etween the ages of 5 and 18, kids spend eight hours a day, five days a week, nine-ish months a year stuck in a building that smells like microwavable pizza and industrial tile cleaner. Frankly, it’s tough to set a tween book anywhere else. But the sheer amount of time kids are legally required to be in school alone does not explain its incredible popularity as a YA setting. School also has all the ingredients necessary for a dramatic narrative baked right in: complex hierarchies, constant power struggles, being forced to interact with your enemies, and so on.

etween the ages of 5 and 18, kids spend eight hours a day, five days a week, nine-ish months a year stuck in a building that smells like microwavable pizza and industrial tile cleaner. Frankly, it’s tough to set a tween book anywhere else. But the sheer amount of time kids are legally required to be in school alone does not explain its incredible popularity as a YA setting. School also has all the ingredients necessary for a dramatic narrative baked right in: complex hierarchies, constant power struggles, being forced to interact with your enemies, and so on.

For an evergreen source of drama, school and schooling have changed a lot in the past century. In 1900, only about 50 percent of American children of any age, race, or gender were enrolled in any school, period, and African American children were far less likely to access schooling than their white peers. High schools only started to become common in the U.S. in the 1910s, and as late as 1940, less than half of Americans continued their formal education past the eighth grade. Different states instituted mandatory schooling at different times, and not until the 1950s were most American adolescents attending high school. Soon after that, school integration became a focus of the civil rights movement, and by the early ’70s, almost all Americans attended high school and around 80 percent of high schoolers were graduating.

Yet despite all the changes schooling underwent in the real world, many teen books about school in the 1980s are, surprisingly, strikingly similar to books about school from a hundred years earlier. In Elizabeth Williams Champney’s 1883 book Three Vassar Girls Abroad, which is widely considered to be the first school series for girls, the titular young ladies ran around having low-stakes, upper-middle-class, nonacademic adventures like old-timey Jessica and Elizabeth Wakefields (or, as the subtitle puts it, take “a vacation trip through France and Spain for amusement and instruction. With their haps and mishaps.” Haps!). The same goes for subsequent books like Margaret Warde’s Betty Wales, Freshman (1904), and Grace Harlowe’s Plebe Year at High School and The Merry Doings of the Oakdale Freshmen Girls, both by Jessie Flower and both published in 1910. As the ’80s and ’90s school series novels in the following chapter show, even after the social battles of the ’60s and ’70s, a wide swath of school-novel protagonists continued to engage in no deeper activities than some haps and mishaps.

YA books of the ’70s were often skeptical of school administrators (see: Paula Danziger’s 1974 book The Cat Ate My Gymsuit) or of entire schools (see: Robert Cormier’s The Chocolate War). In the school stories of the’80s, the opposite was true: school administrators just wanted what was best for students, and even if crappy stuff happened to them at school, it wasn’t really the school’s fault. School was essentially fun.

Case in point: Kate Kenyon’s Junior High series, published from 1986 to 1988, which reimagined the most emotionally hideous years of life as actually just kinda fun and silly. A typical Junior High heroine gave nerds makeovers, ran the school for the day, and traded families for the week, all while wearing “frilly white blouses that played up her peaches and cream complexion” and “trim khaki pants [that] showed off her trim figure.” Their problems ran similarly light; in book #4, How Dumb Can You Get?, heroine Nora claims to have experienced “one of the worst mornings of my life” because some kind of motorized egg beater she constructed for shop class broke down. My junior high experience involved mean girls telling me that I “smell like hot butt,” but you’re right, Nora, not being perfect in shop class is also a problem.

But such airiness may have been the point. Rather than tuning out the experiences of those of us who spent eighth grade weeping in a bathroom stall, Junior High might have been trying to help its readers—who, like almost all YA and middle grade readers, were younger than the protagonists in the books they read—feel less scared about making the jump to junior high.

Other school-focused series had more of a structural gimmick, like Linda A. Cooney’s Class of ’88 and Class of ’89 series. Each of these miniseries focused on a group of friends in a different high school class, and each book was named after a school year: Freshman, Sophomore, and so on. Though their title years and covers peg the books to a specific place and time (God bless that lemon-yellow sweater and button-down combo), the content is concerned with timeless issues like finding one’s place in life and one’s social circle, occasionally spiced up by mentions of ’80s-specific trappings like Rubik’s cubes or menacing punk rockers.

Yet other school series zoomed in, as it were, on a particular school pursuit, such as Marilyn Kaye’s Video High series, which ran for nine books from 1994 to 1995 and follows the chaos that ensues when students at the school’s TV channel are allowed to cover whatever their little 90201-addled-hearts desire, such as teen sex surveys, drugs, and more. In its quest to rebrand AV activities as hip and not at all geeky, Video High yields more questions than answers, such as, why are these teachers giving the kids free rein on making programming? Are they worried about Sweeps Week? Isn’t school TV supposed to cover forecasts and track-meet results? More to the point: who’d watch reports on drugs and sex surveys produced by a bunch of 17-year-olds? Wouldn’t everyone at school rather go home and watch professional programming instead of hysterical lo-fi messes created by people with vendettas against the prom queen?

The students in ’80s and ’90s school series were usually upper-middle-class WASP-y kids having mostly WASP-y problems at a public school. But some exceptions existed, like Leah Klein’s early 1990s series, the B.Y. Times. The protagonists are a group of girls who work on the school paper at an Orthodox Jewish school for girls (“B.Y.” stands for Bais Yaakov), and the series, which ran for at least eighteen volumes, became so successful as to have a spin-off series (the B.Y. Times Kid Sisters). There’s almost no record of the main series’ existence today, besides a 2015 tribute by writer (and former child actor) Mara Wilson on the now-defunct blog The Toast and some pricey copies available on eBay.

In some ways, the B.Y. Times can be seen as just another part of the parallel universe of religious pop culture knock-offs, like Veggie Tales or clean copies of Die Hard, in which Bruce Willis shouts “Yippee-ki-yay, Mr. Falcon!” But these books also point to the power of the formats and archetypes of girls’ series, combining classic ’80s problems about friendship stresses and school trouble with uniquely Orthodox Jewish predicaments like figuring out whether talking about others behind their backs is banned by the Torah or accidentally getting stuck in the middle of the Gulf War while visiting family in Israel(!!). But even though the group was in many ways the anti-BSC—as Wilson notes, “None of [the B.Y. Times heroines] ever talked about what they wanted to be when they grow up, other than mothers. All women were happy to have children and keep Shabbos. No one questioned authority.”—those archetypes carried enough weight to cross cultures.

Unlike their secular peers, the girls of the B.Y. Times cover illustrations wore clothes that were less ’80s wacky and more classic and modest, reflecting their Orthodox faith.

The era of kinder, gentler school lit didn’t mean that problems never went down within the walls of your local junior high. It just meant that they were, on the whole, dealt with in moderate ways, even when the problems themselves were kind of harsh.

Schools were ground zero in the book-banning wars of the early ’80s. Complaints made to the American Library Association about local communities prohibiting specific titles skyrocketed from 300 a year in the late ’70s to more than 1,000 a year in 1981. These literary cultural wars are the grist for Betty Miles’s 1980 coming-of-age novel Maudie and Me and the Dirty Book, in which Kate, an anxious 11-year-old conformist, learns the value of standing up for herself and her beliefs with an assist from classmate Maudie, a messy, spirited, emotionally vulnerable nonconformist. Yet it is Kate who ends up picking a so-called “dirty book” to read to a class of first-graders. (It’s a picture book about the birth of a puppy! Fetch my smelling salts!) This, of course, provokes the younger kids’ curiosity about where babies come from, which leads to small-town outrage and prompts a group called Parents United for Decency that wants to “keep filthy reading materials” away from kids to smear Kate as some kind of slatternly tween smut peddler. In timeless kid-lit fashion, Katie ultimately learns to be to herself and to ditch her Esprit-zombie pals in favor of the true-blue Maudie; but the book’s examination of the consequences of censorship make it unusually meta and more subversive than other books of the genre. (Whether or not Maudie was ever banned because of its unflattering portrayal of overzealous pearl-clutching parents has been lost to the ages.)

Unlike Kate, the heroine of Barthe DeClements’s 1985 book Sixth Grade Can Really Kill You, known as Bad Helen, is not an anxious conformist. She’s pretty much the Bart Simpson of her school, always ready to prank a teacher with a homemade trip wire or vent her frustrations via swift application of spray paint to school property. But Helen is no rebel sans cause; she acts out to deal with the stress of living with a learning disability, which her mother can’t quite admit is real. When this book was published, the ink had barely dried on legislation supporting public-school kids with learning disabilities (a term that had been coined only in 1963), so the sympathetic portrayal of Helen’s experience was relatively groundbreaking, although some parts feel thankfully outdated to the modern reader (including, I hope, the slur Helen’s classmates hurl at her). But Helen’s frustration, her mother’s reluctance to acknowledge the disability, and the life-changing support of Helen’s teacher still feel all too relevant.

A Kirkus review of Our Sixth Grade Sugar Babies gave a particular shout-out to its “engaging title and jacket” and called the book “thoughtful, well-crafted, and sure to be popular.”

What feels even more dated is the anti-pregnancy curricula that required kids to carry a sack of sugar, flour, or other baking ingredient around for the weekend in order to learn about the responsibility of caring for an infant. (Seriously. The Philadelphia Inquirer reported on schools using “egg babies” as early as 1986.) Vicki, the heroine of Eve Bunting’s 1992 book Our Sixth Grade Sugar Babies, loses her sugar sack when she’s busy checking out a cute boy, which may reveal the flaws inherent in the project: Is it really so easy to misplace a human baby, or to go to the grocery store and get a new baby? And do babies attract this many ants? These logical shortcomings are perhaps why the “raise a literal food baby” storyline is now only known as the one kind of sitcom plot less plausible than the “if we have to share a bedroom, we’re going to split it down the middle with a painted line” plot.

Most novels set at school dealt with problems that were fairly trivial— forgotten lunch money, pop quizzes, the latest gossip about who’s been banned for life from Pretzel Time. And that’s great; can you imagine how much harder childhood would have been if every night you had to complete your social studies reading and absorb a nuanced lesson about the folly of man? But some school novels, just like some schools themselves, did occasionally engage with big issues.

Although real-life class presidents usually clinched victory simply by promising the senior class a trip to Six Flags, in Lael Littke’s 1984 novel Trish for President every school government campaign has a manager who runs around yelling about strategy like James Carville commanding his war room, even though their strategy is rarely more complex than something you could’ve thought up on the bus ride to school. But Trish isn’t really about bloodthirsty high school elections; it’s about women in a small town at the dawn of the ’80s trying to figure out what to do with the vestiges of second-wave feminism. Trish is running for president because alleged mega-hunk Jordan is also running, and it initially seems like a good way to get his attention. But along the way to Election Day, Trish ponders whether “pushy” women are considered desirable by men, whether her homemaker mother is filled with regret about her career path not taken, and whether much has changed since her mom’s day, anyway. She muses: “One part of me wanted to get out and prove to…everybody else that I could face the world and fight those barracudas. Another part just wanted to cook dinner for Jordan every night.”

Trish never resolves her conundrum, which makes perfect sense. Littke’s book was published in 1984, the same year presidential candidate Walter Mondale picked Geraldine Ferraro as his running mate, making her the first woman on a major party ticket, and as the relative controversy of their pairing demonstrated, pretty much no one at that time could agree on how women fit in to politics. (Thank God we’ve got that one figured out now, right, guys? Guys?)

If few multi-book series dipped into big issues, fewer still organized themselves entirely around a single big issue. Operation: Save the Teacher from 1993 may be the only tween series ever to flow from the premise that a group of kids want to help a teacher who has just become widowed because his wife died in a car accident. Still, there’s something far more remarkable about Operation: Save the Teacher, namely that it was written by Meg Wolitzer, author of The Interestings and other award-winning books that do not have soft-focus oil paintings on their covers. Regardless, the good intentions of the Save the Teacher schoolkids are somewhat overshadowed, at least for a modern adult reader, by the utter bizarreness of their pursuit. Stop trying to save that teacher! Just let him drink in peace, kids.

A more sophisticated take on teens, school, and death can be found in Janet Quin-Harkin’s 1991 series Senior Year. As we learn from the cover of book #1: Homecoming Dance, “Kyle was gorgeous. Kyle was funny. Kyle was wild.” We soon learn that Kyle is also dead, the casualty of a tragic drunk driving accident. While he was alive, he formed close emotional relationships with four girls from different cliques, who now happen to all be on the same school dance decorating committee cum grief support group (“I guess Kyle was really good at hiding his real self from people,” one of them remarks, in what had started as a discussion of the dance’s “undersea fantasy” theme). This connection is the core of the four-book miniseries; each volume flashes back to Kyle and his relationship with a specific girl, revealing more about her life as well as Kyle’s unwitting march to doom. For example, in this first volume, we learn both that Joanie’s exciting summer makeover made her more popular while straining her relationship with her best friend Brooke, and that Kyle thinks that driving after having four beers is no big deal. Senior Year feels less of a piece with other YA series than like an update of the Shangri-Las’ “Leader of the Pack” for the 90210 generation. The shadow of Kyle’s impending death lends gravitas to classic YA concerns like getting on prom court and figuring out whether or not a specific hunk is “out of your league,” while also pointing out classic YA concerns are pretty low stakes compared to, you know, death.

Speaking of the unexpectedly grim: if you think, based on the title, that Jenny Davis’s 1988 book Sex Education is a goofy teen sex romp, you would get an F. Narrator Olivia quickly and very frankly corrects that misconception in the beginning, stating, “I am sixteen years old. I am writing this at my desk in my room on the ninth floor of the University Psychiatric Hospital.” In flashback, we see Olivia become friends with David after they are partnered up in an unorthodox ninth-grade sex-ed class. Assigned to “care for” someone, they pick Maggie, a fragile young pregnant woman who recently moved to the neighborhood with her husband. Olivia and David proceed to fall in (ninth-grade) love; Olivia explains, “Mrs. Fulton once asked our class did we think holding hands was a sexual act. A lot of kids sneered, but I knew better. I knew the answer to that one. It could be. It depended on who you held hands with, and how.” But this warm fuzziness is short-lived. It turns out that Maggie is troubled because her husband is physically abusing her, and when David and Olivia try to get Maggie and her new baby to safety, Maggie’s husband pushes David down the front stairs, killing him instantly. Olivia becomes catatonically depressed for six months, Maggie refuses to testify against her husband, and he’s out of jail before a year is up. It’s infinitely bleaker than Meatballs—and way better.

This cover for Sex Education is unusually abstract for a mass-market ’80s YA novel—rare was the illustration that didn’t portray the characters in a photorealistic style—and the taglines leave no doubt as to its gravitas (get your lessons! Get your loving and caring!), stressing more the “education” than the “sex” part.

But how exactly does one package such an infinitely bleak YA novel? In this case, the answer is multiple covers, although neither proved particularly effective at representing the book’s content. The book’s original cover (see this page) looks kind of like the logo for the Good Vibrations sex toy company, or possibly a body lotion from the ’80s; a later cover (at left), designed to look like a school binder, features a classic illustration of two kids at a desk. Neither approach quite manages to both stay true to the book and appeal to the post-BSC sophisticate; from a marketing perspective, it seems as though the publisher couldn’t decide whether to shelve this title in the now-retro problem novel territory or lean on the titillating title and gloss it up to look like its contemporaries, the actual story notwithstanding. This identity crisis might be why this great, albeit dark, book seems to have been undeservedly lost down the teen fiction memory hole.

The ’80s YA fascination with wealth seeped into school lit, producing a boomlet of books set in boarding schools—like regular schools, except for rich people! Unlike more classic boarding school novels like The Catcher in the Rye and A Separate Peace, these books weren’t about unsupervised teens fumbling their way towards adulthood and occasionally pushing each other out of trees—in fact, the most famous boarding school series, the Girls of Canby Hall, is right at home with its BFF-driven contemporaries. The 33-book series, which debuted in 1984 and was written by the pseudonymous Emily Chase, tells the story of three roommates at a fancy-schmancy New England boarding school as they weather the hijinks, boy problems, and occasional kidnappings of your typical ’80s YA series. Shelley, Faith, and Dana, the original Canby girls (they were replaced mid-series by a new class of students), were brainier than the average Wildfire heroine and more down-to-earth than any Wakefield, but their adventures generally failed to defy girls’ series convention.

Still, in an era when YA bookshelves were a field of white faces, one of the series’ primary heroines, Faith, was an African American girl (a full two years before Claudia Kishi would emerge on the scene). Moreover, the books immediately engage with the racial tension that Faith encounters at a predominantly white school. After white farm girl Shelley makes an ignorantly racist remark, Faith is rightfully pissed off, but, as writer and critic Mindy Hung has argued, the conflict is not handled particularly sensitively; the racist particulars are buffed out when all three roommates end up feuding over the remark. Missteps aside, having a heroine of color discuss racism in a light series YA novel was still a big deal—especially because Faith didn’t exist solely to teach everyone about the realities of racism. She’s a regular, silly teenage girl who befriends both of her roommates and ends up helping Dana prank her ex-boyfriend by the end of the first book. She was a full YA character—and that fullness included her experience of life in a racist society.

Of course, not all boarding school series were so thoughtful. Sharon Dennis Wyeth’s Pen Pals series, which ran for 20 volumes from 1989 to 1991, focused on a foursome of schoolmates—Amy, Palmer, Lisa, and Shannon—who spend a lot of time writing to their male pen pals, while occasionally making time for other pursuits, like listening to Joan Jett or bragging about eating lobster. This was a rather paper-thin premise, but after the Great Middle Grade and YA Club-splosion, what clubs were even left? We could have very easily ended up with a series about a whittling society or (God forbid) Model U.N. In this case, the boarding school was just another layer of clubbiness that attempted to distinguish the series from its zillions of competitors.

The cover of Pen Pals #1 makes no visual reference to its boarding school setting and instead leans heavily on the letter-writing angle (and funky outfits).

Like any precocious teen, the YA series was eager to enter the “real world” of college. Yet YA protagonists were hardly more mature than the average high schooler; a campus setting merely implied that there would be more “adult” stuff (aka sex and maybe drinking) side-by-side with the infantile tantrums and short-sighted thinking that made these series such delights to begin with. For example, Joanna Wharton’s Campus Fever series, which ran from 1985 to 1986, didn’t cover existential depression or student-loan horrors. Instead, the eight books introduced themes like sex and attempted suicide to the standard ’80s YA series. And when the Wakefield twins made an exodus from Ned and Alice’s house to Sweet Valley University in 1993, little changed except that characters were suddenly able to guzzle booze to deal with their endless self-created personal problems. (Also, Jessica and Lila get married briefly to random dudes, but they both would have absolutely done so in high school had they been able, so it barely counts.)

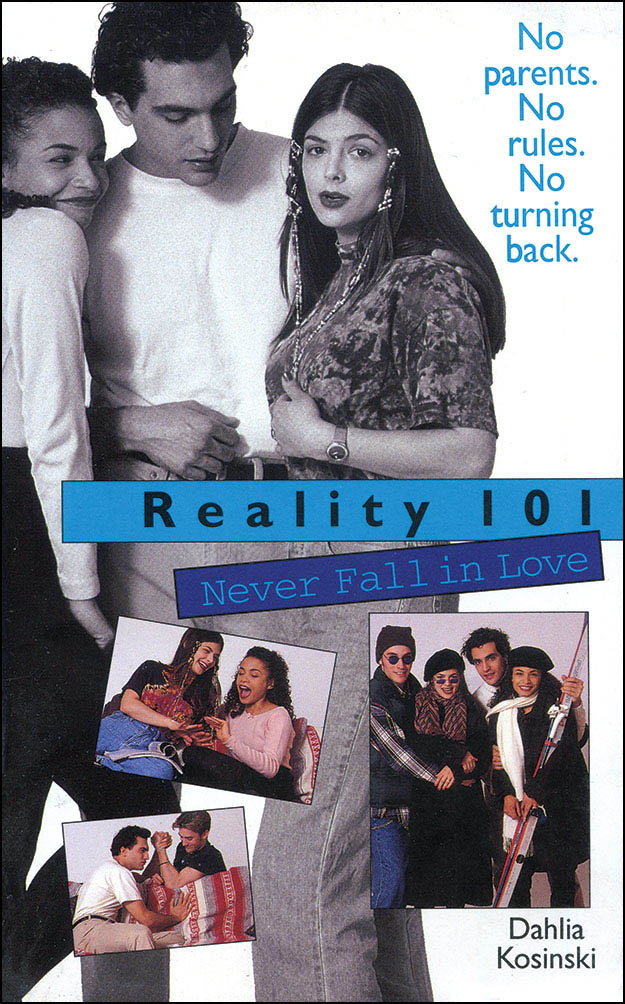

In addition to awkward sex scenes, college YA also promised more problems per square inch, not least because the characters’ parents aren’t there to save them. This was the premise of Dahlia Kosinski’s Reality 101 series; one cover’s tag line read, “No parents. No rules. No turning back.” (That cover also nixed ’80s gauzy pastel paintings in favor of 90210-evoking photos that seem to scream, “There will be sexual relations in this book!”) The series, which lasted only two volumes published in 1995 and 1996, chronicled the lives of six sexy coeds sharing a house in Boulder, Colorado, that, judging from the cover, was located inside a Sprite ad. Characters hook up with one roommate after telling another roommate that they never hook up with roommates, or crash their car because they started drinking at 7 a.m., or make out with their gross-sounding boss and then are forced to model nude in the figure-drawing class that his wife teaches. You know, college stuff!

None of these college novels accurately renders the experience of attending college, but that was hardly the point. Seeing as the readers were nervous middle-and high-schoolers, these series were a soothing(ish) promise that college is less about leaving home for the unknown and more about reliving high school, except now you can have boys in your room! (Which of course is a lie, but so is most of what you learn in high school.)