9

Rome and Shapur II

The Persian Expedition of Julian (March-June, 363)

(A)

CHRONOLOGY AND ANALYSIS OF THE SOURCES

The preliminaries

Julian’s desire to avenge the frontier regions which had suffered from the recent Persian incursions and his refusal to discuss peace with an embassy from Persia: Libanius or. XVII, 19 and XVIII, 164. His boast that he would restore Singara: Ephrem, Hymni Contra Julianum II, 15. (On his refusal to defend Nisibis on account of its citizens’ loyalty to the Christian faith, see Sozomen, V, 3, 5=ELF 91). He commanded Arsak (Arsaces), the king of Armenia, to muster a large army and to join him later at a place to be designated: Amm. XXIII, 2, 2, Lib., or. XVIII, 215 and Soz., VI, 1, 2.1 He ordered ships to be built in Samosata: Malalas, XIII,pp. , 21–329, 2 (=Magnus of Carrhae, FGrH 225, F 1). His enquiries at various famous oracles: Theodoret, Historia Ecclesiastica III, 21, 1–4. His intention to establish Hormisdas as ruler of Persia: Libanius, ep. 1402, 3. See also Libanius, ep. 737, 1–3 for an example of Roman optimism concerning the campaign.

From Antioch to Callinicum (5±27 March)

Upon leaving Antioch, Julian headed for Hierapolis via Litarbae2 (5 March),3 Beroea (6 March) and Batnae (8 March). Cf. ELF 98 (= ep. 58, Wright). He was met by a delegation from the Antiochene curia at Litarbae and rejected their requests: ELF 98. See also Libanius, or. I, 132 and XVI, 1. (Malalas, XIII, p. 328, 6–19 suggests that he passed through Cyrrhus, but this is unlikely as Cyrrhus was not on the direct route from Antioch to Litarbae.) A colonnade collapsed at Hierapolis4 and killed fifty soldiers: Amm. XXIII, 2, 6. He remained there for three days and, after crossing the Euphrates, he reached Batnae (i.e. Sarug in Osrhoene) on 12 March: Zos. III, 12, 2. There another fifty soldiers were killed while foraging: Amm. XXIII, 2, 7–8. He came to Carrhae on 18 March after a forced march. Cf. Amm. XXIII, 3, 1 and Zos. III, 12, 2, Malalas, XIII, p. , 4 (=Magnus, F 2). He avoided Edessa because of its strong Christian connections: Theodoret, Historia Ecclesiastica III, 26, 1. At Carrhae he divided his forces: Amm. XXIII, 3, 4–5, Zos. III, 12, 3–5 and Sozomen, VI, 1, 2.5 He feigned a march across the Tigris and at some point between Carrhae and Nisibis he turned south towards Callinicum which he reached on 27 March.6 Cf. Amm. XXIII, 3, 6–7 and Zos. III, 13, 1. The next day he received a delegation of Saracen chieftains who presented him with a gold crown: Amm. XXIII, 3, 8. See also ELF 98, 401D (=ep. 58, Wright). On his refusal to pay them their usual bribe, see Amm. XXV, 6, 10. He was joined by the fleet under the command of Lucillianus:7 Amm. XXIII, 3, 9. See also Zos., III, 13, 2–3.

From Callinicum to Maiozamalcha (April-mid-June)

Julian set off from Callinicum for Circesium where he crossed the river Abora (the Chabur) on a bridge of boats: Amm. XXIII, 5, 1 and Zos. III, 14, 2. At Circesium he received a letter from Sallustius beseeching him to call off the campaign: Amm. XXIII, 5, 4. Leaving Circesium, the army marched southwards along the right bank of the Euphrates and passed Zaitha8 on 4 April (Amm. XXIII, 5, 7 and Zos. III, 14, 2). Julian was urged on by his theurgist/philosopher friends in his retinue to continue the campaign despite adverse omens: Amm. XXIII, 5, 10. Cf. Soc., III, 21, 6. His speech to the troops: Amm. XXIII, 5, 16– 23. See also Malalas, XIII, p. , 18–23 (=Magnus F 2–5). The army entered Assyria and the arrangement of the units for the march is given in Amm. XXIV, 1, 2 and Zos. III, 14, 1. The army passed the deserted city of Dura (Europos) on the opposite bank on 6 April: Amm. XXIII, 5, 8 and 12 and XXIV, 1, 5 and Zos. III, 14, 2. Anatha9 was captured on 11 April after a show of strength. Cf. Amm. XXIV, 1, 6–10, Zos. III, 14, 2–3 and Lib., or. XVIII, 218. On the fate of the prisoners, see Amm. XXIV, 1, 9, Lib., ep. 1367, 6 and Chron. Ps. Dionys., s. a. 674, CSCO 91, pp. , 24–180, 2. On 12 April, the force was struck by a hurricane and some grain-ships were sunk because sluice-gates were breached (through enemy action?) Cf. Amm. XXIV, 1, 11. After this an unnamed city was captured and burnt: ibid. XXIV, 1, 12.

The Persian garrison at the fortress of Thilutha10 decided to remain neutral and was bypassed (? 13 March). Cf. Amm. XXIV, 2, 1–2, Zos. III, 15, 1 and Lib., or. XVIII, 219. Achaiacala11 was similarly bypassed and an abandoned fort was burnt: Amm. XXIV, 2, 2. Cf. Zos., III, 15, 2. Two days later (mid-April), the army crossed the Euphrates at Baraxmalcha12 and entered Diacira13 which had been abandoned: Amm. XXIV, 2, 3 (? 17–19 March). The army then passed by Sitha and (recrossed the river? at) Megia (cf. Zos. III, 15, 3) and reached Ozogardana14 c. 22 April. Cf. Amm. XXIV, 2, 3 and Zos. III, 15, 3. The army rested there for two days. Hormisdas, leading a reconnaissance party, was ambushed by the Persians under the command of the Suren15 and Podosaces,

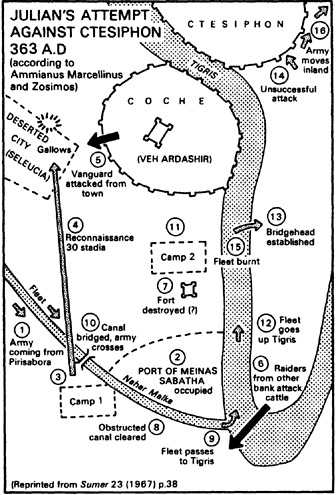

Map 5 Julian’s attempt against Ctesiphon

Phylarch of the Saracens.16 Cf. Amm. XXIV, 2, 4–5 and Zos. III, 15, 4–6. Shadowed by Persian forces (cf. Amm. XXIV, 2, 5), the Roman army reached Macepracta17 near the start of the Naarmalcha (Royal Canal)18: Amm. XXIV, 2, 6 and crossed the canal: Amm. XXIV, 2, 7–8 and Zos. III, 16–17. Pirisabora,19 a key fortress guarding the canal approach to Ctesiphon, was taken after siege (? 27–9 April). Cf. Amm. XXIV, 2, 9–22, Zos., III, 17, 3–18, 6, Lib., or. XVIII, 227–8 and Suidas , s. v.  . See also Eunap., frag. 21 (=Blockley 27, 2, p. 39). On the day after the fall of Pirisabora, a Roman reconnaissance party was ambushed and routed by the Suren. Its commanders were relieved of their command by Julian: Amm. XXIV, 3, 1–2, Zos. III, 19,1–2 and Lib., or.

. See also Eunap., frag. 21 (=Blockley 27, 2, p. 39). On the day after the fall of Pirisabora, a Roman reconnaissance party was ambushed and routed by the Suren. Its commanders were relieved of their command by Julian: Amm. XXIV, 3, 1–2, Zos. III, 19,1–2 and Lib., or.

XVIII, 229. The army marched along the canal past Phissenia20 but the advance was slowed by the Persians breaching the dams and turning the low ground into marsh-land. Cf. Amm. XXIV, 3, 10–11, Zos. III, 19, 3–421 and Lib., or. XVIII, 222–6 and 232–4. At this point the Euphrates was divided into many small streams: Amm. XXIV, 3, 14. In this district they found an abandoned Jewish setlement:22 Amm. XXIV, 4, 1. Julian headed the bridging operation and led his army to Bithra23 where they found the ruins of a palace: Zos. III, 19, 4. Maiozamalcha,24 a well-fortified city, was taken after a laborious siege (? 10–13, May). Cf. Amm. XXIV, 4, 2–30, Zos. III, 20, 2–22, 7 and Lib., or. XVIII, 235– 42. The Romans then passed over a series of canals, and an attempt to stop them by the Persians was foiled: Amm. XXIV, 4, 31.

The relative ease with which the Roman army reached the outskirts of Ctesiphon is briefly mentioned in many other sources. See e.g., Lib., ep. 1402, 2– 3, Eutrop., X, 16, 1, Festus, brev., 28, p. . 18–19, Gregory Nazianzenus, or. V, 9, Socrates, III, 21, 3, Soz., VI, 1, 4, Malalas, XIII, p. , 23–330, 2 (=Magnus, F 3–6) and Zonaras, XIII, 13, 1.

The Roman army at Seleucia/Coche/Ctesiphon

The Romans came upon a palace built in Roman style and left it untouched (? 15 May). They also found the King’s Chase well stocked with game: Amm. XXIV, 5, 1–2, Zos. III, 23, 1–2 and Lib., or. XVII, 20 and XVIII, 243. At the site of the former Hellenistic city of Seleucia,25 Julian saw the impaled bodies of the relatives of the Persian commander who surrendered Pirisabora: Amm. XXIV, 5, 4. Here Nabdates, former Persian commander of Maiozamalcha, who had surrendered to the Romans but had grown insolent, was burnt with 80 men: Amm. XXIV, 5, 4. A strong fortress was captured (? 16 May): ibid. XXIV, 5, 6–11. This could be the Meinas Sabath26 mentioned in Zos. III, 23, 3. The fleet then sailed down the Naarmalcha and the army pushed on to Coche.27 Cf. Amm. XXIV, 6, 1–2, Zos. III, 24, 2, Lib., or. XVIII, 245–7 and Malalas, XII, p. , 10–16 (=Magnus F 7).

Coche and Ctesiphon were both strongly defended: Greg. Naz., or. V, 10. Julian partially unloaded the fleet and used the boats to ferry soldiers across the Tigris: Amm. XXIV, 6, 4–6, Zos., III, 25–6, Lib., or. XVIII, 248–55, Greg. Naz., loc. cit. and Soc., VI, 1, 5–18. See also Eunap., frag. 22, 2 (=Blockley 27, 3, p. 39), Lib., or. I, 133 and XXIV, 37 Festus, brev. 28, pp. , 19–68, 3 and Malalas XIII, p. 330,16–19 (=Magnus, F 8). The Romans were victorious at a battle before the gates of Ctesiphon but were unable to exploit the victory because of ill-discipline. Cf. Amm. XXIV, 6, 8–16, Zos., III, 25, 5–7, Lib., or. XVII, 21 and XVIII, 248–55, Festus, brev. 28, p. 68, 3–7, Greg. Naz., loc. cit. and Sozomen, VI, 1, 7–8. Julian rejected the peace overtures from Shapur II: Lib., or. XVIII, 257–9 and Soc., III, 21, 4–8 (compressed chronology). See also Art. Pass. 69.

A council of war was held (at Abuzatha?)28 and a decision to march inland was made (? 5 June). Cf. Amm. XXIV, 7, 1–3, Zos. III, 26, 1, Lib., or. XVIII, 261. See also Eunap., frag. 22, 3 (= Blockley, 27, 5, p. 41) and 27 (=Blockley, 27, 6, p. 41) and Zon., XIII, 13, 10. The transport fleet was burnt (11–15 June): Amm. XXIV, 7, 3–5, Zos., III; 26, 2–3, Lib., or. XVIII, 262–3, Ephr., HcJul. III, 15, Greg. Naz., or. V, 11–12, Soz., VI, 1, 9, Thdt., h.e. III, 25, 1, Festus, brev. 28, p. , 9, Zon., XIII, 13, 2–9. On the theory that Julian was led astray by one or more Persian double-agents, see Greg. Naz., or. V, 11, Ephr., HcJul. II, 18, Festus, brev. 28, p. 68, 9–10, Soc., III, 22, 9, Soz., VI, 1, 9–12, Philostorgius, VII, 15, Malalas, XIII, pp. 330, 20–332, 21 (=Magnus, F 9–11) and Art. Pass. 69.

A second council of war was held (at Noorda?)29 and the decision to head for Cordyene rather than to return via Assyria was confirmed (? 16 June). Cf. Amm. XXIV, 8, 2–5 and Zos. III, 26, 3. The army struck camp on 16 June: Amm. XXIV, 8, 5. The army marched due north towards the river Douros (Diayala?).30

The Roman withdrawal

The Persians were encountered on the Douros and were defeated: Amm. XXV, 1, 1–3, Zos., III, 26, 4–5 and Lib. or. XVIII, 264. After crossing the Douros, the army marched east (?) towards Barsaphtas: Zos. III, 27, 1. Hucumbra (or Symbra)31 was reached c. 17 June: Amm. XXV, 1, 4 and Zos. III, 27, 2. [The account of Libanius (or. XVIII, 264–7) becomes very vague after the battle on the Douros and mentions only frequent skirmishes, giving no specific details.] The Romans began to suffer from shortage of supplies as the effects of the scorched-earth policy of the Persians were becoming apparent. Cf. Amm. XXV, 1, 10, Zos. III, 26, 4, John Chrys., de S.Babyla XXII/122, Thdt., h.e. III, 25, 4 and Zon. XIII, 13, 13–14. See, however, the denial by Libanius (or. XVIII, 264). The army continued its march up the right bank of the Tigris, passing Danabe,32 Synce and Accete. In between Danabe and Synce the Persians raided the Roman column and lost Adaces, a distinguished satrap, in the skirmish. Cf. Amm. XXV, 1, 5–6 and Zos. III, 27, 4. Accete was reached around 20 June and the Romans again found the crops burnt: Zos. III, 28, 1. The Persians attacked the Roman column as it passed through a district called Maranga (Zos.: Maronsa)33 but were repelled with heavy losses (? 22 May). Cf. Amm. XXV, 1, 11–19 and Zos. III, 28, 2. The Romans however lost some ships because they lagged too far behind: Zos., loc. cit. A truce of three days was agreed upon after the battle: Amm. XXV, 2, 1. Toummara34 on the Tigris was reached probably on 25 June after an exhausting march, during which the Romans regretted the earlier decision to burn the fleet: Zos. III, 28, 3. Another Persian attack was repelled: Zos., loc. cit.

Death of Julian (26 June)

Amm. XXV, 3, Zos. III, 28, 4–29, 1, Lib., or. XVIII, 268–74, Eunap., frag. 20 (=Blockley, 27, 8, p. 41) and 26 (=Blockley 28, 6, p. 45), Festus, brev. 28, p. 68. 11–16, Ephr., HcJul. III, 16, Greg. Naz., or. V, 13–14, John Chrys., de S.Babyla XXII/123, Soc., III, 21, 9–18, Soz., VI, 1, 13–16, Thdt., h.e. III, 25, 5–7, Philost., VII, 15, Malalas, XIII, pp. 331, 21–333, 6 (=Magnus, F 12–15), Art. Pass. 69.

Election of Jovian (27 June)

Amm. XXV, 51–7, Zos. III, 30, 1, Eunap., frag. 23 (=Blockley, 28, 1, pp. 41–2), Greg. Naz., or. V, 15, Soc., III, 22, 1–5, Soz., VI, 3, 1–6, Thdt., h.e. IV, 1, 1–6, Philost., VIII, 1 and Malalas, XIII, p. 333, 7–17. The withdrawal resumed: Amm. XXV, 6, 1. A Persian attack was repelled: ibid. XXV, 6, 2–3 and Zos. III, 30, 2–4. The body of Anatolius,35 killed in the same battle as Julian, was recovered at Sumere and buried. Cf. ibid. XXV, 6, 4 and Zos., III, 30, 4. A few days later the army found refuge at Charcha36 (? 29–30 June) and on 1 July it reached Dura37 (not Europos), where they were delayed for four days by Persian attacks. Cf. Amm. XXV, 6, 9–11. The Romans seized a bridge-head on the opposite bank of the Tigris by a daring raid, but the raging current prevented the Tigris from being successfully bridged. Cf. Amm. XXV, 6, 11–7, 4 and Zos. III, 30, 4–5.

The peace negotiations (? 8±11 July)

Amm. XXV, 7, 5–14, Zos. III, 31, 1–2, Soc., III, 23, 7–8 and Ps.-Joshua the Stylite, Chronicle 7, trans. W.Wright, pp., Malalas, XIII, pp. 335, 1–336, 10 and Zon. XIII, 14, 4, 6. See also Lib., or. XXIV, 9. After the terms were settled, the Roman army continued its withdrawal via Hatra, Ur, (Singara) and Thilsaphata: Amm. XXV, 8, 4–12. At Thilsaphata,38 the expeditionary force met up with the diversionary force under Procopius and Sebastianus: Amm. XXV, 8, 16. The surrender of Nisibis (? 25 Aug.): Amm. XXV, 8, 13–15 and 9, 1–3, Zos., III, 33, 1–34, 1, Eunap., frag. 29, ed. and trans. Blockley, pp. (=John of Antioch, frag. 181), Ephr., HcJul. II, 16–III, 8, John Chrys., de S. Babyla XXII/ 123, Philost., VIII and Malalas, XIII, pp. 336, 11–337, 2.

(B)

THE SOURCES (IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER OF THEIR AUTHORS)

Agathias, historiae IV, 25, 6–7: In the twenty-fourth year of his (i.e. Shapur II’s) reign the city of Nisibis fell to the Persians. It had long been subject to the Romans, but Jovian their own emperor yielded it and gave it up. For Julian the previous Roman emperor had suddenly been killed while actually in the interior of the Persian kingdom, and Jovian was proclaimed by the generals and the armies and the rest of the throng there. 7. And since he had only just come to the throne, and affairs were naturally disturbed—and all this in the middle of enemy country too—he could not under these circumstances devote much time to settling the present situation. So, in order to rid himself of the need to stay in a strange and hostile country and wanting nothing so much as to return home quickly, he made a shameful and disgraceful truce, so bad that it is even now harmful to the Roman state, by which he made the empire contract into new boundaries and cut off the outer parts of his own territory.

(Cameron, p. 125)

Ammianus Marcellinus, XXIII, 2–XXV, 8. See Introduction, p. .

Artemii passio 69–70 (69.1–70.5, pp. 243–4, Kotter): Julian set out from Antioch with all his forces and marched against Persia. When he had arrived at Ctesiphon, he thought after accomplishing this great feat he would go on to other mightier deeds. The accursed emperor did not realize that he had been tricked. For having acquired a devilish devotion to idolatry and hoping through his godless deities to hold his emperorship for a long time and to become a new Alexander, and to overcome the Persians and to obliterate the name of the Christians for all time, he fell victim to his overweening purpose. For he met an aged Persian and was led astray by him (on the promise) that he would without trouble succeed to the kingdoms of the Persians and all their wealth; he drew him into the Carmanian desert, into trackless regions, ravines and desert-like and waterless areas with all his army. And when he had exhausted them with thirst and hunger and killed off all their cavalry, the Persian willingly confessed that he had led them astray so that they might be destroyed by him and he might not see his own native land laid waste by its worst enemies. Therefore they straightway cut this man up limb from limb and dispatched him to his death. But immediately, in this state of distress, they encountered against their will the army of the Persians. A battle occurred and while Julian himself was rushing here and there and organizing his men, he fell to the spear, so it is said, of a soldier; but, as others record, to the spear of a Saracen serving with the Persians. But in the true Christian version which is ours, the spear belonged to the Lord Christ who was ranged against him. For suddenly a bow from the skies stretched taut and launched a missile at him as at a target and it pierced through his side, and wounded him in the abdomen. And he wailed deeply and woefully and thought that our Lord Jesus Christ was standing before him and exulting over him. But he, filled with darkness and madness, received his own blood in his hands and sprinkled it into the air, and when he became breathless shouted out, saying: ‘You have won, Christ. Take your fill, Galilaean!’ Thus he ended his life in a most fearful and hateful manner after many reproaches had been heaped upon his own gods. 70. When the transgressor fell in the no-man’s land around the army, Jovian was proclaimed emperor by the army. He made a peace treaty with the Persians by which he handed over Nisibis without its inhabitants to the Persians. He then departed from there for the army was being destroyed by hunger and disease.

(Dodgeon)

Cedrenus, i, pp. 538, 16–23 and 539, 16–21: Having marched into Persia, he (Julian) was tricked by certain deserters into burning his ships. Afterwards he marched to his satisfaction through desert and rough country, and began to run out of all the necessities and provisions. The men with him began to suffer great distress. When the time for war arrived, while he went around the camp and drew up his men, he was struck with a lance from an unknown direction in the lower abdomen and as a result moaned aloud. He took the blood into his hand and sprinkled it into the air, saying, ‘You have won, Christ! Be satisfied, Nazarene.’…

He (Jovian) was proclaimed emperor by the whole army in the place in which the Transgressor was destroyed. He was tall in stature, so that not even one of the imperial robes fitted him. After one encounter in battle, peace was declared in unison (as at God’s command) both by the Romans and the Persians, and it was specified to last for thirty years.

(Dodgeon)

Chronicon ad AD 724 (Liber Calipharum), CSCO 6, pp. 133, 14ff. (Syriac): In the year 674 (Sel.=AD 363), the defiled Julian descended into the land of the Chaldaeans, to Bet Aramaye, where his ruin came about at the hand of the Romans (sic)…(and Julian was slain) on the twenty-seventh day of the month Iyyar (=May) of the year 674.

In the month of Haziran (=June) in the year 674 on a Friday by the bank of the great river Tigris, on the north side of Kaukaba (= Coche?) and Ctesiphon, in the region called Bet Aramaye39 Jobininus (i.e. Jovian) assumed the great crown of the Roman Empire, and he made peace and concord, and put an end to the hostilities between both the mighty empires of the Romans and the Persians. However, in order that there should be peace between them and that he should free the Romans from the straits in which they were, he gave to the Persians all the area of the east belonging to Nisibis, certain of the villages which surround the city and the whole of Armenia together with the regions subject to Armenia (?)40 itself. (The inhabitants of) Nisibis went into exile in the territory of the Edessenes in the month of Ab (August) in the year 674 and Nisibis was handed over to the Persians devoid of its inhabitants.

(Lieu, revised Brock)

Chronicon Ps.-Dionysianum, CSCO 91, p. , 23–180, 8 (Syriac): In the year 674 (Sel.=AD 363), the emperor Julian descended into Persia and devastated the entire region from Nisibis as far as Ctesiphon in Bet Aramaye. He took a large number of captives from there and settled them at Mt. Snsw. In the same year he died in Persia, struck by a dart thrown through the air. Jovian, commander of his army, then reigned in his place. He made peace between the two empires and ceded Nisibis to the Persians. The persecution came to an end in Persia because of the peace he made and all the churches were (re)opened. All the inhabitants of Nisibis went into exile to Amida in Mesopotamia and he constructed walls for them west of the city.

(Lieu, revised Brock)

Ephrem Syrus, Hymni contra Julianum II, 15–22 and 27 and III, CSCO 174, p. , 23–82, 14 and 83, 11–85, 8:41

II

According to the tune ‘Rely on Truth’

15 But he (i.e. Julian) gave omens and promises and wrote and

(sent) to us

that he was setting out and subduing and would lay bare

Persia,

that he would rebuild Singara—the threat of his letter.42

Nisibis [was taken] through his descent (into battle),

and by his diviners [he brought low] the host who believed in

him;

like a (sacrificial) lamb the city saved his camp.

RESPONSE: Blessed be he who blotted him out and saddened

all the sons of error.

16 (God) had appointed Nisibis, which was taken, as a mirror

so that we might see in it how the pagan, who had set out (i.e. for Persia)

because he took what was not his, lost what was his—

that city which proclaimed to the world

the disgrace of his diviners43 and that [his] shame was

unending;

(God) had delivered it to a steadfast, untiring herald.

17 This is the herald who, with four mouths, cried out in the earth

the shame of his diviners,

and the gates, that during the siege were opened, also unlocked

our mouth to the praise of our redeemer.

Today the gates of that city are shut fast

so that through them the mouth of the pagans and the erring

is closed.

18 Let us seek the reason how and wherefore

they yielded that city, the shield of all cities.

The insane one (i.e. Julian) raved and set on fire his ships near

the Tigris.

The bearded ones deceived him,44 and he did not perceive it,

he the goat who avowed that he knew the secrets;

he was deceived in visible things so he was put to shame in the

non-visible.

19 It is the city which had proclaimed the truth of its saviour;

the waters suddenly burst out and smote against it,

earthworks were brought low and elephants were drowned.

The (Christian) king by his sackcloth had preserved it,

the tyrant by his paganism debased the victory

of the city which prayer had crowned with triumph.

20 Truth was its wall and fasting its bulwark.

The Magians came threatening and Persia was put to shame through them,

Babel through the Chaldaeans and India through the

enchanters.

For thirty years truth had crowned it

(but) in the summer in which he established an idol within the

city

mercy fled from it and wrath pursued and entered it.

21 For empty sacrifices rendered void its fullness;

demons of the waste laid it waste with libations;

the (pagan) altar which was built uprooted and cast out

that sanctuary whose sackcloth had delivered us (i.e the city).

festivals of frenzy reduced to silence its feast, because the sons of error ministered, they made void its

ministrations.

22 The Magian who entered our place, kept it holy, to our shame,

he neglected his temple of fire and honoured the sanctuary,

he cast down the altars which were built through our laxity,

he abolished the enclosures, to our shame,

for he knew that from that one temple alone had gone out

the mercy which had saved us from him three times….

27 While the (our) king was a (pagan) priest and dishonoured our

churches,

the Magian king honoured the sanctuary.

He doubled our consolation because he honoured our

sanctuary,

he grieved and gladdened us and did not banish us.

(God) reproved that erring one through his companion in

error,

What the priest abundantly defrauded, the Magian made

abundant restitution.

III

According to the same tune

1 A fortuitous wonder! There met me near the city

the corpse of that accursed one which passed by the wall;

the banner which was sent from the East wind

the Magian took and fastened on the tower45

so that a flag might point out for spectators

that the city was the slave of the lords of that banner.

RESPONSE: Praise to him who clothed his corpse in shame.

2 I was amazed as to how it was that there met and were present

the body and the standard, both at the same time.

And I knew that it was a wonderful preparation of justice

that while the corpse of the fallen one was passing,

there went up and was placed that fearsome banner so that it

might proclaim that

the injustice of his diviners had delivered that city.

3 For thirty years Persia made war in every way

and was not able to cross the boundary of that city.

Even when it was breached and lying low, the Cross went down

and saved it.

There I saw a foul sight,

the banner of the captor, which was fixed on the tower,

the body of the persecutor, which was lying on the bier.

4 Believe in ‘Yes and No’, the word that is true,

I went and came, my brethren, to the bier of the defiled one

and I stood over it and I derided his paganism,

I said: Is this he who exalted himself

against the living name and who forgot that he is dust?

(God) has returned him to within his dust that he might know

that he is dust.

5 I stood and was amazed at him whose humiliation I earnestly

observed.

For this is his magnificence, and this his pride, this is his majesty, and this his chariot, this is earth which is decayed.

And I debated with myself why, during his prime,

I did not see in anticipation his end, that it was this.

6 I was amazed at the many who, in order to try to please

the crown of a mortal, had denied him who gives life to all.

I looked above and below and marvelled, my brethren,

at our Lord in that glorious height,

and the accursed one in low estate, and I said: Who will be

afraid

of that corpse and deny the True One?

7 That the Cross when it had set out had not conquered

everything

was not because it was not able to conquer, for it is victorious,

but so that a pit might be dug for the wicked man,

who set out with his diviners to the East;

when he set out and was wounded, it was seen by the

discerning

that the war had waited for him so that through it he might be

put to shame.

8 Know that for this reason the war had lasted and delayed—

so that the pure one might complete the years of his reign

and that the accursed one might also complete the measure of

his paganism.

So when he completed his course and came to ruin,

then (both) sides were glad, then there was peace

through the believing King, the associate of the glorious ones.

9 The Just One was able to finish him off with every way of dying

but he kept him for that fearsome and bitter humiliation

so that on the day of his death there was arrayed before his

eyes everything— where is that divination which gave him assurance, and the goddess of weapons who did not come to help him, and the companies of his gods who did not come to save him?

10 The Cross of him who knows all went down before the army,

it endured and was mocked, ‘He does not save them!’

The king it kept in safety, the army it gave to destruction because it knew that paganism was within them.

Therefore let the cross of him who searches all be praised

for fools without discrimination reproached him at that time.

11 For they did not hold fast to the banner of him who redeems

all;

indeed, that paganism which they exhibited at the end

was evident to our Lord from the beginning.

Although he knew well that they were turning to paganism,

his cross saved them; and when they rejected him,

there they ate corpses, there they became a proverb.

12 When the (Jewish) people were defeated near Ai of the

faint-hearted,

Joshua tore his clothes before the ark of the covenant

and uttered dreadful words before the Most High;

there was a curse among the people and he did not know—

just as there was paganism hidden in the force

while, instead of the ark of the covenant, they were carrying

the Cross.

13 So justice herself had in wisdom summoned him,

not indeed by force did it guide his free will;

through enticement he set out towards that spear to be wounded.

He saw the fortifications which he subdued and he was proud;

but adversity did not incite him to turn back until he had gone down and fallen into the abyss.

14 Because he dishonoured him who had removed the spear of

Paradise,

the spear of justice passed through his belly.

They tore open that which was pregnant with the oracle of the

diviners, and (God)

scourged (him) and he groaned and remembered

what he wrote and published that he would do to the churches.

The finger of justice had blotted out his memory.

15 The king saw that the sons of the East had come and deceived

him,

the unlearned (had deceived) the wise man, the simple the

soothsayer.

They whom he had called, wrapped up in his robe,

had, through unlearned men, mastered his wisdom.

He commanded and burned his victorious ships,

and his idols and diviners were bound through the one deceit.

16 When he saw that his gods were refuted and exposed,

and that he was unable to conquer and unable to escape,

he was prostrated and torn between fear and shame.

Death he chose so that he might escape in Sheol

and cunningly he took off his armour in order to be wounded

so that he might die without the Galilaeans seeing his shame.

17 When he mocked and nicknamed the brethren ‘Galilaeans’:

behold in the air the wheels of the Galilaean King!

He thundered in his chariot, cherubim were carrying him.

The Galilaean made known and handed over

the flock of the diviner to the wolves in the wilderness

but the Galilaean flock increased and filled the earth.

(J.M.Lieu, ap. Lieu, 1986a:112–20)

Epitome de Caesaribus 43: After the administration of the Roman world had been brought under his control, Julian, being excessively eager for fame, set out against the Persians. 2. There he was led by a certain deserter into an ambush and when the Parthians (sic) were pressing him hard on this side and that, he rushed forth from his camp which had just been set up, having snatched up merely a shield. 3. And when he strove with ill-advised eagerness to rally his ranks for the battle, he was struck by one of the fleeing enemy with a lance. 4. He was brought back to his tent and again went out to encourage his men; he suffered a gradual loss of blood and expired around midnight, having stated earlier that he was deliberately giving no instructions concerning the succession, lest, as usually happens in a crowd with competing interests, he would bring hazard to a friend through jealousy, and danger upon the army through political disagreement.... 7. He had an inordinate desire for praise; his worship of the gods was full of superstition. He was more daring than is fitting for an emperor, whose personal safety should be preserved to the utmost for the security of all, and especially in time of war. 8. Thus his rather passionate desire for fame had won him over with the result that neither by earthquake nor by numerous presentiments, by which he was forbidden to attack Persia, was he induced to put an end to his eagerness, and not even the sight of a huge sphere falling at night from the heavens before the day of the war made him cautious.

(Dodgeon)

Eunapius, Fragmenta historica 20–2 and 26–7:

20. (=B 27, 8, p. 41) When the troop of mounted cataphracts over and above four hundred rushed down upon the rear-guard.

21. (=B 27, 2, p. 39) Some of the Parthians had wickerwork shields and wickerwork helmets woven in a traditional manner.

22. (=B 27, 1, p. 39) [He says] that the war against the Persians reached its peak under Julian and that either by invoking the gods or by calculation he comprehended from afar the disturbances of the Scythians, like waves on a smooth sea. Thereupon he says to someone in a letter, ‘The Scythians are now lying quiet, equally, they will not do so in the future’. His forethought for the future extended over such a period that he knew in advance that they would remain quiet only for his own time.

(=B 27, 3, pp. 39–40) [He says] that Julian, having previously revealed the plain before Ctesiphon as an orchestra for war, as Epaminondas said, now paraded it as a stage for Dionysus, providing relaxation and amusement for the troops.

(=B 27, 5, p. 41) [He says] that there was such an abundance of the provisions in the suburbs of Ctesiphon that the overriding danger faced by the troops was that of being destroyed by luxury.

(=B 27, 6, p. 41) [He says] that mankind, besides, seems generally inclined towards and readily given over to envy. And since the troops have no means of taking sides fairly about what is done, ‘From the tower’, they say, ‘they judged the Achaeans’, each one of them desirous of being versed in military matters and possessed of more than usual good sense. To some, then, any matter was the subject of foolishness, but he who followed the arguments right from the beginning went back to his own domain.

26. (=B 28, 6, p. 45) [Concerning the end of Julian the Apostate and Soldier, the reply of the oracle was as follows]

But when that time comes when you shall tame the Persian blood with your sceptre and bring them beneath your rule, driven back as far as Seleucia by your sword, then indeed a chariot bright as fire leads you to Olympus, a chariot swallowed up in the turmoil of whirlwinds and lightning, leaving behind the wretched distress of human limbs. And you shall come to the ancestral halls of the ethereal light, whence you came, led astray to take the form of a human body.

Inspired by such eloquent words as these, and even more by prophecies, they say he was most agreeably exalted above mortal destruction….

There is an oracle which was given to him while he was waiting at Ctesiphon:

(=B 27, 6, p. 41) Zeus, the all-wise, once destroyed a race of Earth-born giants most hateful to the blessed ones who dwell in the Olympian halls. Julian the godlike, Emperor of the Romans, contending for the cities and long walls of the Persians, fighting hand-to-hand, destroyed them with fire and the valiant sword, subdued without pause their cities and many races. Seizing also, with heavy fighting, the German soil of those people of the west he laid waste their land.

(M.Morgan)

B 29, 1 (=John of Antioch, frag. 181, FGH IV, pp. 606–7) He (i.e. Jovian) reigned after Julian…. Coming to Nisibis, a populous city, he spent only two days there. He exhausted all its resources and had neither a kindly word nor an act of philanthropy for the inhabitants. …As I have said, when he became Emperor of the Romans after Julian, he was so eager to enjoy his rank which had befallen him that he ignored everything else. He fled from Persia and hurried to get within (the boundaries of) the Roman provinces in order to proclaim his new found fortune. He ceded to the Persians the city of Nisibis, which had long been subject to the Romans. Therefore they mocked him in ditties, parodies and in the so-called famosi (lampoons) because of his surrender of Nisibis.

(Lieu)

Eutropius, X, 16, 1–2: Julian then became sole emperor, and made war, with a vast force, upon the Parthians; in which expedition I was also present. Several towns and fortresses of the Persians he induced to surrender, and some he took by storm. After laying waste to Assyria, he fixed his camp for some time at Ctesiphon. 2. As he was returning victorious, and mingling rashly in the thick of a battle, he was killed by the hand of an enemy, on the 26th of June, in the seventh year of his reign, and the thirty-second of his life, and was enrolled among the gods.

(Watson, pp. 533–4, altered)

Festus, breviarium 28–9 (pp. 67, 14–69, 6): Julian, who was of proven good fortune against the external enemies of the empire, lacked moderation in the war against the Persians. With great magnificence, as befitting the ruler of the whole world, he raised his menacing standards against the Parthians (sic), and advanced his fleet, stocked with provisions, along the Euphrates. In the course of his intrepid advance, a great many Persian towns and strongholds either surrendered to him or were captured by force of arms. Having pitched his camp opposite to Ctesiphon on the bank where the Tigris joins the Euphrates, he spent the day in athletic contests to relieve the enemy of their watchfulness. In the middle of the night he embarked his soldiers and suddenly carried them across to the far bank. They struggled over the escarpment, where the ascent would have been difficult even in daytime when no one was trying to stop them. They threw the Persians into confusion by the unexpected terror and the armies of their entire nation were turned to flight. The soldiers would have victoriously entered the open gates of Ctesiphon if the opportunity for booty had not been greater than their concern for victory. After winning such great glory, when he received a warning from his retinue concerning the return, he put greater trust in his own purpose and burnt his fleet. He was misled by a deserter who had surrendered for the purpose of leading him astray, and was induced to follow a direct route to Madaeana (Media?). Retracing his route upstream along the Tigris (with the river on his right), he exposed the flank of his troops. When he wandered along the column too incautiously, after the dust was stirred up and he lost sight of his own men, he was pierced through the abdomen as far as the groin by the lance of an enemy horseman. Amidst the excessive loss of blood, when in spite of having been wounded he had restored the ranks of his army, and after a long address to his companions, he breathed forth his lingering life.

29 Jovian took over an army that was victorious in battle but confused at the sudden death of their departed emperor. There was a lack of supplies and a very extensive march ahead of them on their return. The Persians also delayed the progress of the column by frequent sallies, at one moment upon the vanguard, then the rear, also upon the flanks of the centre. After several days were spent, so great was the respect for the name of Rome that the first talk of peace came from the Persians, and the army, consumed by famine, was allowed to be brought back on imposed terms prejudicial to the interests of the Roman state (something which had never happened before): namely, that Nisibis and part of Mesopotamia should be handed over, and in this Jovian acquiesced, being inexperienced in government and more desirous of the emperorship than of good renown.

(Dodgeon)

Gregory Nazianzenus,46 orationes V, 8–13, ed. Bernardi, pp.: Having levied in these parts a double force, one military, the other of the demons who led him on (in which he placed the more confidence of the two), he marched against the Persians, placing his trust rather in his senseless daring than in the strength of his armed forces, not being able to discern, very wise as he was, that courage and rashness however similar they may be in sound,47 are yet widely different from each other in reality as much as what we call manliness and unmanliness…

9. Now, the first steps in his enterprise, excessively audacious and much celebrated by those of his own party, were as follows. The entire region of Assyria that the Euphrates flows through, and skirting Persia, there unites itself with the Tigris; all this he took and ravaged, and captured some of the fortified towns, in the total absence of anyone to hinder him, whether he had taken the Persians unawares by the rapidity of his advance, or whether he was out-generalled by them and drawn on by degrees further and further into the snare (for both stories are told); at any rate, advancing in this way, with his army marching along the river’s bank and his flotilla upon the river supplying provisions and carrying the baggage, after a considerable interval he reached Ctesiphon, a place which, even to be near, was thought by him half the victory, by reason of his longing for it.

10. From this point, however, like sand slipping from beneath the feet, or a great storm bursting upon a ship, things began to go black for him; for Ctesiphon is a strongly fortified town, hard to take, and very well secured by a wall of burnt brick, a deep ditch, and the swamps coming from the river. It is rendered yet more secure by another strong place, the name of which is Coche, furnished with equal defences as far as regards garrison and artificial protection, so closely united with it that they appeared to be one city, the river separating both between them. For it was neither possible to take the place by general assault, nor to reduce it by siege, nor even to force a way through by means of the fleet principally, for he would run the risk of destruction; being exposed to missiles from higher ground on both sides, he left the place in his rear, and did so in this manner. He diverted a not inconsiderable part of the river Euphrates, the greatest of rivers, and rendered it navigable for vessels, by means of a canal, of which ancient vestiges are said to be visible; and thus joining the Tigris a little in front of Ctesiphon, he saved his boats from one river by means of the other river, in all security; in this way he escaped the danger that menaced him from the two garrisons. But, as he advanced, a Persian army suddenly started up, and continually received fresh reinforcements, but did not think it advisable to stand in front and fight it out, without the greatest necessity (although it was in their power to conquer, from their superior numbers); but from the tops of the hills and narrow passes they shot arrows and threw darts, whenever opportunity served, and thus readily prevented his further progress. Hence he is reduced to great perplexity, and, not knowing to what side to turn, he finds out an unlucky solution for the difficulty.

11. A Persian of considerable standing, following the example of that Zopyrus employed by Cyrus in the case of Babylon, then pretended that he had had some quarrel, or rather a very great one and for a very great cause, with his king, and was on that account very hostile to the Persian cause, and well-disposed towards the Romans. He gained the emperor’s confidence through his pretence as follows: ‘Your Highness, what means all this, why are there so many shortcomings in so important an enterprise? What need is there of this provision-fleet, this superfluous burden—a mere incentive to cowardice; for nothing is so unfit for fighting, and fond of laziness, as a full belly, and the having the means of saving oneself in one’s own hands? But if you will listen to me, you will burn this flotilla: what a relief to this fine army will be the result! You yourself will take another route, better supplied and safer than this; along which I will be your guide (being acquainted with the country as well as any man living), and will cause you to enter into the heart of the enemy’s country, where you can obtain whatever you please, and so make your way home; and me you shall then recompense, when you have actually ascertained my good will and sound advice.’

12. And when he had said this, and gained credence to his story (for rashness is credulous, especially when God goads it on), everything went wrong at once. The boats became the prey of the flames. They were low on victuals. Everywhere there was ridicule, and the whole venture resembled a suicide attempt. Hope vanished when the guide disappeared along with his promises. They were surrounded by the enemy and battle waged on all sides. It was difficult to advance and provisions were not easy to procure. In despair, the army became disenchanted with their commander. There was no hope for safety left, but one wish alone, as was natural under the circumstances, the ridding themselves of bad government and bad generalship.

13. Up to this point, such is the universal account; but thence-forward, one and the same story is not told by all, but different accounts are reported and made up by different people, both those present at the battle, and those not present; for some say that he was hit by a dart from the Persians, when engaged in a disorderly skirmish, as he was running hither and thither in his consternation; and the same fate befell him as it did to Cyrus, son of Parysatis, who went up with the Ten Thousand against his brother Artaxerxes, and by fighting inconsiderately threw away the victory through his rashness. Others, however, tell some such story as this respecting his end: that he had gone up upon a lofty hill to take a view of his army and ascertain how much was left him for carrying on the war; and that, when he saw the number considerable and superior to his expectation, he exclaimed, ‘What a dreadful thing if we shall bring back all these fellows to the land of the Romans!’ as though he begrudged them a safe return. Whereupon one of his officers, being indignant and not able to repress his rage, ran him through the bowels, without caring for his own life. Others tell that the deed was done by a barbarian jester, such as follow the camp, ‘for the purpose of driving away ill humour and for amusing the men when they are drinking.’48 Some give this honour to one of the Saracens. At any rate, he received a wound truly seasonable (or mortal) and salutary for the whole world, and by a single cut from his executioner he pays the penalty for the many entrails of victims to which he has trusted (to his own destruction); but what surprises me, is how the vain man, that fancied he learned the future from that means, knew nothing of the wound about to be inflicted on his own entrails! The concluding reflection is for once very appropriate: the liver of the victim was the approved means for reading the future, and it was precisely in that organ that the arch-diviner received the fatal thrust.

(King, pp. 91–7, revised.)

Jerome, chronicon, s. aa. 363–4, p. , 6–20, GCS (revised according to the text of Schoene): Julian, on setting out against Persia, promised our blood to the gods after his victory. Whereupon the Apostate was led by a certain bogus traitor into the desert and lost his army through hunger and thirst. When he incautiously wandered off his ranks, it so happened that he was pierced by a lance from an enemy cavalryman whom he met, and died at the age of thirty-two. Jovian who was primicerius from the (corps of) the domestici was made emperor. Jovian reigned for eight months.

(s.a. 364) Jovian was compelled by the necessity of the events to cede Nisibis and a large part of Mesopotamia to the king of the Persians.

(Dodgeon)

John Chrysostom,49 de S.Babyla contra Julianum et Gentiles XXII (122–4, Shatkin, cf. PG 50.569–70):…For in fact Julian, at the head of an army whose numbers had never been surpassed under any previous emperor, was fully expecting to overrun the whole of Persia on the spur of the moment, as it were, and without any effort. However, he fared as wretchedly and pitiably as if he was accompanied by an army of women and young children rather than men. For one thing, he brought them to such a pitch of desperation through shortage of provisions that they were reduced to consuming some of their cavalry horses and slaughtering others as they wasted away of hunger and thirst. You would have thought Julian was in league with the Persians, anxious not to defeat them but to surrender his own forces, for he had led them into such a barren and inhospitable region that he in fact surrendered without being defeated.

123. Even those who were eye-witnesses or forced to experience the many disasters which befell the campaign could hardly begin to describe the full picture, for it defies description. To come to the gist of the matter, Julian died disgracefully and without honour—for some say that he was mortally wounded by one of his own baggage-bearers, out of resentment at the appalling predicament of the army. Another version says that he died at the hands of an unknown assassin, recounting only that he was struck down and that he requested that he should be buried in Cilicia, where his body remains to this day.

124. When he had perished thus ignominiously, the soldiers, realizing that they were in dire straits, prostrated themselves before the enemies and gave pledges to surrender the most secure of all our fortresses (i.e. Nisibis) which acted as an unbreachable circuit wall to our empire. They were humanely treated by the barbarians and thus a few of them were able to escape and returned home utterly exhausted physically. Though ashamed of what they had agreed upon in the treaty, they were constrained by the pledges to abandon their ancestral captivity. For the inhabitants of that city were treated with hostility by those from whom they would expect to receive favours inasmuch as they, like a bulwark, had placed everyone within a safe haven, always putting themselves forward on behalf of everyone else in the face of all dangers. Yet they were moved to alien territory, abandoning their own houses and fields, and wrenched from their ancestral possessions and suffering all this at the hands of their own kinsmen. Such are the blessings we have enjoyed from this noble prince.

(M.Morgan)

John Lydus, de mensibus IV, 118, p. 155, 23–157, 9: Julian is said by Libanius and the many other augurs to have uttered the Homeric phrase concerning his return from the War against the Persians:

‘I stand in awe of the Trojans and the long-robed Trojan women.’ (Iliad, VI, 442)

After he had crossed the Tigris, he took control of many cities and garrisons of the Persians and in every other respect proved irresistible before the Persians. Nonetheless, he was destroyed by guile and all his army with him. For two Persians cut off their own ears and noses and came and deceived Julian, complaining that they had suffered the indignities at the hands of the Persian king. Nevertheless they were able, if Julian followed them, to bring him to victory over Gorgo herself, queen of Persia. Julian forgot his pressing destiny and at the same time the story of Zopyrus in Herodotus and Sinon in Vergil; he fired his ships by which he was carried along the Euphrates, for the purpose supposedly was not to give the Persians the licence of using them. His army carried some modest supplies and he followed behind his treacherous guides. They led him into an arid and waterless wilderness and revealed their trickery: they themselves —for what else was to be expected?—were destroyed, but the emperor discovered he could neither advance in that same direction nor turn back and he perished in a pitiable manner. When a large part of the army had fallen, the Persians launched an attack upon him as he was sick, but they were worsted and then attacked a second time. Now he did not even have twenty thousand men, when before he had led one hundred and seventy thousand. However, Julian fought most valiantly. One man from the Persian division of the so-called Saracens guessed the identity of the emperor from his purple robe, and cried out in his own language ‘malchan’ (meaning ‘the king’). And he let loose with a swish his scimitar (Gk.:  ) and pierced Julian’s abdomen. Oribasius brought him back to the camp and advised him to make his final settlement, and, after Julian had nominated Jovian as emperor, he died.

) and pierced Julian’s abdomen. Oribasius brought him back to the camp and advised him to make his final settlement, and, after Julian had nominated Jovian as emperor, he died.

(Dodgeon)

Ps. Joshua the Stylite, Chronicle 7 (Syriac): In the year 609 (AD 297–298) the Greeks got possession of the city of Nisibis, and it remained under their sway for sixty-five years. After the death of Julian in Persia which took place in the year 674 (AD 362–363), Jovian, who reigned over the Greeks after him, preferred peace above everything, and for the sake of this he allowed the Persians to take possession of Nisibis for one hundred and twenty years, after which they were to restore it to its (former) masters.

(Wright, pp. 6–7)

Julian (Imperator), ELF 98: (To Libanius) I travelled as far as Litarbae,—it is a village of Chalcis,—and came upon a road that still had the remains of a winter camp of Antioch. The road, I may say, was partly swamp, partly hill, but the whole of it was rough, and in the swamp lay stones which looked as though they had been thrown there purposely, as they lay together without any art, after the fashion followed also by those who build public highways in cities and instead of cement make a deep layer of soil and then lay the stones close together as though they were making a boundary-wall.50 When I passed over this with some difficulty and arrived at my first halting-place, it was about the ninth hour, and then I received at my headquarters the greater part of your (i.e. the Antiochene) senate. You have perhaps learned already what we said to one another and, if it be the will of heaven, you shall know it from my lips.

From Litarbae I proceeded to Beroea, and there Zeus, by showing a manifest sign from heaven, declared all things to be auspicious. I stayed there for a day and saw the Acropolis and sacrificed to Zeus in imperial fashion a white bull…. Next, Batnae entertained me, a place like nothing that I have ever seen in your country, except Daphne; though not long ago, while the temple and statue were still unharmed, I should not have hesitated to compare Daphne with Ossa and Pelion or the peaks of Olympus, or Thessalian Tempe, or even to have preferred it to all of them put together….

Thus much, then, I was able to write to you from Hierapolis about my own affairs. But as regards the military or political arrangements, you ought, I think, to have been present to observe and pay attention to them yourself. For, as you well know, the matter is too long for a letter even three times as long as this. But I will tell you of these matters also, summarily, and in a very few words. I sent an embassy to the Saracens and suggested that they could come if they wished. That is one affair of the sort I have mentioned. For another, I dispatched men as wide-awake as I could obtain, that they might guard against anyone’s leaving here secretly to go to the enemy and inform them that we are on the move. After that I held a court martial and, I am convinced, showed in my decision the utmost clemency and justice. I have procured excellent horses and mules and have mustered all my forces together. The boats to be used on the river are laden with corn, or rather with baked bread and sour wine. You can understand at what length I should have to write in order to describe how every detail of this business was worked out and what discussions arose over every one of them.

(Wright, iii, pp. 201–9)

Libanius, ep. 737: (To Pappos) I rejoice in receiving your letter, not only because the letter from a friend is most welcome, but also because there are signs that your country (i.e. Mesopotamia) is being freed from the enemies. This is exactly what Julian is hoping to achieve. Those who had appeared before (i.e. Constantius and his generals) in the past had made the enemies more audacious. 2. Most worthy Pappos, to rejoice in the present security is justified, so that the smile would not desert the face of him who is accustomed to good cheer. 3. The Persians will act as men who are accustomed to war against the gods customarily do. Every one of them (i.e. the gods) will pick up their arms and attack them (i.e. the Persians) and instruct them to flee. 4. Your son wishes to be a rhetor and his talents are not inferior to his desires. He should therefore learn to be more modest. When one of the young shows this, he draws me and receives more from me than any other. 5. Write to him, therefore, (and tell him) to guard his morals and you would not need to beseech me. (June, 362).

(Dodgeon) Libanius, ep. 1220: (To Scylacius) Although I had not yet ceased from my tears, you cast me into a state of greater lamentation with your letter, so precisely did you discuss both the good things we once enjoyed and the ones we might have had, if one of the gods had given back to us the man who won the victories. 2. For those whom he smote praise him (Julian) more now than those on whose behalf he stood in line of battle. But of these peoples two cities (Caesarea and Antioch) danced for joy, and for one of them I feel ashamed. 3. Yet they can be forgiven. For the man who wishes to be mischievous considers his enemy to be the fellow who does not allow him to be mischievous, and, should it happen that his teacher of morality dies, the man who is unable to be moral rejoices at his freedom now to work mischief. We live in the company of such a crowd that is hostile both to gods and to Julian, about whom you entertain the right opinion when you enrol him among the chorus of the gods. 4. I myself have also come to this conclusion and at the same time I groan when I reckon what hopes were held and what was the outcome. Indeed if he (Julian) is with the Higher Powers, my affairs at any rate are worse. For with regard to my affairs let them be stated as follows. 5. For what would it have been like if he had arrived from Persia and you from Phoenicia, he leading prisoners and you on your way to see the prizes of his labours, and I to speak something about his achievements, a small contribution for his great efforts, and that he should relate his own story! A swarm of jackdaws would have come, food for laughter to you and me, that did not know how to speak but tried to strike others to counter their own ignorance. 6. Such an assembled audience an evil day took from us. Many attacked me with arms and I might never have held out, if he (Mercury) had not hurried me away who also stole away Mars in chains. Now someone in hiding has launched an arrow, and I have been indicted for committing awful crimes, but again one of the gods blunted the missile and I remain at my post and hope to be undisturbed. 7. It would have pleased the archers like these to relax their bowstrings (at Julian) but the land of the Persians has been sufficiently wasted. However, I have been requesting an account of what was done from friends among those who returned and those who it was likely would not neglect a written account of such events. Each said that he had an account and would give it but none did, and not even orally did he inform me, for he who has passed on his way is disregarded, but each man’s zeal is entirely upon his own affairs. 8. Certain soldiers who did not formerly know me, gave me the list of some days and route distances and names of places; but nowhere an account of his achievements that can fully explain, but obscurity and shadow that will be insufficient for (the talk of) the compiler. 9. If indeed you also are eager for this knowledge, apprise me of it and the talk of the soldiers will reach you; for these have written their accounts, but I hoped for others. (AD 363)

(Dodgeon)

Libanius, ep. 1367: (To Modestus) 1. Do you see how far conscientiousness can get you? Previously you had high offices and now you enjoy the same confidence, and in no way did your public responsibility end with the old regime. 2. The reason for this is that at that time you did not belong to those who bought their offices or those who used their offices for purposes of personal gain, even though that would have been possible and those who wanted to be just were laughed at. Clearly, the divine one (i.e. Julian) whom the Persians so hate discovered this and thus accorded to you as a reward for your voluntary poverty the highest office next to that of the Emperor, though to Julian (not the emperor) he gave a task requiring the greatest degree of righteousness, such as Rhadamanthys had. 3. Bithynia may be the limit of his district, but his love carries him over to you; for as such a good friend was close by, he was drawn irresistibly to him. Thus he will enjoy the most pleasant society, but the courier freed me from a great fear into which I had been driven by the tidings which had previously reached here: that in the capital city there was much suffering and many ill deeds. 4. What he did report was that some of those thoroughly despicable people without any home were right out of control, while the larger and better part of the population remained calm. You yourself [he said] had acted impeccably, but had bent before the storm and quickly arranged an understanding. Your return to the town was glorious and marvelled at everywhere, for you were surrounded by masses of people and your praise was in every mouth. Your team of horses could not be seen, it was surrounded by the rejoicing crowd. 5. The (military) courier reported this, but I let it be known, driving out one set of tidings with another, the false with the true. But your letter has crossed the Euphrates, no wonder then that it only arrived late in the Emperor’s hands. 6. The latter is advancing, overrunning the Persian Empire. Where he is at the moment, he alone would know best. The prisoners of war tell us what he is achieving, and they tell that he is making quick progress and that the towns are in ruins. But we do not know what to do with all the prisoners. 7. I have said this to excuse the delay of the (military) courier and to give you joy and myself pleasure. (AD 363)

(Dodgeon)

Libanius, ep. 1402, 1–3: (To Aristophanes) I think that rumour even now has done as of old and has instructed the Greeks in the sufferings of the barbarians; for you know how such a thing was accomplished by it in earlier times, when it announced the victory of the conquering army to an army on the point of battle and gave it heart—if therefore a report has not yet come to you, then let the Greeks know that the descendants of Darius and Xerxes are being punished by them as they see their own cities destroyed by fire— these were the men who two years ago were razing ours to the ground. 2. For when the emperor launched his offensive in the spring in an area which they did not consider, the Assyrians were immediately taken, (also) many villages and a few cities; for there were not many. Then the Persian woke up and was dismayed and fled, but he (Julian) pursued and captured everything without a battle; or rather the majority without a battle; he killed six thousand who came on a reconnaissance and at the same time for a fight, if the chance arose. 3. This is the news from the men who spend their lives on the flying camels—for may their speed be honoured by the title of ‘wings’—and there is a hope that the emperor will come leading (in captivity) the present ruler and handing over the (Persian) government to the fugitive (i.e. Hormisdas)…. (AD 363)

(Dodgeon)

Libanius, ep. 1508: (To Seleucus) I wept over the letter and I said to the gods, ‘What is the meaning of this, o gods?’ And I gave the letter to those among the others whom I particularly trust and I saw the letter having the same effect on them also. For each man calculated the circumstances in which you have been compelled to live, compared with what you deserved to meet with. 2. But I shall tell you with what (thoughts) I reassured both them and myself; and indeed I think this will please you. I was reminded of the famous Odysseus, who, when he had pulled down Troy, was crossing the sea, as you know, but we neither require tree branches before our ‘naked manhood’ nor even would we need them, nor are we berated by the household servants and your household is free of all drunken behaviour. 3. But if you are excluded from cities and their baths, just think how many men, when they can spend their time in the city, choose their pleasures in the countryside and judge them more agreeable than the uproar in town. But if you were Achilles and you had to accompany the Centaur on Pelion, what would you have done? Would you have run off to the city and considered the mountain a misfortune? 4. Do not, by Zeus, beat yourself, Seleucus, nor forget those famous generals who had no sooner put up their trophies than one was in chains, and the others were fleeing into exile. For we learnt those stories (in school) not so we might suffer but so that in a crisis we might gain relief from them. 5. You have now an opportunity to show off your courage and you lament, and although you did not fear the Persians you consider the trees a dread terror; and when you endured the sun along the Tigris but have the shade of foliage in Pontus, you desire the market-places in the towns and say that you are lonely. This should be the last thing to happen to a literary man. For how would you be abandoned by Plato, Demosthenes and that famous band who must stay wherever you wish? 6. Therefore converse with these and compile the history of the war which you promised, and as you regard a prize so great you will be unaffected by your present circumstances. This also made Thucydides’ exile easy to bear, and I would have explained it entirely if you did not well understand it. 7. Be assured that by your writing you will gratify everyone. For in company with many you saw what was done, but of those who saw only you have a voice worthy to record the events.

(Dodgeon)

Libanius, or. I, 132–4: When our city council escorted him on his way with prayers that they might be forgiven the charges against them, he replied that, if heaven preserved him, he would favour with his presence Tarsus in Cilicia. Though I have no doubt that you will react to this’, he went on, ‘by pinning your hopes upon him who will be your envoy, yet he too will have to go there with me.’ Then without a tear he embraced me in my tears, with his gaze now fixed on the ruin of Persia. He sent me a first letter from the frontier of the Empire, and marched on, ravaging the countryside, plundering villages, taking fortresses, crossing rivers, mining fortifications and capturing cities. 133. There was no messenger to tell us of any of these achievements, but we rejoiced just as if we saw them, confident that events would happen as they did, as we looked to him. But here Fortune played her usual trick. The army had revelled in the slaughter and rout of the Persians and in the athletic competitions and horse races, on which the inhabitants of Ctesiphon had gazed from their battlements with no grounds to trust even their thickness of wall: the Persians had decided to come as suppliants with prayers and gifts, knowing that it was against common sense for a man to oppose heaven’s will. Then, as their envoys remounted their horses, a spear pierced the side of our wise Emperor, and with the victor’s blood it drenched the land of the vanquished, and the pursuers it delivered into the hand of the fugitive. 134. It was by means of a deserter that the Persians found their good fortune, but we in Antioch discovered it through no human agency: earthquakes were the harbingers of woe, destroying the cities of Palestine-Syria either wholly or in part. We were sure that by these afflictions heaven gave us a sign of some great disaster, and, as we prayed that our guess should be right, the bitter news reached our ears that our great Julian was dead, that some nonentity held the throne, and that Armenia, and as much of the rest of the Empire as they liked, was in Persian hands.

(Norman, pp. 78–9)

Libanius, or. XVII, 19–22: You should not, then, my dear friend, have rejected the Persian embassy, when it asked for peace and was submissive to your will. But the sufferings of the lands near the Tigris, ravaged and derelict, the victim of many incursions, every one of which caused the transfer of our wealth into Persian hands, diverted your attention. You thought it tantamount to treason to desire peace and to refrain from exacting punishment. 20. But there! Heaven opposed you, or, rather, you tried to exact a punishment disproportionate to the crime. There was the land of Assyria, queen of the Persian domains, shaded with tall palms and other trees of all kinds, their strongest storehouse of gold and silver, with magnificent palaces built therein, with herds of boars, deer and all the animals of the chase contained within their enclosures, with forts towering aloft into mid-air beyond the strength of hostile hand, with villages comparable to cities and with unparalleled prosperity. 21. Here he directed his attack, and he so harried and overwhelmed them, himself all smiles and allowing his troops to make merry amongst it, that the Persians would need to colonize it and a man’s lifetime would not be enough to repair the disaster. Moreover, the incredible ascent of the bank, the night battle that slew a vast number of Persians, the trembling that seized their limbs and, in their cowardice, the vision from afar of the ravaging of their lands—all this was part of the punishment he inflicted upon them.

22. Restore to us then, supreme consul of the gods, your namesake who invoked you so often at the year’s beginning. His colleague, despite his advanced years, you have allowed to complete his year—but he was overcome in its midcourse. And while he lay slain, we at Daphne were worshipping the Nymphs with choric dance and other delights, ignorant of the disaster that had befallen us.

(Norman, i, pp. 263–5)

Libanius, or. XVIII, 212–75: See Introduction, p. .

Libanius, or. XXIV, 9:1 feel that the gods were angered against that emperor (i.e. Jovian) and so he was compelled to make peace on terms such that the enemy gained more than they could ever have dreamed of, the whole of Armenia, the acquisition of the important frontier city (of Nisibis) and many strong fortresses.

(Norman, i, p. 497)

Magnus of Carrhae: see under Malalas.

Malalas, XIII, pp. 328, 5–337, 11: Then he left and went through the city of Cyrrhus against the Persians…. (=Magnus of Carrhae, FGrH 225 F) 1. Marching against Sabbourarsakios (i.e. Shapur II), king of the Persians, the Emperor Julian reached Hierapolis. There he sent [p. 329] for ships to be built in Samosata, a city of Euphratensis, some from wood and others from skins, as the extremely wise Magnus of Carrhae, the historian who was with the Emperor Julian, has noted. 2. He left Hierapolis and came to the city of Carrhae where he found two routes, one leading to the city of Nisibis which once belonged to the Romans, and the other going to the Roman fortress called Circesium which lies between the two rivers, the Euphrates and the Aborras, which the Roman Emperor Diocletian established. Julian then divided his army and sent Nisibis sixteen thousand armed men with two commanders, Sebastianus and Procopius. 3. Julian himself reached the fortress of Circesium and left in that fortress six thousand soldiers whom he found stationed there, together with four thousand additional armed men with two commanders, Accameus and Maurus. 4. He left there and crossed the river Aborras by a bridge while the ships, the number of which was one thousand two hundred and fifty, reached the river Euphrates. 5. He assembled his army, taking with him the magister Anatolius and Salustius the Praetorian Prefect and his magistri militum, and climbed up to a high platform from which he addressed the army, commending them and urging them to fight keenly and in a disciplined manner against the Persians. 6. The Emperor then [p. 330] ordered them to board the ships while he himself went on board the ship which had been prepared for him. He commanded 1,500 brave men from the unit of lancers (lanciarii) and javelin-throwers (mattiarii) to go ahead as advance scouts and gave orders that his standards be carried and that Count Lucianus, a man highly skilled in war, should be with him. This man sacked many Persian fortresses lying along the Euphrates and on islands in the middle of the water and killed the Persians in them. He stationed Victor and Dagalaiphus behind the rest of the boats to guard the host. 7. Then the Emperor set out with all the army through the great canal which joins the Euphrates to the Tigris. He reached the Tigris itself, where the two rivers join and form a great lake and crossed into Persia in the region of those who are called the Mauzanites, near the city of Ctesiphon where the Persian king lived. 8. Then the Emperor Julian, having gained the upper hand, encamped in the plain of that city, Ctesiphon, intending to go on with his own Senate as far as Babylon and take the area there.

9. King Sabbourarsakios, thinking that Julian, the Roman Emperor, was coming via Nisibis, hastened against him with his whole force. Then he was informed [p. 331] that Julian, the Roman Emperor, was behind him, taking Persian regions and that the Roman generals with a large force were coming against him from the front, and, realizing that he was in the middle, he fled to Persarmenia. Then, to avoid being overtaken, he secretly sent two of his councillors with their noses cut off with their consent, to Julian the Roman Emperor, to deceive him. These two Persians, with their noses cut off, came to the Roman Emperor wanting, as they said, to betray the Persian king because he had punished them. 10. The Emperor Julian was deceived by their oaths and followed them with all his army, and they diverted him for one hundred and fifty miles, deceiving him, to a waterless desert until the twenty-fifth day of the month of Desius or of Junius. 11. He found there ancient, fallen walls of a city called Bubion, and another place whose buildings were standing but which was deserted, and this was called Asia. The Emperor Julian entered it with all the Roman army and encamped there. While in this area, they were without food and there was not even any fodder for the animals, for it was a wilderness. When all the Roman army realised that the Emperor had been deceived and had led them astray and brought them to desert areas, they turned to utter disorderliness. 12. On the next day, the twenty-sixth of June, he brought out the Persians who had misled him and examined them. They confessed with the words ‘For the sake of our country and our king, that [p. 332] he might be saved, we gave ourselves to death and deceived you. Now, as your slaves, we die.’ He believed them and did not kill them but gave them his promise if they would lead the army out of the desert area.

13. About the second hour of the same day, the Emperor Julian was walking among the army and urging them not to behave in an undisciplined manner when he was wounded by someone unknown. He went into his tent and died during the night as Magnus, whom we referred to earlier, relates. 14. However, Eutychianus, the historian from Cappadocia, who was a soldier and a vicarius of his unit of the Primoarmeniaci (Legio I Armeniaca ?), and who was himself present in the war, wrote that the Emperor Julian entered Persian territory by way of the Euphrates for fifteen days’ marching. There he was victorious and conquered and took everything as far as the city called Ctesiphon which was the seat of the Persian king. The latter fled to the territory of the Persarmenians, while Julian decided with his Council and his army to set out for Babylon on the next day and to take it by night. 15. While he slept he saw in a dream an adult man, wearing a cuirass, approaching him in his tent near the city of Ctesiphon, in a city called Asia, and smiting him with a spear. Distraught, he awoke and cried out. The eunuchs of the bed-chamber and the body-guard and the unit who guarded the tent arose and came to him with royal torches. When [p. 333] the Emperor Julian realised that he had been fatally wounded in the armpit, he asked them, ‘What is the name of the village where my tent is?’, and they told him that it was called Asia. Then he immediately cried out, ‘O Sun, you have slain Julian’, and having lost blood, he died at the fifth hour of the night in the year 411 of the era of Antiochus the Great.

Then the army, before the Persian enemy should learn of this, went to the tent of Jovian, a count among the officials of the bodyguard (comes domesticorum), who had the rank of a stratelates. They led him—not knowing what had happened —to the royal tent, as if the Emperor Julian wanted him. When they had entered the tent, they held him there and hailed him as Emperor on the twenty-seventh of the month of Desius or Junius before the dawn. The rest of the army, some of which was encamped at Ctesiphon and some at a great distance, did not know what had happened until dawn, because they were some way away. Thus the Emperor Julian died when he was thirty-three years old.

After the rule of Julian the Apostate, Jovian the son of Varronianus became emperor; he was crowned by the army (there) in Persia during the consulship of Sallustius. He was a strong Christian and reigned for seven months.