CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

CONSTANTINOPLE AND THE CONSTRUCTION OF A MEDIEVAL URBAN IDENTITY

Robert Ousterhout

INTRODUCTION

In his novel, Plowing the Dark, published in 2000, the writer Richard Powers summons the image of Justinian’s great church, Hagia Sophia, to represent the fabled city of Constantinople and its cultural legacy, inspired by Yeats’ poem, “Sailing to Byzantium.”1 In doing so, he adheres to a long-established literary tradition. Following the example of classical rhetoric, Byzantine writers often included descriptions of well-known buildings in their texts.2 Focusing on significant details, the ekphrasis of a monument was meant to evoke a visual image in the mind of the reader; more importantly, it could symbolize an abstract idea to reinforce the main theme of the text. Properly read, the literary evocation of a monument could represent imperial authority, piety or even urban identity. It is not surprising that the ekphrasis was a favorite literary motif of the writers of Byzantine Constantinople, a city filled with a rich repertory of historical monuments, with which their readers would have been familiar. Nor is it surprising that these evocative architectural descriptions have inspired a wealth of imaginative secondary literature, Yeats’ poem included.

Similarly, the view of Constantinople in current scholarship has been based on texts; the city is today more the realm of the philologist rather than of the archaeologist. We have learned much about the city from scholars such as Cyril Mango, Gilbert Dagron, Paul Magdalino and others, but their important studies construct Constantinople as a city of words, and their books appear almost entirely without illustrations.3 Unlike other ancient capitals, modern Istanbul has witnessed virtually no urban archaeology, and basic elements of the Byzantine city, such as the street system, public spaces and housing, remain all but unknown.4 When new evidence enters the picture, it usually raises more questions than it answers. As a case in point, the much discussed salvage excavation at the Theodosian Harbor, ongoing since 2005, emphasizes how much we do not know about the history of the city.5 Both the initial construction and the longevity of the harbor must now be reconsidered.6 The picture is similar as we move away from the harbor. In spite of the hundreds of surviving texts that address Constantinople, its monuments and its institutions, the city is perhaps most remarkable for what we do not know about it (Map 4). We know in general terms the locations of the main street, the Mese, and the fora that it traversed. But even the sizes of the fora elude us: although we have fixed monuments in both, the boundaries of the Fora of Constantine and Theodosius have never been securely determined.7 And we lack the details that a more thorough archaeological examination might provide. For example, what kind of urban dwellings were there?8 Was the city laid out on a grid system?9 It is difficult to write an urban history without this sort of information.

THE INVENTION OF CONSTANTINOPLE

From the perspective of urban history, Constantinople is normally discussed as a late antique city, but it had a long and difficult history. In the early centuries, the novelty of the city allowed flexibility in both its planning and its symbolism, as it was established as a ritual center. Although little physical evidence survives, the symbolic meaning of the city is revealed in the texts. Lacking both a significant historical role and a Christian past, it required more than a small amount of inventiveness to situate the city symbolically as the capital of a world empire. As the architects of Constantine and his successors established an urban matrix, replete with the monuments necessary for it to function as an administrative center, they also created a visual vocabulary to assert the primacy of the city, to associate it with Rome, Troy and Jerusalem – that is, to present it as an imperial and religious center, grounded in a common mythology.

The idea of the Byzantine capital as “New Rome” or “Second Rome” is a topos that pervades the literature throughout the Byzantine period, and the degree of imitation, real or imagined, is striking.10 Mimesis guided much of the creation of meaning in the new city, a rich combination of topographical, monumental and literary comparisons. Like Rome, the city of Constantine was built on seven hills and divided into fourteen districts; its imperial palace lay next to its hippodrome, which was similarly equipped with a royal viewing box. As in Rome, there were a senate house, a Capitol, great baths and other public amenities; imperial fora provided its public spaces; triumphal columns, arches and monuments, including a colossus of the emperor as Apollo-Helios, and a variety of dedications imparted mimetic associations with the old capital.11 Even Constantine’s mausoleum was established in a position that encouraged a comparison with that of Augustus’ mausoleum in Rome.12 “New Rome” was a conceit firmly established from the beginning and developed in word and image.

But early Constantinople could also be viewed as “New Troy” – that is, the legendary ancestral home of the Romans in the East, from which Aeneas fled following its sack by the Greeks. Constantine is said to have considered establishing his new capital at Troy, and much of the borrowed symbolism in early Constantinople referred to the Trojan legend.13 The sculptural program in the main public bathing institution, the Baths of Zeuxippos, for example, centered on the Trojan legend.14 The colossal statue of Constantine once displayed atop the porphyry column in his forum is also claimed to have come from Troy; the base of the statue is said to have contained the palladium, the ancient wooden guardian statue associated with Troy and its fortunes, later with Rome and its destiny.15 As Sarah Bassett argues, early Constantinople was very much an intellectual construct, one that “grew up around the intersection of history and myth … that makes the city the last link in a chain of destiny that stretched from Troy to Rome.”16

The idea of the city as “New Jerusalem” may be a bit more elusive. In 446, the Mesopotamian monk Daniel the Stylite, on the road to visit the holy sites of Palestine, met a mysterious figure who told him in no uncertain terms not to go to Jerusalem, “but go to Byzantium, and you will see a second Jerusalem, namely Constantinople. There you will rejoice in the shrines of martyrs and imposing places of prayer.”17 Accordingly, Daniel headed north and set up his column in a suburb of the Byzantine capital. Ever since the time of Daniel, there are occasional references to Constantinople as the New Jerusalem. In fact, this happens more often in current scholarship than in Byzantine texts. Scholars love the dual epithet “New Rome and New Jerusalem,” as it seems to express the combined political and religious ambitions of the city, its unique linkage of power and status.18 However, the association with Jerusalem did not rely on urban mimesis or geographical proximity or historical resonance, but rather on the rich collections of relics that city gradually accumulated, beginning with the translation of the relics of Andrew, Timothy and Luke into the church of the Holy Apostles. More than 3,600 relics are recorded, representing at least 476 different saints, most of which were imported.19 Those collected in the Pharos chapel in the Great Palace were from the Passion of Christ and seem to relate specifically to Jerusalem, although this may represent developments of the middle Byzantine period.20 “New Jerusalem” thus became a metaphor for the increasingly sacred character of the city.21

CONSTANTINOPLE IN TRANSITION

By the sixth century, late antique Constantinople was both rich and evocative, firmly grounded both as an imperial capital and as a sacred city, situated within the broader context of world history and Roman mythology. Then things began to change. Ravaged by the plague in the sixth century, the city witnessed a severe decline and transformation in the Dark Ages of the seventh and eighth centuries. This period effectively marked its redefinition from a late antique to a medieval city. Constantinople had a population of perhaps 500,000 in the fifth century, which could have only been supported with a well-organized trading network that brought wheat from as far away as Egypt, and this also required sufficient ships, harbors and warehouses. Elaborate works of engineering, like aqueducts and cisterns, were also necessary to provide and store water for the inhabitants. Without an elaborate system of trade and without quantities of water, a city of this size could not survive, and the population declined dramatically after the seventh century. Prior to the Arab siege of 717–18, Anastasius II expelled all inhabitants who could not lay in a three-year supply of provisions. The population must have shrunk to perhaps one-tenth of its former size.22

One result of the de-urbanization of the Dark Ages and one measure of the transformation is that the great public works characteristic of a late antique city either fell into ruin or were transformed in function. For example, the Forum of Constantine, which continued to be an important landmark, became the main emporium for the city, surrounded by the quarters of artisans. Perhaps noteworthy, in the ninth century, Basil I built a church there, dedicated to the Virgin, having observed that the workers lacked both a place of spiritual refuge and somewhere to go to get out of the rain. Cyril Mango views this statement as significant in that it suggests that the church had replaced all other centers of social gathering.23 At the same time, it implies that the arcades and porticoes, which were part and parcel of the late antique city, no longer existed. Elsewhere in the city, we are told, the Forum of Theodosius became the market for livestock, and further fora were similarly transformed.

The rule of Constantine V (741–75) may mark the turning point in the city’s fortunes: the point at which Constantinople became a medieval city.24 Born during the Arab siege of 717–18, he was the son of Leo III, who had instituted the ban on images in 726. Constantine V was probably the most reviled of the iconoclast emperors, but, as Magdalino argues, his interventions allowed Constantinople to continue. He rebuilt the land walls immediately following the devastating earthquake of 740, as the numerous inscriptions testify. He also rebuilt the aqueduct system, which had been out of service for more than a century.25 Completed in 766, the scope of the work, as outlined by Theophanes, suggests this was not simply the so-called Aqueduct of Valens inside the city, but the long system of channels and bridges extending deep into Thrace. Constantine V also reorganized the urban core of the city, concentrating trade at the Harbor of Julian, and repopulated it following the plague outbreak of 746–7. He was also responsible for the reconstruction of Hagia Eirene, the second largest surviving Byzantine church in the city. Destroyed in the 740 earthquake, Hagia Eirene was rebuilt on a more stable (and influential) plan, for which dendrochronological analysis suggests a date shortly after 753.26 And while there is evidence of the removal of figural decoration from Hagia Sophia during this period, such as the Sekreton mosaics, the replacement work was clearly done by skilled mosaicists.27 Taken together, we may begin to suspect a coherent building program with ideological overtones.

Building activity in Constantinople was continued under Constantine’s iconoclast successors. Further repairs to the land walls were carried out under Leo IV and Constantine VI, Leo V and Theophilos.28 The last is best known for the construction of palaces,29 and additions to the Great Palace. Perhaps more importantly, Theophilos had the sea wall and Golden Horn wall substantially rebuilt, as the numerous surviving inscriptions testify. The number of recorded inscriptions from the Golden Horn alone, sixteen in all, suggests the revival of commercial activity in this area of the city under Theophilos.30 The claim of one inscription that Theophilos had “renewed the city” might not be far from the truth, but it is best seen as one stage in a century-long program of urban revival, beginning with Constantine V and extending into the reign of Basil I.31

The changes in the nature of patronage are significant, moving away from public monuments to private foundations: churches, monasteries, hospitals and orphanages are noted, but not new streets, fora, triumphal monuments and the like. Following the ninth century, most of the significant institutions within the city were private rather than public, and most were connected to large monasteries.32 In fact, the structure of the society, and consequently of the city, had shifted from open to closed, and its unified nature was gradually replaced with, in effect, a series of villages within the walls. Indeed, this is how the city is represented in our earliest plans, from the fifteenth century.33 Ibn Battuta, writing in 1332, said the inhabitants lived in thirteen separate villages.34

BUILDINGS IN TRANSITION

The meaning of the late antique city as analyzed above, is derived primarily from textual references, insofar as they have been deciphered in current scholarship. The rich and overlapping elements of urban iconography were critical to the selfawareness of the city’s inhabitants, as well as to its many visitors. The image of Constantinople that I would like to evoke is of a city in transition. Based on the evidence provided by its surviving monuments, it should be possible to envision the city not as something static and fixed in time, but as something dramatic and changing. Although we have little evidence for either the maintenance or the elaboration of the urban matrix, the transformation of specific monuments may be seen as reflecting the changing nature of the city as a whole. In this respect, the close analysis of surviving buildings may be informative.

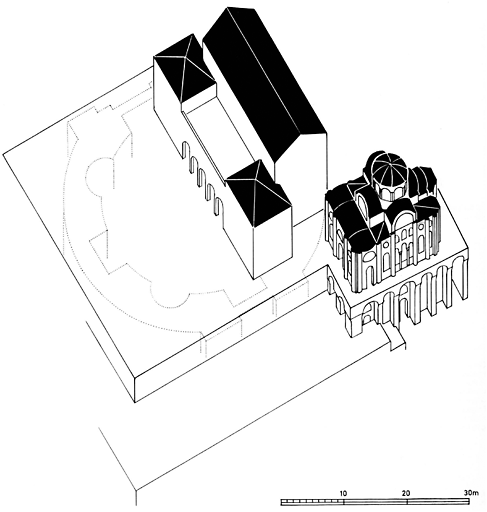

The church of Hagia Euphemia at the hippodrome is known from excavations (Figure 25.1).35 It began its life in the fifth century as the centerpiece of an aristocratic palace built by a high court official, an uppity eunuch of Persian origin named Antiochus, who served as praepositus, cubicularius, praetorian prefect, patrician and consul under Theodosius II. The palace was entered from a street perpendicular to the north side of the hippodrome, accessible by means of an elegant semicircular portico and garden. Symmetrically disposed pavilions of intricate geometry opened onto the portico. On the central axis lay a large ceremonial hall or triclinium, which was hexagonal and niched in plan, and covered by a dome. Small colonnaded porticoes opened outward to the surrounding gardens. We might imagine the palace complex to have been a smaller version of the pavilions and gardens of the Great Palace, for when Antiochus overstepped his position, he was accused of living “like an emperor, not like an emperor’s minister.”36 His palace was confiscated around 436, and he was forced to take holy orders. Sometime later – although it remains unclear exactly when – its hexagonal hall was converted into a church, dedicated to a local saint, Euphemia, whose main shrine lay in Chalkedon. In the troubled seventh century, when the Asian shore was threatened by Persian attack, the relics of Euphemia were transferred by the emperor Heraclius for safekeeping, either in 615 or 626.37 Mathews had argued for a sixth-century conversion for the building, before the transfer of relics.38 A later conversion seems more likely, perhaps even as late as the 796 restoration by Eirene and Constantine VI.39 Once Euphemia was established near the hippodrome, however, tombs and mausolea were added around the building as her cult grew in importance.40 In the late thirteenth century following the Latin occupation, the church was restored once again and redecorated with a cycle of paintings chronicling the life of Euphemia.41

Each step in the transformation of the site had important reflections in the transformation of the city around it. Antiochus’ palace lay in a position indicative of his political importance. The emphasis on ceremonial spaces reflects the ritualization of daily life among the aristocracy in late antiquity; Antiochus, as the charges against him suggest, was living like an emperor. The conversion of the palace into a place of Christian worship reflects the rising power of the Church, which gradually took over many official duties of the state administration and assumed a role in civic governance.42 Similarly, the incorporation of the saint’s relics reflects both the reduction in scale of the city during the Dark Ages and its increasingly sacred character. While

Figure 25.1 Palace of Antiochus (church of St Euphemia), site plan, redrawn after MüllerWiener 1977.

Euphemia’s original martyrium in Chalkedon seems to have disappeared from the historical record, the relocation of her sanctuary at the very center of the city accords with the functional and ideological redefinition of the city in the early Middle Ages. A restoration at the end of the eighth century would fit with the urban revival under the efforts of Constantine V and his successors.43 The addition of burials around the church marks a fundamental transformation in the character of the city. While Roman law had prohibited burials inside the pomerium of the city, during the Middle Ages intramural burials became increasingly common, often set in relationship to sacred space or sacred objects.44 Finally, the redecoration of the church in the late thirteenth century represents the attempt to reassert the city’s sanctity in the wake of the Latin occupation, when many of its holy shrines were plundered. As a defender of Orthodoxy, whose shrine lay at the heart of the city, Euphemia would have gained new resonance against the backdrop of Palaiologan attempts for a union with the Church of Rome.45

We can witness a similar history of transformation at the Kalenderhane Camii (Theotokos Kyriotissa), thanks to the careful excavation of Striker and Kuban (Figure 25.2).46 The archaeologists identify six major construction phases at the site following the construction of the Aqueduct of Valens, which forms its northern boundary. The historical development represents responses to preexisting site conditions, as older components were incorporated into new structures. The site developed from a small bath erected c. 400, into an increasingly complex agglomeration with two churches set side by side at different angles. It is unclear when the north church fell out of use; as it survives, the south church represents a major period of construction c. 1195–1204. Rapidly built and expensively furnished, it incorporated a variety of older vaulted components.47 Thanks to the odd angle at the connection to the aqueduct, we can begin to get some sense of an urban grid and the relationship of the building to it.48

The Myrelaion Palace underwent a similar transformation through its long history (Figures 22.1, 25.3).49 Here we may see that accompanying the changes in patronage there was often a change in scale. From the first phase of construction on the site, an enormous rotunda survives. This seems to have been the vestibule of a late antique urban palace. In the early tenth century, the walls of the rotunda were filled in with a colonnaded cistern to form a platform for the construction of the family palace of the emperor Romanos Lekapenos. The general plan of the palace may be reconstructed as a pi-shaped building with a central portico opening onto a courtyard. Except for the palace chapel, all components of Romanos’ palace were built on the area taken up solely by the entry vestibule of its predecessor. The chapel was built as a private family chapel; its design is elegant, and it was lavishly decorated with marble cladding, mosaics and glazed ceramics, but the dome of the Myrelaion is barely 10 feet in diameter, a dramatic contrast to the 100-foot dome of Hagia Sophia. The smaller scale should be seen not as a reflection of strained circumstances, heavy taxation or limited technology, but as indicative of the changes in the orientation of Byzantine society, from public to private.50

Shortly after it was constructed, the entire Myrelaion Palace was converted into a nunnery. This change corresponds to the rise of monasticism, which became an essential element in Byzantine society. In addition, the change tells us something about the organization of Byzantine monasticism, for it seems no major remodeling was necessary. The structure within a monastic community, it seems, was similar to that of an aristocratic household, and the architectural setting could be similar as well.51 At the upper levels of society, both consisted of a closed social group, hierarchically organized, with servants, retainers, properties and economic interests. The conversion of secular properties was a matter of concern in the middle Byzantine period, resulting in an attempt to provide a legal definition of a monastery, and to protect the small property owner from the threat of takeover.52 The Council of Constantinople of 861, for example, spoke against the founding of monasteries in private houses, although it may not have had much effect.53

The Myrelaion chapel was intended from the beginning to be the burial place of Romanos and his family.54 While it is unclear where within the chapel the tombs were situated, Romanos established a new precedent for imperial burial, replacing

Figure 25.2 Kalenderhane Camii (Theotokos Kyriotissa), reconstruction site sketch showing main phases: A. c. 400; B. late sixth century; C. after 687; D. tenth to twelfth centuries; E. c. 1195–1204, from Striker and Kuban 1997.

Figure 25.3 Myrelaion Palace (Bodrum Camii), reconstructed view, from Striker 1981.

the church of the Holy Apostles.55 As a usurper who had positioned himself as fatherin-law to the legitimate emperor, Romanos was in a sensitive position, and we may speculate that to have prepared a burial place for himself at the Apostoleion would have seemed imprudent.56 Whatever his motivation, by the early eleventh century it had become de rigueur for the emperor to found an urban monastery as a setting for burial.57

The rising importance of privileged burials within the city is seen in the late Byzantine period as well, when the substructures of the Myrelaion chapel were refurbished to house extensive aristocratic burials.58 The ad hoc nature of the burials, set within a preexisting architectural space, parallels the retrofitted burials in the narthexes of the Chora monastery, where they began to appear within a few decades of the reconstruction by Theodore Metochites, c. 1316–31.59

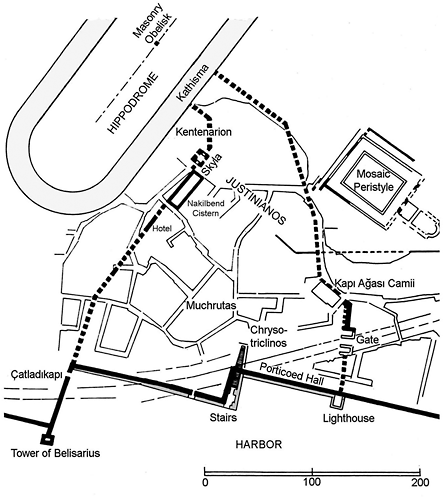

Also emphasizing the change in scale, the so-called Boukoleon Palace represents the reduced core of the Great Palace, as it was enclosed by a fortification wall by Nikephoros Phokas in the tenth century (Figure 25.4).60 This area, some distance from Hagia Sophia, comprised the ceremonial core of the palace during the medieval centuries, and did not include the famed mosaic peristyle, the Chalke Gate, the Magnaura, nor many other of the important ceremonial spaces of late antiquity. It enclosed the audience hall known as the Chrysotriklinos and the famed Pharos church, as well as the Seljuk-style pavilion known as the Muchrutas.61 The so-called Palace of Justinian may follow the model of a late antique seaside palace, but it seems to have been constructed entirely of spolia – and a very mixed batch at that.62 Cyril Mango has tracked the indications of the fortification wall: to the west, the wall extended from the so-called Belisarius tower and the Çatladıkapı, extending northward to meet the hippodrome at the Kathisma. Along its western perimeter, the wall extended northward from the lighthouse, and its like may be traced to include the

Figure 25.4 Boukoleon Palace, hypothetical plan, redrawn after Mango 1997.

remnants of a fortified gate, which faced eastward, and traces of a wall beneath the Kapı A ası Camii. Much of the eastern wall is uncertain, but a salvage excavation carried on Küçük Ayasofya Bulvarı turned up a portion of the defensive wall, which now decorates the lobby of the Eresin Crown Hotel.63 The fortification transformed the Great Palace from a sprawling villa to a fortified enclosure. The next step in the medievalization of the imperial residence was to remove it from the center altogether at the end of the eleventh century, when it was replaced by the Blachernae Palace in the northern corner of the city.64

ası Camii. Much of the eastern wall is uncertain, but a salvage excavation carried on Küçük Ayasofya Bulvarı turned up a portion of the defensive wall, which now decorates the lobby of the Eresin Crown Hotel.63 The fortification transformed the Great Palace from a sprawling villa to a fortified enclosure. The next step in the medievalization of the imperial residence was to remove it from the center altogether at the end of the eleventh century, when it was replaced by the Blachernae Palace in the northern corner of the city.64

URBAN THEMES IN URBAN BUILDINGS

Significant works of architecture and their decorative programs may reflect aspects of both a civic identity and an urban history, for buildings respond to their environments in many different ways. Individual monuments, if properly read, can tell us as much about the city as can the textual evidence. The early sixth-century church dedicated to Hagios Polyeuktos gives us some sense of how architecture figured in the political discourse of the day.65 Although the church lay in ruins by the thirteenth century, the excavations revealed vast substructures and a rich array of ostentatious architectural details, including the famous marble niche heads formed by the spreading tails of peacocks. As the excavator, Harrison, has argued, Hagios Polyeuktos replicated the Temple of Solomon in its measurements, translated into Byzantine cubits: measuring 100 royal cubits in length, as was the Temple, and 100 in width, as was the Temple platform – following both the unit of measure and the measurements given in Ezekiel 42:2–3. Harrison estimates the sanctuary of the church to have been 20 royal cubits square internally, the exact measurement of the Holy of Holies, as given in Ezekiel 41:4. Similarly, the ostentatious decoration compares with that described in the Temple; if we let peacocks stand in for cherubim, as Harrison suggests, cherubim alternate with palm trees, bands of ornamental network, festoons of chainwork, pomegranates, network on the capitals, and capitals shaped like lilies.66

A powerful noblewoman, Anicia Juliana was one of the last representatives of the Theodosian dynasty, who could trace her lineage back to Constantine. When her son was passed over in the selection of emperor in favor of Justin I and subsequently Justinian, the construction of Hagios Polyeuktos became her statement of familial prestige. It was the largest and most lavish church in the capital at the time of its construction. The adulatory dedicatory inscription credits Juliana with having “surpassed the wisdom of the celebrated Solomon, raising a temple to receive God.”67

As the immediate predecessor of Justinian’s Hagia Sophia, the rediscovered church of Anicia Juliana emerges as part of a monumental discourse, in which political rivalries within the city were expressed in the language of architecture. The grander scale and the transcendental interior of Hagia Sophia may be viewed as Justinian’s response to Anicia Juliana’s presumption. Similar symbolic readings might be proposed for Justinian’s church, as the Temple of Solomon or even as the Throne of God from the vision of Ezekiel. Justinian’s famous, if legendary, exclamation at the dedication, “Solomon, I have vanquished thee!” may have been directed more toward Juliana than toward Jerusalem.68 Procopius uses similar Temple-like language about Hagia Sophia, insisting that God “must especially love to dwell in this place which He has chosen.”69 The architectural discourse was ultimately more about the divinely sanctioned authority of emperors following the model of Old Testament kings than about sacred topography. Clearly, both Juliana and Justinian understood the symbolic value of architecture, with which they could make powerful political statements. In the case of Hagios Polyeuktos, it was both a statement that could not be put into words and one that would never be repeated.70

In the case of Hagia Sophia, however, the underlying allusion to the Temple took many directions beyond simply eclipsing the prestige of a rival. As a New Temple rebuilt by Justinian at the heart of Constantinople, it symbolically transformed the city into a New Jerusalem, emphasizing its sacred character, without necessarily replicating its forms.71 It also bolstered Justinian’s claims to imperial authority, grounding his rule in the divinely sanctioned kingship of the Old Testament.

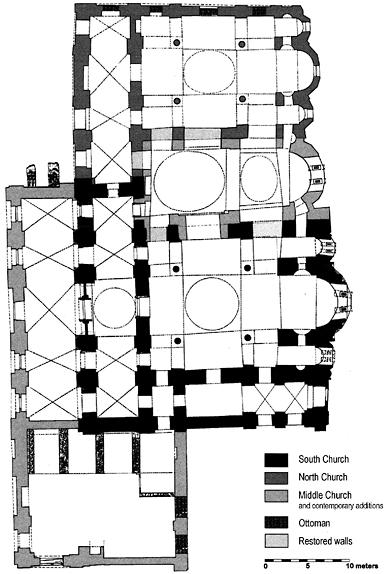

A second example is provided by the monastery of Christ Pantokrator, now known as the Zeyrek Camii, built originally c. 1118–36 by the emperor John II Komnenos and his consort Eirene. It was perhaps the most significant Byzantine architectural undertaking of the twelfth century (Figure 25.5). In addition, the typikon survives, giving us some sense of the use of the building in the twelfth century. The general outline of the Pantokrator’s Byzantine history is well known, with three churches built side by side in rapid succession.72 The south church was constructed first to be the katholikon, or main church of the monastery, dedicated to Christ Pantokrator. Largest, most lavishly decorated and best preserved of the three churches, the south church represents the largest cross-in-square church of the Byzantine period, with a dome more than 8 meters in diameter, rising 24.5 meters above the floor. Its plan, with lateral aisles, measured approximately 100 × 100 Byzantine feet – that is, the same dimensions as the dome bay of Hagia Sophia. Almost upon completion of the south church the complex was enlarged. To this a second cross-in-square church was added to the north, dedicated to the Virgin Eleousa, which was open to the laity and served by a lay clergy. Finally, the curious, twin-domed funeral chapel of St Michael was sandwiched between the two churches.

The rapid transformation of the monastery through its eighteen-year construction history is particularly interesting, as formal concerns shifted from monumentality to complexity. The founders clearly intended to situate it within the urban context of the city, as is evident both from its prominent visual position and from the typikon, which redirects the Friday urban processions between Blachernae and the Chalko-prateia churches, so that the important icons (signa) could be brought into the Pantokrator to participate in the imperial memorial services.73 Similarly the famed icon of the Theotokos Hodegetria was to be brought annually to the monastery to commemorate the day of John’s death.74

Larger concerns are also evident in the funeral chapel, which the typikon refers to as the heroon.75 Destined to be the dynastic mausoleum of the Komnenoi, the oddly archaic term heroon – meaning a hero’s shrine – calls to mind the monumental martyria of the early Christian period, of which the Holy Apostles was the nearest example. Nikolaos Mesarites employed the term heroon in reference to the imperial mausoleum at the Holy Apostles, explaining that those buried there are heroes.76 The mausoleum of Constantine the Great and his successors lay just up the hill from the Pantokrator, perhaps visible from the monastery’s entrance. By the time of its completion in 1136, the Pantokrator had developed into an irregular five-domed

Figure 25.5 Zeyrek Camii (Christ Pantokrator), plan drawn by R. Ousterhout.

complex, which also may have been intended to visually equate the Pantokrator with the five-domed church of the Holy Apostles. In its final form, it would seem to be a part of an elaborately constructed imperial ideology, designed to bolster the claims of the Komnenos family to the legitimacy of their rule, to ground them in Byzantine history. Their success in this world was as much a concern as their salvation in the next.

In a final example, the rebuilding and decoration of the monastery of the Chora, now known as the Kariye Camii, c. 1316–21, we can read the architecture and decoration as part of a discourse with the Byzantine past and its urban identity. One of the oldest religious foundations in the city and formerly under imperial patronage, the church was completely enveloped and lavishly decorated by Theodore Metochites, who was prime minister of the empire and one of the great humanist scholars of the fourteenth century. Metochites’ building is as complex as Hagia Sophia is monumental and perhaps followed the model of the Pantokrator in its church-cluster plan.77 In the building program we find new architectural additions artfully set against older elements, which were left exposed. I would argue that the lack of integration, the contrast, the juxtaposition of old and new, were intentional. The new portions may be understood as a response to history, an attempt to establish a symbolic relationship with the past.78 The new additions never obscure the older edifice but are joined to it in a way that seems to respect its character. The domes of the naos and the funeral chapel are aligned, and the detailing of the older apse is reflected in that of the newer. Moreover, the builders seem to have been inspired by the difficulties of adding to an older building, to design around, but to maintain the integrity of, the historical core of the monastery. The masons would appear to be addressing not just new functional considerations, but also the symbolic significance of the historical setting.

As a scholar Theodore Metochites had a great concern with the past and with his position in history. The significance of the site’s history that underscores the architectural design is also reflected in the mosaic decoration, perhaps seen most clearly in the Deesis mosaic, which depicts Christ and the Virgin, to whom the church and monastery were dedicated, with the two previous imperial benefactors kneeling at their feet. The mosaic thus spells out Metochites’ lineage as founder, perhaps most obviously in the “family resemblance” between Prince Isaac Komnenos in the Deesis mosaic and Metochites in the adjacent dedicatory panel.79 These two portraits establish a sort of visual dialogue with the past that corresponds to the architectural relationships.

The mosaic program places the Chora monastery under the protection of the Virgin Mary, while reinforcing her role as the guardian of the city. The monastery was dedicated to the Virgin, and in his poetry Theodore Metochites referred to both monastery and Virgin as his protection and refuge. These ideas are expressed visually in the image of the Virgin positioned above the main entrance to the church, where she is depicted with Christ in her womb.80 The image repeats the significant features of a miraculous protective icon of the Virgin that was kept at the nearby imperial church of the Blachernae, where the sacred relic of the Virgin’s robe was also kept. Traditionally regarded as the sacred palladia of the city, both the robe and the icon were paraded around the walls when the city was under siege – that is, the Virgin, represented by the robe and icon, provided spiritual protection and was capable of turning back invading armies.81 In the Chora image, the Virgin’s cascading robes frame the view looking westward into the monastery courtyard. Normally a dedicatory image like this one would be placed leading into the church. That role is taken by a pendant image of Christ, for the main church was dedicated to Him. But the monastery proper was dedicated to the Virgin, and that explains her odd positioning. Moreover, the view westward was toward the land walls, which would have been visible in the fourteenth century, and the image of the Virgin could be read in association with them. The Virgin was thus the protector of both Theodore Metochites and his monastery – and she was also the protector of the city and its walls. Like the Blachernae church, the Chora offered a spiritual outpost for the defense of the city. Late Byzantine coins often show the Virgin surrounded by the walls of the city, emphasizing her civic role. Thus, in spite of Constantinople’s transformation and decline, the image of the Virgin of the Chora can be read in a broader civic context. It testifies to the fact that Constantinople retained an urban identity and a civic consciousness into its final period.

CONCLUSIONS

Although we may see the radical transformation of the city and its monuments, it is remarkable how the Byzantines often failed to recognize the changes around them, or, at the very least, failed to reflect the change in their writings. The triumphal entry celebrated by Basil I in 879, which is recorded in detail, could easily have taken place several centuries earlier. But what about its settings? Although the Golden Gate continued to function for occasional triumphal entries, its defensive function was gradually given precedence, evident in the reduction and blocking of the passageways.82 Basil enjoyed two ceremonies outside the walls and stopped for ten receptions between the Golden Gate and Hagia Sophia.83 Following a military parade into the city, Basil was acclaimed by both factions and the demarchs in appropriate ceremonial dress. The cortege proceeded through the city on horseback, stopping for acclamations and receptions at the Sigma, the Exakionion, the Forum of Arcadius, the Forum Bovis, the Capitol, the Philadelphion, the Forum of Theodosius, the Artopolia and the Forum of Constantine. There they dismounted and were met by the patriarch outside the church of the Theotokos, which Basil had founded. After changing into civilian garb, they continued on foot to the Milion, and to Hagia Sophia. Finally they proceeded to the Great Palace, according to the usual ceremonial movements, terminating in a banquet.

What is perhaps most remarkable here is that with the exception of the church built by Basil, all monuments or public spaces used in the ceremony were preiconoclastic; most were Roman in character. While the rhetoric surrounding Basil emphasized his renewal of the city, we are given no indication of the condition of the monuments and monumental spaces. The appearance of continuity is emphasized, but the ceremony may mark a transformation from actual order to symbolic order. The text of rituals like Basil’s entry may demonstrate the gap between the desires and realities of Byzantine society. At the beginning of this chapter, I suggested that we as scholars know Byzantine Constantinople more as a concept than a reality. One wonders if this was true for the Byzantines as well.

In contrast to this willful avoidance of the present reality, late Byzantine patriographic writings offer a more transparent view.84 Most important among these works is the Byzantios, an oration in praise of Constantinople composed by Theodore Metochites, the patron of the Chora monastery, recently discussed by Paul Magdalino.85 Magdalino emphasizes that the rhetorical attention to the city’s past greatness coincides with the period of revival under Michael VIII and Andronikos II.86 Indeed, Metochites seems to recognize the diminished state of affairs, but he gives it a positive spin: Constantinople as a city is constantly regenerating itself. By way of comparison, he points out that as birds molt, new feathers appear amid the older plumage; in an evergreen plant, losses are not fatal but are replaced by new growth. In a like manner Constantinople renews itself, he argues, so that ancient ruins are woven into the city’s fabric to assert their ancient nobility amid the new constructions. Similarly he notes how the ruins of the city are recycled in new constructions both within the city itself and, as evidence of the city’s generosity, in other cities as well. The intended message of Metochites’ encomium is of unchanging greatness, implying that the new creations replicate the pattern of their predecessors, while glossing over the more tawdry realities of ruin and spoliation. For Metochites the writer, Constantinople could be simultaneously eternal and a city in transition. Metochites the patron of architecture might have had a somewhat different perspective. For the modern viewer and reader, it is hoped that archaeology and philology, texts and material culture, taken in equal doses, might offer a balanced view of the medieval city.

NOTES

1 A distant ancestor of this essay was presented at the Illinois Program for Research in the Humanities at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where I held a fellowship in 2001. I am grateful for their support.

2 For a general discussion of ekphraseis see Maguire 1981; for their application to architecture, see Ousterhout 1999: 33–8; also Webb 1999.

3 Mango 1985; Dagron 1974; Dagron 1984; Magdalino 1996a; Magdalino 2007a. Because of the illustration limit, this essay must sadly follow suit.

4 Müller-Wiener 1977; Mathews 1976.

5 Karamut 2007.

6 Müller-Wiener 1977: 312; Mango 2001: 24–5; but see M. Gökçay in Karamut et al. 2007: 170–4; R. Asal in Karamut et al. 2007: 180–215.

7 Müller-Wiener 1977: 255–65; Bauer 1996: 167–203; Berger 2000: 167–8.

8 Kriesis 1960: 322–7; Baldini-Lippolis 1994: 279ff.

9 For a recent attempt at reconstructing the street system, see Berger 1987; Berger 1997; Berger 2000.

10 For the literary references, see the summation of Fenster 1968: 20–86.

11 Mango 1985.

12 For the Roman monuments, see Platner and Ashby 1929; for the Holy Apostles and its foundation, see Mango 1990.

13 For Ilion/Troy as an alternative site, see Theophanes 1883: 23; Zonaras 1841–97: III, 13–14.

14 Stupperich 1982: 210–35, who associates the Trojan iconography with civic identity; see also Bassett 1996.

15 Malalas 1831: 321; Mango 1993.

16 Bassett 2004; see also Rose 1998: 98–100.

17 Delehaye 1923: 1–94, at 8.10–11, pp. 11–13.

18 See e.g. Sherrard 1965, with chapters entitled “The New Rome” and “The New Jerusalem.”

19 See the discussion by Wortley 1982: 254; Maraval 1985: 92–104; Wortley 2006.

20 Heisenberg 1922: 27; see Magdalino 2004.

21 For a reconsideration of the “Jerusalem question,” see Ousterhout 2006b: 98–116; and Ousterhout forthcoming; also Flusin 2000.

22 Mango 1985: 53 and passim.

23 Mango 1985.

24 Magdalino 2007a, for much of what follows.

25 Mango and Scott 1997: 607–9.

26 Ousterhout 2001b: 5, 8.

27 Brubaker and Haldon 2001: 20–1.

28 Foss and Winfield 1986: 54.

29 For the remains incorrectly identified as the Bryas Palace at Küçükyalı, see now Ricci 2003.

30 Mango 1951; Foss and Winfield 1986: 70–1.

31 Mango 1951; see also Ousterhout 1998.

32 Mango 1985; see also Ousterhout 1997: esp. 39–41.

33 Manners 1997.

34 Van der Vin 1980: I, 254.

35 Naumann and Belting 1966; more recently, Akyürek 2002.

36 Lavin 1962: 19; Zonaras 1841–97: II, 591–2.

37 AASS, Sept., V: 275; Naumann and Belting 1966: 23–4.

38 Mathews 1971: 61–7.

39 Mango 1999. I thank Jordan Pickett for his observations on Hagia Euphemia.

40 Naumann and Belting 1966: 49–53; with limited remains, the dates of the mausolea remain uncertain.

41 Naumann and Belting 1966: 112–94.

42 Thomas 1987.

43 Magdalino 2007a.

44 Constas 2006; Snively 2006; Saradi-Mendelovici 1988.

45 Talbot 1993 does not discuss Euphemia; for the period in general, see Geanacoplos 1959.

46 Striker and Kuban 1997: 32–100.

47 Striker and Kuban 1997: 95; reiterated by Striker 2001.

48 Not noted by Berger 2000: 170.

49 Striker 1981: 13–16, and pl. 26; Janin 1969: 351–4.

50 For a critique of the western medieval perspective of Byzantine architecture, see Ousterhout 1996.

51 Magdalino 1984: esp. 102–5; I have discussed this relationship in the context of Cappadocian settlements: Ousterhout 2006a: 176–81; Morris 1995: 92.

52 I am grateful to Danuta Gorecki for discussions on this subject; see Gorecki 1981: esp. 209–10; Thomas 1987: 37–8, 133–6; Charanis 1948: esp. 115.

53 Morris 1995: 151; Thomas 1987: 133–6.

54 Striker 1981: 6.

55 Grierson 1962: 3–60.

56 Striker 1981: 9.

57 Grierson 1962: 59.

58 Striker 1981: 29–31.

59 Underwood 1966: vol. I, 280–99.

60 Müller-Wiener 1977: 225–8; Mango 1997; Bardill 1999, which includes the latest bibliography.

61 See most recently, Asutay-Effenberger 2004.

62 Mango 1997; Mango 1995.

63 The excavation is unpublished but its excavator Metin Gökçay promises a report shortly.

64 Müller-Wiener 1977: 223–4.

65 Harrison 1986: 410–11; Harrison 1989.

66 Harrison 1986: 410–11; Harrison 1989.

67 Harrison 1986: 5–7.

68 Dagron 1984: 303–9; Harrison 1989: 276–9.

69 Procopius, Buildings, I.i.61–2.

70 Ousterhout forthcoming. Recent studies have offered a more nuanced history to the architectural discourse; see Bardill 2006, with a thorough bibliography; note esp. 339–40.

71 Ousterhout 2006b.

72 Ousterhout et al. 2000; Ousterhout et al. forthcoming.

73 Pentcheva 2006a: 165–73.

74 Pentcheva 2006a: 173–7.

75 The following is summarized from Ousterhout 2001a: esp. 149–50.

76 Downey 1957: esp. 892 and 915: XL.1.

77 Ousterhout 2002.

78 Ousterhout 2000, for much of what follows.

79 Cf. Underwood 1966: II, pls 26 and 36.

80 Underwood 1966: II, pl. 20.

81 Pentcheva 2006a: 145–63.

82 Müller-Wiener 1977: 297–300; Mango 2000.

83 Constantine Porphyrogennetos 1990: 140–7; McCormick 1986: 154–7, 212–30.

84 Fenster 1968: 185ff.

85 Vienna, Nationalbibliothek, Codex Vind. Phil. Gr. 95, 274v–275r; recently discussed by Magdalino 2009.

86 Magdalino 2009.