CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

WHAT IS A BYZANTINE ICON? CONSTANTINOPLE VERSUS SINAI

Bissera V. Pentcheva

We tend to associate the word “icon” with a portrait of a holy figure on wood panel, painted with tempera or encaustic (wax-based medium).1 This brief essay will challenge this established notion and argue for the diversity of meanings of eikon in Byzantium and for the site-specific character of icons.2 In our modern understanding of the history of eikon we have sought its origins in the Egyptian painting tradition of panels of the gods or of portraits of the deceased drawn on wood boards or cloth and colored with tempera or encaustic. The evidence for this practice emerges in the Hellenistic period but continues throughout the late Roman imperial times.3 Similarly, we have looked for answers for the origins of icons in the rise of the cult of saints and pilgrimage in Palestine.4 Earthen or lead tokens from the Holy Land and Syria with the imprinted portrait of the saint (Figure 21.1), or an image of the architecture or of the hallowed event that took

Figure 21.1 Clay token of St Symeon the Younger, after Vikan 1982: fig. 22.

place at the site, gave the faithful a continual return to the sacred source of power.5

Rather than our modes equating with an “image”, “eikon” in Byzantium in the period before Iconoclasm meant enactment, a descent of spirit in matter. The pilgrims’ tokens and the cult of the stylite saints (from stylos, column, for they spent long years standing on a column) enabled the establishment of this essentialist understanding of eikon as body/matter penetrated by the Holy Pneuma:

An eikon of God is the human being who has transformed himself according to the image (eikon) of God, and especially the one who has received the dwelling (enoikesin) of the Holy Spirit. I justly give honor to the icon of the servants of God and proskynesis to the house of the Holy Spirit.6

With these words the eighth-century Pseudo-Leontios of Neapolis identified as George of Cyprus explained eikon as human body receiving the Spirit; the enoikesis (dwelling) of the Spirit in matter created the true eikon.

How was this enoikesis manifested? In a threefold manner: first through the corporeal example of the stylite saints; second through the images and inscriptions on the tokens produced and distributed at these sites; third through the practice of burning incense on top of them. Tokens from the sanctuary of St Symeon the Stylite the Younger (521–92) at the Magic Mountain (today in south-western Turkey) depict the saint standing on his column (Figure 21.1). The inscription running along the rim presents the word “eulogia,” blessing.7 This token served as a magical amulet, encapsulating the process of embedding spirit in matter, known as empsychosis (en-, in, psyche-, soul, spirit). Its inscription and images are characteres, incised and imprinted on the surface. Character comes from charatto, which means “to cut,” “to engrave,” “to incise; ” it is also associated with magic, denoting the process of imbedding spirit in matter.8 Their power was activated when incense was burned on top of them.9 The wafting smell of this thymiama marked the presence of the Holy Spirit.10 It is important to recognise how this ritual practice of burning incense transformed the clay eulogiai into conduits of divine pneuma.

EIKON DURING ICONOCLASM: THE FORMATION OF THE CONCEPT OF AN “IMAGE”

Byzantine Iconoclasm (726–843) challenged this understanding of eikon as a site of pneuma dwelling in matter. So far, we have viewed this crisis through the prism of the sixteenth-century Reformation, imagining the destruction of churches, murals, mosaics and panels. By contrast, the Byzantine phenomenon appears to have been more of a process of narrowing of the meaning of eikon: from an identification with a body (an essentialist theory manifested in the stylite cults) to an eikon understood as the imprint – typos – of visual characteristics on matter (a formalist, nonessentialist theory). At the core of this non-essentialist definition stood the pilgrims’ tokens.

Our modern term “iconoclasm” is a misnomer, stemming from our own narrow identification of icon with a painted panel. The Byzantine conflict, by contrast, mostly expressed itself as debate on the meaning of the term eikon. The “opposition” party was frequently called eikonomachoi, “debaters,” not destructors of icons. Neither party denied the validity of eikones, yet each defined their identity in different terms. For the eikonomachoi of the reigns of Leo III and Constantine V (717–75), a true eikon was only the Eucharist: matter penetrated by the Holy Spirit in a sacerdotally administered empsychosis of the Holy Spirit.11

By contrast, for the early eikonophiloi “icon” was all matter receiving the Spirit, without the need of sacerdotal sanction. For them such enoikesis became possible though the Incarnation of Christ. Thereby, all matter became sanctified through this descent of Pneuma. John of Damascus (born in the late seventh century, died in the 750s) formulated the clearest expression of this position in his Oration I contra imaginum calumniatores orationes tre:

Of old, God the incorporeal (asomatos) and formless (aschematistos) was never depicted (eikonizeto), but now God has been seen in the flesh and has associated with human kind, I render in icon (eikonizo) the material entity of God seen by humans. I do not venerate (proskyno) matter (hyle), I venerate the fashioner (demiourgon) of matter, who became matter for my sake and accepted to dwell in matter and through matter worked my salvation, and I will not cease from reverencing matter, through which my salvation worked. I do not reverence it as God – far from it … Therefore I reverence the rest of matter and hold in respect that through which my salvation came, because it is filled with divine energy and grace.12

Already the first sentence juxtaposes the Old Testament God to the New Testament Christ, leading from the formless and incorporeal Godhead, to the materiality of Christ achieved through the Incarnation of the Logos. In this core Damascene theory, the Incarnation justified and validated matter: from relics, liturgical objects, to the Eucharist itself. The icon was envisioned as part of that economy of matter. In rejecting the icon, Christians would reject materiality.

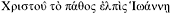

It is this essentialist definition that the eikonomachoi attacked, linking matter/hyle exclusively with the deceit (plane) of pagan figural painting/graphe. In the course of the early ninth century, they gradually centered the identity of eikon on a concrete object; for them it was the cross. The eikonomachoi expressed their position on the new façade of the imperial gate, the Chalke, in 814–15. Here five epigrams stated the new non-essentialist, non-figural identity of eikon.13 The composition consisted of a cross set at the center and five poems: one placed at its foot and four others in the four cardinal points (Figure 21.2). In this cross-wise configuration, the epigrams repeated the shape of the stauros and aggressively argued through spatial arrangement and acrostics that eikon was equivalent to only two forms: (1) graphe understood as “letter” and (2) typos defined as the shape of the cross. In fact, both typos and graphe collapsed in one symbol: the cross composed of letters/acrostic. One epigram of the Chalke is enough to show the forcefulness and clarity of this aniconic theological/political position:

Figure 21.2 A reconstruction of the eikonomachoi façade of the Chalke Gate at 815. B. Pentcheva.

The confessors of God write “Christ” in gold (chrysographousi) according to the prophets’ voice, not relying on the visible things below. Speaking in equal terms (isegoron) is hope and faith in God, as opposed to painting in shadows (skiographon) a recurring deceit (palindromon planen).

With those, who trample upon it, for it is hated by God, being in agreement, the ones carrying the crowns, raise on high the Cross in a pious judgment.14

Written by John the Grammarian (patriarch of Constantinople, 834–43), the poem compares Logos and graphe. Christ as the Logos could only be expressed through the text and materially through the cross. Painting, marred by deceit (plane) and created through the art of shadows (skiagraphia) and application of color, has failed to convey the divinity. To speak of God requires equal terms (isegoroeo), which is only offered by language, the word and the logos. Anything less than the word will compromise the divinity of the prototype. So, in using only the word, the eikonomachoi present an example of faith and hope.

The first, middle and last letters of each line of the first epigram are arranged to form the following phrase: the Passion of Christ is the hope of John.15 This phrase strengthens John’s position that the cross is the only legitimate figure, offering the true path to Salvation. Not only the words, but also their visual position in space form the shape of this cross (Figure 21.2). The words “Christ,” “Passion” and “John” are all composed of letters placed in vertical columns, intersected by the horizontal line: “Hope.” The poem thus “figures” the cross by means of both content and form. Even more so, it depicts the cross entirely through letter configurations/acrostic. The Logos-graphe has thus become, or better, has subsumed, the eikon, becoming the enfleshment of divinity in matter: an aniconic manifestation of the Incarnation.

The eikononophiloi responded to this letter-centered definition of eikon with a similar non-essentialist model, collapsing eikon with graphe, and identifying both with typos understood however not just as the cross, but as the imprinted image: an intaglio stamped on matter. Theodore Soudites (759–826), the abbot of the Stoudios monastery, a writer and intellectual, gave the most expressive summary of these ideas in his Antirrheticus I–III discourses.16 Like the iconoclast typos, which signified the generic form of the cross and bore formal likeness to the Life-giving Cross, so too did the icon according to the Stoudite definition acquire veneration because it bore the imprint (typos) of Christ’s likeness (homoioma) and form (morphe): a relationship with the prototype established on the basis of form, not essence.17

Likewise, as much is said about the representation (typos) of the cross as about the cross itself. Nowhere does Scripture speak about figure (typos) or image (eikon), since these have the same meaning, for it is illogical to expect such a mention, inasmuch as for us the effects share in the power of the causes. Is not every image (eikon) a kind of a seal (typos) bearing in itself the proper appearance of that after which it is named? For we call the representation (aposphragisma, “imprint”) “cross” because it is also the cross, yet there are no two crosses, and we call the image (eikon) of Christ “Christ,” yet there are no two Christs (Antirrheticus I, sect. 8, trans. Roth, underlined words my addition).18

Theodore opened the discourse with the equivalence of typos and eikon. Both the typos as cross and the typos as eikon he defined as imprints and sealings of a prototype. In appropriating typos for his iconic theory, Theodore Stoudites extracted the word from its iconoclast, non-anthropomorphic signification. He thus built his theory on the basis of the iconoclast typos, yet he adapted it to mean the iconophile eikon: a figural representation.

A habitual engagement with mechanical production practices informed Theodore’s theoretical model. The making of a seal stood at the core of his argument of equivalence of typos and eikon. Seals were widely used in the household to protect goods or seal written missives.19 All one needed was a set of iron pliers and a lead seal blank. The pliers had an intaglio relief incised on the valves. Once the lead blank was softened on the wick of a burning candle, it was placed between the valves. Then the pliers were drawn shut by the hit of a hammer. The negative intaglio impressed itself on the molten surface of the lead (Figure 21.3).

For Theodore, likeness was predicated and transmitted on the basis of mechanical reproduction rather than imitation. The icon was thus a seal (sphragis) and typos,

Figure 21.3 Iron pliers and a lead seal with the image of St Nikolaos, after Zacos and Veglery 1972: pl. 4.

made by the imprint of character on matter. As such eikon assimilated the iconoclast typos:

For what closer comparison has the icon of Christ than the typos/copy of the cross? For through its likeness (emphereia) the icon [refers back] to the prototype. By analogy we call “icon” of the life-giving cross the copy (ektypoma) [of the cross], so too [we call] the imprint (ektypoma) of Christ his “icon.” For eikon etymologically means “to look like” (eoikos). And to “look like” is likeness (homoion), and likeness is perceived, spoken of and seen in the typos [copy of the cross] and in the eikon.20

Theodore argued that the icon was not just equivalent to the typos of the cross, but being an imprint of likeness, it directly led back to the prototype. Even more so, eikon allegedly derives from eoikos, so both phonetically and semantically the word “icon” manifested likeness. And it is not any type of likeness, but the mechanically reproduced one: the imprinted, sealed resemblance on matter.

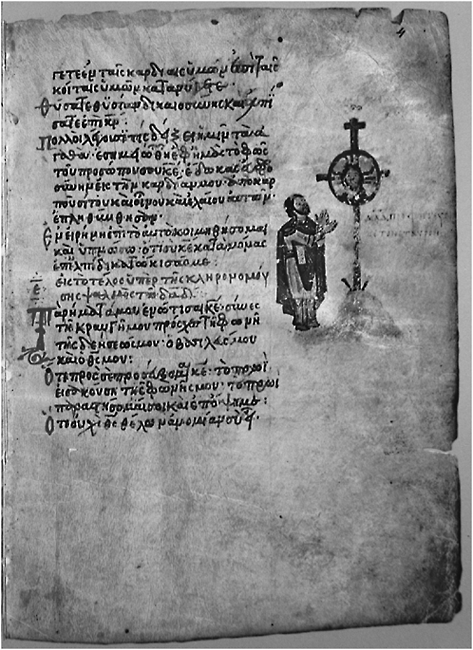

This new non-essentialist theory insisting on the definition of eikon as the imprint of form on matter emerges in the miniatures of the mid-ninth-century Khludov Psalter (Moscow, State Historical Museum, ms. gr. 129, fol. 4) (Figure 21.4). This image shows a medallion icon of Christ set at the center of a cross.21 King David pointing toward it announces: “the light of thy countenance, O Lord, has been imprinted (esimeiothe) on us” (Psalm 4:7).22 The Davidic words have become images, which proleptically configure the coming of Christ. The prophecy is realized not just through the image of the Cross; it is superseded by the image of the figural icon. The composition negotiates the meaning of the word “semeion”: formerly a synonym for the aniconic (1) eikonomachos’ typos (cross) and (2) sealing (sphragis understood as “blessing gesture”).23 The figure of the cross is now incorporated in the icon of Christ’s face. This visual composition thus argues how the meaning of semeion has become the anthropomorphic ektyposis of Christ’s face.

The composition of this miniature unfolds like a series of imprints: the face imprinted on the icon, the cross stamped on the halo and the medallion embedded in the cross. The viewer falls into a mise-en-abyme of imprints, all of them subsumed in the radiating fiery light of gold. The configuration evokes the new post-843 iconophile Chalke Gate, where the Chalkites icon of Christ dominated the center of the cross.24 This visual program asserted the supersessionist power of the eikon over the cross, celebrating the end of Iconoclasm.

By creating a typos-based theory of the image, Theodore in fact shifted the icon discourse away from the Damascene Incarnational economy. The latter focused on the legitimacy of Christ’s morphe: the visible form (character), and thus answered why representation (graphe) was possible. By contrast, Theodore developed the “economy” of the typos, and thus explained what made the icon legitimate. The Stoudite eikon, by being the product of a double imprint: (1) the character, which resembles a “snow angel” made by the imprint of morphe, and (2) a typos as a sealing of this character on matter, displayed the final, correctly presented through double imprinting physical manifestation of Christ’s morphe.

The eikon as typos, understood as a seal and imprint, firmly established plastic arts (relief) over graphic arts (painting). This change had a profound impact on the

Figure 21.4 Khludov Psalter, Moscow, State Historical Museum, ms. gr. 129, fol. 4, after Shchepkina 1977.

middle Byzantine icon production and appearance. Bas-relief achieved through imprint, engraving, incision, repoussé or enameling took priority over painting. Graphe acquired a dominant meaning as typos and sphargis: an imprinted surface.

ENAMEL, POIKILIA AND MOVING EYES

Enamel best exemplifies this typos-centered theoretical model of eikon. It is a form of imprint made by fire, for its figures are formed of metal paste set in molds (the golden cloisons or the sunken bed of gold) and transformed by fire into a luminous gemlike surface. In the course of the tenth and eleventh centuries, Byzantium became a leader in the production of this medium, creating objects whose splendor of gold, translucency of glass and complexity of workmanship dazzled foreign courts.

These were luxury mixed-media relief icons – poikilai eikones – displaying an array of artistic techniques (enamel, repoussé, filigree) and shifting chameleonic surfaces. The enamel, especially the green one, possessed an iridescence that became manifest in movement, sunlight and under the flicker of candlelight. Through its opalescent appearances, the metal mixed-media icon conveyed a sense of living, breathing matter: the quintessential empsychos graphe (en-, in, psyche, spirit) in Byzantium.25 It acted like fish-scales in ruffled waters playing out a rainbow of colors, or like the incessant, always-changing flame of fire, or the polychromacity of Byzantine porphyreos, whose multiplicity and instability of hues displayed the vortex of stormy seas or gushing blood.26

The Byzantines designated this polymorphity as poikilos or poikilia (diversity): phenomenal effects sensually experienced.27 Poikilia was understood as animation: the spirit present in matter. It is this power of poikilia – the spectacle of changing appearances, polychromacity and opalescence corporeally experienced – that the mixed-media relief icon gathered into one gemlike structure of gold, pearls and translucent glass.

The rise of such luxury relief icons in Constantinople in the tenth and eleventh centuries expressed an aesthetic pursuit for the phenomenal, opposed to pictorial naturalism and painting. The moving diurnal and candlelight across these rich material surfaces create highlights and shadows, giving rise to myriad appearances. The Constantinopolitan mixed-media eikon-typos has a meaning in flux, consolidating and unraveling in the phenomenal world of breathing space, flickering and moving light, and drafts of air. It is the human voice and movement that bring about animation in the icon. With each gesture, or word, or simple breath, the faithful causes the flame of candles to flicker, bringing about the shimmering splendor of the gold and the dance of shadows across the complex surfaces of the image. It is this dynamic poikilia that endows the object with life, transforming it into an empsychos graphe, both literally and physically in-spirited.28

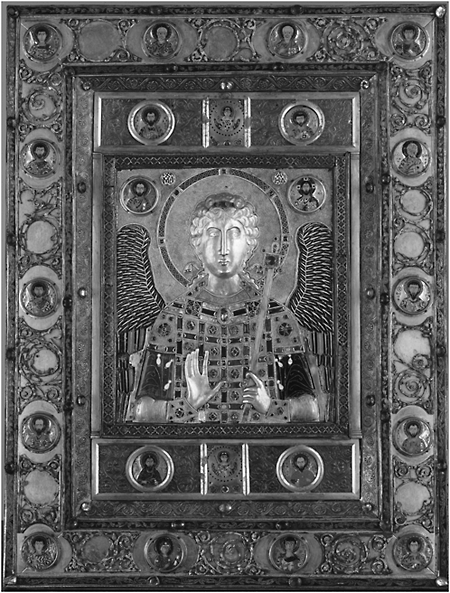

The face of the bas-relief icon Archangel Michael kept at the treasury of San Marco, Venice performs this poikilia of shifting appearances (Figure 21.5).29 If a candle is brought and moved left and right, up and down in front of the image, the head changes expression. His eyes, formed in repoussé gold, capture the flicker of light in bright, shining accents. His burning gaze rotates as the candlelight moves, creating the sense of living eyes, searching and following the viewer.30 Life – psyche and pneuma – emanates from this animated gaze.

Moreover, the repoussé bas-relief face presents a fiery vision and enacts what seeing meant for a Byzantine audience.31 According to the prevalent extramission model, the eye sends fiery rays which touch the surface of objects and return back carrying the memory of this tactile experience.32 Yet, not only the eyes of the

Figure 21.5 Mixed-media relief icon of the Archangel Michael, Venice, Treasury of San Marco. Art Resource, New York; photo: Cameraphoto.

beholder “touch/kiss” the rich surfaces of these icons, but the radiant enamel or repoussé eikones act like this very eye – casting nets, pulling in the spectator in the luminous play of their shimmering and reflective surfaces.

I call this quality of the mixed-media poikile eikon “performative,” because while being apsychos graphe (a- without, psyche, spirit), it gives a performance of empsychosis, engages the phenomenal through its surfaces and acquires life by proxy, by reflection and by skiagraphia (the play of spatial shadows). It is the potential for change lurking in the object. The performative icon is thus firmly tied to its space, engaged in a symbiosis, interaction, or to use the Byzantine Eucharistic terms, it participates (metecho and metalambano) in its environment.33

THE RETURN TO GRAPHE AS PAINTING

Inanimate (apsychos graphe) matter, lacking presence, should only be given honorable/relative veneration (timetikos/schetikos proskynesis). In prioritizing exteriority and phenomenal poikilia, the middle Byzantine luxury mixed-media eikones typoi precipitated a crisis of misapplied latreutikos proskynesis (adoration) leading to a new iconoclast outbreak 1081–95. This Komnenian Iconoclasm faced the problem of confusing presence effects for divine presence. Yet, the true cause for the ensuing iconoclast crisis lay elsewhere, in the imperial appropriation and melting of church treasuries.34

An opposition headed by Leo, the bishop of Chalcedon, arose against this policy. By pairing iconic matter (eikonike hyle) with the character in the definition of eikon, Leo ensured the inalienability of the material substance and thus the inviolateness of the icon itself as an object.35

Icon is said in the case of Christ, the Virgin, the venerable angels, and all saints and holy men to be both, i.e., the matter (hyle) and the character imparted in them. The hypostaseis imparted in the icons of all the others [Virgin, angels and saints] are to be venerated relatively and honorably, and be kissed.36

And again:

For always the iconic matter (eikonike hyle) is matter dedicated (anatetheimene) to God, as a divine dedication [votive gift] (anathema), and the character of Christ is always Christ and God; who is contemplated through the mind yet being circumscribed (kechorismenos) in matter.37

According to Leo, matter, eikonike hyle, is what makes the character/form visible; it is inalienable, a material necessity for the existence of eikon. As a votive gift, an anathema, it is also protected from attempts at expropriation.38

Leo’s insistence on eikonike hyle as part of the definition of eikon was immediately challenged by the imperial party. The semeioma of 1095 proclaimed that icon was just “likeness” (homoioma):

And again the emperor asked: “What do you call icons: the iconic material substances (eikonikas hylas) or the likenesses (homoiomata) made visible (phainomena) in them?” And every one responded: “The likenesses (homoiomata) made visible in the material substances (hylais).” Should the likeness (homoioma) of Christ, which is made visible in matter receive adorational (latreutikos) proskynesis?” And they said “No!” And the emperor said: “This is the truth what you have just said.” Then the bishop of Claudiopolis said: “Some say that the icons do not partake in divine grace.” The emperor together with everyone else responded: “Anathema to the one who says that, for the icons partake in divine grace, yet they are not of the same substance (homophyeis) as their prototypes.” … The emperor asked: “The likeness of Christ represented (graphomenon) in matter, is this his divine nature (theia physis)?” Every one responded: “No, for divine nature (theia physis) is beyond representation (aperigraptos).”39

The imperial definition narrowly limited the icon to just the likeness (homoioma), excluding the material in which it was fashioned. By excising the eikonike hyle from what makes an icon, this statement denied the role of matter. By shifting the discourse from imprint (typos) to likeness (homoioma), the new definition made the icon primarily concerned with the reproduction of similarity, not with a spectacle of phenomenal poikilia. In clinching icon to likeness, the Komnenian formulation eventually cleared the path to pictorial naturalism.

Connecting icon production to the medium of painting, the Komnenian definition established the inalienability of likeness. Painting on wood panels cannot be recycled like the metal relief icons, hence painting has an advantage over the mixed-media typoi. At the same time, the metal revetments, made of gold and silver, could easily be taken down from a painted icon. As simple anathemata, human gifts, these metal sheaths no longer carried the likeness of the holy figure. In separating likeness from the precious metals and gems, the Komnenian interpretation of eikon slowly ensured the move away from graphe as typos to graphe as painting. This stimulated the production of painted icons with metal revetments, which in turn secured the continued state access to these metal deposits, while preserving the inviolateness of the image.40 The metal-revetted painted icons rose in fulfilment of this neat Komnenian separation of eikon from its material anathemata. The Palaiologan production preserves many such examples of neatly paired homoioma with anathema, such as the late thirteenth-century icon of the Mother of God Psychosostria (Savior-of-Souls) from Ohrid, Macedonia (Figure 21.6).

SINAI AND THE DOMINANCE OF THE PAINTED PANEL

In contrast to Constantinople, Sinai, which lay outside the Byzantine borders after the mid-seventh century, never experienced the rise of luxury metal relief icons. Instead it manifests a continual and stable understanding of eikon as painting. Sinai purposefully created a very place- and medium-specific definition of icon, as a site of optical experience theophany and receptor of divine orders.

Rocks of pink granite, sand, dry winds and dazzling light shape the arid landscape of Sinai. Here, paradoxically, visions of God were projected onto the barren land. At Sinai Moses saw the burning bush and received the command to lead the Israelites

Figure 21.6 Painted icon with silver-gilt-enamel revetment of the Mother of God Psychosostria, Ohrid, Icon Gallery. Art Resource, New York; photo: Erich Lessing.

out of Egypt (Exodus 3:1–10). Here again he climbed Mt Sinai to receive the tablets of the law (Exodus 24), and when he came down the mountain he condemned the Israelites for their idolatrous worship of the golden calf. Sinai thus became the site of reformed sight and obedience, as defined by the First Commandment:

You shall not make for yourselves any graven image (eidolon), or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water underneath the earth. You shall not bow yourself down to them or serve them.

(Exodus 20:4–5, Deuteronomy 5:8–9)41

The Greek defines the forbidden object as idol (eidolon). The word in patristic Greek refers to images of the pagan gods, destroyed by Christ. As a secondary meaning, it refers to phantom of the mind and ghost. The Latin uses “carving” (sculptilis). It thus emphasizes surface and relief. The same word sculptilis appears again in Psalm 105 (106):19, which again refers to the idolatrous actions of the Jews at Mt Sinai.42 The Latin sculptilis has a Greek equivalent – glyptos. In both the Latin West and the Byzantine East sculptilis/glyptos evoked sculpture: statues or bas-reliefs, images carved by human hand. It is this sculptilis/glyptos that was banned on Sinai.

This emphasis on seeing as an optical, non-tactile experience is strangely mirrored in the actual collection of icons at the monastery. Most panels rely on optical effects of chrysography (highlights marked by the application of gold lines). The collection also does not hold metal relief icons, or ivory and enamel. In addition, no metal revetments for icons are preserved. Last but not least, no miraculous icons feature among the over 2,000 panels. The objects gathered all conform to the definition of eikon as a wooden board with tempera or encaustic images. By rejecting the metal relief icon, and with it tactility of the middle Byzantine Constantinopolitan poikilos typos, Sinai brought out the painted image. The entire collection addresses itself as a site of optical experience, shunning glyptos and asserting graphe as painted eikon.

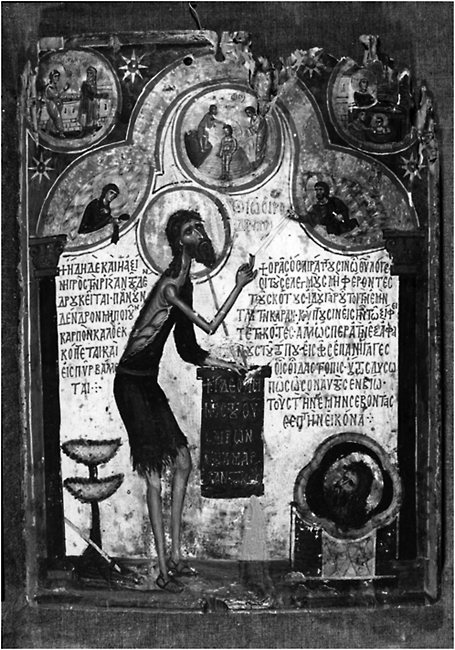

This programmatic emphasis on sight, vision and radiance is embedded in the subject matter of the panels, especially the ones produced on Sinai, showing how site-specific the history of the icon was in the Middle Ages. One panel bears out this optical iconic identity: the thirteenth-century icon of John the Baptist (Figure 21.7).43 At first glance, the icon appears quite strange, for none of the figures faces the viewer. John the Baptist is turned to the side, engaged in a dialogue with Christ. The eyes of the Forerunner, however, connect to a different realm: the small centrally placed roundel presenting the scene of the Baptism of Christ. This becomes the signature moment in John’s identity: his prescient sight, recognizing Christ’s divinely human nature and his sacrifice for the sake of humanity. The Baptism roundel is linked on a vertical axis to the purple scroll unfolded in John’s hand: “Look! The lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world” (John 1:29).44

The purple parchment refers to flesh, incarnation and sacrifice; it carries the color of blood. And this sacrificial message is confirmed and strengthened by the word “lamb of God.” The purple scroll also establishes a connection with the severed head of the Forerunner hovering on the surface of the font’s water, represented to the right. Blood and water are intermixed in a vision of sacrifice, which evoke both the decapitation of John the Baptist and the Crucifixion of Christ.

Right above John’s severed head with eyes closed in death stand the last words of a long inscription: “… your holy icon we venerate.” Which holy icon is referred to here? Is it the entire panel, but this problematic for the icon lacks stasis: an arresting gaze. Could it be the severed head? Yet it fails to establish eye contact because its eyes are closed. Or is it Christ and his Baptism, the true icon: the very moment which sets

Figure 21.7 Painted icon of St John the Baptist, Mt Sinai, monastery of St Catherine. Reproduced through the courtesy of the Michigan-Princeton-Alexandria Expedition to Mt Sinai.

in motion the journey of Christ leading to his Crucifixion, Death and Anastasis? The Baptism is indeed the scene of transformation grasped though the power of one man’s divinely inspired sight. John’s seer’s eyes foresaw the coming of the Messiah. The holy icon (septe ikona) is the very vision he saw: the miniature central roundel of the Baptism of Christ.

Emphasis here is placed on seeing, understood as a trajectory leading from the closed eyes of John’s severed head, across the open scroll and his speaking hand, finally to the Forerunner’s upturned face gazing at the vision of salvation: Christ’s Baptism. Given its strong rhetorical stance for divinely inspired sight, this icon fits perfectly into the programmatic defense of theophany as the milestone of Sinaitic religious identity.

The special status of this Baptismal scene is also reinforced by its position; it is set inside the arch in a hallowed, golden ground, and thus separated by the other two medallions, which are placed outside the architectural frame. The iconic scene of the Baptism is connected to the command: “Behold, Look!” (Ide).

Sight is shown as judgment, while hearing is presented as a means to convey and obey divine commands. These ideas emerge in the two long inscriptions. The one on the right starts with the question “Do you see?” and links to the command Ide (behold) written on the purple scroll. The long text continues:

Do you see what they do, O divine Logos, the ones who do not bear the reproach of darkness? For behold those who cover with dirt my head, which they cut off with the sword. But as the ones who restored it from the awful place back to light by means only you know of, for them I beseech you, preserve them in life, for they venerate my holy icon.45

This prayer carries the visceral, abrasive power of John the Baptist; there is no middle ground, the world is divided into those who transgress without repentance, unable to carry the reproach of darkness and those who follow the right path. Death is meted out to the sinful, salvation to the righteous. The icon becomes the site of judgment, for the Forerunner asks Christ to see and thus condemn and punish the evildoers. The axe and the severed head only intensify the sheer anger and fury of John’s speech.

The word “reproach” (elegmos) is laden with meaning, for it refers both to the trial by water (elegmos tou hydatou: Numbers 2:18–31) and to John the Baptist’s washing of the sins of the repentant. The Virgin herself was subjected to this trial by water when Joseph questioned her purity after her encounter with the Archangel Gabriel.

Elegmos/reproach connects the right side of the panel to the left. The left side of the icon forms a visual and textual model for bearing the good fruits of repentance. At the top Zacharias receives the news of the conception of his son, below Mary offers a purple cloth to the Baptist, followed by a quotation from the Gospel (Matthew 3:10) and an image of a tree and an axe. The inscription emphasizes that only the trees bearing good fruit will be spared the axe and fire of destruction:

And even now the axe is laying at the root of the trees – therefore every tree that is not bearing good fruit is to be cut down and thrown into the fire.

(Matthew 3:10)46

Bearing the good fruit is understood as the act of repentance (Matthew 3:8). John the Baptist had ushered the path of repentance through water, inviting humanity to partake in it. Through him “trees” have started to bear good fruit. It is these good offspring who discovered the severed head of the Forerunner. On their behalf, John the Baptist now beseeches Christ to see and to offer them eternal life. “To see” and “to save” become equivalent. The immediate lack of a direct eye contact with any of the depicted figures on this icon thus acquires a deeper meaning, for it suggests the reversal of viewing strategies. Rather than the beholder looking at the panel, it is the panel itself that bears the stamp of the all-seeing divine eye, awoken by the Forerunner’s request to see and mete out judgment: the eye of God at Sinai. Graphe is here understood first and foremost as scripture, only secondly is it translated in figural form. The miniature visualization “reads” like a manuscript illumination, illustrating a text: the word dominates the image.

CONCLUSION

Sinai’s unique collection of painting on wood panels, starting in the sixth century, offers an unprecedented opportunity to study the history of the medieval pictorial tradition. At the same time, it has seduced scholars to equate the Sinai painted panel with the normative Byzantine icon. This has led to our modern identification of eikon with wood panel in tempera or encaustic.

By contrast, Constantinople had a different history of the icon, privileging the mixed-media relief object, the poikile eikon, in the period from the end of Iconoclasm to the late eleventh century. In separating the icon from zographia and in linking it with imprint (typos), the Byzantines raised the relief icon to the highest status. Theirs was a different hierarchy in which the plastic image in metal, enamel, stone and ivory presented the perfect iconic form, performing presence through chameleonic appearances of spatial shadows, radiance and opalescence across complex surfaces.

NOTES

1 Belting 1994.

2 Pentcheva 2006b; Pentcheva 2010.

3 Bierbrier 1997; Walker 1997, 2000; Doxiadis 1995. On the eikones of pagan gods, Mathews 2001.

4 Vikan 2003.

5 Vikan 1982.

6  PG 93:164C, D. Pseudo-Leontios of Neapolis identified as George of Cyprus, eighth century.

PG 93:164C, D. Pseudo-Leontios of Neapolis identified as George of Cyprus, eighth century.

7 Grabar 1958; Elsner 1997.

8 On charatto and magic, Pentcheva 2010: ch. 1.

9 Vita St Symenis Stylitae, ch. 231, vv. 72-3, ed. Van den Ven 1962; Pentcheva 2010: ch. 1.

10 Harvey 2006.

11 Pentcheva 2010: ch. 3.

12

John of Damascus, Contra imaginum calumniatores orationes tre, I, sect. 16, ed. Kotter 1969-88; English trans. Louth 2003: 29.

John of Damascus, Contra imaginum calumniatores orationes tre, I, sect. 16, ed. Kotter 1969-88; English trans. Louth 2003: 29.

13 PG 99: 435-78.

15  PG 99: 436 B.

PG 99: 436 B.

16 PG 99: 327-436. English trans. Roth 1981.

17 Theodore Stoudites, Antirrheticus III, ch. 3, sect. 5: PG 99: 421D.

18  Theodore Stoudites, Antirrheticus I, sect. 8: PG 99: 337C.

Theodore Stoudites, Antirrheticus I, sect. 8: PG 99: 337C.

19 Vikan and Nesbitt 1980.

20  Theodore Stoudites, Antirrheticus II, ch. 23: PG 99: 368B, C. Another English trans. Roth 1981: 57.

Theodore Stoudites, Antirrheticus II, ch. 23: PG 99: 368B, C. Another English trans. Roth 1981: 57.

21 Corrigan 1992 and Shchepkina 1977.

22  Psalm 4:7.

Psalm 4:7.

23 On semeion and sphragis, Reijners 1965: 118-87.

24 Frolow 1963.

25 Pentcheva 2010: ch. 4.

26 Pentcheva 2006b: 643-8.

27 Pentcheva 2006b; Pentcheva 2009.

28 Pentcheva 2010: chs 5-6.

29 Pentcheva, 2006b; Pentcheva 2009, with all the photographic documentation of the icon’s performance.

30 Pentcheva 2010b: ch. 5.

31 Pentcheva 2006b; Pentcheva 2010.

32 Frank 2000b: 98-115; Nelson 2000a; Barber 2007: 94-9.

33 Pentcheva 2006b; Pentcheva 2010.

34 Pentcheva 2009: ch. 7. See also Stephenson in this volume ch. 2.

35 On Leo’s letter to Nikolaos, bishop of Adrianopolis, 1093/4, see Carr 1995: 580-2, Barber 2007: 131-43, with references.

36  Leo’s letter to Nikolaos, bishop of Adrianopolis, 1093/4, Lavriotes 1900: 415, 446.

Leo’s letter to Nikolaos, bishop of Adrianopolis, 1093/4, Lavriotes 1900: 415, 446.

37  Leo’s letter to Nikolaos, bishop of Adrianopolis, 1093/4, Lavriotes 1900: 414, 446.

Leo’s letter to Nikolaos, bishop of Adrianopolis, 1093/4, Lavriotes 1900: 414, 446.

38  Adrianopolis, 1093/4, Lavriotes 1900: 415.

Adrianopolis, 1093/4, Lavriotes 1900: 415.

39  From the Semeioma of Alexios I Komnenos, council of Blachernai 1094/5: PG 127: 971-84, esp. 981A.

From the Semeioma of Alexios I Komnenos, council of Blachernai 1094/5: PG 127: 971-84, esp. 981A.

40 Pentcheva 2009.

41

42

Et fecerunt vitulum in Choreb et adoraverunt sculptile (Ps. 105:19).

Glyptos and sculptilis appear again in the same context, Ps. 105 (106):36.

43 Nelson and Collins 2006: 147, no. 10; Carr 2007 with emphasis on the Eucharistic symbolism.

44

45

46

PG 99: 436B.

PG 99: 436B.