3

Bee Specifics

General ways to make your garden

more bee-friendly

Although we are concentrating on plants for bees in this book, it is worth looking very briefly at some general factors that can make the garden as a whole more bee-friendly – things like providing water, and suitable habitats for bumblebees and solitary bees; and, if you wish to keep honeybees for yourself, appropriate locations for beehives.

Water for bees

Like every other living creature, bees cannot do without water; if we can provide a reliable source for them in our garden it removes the need for them to search elsewhere. You don’t need a pond – although if you do have the space for one it will attract no end of wildlife – as bees cannot land on water without breaking the meniscus (the ‘taut’ surface of the water) and they are not good swimmers! Bees will take water from any wet surface, such as grass, pebbles and even wet washing, rather than from open water.

Ideally bees like a solid surface to land and walk on to get to the water. In practice this can be achieved by placing pebbles or crocks in a watertight container and filling it up with clean water to just below the surface of the pebbles. Be sure to keep the container topped up, though; it’s surprising how much water a honeybee colony needs – up to four litres a day in some instances! I make a habit of replenishing the ‘bee water’ whenever I water my containers of plants, which, even during a rainy spell, I do at least once a day.

Bees are creatures of habit when it comes to water. Once they have found a suitable and reliable source, they are very reluctant to go elsewhere. You are likely to see other insects, birds and mammals coming to the ‘watering hole’ – I have even seen my neighbour’s elderly cat quenching her thirst at mine, although she was rather put out by being ‘dive-bombed’ by a bumblebee trying to get to the water!

Habitats for bumblebees and other bees

Even if you don’t keep honeybees yourself, or there isn’t a colony nearby, you are bound to find bees of some description in your garden. The obvious ones are the ‘fluffy’ bumblebees, but you will no doubt find solitary bees and other insects such as hoverflies. All of these have a role to play in the ecological balance of your garden, so they should be encouraged to visit and even make their home there. For advice on providing homes for bumblebees, contact the Bumblebee Conservation Trust (address at the end of this e-book).

Although you can buy ‘nest boxes’ for bumblebees and other bees, research has shown that these are frequently overlooked in favour of a site that the bees have found for themselves – so don’t be disappointed if your bijou bee residence remains empty! Some solitary bees nest in hollow stems, like bamboo canes or larger herbaceous plant stems. Others nest in the ground in bare soil or short turf, so if you see little mounds of soil appearing, don’t immediately think you have mice – it could be the beginnings of a solitary bee nest.

Siting a honeybee hive

You may like to keep honeybees yourself. It is beyond the scope of this book to look at how exactly to do this (see Further Reading for books on beekeeping), but here are a few guidelines that will help you to find the best place to put your hive, or hives, in your garden – which, hopefully, already has a good source of food in the form of bee-friendly flowers.

| • | Try to find somewhere tucked away – don’t place your hive in a position where you, your family or friends will be walking close to it on a regular basis. |

| • | Place your hive in the sun (but dappled shade will do at a push), preferably facing south. |

| • | Find a position that is sheltered from the wind. |

| • | Avoid frost hollows. |

| • | Make sure the site is not prone to flooding. |

| • | Don’t place your hive under a tree – drooping branches knocking against the hive, and water droplets falling on it during and after rain, will annoy the bees. |

| • | Make sure that you keep the area around the hive free of weeds and grass, which may hinder the bees when they leave and return to the hive. Cut back the grass and weeds – on no account use a weedkiller! |

| • | If you live in an urban area, or where you think your neighbours might be worried by the bees, place your hive in an enclosed space, partially surrounded by a fence or wall. This will encourage the bees to fly well above head height until they reach the vicinity of the hive. |

This list might seem a little long, but most of it is common sense when you look at it from a bee’s point of view.

What makes a plant bee-friendly?

When it comes to designing a planting scheme for bees, some aspects of the design considerations that we looked at earlier are more important than others. Three stand out, over and above the others, and they are the form of the flower, the colour of the flower, and what time of year the plant blooms. We need, therefore, to give these particular thought when we start putting ideas together for different borders.

I have gone into detail elsewhere about what sort of plants are best for bees and what flowers produce in the way of foodstuff for bees (see The Bee Garden – details in Further Reading), but it is worth including here some characteristics of the most suitable plants, especially for honeybees, so that we can be prepared when we come to choose plants for our borders.

I have devised the following short mnemonic to use as a sort of checklist to keep in mind when deciding what sort of plants are best for our buzzy friends:

Friends Are Very Special

You may be wondering what this has to do with plants – although I have to say some of my plants do feel like very special friends – but I will briefly explain, and then look at in a little more detail, each of the components:

Food

Why do bees visit flowers in the first place? Flowers provide food for bees in the shape of pollen and nectar; these two items, along with water, are the only foodstuffs bees need to survive. In a nutshell, it is the pollen, which is produced by the male sex organs of the plant, that supplies bees with the protein that they need for the proper growth and repair of their bodies. Nectar, on the other hand, provides bees with carbohydrate in the form of a sugary liquid which is secreted by plant nectaries.

Nectaries can be either ‘floral’, which means that they are found within the flower, or ‘extra-floral’ – located outside the flower, usually but not always at the point where a leaf joins the stem. For pollen-bearing plants, floral nectaries are of the greatest importance because the nectar attracts pollinating insects to the flower. Floral nectaries are usually found in the heart of the flower, which means that the insect has to brush past the pollenbearing stamens to get to the nectar. In effect, the nectar is the insect’s reward for being ‘hijacked’ by the flower to distribute its pollen.

Therefore, the more plants we choose that offer a good supply of pollen and/or nectar, the greater the number of bees that will be attracted to our garden.

Accessibility

There are thousands of different flowers providing varying amounts of pollen and/or nectar; a cursory glance around a well-stocked garden in the summer, buzzing with insects, is testament to that. Certain types of flowers, however, seem to attract bees more than others. This is because not only do the bees know that there is food waiting for them; more importantly, they know that they can access it.

Whether or not bees can access pollen or nectar depends on the form of the flower.

Single flowers are best

There is one particular, and very important, aspect of flower form that we need to be aware of when we are deciding which plants are best for bees: it is invariably single flowers that our buzzy friends make a bee-line for. It is rare for double flowers to provide much, if anything, in the way of bee food; the extra petals of a double flower are really a genetic mutation of the sexual structures of the flower, which means that there are no, or very few, pollen-bearing male stamens and often no nectaries. If a bee did visit, its journey would be all but wasted.

The shape of the flower

If the flower is open or cup-shaped it is very straightforward for bees to get to both pollen and nectar. If the flower is tube-shaped, however, where the petals have fused to form a corolla tube, the nectar may not be so easy to reach. Indeed, the corolla tubes of some flowers are so deep that some bees cannot access the nectar at all; only bumblebees (and sometimes only butterflies) are able to reach it. This is because of the difference in the length of the proboscis (the long, slender ‘tongue’ of nectar-supping insects, which acts as a straw).

As a general rule, if a flower is suitable for honeybees then it is highly likely to be acceptable to the vast number of other nectar-sipping and pollinating insects. I saw an example of this when I visited a garden in the north of England in late September. A swathe of Agastache ‘Black Adder’ had been planted which was proving irresistible not only to honeybees but to Red Admiral butterflies ( Vanessa atalanta) and the white-tailed bumblebee (Bombus lucorum) – all delighted in the abundant nectar (see Figures 3 and 4).

| Figure 3 Agastache and Red Admiral butterflies |

Figure 4 Agastache and the white-tailed bumblebee |

| -------------------------------- | -------------------------------- |

We look in more detail below at what families of plants are best for bees, but as a general guideline, plants with daisy or ‘pincushion’ flowers – like Echinacea sp and Knautia sp, respectively – where there are numerous small flowers collected together on one head, are really good for bees. Those with lots of individual flowers held on spikes (like Lavandula sp) are also attractive, as are larger, open flowers, like single species of Rosa (rose) and Fragaria sp (strawberry).

Native flowers

What has become clear to me, as a beekeeper as well as a gardener, is that the nearer a plant is in form to its ‘wild’, original species, the more attractive it is to bees. This is because the original species have evolved naturally, without human interference, to attract the pollinating insect that is best suited to their needs. Some plants have evolved to such a degree that they can only be pollinated by one particular agent. For example, the Chinese orchid, Cymbidium serratum, is only pollinated by a wild mountain mouse, Rattus fulvescens – yes, a mouse! I don’t think any of our native species have evolved quite that far, but it is true to say that the flower of each native species has developed to draw the attention of a suitable pollinator.

This doesn’t mean, of course, that we should only plant native species in our gardens. Many cultivated varieties are not only attractive to us but they are also good for bees. So, hopefully, we can have the best of both worlds.

Visibility

We looked at colour from a design perspective in Chapter 2, but we need to consider the extra dimension of bees’ vision in order to see how this might affect how we go about choosing plants for our bee-friendly borders.

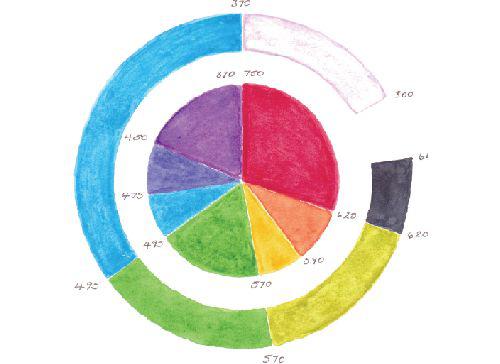

Bees ‘see’ differently from humans. We can see all the colours of the rainbow, from red through to violet (750–370 nanometres (nm)); bees see less than us at one end of the colour spectrum but more than us at the other end (650–300 nm). Bees do not see red (620–750nm) as we do, and we cannot see ultraviolet (300–370nm).

Bees’ vision is complex, and although they can detect a fairly broad range of colours, what they see is less differentiated than what we see. This has a direct influence on which flowers bees are attracted to: they will automatically target flowers that stand out to them.

The illustration in Figure 5 is a slightly different sort of colour wheel: in the centre are the colours that we can see, and this is compared with how bees might see these colours, around the outside.

This is not to say that we should dismiss any colour out of hand, though: just because a flower might appear to us to be outside the bees’ visual spectrum, it doesn’t mean that it might not be appealing to them. Although we may think, from the colour of the petals, that the flowers are ‘invisible’ to bees, it is often the case that the centre of the flower, where the ‘business area’ is located, is of a colour that is well within the bees’ field of vision, especially if we take into account the part of the spectrum that we humans can’t see – ultraviolet.

Figure 5 Visual spectrum colour wheel

Flowers often have marks on their petals of a contrasting colour to the rest of the flower, or they contain UV ‘pigments’, which guide the bee to where the nectar can be found, in much the same way as airstrips have landing lights for planes. These markings are known as nectar guides.

The idea that the best form of a flower for bees is one that is closest to its native species also seems to apply to colour. Many cultivated varieties of flowers have been bred to be attractive to the human eye, but the colours of wild flowers seem to be consistent with the colours that their respective pollinators can best see.

Bees are able to detect movements at a much faster rate than humans. Bees’ eyes are compound eyes, made up of thousands of tiny lenses; these collect images that are then combined by the brain into one large picture. They can also easily distinguish between solid and broken patterns, with a preference for the latter. A mass of perennials waving slightly in a gentle breeze will be an easy target for the honeybee, and when they do start to forage, they don’t have to move very far from one pollen and nectar source to another. It is therefore best to position perennials and annuals in groups or blocks rather than as single specimens. There is not the same necessity to do this with trees and shrubs, however, because they carry many flowers on one plant.

Seasonality

Honeybees start to appear in March or April, depending on the temperature and general weather conditions. If you see a bee buzzing about the garden in late winter or very early spring and the temperature is below 6°C, then it will probably be a bumblebee of some description because honeybees will not venture outside the hive unless the temperature is above this level. Honeybees will continue flying until the first frosts, which can occur any time between late September and early December. Usually, however, once the abundant nectar that is produced by ivy flowers late in the season has been gathered, there will be very few bees around until next spring.

It is important to aim to provide food for bees and other insects for as long a period as possible when they are active. Much of the time this depends on the weather, of course. A hot, dry spring will bring an abundance of pollen and nectar, which enables honeybees to build up their colonies, but if this is followed by a cold, wet summer, with a resulting dearth of food, the colony will suffer and they may not be able to accumulate enough stores to last them through the winter. Vigilant beekeepers will be aware of this, and will provide them with specially formulated bee food to make sure that they have enough. Gardeners can’t do an awful lot to mitigate the weather induced lack of flowers, however – we can’t control the climate!

The ‘June gap’

Even in a ‘normal’ year, when we end up with the sort of weather we might expect, there are periods throughout the growing season when the border can look a little sparse. I am thinking particularly of what beekeepers call the ‘June gap’, when the abundance of spring flowers is exhausted but the early summer flush of blooms is yet to appear. (This ‘in-between’ period may not necessarily occur in June, of course; it is entirely dependent on the weather.) The ‘changeover’ between summer and autumn, too, can see the border looking a little thin.

We gardeners, however, can have a trick up our sleeve which might go a modest way towards alleviating the problem. Unlike a magician’s ruse, where one minute you don’t see it and the next minute you do, we have to think ahead a little – in fact, several weeks ahead – and sow a succession of annual seeds. By doing this we can provide a limited, but possibly crucial, supply of short-term bee-friendly plants to fill in the gaps in the border. Of course, if the weather is truly against us, even this ploy won’t work, but for the sake of a few pounds (or, even better, having saved some seed from last year’s pollinated flowers), it may provide just the snack the bees need until the next proper course appears.

Bees’ favourite plant families

By now I hope you are feeling a little more confident about choosing plants for your bee border, and about putting them together in a pleasing way. Nevertheless, there is one more suggestion that might be worth bearing in mind when it comes to choosing specific plants.

Having looked at a whole range of bee-friendly plants, it seems that a good number of them fall into two main families – enough to call them ‘Primary’ families (Asteraceae and Lamiaceae). There are four other families that have a good variety of bee-friendly plants in their ranks, and I have categorized these as ‘Secondary’ families (Boraginaceae, Ranunculaceae, Rosaceae and Scrophulariaceae). Many other plant families also contain beefriendly plants, but there are fewer instances in each of them, so in addition to the Primary and Secondary families, there is another group, in which I have lumped together lots of other families, which I have called ‘Other’.

From a design perspective, if you make sure that some of your focus plants, framework plants, flowers and fillers in your planting plan come from both of the Primary families, along with a few from the Secondary families, you will already have an interesting combination of texture and form, and you will be sure to have a bee-friendly mixture. If you have a larger area to fill, you can intersperse the Primaries with many more from the Secondary families and also include some ‘Other’ plants if you wish.

In each of the groupings below the families are arranged in alphabetical order. You will find a list of plant species arranged according to their family, for easy reference, in Appendix 1.

Primary families

If I had to choose the top bee-friendly plant families for ornamental – rather than commercial or edible – value, they would be Asteraceae and Lamiaceae. These two families contain a huge range of plants that are of utmost value to bees.

Asteraceae

The Asteraceae family used to be called Compositae, which gives a clue to the type of flowers it produces. The flower heads are a composite of lots of individual flowers; these can either be regular, with all the petals the same size, often forming corolla tubes (like the cornflower, Centaurea cyanus), or they can be irregular, with some petals bigger than others (like sunflowers, Helianthus annuus). Many members of the Asteraceae family produce prodigious amounts of pollen, and there is also a very useful ‘landing platform’ for the bees to touch down on!

Lamiaceae

Typical flowers of the Lamiaceae family have petals that have fused together into an upper and lower lip (which gave rise to the family’s former name of Labiatae), and are positioned in clusters around the stem. This means that the bee can visit scores of individual flowers on one stem to collect nectar, using very little energy and pollinating numerous flowers at the same time. The plants are often aromatic; many herbs, such as lavender ( Lavandula sp), rosemary ( Rosmarinus sp), mint ( Mentha sp), marjoram ( Origanum vulgare) and sage ( Salvia sp) belong to this family.

Secondary families

Although not containing as many bee-friendly plants as the Primary families, Secondary families include a vast number of plants that are popular with both gardeners and bees.

Boraginaceae

This family contains over 2,000 species, some of which are very useful bee plants – one of which, not surprisingly, is Borago officinalis (borage). Others include Anchusa officinalis (common bugloss or alkanet), Symphytum (comfrey), Myosotis (forget-me-not), Heliotropium (heliotrope), Pulmonaria sp and Echium vulgare (viper’s bugloss). The majority have blue or purple flowers, and hairy stems and leaves. A number of them are herbs and some are used for dye, or medicinally.

Ranunculaceae

The Ranunculaceae family contains a wide range of wild and garden flowers such as buttercups, celandine, Anemone, Clematis, and Aconitum. The flowers may be solitary, like buttercups, or they may be held on spikes, like Aconitum, or in clusters. Many species in this family have no proper petals – it is the brightly coloured calyces that we mistakenly call the flower.

Rosaceae

The Rosaceae family contains not only the rose (Rosa sp), but also many fruit-bearing plants that are worth growing in the ornamental border: species such as apples (Malus sp), cherries (Prunus sp), pears (Pyrus sp), and strawberries (Fragaria sp) all belong to this family. Other ornamental species include Cotoneaster, Geum, rowan (Sorbus aucuparia) and whitebeam (Sorbus aria). Nearly all the flowers of the Rosaceae family are regular, with five petals that form a cup-like structure, which makes it very easy for bees to reach both pollen and nectar; the flowers are nearly always carried as clusters (think of apple blossom), which means that bees can visit lots of flowers within a short distance of one another.

Scrophulariaceae

Bee-friendly plants in the Scrophulariaceae family include Digitalis, Verbascum, Penstemon, Veronica and Hebe. Nearly all the members of this family have flowers that are arranged on spikes, which means that the bee can visit a number of flowers without having to fly too far. This family contains a vast number of garden-worthy plants, too.

Other families

Many individual species that don’t belong to any of the Primary or Secondary families are, nonetheless, particularly useful to bees. These are listed in Appendices 1 and 2. Although the families to which each of them belongs may contain more bee-friendly plants than I have selected, the ones that I have chosen are, to my mind, most suitable to be included in an ornamental planting scheme.