CHAPTER THIRTEEN

DE CERIMONIIS AND THE GREAT PALACE*

J. M. Featherstone

One of the most important sources for Byzantine studies is the text commonly known as the De cerimoniis. This compilation, associated with the name of Constantine VII, is a great mine of information not only for philologists, but also for political, cultural and art historians, as well as archaeologists. The keenly antiquarian Constantine initiated this collection in the context of a renewal of court ceremonial on his accession to self-rule in 945. Here old descriptions of ceremonies were gathered together and new ones added. A subsequent redaction, with various additions, was produced some twenty years later, during the reign of the emperor Nikephoros Phokas (963–9). The text of this later version has come down to us in two contemporary manuscripts, one almost intact, now in Leipzig, and another which is preserved in two palimpsest fragments, in Istanbul and on Mt Athos.1

Regarding the purpose of his compilation, Constantine speaks of the need to restore order to imperial ceremonies, long fallen into confusion. Thereby is the power of the ruler once again to be revealed in its harmony to the subjects of the empire. Political interest clearly stood in the foreground: the significance of the emperor must be represented in magisterial wise; and the imperial court as well as the population of the empire must follow the proper order so that they might thus both honour the emperor and display the glory of the empire to other nations.2

In some parts of the De cerimoniis we find this idealized form where stress is placed on the strict order of ceremonies; but in others, reports of particular occasions have been inserted which show us imperial court ceremonial in practice. The reception of Arab envoys from Tarsus in the year 946 is a good example. As we shall see below, various ceremonies and feasts were here jumbled together: from each were taken the most striking costumes, artworks and formations, making use also of the most impressive buildings of the palace – all this with blithe disregard for the original order or significance of the various elements.

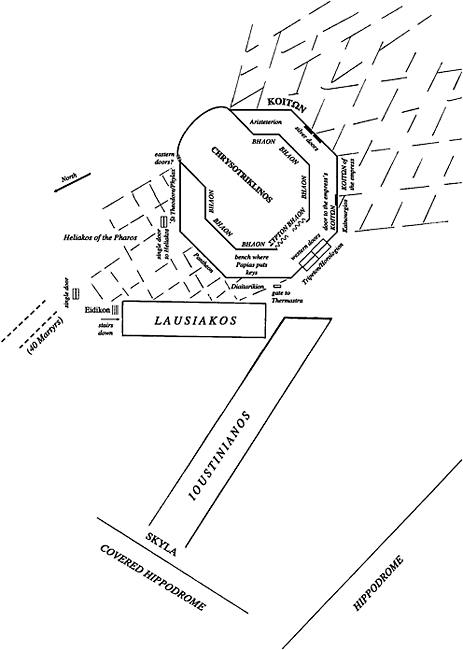

However this may be, speaking symbolically in his preface Constantine proclaims that his collected descriptions of imperial ceremonies will shine to the splendour of the imperial office like a bright mirror set forth in the midst of the palace.3 Constantine’s image rightly places the ceremonies he describes in the context of the Great Palace of Constantinople in which they had evolved over the centuries. But for us there are two problems here. First, though we can more or less trace the confines of this palace on the map of modern Istanbul, all of its many structures and spatial elements have long vanished and can only be hypothetically reconstructed on the basis of written sources, of which the De cerimoniis is the most important.4 And this brings us to the second problem: that the De cerimoniis is, to use the term applied by Cyril Mango to Byzantine texts in general, a distorting mirror.5 To begin, let us ask what Constantine VII means exactly by the word “palace,” in Greek  . The De cerimoniis contains various texts dating from the sixth to the tenth century and reflecting the Great Palace in the respective periods of its history. In the sixth-century chapters excerpted from Peter the Patrician we get a glimpse of the old Constantinian palace on the upper terrace beside the hippodrome with which court ceremonial was still very closely bound at the period.6 But in another text, the Kletorologion or Banquet Book of Philotheos, dated to 899,7 we observe that the old buildings on the upper terrace were now only used on special occasions. The everyday life of the emperors and court had shifted to the newer buildings on the lower terrace beside the Sea of Marmara, with the emperor’s Koiton or private apartments and the adjacent Chrysotriklinos as its nucleus.8 Indeed, in Philotheos and in all the chapters of the De cerimoniis dating from later periods, the term “palace,” sometimes with the epithets “God-guarded” or “sacred” – because the emperor’s person was considered sacred – is restricted to the complex around the Chrysotriklinos (Figure 13.1).9 Whereas in Peter the Patrician

. The De cerimoniis contains various texts dating from the sixth to the tenth century and reflecting the Great Palace in the respective periods of its history. In the sixth-century chapters excerpted from Peter the Patrician we get a glimpse of the old Constantinian palace on the upper terrace beside the hippodrome with which court ceremonial was still very closely bound at the period.6 But in another text, the Kletorologion or Banquet Book of Philotheos, dated to 899,7 we observe that the old buildings on the upper terrace were now only used on special occasions. The everyday life of the emperors and court had shifted to the newer buildings on the lower terrace beside the Sea of Marmara, with the emperor’s Koiton or private apartments and the adjacent Chrysotriklinos as its nucleus.8 Indeed, in Philotheos and in all the chapters of the De cerimoniis dating from later periods, the term “palace,” sometimes with the epithets “God-guarded” or “sacred” – because the emperor’s person was considered sacred – is restricted to the complex around the Chrysotriklinos (Figure 13.1).9 Whereas in Peter the Patrician  comprises all the buildings on the upper terrace,10 in the tenth-century texts the emperor is always said to leave the palace when he goes from the lower terrace to one or another of the older buildings on the upper terrace for some special ceremony or when he passes through them in procession to St Sophia on feast-days. Similarly, imperial officials on their way to daily functions are able to traverse the upper terrace freely, but they must await the opening of the precinct of the palace on the lower terrace at precise times.

comprises all the buildings on the upper terrace,10 in the tenth-century texts the emperor is always said to leave the palace when he goes from the lower terrace to one or another of the older buildings on the upper terrace for some special ceremony or when he passes through them in procession to St Sophia on feast-days. Similarly, imperial officials on their way to daily functions are able to traverse the upper terrace freely, but they must await the opening of the precinct of the palace on the lower terrace at precise times.

Thus, such famous buildings of the old palace as the Chalke Gate, the Consistorium, the Great Triklinos of the Nineteen Couches, the Augusteus and even the Kathisma, or imperial loge, overlooking the hippodrome, were no longer considered parts of the imperial residence.11 Like the adjacent Magnaura, the former Senate house on the Augustaion which was still used for grand occasions of state, the ancient structures on the upper terrace – now some 600 years old – were maintained, in a dubious state of preservation, as a sort of museum. Of course, though less carefully guarded than the actual palace, the whole area of these old buildings remained inaccessible to the general populace of Constantinople at least until the Fourth Crusade.12 But just how difficult it had become by the tenth century to maintain and defend this white elephant, and how unnecessary it was to everyday court life, is shown by the construction under the emperor Nikephoros Phokas in 969 – only a few years after the compilation of the De cerimoniis – of walls running from the hippodrome to the Sea of Marmara which cut off the palace on the lower terrace from the older buildings on the upper terrace and destroyed not a few of them.13 It was under this same Nikephoros that the Byzantines reconquered Antioch after 300 years, and if the imperial administration had deemed the old palace indispensable, there would surely have been the resources to maintain it for at least another century.

Nevertheless, the earlier maintenance and ceremonial use – however occasional – of the structures of the old palace is of great significance. They were preserved for

Figure 13.1 The Great Palace, redrawn by J. M. Featherstone from Müller-Wiener 1977.

many centuries in order, as it were, to impart the glory of the past to the image of the reigning emperor and the state. This antiquarian tendency is reflected in the composition of the De cerimoniis. Filled with descriptions of ceremonies performed in the old buildings, it tells us frustratingly little about current ritual in the actual palace or the newer buildings on the lower terrace. Such famous structures as the Sigma-Triconchus exedra where, as we know from other sources, the emperor Theophilos (829–42) preferred to spend as much time as possible, or the Nea church built by Constantine VII’s own grandfather Basil I (867–86), are described only in passing.14 But we must not let this antiquarianism obscure our view of the real state of things. By the tenth century the very names of the buildings of the old palace had gone out of common use. In a passage added to the De cerimoniis by a later redactor in the 960s concerning a reception for Arab envoys from Tarsus in 946, the Consistorium, the famed aula regia of the Constantinian palace, is repeatedly referred to as the “hall where the canopy stands and the magistroi are promoted,” as if that was all that was known about it.15 Moreover, we note here that the Consistorium and all the other buildings of the old palace through which the foreign guests were paraded were hung with silken cloths and curtains from the Chrysotriklinos and chandeliers from the Nea church. The fact is that the old buildings no longer had their own decorations or lighting, and we ask ourselves whether the many silken and embroidered cloths hung everywhere, some of them blocking off entire ways of passage, were not intended to hide the state of disrepair of these structures.16

We shall return to the buildings of the old palace later, but let us now look at what the De cerimoniis tells us about the everyday ritual in the palace proper in the tenth century. Central to this ritual was the Chrysotriklinos. Built or at least reconstructed by the emperor Justin II (565–78) at the end of the sixth century, this octagonal hall was the interface between the private apartments of the emperor, the Koiton, and the public parts of the palace. In De cerimoniis we see the Chrysotriklinos as a throne room, not for grand audiences of state as in the Magnaura with its phantasmagoric throne of Solomon,17 but for other functions such as the promotion of imperial officials, banquets and, especially, the so-called “everyday procession” when officials assembled in the adjoining halls of the Lausiakos and Ioustinianos to await possible summons by the emperor. The Chrysotriklinos is often compared with octagonal halls which have been found in positions of articulation between private apartments in other late antique palaces: in Constantinople beside the old Koiton on the courtyard of the Daphne on the upper terrace, in the Lateran in Rome (later converted into the “Baptistery of Constantine”), at Gamzigrad and elsewhere.18 Rather than look for some ideological significance, I would suggest, quite simply, that an octagonal space lent itself very well to a system of side chambers and curtains whereby the coming and going of the sovereign from his private apartments and his appearance to his subjects could be invested with the appropriate solemnity.

From the descriptions in the De cerimoniis it is clear that the Chrysotriklinos consisted of eight vaulted elements  opening onto a central space. The element on the eastern side is more precisely called a

opening onto a central space. The element on the eastern side is more precisely called a  or apse, whereas the other seven sides are always referred to as

or apse, whereas the other seven sides are always referred to as  or

or  that is, curtains, by which they were shut off from the central space. There were sixteen window vaults in a central dome, and also small windows glazed with alabaster set high up in the side vaults, whose light would have passed into the central space through openings, presumably arches, above the curtains which shut off the side vaults at floor level.19 Unlike the churches of SS Sergius and Bacchus, St Vitale in Ravenna and the Palatine Chapel in Aix, which present a similar configuration of interconnecting side galleries, the Chrysotriklinos was not a free-standing building. There were no proper windows in its side galleries but only doors opening into adjacent structures. As illustrations we reproduce the reconstruction by Ebersolt (Figure 13.2) and offer a sketch plan of the Chrysotriklinos and the surrounding buildings (Figure 13.3).

that is, curtains, by which they were shut off from the central space. There were sixteen window vaults in a central dome, and also small windows glazed with alabaster set high up in the side vaults, whose light would have passed into the central space through openings, presumably arches, above the curtains which shut off the side vaults at floor level.19 Unlike the churches of SS Sergius and Bacchus, St Vitale in Ravenna and the Palatine Chapel in Aix, which present a similar configuration of interconnecting side galleries, the Chrysotriklinos was not a free-standing building. There were no proper windows in its side galleries but only doors opening into adjacent structures. As illustrations we reproduce the reconstruction by Ebersolt (Figure 13.2) and offer a sketch plan of the Chrysotriklinos and the surrounding buildings (Figure 13.3).

The orientation of the apse to the East is not the only element of the Chrysotriklinos suggestive of an ecclesiastical structure. This apse contained an image of Christ – probably a mosaic – under which, as we shall see, the emperor or co-emperors sat to

Figure 13.2 The Chrysotriklinos, after Ebersolt 1910, folding plain.

receive the veneration of subjects and guests.20 The main entrance was on the western side, with an outside porch called the Tripeton, in which there was a clock, or sundial. The Tripeton gave on to a terrace on which were also the entrances to the halls of the Lausiakos and Ioustinianos.

As we have said, all the side vaults except the eastern apse were shut off from the central space of the Chrysotriklinos by curtains. The curtains on the western side could be drawn back in the middle, and it was through them that one was admitted into the Chrysotriklinos for an audience with the emperor sitting opposite in the eastern apse. On other occasions when the emperor was not sitting on the throne, imperial officials and guests could walk straight through the Chrysotriklinos, going in the western doors and out other doors on the eastern side, evidently in the eastern apse, which gave on to a terrace. These doors, like those of the western entrance, were of silver.21

The vault immediately to the left of the apse gave on to the chapel of St Theodore, which connected with the Phylax, or Treasury, of the palace. Like the Octagon beside the old private apartments in the upper palace, the vault in front of St Theodore’s served as a vestry. The emperor’s vestments were kept there, and he was vested behind the curtain before various ceremonies in the Chrysotriklinos or any of the churches on the lower terrace.

Proceeding counter-clockwise, the central vault on the northern side gave on to a structure called the Pantheon, about which all we know is that it was big enough for at least one high official to wait in before ceremonies; and the next vault, immediately to the left of the western entrance, articulated with the Diaitarikion or steward’s room. Behind the curtain of this vault was a bench on which the Papias, or door-keeper of the palace, placed the keys when he had opened the Chrysotriklinos. In addition to the main doors of the western entrance and those in the eastern apse, there were at least two other ways into the Chrysotriklinos on the northern side, through the Diaitarikion and the Phylax, whereby officials could come and go

Figure 13.3 Sketch plan of the Chrysotriklinos, drawn by J. M. Featherstone.

unseen behind the curtains which shut off the central space. Thus, it was this northern side which articulated with the public parts of the palace.

The vaults on the opposite, southern, side of the Chrysotriklinos gave on to the private apartments of the emperor and empress. The entrance to the Koiton of the emperor appears to have been in the wall of the central vault. There was a bench behind the curtain here, and the doors to the Koiton were of silver. The vault immediately to the right of the western entrance is mentioned as the place where the patriarch divested himself of his stole after blessing the meal at banquets; and in the wall of this same vault there was a direct entrance to the Koiton of the empress. The remaining vault, just to the right of the eastern apse, is the probable location of Constantine VII’s Aristeterion, or breakfast room, where other members of the imperial family, including the children, could come from the Koiton to join the emperor for dessert in the company of select guests at the end of banquets in the Chrysotriklinos.22

From the two comparatively scanty chapters of the De cerimoniis on everyday ritual we learn that the palace was normally opened every morning after Matins, thus shortly after dawn.23 The Hetairiarch or chief of the company of guards, together with the weekly rota quartered within the palace, first opened a complicated passage from the courtyard of the Daphne leading to the Lausiakos, and then, together with the Papias, opened the western doors of the Chrysotriklinos. Then they went into the other adjoining hall, the Ioustinianos, and passing through it, opened the gate on its opposite end which gave on, through a porch called the Skyla, to the so-called Covered Hippodrome. This latter was a part of the old upper palace, and the gate in the Skyla was the most direct entrance to the newer lower palace. Corresponding in position with the so-called Stadium of Domitian’s palace on the Palatine, the Covered Hippodrome was not a racecourse at all, but a rectangular garden surrounded by galleries. It was here that imperial officials awaited the opening of the palace and entered to take their places “in procession,” that is, in the order of their rank, on benches in the Ioustinianos.24 This daily procession is the survival of the Roman salutatio Augusti or, more particularly, the cottidiana officia, when the emperor greeted high officials. As in the case of its classical antecedent, however, we cannot know whether all imperial officials came for this procession every day: no particular officials are mentioned for weekdays. The attendance of even the highest officials is indicated on ordinary Sundays, but the procession was held on such Sundays only when the emperor so desired.25 Unfortunately, the De cerimoniis tells us nearly nothing about where the everyday business of administration was conducted. There is mention of the daily opening of bureaux  beside the Lausiakos and the Eidikon or Imperial Privy Purse, and it is here that the Logothete, or chief official for foreign affairs, awaits his summons by the emperor. We must assume that a fair number of people were admitted to these bureaux each day.26

beside the Lausiakos and the Eidikon or Imperial Privy Purse, and it is here that the Logothete, or chief official for foreign affairs, awaits his summons by the emperor. We must assume that a fair number of people were admitted to these bureaux each day.26

The procedure for the everyday procession was the following. At the end of the first hour, thus at about seven o’clock, when all had taken their places, the head of the weekly rota of servants assigned to the Chrysotriklinos knocked thrice on the doors of the Koiton. This was as close as anyone but the servants of the bedchamber got to the emperor’s private apartments.27 At the emperor’s command, the servants of the bedchamber opened the doors and vested the emperor in the skaramangion, or coloured silk tunic, which the chief of the guards had placed on the bench beside the doors to the Koiton. The emperor then entered the Chrysotriklinos and, going into the eastern apse, he did reverence to the image of Christ and sat down, not on the main throne in the centre of the apse – this was left empty on ordinary days – but on a golden sellion or chair on the left side of it.28 He then summoned the Logothete, who entered through the western curtains drawn aside by the Papias. On entering the first time – though not subsequently – the Logothete, as with everyone who entered the presence of the emperor, fell to the floor in proskynesis, or obeisance; the salutatio had given way to the adoratio already in the late antique period.29 The emperor then commanded the Logothete to bring in whomever he desired to see. On non-feast-days, when there was no special business, the Papias gave the minsai, or dismissal – from the late Latin missa – by shaking his keys at the end of the third hour, around nine o’clock. On hearing this, the officials made their way out of the Ioustinianos to go home. From notes appended to this section we learn that on ordinary Sundays the emperor sat on a sellion covered in purple silk on the right side of the throne. On weekdays he wore only a skaramangion without the gold-bordered cloak; on Sundays he also put on the gold-bordered cloak. On weekdays the high officials wore the scaramangion in the procession; on Sundays a red sagion, or short cloak. To receive foreign dignitaries, the emperor sat on the purple-covered sellion as on Sundays, wearing a gold-bordered cloak with pearls and, if he desired, a crown. A further note states that the same order was followed when the palace was opened in the afternoon, though no exact times are given.30 On Sundays, before the minsai were given, the Artoklines or banquet-master read out the names of those invited to dine. Banquets were held in the Ioustinianos or in the Chrysotriklinos itself. The emperor sat at a table set apart from the others, the  . With him sat only his family and the very highest officials such as the Caesar and zoste patrikia, the female “Girdled Patrician,” who were most often also his relations, and the patriarch. Other officials were seated at other tables in proximity to the emperor according to their rank.31

. With him sat only his family and the very highest officials such as the Caesar and zoste patrikia, the female “Girdled Patrician,” who were most often also his relations, and the patriarch. Other officials were seated at other tables in proximity to the emperor according to their rank.31

This was the bare minimum of everyday ritual. On most days it would have been augmented by other ceremonies which, depending on their solemnity, were either performed completely in the lower palace or involved going to the old upper palace and St Sophia as well. Lesser religious feasts were celebrated on the lower terrace, with a liturgy in one of the palace churches, such as the Theotokos of the Pharos on the terrace beside the Chrysotriklinos, or St Basil’s chapel in the Lausiakos, followed by a banquet.32 Such personal celebrations as the emperor’s birthday or the newly revived Broumalia were also confined to the lower terrace, with a ballet in the Sigma-Triconchus complex and a banquet in the Chrysotriklinos.33 Promotions of all but the highest officials were performed in the Chrysotriklinos, for example those of a strategos, or a koubikoularios,34 or, at a higher level, a patrikios or a zoste patrikia. Like state receptions in the Magnaura and celebrations in St Sophia on great feast-days, the promotion of a Patrikios or a Zoste Patrikia involved the full assembly of all the officials. The Chrysotriklinos now took on a more solemn aspect. The emperor wore his crown and sat on the central throne – not a sellion at the side – and the koubikoularioi stood in a semicircle in the apse behind him. Beginning at the curtains before the western doors, the Papias censed the Chrysotriklinos with a thurible, and then censed the emperor. The officials were admitted according to their rank in a series of eight entrées or “curtains,” as they were called, and performed the proskynesis under the eye of the Master of Ceremonies. When all had entered, the candidate was brought in to the emperor and invested in his or her office, whereupon the whole assembly acclaimed the emperor with the shout “Many Years.” (As Orthodox bishops are greeted still today.) Then all went in procession through the old palace, and the emperor and the new Patrikios or Zoste Patrikia were acclaimed at set points by the circus factions. The procession continued to St Sophia, where the new dignitary received communion and the blessing of the patriarch. A Patrikios would then be escorted home by the factions, whereas a Zoste Patrikia would proceed to the Magnaura, where she herself was the object of another ceremony of proskynesis by the wives of imperial officials. She then returned to the lower palace, where, being usually a member of the imperial family, she lived.35

Now, we note here that the actual rite of promotion of a Patrikios or Zoste Patrikia was performed in the Chrysotriklinos. Likewise, foreign envoys were received there to conduct the real business of their visit. But their first audience, as in the case of the Tarsans in 946, was always held with great pomp in the Magnaura and followed by an itinerary through the old palace fitted out to impress them.36 As in the promotion of a Patrikios or Zoste Patrikia, however, these old buildings served as little more than a ceremonial backdrop on the way from the lower palace to St Sophia or the Magnaura. (One thinks of the antique architectural elements in the background on icons.) The same is true even on great feasts such as Easter, Christmas and Pentecost, when the emperor went in a grand procession, or  , to Hagia Sophia, though every effort was made on these occasions to bring the old palace back to life.37 Very early in the morning all the paraphernalia – the Great (processional) Cross of St Constantine, the Rod of Moses, the Roman sceptres, the ptychia (whatever they were!), and all the rest – most of which were now kept in the Treasury beside St Theodore’s or in the Theotokos of the Pharos, were taken out and set up in what was apparently their traditional places in the old palace. The imperial crown and vestments were also sent up from the lower palace and laid out in the Octagon beside the old Koiton on the courtyard of the Daphne. On this day the lower palace was not opened as usual but all the imperial officials and the circus factions went directly, in their parade clothes, to set points in the old palace along the itinerary to be followed by the emperor. The most important stops were the Augusteus, where the servants of the Chrysotriklinos and the Company of guards acclaimed the emperor; then St Stephen’s church beside the hippodrome, where the emperor revered the Cross of St Constantine; then the Octagon, where the emperor was vested and crowned for the feast; then back through the Augusteus, where the Logothete was waiting to perform the proskynesis; then to the porch of the Augusteus called the Golden Hand, where the emperor received the proskynesis of the magistroi and other high officials; then across the Onopodion for the proskynesis of the Drungarios of the Fleet; then to the Consistorium where another cross of Constantine and the Rod of Moses were set up and the Protasekretis and imperial notarii were waiting; then through the porticoes of the Candidati, the Exkoubita and the Scholae, where the emperor was acclaimed in Latin – now generally unintelligible – by the imperial guards who bore as many of the ancient banners and standards as could be kept in repair.38 Next came the Tribounalion, where the emperor was acclaimed by the circus factions. Then he proceeded through the Propylaion of the Holy Apostles to the Chalke Gate for more acclamations by the factions; and from there he went to St Sophia for the liturgy.

, to Hagia Sophia, though every effort was made on these occasions to bring the old palace back to life.37 Very early in the morning all the paraphernalia – the Great (processional) Cross of St Constantine, the Rod of Moses, the Roman sceptres, the ptychia (whatever they were!), and all the rest – most of which were now kept in the Treasury beside St Theodore’s or in the Theotokos of the Pharos, were taken out and set up in what was apparently their traditional places in the old palace. The imperial crown and vestments were also sent up from the lower palace and laid out in the Octagon beside the old Koiton on the courtyard of the Daphne. On this day the lower palace was not opened as usual but all the imperial officials and the circus factions went directly, in their parade clothes, to set points in the old palace along the itinerary to be followed by the emperor. The most important stops were the Augusteus, where the servants of the Chrysotriklinos and the Company of guards acclaimed the emperor; then St Stephen’s church beside the hippodrome, where the emperor revered the Cross of St Constantine; then the Octagon, where the emperor was vested and crowned for the feast; then back through the Augusteus, where the Logothete was waiting to perform the proskynesis; then to the porch of the Augusteus called the Golden Hand, where the emperor received the proskynesis of the magistroi and other high officials; then across the Onopodion for the proskynesis of the Drungarios of the Fleet; then to the Consistorium where another cross of Constantine and the Rod of Moses were set up and the Protasekretis and imperial notarii were waiting; then through the porticoes of the Candidati, the Exkoubita and the Scholae, where the emperor was acclaimed in Latin – now generally unintelligible – by the imperial guards who bore as many of the ancient banners and standards as could be kept in repair.38 Next came the Tribounalion, where the emperor was acclaimed by the circus factions. Then he proceeded through the Propylaion of the Holy Apostles to the Chalke Gate for more acclamations by the factions; and from there he went to St Sophia for the liturgy.

For state receptions in the Magnaura, imperial officials went directly at the first hour of the morning to the Magnaura, and the emperor went privately  as he always did when not taking part in a formal procession, through a system of corridors which brought him up from the palace to the Magnaura.39 After such a reception or after the liturgy in St Sophia, the emperor normally returned to the palace privately through the corridors, whereas the officials and foreign guests who were invited to dine made their way to the palace through the old buildings on the upper terrace. By the tenth century banquets were almost always held in the Ioustinianos or the Chrysotriklinos, where we find the only mention of kitchens in the De ceremoniis.40 On special occasions banquets might be accompanied by the choristers of St Sophia and the Holy Apostles, who stood behind the curtains of the side vaults of the Chrysotriklinos. The playing of organs marked the entry of the various courses of the meal.41 On great secular holidays there might also be a ballet, either before the banquet in the Sigma-Triconchus complex on the lower terrace or in the Chrysotriklinos during the meal. On each of the twelve days of Christmas, however, ancient custom was preserved and banquets were held in the Triklinos of the Nineteen Couches reclining in the Roman style.42

as he always did when not taking part in a formal procession, through a system of corridors which brought him up from the palace to the Magnaura.39 After such a reception or after the liturgy in St Sophia, the emperor normally returned to the palace privately through the corridors, whereas the officials and foreign guests who were invited to dine made their way to the palace through the old buildings on the upper terrace. By the tenth century banquets were almost always held in the Ioustinianos or the Chrysotriklinos, where we find the only mention of kitchens in the De ceremoniis.40 On special occasions banquets might be accompanied by the choristers of St Sophia and the Holy Apostles, who stood behind the curtains of the side vaults of the Chrysotriklinos. The playing of organs marked the entry of the various courses of the meal.41 On great secular holidays there might also be a ballet, either before the banquet in the Sigma-Triconchus complex on the lower terrace or in the Chrysotriklinos during the meal. On each of the twelve days of Christmas, however, ancient custom was preserved and banquets were held in the Triklinos of the Nineteen Couches reclining in the Roman style.42

Another part of the old palace where particularly ancient ceremonies persisted was the Kathisma on the hippodrome. There are six lengthy chapters in the De cerimoniis which describe in detail the procedure for races and the appearance of the emperor on such holidays as the anniversary of the City on 11 May.43 These chapters contain precious information taken from much older sources. But again, we must be wary of antiquarianism. For our present purposes, the description of the races put on – or, we might say, staged – for the Tarsans in 946 is much more telling. Here again, as in ceremonies elsewhere which have nothing to do with the hippodrome, we see the circus factions reduced to a purely ornamental function as chanters of acclamations and dancers. Moreover, the races themselves appear as little more than another pretext for the extravagant display of costume; there is a total disregard for sport, equal honours being given to the winning and the losing faction.44 One can only wonder what the guests made of these races! All this would suggest that the hippodrome, once a place where the ruler confronted the populace and the factions took a live interest in the races and issues of the day, had also become, by the tenth century, a sort of museum piece, with stylized ceremonies repeated at set dates in the year and on special occasions.45 But whatever the nature of the ceremonies of the hippodrome, the fact that the Kathisma was included within Nikephoros Phokas’ walls in 969 proves their continuity. The case is less certain with other ceremonies in the old palace described in the De cerimoniis. Imperial coronations are said to commence in the Augusteus, marriages in the church of St Stephen beside the hippodrome and the lying in state for funerals in the Triklinos of the Nineteen Couches; the promotion of a Caesar is also placed in the Nineteen Couches, and that of a Magistros in the Consistorium.46

But, as we have already seen, even if the Magistroi were still promoted in the hall where the canopy stood, the name of the Consistorium and its original function had been forgotten, and the ceremonies there, with furnishings brought from the lower palace, must have been very artificial. Likewise, one wonders how long Constantine VII’s restoration of the Nineteen Couches from a state of dilapidation lasted.47 Indeed, can we even be sure that ceremonies were still performed in the old palace at all? The only contemporary coronation described in the De cerimoniis is that of the same Phokas in 963. This, too, is a splendid example of antiquarianism. Parts of these ceremonies were copied from the description of the coronation of Leo I in 457 by Peter the Patrician – it is in fact because of this borrowing that the excerpts from this author were included in the De cerimoniis.48 Phokas’ coronation began, as that of Leo had done, with acclamations by the factions before the Golden Gate outside the city, followed by a triumphal entry through the Golden Gate. Proceeding along the Mese, or main street of the city, amidst the acclamations of the populace, Phokas went to St Sophia for coronation by the patriarch. Unfortunately, the end of this chapter is lost in the Leipzig manuscript of the De cerimoniis, and unless it is discovered in the palimpsest, we shall never know whether there were also ceremonies in the old palace.49 However, it is a curious coincidence that Phokas chose not to commence his reign in the old palace, much of which his walls would soon destroy, but preferred instead the Golden Gate which, we now know, was redecorated as a triumphal arch in this same period.50

Phokas’ activity provides us with a good example for the conclusion of our survey of Byzantine ceremonial and the palace. A hundred years later, the historian Skylitzes considered Phokas a destroyer because his walls wrecked many artworks, that is, buildings of the old palace.51 But nevertheless, Phokas acted in the best Byzantine tradition: even in destroying certain old traditions he replaced them with other, long-obsolete usages which better served his present – in this case military – aims. Such conduct is typical of De cerimoniis and of Byzantium in general: all new measures had to be presented after old models. And here we come back to the distorting mirror.

NOTES

* A slightly different version of this chapter appeared under the title “The Great Palace as Reflected in the De Ceremoniis,” in Bauer 2005b: 47–61. Cer. refers to the two versions of the De cerimoniis listed below as Reiske 1829–30 and Vogt 1967.

1 About these two manuscripts, Lipsiensis I, 17 and Chalcensis 133 (125) + Vatopedensis 1003, see most recently Featherstone et al. 2005.

2 Cer. I, Preface, I, pp. 1–2 Vogt and Cer. II, Preface, 51616–51718 Reiske.

3 Cer. I, p. 29–14 Vogt.

4 The most important studies on the palace based on the De cerimoniis and other texts are still Beliaev 1891; Ebersolt 1910; and Guilland 1969, I; and most recently Bolognesi 2000; Bardill 1999 and 2005.

5 Mango 1974.

6 Chapters from Peter the Patrician: Cer. I 93 (84), 104 (95) p. 38623, 4339 Reiske.

7 Kletorologion = Cer. II 52, ed. Oikonomides 1972: 81–235.

8 For the localization of the Chrysotriklinos on the lower terrace, see Mango 1997: 45–6.

9 On the restricted use of the term  see Bolognesi Recchi Franceschini and Featherstone 2002. “Sacred Palace”: e.g. Cer. I 1, I p. 1630 and 2821 Vogt; I 33 (24), I p. 1275 Vogt; II 9 p. 5404 Reiske; II 12 p. 55013 Reiske; “Sacred Koiton”: e.g. Cer. I 1, I p. 1710 Vogt.

see Bolognesi Recchi Franceschini and Featherstone 2002. “Sacred Palace”: e.g. Cer. I 1, I p. 1630 and 2821 Vogt; I 33 (24), I p. 1275 Vogt; II 9 p. 5404 Reiske; II 12 p. 55013 Reiske; “Sacred Koiton”: e.g. Cer. I 1, I p. 1710 Vogt.

10 One entered the palace directly from the Regia, the continuation of the Mese running beside the Augustaion: Cer. I 100 (91) p. 41513–14 Reiske.

11 On the topography of the upper palace see Bardill 2005: 7–23.

12 When John “the Fat” Komnenos revolted in 1200 he first found his way to the palace barred at the “dwellings of the axe-bearers,” namely the Scholae beside the Chalke. Then, having gone under the seats of the hippodrome to reach the gate of the Karea beneath the Kathisma, he had to break this latter down and overcome those guarding it: Heisenberg 1907: 248–259.

13 For the walls of Nikephoros Phokas, see Mango 1997: 42–6 and his fig. 5. We have marked them in our Figure 13.1.

14 According to Theophanes Continvatus 1838: 142. 19–22, Theophilos even had the everyday procession (about which see below) transferred to the Triconchus. There is no mention of this in the De cerimoniis, where the Sigma and Triconchus are mentioned only as the emperor passes on his way to the old palace e.g. Cer. I 19 (10), I p. 65.15–21 (Vogt), or as the setting for ballets and acclamations in honour of the emperor on special feast-days, e.g. Cer. I 75 (66), II p. 10620–10824 Vogt; Cer. II 18 pp. 6003–6031 Reiske. The most informative passage for the Nea is Cer. I 28 (19), I p. 10820–6 Vogt, where we see that one went down a stairway from the terrace of the Chrysotriklinos and turned right to reach the narthex of the Nea; but there is nothing about the church itself.

15 Cer. II 15 pp. 5738–9, 57813–14, 58411–12 and 5957–8 Reiske. For the date of the later redactor’s work, see Featherstone 2003: 243–4, and 2004 passim.

16 E.g. curtains of the Chrysotriklinos hung in the Consistorium: Cer. II 15 = p. 5739–11 Reiske; chandeliers from the Nea hung in various buildings (on chains also brought from elsewhere): pp. 5711–2, 18–19, 5724–5, 13–14, 18–19, 5734 Reiske; archway in the Tribounalion blocked off with silk hangings: p. 58311–12 Reiske. On this question see Bauer 2005a: 162.

17 For a recent ideological interpretation of the various places and modes of the emperor sitting on the throne, see Dagron 2003b. On the “throne of Solomon” see Berger 2005: 68.

18 For these parallels see Featherstone 2005: 847–8.

19 Cer. II 15 pp. 58015–18, 58112–16 Reiske and II. 1 passim.

20 Cer. II 15 pp. 51918–5201 Reiske.

21 For these and other details of the side vaults, see Featherstone 2005: 848–51.

22 As during the celebration of the Broumalia: Cer. II 18 p. 6033–6 and 7–9 Reiske; and after the banquet for Olga of Russia: Cer. II 15 p. 59716–5982 Reiske.

23 Cer. I 1 p. 5181–52218 Reiske is about the everyday procession on weekdays; Cer. II 2 pp. 52220–52515 Reiske on ordinary Sundays.

24 For the topography of the Covered Hippodrome and the other buildings involved in the daily opening of the palace, see Bolognesi Recchi Franceschini and Featherstone 2002: 39–44.

25 For the salutatio, see Winterling 1999: 117–38, and esp. 117–18 on the Cottidiana Officia. On ordinary Sundays the Magistroi and Patrikioi are mentioned together with the Drungarios of the Fleet: Cer. II 2 p. 52312–13 Reiske.

26 Opening of the  Cer. II 1 p. 5198 Reiske; Logothete waiting there: p. 5206–7 Reiske. There is also mention of old bureaux near SS Sergius and Bacchus, but only as a place through which the emperor passes on his way to that church; they were apparently disaffected: Cer. I 20 (11), I pp. 7914–15 and 8023–4 Vogt.

Cer. II 1 p. 5198 Reiske; Logothete waiting there: p. 5206–7 Reiske. There is also mention of old bureaux near SS Sergius and Bacchus, but only as a place through which the emperor passes on his way to that church; they were apparently disaffected: Cer. I 20 (11), I pp. 7914–15 and 8023–4 Vogt.

27 The only exception is on the occasion of the birth of a son to the emperor, when the wives of imperial officials were admitted to the empress’s Koiton to see the mother and baby, under golden bedclothes, and present their gifts: Cer. II 22 p. 6186–18 Reiske.

28 One thinks of the throne on which the Gospel is placed up to the present day, after the manner of the  in the audience hall of the Ecumenical Patriarchate in Istanbul.

in the audience hall of the Ecumenical Patriarchate in Istanbul.

29 See Winterling 1999: 29–32

30 All these notes are included in the chapter on the weekday procession: Cer. II 1 pp. 52012–52218 Reiske.

31 Sunday banquet-roll read out by the Artoklines: Cer. II 2 p. 5259–11 Reiske. About the  and seating at banquets, see Oikonomides 1972: 28.

and seating at banquets, see Oikonomides 1972: 28.

32 E.g. on the feast of St Basil (1 January) the liturgy was celebrated in the Theotokos of the Pharos with a banquet afterwards in the Chrysotriklinos: Cer. I 33 (24), I 1271–21 Vogt.

33 Birthday: Cer. I 70 (61), II pp. 86–7 Vogt; Broumalia: Cer. II 18 pp. 599.22–607.14 Reiske.

34 Strategos: Cer. II 3 pp. 525–8 Reiske; koubikoularios: Cer. II 25 pp. 624–7 Reiske.

35 Patrikios: Cer. I 57 (48), II pp. 51–60 Vogt; zoste patrikia: Cer. I 59 (50), II pp. 63–6 Vogt.

36 The Tarsans and the Daylamite (Sayfaddawla) and Olga of Russia were all received first in the Magnaura: Cer. II 15 pp. 5831–58424, 59318–21, 58416–5955 Reiske; the Tarsans and Olga were then received subsequently in the Chrysotriklinos: pp. 58615–58814 and 59617–20 Reiske (the Chrysotriklinos is not named here, but Olga is summoned from the adjoining Kainourgion where she had been waiting). (Translation Featherstone 2007.) On the reception of the Tarsans see Bauer 2005a: 154–62.

37 The very first chapter of the De cerimoniis is devoted to this grand procession: I 1, I pp. 3–28 Vogt.

38 Latin acclamations for the feast: Cer. I 1, I p. 819 Vogt. The fossilized and corrupt nature of this ceremonial Latin is clear from the examples preserved in the De cerimoniis, e.g. the acclamations of the koubikoularioi at Christmas: Διθ ...  Cer. I 32 [23], I p. 12528–31 Vogt. According to the inventory of banners etc. kept in the Church of the Lord beside the Consistorium – evidently a sort of chapel of the adjacent Exkoubita, Candidati and Scholae of the old palace – twelve of the eighteen standard-holders had been repaired in the Fourth Indiction (AD 946), and the other six were out of repair: Cer. II 40 p. 6413–5 Reiske.

Cer. I 32 [23], I p. 12528–31 Vogt. According to the inventory of banners etc. kept in the Church of the Lord beside the Consistorium – evidently a sort of chapel of the adjacent Exkoubita, Candidati and Scholae of the old palace – twelve of the eighteen standard-holders had been repaired in the Fourth Indiction (AD 946), and the other six were out of repair: Cer. II 40 p. 6413–5 Reiske.

39 Order for receptions in the Magnaura: Cer. II 15 pp. 56615–57010 Reiske.

40 The door to the kitchen opened into the adjoining Lausiakos: Cer. II 1 p. 5193–4 Reiske.

41 On the function of organs as “givers of signals” within court ceremony see Berger 2005: 66.

42 Christmas: Cer. II 52 pp. 17523–1854 Oikonomides. The banquet for the Daylamite (Sayfaddawla) was also held in the Nineteen Couches “after the manner of Twelfth Day”: Cer. II 15 p. 5943–5 Reiske.

43 New edition of the chapters on the hippodrome (I 77 [68]–82 [73]) by Binggeli et al. 2000.

44 Description of the costumes of the factions, choristers from St Sophia and the Holy Apostles and hippodrome employees fills most of the section on these races: Cer. II 15 pp. 58819–59011 Reiske; “for the sake of display before the Saracen envoys,” the emperor commanded, in contradiction to the “old order,” that the losing faction should also accompany the winner in the victory celebrations: Cer. II 15 p. 59011–15 Reiske.

45 About this ceremonialization of the races, see Mango 1981: 344–50.

46 Coronations of both emperor and empress begin in the Augusteus: Cer. I 47 (38), II p. 16 Vogt and I 49 (40), II pp. 113–122 Vogt; marriages in St Stephen’s: Cer. I 48 (39), II p. 64–5 Vogt; lying in state in the Nineteen Couches: Cer. I 69 (60), II p. 841–3 Vogt; promotion of a Caesar in the Nineteen Couches: Cer. I 52 (43), II pp. 269–275 Vogt; of a Magistros in the Consistorium: Cer. I 55 (46), II pp. 4020–4329 Vogt.

47 Cf. Theophanes Continuatus 1838: 44917–4503.

48 Account of the coronation of Nikephoros Phokas in Cer. I 105 (96) pp. 4382–44011 Reiske (borrowings from Peter the Patrician: p. 43910–17 Reiske [cf. Cer. I 100 (91) pp. 41015–41113 Reiske]); cf. Featherstone 2004: 114.

49 There is one folio missing here from the Lipsiensis, and the account breaks off at the beginning of the office in St Sophia (p. 44011 Reiske). Fol. 265 of the Chalcensis part of the palimpsest contains this passage of chapter I, 105 (96) but, alas, it breaks off a few words earlier than in the Lipsiensis, with p. 44011 Reiske. Perhaps the subsequent text will be found in the Vatopedi part.

50 See Mango 2000: 181–6.

51 Cf. Skylitzes 1973: 27579–83.