CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT

THE MEDIEVAL PROGENY OF THE HOLY APOSTLES

Trails of architectural imitation across the Mediterranean

Tassos Papacostas

And thus during the reign of the illustrious doge of the Venetians, Vitale Faliero, the church of the evangelist Mark in Venice, which had been founded by the most noble doge Domenico Contarini, was completed in a skilful construction entirely similar to that of the Twelve Apostles at Constantinople.1

This is how in the early twelfth century the recently rebuilt church of San Marco was described by a monk at the Venetian monastery of San Nicolò di Lido. His statement provides the clearest contemporary evidence for a direct relationship between the Justinianic church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople and a medieval structure. Modern scholarship has linked the late antique Apostoleion to various churches in Apulia, on Cyprus, and as far west as Aquitaine. In addition, direct links between these medieval monuments, which share the common defining feature of a nave covered by a sequence of domes, have also been postulated. It is these links that the present brief study proposes to investigate in order to establish their nature and to challenge some long-held assumptions. Although not central to medieval architectural history, the issue is of considerable importance because it enables us to explore contacts between Constantinople and regions both within and outside the empire, and to assess the impact of Byzantine architecture beyond the empire’s frontiers.

THE HOLY APOSTLES AND SAN MARCO

The first structures on the site of the Holy Apostles, a mausoleum and a cruciform timber-roofed basilica, were erected in the fourth century. The basilica housed the relics of Timothy, Luke and Andrew, translated there in 356–7, setting a precedent that was to be emulated countless times. In the mid-sixth century the basilica was replaced by a vaulted structure and a second mausoleum was added. Throughout these centuries and down to 1028 the complex received the sepulchres of numerous Byzantine emperors. As repository of the most important relics after those of the Passion and privileged venue for imperial burials it combined two of the most symbolically charged functions a shrine could fulfil, ranking second only to the patriarchal and imperial church of St Sophia. Today virtually nothing remains of the late antique buildings, which were demolished shortly after the Ottoman conquest to make room for the construction of the Fatih Camii.2 Nevertheless, the appearance of the sixth-century church has been reconstructed on the basis of a number of texts and surviving or excavated monuments that adopted the same architectural scheme.

Like its fourth-century predecessor, the Justinianic church was a cruciform structure. According to Prokopios the crossing that housed the sanctuary was crowned by a fenestrated dome while four blind domes covered the cross arms which were furnished with colonnades (and thus aisles) on both ground and gallery level. Later on in his account of Justinian’s building activities Prokopios states that the contemporary church of St John at Ephesus, also rebuilt over an earlier structure, was very similar in all respects to that dedicated to the Holy Apostles.3 Although he does not describe it in any detail, St John has been excavated and indeed confirms the sixth-century author’s testimony. The two churches differ primarily in that at Ephesus there was an apse to the east and an additional domed bay to the west, increasing the number of domes to six.4 Like the Constantinopolitan monument, St John also had apostolic connections as it housed what was believed to be the tomb of John the Theologian, and thus became a major pilgrimage shrine.

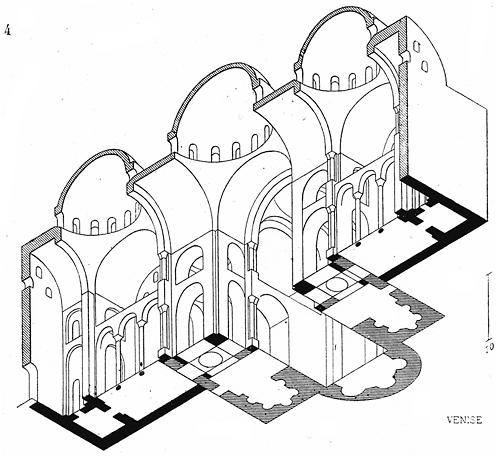

Further indications concerning the architecture of the Holy Apostles come from a later period and a much more distant area. San Marco in Venice was likened to the Holy Apostles as early as the twelfth century. Like its presumed model, the structure whose construction was initiated under Doge Domenico Contarini, probably in 1063, adopted a cruciform layout with domed bays and colonnades (although not at gallery level). The similarities between the eleventh-century San Marco and the sixthcentury Holy Apostles are obvious. It is far less clear whether these were the result of an intention to imitate a prestigious model or were imposed by the earlier church on the site. The architecture of the latter, built shortly after the translation of the relic of St Mark from Alexandria in 829, has been the subject of much debate for a long time and a consensus has yet to emerge; it will continue generating arguments and proposals as long as the archaeological evidence remains fragmentary.5 Otto Demus in his magisterial study of the monument left several options open, pointing out the inconclusive nature of the evidence and cautiously suggesting that the ninth-century church may have been a timber-roofed or a vaulted (and domed) cruciform building, parts of which were incorporated within the eleventh-century structure; he also showed that the building campaign that followed the fire of 976 was only a restoration and not a complete rebuilding.6 The latter remains one of the few points on which more recent scholarship appears to be in agreement.

In the 1990s a multiplicity of views concerning the architecture of the original church and its relationship to the present structure were put forth. John Warren argued for an idiosyncratic domed cross-in-square nave with atrium and a tripartite sanctuary with large protruding apses, the nave subsequently incorporated within the later structure and constituting its central domed bay. This reconstruction was rejected outright by Rowland Mainstone who, based on observations concerning the masonry in the crypt and the static behaviour of the vaults, does not accept that the present central domed unit may belong to an earlier phase and implies that the church was entirely rebuilt in the eleventh century. Finally Peter Megaw, partly agreeing with Warren and relying primarily on the plan of the crypt and irregularities in the layout of the central domed unit, tentatively suggested that even more of the original structure survives today within the Contarini church. His reconstruction consists of two domed units, corresponding to the present central and western bays, with a flat east wall (no apses) and short north and south transepts (without domes) where the domed cross arms now stand.7

It is not the aim of this chapter to resolve the vexed question of the ninth-century structure, but rather to address the relationship of San Marco with the Holy Apostles (taken for granted for the eleventh-century church in view of its early attestation), and whether this may go back to the original building on the site.8 Did the builders and patrons of the first San Marco have in mind the Constantinopolitan church when they were erecting theirs? And if so, what does this tell us about the Holy Apostles? Mainstone does not propose a reconstruction of the ninth-century building and therefore his argumentation affects the question only to the extent that it lends support to the intentional adoption for the eleventh century. Warren’s suggestion would exclude any link with the Holy Apostles in the ninth century. Megaw’s, on the contrary, would support an initial intention (truncated cruciform layout with two domes) that was fully realized only with the later reconstruction, more in line with Demus’ conclusions.

The question raised by all suggestions is, of course, why the Holy Apostles? What led the rulers of Venice in either the ninth or the eleventh century to select an antiquated architectural model from Constantinople for their principal church? This was after all not a type in use at the time within the empire, and other cases of exported Byzantine architecture in the medieval period show adoption and adaptation of contemporary rather than earlier types (e.g. the early churches of Kiev). The question has been largely answered, at least as far as the eleventh-century church is concerned, with reference to local conditions and politics in Venice, to its relations with Byzantium, and to the obvious apostolic and imperial connections of the Holy Apostles.9 Indeed, the Apostoleion continued housing the precious relics translated in the fourth century and the imperial tombs in the two mausolea. But by the time the second San Marco was built it was no longer used for imperial burials, the last having taken place there several decades earlier (Constantine VIII in 1028). The various functions of San Marco and the Holy Apostles overlap only in their apostolic dimension. The Venetian shrine was also a palatine and coronation church, which the Constantinopolitan building obviously was not; the latter, on the other hand, housed the sepulchres of numerous emperors whereas few doges were buried in San Marco. Thus, it may be argued that the funerary function was not deemed as important as the apostolic link, although of course it represented ancient tradition going back to Constantine. Could there be additional factors that affected the selection of the Holy Apostles?

In a seminal study published in 1942 Richard Krautheimer examined the concept of the copy in western medieval architecture as evidenced primarily by Romanesque buildings, which were said in contemporary sources to have been modelled on the rotunda of the Anastasis at the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. He concluded that a few elements such as the dedication, a particular measurement, the number of supports or the circular layout sufficed to earn a building the epithet “copy” of the prestigious model and to associate it with the latter in contemporary minds.10 The close relationship between San Marco and the Holy Apostles is obviously very different from the paradigm established by Krautheimer. So much so that a relatively minor element has come to play an important role in discussions concerning the fate of the Holy Apostles in the medieval period. The element in question is the appearance of the domes. As we have already noted, in the Justinianic church the central dome was lit while those of the cross arms were blind. At San Marco, on the other hand, all five domes have windows. This has prompted the suggestion that the Constantinopolitan church may have undergone substantial alterations to its superstructure in the medieval period; in other words, that the lit domes of San Marco reflect faithfully those of the Holy Apostles as they appeared in the eleventh century. The evidence, consisting of two descriptions of the church (by Constantine the Rhodian and Nicholas Mesarites) and of twelfth-century manuscript illuminations, is inconclusive.11 A major campaign of reconstruction and redecoration of the Apostoleion in the middle Byzantine period might partly explain the Venetians’ predilection for the refurbished apostolic shrine. It nevertheless remains conjectural. Eleventh- and twelfth-century members of the imperial family founded monasteries in which they were eventually laid to rest (Peribleptos, Kosmidion, St George of Mangana, Pantokrator, Kosmosoteira), abandoning a centuries-old tradition of burials in the two mausolea of the Holy Apostles. Had the latter undergone extensive repairs, presumably with imperial patronage, would it be abandoned so quickly?

AQUITAINE

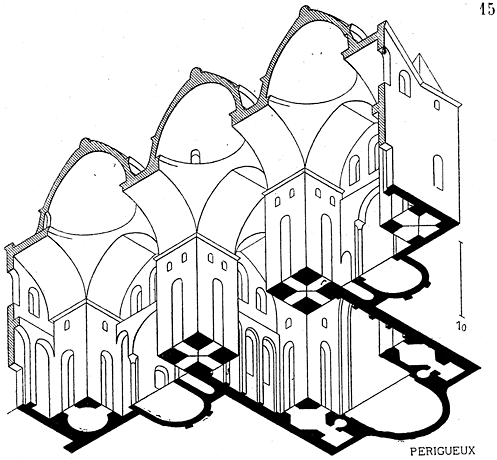

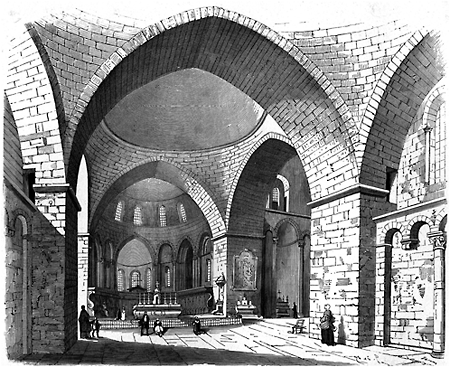

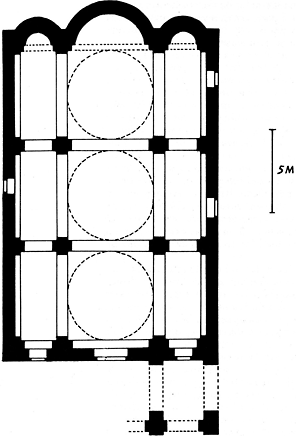

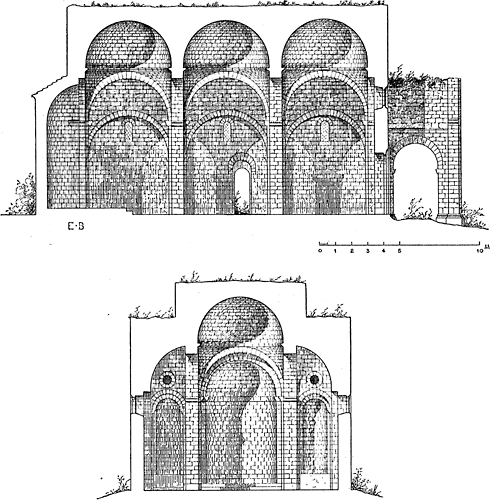

The twelfth-century church of Saint-Front at Périgueux in Aquitaine has been linked to both San Marco and the Holy Apostles (Figures 28.1, 28.2). It is an equally exceptional case insofar as it falls clearly outside Krautheimer’s model of medieval imitation. Even the most cursory look at the plan and elevation reveals that it follows rather closely the same model (“San Marco translated into stone” according to Auguste Choisy).12 Although excessively and arbitrarily restored in the second half of the nineteenth century, its main traits are still easily discernible: the cruciform centralized structure has one dome over each cross arm and an additional dome over the crossing on quadripartite piers but no colonnades or galleries, simplifying even further than San Marco the Holy Apostles scheme. Originally the church was entered through the eastern wall where later an apse was erected. The peculiar layout was due to the existence of an earlier and smaller timber-roofed basilica on the site (consecrated in 1047); its choir had perhaps been replaced in the eleventh century by a domed bay that was subsequently incorporated within the cruciform structure as its western arm when this was erected after a fire damaged the earlier building in 1120 (the church was finished by 1173).13 Under this early choir, and therefore in the present western cross arm, was located the tomb of the shrine’s titular saint, venerated in medieval times as the first bishop of the local see and founder of Christianity in Périgord (Figure 28.3). As André Grabar noted, this of course is reminiscent of both the Holy Apostles and especially San Marco, with its role as repository of the relic of a saint associated in the medieval period with the spread of Christianity in the region in Roman times.14

The architecture and function of Saint-Front, although built using local techniques and initially a monastic church (it only became the city’s cathedral in the seventeenth century), leave little doubt about its affiliation. What remains less secure

Figure 28.1 San Marco, Venice: isometric section, after Choisy 1899.

is the actual origin of its model: purely Byzantine or filtered through Venice? The arguments for both were put forth as early as the nineteenth century.15 Although in the case of Venice the familiarity with Constantinople, its shrines and their symbolism that led to the conscious imitation of an especially prestigious model is not particularly surprising, the same cannot be said of distant Périgueux, far removed from the cultural orbit of medieval Byzantium. Indeed, Otto Demus has plausibly argued that the presence of Venetian merchants in southern France in the twelfth century, the movement of pilgrims and the relative proximity of Venice (compared to Constantinople) may go some way in tilting the balance in favour of San Marco, built only a few decades earlier.16

The importance of Saint-Front, however, extends beyond the importation of an architectural scheme either directly from Byzantium or through Venice, to a much larger group of domed monuments whose architecture has been associated with the Byzantine East. In the region stretching from the Garonne in the south to the Loire in the north no fewer than seventy-seven mostly aisleless churches with naves covered by a series of domes are known to have existed, sixty surviving today in various states of preservation and dating mostly to the twelfth century; half of these are

Figure 28.2 Saint-Front, Périgueux, France: isometric section, after Choisy 1899.

located in the Périgord.17 A lot has been written about the origins of the use of domes in the religious architecture of this large area, the debate having been particularly lively in the early twentieth century.18 The various arguments revolved around the role played in the formation of this tradition by local building practice and by external input. The imported model reasoning was much favoured and remained largely prevalent throughout the twentieth century. It was prompted by the ostensibly sudden appearance of domed schemes and their subsequent concentration in that particular area of south-western France.

Had the domes of the cruciform church of Saint-Front been the earliest in date (as Félix de Verneilh had suggested), the subsequent proliferation of domed bays could be explained as a result of their introduction in the architecture of an influential pilgrimage shrine. The domed cruciform structure of Saint-Front, however, was clearly not the first instance of their use; the earlier domed choir of the timber-roofed basilica housing the saint’s tomb perhaps provided a precedent. So did a number of other churches, all with naves consisting of two or more bays covered by pendentive domes, with lateral walls often articulated by blind arcades and without aisles but

Figure 28.3 Saint-Front, Périgueux, France: ground plan, after Conant 1978.

sometimes with a transept; they all date to either the same period or earlier than Saint-Front. One is situated not far from the great cruciform shrine itself: it is the original cathedral of the town, Saint-Étienne-de-la-Cité. Other prominent examples include Saint-Avit-Senieur, the cathedral of Saint-Pierre at Angoulême, and the transept churches at the abbeys of Souillac, Solignac and Fontevrault in the Loire valley, the northernmost representative of the type, dedicated by Pope Callixtus in September 1119.19

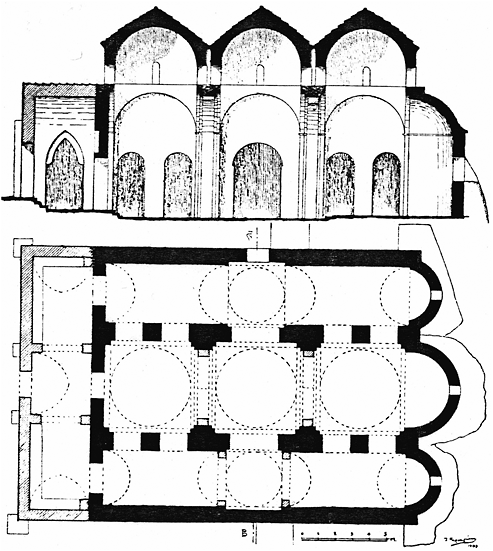

One of the most important monuments of the group is the cathedral of SaintÉtienne at Cahors (Figure 28.4). Also consecrated by Callixtus II in July 1119, less than two months before Fontevrault, its nave with two domed bays (the choir is covered by a rib vault) was thought by Raymond Rey to represent the earliest specimen and indeed the prototype of the domed nave in the region as it was attributed to the late eleventh century on account of a sudden increase in recorded donations and of changes in the administrative organization of the local church. The bishop of Cahors, Géraud III de Cardaillac, was responsible for the undertaking.20 He is known to have travelled to the East where he spent three years, visiting first Constantinople together with Bertrand of Toulouse and then the county of Tripoli, returning home in late 1112; he died one year later. A precious relic first attested in the cathedral in 1119, namely a piece of cloth believed to have been used to cover the head of the dead Jesus, is traditionally linked with the bishop’s pilgrimage. Camille Enlart, rejecting Raymond Rey’s early dating and insisting on the “caractère absolument oriental” of the cathedral, connected its construction with the bishop’s journey, suggesting that the domed scheme must have had something to do with the shrines

Figure 28.4 Saint-Étienne, Cahors, France: ground plan, after Vidal et al. 1969.

visited by de Cardaillac and his entourage. Much more recently Marcel Durliat, broadly agreeing with Enlart’s dating, tentatively explained the construction of the church in terms of the religious fervour caused by the arrival of the relic: the apse was begun soon after the bishop’s return and was completed by 1119; the construction of the two domed bays of the nave followed.21

Enlart went further, casting doubts over the early dating of the other domed churches of Aquitaine and arguing that Cahors remained the prototype for these monuments (although not for Saint-Front, for which he admitted a possible link with either the Holy Apostles or St John of Ephesus). As we just saw, however, there is little doubt that pendentive domes were already being used in the ecclesiastical architecture of the region before the pilgrimage of Géraud de Cardaillac. More importantly, Enlart proposed a specific group of Byzantine monuments as the ultimate source of inspiration for Cahors and consequently for the other domed churches of the region, namely the multi-domed churches of Cyprus which he first brought to the attention of modern scholarship. This suggestion merits particular attention as it is often cited but rarely scrutinized.22

First, there is absolutely no evidence that the bishop of Cahors visited the island during his pilgrimage, although of course this is not to be excluded considering that some of the major sea lanes to the Holy Land passed through Cypriot ports. Second, the monuments in question are not situated anywhere near the main ports of call, which in this period were Paphos and Limassol. The principal Cypriot churches that Enlart claims may have influenced the architecture of buildings such as the cathedrals at Cahors and Périgueux and the abbey churches at Souillac and Solignac are St Barnabas outside ancient Salamis near Famagusta on the island’s east coast, St Lazaros at Larnaca and the much altered katholikon of the nearby monastery of Stavrovouni.23 Although in later centuries all three are attested as pilgrimage shrines popular with visiting travellers, in the twelfth century neither Famagusta nor Larnaca are known to have been major gateways into the island (this would happen in the later thirteenth century for Famagusta and even later for Larnaca). The fivedomed church at inland Peristerona is too remote to be considered in this context, while the related structure at Yeroskepou (discussed below), although near Paphos and therefore presumably more accessible, is not known to have ever been a goal of pilgrimage.

Enlart noted certain similarities between Cahors and domes on Cyprus: their austere character, the pointed arches supporting them, the rectangular piers with plain imposts, the small number of dome windows and the horizontal masonry courses of the pendentives (Figures 28.5, 28.6). But restoration and further research carried out subsequently have revealed that the number of dome windows is in fact large in some of the most important Cypriot multi-domed churches (fourteen at each of the two domes of St Barnabas), and the pointed arches represent later efforts to underpin the original round arches.24 The architectural similarities between these Cypriot and the French churches are superficial, due largely to their common characteristic, namely the domed nave. Aside from the unsurprising differences in building techniques and methods due to local traditions and materials, there is also an obvious difference in scale. The largest Cypriot domes do not exceed 6 metres in diameter (St Barnabas, St Lazaros), whereas those of the main French monuments range from approximately 11 metres at Angoulême and 12 at Saint-Front to 15 at Saint-Étiennede-la-Cité and 18 at Cahors. Moreover, the lack of aisles in the Aquitanian monuments with their wide naves contrasts sharply with the basilical layout and compact arrangement of those on Cyprus.

The master masons of south-western France did not need the example of Cyprus to inspire them in the construction of their domes, which ultimately stemmed from the local tradition, albeit initially employed for smaller rural buildings.25 Visual contact with early Byzantine domed structures may have encouraged the use of largescale domes, and the construction of Saint-Front definitely gave further impetus to

Figure 28.5 Saint-Éloi, Solignac, France: view of the nave, after Verneilh 1851.

this trend. However, it should be stressed that the domed naves of Aquitaine represent only a fraction of the architectural output of the region in this period and that the dome is, after all, nothing more than one vaulting solution among many others. Its spread in this particular area may appear anomalous within the context of Romanesque architecture; but its extensive use may have more to do with the foundation of large churches during this period which, it should be remembered, marks the transition from Romanesque to early Gothic architecture with all that this entails in terms of experimentation in vaulting solutions.

APULIA

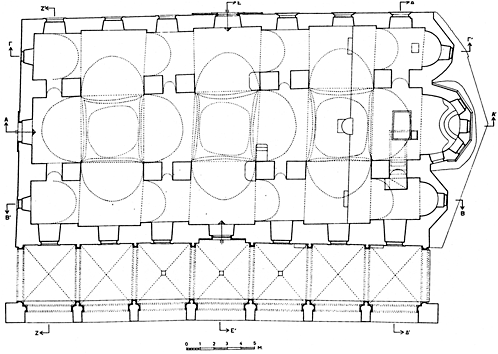

A parallel and contemporaneous development with surprisingly analogous effects occurred in Apulia. Here too a cluster of multi-domed churches has been associated with the Byzantine East. Located primarily in the Terra di Bari, its main representatives constitute a much smaller and compact group of half a dozen monuments along the Adriatic coast. The earliest known specimen appears to be the cathedral of San Sabino at Canosa. A much altered transept basilica, it still preserves its nave (with aisles), crossing and transepts covered by a total of five domical vaults (Figure 28.7). The cruciform layout and number of ‘domes’ have of course prompted comparisons with both San Marco and the Holy Apostles, first discussed by Émile

Figure 28.6 St Barnabas, Salamis, Cyprus: view of the nave, after Enlart 1919–24.

Bertaux in his monumental survey of medieval south Italy. Bertaux noted the equally obvious differences between Canosa and the Venetian and Constantinopolitan monuments: the layout with one dome bay for each of the transept arms and the crossing and two for the nave results in a Latin rather than Greek cross plan.26 Moreover at Canosa all five domes are in fact low domical vaults while the aisles are cut off from the spacious nave by a heavy low arcade on piers. The latter feature was used by George Soteriou to compare San Sabino to the five-domed churches of Cyprus (Peristerona and Yeroskepou), and to suggest a direct relationship between them.27 The Cypriot monuments, however, although sharing the number of domes in a cruciform layout, do not have transepts; the lateral domes are lower and merely interrupt the barrel vaults of the aisles (perhaps a later addition at Yeroskepou) while in the interior no cruciform layout is recognizable (Figure 28.8).28 Bertaux, on the other hand, suggested that the layout of San Sabino was perhaps inspired from San Marco, as at the time the Apulian monument was thought to date to the very end of the eleventh century, but also contemplated the possibility that it may have been the Holy Apostles that provided the model. Unlike San Marco and Saint-Front, in this case the copy would conform to Krautheimer’s paradigm, as it does not replicate closely its model but merely reproduces its main feature, in this case the five domes.

More recently Annabel Jane Wharton reopened the dossier of San Sabino reassessing both its date and its relationship with Constantinople. She argued for an earlier date, in the middle decades of the eleventh century and thus before the construction

Figure 28.7 San Sabino, Canosa, Italy: ground plan, after Belli d’Elia 1987.

of San Marco, based on the evidence of surviving marble church furnishings and the masonry (alternating brick and ashlar courses).29 As in the case of both San Marco and Saint-Front, the selection of the Holy Apostles model was explained through the apostolic links of the Apulian see. Canosa’s first bishop was allegedly Felix, a

Figure 28.8 SS Barnabas and Hilarion, Peristerona, Cyprus: ground plan and longitudinal section, after Soteriou 1940.

contemporary of St Peter. Another important figure in its early history was Sabinus, the eponymous saint of the cathedral, a sixth-century bishop whose relic was perhaps translated from Canosa to Bari in the ninth century, although his see never admitted its loss.30 Unlike San Marco, in the case of San Sabino there is no contemporary source relating its architecture to its presumed model, and the liberal interpretation of the latter’s scheme makes such a connection even more difficult to prove. The arguments presented by Wharton, however, support this scenario. A disparity between the funds available for the construction of the two structures (at Venice and Canosa) may partly account for the differences in the degree of architectural complexity and fidelity to their prototype.

The other multi-domed monuments of Apulia date mostly from the Norman period and do not follow the Canosa scheme. The monastic churches of San Benedetto at Conversano, the Ognissanti of Valenzano and San Francesco at Trani (originally Santissima Trinità), as well as the cathedral of San Corrado at Molfetta, are all three-aisled basilicas without a transept, built in the eleventh to thirteenth centuries (Figure 28.9). Their naves are covered by three pendentive domes (at Molfetta squinch-like niches are inserted between the pendentive zone and the drums of the western and central domes: Figure 28.10) carried on round arches on cruciform piers integrating the narrow aisles into the area of the nave, in sharp contrast to the isolated aisles at Canosa; their aisles are covered by quadrant vaults, abutting most effectively the domes (Figure 28.11).31 As in the case of the Aquitanian domed naves, the origin of their Apulian counterparts has also been the subject of considerable debate. Bertaux was the first to suggest a possible link with, yet again, the multidomed churches of Cyprus. Noting the stone masonry of both groups that differentiates them from the brick architecture of the core provinces of Byzantium and raising the possibility of an Apulian travelling to the island, he nevertheless highlighted their differences, particularly the quadrant aisle vaults and pyramidal dome roofs covered

Figure 28.9 Ognissanti, Valenzano, Italy: ground plan, after Belli d’Elia 1987.

Figure 28.10 San Corrado, Molfetta, Italy: view of the nave, after Bertaux 1904.

with flat stones (chiancarelle) in the Apulian monuments. He also stressed the local antecedents, especially in the vernacular architecture of the region with its wellknown trulli, the structures covered with conical domes built of chiancarelle. Three decades later, Grigore Ionescu revisited the argument and proposed a combination of local building traditions with inspiration from Byzantine models, possibly from Cyprus: an Apulian interpretation of the domed nave. Soteriou came to a similar conclusion although he stressed much more the supposedly Cypriot affiliation, which

Figure 28.11 Ognissanti, Valenzano, Italy: longitudinal and transversal sections, after Bertaux 1904.

he attributed to an alleged transfer of Greek-speaking populations from Byzantium to south Italy in the medieval period.32

However, as in the case of Aquitaine, the ecclesiastical architecture of Apulia, as represented by the multi-domed basilicas with the exception of San Sabino, did not require any direct external input to produce this result. The basilical layout was not foreign to the local tradition; nor was the use of domes. The construction of the probably Byzantine-inspired Canosa cathedral in the mid-eleventh century may have introduced the concept of a dome-covered nave, a concept that entered the local building tradition and was subsequently employed in these smaller basilicas. An example dated to the period following the construction of San Sabino shows that there was indeed considerable experimentation with the early use of domed bays: at the now ruined Santa Maria di Càlena, on Monte Gargano to the north of the region where the monuments mentioned above were built, the original unfinished nave consisted of two bays with domical vaults, similar in form but much smaller than those at Canosa, flanked by quadrant-vaulted aisles.33

CYPRUS

The monuments of distant Cyprus cannot be held responsible for the domed naves of either the Aquitanian or Apulian churches. Like the latter, they constitute a small but far from homogeneous group. Their chronology is anything but settled and deserves a separate study.34 For the purposes of the present discussion it will suffice to point out that they are almost certainly either contemporaneous or earlier than the two western groups, the latest specimen (Peristerona) probably dating to the eleventh or the first half of the twelfth century. St Barnabas at Salamis and St Lazaros at Larnaca, although basilical in plan, present an elevation of juxtaposed domed cross-in-square units on heavy piers that clearly distinguishes them from the Apulian and Aquitanian structures; the illusion of a nave flanked by aisles fostered by the ground plan is eschewed (Figures 28.6, 28.12). Their layout was at least partly conditioned by the earlier buildings which they replaced: the column basilica that stood at St Barnabas in late antique times is attested archaeologically, while at St Lazaros there is some evidence for earlier structures of uncertain function. Thus, their departure from the norms prevailing in the ecclesiastical architecture of the island in middle Byzantine times (domed centralized schemes with, admittedly, an often longitudinal bias) can be largely explained through practical considerations. What is more, in the case of St Barnabas it appears that the multi-domed nave vaulting perhaps replaced an

Figure 28.12 St Lazaros, Larnaca, Cyprus: ground plan, after Papageorgiou 1998.

earlier barrel vault. The partly excavated early medieval successor to the large late antique cathedral of St Epiphanios nearby appears to have been an initially timberroofed basilica that was subsequently vaulted with three domes over its nave; unlike St Barnabas, the superstructure here probably followed closely the ground plan with barrel vaults over the aisles. A combination of the two schemes was employed at the churches of Peristerona and Yeroskepou. As mentioned above in connection with Canosa, in addition to the three domes over their nave, the barrel-vaulted aisles of these churches are interrupted by lower domes, although the latter’s positioning is not reflected in the ground plan; this remains firmly basilical with the aisles isolated from the nave by low and opaque pier arcades. What is more, at least in the case of Peristerona the longitudinal layout may have been conditioned yet again by an earlier structure on the site.

Unavoidably the latter two monuments, because of their number of domes, have been associated with the Holy Apostles (and the related churches at Ephesus and Venice). Enlart was the first to advocate a possible link. Wharton tentatively pursued the argument further in connection not only with the Peristerona and Yeroskepou churches but also with those at Salamis and Larnaca, noting the similarities in the support system of the latter group (each dome on its own set of piers as at San Marco) and their quasi-apostolic associations.35 Indeed, both Barnabas and Lazaros of Bethany were traditionally credited with the foundation of the sees of Salamis and Kition (Larnaca) respectively, and the site of their shrines was thought to house their sepulchre. Yet these are the very structures that lack lateral domes and any pretence to the cruciform and centralized layout of the Holy Apostles. The same holds true of St Epiphanios, housing the relic of the eponymous Church Father. The churches at Yeroskepou and Peristerona, on the other hand, although boasting five domes, have no known link with prominent figures from the early Christian period, the original dedication of the former being uncertain while the latter was dedicated to Barnabas and Hilarion, two obscure fifth-century Cappadocian anchorites. Leaving aside issues of modes of cultural interaction between Constantinople and Cyprus during the period in question, the suggestion of an allusion in their architecture to the Holy Apostles is difficult to accept. The multi-domed schemes of Cyprus are more likely to have resulted from less lofty considerations, related to the existence of earlier structures (that bequeathed their basilical layout to their successors) and, as elsewhere, to experiments with vaulting solutions.36

CONCLUSION

The process that led to the construction of the Apulian structures is comparable but not identical to that observed during the same period in Aquitaine; the impact of San Sabino is slightly different to that of Saint-Front in that the former played perhaps a significant role in establishing the domed nave as the norm, at least among the group of monuments discussed above. The Byzantine East and its domed churches were visited by pilgrims and Crusaders from numerous regions of western Europe that never developed a taste for multi-domed naves. This offers yet another indication of the peculiar conditions prevailing in both Aquitaine and Apulia. As for the idea assigning a defining role to Cyprus, it must be abandoned once and for all. It is untenable in the current state of our knowledge regarding the circumstances of construction of monuments in all areas concerned. Any similarities are almost certainly coincidental and not the result of a process of conscious imitation. For reasons particular to each area (local building traditions and prevalent church schemes, structural considerations) it was deemed appropriate to cover church naves with a sequence of domes. Comparable parameters affected the construction of naves with various types of domes during the same period elsewhere too (San Cataldo and San Giovanni degli Eremiti at Palermo, the Langhauskuppelkirchen of Upper Egypt), surely indicating more than anything else that this was again the result of a legitimate search for structurally sound and functional vaulting.37 This is not to deny the unquestionable importance of the Holy Apostles. But the prestigious model was instrumental in determining the architectural scheme of San Marco, perhaps San Sabino and, indirectly, Saint-Front only. The multi-domed architecture of all other groups of monuments is the result of the unrelated developments outlined above. The lure of Constantinople and its apostolic shrine was certainly strong in the medieval world, and Venice constitutes the most potent case in point. It should not, however, be sought in the multi-domed naves of Cyprus, Apulia or distant Aquitaine.

NOTES

1 Regnante itaque Vitale Faliero, Veneticorum duce egregio, consummata est Venetiae ecclesia evangelistae Marci, a Domenico Contareno, duce nobilissimo, fundata, consimili constructione artificiosae illi ecclesiae, quae in honorem duodecim Apostolorum Constantinopolis est constructa: RHC Occ. 5: 284; Demus 1960: 90; Buchwald 2000: 40–2.

2 ODB 2: 940; Heisenberg 1908; Grierson 1962; Angelidi 1983a; Dark 2002 with earlier bibliography.

3 Prokopios, Buildings I.iv.9–18, V.i.4–6.

4 ODB 1: 706; Thiel 2005.

5 EAM 11: 527–8 for an overview of propositions down to the late 1990s; see also Cecchi 2003.

6 Demus 1960: 65–6, 69, 73.

7 Warren 1990; Warren 1997; Mainstone 1991; Mainstone 1997; Megaw 1996.

8 As implied in Bouras 1997: 169.

9 Demus 1960: 90–9; Buchwald 2000: 40–2.

10 Krautheimer 1942.

11 For opposing views see Krautheimer 1969 (also Krautheimer 1986: 242 and n. 11) and Wharton Epstein 1982.

12 Choisy 1899, 2: 201.

13 Conant 1978: 284, 289–90; Durliat 1979: 309.

14 Grabar 1947: 502 n. 2.

15 Verneilh 1851; Choisy 1899, 2: 51–2.

16 Demus 1960: 95–6; also Bréhier 1927: 245; Conant 1978: 289; and Ousterhout 1996: 21. For a Byzantine, and against a Venetian, origin see Enlart 1919–24, 1: 234.

17 Conant 1978: 284.

18 Bertaux 1904, 1: 386–7; Diehl 1910: 676–7; Diehl 1926, 2: 721; Rey 1925; Enlart 1926; Bréhier 1927.

19 Daras 1942; Daras 1959: 69–90; Daras 1963; Secret 1968: 37–44; Conant 1978: 283–90; Durliat 1979: 304–10.

20 Rey 1925: 8–9; Bréhier 1927: 251; Daras 1963: 55; Vidal et al. 1969: 193–232.

21 Enlart 1926; Durliat 1979: 287–8. An earlier date is suggested in Vidal et al. 1969.

22 Enlart 1899, 2: 706–7; Enlart 1919–24, 1: 106, 233–6; Enlart 1926; and Diehl 1910: 676–7; Diehl 1926, 2: 721; Daras 1963: 55; Conant 1978: 284; Atroshenko and Collins 1985: 78.

23 Enlart 1926: 142.

24 Papacostas 1999, 2: 19–20.

25 Enlart 1926: 134–6; Bréhier 1927: 242–3, 250–1.

26 Bertaux 1904, 1: 378, 386.

27 Soteriou 1940: 409.

28 As noted in Bouras 1997: 168.

29 Wharton Epstein 1983: 81–3; Wharton 1988: 148–9. See also Belli d’Elia 1987: 68–70.

30 Wharton Epstein 1983: 80, 83–5.

31 Bertaux 1904, 1: 375–99; Ionescu 1935; Bertaux 1978, 5: 595–626; Belli d’Elia 1987: 37, 39–40, 42–3, 99–101, 357–63; Wharton 1988: 158–9.

32 Bertaux 1904, 1: 387–95; Ionescu 1935: 124–8; Soteriou 1940: 409. See also Venditti 1967: 108.

33 Ionescu 1935: 69–70; Venditti 1967: 117–18; Belli d’Elia 1987: 42–3.

34 Megaw 1974: 78–9; Wharton 1988: 61–7; Papacostas 1999, 2: 18–20, 27–8, 54–5, 63–4; Papageorgiou 1998; Chotzakoglou 2005: 490–4. The doctoral research by Charles Stewart, recently completed at Indiana University, Bloomington, may shed light on this and related issues.

35 Enlart 1926: 141; Wharton 1988: 66.

36 As argued in  ur

ur i

i 1999: 77.

1999: 77.

37 Cassata and Costantino 1986: 75–6, 113–14; Grossmann 2002: 81–7.