CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

CELESTIAL HIERARCHIES AND EARTHLY HIERARCHIES IN THE ART OF THE BYZANTINE CHURCH

Warren T. Woodfin

In my opinion a hierarchy is a sacred order, a state of understanding and an activity approximating as closely as possible to the divine. And it is uplifted to the imitation of God in proportion to the enlightenments divinely given to it. The beauty of God – so simple, so good, so much the source of perfection – is completely uncontaminated by dissimilarity. It reaches out to grant every being, according to merit, a share of light and then through a divine sacrament, in harmony and peace, it bestows on each of those being perfected its own form.1

INTRODUCTION

The idea that earthly things are reflections of heavenly realities was part of the package of Neoplatonic ideas that Byzantium inherited from late antiquity. The idea of the resemblance between earthly and heavenly realms was intensified and given specific content by the biblical tradition and its interpretation by the Greek Fathers. To give a somewhat idiosyncratic example, the sixth-century Christian Topography that has traditionally gone under the name of Cosmas Indicopleustes2 seeks to explain the visible universe in terms of a heavenly prototype. The author rejects the old Ptolemaic notion of the universe as a series of concentric spheres. Instead, he bases his model of heaven and earth on the Tabernacle, the plans for which were revealed to Moses on Mt Sinai, for this is the divinely revealed model of the entire world  .3 The inhabited world is described as flat and rectangular, something proved to the author of the Christian Topography not only by his own travels, but by the dimensions of the Table of the Shewbread, which is twice as long as it is wide, and surrounded by a border of a palm’s breadth, corresponding to the narrow margin of earth surrounding the ocean. Just as the curtain divides the tabernacle between the outer sanctuary and the Holy of Holies, so the firmament divides the world and the visible heavens from the Kingdom of Heaven that is above the firmament. Although the specific application of such thinking in the Christian Topography is far from typical4 – most educated Byzantines continued to believe in antipodes – the idea that the visible world and its institutions reflected the realities of the invisible, heavenly sphere, was both widespread and long-lived in Byzantium.5 This mirroring of earth and heaven was present equally in the intellectual world both of the Church and of the court, but its visual expression emerged most prominently through a dialogue between the two. It is thanks to the encounter with imperial expressions of this ideology, both ceremonial and visual, that the Byzantine Church arrived at a uniquely forceful artistic statement of its own continuity with the heavenly hierarchy.

.3 The inhabited world is described as flat and rectangular, something proved to the author of the Christian Topography not only by his own travels, but by the dimensions of the Table of the Shewbread, which is twice as long as it is wide, and surrounded by a border of a palm’s breadth, corresponding to the narrow margin of earth surrounding the ocean. Just as the curtain divides the tabernacle between the outer sanctuary and the Holy of Holies, so the firmament divides the world and the visible heavens from the Kingdom of Heaven that is above the firmament. Although the specific application of such thinking in the Christian Topography is far from typical4 – most educated Byzantines continued to believe in antipodes – the idea that the visible world and its institutions reflected the realities of the invisible, heavenly sphere, was both widespread and long-lived in Byzantium.5 This mirroring of earth and heaven was present equally in the intellectual world both of the Church and of the court, but its visual expression emerged most prominently through a dialogue between the two. It is thanks to the encounter with imperial expressions of this ideology, both ceremonial and visual, that the Byzantine Church arrived at a uniquely forceful artistic statement of its own continuity with the heavenly hierarchy.

THE IMPERIAL REALM AS IMAGE OF HEAVEN

Despite Pseudo-Dionysios’ early articulation of the ecclesiastical hierarchy as a reflection of the heavenly one, in the middle Byzantine period such parallels between earth and heaven were developed most clearly in the art and rhetoric of the imperial court.6 Panegyrics recited at imperial audiences make the comparison between the heavenly court and its earthly counterpart explicit. Paul Magdalino has likened official encomia to the images impressed on Byzantine coins, which show the emperor on the obverse and Christ on the reverse side. By insisting on the mimetic relationship between the ruler and Christ, such oratory depicts the emperor as the legitimate representative of the divine power.7 In his oration at the accession of Manuel I, Michael Italikos puns on the emperor’s name and its resemblance to the name Emmanuel:

You dwell here below as a living and moving statue of the King above who made you king, Oemperor … If God is expressed in both names, he is the first and heavenly God, while you are the second and earthly one.8

This topos of the emperor’s God-like status on earth, although given a special flavor by the opportunities to play on his name, is by no means confined to Manuel’s reign. Nor was the resemblance between heaven and earth confined solely to the person of the emperor. In an elaborate series of metaphors, the eleventh-century author John Mauropous compares being introduced into the emperor’s presence to Moses’ glimpse of God on Sinai, and the path to the emperor’s throne, guarded by courtiers, to the way into Eden, blocked by the cherubim with flaming sword.9

Although we are much poorer in textual sources that treat imperial ceremonial directly, in these also we see an emphasis on the mimetic aspect of court ritual. In De cerimoniis we are faced with the rather startling fact that the loros, the imperial scarf decked with gems and pearls and the imperial symbol par excellence in the visual arts, was in fact also worn by courtiers on certain occasions such as the imperial Easter banquet.10 Its shared use at court serves a mimetic function, symbolizing the burial clothes of Christ and his glorious resurrection:

We deem the magistrates’ and patricians’ wearing of loroi on the festal day of the resurrection of Christ our God to be a type of his burial, while their being gilded is for the brilliance of this day, beaming sunlight as from the sun of Christ himself when he rose. And they, both the magistrates and the patricians, we deem to act as types of the apostles, and the worthy emperor to correspond, inasmuch as it is possible, to God.11

The text goes on to describe the other insignia of the emperor, the silk handkerchief full of earth, called anexekakia, and the buskins on his feet, as representing respectively the teaching of Christ to his disciples and his death and resurrection. However arbitrary the symbolic links may seem to us, in De cerimoniis the imperial garments are assigned specific aspects of the emperor’s role as the image of Christ.

Ceremonial dress also structures the parallels between the earthly and heavenly courts in the visual arts. Depictions of costume differ from actual ceremonial and panegyrics in one critical respect: whereas written sources, whether ceremonial manuals or encomia, tend to stress the analogy between the emperor and God, imperial art tends to avoid such direct comparisons. The emperor and Christ may be functionally equivalent, but art always maintains a distinction between them in formal terms. One may compare this reticence with the boldness of the Byzantinizing mosaic portrait of Roger II crowned by Christ in the Martorana in Palermo, where Christ’s lineaments are assimilated to Roger’s own features. William Tronzo has contrasted this “self-sufficient” Christomimesis, observable within a single image, with the more indirect approach favored in Byzantium proper.12 In the imperial art of Constantinople, the presentation of Christ’s image and the imperial image may approach asymptotically, but they never precisely coincide. To take a particularly close brush between the two as an example: the twin leaves of a tenth-century ivory diptych, now divided between Dumbarton Oaks in Washington, DC and the Gotha Schlossmuseum, bear crosses in relief, each centering a roundel (Figures 23.1a and 23.1b).13 On one side appears the bust of the emperor, on the other, that of Christ. In terms of pose, only the slight turn in the emperor’s gesture – a mark of deference – indicates that he is not fully co-equal with Christ, who is perfectly frontal in his pose.

We see a similar juxtaposition of the emperor and Christ on opposite faces of another ivory object connected to court ceremonial. Long known to scholarship as the Scepter of Leo VI, it has recently been identified as a ceremonial comb.14 The ivory shows the emperor in the company of an archangel and the Virgin Mary, who adds a pearl to his crown.15 On the reverse side, Christ appears flanked by SS Peter and Paul. The scalloped arches that frame the heads of the figures recall the semi-domes that radiate from the central space of Hagia Sophia or perhaps even the apsidal reception rooms of the Great Palace.16 One could interpret the space represented as the actual interior of Hagia Sophia, into which the heavenly figures have descended to appear in the company of the emperor, or one could view the space as an evocation of the heavenly architecture (built, of course, on the Byzantine model) into which the emperor has ascended to join the company of Christ and the saints.17 The ambiguity is doubtless deliberate, for it allows the viewer to read the image two ways, both equally flattering to the imperial dignity.

In both the diptych and the comb, Christ and the emperor are juxtaposed in similar settings on opposite sides of the same ivory. Yet, in both objects, there are more subtle tactics of visual triangulation between earthly and heavenly realms accomplished by means of dress. On the ivory comb in Berlin, the Archangel Gabriel and the emperor wear identical costumes, notably the imperial loros. The ceremonial dress of the emperor, shared with the archangels in art, expresses the ruler’s ambiguous hierarchical position between heaven and earth – first in rank on earth, but a servant of Christ in heaven.18 Similarly, the emperor on the ivory diptych leaf in Washington wears the loros; Christ on the corresponding leaf in Gotha appears, as

Figure 23.1 Ivory diptych with images of a Byzantine emperor, left (a), and Christ within jeweled crosses (b). Tenth century. Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, DC and Schlossmuseum, Gotha, Germany. (a) Dumbarton Oaks, Byzantine Collection, Washington, DC; (b) Gotha, Schlossmuseum.

usual, in antique dress. Whereas the panegyrists of Manuel I’s court could pun daringly on the likeness of his name to Christ’s own, imperial art avoided too literal a resemblance, thanks to the retention of the ancient costume of tunic and mantle for Christ. As no one would have worn such clothing in medieval Byzantium, Christ’s dress renders him semantically neutral, outside the sartorial hierarchies of the court and the Church.19 Thus imperial art expresses more obliquely than court panegyric the emperor’s quasi-divine status on earth.

If explicit imperial Christomimesis was avoided in the visual arts, the emperor’s resemblance to the archangels was embraced and elaborated.20 Not only do the emperor and the archangels share the costume of the loros, they frequently appear in one another’s company. In one of the frontispiece miniatures of the Paris Homilies of St John Chrysostom, for example, the emperor appears flanked by St John Chrysostom and the Archangel Michael.21 Although the imperial figure is labeled as Nikephoros III Botaneiates, Ioannis Spatharakis has argued that the image originally represented Michael VII Doukas – and the presence of his angelic namesake would be a logical form of flattery.22 In the miniature, the archangel actually acts in the role of a courtier vis-à-vis the emperor, presenting to him the prostrate scribe (the tiny figure next to the imperial footstool) just as a court eunuch would have presented suppliants to the emperor. The emperor is thus, according to his central position in the miniature and his placement on an elaborate footstool, accorded a superior position to that of the flanking saint and angel, who turn in toward him as in a Deesis.23 The miniatures of the Paris Homilies are not alone in placing the emperor a little higher than the angels. By the mid-fourteenth century, the headgear of certain high-ranking courtiers showed an image of the emperor on the front, flanked by an angel on each side.24 On occasion, coins and other images of the emperor even portrayed him winged like an archangel – a natural extension of the idea that he stood among them as a messenger and intermediary between God and mankind.25

The idea of the emperor’s elevation above the visible world was also conveyed in ceremonial, such as the public audience known as the prokypsis. On such occasions, securely documented in the fourteenth century but possibly practiced earlier, the emperor and his courtiers would assemble on a special platform following the liturgy on great feast-days. The emperor and his attendants would be hidden from public view by curtains while the entourage assembled. Twelve banners – with representations of archangels, holy bishops, warrior saints, and the emperor on horseback – would be carried into position flanking the tribune. These were arranged in pairs, six of each image to a side. When all was ready, the protovestiarios would give a signal for the curtains to be lowered, and the emperor would appear in full regalia, flanked by insignia held by his courtiers: a great lighted candle and a sword. The curtains were only dropped as far as the emperor’s knees, so that he would appear to levitate on the dais, and the flanking courtiers remained unseen except for their hands holding his insignia. The assembled crowds shouted acclamations, and the curtains were raised again, the banners departed, and everyone moved on to the palace for a state banquet.26 The ceremonial appearance on the tribune seems designed to treat the emperor’s person like a vision appearing from on high, and his being cut off at the knees recalls the Byzantine habit of portraying Christ at bust length to emphasize his divinity.27 The twelve banners with images of saints and angels that flank the emperor in pairs further recall the composition known as the Great Deesis, in which Christ is flanked by pairs of saints grouped according to class.28 The ceremonial appearance of the emperor thus models the heavenly hierarchy as pictured in the art of the Church.

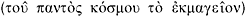

With this model in mind, we can return to one of the most famous images of the imperial majesty, the frontispiece portrait of Michael VII Doukas, altered to represent Nikephoros III Botaneiates after the latter’s usurpation in 1078, enthroned amid courtiers in the frontispiece to the Paris Homilies of St John Chrysostom (Figure 23.2).29 The emperor appears seated on a lyre-backed throne, pictured twice as large as the figures who accompany him. From either side of the back of his throne appear the personified virtues of Truth and Justice, while four courtiers flank his footstool. They appear ranged to the emperor’s left and right in accordance with

Figure 23.2 Courtiers and personified virtues surround the throne of Michael VII Doukas (r. 1071–8), altered to represent the usurper Nikephoros III Botaneiates (r. 1078–81), Paris, BnF, ms. Coislin 79, fol. 2. Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

their respective offices, given in minute inscriptions above their heads: protosproedros kai protovestiarios, proedros kai epi tou kanikleiou, proedros kai dekanos and proedros kai megas primikerios.30 The image is a locus classicus in discussions of imperial art precisely because it is so rare: few preserved images show emperors accompanied by actual courtiers, and no other work presents the court in such iconic fashion.31 As Annemarie Weyl Carr has pointed out, in the vast majority of depictions the emperor is accompanied by saints or archangels, who substitute for the earthly servants of the court.32 The epigram accompanying the frontispiece image compares the emperor to the sun as bringer of light, and, as Henry Maguire has noted, the courtiers turn inward toward him like heliotropes following the sun.33 We can compare the composition to the expanded Deesis mosaic partially preserved in the patriarchal rooms of Hagia Sophia, and dated to the late ninth century.34 There we see Christ seated on a lyre-backed throne, flanked by the Virgin and, one presumes, John the Baptist (the figure is almost entirely lost). The ranks of the Deesis are filled out with apostles, sainted bishops and SS Constantine and Helena. We may consider the leaf from the Paris Chrysostom manuscript as a Deesis with the emperor and courtiers substituting for Christ and the heavenly hierarchy, a specifically imperial modification of an ecclesiastical composition. One can compare the manuscript leaf with another commission of Michael VII, the enamels of the Holy Crown of Hungary, which show a conventional Deesis on the front of the crown and an “imperial Deesis,” including King Géza of Hungary in subordinate position, on the back.35 While the crown preserves a place of honor for Christ – he alone is shown enthroned – the parallel positions of the enamels on each side imply a similar role for the emperor. The frontispiece image in the Paris manuscript goes a step further, taking the model of Christ in the midst of the celestial hierarchy as a model for an exceptional image of the imperial glory.

The imperial court, for its part, furnished a model for envisioning the heavenly realm. We have a tenth-century description of Paradise via a near-death experience, narrating the vision of Kosmas the Monk. Kosmas, a monk in Asia Minor, after suffering from a long illness, falls asleep on 3 June 963 and experiences a vision of Paradise.36 In his vision, Kosmas travels through a paradisiacal landscape with a luxuriant garden and olive grove. Beyond these, he encounters a city girded with twelve walls of precious stone and protected by gates of gold and silver. These walls clearly echo the twelvefold foundations, also crafted from a variety of gemstones, that underpin the heavenly city in Revelation.37 Within the walls Kosmas finds streets of gold and golden houses with golden furnishings, but he encounters no mortal inhabitants until he reaches the upper part of the city, where he enters a palace with a marvelous reception hall. This, in contrast to the empty city without, is filled with people: a host of banqueters being waited on by shining eunuchs. The space of the hall, we are told, communicates via a spiral staircase with an equally sumptuous balcony. The text spells out the architectural features of the palace in sufficient detail for us to identify its earthly prototype, the Palace of the Kathisma, that is, the portion of the Great Palace adjoining the hippodrome in Constantinople and the site of imperial banquets and receptions.38 The angelic eunuchs that wait tables in Kosmas’ vision are, of course, heavenly versions of the very real eunuchs who served the equally real banquets in the court of the emperor in Constantinople.

Just as petitioners would approach the emperor at court via the mediation of courtiers, who spoke on one’s behalf, so petitions were presented to Christ through the intercession of the Mother of God and saints. The parallelism with court ceremonial is given visual form in a number of images that show the patron or donor introduced to Christ by the Virgin and saints. In each case, the saint holds the donor by the wrist, echoing the gesture of courtiers who would hold the petitioner at court by the arm.39 In a thirteenth-century Gospel book at Mt Athos, the donor, holding the book like an official gift, is introduced by the Virgin to Christ. The Virgin acts as logothetes, holding the donor’s petition, for the remission of his sins. On the leaf opposite, St John Chrysostom, standing next to the enthroned Christ, takes the role of notarios, recording on a scroll Christ’s formal response granting to the donor long life and the pardon of his sins.40 The intimate drama of personal salvation is thus given a visual form lifted from the official ceremonial of the Byzantine court. One could multiply the examples, but it is clear that images of the imperial court and the image of the celestial hierarchy drew repeatedly one on the other in ways that reinforced the notion of the court as the image of heaven, and vice versa.

REFLECTIONS OF HEAVEN IN THE CHURCH

The analogy of heavenly and ecclesiastical offices was already established very early in the patristic period and continued to exist alongside the idea of the earthly court as the mirror of the celestial hierarchy. Ignatius of Antioch, writing around the year 100, could already refer to the bishop in the assembly of his priests as the equivalent of Christ in the company of the apostles, long before such a role was applied to the emperor and courtiers by Constantine VII.41 The paired works of Pseudo-Dionysios, The Celestial Hierarchies and The Ecclesiastical Hierarchies illustrate the ideological possibilities of pairing the earthly order with a heavenly counterpart. There are a few traces from the early Byzantine period of the impact of such thinking on the visual arts. We can see its impress most clearly in a handful of works from the Kaper Koraon treasure, a hoard of liturgical silver of the sixth and seventh centuries from northern Syria.42 Two vessels from this treasure, the Riha and Stuma patens, show Christ distributing communion to the apostles, not as a participant in the Last Supper, but as officiant at a liturgy.43 Both patens, dated by stamps to late in the reign of Justin II (565–78), show Christ standing at an altar covered with a cloth and holding the Eucharistic vessels. The scene is set within the sanctuary of a church, defined on one paten by the domed canopy of the altar, on the other by a chancel screen. The images thus blur the line between the historical institution of the Eucharist and its continuous, mystical unfolding as the feast at which the ascended Christ presides.44 The intrusion of heavenly realities into earthly liturgies is emphasized also by the engraved decoration of silver liturgical fans (rhipidia) from the same treasure. These had a practical function, to keep flies from alighting on the Eucharistic elements, but quite early their decoration emphasized a symbolic interpretation. The Riha and Stuma fans bear engraved images of cherubim with four faces – human, leonine, bovine and aquiline – derived ultimately from the throne-chariot vision of Ezekiel.45 The images on the fans emphasize first of all the connection between the Christian altar and the Mercy Seat on the Ark of the Covenant, the latter overshadowed by image of the cherubim.46 Furthermore, they link the office of deacons – among whose functions it was to wield these fans at the altar – to the ministry of the angels.47 The connection was already established in patristic sources: the deacons’ liturgical function was to act as intermediaries or messengers (angeloi) between the people in the nave and the priests in the sanctuary. Various texts further connect the deacons and the liturgical gestures made with their stoles to the waving of the wings of the angels around the throne of God.48 The decoration of the fans waved by the deacons further assimilates their ministry to that of the angels.

These sorts of works of art, which freely draw associations between earthly and heavenly realities, fit awkwardly into the apologetic discourse for the veneration of icons. After all, the iconophile definition (horos) achieved at the Second Council of Nicaea (787) stipulated that the icon’s validity is based in the reality of the prototype and the artist’s more-or-less faithful rendition of that reality in an image.49 While we may attribute to Iconoclasm the scarcity of surviving works of art of this type from the early Byzantine period, the further development of this iconography after Iconoclasm was, ironically, suppressed by the very arguments used to maintain the orthodoxy of icon veneration. It is thus only after the crisis of Iconoclasm had receded into historical memory, in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, that we see works of art once again beginning to draw explicit parallels between the earthly church and the heavenly realm. The development of iconographic themes linking the realms of the Church and of heaven in a tight parallelism is one of the key innovations of later Byzantine art.

At least one impetus for this development was the visual and rhetorical connection that we have already examined, linking the imperial court and the heavenly kingdom. The sartorial influence of the imperial court on the ecclesiastical hierarchy was also critical in giving visual form to the parallels between the heavenly realm and the Church. Prior to the eleventh century, the system of liturgical vesture in the Byzantine Church distinguished only the order of the wearer, whether he was a bishop, priest or deacon. This meant that, when vested for the celebration of the liturgy, the patriarch of Constantinople would appear in exactly the same garments as the bishop of a minor provincial diocese. Over the course of the eleventh and twelfth centuries, however, new insignia were introduced at the highest levels of the hierarchy that helped to distinguish prelates not only by order, but by the rank of their see. The transformation is dramatically illustrated in two superimposed layers of fresco at the church of the Holy Anargyroi at Kastoria (Figure 23.3). St Basil is shown in the tenth-century fresco wearing plain vestments, the only ornament being the dark crosses on the broad stole (omophorion) that is the sign of his episcopal office. When the image was renewed in the twelfth century, the vestments were brought into line with what, by then, would be fitting for the dignity of Basil’s rank as metropolitan of Caesarea. The later fresco shows his outer garment, the phelonion, covered with crosses (hence called the polystaurion), a privilege restricted to the four Orthodox patriarchs and the metropolitans of Caesarea, Ephesus, Thessalonika and Corinth by the first author to mention the polystaurion, John Zonaras.50 Eventually the polystaurion was itself supplanted as the vestment of highest rank by the sakkos, a garment that seems to be modeled on the ceremonial tunic (sakkos) of the emperor himself.51 St Basil’s later image also shows him wearing gold-embroidered insignia, the epimanikia and epigonation, also introduced in this period as the special regalia of bishops and archbishops. These new insignia eventually filtered down to lower ranks of clerics, as is illustrated by the history of the

Figure 23.3 St Basil in the simple vestments of the tenth century (above) and the more elaborate episcopal insignia of the twelfth century (below). Superimposed frescoes in the church of the Holy Anargyroi, Kastoria, Greece. Velissarios Voutsas.

epimanikia, or liturgical cuffs. In the first written notice of the cuffs, an eleventhcentury letter of Patriarch Peter of Alexandria to Michael Keroularios, they appear as specifically patriarchal insignia. The canonist Theodore Balsamon, writing in the late twelfth century, describes the epimanikia as restricted to bishops; finally, in a thirteenth-century diataxis, or book of liturgical rubrics, they are mentioned as worn by priests as well.52 The spread of originally exclusive insignia to lower ranks of clergy in turn spurred the creation of still more distinguishing vestments for the highest prelates. The effect of these additions to the repertoire of liturgical vestments was to introduce visible distinctions into the hierarchy of ecclesiastics comparable, in some respects, to the established distinctions among the ranks of courtiers surrounding the emperor. It also allowed for a more complex series of visual cross-references between the earthly Church and the heavenly realm than had previously been possible.

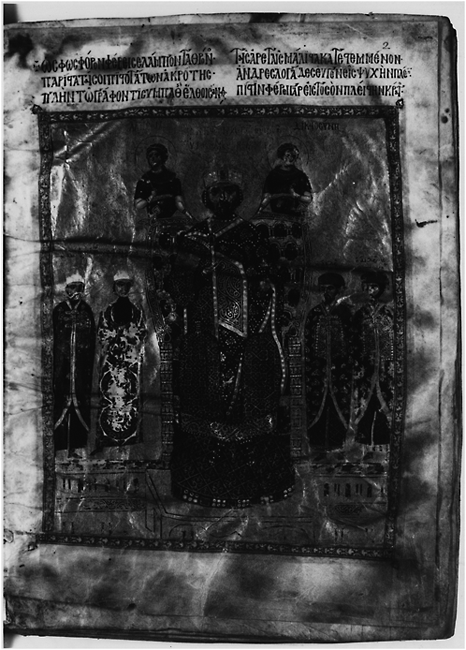

A key to this series of cross-references was the introduction, toward the end of the twelfth century, of embroidered figural imagery on liturgical vestments. While the earliest Greek theology asserted that the bishop or priest ministered in persona Christi, it was only at this point that the vestments of the clergy began to make this function of representing Christ concrete through embroideries of his image and scenes from his life. By wearing Christ’s image, both in the form of his iconic portrait and as the pictorial synopsis of the Gospels, the clergy assumed the role not just of representatives of Christ, but literally representations of him. Thanks to the widespread popularity of mystagogical interpretations of the liturgy that mapped each action of the celebrant onto an event from the Gospels,53 the sequence of narrative images covering a vestment such as the Major Sakkos of Photios, dating between 1414 and 1417, expressed the wearer’s role as the living symbol of Christ (Figure 23.4).54

This development was complemented by contemporaneous developments in wall painting. Programs of fresco painting increasingly embraced subject matter that blurred the line between heavenly and earthly liturgies.55 From the fourteenth century, depictions of the Communion of the Apostles begin to depict Christ standing at the altar, not in antique dress, but in the distinctive vestments of a Byzantine patriarch. The earliest examples are found at St Nicholas Orphanos in Thessalonika and at St Nikita in  u

u er, both dating to the second decade of the fourteenth century.56 In both cases, Christ appears vested in the patriarchal sakkos and the omophorion, and angels dressed as deacons assist him at the altar. We have already seen the connection between angels and deacons exploited in the liturgical fans from the Kaper Koraon treasure. In post-iconoclastic art angel-deacons appear in some of the earliest representations of the Communion of the Apostles, at St Sophia in Kiev and St Sophia in Ohrid, both of the eleventh century.57 In the Palaiologan period, the hierarchy of angel-clergy was filled out with angel-priests in addition to angeldeacons. At the Peribleptos church at Mistra, the frescoes depict a Great Entrance procession enacted by angels vested both as priests and as deacons. The angel-priests carry veiled chalices, while the angel-deacons balance veiled patens on their heads as they process toward an altar where Christ himself presides.58 The postures, peculiar as they may seem to modern eyes, are precisely those stipulated in late Byzantine diataxeis, or books of liturgical directions.59 As with the images based on court ceremonial, the heavenly figures act according to earthly ritual norms. Here, the

er, both dating to the second decade of the fourteenth century.56 In both cases, Christ appears vested in the patriarchal sakkos and the omophorion, and angels dressed as deacons assist him at the altar. We have already seen the connection between angels and deacons exploited in the liturgical fans from the Kaper Koraon treasure. In post-iconoclastic art angel-deacons appear in some of the earliest representations of the Communion of the Apostles, at St Sophia in Kiev and St Sophia in Ohrid, both of the eleventh century.57 In the Palaiologan period, the hierarchy of angel-clergy was filled out with angel-priests in addition to angeldeacons. At the Peribleptos church at Mistra, the frescoes depict a Great Entrance procession enacted by angels vested both as priests and as deacons. The angel-priests carry veiled chalices, while the angel-deacons balance veiled patens on their heads as they process toward an altar where Christ himself presides.58 The postures, peculiar as they may seem to modern eyes, are precisely those stipulated in late Byzantine diataxeis, or books of liturgical directions.59 As with the images based on court ceremonial, the heavenly figures act according to earthly ritual norms. Here, the

Figure 23.4 Scenes from the life of Christ, figures of saints and the embroidered text of the Nicene Creed: the “Major Sakkos” of the metropolitan Photios, a Byzantine liturgical vestment of about 1414–17. Kremlin Armory, Moscow.

difference is that the heavenly figures dress exactly as do their earthly counterparts. What is more, the action of the celestial liturgy is depicted at monumental scale in the same space in which its earthly model (or, as Byzantine theologians would insist, its earthly copy) takes place.60

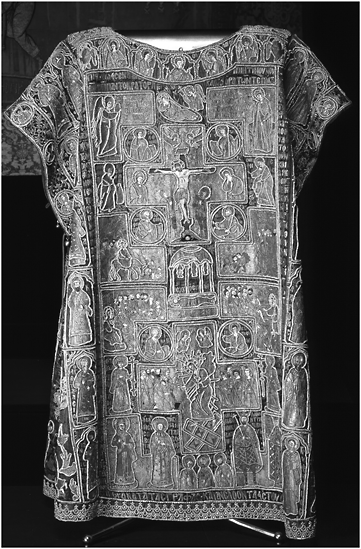

These images of Christ as bishop and angels as assisting clergy that appear in monumental painting in the final centuries of Byzantium eschew the indirect linkages of earth and heaven favored by imperial imagery to present a vision of the heavenly hierarchy as an exact mirror-image of the earthly Church. Perhaps the most striking example of the interchangeability of the heavenly and ecclesiastical hierarchies in late Byzantine art is the iconostasis curtain from Chilandar monastery on Mt Athos, embroidered in 1399 (Figure 23.5).61 On this textile, Christ appears as a patriarch in the short-sleeved vestment – the sakkos – and the distinctive crossed broad stole of a bishop, flanked by SS Basil and John Chrysostom, the reputed authors of the Byzantine liturgy. The dress and pose of the flanking saints imitate that of bishops assisting a patriarch at mass. Angels act as deacons, waving liturgical fans behind them. In contrast to painted scenes of the Communion of the Apostles, there is no altar depicted on the textile, which would have hung in the central doors of the icon screen between the nave and sanctuary. When the curtain was drawn aside at the Great Entrance and at the Communion, it would have revealed the human celebrant standing in Christ’s place at the altar table.62 The veil and its embroidered imagery stress the very thinness of the division between the heavenly hierarchy and that of the Church on earth.

AFTER THE FALL OF CONSTANTINOPLE

The system of visual correspondences between the hierarchy and ritual of the earthly Church and that of the Kingdom of Heaven was comprehensive, but it never entirely displaced the system of imperial references. The archangels continue to wear the loros in Palaiologan and post-Byzantine painting, often alongside images of angels in liturgical dress. To judge from the textual sources, Palaiologan court ceremonial became more, not less, Christomimetic than that of the middle Byzantine period. We learn from Pseudo-Kodinos, for instance, that the emperor washed the feet of twelve of the poor on Holy Thursday, in imitation of Christ’s washing the feet of the disciples.63 In this case, though, the ritual was a borrowing from the ecclesiastical sphere, having long been the practice of bishops and monastic superiors.64 While ecclesiastical art and ceremonial continued to take cues from the imperial court and vice versa, it is clear that by the mid-fourteenth century the Byzantine Church had taken the lead in crafting visual assertions of its continuity with the heavenly sphere.

There was a fundamental difference, however, in the structures of the parallel hierarchies of the Church and of the imperial court. The imperial system was strictly pyramidal, with the emperor standing at its peak as the intermediary with the realm of divinity. Ceremonial manuals and lists of precedence carefully ensured that the unique rank of each office at court was expressed in its costume, creating an orderly chain of authority descending from the emperor. Despite the introduction of garments of rank into liturgical dress from the eleventh century on, the ecclesiastical vesture never developed such a degree of differentiation among the ranks of clergy. The ecclesiastical hierarchy claimed universal authority, but it did not vest these claims in a single office. While apologists for the privileges of the patriarchate of Constantinople could claim that the Church has “Christ as its head and the patriarch as his image,”65 their claims were counterbalanced by the equal insistence that each bishop fully represents Christ in the liturgy.66

Despite this internal tension, the hierarchy articulated by vestments, painting and ceremonial of the late Byzantine Church managed to express its claims to reflect heavenly realities with greater immediacy than ever possible in the imperial sphere. Whereas the emperor and archangels could pass back and forth across the permeable barrier between the court and heaven, their dress and rank changed depending on

Figure 23.5 Christ vested as a Byzantine patriarch, attended by SS Basil and John Chrysostom and by angels vested as deacons. Iconostasis curtain of 1399, Chilandar monastery, Mt Athos. Dumbarton Oaks Photo and Fieldwork Archive, used by permission of the heirs of Ivan Ðjor jevi

jevi .

.

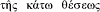

which realm they occupied.67 The ecclesiastical hierarchy, on the other hand, was able to present itself as a direct mirror of the heavenly one. Distinctions between the two collapsed further as the empire drew toward its own dissolution. There survives a sizeable group of Ottoman textiles from the fifteenth through seventeenth centuries that show, in repeated roundels, the image of Christ as High Priest, clad in patriarchal vestments and blessing with both hands (Figure 23.6).68 Such fabrics may have already been imported into Constantinople before 1453, as we know to have been the case for Italian textiles.69 Their decoration echoes that seen on the sakkoi worn by Christ in Palaiologan painting, with all-over patterns of crosses and circles. Whereas the earlier, embroidered liturgical vestments create links between the celebrant and Christ by triangulating between the vested clergy, liturgical mystagogy and representations in wall painting, these vestments collapse such distinctions. Neither outside visual cues nor prior knowledge of liturgical mystagogy is necessary to read

Figure 23.6 Christ vested as a Byzantine patriarch. Ottoman woven silk and metallic-thread twill, sixteenth or seventeenth century. Dumbarton Oaks Byzantine Collection.

such images: they make visible in the plainest possible terms the hidden identity of the clergy with Christ their head.

NOTES

1 Pseudo-Dionysios, Celestial Hierarchies, III.1, PG 3: 164D; trans. Luibheid 1987: 153-4.

2 The name Cosmas Indicopleustes first appears in catenae of the eleventh century; an attribution of the Christian Topography to Constantine of Antioch has been suggested: Wolska-Conus 1989: 2830.

3 Christian Topography V.20, ed. Wolska-Conus 1968-73, II: 39; cf. Exodus 25:40; Hebrews 8:5, 9:1-12, 23-4.

4 On relevance of the Christian Topography to the debate over images, see Brubaker 2006.

5 On this topos, see Mango 1980: 151-3.

6 The following discussion is based on the fundamental observations of Maguire 1997a.

7 Magdalino 1993: 415.

8 Magdalino 1993: 437.

9 de Lagarde and Bollig 1882: 28-31.

10 On the loros in imperial images and texts see Parani 2003: 18-24; and Maguire in this volume.

11 De cerimoniis II.40, ed. Reiske 1829-30: 637-8. My translation.

12 Tronzo 1997: 107-9.

13 Anthony Cutler dates the pair of leaves to the sole reign of Constantine VII (945-59): Cutler 1994: 220-1.

14 Cutler 1994: 200-1; Maguire in Evans and Wixom 1997: 201-2; Bühl and Jehle 2002: 289-306.

15 Arnulf 1990: 82-3.

16 Corrigan 1978: 413; Arnulf 1990: 82; and Featherstone in this volume.

17 Maguire 1997b: 249-50.

18 Maguire 1997b: 249.

19 For similar observations on the non-imperial character of Christ’s costume in early Christian art: Mathews 1993: 101, 178-9.

20 Maguire 1997b: 247-51.

21 Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, ms. Coislin 79, fol. 2v.

22 Spatharakis 1976: 111-12.

23 Dumitrescu 1987: 40-2; Maguire 1997b: 249. Spatharakis echoes Bordier’s identification of the prostrate figure as the painter, although the mention of the scribe in the inscription at the top of the leaf makes him the more logical identification. Spatharakis 1976: 112.

24 Verpeaux 1966: 152.

25 Maguire 1997b: 252-5.

26 Verpeaux 1966: 195-204.

27 Oration 34 of Leo VI is explicit in describing the half-length image (

) of Christ in the dome of the church of Stylianus Zaoutzas, interpreting it as a symbol of Christ’s sublimity. Akakios 1868: 275.

) of Christ in the dome of the church of Stylianus Zaoutzas, interpreting it as a symbol of Christ’s sublimity. Akakios 1868: 275.

28 On the iconography of the deesis: Walter 1980; Cutler 1987.

29 On the Byzantine alterations to the images and their inscriptions, as well as the modern alterations to the foliation: Spatharakis 1976: 107-15.

30 Spatharakis 1976: 110.

31 But compare the lost image of Manuel I Komnenos in the midst of the virtues: Magdalino and Nelson 1982: 142-6.

32 Carr 1997: 84-5.

33 Maguire in Evans and Wixom 1997: 209.

34 Cormack and Hawkins 1977: 212-31, 235-44, pls 26-47; Grabar 1984: 193-4.

35 Maguire 1997b: 247-8; Maguire 1997c: 188; Wessel 1967: 111-15.

36 Angelidi 1983b.

37 See Revelation 21:15-21.

38 Müller-Wiener 1977: 229, 236. See also Featherstone in this volume.

39 Šev enko 1994: 273-5.

enko 1994: 273-5.

40 Šev enko 1994: 274–5; Belting 1970: 35–7, 72.

enko 1994: 274–5; Belting 1970: 35–7, 72.

41 Ignatius, Letter to the Smyrnaeans, VIII.1, ed. Camelot 1958: 162.

42 M. Mango 1986: 6–8, 20–34.

43 M. Mango 1986: 165–70, 171–2.

44 M. Mango 1986: 159, 165; Schulz 1986: 103–4. Compare the depiction of the Communion of the Apostles in the late sixth-century Rossano Gospels, fols 3v–4r. Cavallo 1992: 24, pls 6–7.

45 M. Mango 1986: no. 32, 150–4. Cf. Ezekiel 1:4–21. On the iconography of cherubim and seraphim: van der Meer 1938: 255–9; Peers 2001: 46–9.

46 Exodus 25:17–22, 37:7–9; cf. Hebrews 9:5.

47 Apostolic Constitutions VIII.12.3–4, cited in M. Mango 1986: 151.

48 Pseudo-Chrysostom, In parabolam de filio prodigo, PG 59: 520; Germanos, Historia ecclesiastica, PG 98: 393C; Pseudo-Sophronios, Commentarius liturgicus, PG 87: 3988D; Philotheos, Ordo sacri ministerii, PG 154: 753A, 756B–D; Trempelas 1912: 6, 83.

49 Tanner 1990: 133–8.

50 Papas 1965: 755; Ralles and Potles 1852–9: II, 260. The slightly later canonist Theodore Balsamon attempts to restrict the polystaurion to patriarchs exclusively. Braun 1907: 237; Papas 1965: 755; Theodore Balsamon, Responsa ad Marcum, PG 138: 989A; idem, Meditata, PG 138: 1020C, 1025D, 1028B.

51 Papas 1965: 125. On the imperial sakkos, see Parani 2003: 23–4; Hendy 1999: 157.

52 Michael Keroularios, Epistolae, PG 120: 800C; Theodore Balsamon, Responsa ad interrogationes Marci, PG 138: 988D; Trempelas 1912: 1a. On the privileged use of the epigonation by priests of rank, see Symeon of Thessalonika, De sacra liturgia, PG 155: 261D–264A.

53 Schulz 1986; Bornert 1966.

54 Mayasova 1991: 44–50.

55 On the theme of the celestial liturgy: Walter 1982: 217–21.

56 Walter 1982: 216.

57 Lazarev 1960: pls 33, 34; Hamann-MacLean and Hallensleben 1963: II, 224–5, pl. VI.

58 Dufrenne 1970: 14, fig. 62.

59 Taft 1975: 206–7; Trempelas 1912: 9.

60 See Symeon of Thessalonika, Contra haereses, PG 155: 340.

61 Millet 1939–47: 76–8, pl. CLIX.

62 On the curtain in the sanctuary entrance: Taft 1975: 411–16.

63 Verpeaux 1966: 228–9.

64 Tronzo 1994: 61–2.

65 Nikopoulos 1981–2: 461.

66 Symeon of Thessalonika, Expositio de divino templo, PG 155: 709A.

67 Maguire 1997b: 256–7.

68 Atasoy et al. 2001: 176–81, 241, 244.

69 Lowry 2003: 40–2, 63–4.