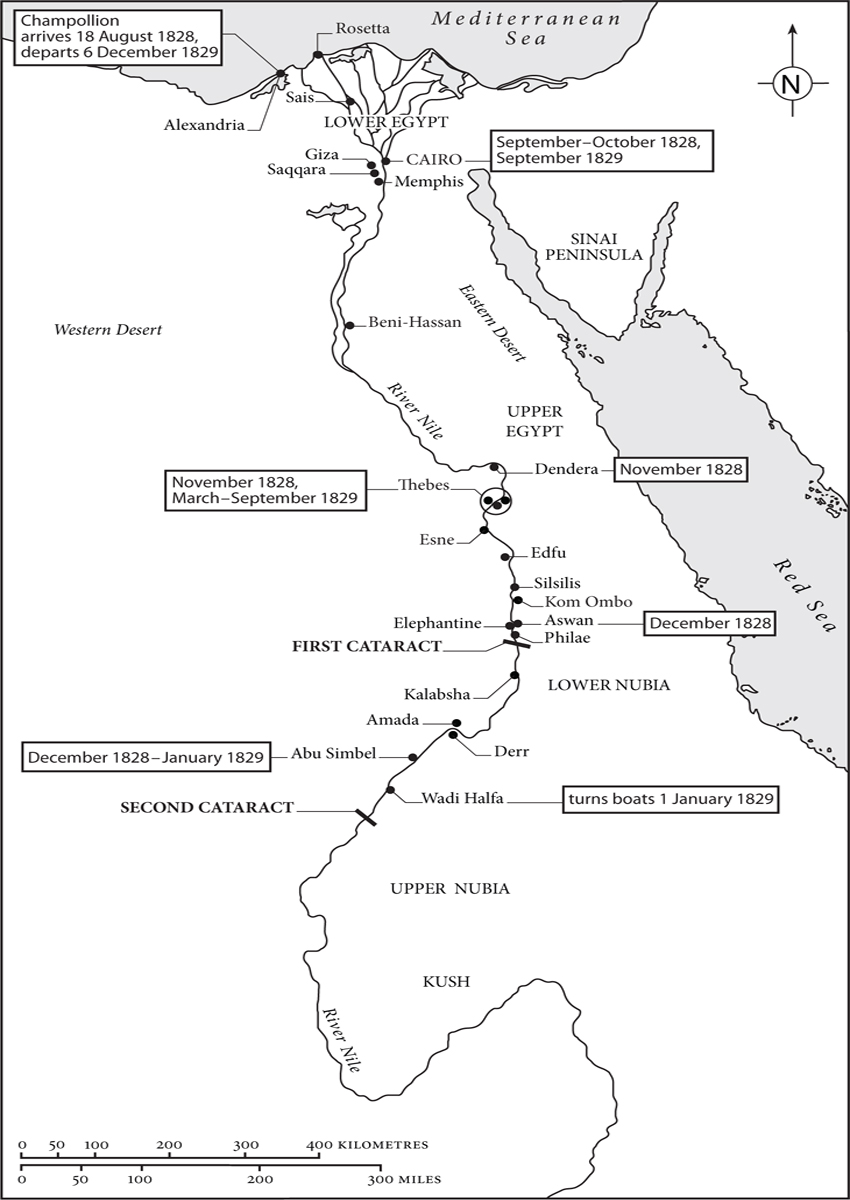

Map of Egypt with the main sites visited by Champollion and the Franco-Tuscan expedition.

The following evening – on his first full day in Alexandria – a restless Champollion was determined to see Cleopatra’s Needles. These two obelisks were outside the city proper, where they would remain until one was moved to London and erected in 1878 and the other transferred to New York shortly after. To reach them Champollion had to walk, followed by a large number of dogs, across bare mounds of debris – pottery, glass, marble and other materials mixed with sand – that had covered the remains of ancient Greek and Roman buildings. Some of the high arches of these structures poked up through the debris like the low mouths of caverns, inside which Champollion saw families of peasants dwelling in miserable circumstances – the earliest of his many contacts with the grinding poverty of Egypt under the pasha’s rule. A blind old Arab guided by a young half-naked child accosted him: ‘Good day, Citizen, give me something, I have not yet had lunch.’ Stunned by this Republican greeting, Champollion found some French coins in his pocket and put them into the blind man’s hand. The Arab felt them for a moment then called out: ‘These are no longer in use, my friend!’ So Champollion produced a Turkish piastre. ‘I thank you, Citizen!’ cried the old Arab. ‘At each moment in Alexandria one comes across old souvenirs of our campaign in Egypt,’ Champollion mused to his brother in Paris.

One of the obelisks was still upright, while the other had long since fallen in the sand. Both were made of pink granite, like those in Rome. Champollion noted that:

A quick examination of their three columns of hieroglyphs, inscribed on each of their faces, informed me that these beautiful monoliths were carved, consecrated and erected in front of the temple of the Sun at Heliopolis by Pharaoh Thuthmosis III … The lateral inscriptions were added afterwards in the reign of Ramesses the Great; and the royal inscription of Ramesses VII … was carved on the northern and eastern faces between the lateral inscriptions and the tip of the obelisk, but in very small hieroglyphic characters. – So the obelisks of Alexandria go back to pharaonic times, as the beauty of their workmanship alone demonstrates, and were carved in three different periods, but always in the 18th dynasty. It was the first European travellers or the first French to settle in Alexandria who gave these monuments the name Cleopatra’s Needles, an appellation as inexact as the name Pompey’s Pillar, applied to a monument of the late Roman period.

Champollion was correct about Thuthmosis III and Ramesses the Great, and about the obelisks’ lack of connection with Cleopatra: in fact they had been moved from Heliopolis to Alexandria in 10 BC, two decades after her death, during the reign of the Emperor Augustus, to stand in front of a temple to the recently deified Julius Caesar. As for Pompey’s Pillar, it was erected by the Emperor Diocletian in AD 297, not by Pompey in the 1st century BC. So Champollion’s analogy was sound. Sadly, the hieroglyphs on both obelisks are now so badly eroded by the climate and pollution of London and New York that many are barely legible.

On 24 August 1828, six days after the expedition’s arrival, Drovetti presented Champollion, Lenormant and the commander of the corvette to Muhammad Ali Pasha. They talked in French, since the pasha, who was a Macedonian of Albanian parentage, did not know Arabic. Apart from the hookah pipe inlaid with diamonds held in his hands, what struck Champollion most about Muhammad Ali was his simplicity and his vivacious eyes, which contrasted strangely with a white flowing beard that reached his stomach. The pasha came to the point without any excess of Oriental politesse and immediately granted the expedition permission to travel up the Nile to the second cataract. Furthermore, he appointed two guards to accompany them to ensure their proper treatment. After some talk about the Egyptian military situation in Greece over a cup of sugarless coffee, the visitors took their leave. Champollion immediately started making plans to depart Alexandria as soon as the permissions were in his hands and the August heat had abated.

But now Drovetti again interfered. No permissions were forthcoming from the pasha for well over a week. Champollion, emboldened by his audience and by his usual courage in the face of opposition, decided that there was now no option but to make an official protest to the French consulate. Through his own research, he had become convinced that Drovetti had all along been hindering him, chiefly for commercial reasons of his own. He therefore informed the consulate that, having come to Egypt on an official research mission for the royal museums in Paris, were he unable to discharge his mission he would be obliged to explain to the king’s ministers the reasons why, which appeared to him merely a matter of commercial intrigue. Not only would this failure be an affront to Charles X, it would also damage Muhammad Ali’s reputation in Europe for being a guardian of the arts and sciences – especially since the French–Italian mission, unlike those undertaken by previous visitors who had received permits (such as Belzoni and Passalacqua), was not pursuing its own commercial gain. A copy of this letter went to Minister Boghoz, who represented the pasha.

It was a somewhat risky strategy, but the official protest worked, bolstered as it was by public opinion in Alexandria and, more significantly, by the Egyptian government’s fear of bad publicity in the French newspapers, which Champollion had shrewdly emphasized as a threat – no doubt aimed mainly at Drovetti. The pasha’s permits arrived on 10 September, even including the right to visit locations formerly reserved to the French consul and his Swedish counterpart. The biographer of Drovetti, Ronald Ridley, somehow manages to credit this satisfactory resolution to the ‘skills and generosity’ of his subject, but it is hard to acquit the French consul of simple greed, in trying to corner the Egyptian antiquities trade, and of short-sightedness, given that he had already sold a collection to the Louvre in 1827 and was unlikely to sell another to the French king if he contrived to infuriate the museum’s curator of Egyptian antiquities.

In the end, the pasha did the expedition proud. Apart from the permits and the guards, he provided a large sailing boat of a type known as a maasch, one of the largest in the country, which Champollion named Isis. A second, much smaller boat, known as a dahabieh, big enough for five people to sleep in, was hired by Champollion and Rosellini, named Athyr (Hathor), and put under the command of Duchesne instead of the naturalist Professor Raddi, who had temporarily left the expedition to chase butterflies in the Libyan desert. ‘So we shall sail under the auspices of the two most jolly goddesses of the Egyptian Pantheon,’ Champollion wrote to his brother on 13 September. The total number on board both boats, including the sailors, the pasha’s guards, a dragoman interpreter, two Nubian servants and a cook, was thirty people. Drovetti provided some bottles of superior French wine for the Isis, but would take his revenge on Champollion by failing to forward his mail from France.

Champollion was determined not to dawdle in the Nile Delta, where he knew from the Description de l’Égypte – in so far as it was trustworthy – that little of note remained above ground. His only major stop on the way to Cairo was at the site of ancient Sais, a town mentioned as significant by Herodotus, Plato and Plutarch. But there was not much to be seen, partly because of the destruction of ancient buildings by the locals over many centuries, and also because the site was inundated by the annual floodwaters of the Nile; the waterlogged modern cemetery created a foul stench, strongly suggesting to Champollion one cause of the plague in modern Egypt. (Even so, he continued to drink Nile water, as a matter of pride.) Early on 19 September, when the haze lifted, they caught their first sight of the pyramids at Giza; at first only two were visible, then all three came into view as they sailed nearer to Cairo. Champollion had a drawing made of the magnificent vista. While the boats were briefly moored to adjust their rigging, he also saw his first scarab beetle, brought to him by a sailor. The beetle’s habit of rolling a ball of dung along the ground was linked by the ancient Egyptians with Khepri, a creator god associated with the sun god Ra, responsible for rolling the sun through the sky from east to west; Khepri is depicted in the hieroglyphic script as a scarab beetle. In the late afternoon, the party beached their maasch and dahabieh, along with many other similar boats, on the riverbank at Bulaq, the port of Cairo, and prepared to travel in several convoys of loaded donkeys and camels for some days’ stay in the fabled capital.

Despite Cairo’s mixed reputation among Europeans, including Napoleon and his savants in 1798–1801, the city appealed strongly to Champollion. The common European criticism that Cairo (and Baghdad) had no wide streets, unlike Paris and London, struck him as stupid, because it did not take account of the Egyptian climate: wide streets in Cairo would have been furnaces for three-quarters of the year. Moreover, he pointedly noted – no doubt thinking of the mud and filth in Paris from which he suffered – that the streets of Cairo were remarkably clean and free from litter.

All over the city, in the stones of old buildings, he saw signs of the ancient past. In the most important room of the old palace of Saladin, the famous 12th-century Ayyubid sultan of Egypt and Syria, Champollion noticed thirty columns of pink granite of Greek or Roman origin. They were topped with Arab capitals whose stone was originally quarried from the ruins of Memphis and still carried traces of hieroglyphs, including a bas-relief of King Nectanebo (the last Egyptian ruler before the arrival of the Persians and the Greeks) making an offering to the gods. ‘Thanks to the Thoulounid dynasty, to the Fatimid caliphs, to the Ayyubid sultans, and to the Bahriyya Mamluks, Cairo is still a city of a Thousand and One Nights,’ Champollion told his brother, ‘although Turkish barbarism has destroyed or allowed to be destroyed in large part the delightful artistic products and civilization of the Arabs.’ He gave a subtle example of the latter from an evening concert he attended at the house of the pasha’s physician. There the expedition party sat on a great divan while smoking and drinking coffee, and listened to female Arab singers discreetly veiled from male view by a curtain. But the performance was spoiled by the way in which the singers were encouraged to push their art to extremes so as to pander to the prevailing Turkish taste. The husband of the best singer, Nefisseh, loudly applauded and interrupted his wife’s singing to encourage her, ‘in the tone with which Blue-Beard called his wife to cut off her head’.

Scarab beetle pushing a ball of dung – the inspiration for the ancient Egyptian myth of the creator god Khepri and the moving sun, often depicted in pharaonic tombs.

(Photo blickwinkel/Alamy.)

The fountain of Tusun Pasha in Cairo, depicted by Robert Hay in Illustrations of Cairo, published in 1840. Contemporary Cairo fascinated Champollion almost as much as ancient Egypt.

(Engraving of the fountain of Tusun Pasha, from Robert Hay’s Illustrations of Cairo, 1840.)

Cairo’s charms soon proved too enticing for the younger members of the expedition, and by the end of the month its leader was anxious to leave the city for the desert. They sailed on 1 October from Bulaq and the next day stopped to visit ancient stone quarries at the foot of a range of mountains. Champollion, by now thoroughly Arabized in both dress and speech, and with a growing beard, walked the considerable distance to the site wearing a burnous and protected by an umbrella from the strong sun. Under his instructions, the expedition members each explored a different cavern in the mountainside and whistled to him if they came across an inscription or sculpture. Champollion then went and determined how important it was, and either sketched the inscription himself or had a drawing made if the signs were clear enough to the others. The inscriptions were in both hieroglyphic and demotic. Some contained royal cartouches and dates: one example included the name of Achoris (Hakor), a ruler from the early 4th century BC – one of the earliest pre-Ptolemaic cartouches Champollion had deciphered and published in the Lettre à M. Dacier. On the stone ceilings red lines were sometimes visible, accompanied by demotic words consisting of technical instructions written by the ancient quarrymen.

Head of the fallen colossus of Ramesses II at Memphis, as drawn by the Franco-Tuscan expedition.

(Photo Andrew Robinson.)

At the site of ancient Memphis, Champollion was overwhelmed by the fallen colossus of Ramesses the Great, sculpted from limestone and clearly identifiable by its cartouches. After detailed study and the making of a sensitive drawing, Champollion concluded that the head of the statue was a faithful copy of the smaller colossus of Ramesses the Great at Turin he had profoundly admired. Harping on a favourite theme, he told his journal: ‘Any impartial man may recollect a type of dread mixed with disgust that cannot be avoided in Rome, as I felt, in front of the colossal heads of the emperors preserved on the Capitol and elsewhere; would that he might compare this feeling with his experience before the head of an Egyptian colossus.’ Curiously enough, the more Champollion discovered of Ramesses the Great – at Thebes, Abu Simbel and other sites – the more he idealized this most vainglorious of pharaohs, celebrated for an imperial ambition worthy of Napoleon Bonaparte.

By comparison with Memphis, the necropolis of the Memphites on the nearby plateau of Saqqara, about 16 kilometres (10 miles) from Giza, was a deep disappointment. Saqqara had been used as a burial site from the beginning of the 1st dynasty (3100 BC) until the late Christian period that followed the end of the Roman Empire – that is, some three-and-a-half millennia. But after this huge span of time, the necropolis had lain abandoned for well over a thousand years, left to the busy attentions of tomb robbers. Champollion’s journal again:

We managed to climb the mountain, and, when we got to the plateau at the top, we could form for ourselves an idea of the devastation that people have wreaked over the centuries on the burial places of the Memphites. The vast expanse interrupted by pyramids was riddled with hillocks of sand covered in debris consisting of shards of ancient pottery, wrappings from mummies, shattered bones, the skulls of Egyptians whitened by the desert dew, and other stuff. At every moment one encounters under one’s feet either the remains of a dried-brick wall or the opening of a square shaft, dressed in beautifully cut stone but more or less filled up with the sand that the Arabs have dug away to get at the shafts. All these hillocks are the result of excavations in search of mummies and antiquities, and the number of shafts or tombs at Saqqara must be enormous, if you consider that the sand thrown up in discovering one shaft must itself hide the openings to several other shafts.

Although Champollion decided to camp in this bleak setting, only two of the tombs proved fruitful. In one he discovered a series of birds admirably sculpted on the walls, with their accompanying hieroglyphic names, five species of gazelle, with their names, and a few domestic scenes, such as the milking of cows and two cooks showing off their culinary arts. The other tomb had walls covered with now familiar scenes from the Book of the Dead, but the vaulted ceiling was of great interest. It was covered with bas-reliefs representing the twelve hours of the day and the twelve hours of the night – a division of time apparently conceived by the Egyptians – in the form of women, each carrying a star on her head. Daytime was on the left side of the vault, nighttime on the right. The concept of ‘hour’ was expressed in the hieroglyphic group

in which Champollion recognized the root of the Coptic word for ‘hour’ and its plural, ‘hours’. ‘The star  is the determinative of all divisions of time,’ he noted in his journal, and then added: ‘Each of these hours has its own particular name among the ancient Egyptians … I am collecting them here in the hope of completing this list in some tomb at Thebes.’ The term he had coined, ‘determinative’, describes a concept integral to hieroglyphic script that seems to have occurred to Champollion in Egypt, since it made no appearance in the second edition of his Précis du système hiéroglyphique des anciens Égyptiens (1828). Although he would not have time to develop this ‘grand discovery’ (Edward Hincks’s description in 1847) fully before his death, the Egyptologist John Ray goes as far as to call Champollion’s concept of the determinative ‘probably his greatest single achievement’ as a scholar. We shall return to it in Chapter XVI.

is the determinative of all divisions of time,’ he noted in his journal, and then added: ‘Each of these hours has its own particular name among the ancient Egyptians … I am collecting them here in the hope of completing this list in some tomb at Thebes.’ The term he had coined, ‘determinative’, describes a concept integral to hieroglyphic script that seems to have occurred to Champollion in Egypt, since it made no appearance in the second edition of his Précis du système hiéroglyphique des anciens Égyptiens (1828). Although he would not have time to develop this ‘grand discovery’ (Edward Hincks’s description in 1847) fully before his death, the Egyptologist John Ray goes as far as to call Champollion’s concept of the determinative ‘probably his greatest single achievement’ as a scholar. We shall return to it in Chapter XVI.

And now the expedition proceeded to the pyramids and the Great Sphinx at Giza. Here, a mystery arises. Champollion’s journal for 8 October records his impression – familiar to many visitors – that the pyramids are grand from afar, but that as one approaches them they seem to become reduced, until one is close enough to touch them, when the marvel of their construction asserts itself. He also notes his urge to excavate the sand from around the Sphinx in the hope that he would be able to read the inscription of Thuthmosis IV carved on its chest, but that he has been discouraged by a throng of local Arabs who estimate that the task would require forty men working for eight days. Finally, he adds that he has set up his tent more or less alone on the eastern edge of the Giza plateau, because most of the expedition has preferred to sleep in a nearby series of tombs or in a house belonging to Giovanni Caviglia. This eccentric Italian excavator had attempted to enter the middle of the three great pyramids in 1817, the year before Belzoni succeeded in this feat. At this point, however, Champollion’s journal simply stops for reasons unknown – and does not resume until 20 October.

Sketch of the Sphinx by Champollion. Its actual inscription was covered by sand.

(Sketch by Champollion of the Sphinx at Giza. Photo Andrew Robinson.)

As a result, almost nothing is known about Champollion’s activities in the two days between his arrival at the Giza pyramids on 8 October and his departure on 11 October. During this interval, according to the memoirs of the expedition member L’Hôte, on 9 October the two commissions, French and Italian, entered the long corridors inside the Great Pyramid, led by an Arab, with just two candles for illumination in the overheated, bat-smelling atmosphere. They felt a mixture of admiration and terror. But there was complete silence about this intriguing visit from the normally loquacious Champollion. Did he accompany them or not? One surprising speculation, mentioned by Hartleben, is that Champollion spent this two-day period with a secret society dedicated to the wisdom of the ancient civilizations, known as the ‘Brothers of Luxor’, of which Caviglia was an enthusiastic member and to which the recently deceased Salt had also belonged. A modern Egyptologist, Christian Jacq, has woven a charged relationship between Champollion and Caviglia into the plot of an implausible romantic novel based on Champollion’s Egyptian journey. Nonetheless, the idea of a relationship between Champollion and the Brothers of Luxor has some slight credibility, given his lifelong devotion to ancient Egypt, and to Thebes (modern Luxor) in particular, and the fact that he is known to have spent time with Caviglia in Florence – not to mention his past membership of secret political societies in Grenoble. But if Champollion really did become one of the mystical Brothers, he never gave so much as a hint of it, even to his own cherished brother.

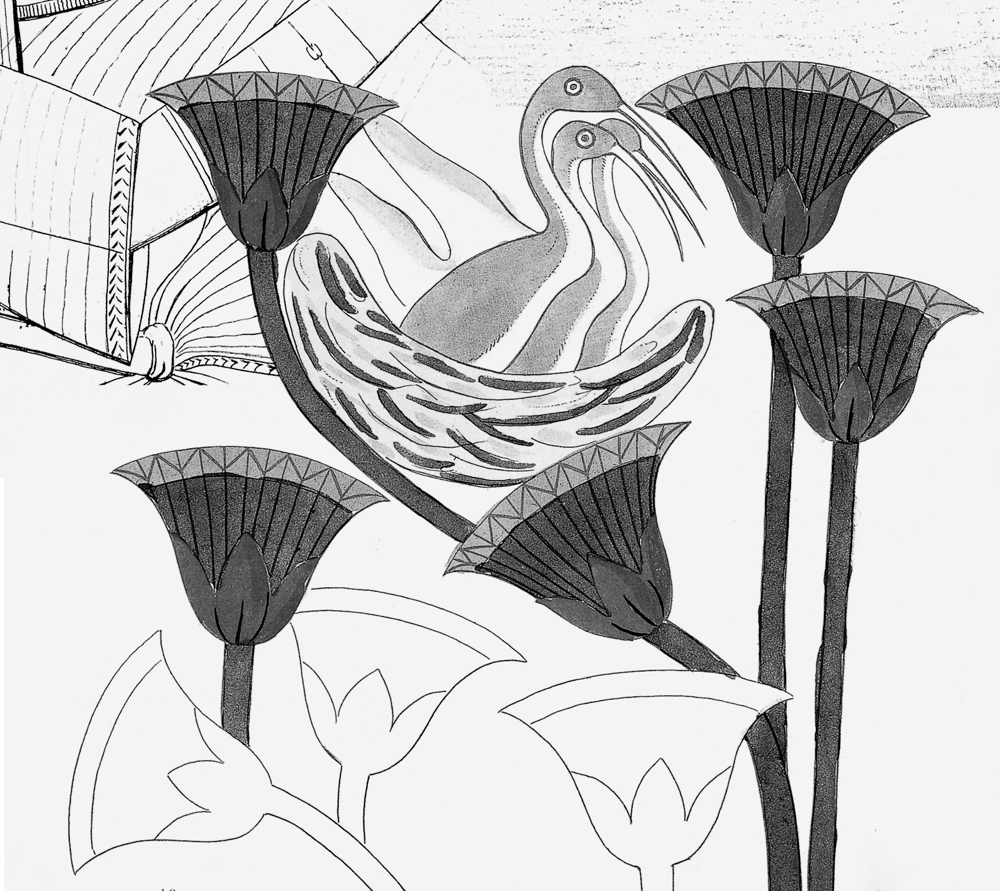

On 5 November, after a long silence, Jean-François told Jacques-Joseph that he had expected to be in Thebes by 1 November, and every night was dreaming of scenes in the palace of Karnak. However, ‘Man proposes, my dear friend, and God disposes.’ In fact, the expedition had covered less than half the distance between Cairo and Thebes and become bogged down at Beni-Hassan. For this delay Champollion bluntly blamed Jomard, as he would frequently do throughout the expedition, complaining of the poor quality of the information and drawings in the Description. The book’s write-up for Beni-Hassan had given Champollion no inkling of the wonders that awaited him there. On the walls of a grotto, using simply a wet sponge to remove a crust of fine desert dust, the expedition had uncovered a fabulous series of murals depicting ordinary life, crafts, the professions, and even, for the first time, the military caste: ‘The animals, quadrupeds, birds and fishes are painted there with such subtlety and lifelikeness that the coloured copies I have had taken resemble the coloured engravings of our best natural history books: we shall need the evidence of all fourteen witnesses who saw them to make Europe believe in the faithfulness of our drawings, which are absolutely exact.’

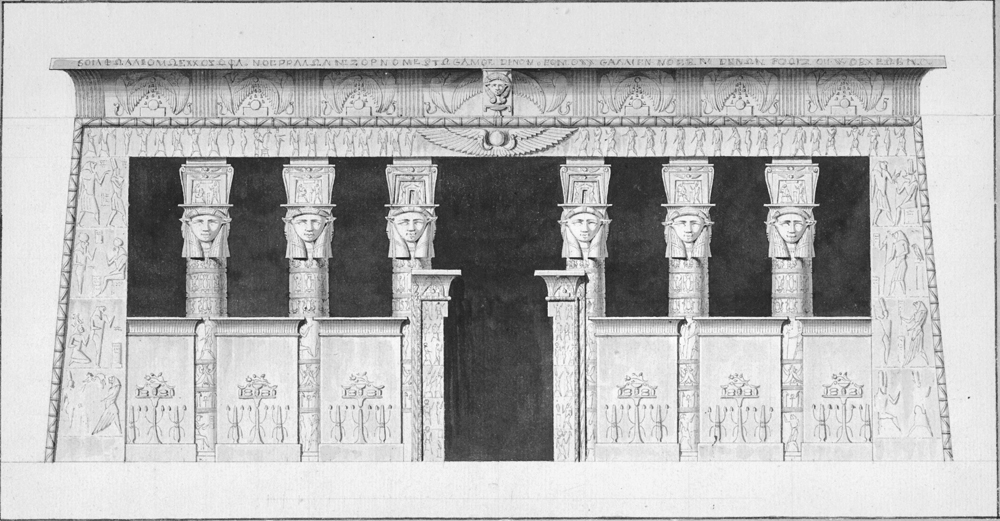

On the evening of 16 November, after several stops en route, they at last reached Dendera, just north of Thebes – the erstwhile location of the notorious zodiac in Paris. This had been cut from the ceiling of the great temple, leaving behind the controversial cartouche for ‘Autocrator’ that had made Champollion an unwitting champion of the true Catholic faith six years earlier. Here, in the temple itself, a further surprise awaited him.

So tempted was Champollion to see the building, and so bright the moonlight, that the expedition members left the boats after a quick supper and set off across the fields in the dark, singing marches from the latest French and Italian operas, but found nothing after an hour and a half. Then they came across a raggedly impoverished local, ‘a walking mummy’ (wrote Champollion) who ran away as fast as he could, imagining them to be nomadic Bedouins in their hooded white burnouses, armed with guns, sabres and pistols. The fugitive was captured and proved to be an excellent guide. Reaching the temple, they were thrilled by its moonlit outline, which ‘united grace and majesty’, and even attempted to read some of the inscriptions by feeble torchlight. Returning to the boats at three o’clock in the morning, they were back again in the temple at seven.

Birds among papyrus plants at Beni-Hassan, from Rosellini’s Monumenti dell’Egitto e della Nubia.

(Wall painting from Beni-Hassan, from Rosellini’s Monumenti dell’Egitto e della Nubia, vol. 1, pl. VII.)

In the bright light of day, they quickly realized why they had been unable to read some of the inscriptions. Many of the intended cartouche inscriptions did not exist. They had not been erased, as often happened in Egypt when a former ruler was censored by a successor: the temple had actually been left unfinished by its patron. ‘Don’t laugh’, Champollion informed his brother – but the famous cartouche for ‘Autocrator’ was in fact empty of hieroglyphs: the signs must have been added by the artists working for Jomard, in the belief that the Egyptian Commission had forgotten to include the hieroglyphs in the original drawing, made around 1800. (Ironically, Denon’s drawings of Dendera in his book of Egyptian travels were accurate in this detail.) ‘That is called “offering the rod to be flogged”,’ Champollion joked about Jomard’s mistake. His own vaunted evidence for the age of the zodiac was now plainly a sham, as a consequence of the trust he had placed in the Description de l’Égypte. But he quickly concluded from the ‘decadent’ style and poor quality of the temple carving that its date must still be Greco-Roman, regardless of the (lack of) hieroglyphic evidence. Certainly, the Dendera temple and its zodiac had nothing whatsoever to do with the beginnings of Egyptian civilization, as had once been vociferously proposed.

View of the temple of Hath or at Dendera by Dominique Vivant Denon.

(Drawing of Dendera temple by Dominique Vivant Denon, c. 1802. British Museum, London.)

Much as he admired the architecture of the temple, if not its sculptural decoration, Champollion spent only a day or so at Dendera. Thebes – described in Homer’s Iliad as ‘Thebes of a Hundred Gates’, from each of which 200 warriors sallied with horses and chariots – now lay around a bend in the Nile. Late in the morning of 20 November, the wind picked up after a teasing lull and allowed the expedition to sail on to its long-awaited destination. Champollion’s fevered dreams of the palace of Karnak and the tombs of the Valley of the Kings were about to assume an astonishing reality.

‘Cleopatra’s Obelisk’ in Alexandria, painted by Dominique Vivant Denon in July 1798, soon after the arrival of the French expedition in Egypt.

(Searight Collection, London.)

The Franco-Tuscan expedition in Thebes, 1829, painted by Giuseppe Angelelli between 1834 and 1836. From left to right: (standing) Salvador Cherubini, Alessandro Ricci, Nestor L’Hôte and the dragoman interpreter; (behind this group, half-hidden) the artist Angelelli; (seated with hand on head) Giuseppe Raddi; (standing) François Lehoux; (reclining at front) Alexandre Duchesne; (standing, draped in white) Ippolito Rosellini, watched by his uncle Gaetano Rosellini; and (seated, with sword) Champollion.

(The Franco-Tuscan expedition to Egypt, painting by Giuseppe Angelelli, 1834–36. Archaeological Museum, Florence. Photo Scala Florence, courtesy of the Ministero Beni e Att. Culturali.)

A page from the manuscript of Champollion’s ‘Egyptian Grammar’, published in 1836.

(Folio 10 from the autograph manuscript of Champollion’s ‘Egyptian Grammar’. Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris.)

A page from one of Champollion’s notebooks.

(Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris.)

A bas-relief from Abu Simbel showing Ramesses II in a chariot, published in Champollion’s Monuments de l’Égypte et de la Nubie.

(Bas relief from the temple at Abu Simbel, from Champollion’s Monuments de l’Egypte et de la Nubie, 1835–45, pl. 15. Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris.)

Detail from a portrait of Champollion by Léon Cogniet, 1832 – the year of Champollion’s death.

(Musée du Louvre, Paris. Photo The Art Archive/Alamy.)