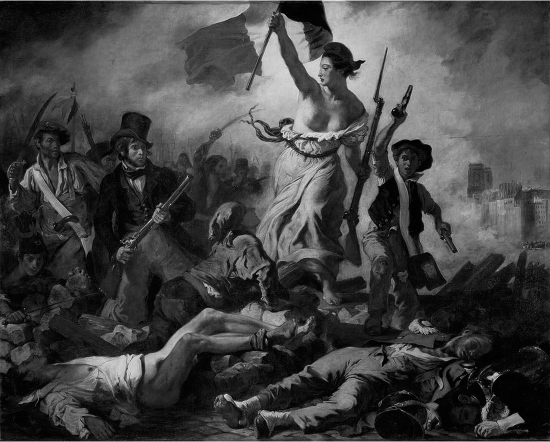

Figure 2.1 Liberty Leading the People. Eugène Delacroix [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

We now have a broad picture of the historical phenomenon known as “mass society” in its different manifestations: political, demographic, social and cultural. In this chapter the goal will be to describe the resistance to massification, surveying the criticisms and anxieties to which it gave rise. Here, too, the criticisms will be divided into subsections: politics, demographics, society and culture. The theme that will take center stage in the next chapters, the fascist response to the mass, will not be dealt with here. The period covered will be, roughly, from the mid 19th century to the verge of the First World War. On a few occasions, when this will be necessary, events will be discussed from outside this timeframe. Geographically, we remain in Europe, with occasional visits to the United States, the most important overseas Western country. Since mass society is a pan-European phenomenon, no distinction will be drawn at this stage between countries that will subsequently turn fascist (Italy, Germany) and countries that will maintain their parliamentary democracy (England, France—the latter succumbing to an authoritarian regime only with military defeat and occupation). This does not mean that this important difference has been forgotten, yet for the time being the focus will be on processes jointly experienced by Western European countries, under the assumption that fascism is a political and ideological plant that grows on European soil everywhere, even if it bears fruit only in certain countries, offering a particularly favorable climate.

The gradual extension of the franchise and the demand of the masses to participate in political life triggered deep fears among the élites and the middle classes. The result was the blossoming of a fierce anti-democratic polemic, admonishing against the insidious implications of mass rule. Already in the 19th century, and as limited as the political enfranchisement of the masses was, critics of democracy glimpsed in it a fundamental threat to all the goods of civilization: social order, the rule of law, hierarchy, private property, culture and so on and so forth. The masses were seen as a force subverting all that, leaving anarchy, disobedience, and cultural decline in their trail.

At the root of the fear was the acknowledgment that, for all their cultural, spiritual and intellectual inferiority, there was one advantage enjoyed by the masses, which democracy converted into a lethal weapon: their quantitative superiority. This led to one of the most common tropes of the opposition to mass politics, i.e., the claim that democracy displaces “quality” and brings “quantity” to the fore, relying on the arbitrary advantage of “numbers,” whereas worthy rule reflects qualitative stature.

Such reproaches were by no means the exclusive fare of die-hard conservatives rebuffing all reform. Many liberals regarded the triumph of the masses as the triumph of quantity—the very term “mass” in many different European languages of course designates a clear quantitative criterion. And so, the English liberal Robert Lowe, who held several important offices under W.E. Gladstone in various governments (Chancellor of the Exchequer, Home Secretary), strictly opposed the extension of the franchise demanded by the Conservative Disraeli, and during the campaign surrounding the proposed reform of 1867 gave several passionate speeches warning against democracy. In one of them he defined this political system as “a right existing in the individual as opposed to general expediency … numbers as against wealth and intellect” (Hansard July 15, 1867: 1540). He further admonished against the democratic empowering of the trade unions:

It was only necessary that you should give them the franchise, to make those trades unions the most dangerous political agencies that could be conceived; because they were in the hands, not of individual members, but of designing men, able to launch them in solid mass against the institutions of the country.

(1546)

Lowe concluded his speech (1549–50) with an apocalyptic vision according to which the extension of the franchise signifies nothing less than the terminal decline of English civilization:

Sir, I was looking to-day at the head of the lion which was sculptured in Greece during her last agony after the battle of Chaeronea [a 338 BC battle in which the Greek were defeated by the Macedonians], to commemorate that event, and I admired the power and the spirit which portrayed in the face of that noble beast the rage, the disappointment, and the scorn of a perishing nation and of a down-trodden civilization, and I said to myself, “O for an orator, O for an historian, O for a poet, who would do the same thing for us!” We also have had our battle of Chaeronea; we too have had our dishonest victory. That England, that was wont to conquer other nations, has now gained a shameful victory over herself; and oh! that a man would rise in order that he might set forth in words that could not die, the shame, the rage, the scorn, the indignation, and the despair with which this measure is viewed by every cultivated Englishman who is not a slave to the trammels of party, or who is not dazzled by the glare of a temporary and ignoble success!

In their clamor to contain the political rise of the mass, critics of democracy often embraced positions that anticipate, in part, the fascist vision. This was the case of the Scottish social critic Thomas Carlyle, one of the most influential writers of the Victorian period. Carlyle illustrates the fact that the difficulty in coming to terms with mass society yielded authoritarian conclusions not only in countries with relatively young and unstable liberal and parliamentary traditions, such as Italy and Germany, but in Britain, the liberal political milieu par excellence. This, in turn, underscores the need to understand fascism in a wide European context. In the first decades of his intellectual career Carlyle gained a reputation as an acerbic critic of modern Britain, which he portrayed as narrow-minded, materialistic and greedy. He lashed out against what he termed mammonism and the laissez-faire that subordinated all social procedures to the whims of the market, draining modern life of its moral and spiritual content, abusing the poor and instilling them with social resentment, driving a wedge between them and the upper classes and thus sowing the seeds of revolt. These attacks on capitalism and its underlying economic doctrine, that he called “the dismal science,” might create the impression that the Sage of Chelsea was a man of the left. Yet what truly concerned him in reality was not the suffering of the vulnerable members of society as much as the pit that unrestrained capitalism was unwittingly digging for itself, its short-term quest for profit at all costs endangering the long-term stability of the class system. Exploitation he deemed natural and inevitable in any healthy society, yet too much of it, or an exploitation that was too naked and unembarrassed, will endanger capitalism. At the same time, Carlyle faulted laissez-faire less for its ruthlessness and more for the leniency he attributed to it. Politically, capitalism emancipates the worker, basing his labor on a strictly voluntary and contractual agreement. Unlike past epochs, the worker is under no extra-economic obligation to his employer, and both seek each other out of sheer self interest. Yet this was too flimsy a basis on which to found an enduring society. Class inequality cannot remain economic only but must be anchored legally, politically and ethically; hence his support for the “permanent contract” of slavery over the “nomadic contract” of liberal modernity. This explains Carlyle’s ultraist rejection of mass politics, of political liberalism, democracy and socialism. He saw them as myopic and sentimental, rushing headlong to free the slaves without recognizing the acute dangers this entailed for the entire social order. Already in 1849, during a public campaign to improve the living and working conditions of the black plantation workers in the West Indies, then partly under British control, he defended slavery as a natural system, well suited to extract from the worker the labor he owed to society:

[W]ith regard to the West Indies, it may be laid down as a principle, which no eloquence in Exeter Hall, or Westminster Hall, or elsewhere, can invalidate or hide, [t]hat no Black man who will not work according to what ability the gods have given him for working, has the smallest right to eat pumpkin, or to any fraction of land that will grow pumpkin, however plentiful such land may be; but has an indisputable and perpetual right to be compelled, by the real proprietors of said land, to do competent work for his living. This is the everlasting duty of all men, black or white, who are born into this world.

(Carlyle 1869a: 299)

Some 20 years later, Carlyle naturally became one of the most stringent critics of the 1867 reform, who many regarded as the triumph of democracy in Britain. He fully shared Robert Lowe’s bleak view of democracy as the twilight of civilization, and held that the only way to prevent this outcome is to enact a counter move that will restitute proper order. In a famous polemic treatise against the reform, he repeated the assertion that the abolition of slavery, that is of the political subordination of the workers, necessarily ushers in socialism or revolution:

One always rather likes the Nigger […]. The Almighty Maker has appointed him to be a Servant. […] The whole world rises in shrieks against you, on hearing of such a thing:—yet the whole world […] listens, year after year, for above a generation back, to “disastrous strikes,” “merciless lockouts” and other details of the nomadic scheme of servitude; nay is becoming thoroughly disquieted about its own too lofty-minded flunkeys, mutinous maid-servants […] and the kindred phenomena on every hand: but it will be long before the fool of a world open its eyes to the taproot of all that, to the fond notion, in short, That servantship and mastership, on the nomadic principle, was ever, or will ever be, except for brief periods, possible among human creatures.

(Carlyle 1867: 5–6)

While capitalism, for its own good, needs to somewhat moderate its exploitative ways, the political solution to the democratic slide is the reinstatement of a neo-aristocratic rule where the many are governed by the few. “Democracy,” he claimed (1869b: 74) “may be natural for our Europe at present; but cannot be the ultimatum of it. Not towards the impossibility, ‘self-government’ of a multitude by a multitude; but towards some possibility, government by the wisest, does bewildered Europe struggle.” Carlyle’s diagnosis of the modern political conundrum led him to advocate stances that many have retroactively regarded as proto-fascist. “Carlyle,” wrote one scholar, “appears to be a violent conservative, or, as some have argued, virtually a fascist. That some aspects of his political position are similar to fascism is beyond dispute” (Abrams 1986: 943). Carlyle goaded the chosen few, the champions of order, and summoned their courage before the decisive clash against the masses, the carriers of anarchy. He was confident that in spite of their numerical disadvantage, the élite will prevail:

For everywhere in this Universe,[….] Anti-Anarchy is silently on the increase, at all moments: Anarchy not, but contrariwise; having the whole Universe forever set against it; pushing it slowly, at all moments, towards suicide and annihilation. To Anarchy, however million-headed, there is no victory possible. Patience, silence, diligence, ye chosen of the world!

(Carlyle 1867: 50)

The invoked “chosen of the world” would come, Carlyle hoped, out of a union between the traditional nobility and the middle-class, the industrial heroes of the present. They will close their ranks and defeat the millions of the rabble. He envisaged a militarization of social life, wanting to mold society and economy after a military fashion, as attested to by his expression “the captains of industry.”1 Carlyle, it is interesting to note, was an admirer of German culture and tradition, which he saw as a wholesome alternative to the crass materialism infecting England. He popularized in Britain the tenets of German idealism—heavily filtered through his own cult of heroes—as expressed in the works of J.G. Fichte, Schiller and Goethe, and equally praised the German, particularly Prussian, political tradition, where he identified the military and heroic nobility so dear to his heart: in 1858 he published the biography of Friedrich “the Great.” His writings, in turn, were highly appreciated in Germany and influenced intellectual developments there during the second half of the 19th century. And while Nietzsche liked to ridicule the Scottish writer’s style and ideas, a close reading of his own texts reveals unmistakable Carlylean traces, especially in what concerns the social and political dimension of his thought.2

One might argue that Carlyle’s extreme critique of democracy is unrepresentative of the age’s Zeitgeist, at least within the moderate British context. This is true to an extent, but Carlyle’s exceptionality should not be overstated. Few in Britain went as far as he did, for instance on the issue of reverting to feudal labor relations, but many shared his basic fear that mass democracy poses a serious social threat, unless a way is found to significantly constrain and dilute it. The position of the liberal Lowe was already mentioned. And there are many other cases. One of them is Matthew Arnold, who like Carlyle was an eminent Victorian social critic, with a long-term impact on 20th-century conservatives and mass critics such as Ortega y Gasset and T.S. Eliot. (See Femia 2001: 136.)

Arnold, formerly engaged in literary writing, began in the early 1860s to publish a series of essays reflecting on the significance of the move to a more democratic regime. His most famous and important book, Culture and Anarchy, was written in 1867–69, accompanying the reform of the franchise. These writings express the conviction, close to Carlyle’s view, that culture is presently retreating before anarchy, and that the former must be protected from the latter. Democracy was typically seen as the victory of quantity over quality, of the indistinct collective over the talented individual. The English, he claimed in an 1861 essay titled “Democracy,” are historically an aristocratic and competitive nation, relying for their advance on the triumph of the best competitors. All this is jeopardized by the democratic, mediocre ideal, which strives toward joint action and the narrowing of gaps at the expense of national greatness:

Democracy is a force in which the concert of a great number of men makes up for the weakness of each man taken by himself; democracy accepts a certain relative rise in their condition, obtainable by this concert for a great number, as something desirable in itself, because though this is undoubtedly far below grandeur, it is yet a good deal above insignificance. A very strong, self-reliant people, neither easily learns to act in concert, nor easily brings itself to regard any middling good, any good short of the best, as an object ardently to be coveted and striven for. It keeps its eyes on the grand prizes, and these are to be won only by distancing competitors, by getting before one’s comrades, by succeeding all by one’s self; and so long as a people works thus individually, it does not work democratically. The English people has all the qualities which dispose a people to work individually; may it never lose them! [….] But the English people is no longer so entirely ruled by them as not to show visible beginnings of democratic action; it becomes more and more sensible to the irresistible seduction of democratic ideas, promising to each individual of the multitude increased self-respect and expansion with the increased importance and authority of the multitude to which he belongs, with the diminished preponderance of the aristocratic class above him.

(Arnold 1993: 10)

Arnold was no sworn elitist. He took to task all classes in England of his day and affixed them with unflattering epithets. The nobility he called “barbarians,” members of the middle class he referred to as “philistines,” a term he made popular in the English language, and the working class he disparaged as “populace.” This creates the impression, which Arnold certainly wanted to nurture, that he was an impartial observer standing beside the classes, committed to none of the great social camps. Central to his teaching was the stress on the need to overcome social divisions and form policies serving the nation as a whole. Yet this objectivity claim does not withstand a closer scrutiny of his works, which reveals that of the three great social classes he mostly feared the last one, the populace, chastising the other two fundamentally for failing to contain the mass and integrate it in the nation, as a result of both their weakness and their corruption. That working-class empowerment was the development truly disquieting him, emerges clearly from the following sentences:

This is the old story of our system of checks and every Englishman doing as he likes, which we have already seen to have been convenient enough so long as there were only the Barbarians and the Philistines to do what they liked, but to be getting inconvenient, and productive of anarchy, now that the Populace wants to do what it likes too.

(Arnold 1993: 120)

Arnold’s descriptions of the working class are suffused with fears of their new and bold political demands, and recoil from their crude and aggressive demeanor. Compared to Carlyle’s prophetic tone, and his quasi biblical, fiery language, Arnold cuts a relatively moderate figure, much closer to the political center. Next to the Scot, his style is dry and cautious, he often takes care to qualify his assertions and in general appeals more to his readers’ logic than to their emotions. Arnold’s name is therefore not mentioned in any genealogy of proto-fascism, and rightly so. It is therefore interesting to observe how even he, confronted with mass society, looks to authoritarian solutions. Central to his political doctrine is the recurring insistence that the time has come to moderate the moderation characteristic of English political culture and to embrace, however selectively, less permissive models of government, used by other countries. Passing through his political writings like a crimson thread is the call for the English to conquer their instinctive aversion to the state and realize that without a strong state, capable of assuming the tasks of social containment and molding, impending anarchy will not be halted. Arnold believed that the English middle class must educate the populace, shape and direct it, yet without state action it will find it difficult to do so, narrow-minded as it is (Arnold 1993: 22). Instructively, in presenting the state as a supra-class body that can conciliate the classes and bind them into a harmonious nation, Arnold (88) employs a term that will become pivotal in the fascist discourse, namely the corporate state:

[The workman] is just asserting his personal liberty a little, going where he likes, bawling as he likes, hustling as he likes. Just as the rest of us,—as the country squires in the aristocratic class, as the political dissenters in the middle class,—he has no idea of a State, of the nation in its collective and corporate character controlling, as government, the free swing of this or that one of its members in the name of the higher reason of all of them, his own as well as that of others.

Was Arnold willing to contemplate the use of force and coercion for attaining the so desired social peace? In principle, he makes clear that coercion is not legitimate and recommends in its stead the unifying force of a common culture, spiritual and above interests, a “harmony of ideas,” as the glue that will connect all social “organs.” Yet a more belligerent stance occasionally comes forward, since culture and ideas may not always suffice. He thus points to the supposed passivity of the forces of order facing demonstrators and rioters—the immediate background for this was the rioting of protesters in Hyde Park in 1867, clamoring for an extension of the franchise. He decries the way the working class, “our playful giant,” the representative bar none of modern anarchy, takes full advantage of the leniency of the liberal system, screams, riots, breaks and devastates as he wills, while the forces of order remain complacent. The “outbreaks of rowdyism tend to become less and less of trifles,” he observes (85), while “our educated and intelligent classes remain in their majestic repose, and somehow or other, whatever happens, their overwhelming strength, like our military force in riots, never does act.” It is thus not completely surprising that Arnold exhibits a marked admiration for countries on the continent whose government is central and authoritarian, such as Prussia (117–18), or France under Napoleon III and advises liberal England to take a leaf out of their book. “The growing power in Europe is democracy,” he writes in 1861, “and France has organized democracy with a certain indisputable grandeur and success.” “Being an Englishman,” he adds a little later (13), “I see nothing but good in freely recognizing the coherence, rationality, and efficaciousness which characterize the strong State-action of France.” Carlyle seems not so far removed, after all; in stopping the playful but anarchic giant, harmonic national ideas are indispensable, but so is military force.

The profound fear caused by mass democracy is the ground on which flourishes the different theories of the élite, which will eventually be enshrined at the heart of fascist ideology, in Italy, Germany and elsewhere.3 The three main proponents of this theory, regularly mentioned in the scholarly literature, are two Italians, Vilfredo Pareto—who introduced the term “élite” into the sociological discourse—and Gaetano Mosca, and one German, who lived mostly in Italy and Switzerland, Robert Michels. Minor differences between their theories notwithstanding, all three regarded democracy as impossible since the people or the mass cannot rule but always only small minorities, élites. Mosca and Pareto saw this positively, since for them mass rule was not only impossible but undesirable. They sharply attacked the mass for its purported irrationality and recklessness, while Michels regretted this insight: at least to begin with he saw in democracy an ideal worth striving for, yet with time he reached the pessimistic conclusion that genuine democracy can never be established since every organization, no matter how democratic it might be in its intentions and ideology, is bound sooner or later to develop an authoritarian structure where an élite takes command, whether this happens for all to see or behind the scenes. This was conceived by Michels as a true sociological inevitability, which he termed “the iron law of oligarchy.” As observed in Chapter 1, the theories of Pareto and Mosca exhibit a peculiar paradox: they sharply attack the rule of the masses at the same time that they claim that it is impossible. The danger of the masses is in its irrational onslaught on the laws of the capitalist economy, which for both sociologists are the laws of nature itself. As proclaimed by Pareto (1966: 122), “Above, far above, the prejudices and passions of men soar the laws of nature. Eternal and immutable they are the expression of the creative power; they represent what is, what must be, what otherwise could not be.” If, however, democracy is ruled out by nature itself, why write entire books to dismiss it? If the monster is just a bogeyman, why guard against it? And if the rule of the élites is indeed a sociological given, why invest so much energy in recommending it? Certainly, both writers see a great difference between different variants of élites. Élites they may all be, but some among them are painfully susceptible to democratic pressures. As a consternated Mosca (1939: 478–481) observed:

The ruling classes in a number of European countries were stupid enough and cowardly enough to accept the eight-hour day after the World War, when the nations had been terribly impoverished and it was urgent to intensify labor and production. […] Slave to its own preconceptions, therefore, the European bourgeoisie has fought socialism all along with its right hand tied and its left hand far from free. […] A powerful labor union or, a fortiori, a league of labor unions can impose its will upon the state.

One of Pareto’s central and most famous ideas concerned the circulation of élites, the thesis that history follows a circular pattern in which one ruling minority displaces another, and is displaced by a new ruling group in its turn. Among these élites he distinguished two main types, a lion-like, aristocratic élite, ruling via men and classes that are majestic, strong, determined and inflexible; and élites that resemble foxes, and rule with cunning, sophistication, smooth-talk and adaptability. Historically, the latter kind characterizes the period of bourgeois, liberal rule, which governs by coalitions and alliances, accommodates the popular classes and tries to cajole the masses. What is mistakenly called “democracy” is therefore not the rule of the people, but that of an élite of foxes flattering the masses that as a result become ever more impudent in their demands and infringe with impunity the law of the liberal economy, defying their employers and the—spineless—rulers. Once the situation becomes intolerable, the lions make a comeback, brushing aside the foxes and re-yoking the familiar, over-playful giant. In the context in which Pareto was writing, the reign of foxes is a clear allusion to the government of the liberal Giovanni Giolitti, who ruled Italy almost uninterruptedly in the years 1901–14, mediating between the industrialists and the socialists, interfering in the economy on behalf of the workers, and thus further abetting mass impertinence. Pareto predicted that the lions will sooner or later have to rescue Italy from the engorged mass trolls fed by the liberal élite, and when Mussolini’s troops marched on Rome in October 1922 the old Pareto, according to one account, rose from his sickbed and declared: “I told you so!” (In Livingston 1935: xvii).

With Mosca and Pareto we are already on the threshold of fascism, and they are commonly regarded as key figures in the evolution of the fascist worldview. Yet the conclusion should be avoided that their élite theories, alongside that of Michels, reflect the backward or otherwise unique attributes of Italy and Germany, as compared with the classical liberal countries. Pareto’s political and economic role model was always the liberal English one, and he highly esteemed the Swiss one as well. If he saw political liberalism as betraying economic liberalism, and hence yearned for the coming of the rescuing lion, this was not fundamentally so unlike Carlyle or Arnold wishing for England to move in an authoritarian direction in order to put a stop to mass unruliness. Or consider the following polemic against mass democracy by the English liberal Henry Maine, which might have been copied down from Pareto’s doctrines were it not for the fact that it preceded them. This is from 1885:

History is a sound aristocrat. […] [T]he progress of mankind has hitherto been effected by the rise and fall of aristocracies, by the formation of one aristocracy within another, or by the succession of one aristocracy to another. There have been so-called democracies, which have rendered services beyond price to civilisation, but they were only peculiar forms of aristocracy.

(Maine 1909: 42)

Maine also partakes of the ambiguity of his Italian counterparts with regards to whether democracy is real or nominal. Like them, he reassures his readers (29–30) who identify with the élite—and discourages those who do not—that democracy can never mean more than the façade of popular rule, since behind the scenes the professional “wire-puller” always prevails, moving the masses like marionettes. Yet this confidence is shallow, and just a few pages later (38; emphases added) Maine concedes the real political power of the mass:

The relation of political leaders to political followers seems to me to be undergoing a twofold change. The leaders may be as able and eloquent as ever, […] but they are manifestly listening nervously at one end of a speaking-tube which receives at its other end the suggestions of a lower intelligence. On the other hand, the followers, who are really the rulers, are manifestly becoming impatient of the hesitations of their nominal chiefs, and the wrangling of their representatives.4

One of the critical quandaries the élites were facing in an age of unfolding mass democracy was the frequent reluctance on the part of the masses to be absorbed into “the nation,” conceived of as a hierarchic working and fighting unit under the leadership of the bourgeoisie. If this was a thorn in the flesh of British nationalists such as Arnold or Carlyle, who were exasperated by the ever growing assertiveness of the populace, the problem was all the more vexing in newly established countries such as Italy, where national traditions and a collective sense of identity were far less developed than in England or France. The euphoria of the eventual political triumph of the Risorgimento, led by the middle classes in the face of frequent aristocratic hostility and widespread popular indifference, soon gave way to dismay at the masses’ perceived lack of gratitude for the heroic efforts of the bourgeoisie on their behalf, and lack of comprehension for the national mission, which was to cement and aggrandize Italy’s standing and reputation among the nations. The new ruling élite of post-unification Italy, composed predominantly of Piedmontese liberals, counted on the masses of the peasantry as foot-soldiers in the cause of the national revolution but was by no means eager to see them as equal political partners. As observed by Jonathan Dunnage (2002: 4–5):

Because of their frequent mobilization in the cause of counter-revolution, the fathers of the Risorgimento mistrusted the masses to the extent that […] they were reluctant to concede power to them. Even figures like Giuseppe Mazzini […] belonged to an enlightened middle class and aristocratic élite that was not prepared to overturn economic injustice or consider redistribution of land.

This situation meant that many liberals who had begun as radicals and revolutionaries, when it was a matter of terminating foreign rule in Italy, eventually transmogrified into conservatives and even outright reactionaries, when it was a matter of stemming internal opposition to their own rule in the post-unification era. A notable example of this trend was the right-wing hardliner Francesco Crispi, prime minister during the late 1880s and then throughout most of the 1890s, a strongman whose policies of internal repression and external adventurism earned him a reputation as a precursor of Mussolini, but who actually started as a fervent democratic patriot alongside Giuseppe Garibaldi. “During the 1860s,” writes Dunnage (2002: 5), “the rule of the Liberal Right (Destra Storica) often appeared to take on the characteristics of a dictatorship rather than a politically enlightened power.” This rule derived its popular mandate from an electorate that in 1870 was restricted to just 2 percent of the population, and relied on police and criminal codes largely adopted from the times of the ancien régime and the Napoleonic occupation.

Liberal rule in Italy generally catered to the interests of the industrial north of the country, advancing policies which, either by design or miscomprehension of the realities of the Mezzogiorno—the southern parts of the country—could not resolve the socioeconomic disparities geographically dividing the peninsula. This meant that popular alienation in the South towards the national project could never be truly surmounted. During the 1860s, especially, a traumatic gap opened up between the liberal élite and the Southern peasant masses, a wound that subsequently proved nearly impossible to heal. The liberals meted out severe punishment to Southern “brigands,” who were often discontented peasants who could not see how Italy’s rulers better served their interests than former local élites with whom they had developed complex interdependencies for decades, at least. In suppressing social disorder in the South, observes Giuseppe Finaldi (2012: 53), “far more ‘Italians’ were killed than all the heroic dead who had lain down their life for the ideals of the Risorgimento,” the number of the dead estimated at “several tens of thousands.”

But “the social question” was not merely a Southern one; the Italian masses in general responded lukewarmly to a country that would have them serve it, as workers, soldiers and tax-payers, but largely deprive them of political rights. While the Liberal left—Sinistra storica—has proven more attentive to popular grievances and sought to nationally incorporate the masses via piecemeal reforms and gradual extension of the franchise, its Trasformismo policies, too, were less than wholly successful. The Italian masses had, and were in the process of developing, strong allegiances to alternative, non-national identification loci, notably Catholicism and its political ramifications and then, slowly but surely, also socialism and other variants of radical politics.5 The Liberal order could never emerge as a truly legitimate representative of the people, either being too repressive, in its right-wing variant, or too corrupt, in its left-wing incarnation, that seemed to be offering a tepid, second best alternative, to the genuinely autonomous popular parties.

The state hoped to nationalize the masses by massive spread of patriotic propaganda, whose goal was to produce hard-working, hard-fighting and self-sacrificing Italians. The type of ethos propagated by the liberal élite could be exemplified by a passage from Edmondo De Amicis’s 1886 best-selling pedagogic book, Cuore, where a father explains to his son his love for Italy (De Amicis 1915: 100–101):

Why do I love Italy? Do not a hundred answers present themselves to you on the instant? I love Italy because my mother is an Italian; because the blood that flows in my veins is Italian; because […] all that I see, that I love, that I study, that I admire, is Italian. Oh, you cannot feel that affection in its entirety! You will feel it when you become a man […]. You will feel it in more proud and vigorous measure on the day when the menace of a hostile race shall call forth a tempest of fire upon your country, and when you shall behold arms raging on every side, youths thronging in legions, fathers kissing their children and saying, “Courage!” mothers bidding adieu to their young sons and crying, “Conquer!” You will feel it like a joy divine if you have the good fortune to behold the re-entrance to your town of the regiments, weary, ragged, with thinned ranks, yet terrible, with the splendor of victory in their eyes, and their banners torn by bullets, followed by a vast convoy of brave fellows, bearing their bandaged heads and their stumps of arms loftily, amid a wild throng, which covers them with flowers, with blessings, and with kisses. Then you will comprehend the love of country; then you will feel your country, Enrico. It is a grand and sacred thing. May I one day see you return in safety from a battle fought for her, safe,—you who are my flesh and soul; but if I should learn that you have preserved your life because you were concealed from death, your father, who welcomes you with a cry of joy when you return from school, will receive you with a sob of anguish, and I shall never be able to love you again, and I shall die with that dagger in my heart.

Thy Father.

This mass education in fighting and, if need be, dying for the patria was not merely intended to steel the people for the eventuality—rather unlikely at the time of writing—of a foreign invasion by “a hostile race.” As the ominous cry of “conquer!” indicates, it looked forward, if anything, to an Italian invasion of the lands of foreign races. For these were precisely the years when Italy was starting to enter the fray of colonialist enterprise, in a way which was itself largely meant to provide a solution for domestic unrest, both by providing a proper national destination for the millions of Italian migrants who could not find employment on the peninsula, and by finally uniting Italians in a glorious, shared venture. But this liberal-imperialist hope again proved elusive, and the “wild throng” greeting the victorious troops remained largely a fantasy. In March 1896 the fantasy even became a nightmare when Italy was humiliatingly defeated by Ethiopian forces in the Battle of Adowa, resulting in demonstrations and riots in many Italian cities, forcing Crispi’s resignation. Colonialism failed to provide the glue that will bind the masses to the state since, as Finaldi (2017: 3) explains in a fine study of 19th-century Italian colonialism, the

reality of migration to the Americas kept the gaze of many among Italy’s poor away from colonial daydreams. Other places could be metaphorically migrated to as well: socialism promised a world that contradicted the self-sacrificing patriotism and obedience expected by the liberal order.

Thus, by the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century the sense of middle-class elation brought about by the successful culmination of the Risorgimento some four decades earlier, gave way to profound disillusion with a reality of a divided nation, whose masses have not only failed to live up to the bourgeoisie’s expectations, but were busily undermining the national edifice by way of their independent class politics. In many bourgeois politicians and intellectuals this produced profound resentment of the masses that seemed intractable to both Giolitti’s conciliatory carrot and Crispi’s authoritarian stick. Other, even more drastic means for nationalizing the masses began to be contemplated in nationalist bourgeois circles.

An excellent glimpse into this mindset is afforded by one of the great historical novels of the era, Luigi Pirandello’s pre-war I vecchi e i giovani of 1913 [The Old and the Young], which unfolded a vast panorama of Sicilian society and politics in the turbulent 1890s. At the story’s center was the uprising and eventual brutal suppression of the Fasci Siciliani dei Lavoratori during the early 1890s. The Fasci Siciliani was a democratic and socialist federation of peasant and workers leagues that took inspiration from earlier workers’ Fasci formed in the North of Italy in the 1870s. While led by urbane socialist intellectuals, it was infused with a millenarian outlook that foresaw the imminent coming of an egalitarian order, abolishing all injustice and poverty (Hobsbawm 1959: 93–107). Amidst profound economic crisis, the Fasci gathered behind it the island’s poor and confronted Sicily’s landowners and industrialists with a series of radical demands for land redistribution, raising the minimum age for work at the sulfur mines to 14 years of age, reducing working hours, etc. When most of these demands were rejected, the social conflict intensified and eventually reached the proportions of a popular uprising, with the élites asking for the government to send in armed forces to restore order. While prime minister Giolitti complied with this demand, his measures were still relatively mild, and it was only after his resignation in 1893 in association with a banking scandal and the much harder line imposed by his successor Crispi in 1894, including declaring a state of siege throughout the island and sending in some 40.000 troops, that the movement was finally quashed. The Fasci’s “leaders were arrested and sentenced to long terms in prison; the Socialist Party was suppressed; and the electoral registers were ‘revised,’ and more than a quarter of all Italian voters (most of them poor) were disenfranchised” (Duggan 1994: 167–168).

Pirandello’s novel, that heavily draws upon autobiographic materials and displays a broad first-hand knowledge of Sicily’s political and economic conditions—Pirandello came from a wealthy family involved in the sulfur industry—is to a certain extent polyphonic, in that the viewpoints of various classes (especially the aristocracy and the bourgeoisie, but also the working class and the peasantry) and of different political factions (die-hard adherents of the deposed House of Bourbon, right-wing liberals, left-wing liberals, conservatives, and radical socialists) is represented. But the predominant perspective is by far the allegedly impartial, merely patriotic one, of the veteran heroes of the Risorgimento, now being besieged on all sides by vilifying forces, their historic and self-sacrificing work dragged in the mud, on account of their own failings, but mostly since it is ill-understood by the ingrate, cynical and self-seeking nation. Pirandello himself embodies the aforementioned transmogrification of liberalism, shifting from a progressive to a reactionary position: coming from a family of zealous patriots that participated in the struggles of the Risorgimento, as a young man he was radical in outlook, and supported the Fasci’s bid for social justice; by the time the novel was written, however, he had long left behind him such radicalism, and was an embittered national conservative (for a detailed account of the author’s political trajectory, see Providenti 2000), espousing a pessimistic life philosophy stressing the absurdity of existence, which he derived to a significant extent from the German idealism he admired (on Pirandello’s profound affinities with Nietzsche, see Romano 2008). Later on, Pirandello would become a supporter of fascism and in 1935 he will gladly donate the literature Nobel Prize medal he won a year earlier as part of the “Gold for the Fatherland” campaign, launched by the regime to finance the war with Ethiopia in defiance of the international economic sanctions imposed on Italy (on the general compatibility between Pirandello’s worldview and fascist politics, see Venè 1971).

Élite anxieties vis-à-vis the unruliness of the poor find expression throughout the novel but are most systematically articulated during a private meeting of several old heroes of the Risorgimento, who have come to support the candidacy of an old liberal friend who has returned to Sicily from Rome, amid rumors that the Fasci’s socialist candidate, a certain Zappala, is quickly gaining ground among the discontented. “One Zappala only?” fumes one of the old liberals, and continues sardonically:

“No! Five hundred and eight Zappalas, one for every constituency in the Peninsula! [….] The first thing would be to abolish all the schools! Abolish all taxation! Abolish the army and the police! Law and order, soap and water! The frontiers levelled, and universal brotherhood!”

(Pirandello 1928)

He then recites a lampoon on humanism by the poet Giuseppe Giusti, bemoaning the way the masses reject Italy in favor of vacuous internationalism:

Differences of custom and clime are fancies of the past; we have changed the tune. Deserts, mountains, seas, are frontiers only in the almanacs, dreams of geographers…. And do you keep silence now, O Muse, who weary me with the plea of love of country. I am a child of the universe, and it seems to me a waste of time to write for Italy.

When he finishes, the patriots rise up and enthusiastically applaud. Another speaker then laments the rise of “the Fourth Estate,” whose preposterous “drunkard’s nightmare” of a welfare state benefitting all at the expense of the well-off, pampering the ever more ambitious proletariat, is abetted by the feeble resistance of a confused and sentimental ruling classes. While this picture of élite meekness seems questionable as a description of the actual bourgeoisie of the 1890s, it was certainly inadequate at the time the novel was written, for this was a period marked by what historian Alexander De Grand (1982: 13) called “new bourgeois militancy,” in which leading young critics of the Giolittian establishment, such as Enrico Corradini, Alfredo Rocco or Luigi Fedrezoni, brandished an “antidemocratic, elitist, imperialist ideology of extreme bourgeois politics.”

The novel’s tragic hero—perhaps the only figure who emerges as unambiguously worthy of admiration—is Mauro Mortara, a selfless, rugged, and aging Risorgimento foot-soldier of humble origins, who has dedicated his entire life to the cause of Italian renaissance without expecting any reward. A firm believer in the glory of the nation and its right to imperial expansion, which he eagerly anticipates, he lives isolated from the world, working as a housekeeper in the decaying estate of a dreamy, life-weary, petty-aristocrat. Mortara’s old age is sweetened by the blissful illusion of the nation’s grandeur, but he is gradually exposed to the sordid reality of contemporary Italy and the way the heroes of the past are everywhere on the defensive. And while he is furious with all social and political intrigues, undercutting the sacred cause of the patria, the worst renegades are by far the ignominious socialist Fasci, wreaking havoc in his beloved Sicily. Upon hearing of the clashes between the army and the rioters, Mortara, now over 80 years old, takes to arms to render Italy a final service by ridding her of the anti-patriotic brigands and traitors. He rushes to the aid of Crispi’s troops, which, mistaking him for a member of the mob, shoot him down, symbolizing the travesty which is modern Italy.

The novel ends on an ominous note, one of its last passages containing heavy hints of Italy’s near future and the rise of a new movement, an anti-fascist fascism, whose goal will be to subdue the revolting masses and salvage the Risorgimento. The following is written, remember, in 1913, when a certain Benito Mussolini is still an ultraist socialist leader:

Mauro […] begun to make preparations for departure. At his age? Sangue della Madonna, what had age to do with it? Who dare speak of age, to him! […] Armed to the teeth, ready for any provocation, he would go up to Girgenti, to discuss and arrange some plan of campaign with the other veterans, Marco Sala, Celauro, Trigona, Mattia Gangi, who surely, if the blood still flowed in their veins, must feel, as he did, the need to arm themselves and rally in defense of their common handiwork. If their enemies were united, banded in Fasci, why could not they unite, band themselves in a Fascio of their own, of the Old Guard? The troops were not sufficient; civilians must give them solid support, forcibly disband these Fasci, scatter all these dogs with powder and shot, if need be.

(Pirandello 1928)

Of all the experiences which made his life what it was, Baudelaire singled out being jostled by the crowd as the decisive, unmistakable experience. […] To heighten the impression of the crowd’s baseness, he envisioned the day on which even the fallen women, the outcast, would readily espouse a well-ordered life, condemn libertinism, and reject everything except money. Betrayed by these last allies of his, Baudelaire battled the crowd—with the impotent rage of someone fighting the rain or the wind.

Walter Benjamin (2003: 343)

Let us now turn to the response to the demographics of mass society, which as observed encompassed above all population growth and urbanization. To many members of the upper classes, the nobility and the bourgeoisie, these developments gave cause to a feeling of suffocation, spiritual no less than physical, intolerable congestion, dirt, pollution, moral and physical decline (or “degeneration” as it was widely referred to), loss of intimacy and of personal security, and even a threat to one’s sense of selfhood, as the individual felt that he or she were about to be swallowed up by the crowd.

Ortega’s description has numerous antecedents going many decades back. But it should be kept in mind that this fear and loathing were the result of a certain social sensibility, expressing the subjective viewpoint of the writers, who nearly always came from the ranks of the “better” classes. It was a product of an interpretation of modern society, reflected, one might say, through a distorting mirror, to use the apt formulation proposed by Susanna Barrows (1981) in her excellent study of upper-class’ responses to the masses in late 19th-century France. The same phenomena could be construed—as indeed they sometimes were—in a positive way, not with fear but with hope.

To illustrate this fact, let us examine a text, in this case a visual one, Eugène Delacroix’s celebrated La Liberté guidant le people (Figure 2.1), one of the iconic paintings of the 19th century, drawn in 1830 as an homage to the popular uprising of the same year in which commoners—workers as well as members of the middle class—rose up against King Charles X and deposed him, thus terminating the Bourbon Restoration in France.

This visual hymn to the popular revolt, has two main protagonists: “liberty,” represented by the female flag carrier holding a gun, and “the people,” that is present as the sum total of the participants. Among them, to the left of liberty, is a gentleman wearing a cylinder hat and a black jacket and holding a musket gun. Although this cannot be known without additional information, this is a self-portrait of the painter, Delacroix (Néret 2000: 25). He joins the street fighters (at least vicariously: Delacroix did not actually take part in the fighting), and in spite of his somewhat more elevated social status, indicated by his attire, sees himself as one of the crowd. A common third estate front of workers and middle-class individuals closes ranks in defiance of the enemies of the people, the nobility and the monarchy. The vision reflected in the painting is boldly popular, democratic and plebeian. Liberty herself is one of the populace; the people are “guided” by one their own, not by any élite, whose corrupt members they in fact seek to depose. The mass is positively depicted, indeed celebrated. The identity of the participants is not lost once they join the crowd, as a later trope would have it, but is enhanced. They gain individual expression precisely because they have joined a group that fights for its rights. One could assume, for example, that the urchin depicted to the right of liberty, waving two revolvers, would not have been represented in another painting, and certainly not as a distinct protagonist of the events. In fact, he got to express his individuality further in the field of literature, since Gavroche of Les Misérables was reputedly inspired by his figure. At this, relatively early historical phase, the people has not yet been transformed into a rabble. The definitive rift between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat has not yet opened: this will happen only during the next revolutionary wave, the 1848 revolutions, when for the first time full-scale fighting between the middle class and the working class shook Paris.

Ten years later, in 1840, Edgar Allan Poe wrote his short story The Man of the Crowd, which also centers on the adventures of a bourgeois among the common people in the big metropolis, in this case London. Like the character of Delacroix in Liberty, this story’s narrator and protagonist is not a member of the lower orders. Very little information concerning him is provided, yet he is sufficiently well-off to spend the day in a coffee house—“with a cigar in my mouth and a newspaper in my lap” (Poe 1982: 475)—and the night chasing figures stirring his curiosity. While a story’s narrator, of course, is not automatically or seamlessly the mouthpiece of the author, in this instance everything indicates a basic resemblance and affinity between them, in terms of social origins, sensibility and worldview, so that, like the painter’s delegate in Liberty, we have here the writer’s representative on the scene of action. This supposition is also supported by further information, not included in the story itself, to which we shall return.

Yet here the resemblance between the two figures—“Delacroix” in Liberty and the narrator of The Man of the Crowd—exhausts itself. In the former case, the artist is an integral and empathetic participant in the revolutionary collective storming Paris; in the latter, the narrator is a detached observer of the crowd, removed, reserved and even, as becomes increasingly clear as the story unfolds, hostile. As in the usual detective story, a genre pioneered by Poe, here too a mystery needs to be solved and a crime explained: the narrator, it turns out, seeks to fathom the riddle of the crowd, which is generally associated with criminality. While no concrete crime is committed, The Man of the Crowd can be read as the ultimate crime mystery, since the crowd is construed as the criminal par excellence. Already at the beginning it is stated that “the essence of all crime is undivulged,” (Poe 1982: 475) and the offender’s identity is revealed a few lines before the end (481): the man of the crowd is “the type and the genius of deep crime.” The mass is defined as “the worst heart of the world.”

While in Delacroix “the people” is a noble and admirable entity, the man of the crowd is demonic. In terms of his social origins, while it appears initially to be unclear—the masses observed are said to display “innumerable varieties of figure, dress, air, gait, visage, and expression of countenance” (476)—it becomes evident that the core of the mass, its innermost essence, are the lower and poorer social orders: we approximate the wicked and evil inside of the mass the more the day fades and the night deepens. The mystery increases the more the upper classes evacuate the scene and it is filled with the commoners. Thus, in describing the respectable passers-by, the lack of mystery is underlined (476):

There was nothing very distinctive about these two large classes beyond what I have noted. Their habiliments belonged to that order which is pointedly termed the decent. They were undoubtedly noblemen, merchants, attorneys, tradesmen, stock-jobbers […] men of leisure and men actively engaged in affairs of their own—conducting business upon their own responsibility. They did not greatly excite my attention.

Crime, clearly, need not be sought after in the “decent” classes. The bourgeois, moreover, exhibit passivity, embarrassment and impotence when dealing with the proper crowd, with whose aggression and pushiness they do not know how to cope (476):

By far the greater number of those who went by had a satisfied business-like demeanor, and seemed to be thinking only of making their way through the press. [W]hen pushed against by fellow-wayfarers they evinced no symptom of impatience, but adjusted their clothes and hurried on. Others, still a numerous class, were restless in their movements, had flushed faces, and talked and gesticulated to themselves, as if feeling in solitude on account of the very denseness of the company around. When impeded in their progress, these people suddenly ceased muttering, but re-doubled their gesticulations, and awaited, with an absent and overdone smile upon the lips, the course of the persons impeding them. If jostled, they bowed profusely to the jostlers, and appeared overwhelmed with confusion.

When the narrator finally detects genuine crooks, he explains that these pickpockets merely try, in vain, to look respectable: “I watched these gentry with much inquisitiveness, and found it difficult to imagine how they should ever be mistaken for gentlemen by gentlemen themselves” (476–477). Real horror and mystery begin only when one climbs down the social ladder: “Descending in the scale of what is termed gentility, I found darker and deeper themes for speculation” (477). The hierarchy of crime runs inversely to the hierarchy of class: “As the night deepened, so deepened to me the interest of the scene,” states the narrator, and further elaborates:

the general character of the crowd materially alter (its gentler features retiring in the gradual withdrawal of the more orderly portion of the people, and its harsher ones coming out into bolder relief, as the late hour brought forth every species of infamy from its den).

(478)

This is the context in which there suddenly leaps forward the monstrous criminal after whom the story is titled, the devilish “man of the crowd”:

I was thus occupied in scrutinizing the mob, when suddenly there came into view a countenance (that of a decrepid old man, some sixty-five or seventy years of age)—a countenance which at once arrested and absorbed my whole attention, on account of the absolute idiosyncrasy of its expression. Any thing even remotely resembling that expression I had never seen before. I well remember that my first thought, upon beholding it, was that Retzch, had he viewed it, would have greatly preferred it to his own pictural incarnations of the fiend.

(478)

This demonic quality is a class token of the cockney, re-emerging in its fullest horror towards the end of the story as the man of the crowd reaches a den of gin, that typical working-class drink, signifying that we have landed at the very opposite side of the spectrum from which we have started: the respectable coffee-house in which the narrator was sitting as the story began: finally

large bands of the most abandoned of a London populace were seen reeling to and fro. The spirits of the old man again flickered up […]. Once more he strode onward with elastic tread. Suddenly a corner was turned, a blaze of light burst upon our sight, and we stood before one of the huge suburban temples of Intemperance—one of the palaces of the fiend, Gin.

(481)

Demographically, the story takes place in the urban congested center par excellence, London, which as the American reader is instructed, is characterized by inconceivable population density (479):

It was now fully night-fall […]. [T]he press was still so thick that, at every such movement, I was obliged to follow him closely. The street was a narrow and long one, and his course lay within it for nearly an hour, during which the passengers had gradually diminished to about that number which is ordinarily seen at noon in Broadway near the Park—so vast a difference is there between a London populace and that of the most frequented American city.

The liberty hailed by Delacroix is for Poe mere anarchy, a helter-skelter of senseless pleasures, sin and crime. The modern metropolis is for the French artist a site of social struggle, embodying not just poverty and crime but also hope for a better world. Poe’s London, by contrast, is just a huge den of corruption. There is no politics in The Man of the Crowd. It is not known whether the narrator supports the extension of the franchise or not, endorses or opposes the right of workers to unionize, and so on and so forth. Yet given the disparagement of the commoners permeating the story, it would be surprising if one discovered that Poe was a zealous democrat. And indeed, he was democracy’s staunch opponent, refusing all social forms in which the people are sovereign. This stance emerges in the following story (Mellonta Tauta) where a future state of things is imagined—the date is 2048—in which democracy and republicanism are a thing of the past, leaving behind them just a memory, and a bad one at that:

A little reflection upon this discovery sufficed to render evident […] that a republican government could never be any thing but a rascally one. While the philosophers, however, were busied in blushing at their stupidity in not having foreseen these inevitable evils, […] the matter was put to an abrupt issue by a fellow of the name of Mob, who took every thing into his own hands and set up a despotism, in comparison with which those of the fabulous Zeros and Hellofagabaluses were respectable and delectable. This Mob (a foreigner, by-the-by), is said to have been the most odious of all men that ever encumbered the earth. He was a giant in stature—insolent, rapacious, filthy, had the gall of a bullock with the heart of a hyena and the brains of a peacock. He died, at length, by dint of his own energies, which exhausted him. Nevertheless, he had his uses, as every thing has, however vile, and taught mankind a lesson which to this day it is in no danger of forgetting—never to run directly contrary to the natural analogies. As for Republicanism, no analogy could be found for it upon the face of the earth—unless we except the case of the “prairie dogs,” an exception which seems to demonstrate, if anything, that democracy is a very admirable form of government—for dogs.

(Poe 1982: 390–391)

In Poe, as can be seen, criticism of the demographics of mass society went hand in glove with a refutation of its politics.

It should be noted that while the man of the crowd is described as “the type and the genius of deep crime,” the narrator, although pursuing him for a whole day and night and scrutinizing his every move, does not actually catch him red-handed committing any illegal act. His criminality is merely assumed, and the narrator fancies he has detected some incriminating signs, although he admits that they were quite intangible:

I had now a good opportunity of examining his person […] and my vision deceived me, or, through a rent in a closely-buttoned and evidently second-handed roquelaire which enveloped him, I caught a glimpse both of a diamond and of a dagger.

(479)

His “crime,” it would seem, is actually a very paltry one: that of sociability itself. “He refuses to be alone,” states the narrator in the concluding lines, as if this provided cause for legal action. Yet for Poe, the seclusion of the individual within himself and the distancing from the others, especially when they come from the lower classes, was considered of great merit, as testified by the story’s motto, taken from La Bruyère: “Ce grand malheur, de ne pouvoir être seul” [This great unhappiness, of not being able to be alone]. This conviction also found expression in one of Poe’s early poems Alone, written when he was 20 years old.

Alone

From childhood’s hour I have not been

As others were—I have not seen

As others saw—I could not bring

My passions from a common spring.

From the same source I have not taken

My sorrow; I could not awaken

My heart to joy at the same tone;

And all I lov’d, I lov’d alone.

Then—in my childhood—in the dawn

Of a most stormy life—was drawn

From ev’ry depth of good and ill

The mystery which binds me still:

From the torrent, or the fountain,

From the red cliff of the mountain

From the sun that ’round me roll’d

In its autumn tint of gold—

From the lightning in the sky

As it pass’d me flying by—

From the thunder and the storm,

And the cloud that took the form

(When the rest of heaven was blue)

Of a demon in my view.

(Poe 1982: 1026)

Already here the tendency is evident to take distance from the common—in the sense of something “general” and possibly also in the social sense of that which is “low” and “simple.” In a romantic and expressionistic vein, Poe’s writing gives precedence to his inner feelings and subjective impressions over external, objective reality. The poet projects onto the nature surrounding him—the cloud, the sky and so on and so forth—his internal sensations and bestows upon it a sense of “mystery,” a “demonic” aspect, in the same way that he would later invest a man in the crowd with fiendishness.

This reflects a distancing from realism, the literary genre that was dominant in the first half of the 19th century, and which strove to reflect objective reality as closely as possible, registering, in particular, social and historical processes. The great realistic novels of the age, by writers such as Walter Scott, Honoré de Balzac, Stendhal, or Charles Dickens, attempted to unfold the vastest possible panorama of society and of the relationship between its various groups and classes (as discussed by Frye 1990; Lukács 1964; Jameson 1981). In realistic literature a great number of characters, representing all walks of society, were given the possibility to speak, hence the characterization of the novel as a “dialogic” genre. In addition to this polyphonic nature, many of these novels were characterized by a sympathetic point of view of the commoners, members of the third estate, and their heroes and anti-heroes were often plebs. Poetry, by comparison, is mostly a form of personal expression, giving voice to the poet’s thoughts, moods and mindset, in a way that is less concerned with reflecting the views of those around him or deciphering the relationships between them. In the move from realism to romanticism, from objectivity to subjectivity, and from dialogue to monologue, it is possible to discern, however indirectly, the historical process whereby the middle-classes—from whose ranks came most artists and writers—and the working classes drifted apart. Delacroix, although he is considered a quintessential painter of the romanticist movement, which was certainly not of one cloth, was content to portray figures of the common people, among whom he counted himself. In Poe’s story, by comparison, the narrator is hermetically shielded from society: in the course of the story he exchanges not a word with the countless people he intermingles with. Following the man of the crowd and totally intrigued by him, the possibility does not occur to him to try to engage him in conversation, ask him who he is and what is the purpose of his roaming through the streets of London. His far-reaching conclusion regarding the nature of this figure is totally one-sided and subjective: he decides that this is the fiendish “man of the crowd” and weaves an entire theory about him, without ever asking his opinion or trying to make contact with him. In that respect, Poe anticipates one of the salient features of the vast literature on the masses, which, whether scholarly or literary, is written almost universally from external and condescending perspective: no matter whether we are dealing with Hippolyte Taine, Nietzsche, Gabriel Tarde, Scipio Sighele, Le Bon, Ortega, or any other would-be mass expert, the preconceptions of the writer, mostly negative and judgmental, are projected onto the crowd, without in any way engaging it or any of its perceived members. “The idea of empirical investigation”—writes Susanna Barrows (1981: 87) apropos Taine, the pioneer of mass psychology in France—“was wholly alien to Taine; when conversing with Gabriel Monod about his impending research trip to Italy, Taine asked, ‘And what theory are you going to verify there?’”

The rise in average life expectancy, the decrease in the rate of mortality and the growth of population are presumably salutary developments. One would have expected that contemporaries would enthusiastically welcome the possibility to live a healthier and longer life. Yet at least as far as mass critics were concerned, these demographic trends were construed as fundamentally negative, both quantitatively and qualitatively. With regards to quantity, a common complaint alleged that there were now too many people. And as far as quality is concerned, it was presumed that population growth is no neutral process, benefiting all in equal measure, but one that decisively favors the masses, the lower orders, the supposedly inferior segments of the population at the expense of the upper and middle classes.

The assumption underlying such complaints was that birth rate was highest among the poor, while the number of middle-class’ births remained, at most, stable, which meant that their proportion in society diminished from generation to generation. Several key processes were perceived as contributing to this social deterioration in which the “better” classes were dwindling while the lower classes were multiplying, primary among them the slowing down or outright cessation of the process of natural selection. According to the theories of social Darwinism, fashionable and prestigious in equal measures, under “normal” conditions the surplus population naturally thins out since it comprises those who are physically weak, too poor to provide for themselves, too lazy, reckless or stupid to succeed, for which they frequently pay with their lives, or at least cannot be expected to live very long. Thus, the balance is kept between the better and lesser members of society.

Yet modern developments, and here demographics and politics seemed to be feeding off each other, were undercutting this process: the medical improvements that have been described—medicines, vaccinations, hygiene and improved diet—presently permitted to artificially extend even the lives of those who should duly and naturally have passed away. Under natural circumstances, i.e., pre-modern ones, members of the nobility and the bourgeoisie, whose livelihood was guaranteed, who enjoyed good diet and led a healthy way of life, tended in any case to live long. But now, it was argued, the lives of the poor were extended, those who in the past could scarcely survive to old age. Now they receive vaccines that turn them less vulnerable to natural culling. Worse still, modern, mass politics boosted further the effects of demographics and medicine: due to the extension of the franchise the poor can now extend the range of medical services provided by the state, and therefore lengthen their life expectancy even more. This they do fundamentally by progressive taxation that comes at the cost of the affluent taxpayer from the middle and upper classes. As a result, these classes, thrifty, industrious and productive, grind under the “tax burden” and are compelled to finance the services enjoyed by the undeserving. If all this is not bad enough, argued the critics of the mass, the problem gets even worse once the long-term impact of the demographic changes on the political power relations is considered: the population growth of the lower orders becomes a superb political tool, allowing them to accumulate ever more power vis-à-vis the élites.

Democracy was seen as the displacement of quality by quantity, the triumph of “the great number.” Consequentially, the greater the number of the masses the more they can cash in on politically, empowering themselves from one election to the next, while the parties of the bourgeoisie, whose number of voters stagnates, progressively lose ground. As we saw, the advances of the workers’ parties seemed to confirm this scenario: in Germany, as will be recalled, the socialists were growing apace up to the First World War. And the more political power they enjoy, the more they can, in principle, tax the bourgeoisie, extort more and more services from the state, and thus live longer, procreate more and increase their number and then further expand politically. Seen from the vantage point of the upper and middle classes, this process looked like a dismal vicious cycle allowing no escape (Table 2.1), at least as long as democracy continues to exist.

Confronted by this abysmal cul-de-sac, at least as perceived by many among the élites, the complaint against “parasitism” became a recurrent trope in the political discourse, and would later feature prominently in fascist—especially Nazi—ideology. The mass was blamed for living parasitically, feeding off the strong and extorting from their talent and hard labor undue advantages. This condition was perceived as morally distorted—the weak, being the majority, exploit their numbers to prey on the strong, who are fewer and thus cannot defend themselves—and economically detrimental: the more the masses would burden the economic engine (i.e., the industrious bourgeoisie, pulling the rest of the train’s cars along) the more the economy will lose momentum or stop altogether. For Pareto (1966: 139), the liberal critic of mass democracy, it was a system that delivered the helpless economy into the hands of the unfit: “Tilling a field to produce corn is an arduous labor,” he wrote.

On the other hand, going along to the polling station to vote is a very easy business, and if by so doing one can procure food and shelter, then everybody—especially the unfit, the incompetent and the idle—will rush to do it.

This condition, he asserted (302–303), is unsustainable and sooner or later the economy will collapse under the weight of the bloated mass parasites:

[T]he workers prefer the tangible benefits of higher wages, progressive taxation and greater leisure […]. It may be “just, laudable, desirable, morally necessary” that the workers should labor only a few hours each day and receive enormous salaries; but […] is this in reality possible, that is, in terms of real, not merely nominal, wages? And what will be the consequence of this state of affairs?

A highly interesting example of the complaint against mass parasitism is provided by Nietzsche. His use of this trope is intriguing both on account of its habitual flagrancy, which helps clarify the issues at stake, and because it exposes the contradictions and inner tensions characterizing the discourse on the parasitism.

The notion of parasitism was of some importance in Nietzsche’s social thought. Like many middle-class individuals of his time he was greatly distressed by the demographic imbalance, perceivably favoring the masses at the expanse of the élites. He gave a lot of thought to the matter, and advocated a variety of ways of coping with this problem. First, he wanted to affect the consciousness of the weak, those who he felt did not deserve to go on living, and to encourage them to forsake their lives of their own accord with a view to the greater social good. In Twilight of the Idols (1888–89), Nietzsche demanded that invalids be given clear indications by their doctors that their presence among the living is no longer appreciated. This is the proposition of the passage whose title is “A moral code for physicians”:

The invalid is a parasite on society. In a certain state it is indecent to go on living. To vegetate on in cowardly dependence on physicians and medicaments after the meaning of life, the right to life, has been lost ought to entail the profound contempt of society. Physicians, in their turn, ought to be the communicators of this contempt—not prescriptions, but every day a fresh dose of disgust with their patients. […] To create a new responsibility, that of the physician, in all cases in which the highest interest of life, of ascending life, demands the most ruthless suppression and sequestration of degenerating life—for example in determining the right to reproduce, the right to be born, the right to live.

(Nietzsche 1990: 99)

It needs to be borne in mind that this was asserted at a time that the German state was exasperatingly moving in the opposite direction: rather than pushing the invalids to suicide, it introduced legal and material measures that encouraged them to go on living, such as health insurance (1883), accident insurance (1884) and the Invalidenversicherung (1889). Going on, Nietzsche turned from the parasite’s physician, to the parasite himself; here, his strategy was not to threaten but to convince the parasites to do the right thing, i.e., put an end to their unworthy life:

To die proudly when it is no longer possible to live proudly. Death of one’s own free choice, death at the proper time […]. We have no power to prevent ourselves being born: but we can rectify this error—for it is sometimes an error. When one does away with oneself one does the most estimable thing possible: one thereby almost deserves to live…. Society—what am I saying! life itself derives more advantage from that than from any sort of “life” spent in renunciation, green-sickness and other virtues—one has freed others from having to endure one’s sight, one has removed an objection from life.

(Nietzsche 1990: 99–100)

Nietzsche’s notion of what it means to be sick or invalid, moreover, was very broad and inclusive. It encompassed not only those deemed physically unfit, but the mentally ill as well, those suffering from a spiritual defect and even those who were simply considered mediocre, without any special abilities, and hence categorized as failures. As Zarathustra proclaimed: “The earth is full of the superfluous, life has been corrupted by the many-too-many. Let them be lured by ‘eternal life’ out of this life!” (Nietzsche 1969: 72). Or in the passage entitled Of Voluntary Death:

For many a man, life is a failure: a poison-worm eats at his heart. So let him see to it that his death is all the more a success.

Many a man never becomes sweet, he rots even in the summer. It is cowardice that keeps him fastened to his branch.

Many too many live and they hang on their branches too long. I wish a storm would come and shake all this rottenness and worm-eatenness from the tree!

I wish preachers of speedy death would come! They would be the fitting storm and shakers of the trees of life!

(Nietzsche 1969: 98)

Elsewhere (224), Zarathustra recommends a shock-therapy that will sift those who fake sickness from those who are genuinely incurable. The former should be forced to abandon their parasitic shirking of competition; the latter should be extinguished:

But you world-weary people! You should be given a stroke of the cane! Your legs should be made sprightly again with cane-strokes!

For: if you are not invalids and worn-out wretches of whom the earth is weary, you are sly sluggards or dainty, sneaking lust-cats. And if you will not again run about merrily, you shall—pass away!

One should not want to be physician to the incurable: thus Zarathustra teaches: so you shall pass away!

“The weak and ill-constituted,” Nietzsche (1990: 128) defiantly declares in The Anti-Christ, “shall perish: first principle of our philanthropy. And one shall help them to do so.” And in his last book, Ecce Homo, one finds the following prediction:

Let us look a century ahead, let us suppose that my attentat on two millennia of anti-nature and the violation of man succeeds. That party of life which takes in hand the greatest of all tasks, the higher breeding of humanity, together with the remorseless extermination of all degenerate and parasitic elements, will again make possible on earth that superfluity of life out of which the dionysian condition must again proceed.

(Nietzsche 1992: 51–52)6