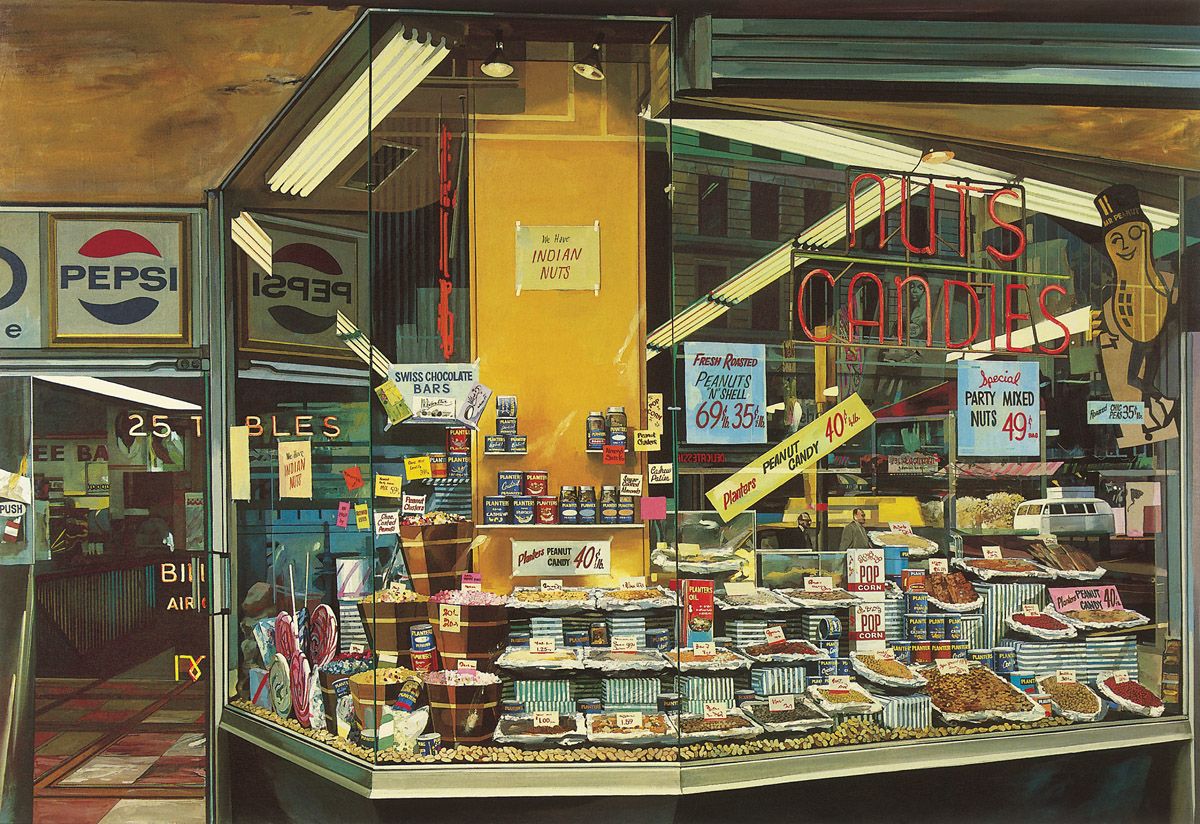

Richard Estes, The Candy Store, 1969. Oil and synthetic polymer on canvas, 121.3 x 174.6 cm. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

Here again our attention is drawn to the self-indulgent treats of modern life in all their formidable plenitude, while the absence of people permits nothing to distract us from the goodies on offer. As always, Estes sorts out the shop-window reflections, while clarifying the confusion of objects and spaces seen through glass.

Ed Kienholz, Turgid TV, 1969. Television, plaster and paint, 51.4 x 25.4 x 57.2 cm. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, California.

This is one of two sculptures Kienholz created in 1969 in which he expressed his evaluation of the standard of most contemporary television broadcasting. Although he often worked with a television playing in his studio, and believed the medium to be a potentially superb means of mass-communication, he felt that it had been hijacked by corporate networks which forced frantic consumerism, mindless programming and tendentious news upon their public. In the work not shown, namely Cement TV (Nancy Reddin Kienholz collection), the sculptor crammed the inside of a portable television with cement dust to denote that the airwaves are often densely filled but communicate nothing. In the present work a large, dark-brown form not unlike a huge lump of excreta oozes from the front of a television casing. The connection of the television and the turd is, of course, strengthened by the punning title of the piece. Naturally, such a statement might seem somewhat banal but culturally it is certainly on target, especially in America where, as Bruce Springsteen has memorably reminded us, there are usually “57 channels and nothing on.”

Duane Hanson, Supermarket Shopper, 1970. Fibreglass, polychromed in oil, with clothing, accessories, supermarket packaging and trolley, 166 cm high (life-size). Ludwig International Forum für Kunst, Aachen. Art © 2006 Estate of Duane Hanson/ Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Duane Hanson was born in Alexandria, Minnesota, in 1925. He first studied art at Macalester College, St Paul, Minnesota, where he received his BA in 1946, and then studied sculpture at the Cranbrook Academy, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, where he held his first exhibition in 1951. Between 1953 and 1960 he lived in Germany, where he showed his work in Bremen in 1958. After returning to the United States to live in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1973 he finally settled in Davie, South Florida. His first New York exhibition was held at the OK Harris Gallery in 1970. Subsequently he mounted many shows in America and Europe. He died in 1996.

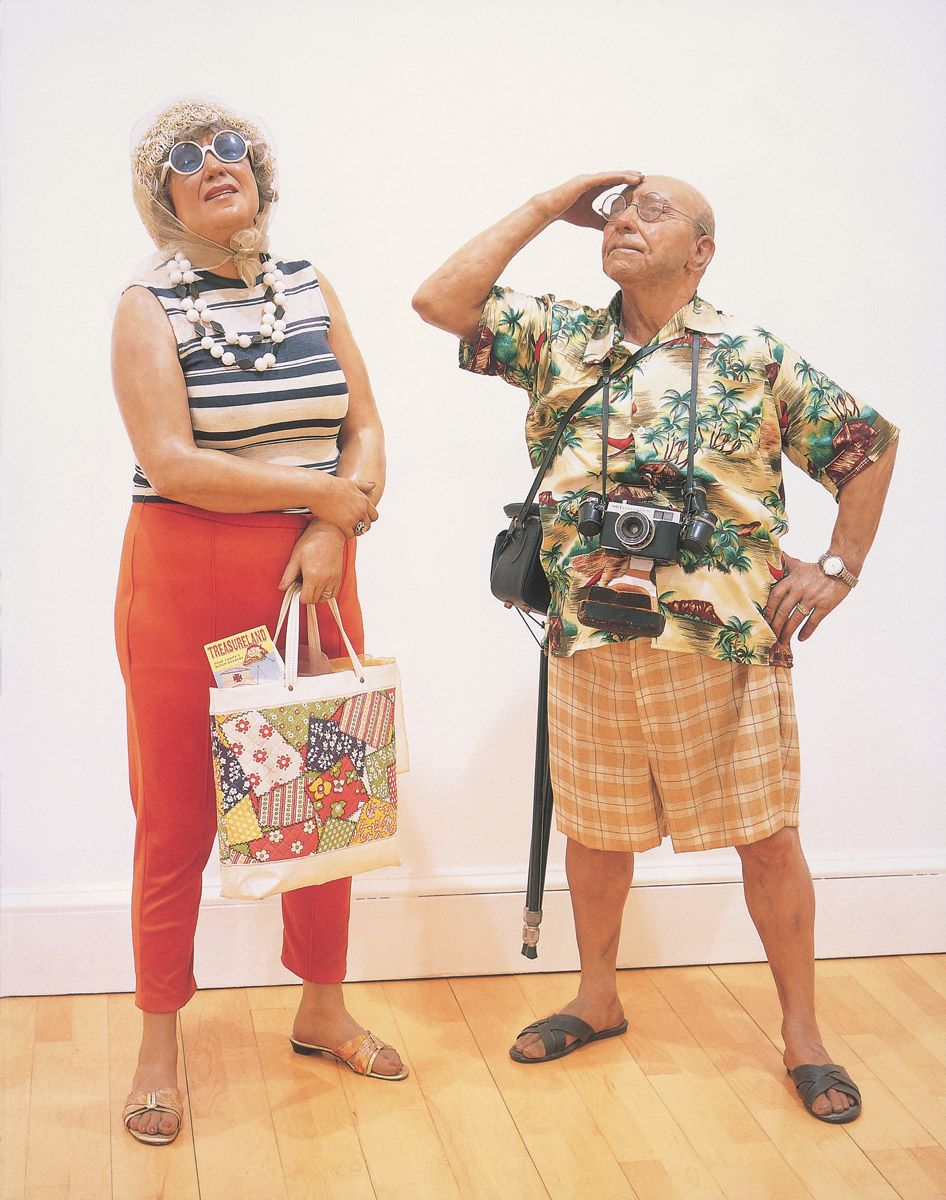

Hanson was a highly realistic sculptor, as this work demonstrates. What differentiates him from most equally representational sculptors, however, is that he never used his mature work simply to replicate appearances; instead, he employed it to isolate particular social types, such as the supermarket shopper (as here), the gawping tourist, the slovenly housewife, the down-and-out, the drug addict, the bank guard, the litterbug photographer and so on. Usually the sculptures are life-sized and always they were cast from life, with Hanson looking out for models whose physiognomies and build would best stand for the social types he wished to personify. To that end he would make plaster casts from his model, from which he would form moulds to be used to create the final works in various kinds of fibreglass. These sculptures would then be airbrushed, painted, have hair and other details added, and finally be clothed in real garments and shoes according to type.

We have all surely seen this type of slatternly, overweight woman trudging around a supermarket. By holding up such an accurate mirror to reality, Hanson forces us to a renewed awareness of the values such people represent.

Duane Hanson, Tourists, 1970. Polyester and fibreglass, polychromed in oil, with clothing and accessories, man 152 cm high, woman 160 cm high (life-size). Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh. Art © 2006 Estate of Duane Hanson/ Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

The irony of this work arises from the fact that the tourists are apparently peering at something worth looking at but are entirely oblivious to the fact that they themselves are a sight for sore eyes. As ever, Hanson’s alertness to the nuances of social behaviour and dress is caustic and exact.

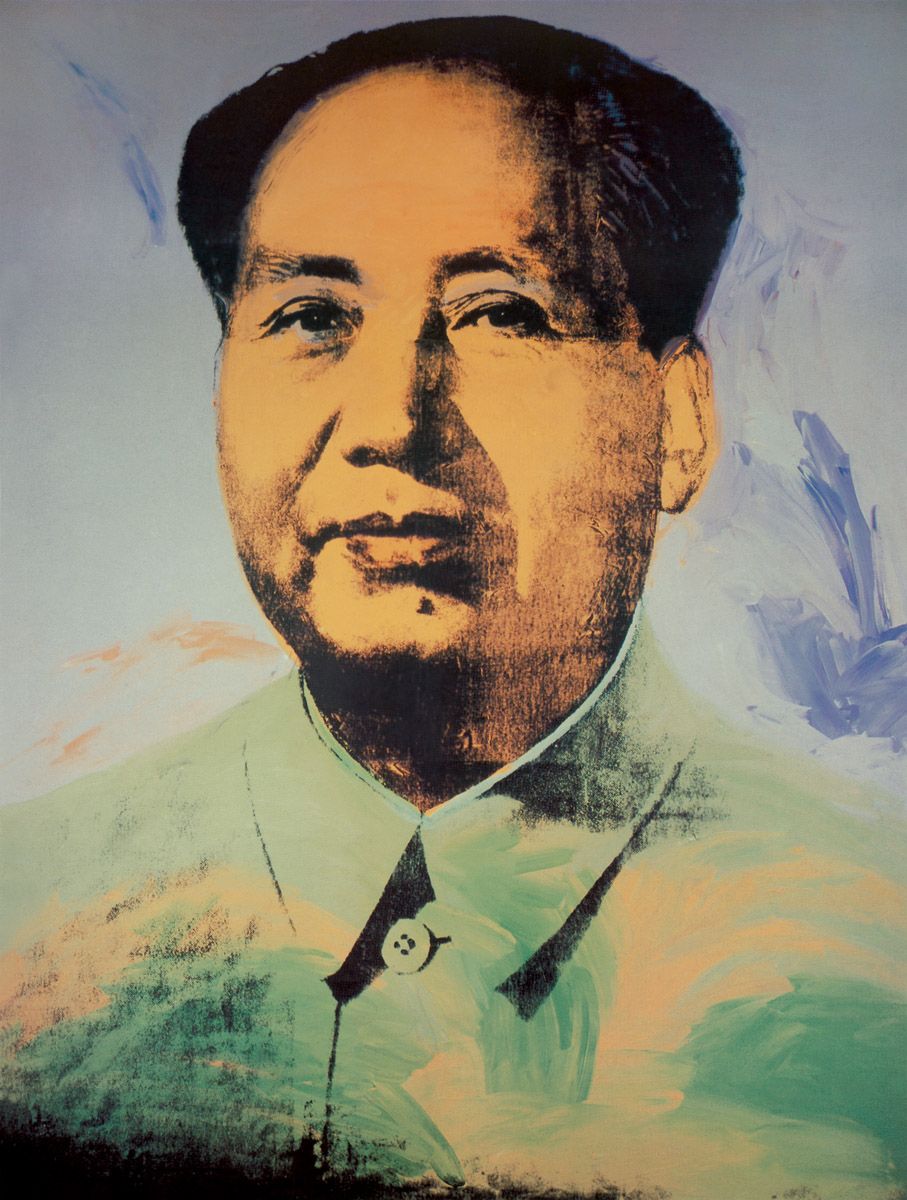

Andy Warhol, Chairman Mao, 1972. Silkscreen ink on synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 448.3 x 346 cm. Saatchi collection, London.

With the odd exception, between about 1961 and 1966 Warhol went out of his way to obtain the maximum degree of surface flatness in his paintings. To that end, the flattening inherent to silkscreen printing aided him enormously, although the pictures he made using the technique retain a certain vibrancy because of the grainy tooth of the canvas upon which the images were deployed. Such flatness may be seen as Warhol’s way of achieving the maximum degree of impersonality in his works, a detachment that stands in extreme contrast to the emotionalism often expressed through thickly-worked paint by the Abstract Expressionists. But by the end of the 1960s Warhol also began to use paint more thickly and expressively before he finally overprinted a photo-silkscreened portrait, as here. Probably this painterliness was his way of reinvesting the act of painting with some validity, for of course the major physical and sensory (not to mention sensual) difference between painting and photography resides in such a tactile emphasis.

As already noted, in his Chairman Mao series Warhol appropriated a communist holy icon and, with rich irony, then sold such images to western capitalist art lovers. In this particular painting the use of yellow for the underpainted flesh tones may have been intended to augment that irony by inducing associations of the ‘yellow menace’, an abusive term applied to Chinese communists by the American media during the Cold War, especially at the time of the Korean conflict in the early-1950s.

By working on a vast, billboard scale Warhol augmented the cultural associations of the image, for politicians customarily employ billboards to convince us of their virtues. Chairman Mao Zedong (as he is known today) was certainly no exception in that respect.

Richard Estes, Diner, 1971. Oil on canvas, 101.9 x 127 cm. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.

The stainless steel and glass diner with its clean lines and Art Deco curves is an American institution, and unsurprisingly a number of photorealist painters took these stylish, affordable and classless eating houses as their subject-matter. Here Estes paid homage to the Empire Diner which still stands on the corner of 10th Avenue and West 22nd Street in Manhattan. The row of telephone booths was introduced from elsewhere, thereby indirectly making it clear that photorealist painters can be just as selective regarding the formation of their images as are any other types of artist – they do not merely paint what they see (or even what their cameras see).

By making the diner and the line of telephone booths run right across the canvas in parallel with its top and bottom edges, and by omitting any figures, Estes strengthened the inherent formal values of the image. All the textures of the buildings, structures and pavements are lovingly explored, especially the reflectivity of metal. Against the fairly low-keyed greys, buffs, greens and blues spread across the picture, the red lines of the roof really stand out brilliantly.

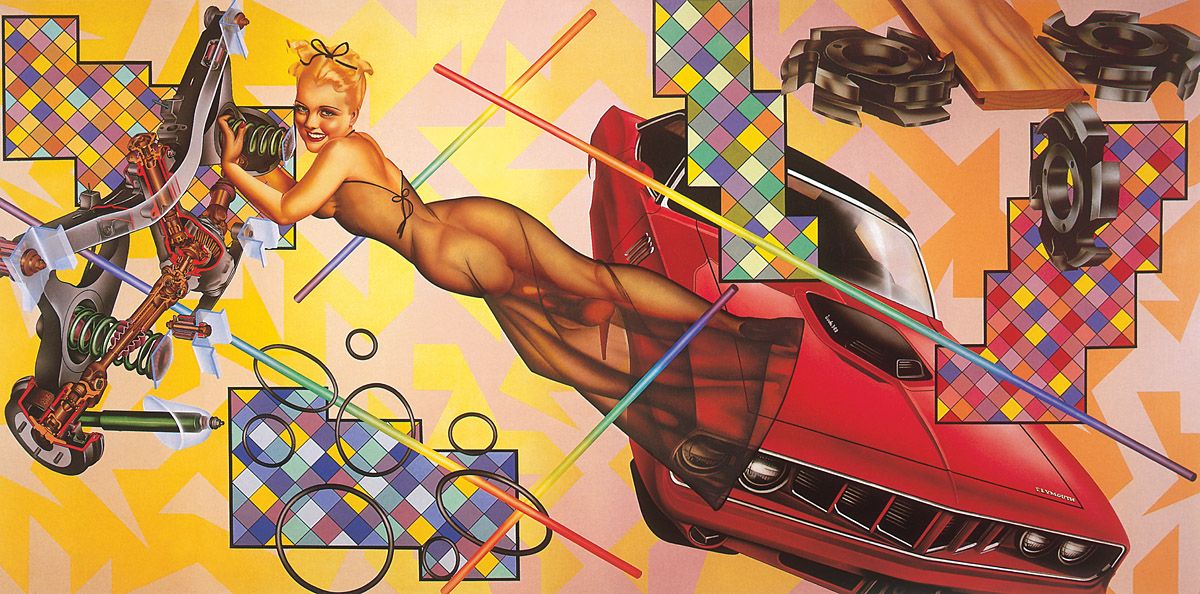

Peter Phillips, Art-O-Matic Cudacutie, 1972. Acrylic on canvas, 200 x 400 cm. Galerie Neuendorf, Frankfurt.

After Phillips moved to New York in 1964 he drew further upon the mass-communications imagery of machines, technological patterning and soft-core sexuality, developing highly complex visual statements about style and glamour, as here. He also began adding a more impersonal quality to his surfaces by employing one of the favourite tools of the advertising artist and photographic retoucher, the airbrush, which permits the perfect modulation of one colour into another. The results are resplendent, virtuosic images that openly revel in the banality of consumer culture.

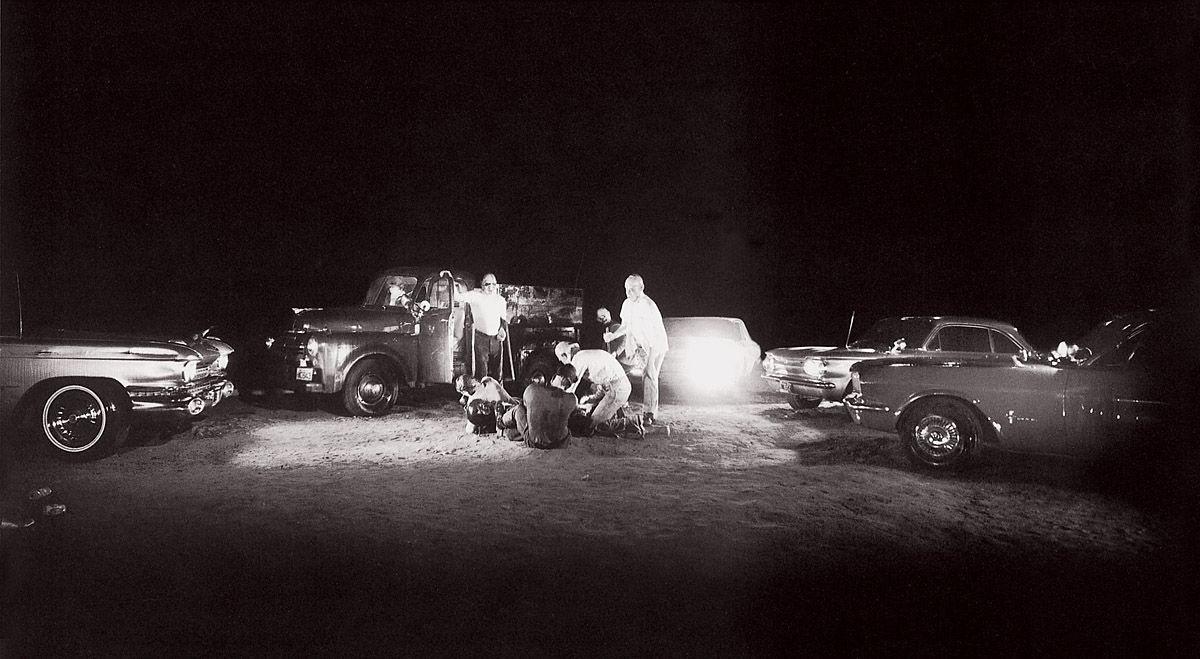

Ed Kienholz, Five Car Stud, 1969-72. Four cars and a pick-up truck, plaster casts, guns, rope, masks, chainsaw, clothing, oil pan with water and plastic letters, paint, polyester resin, Styrofoam rocks and dirt, various dimensions. Kawamura Memorial Museum of Art, Sakura, Japan.

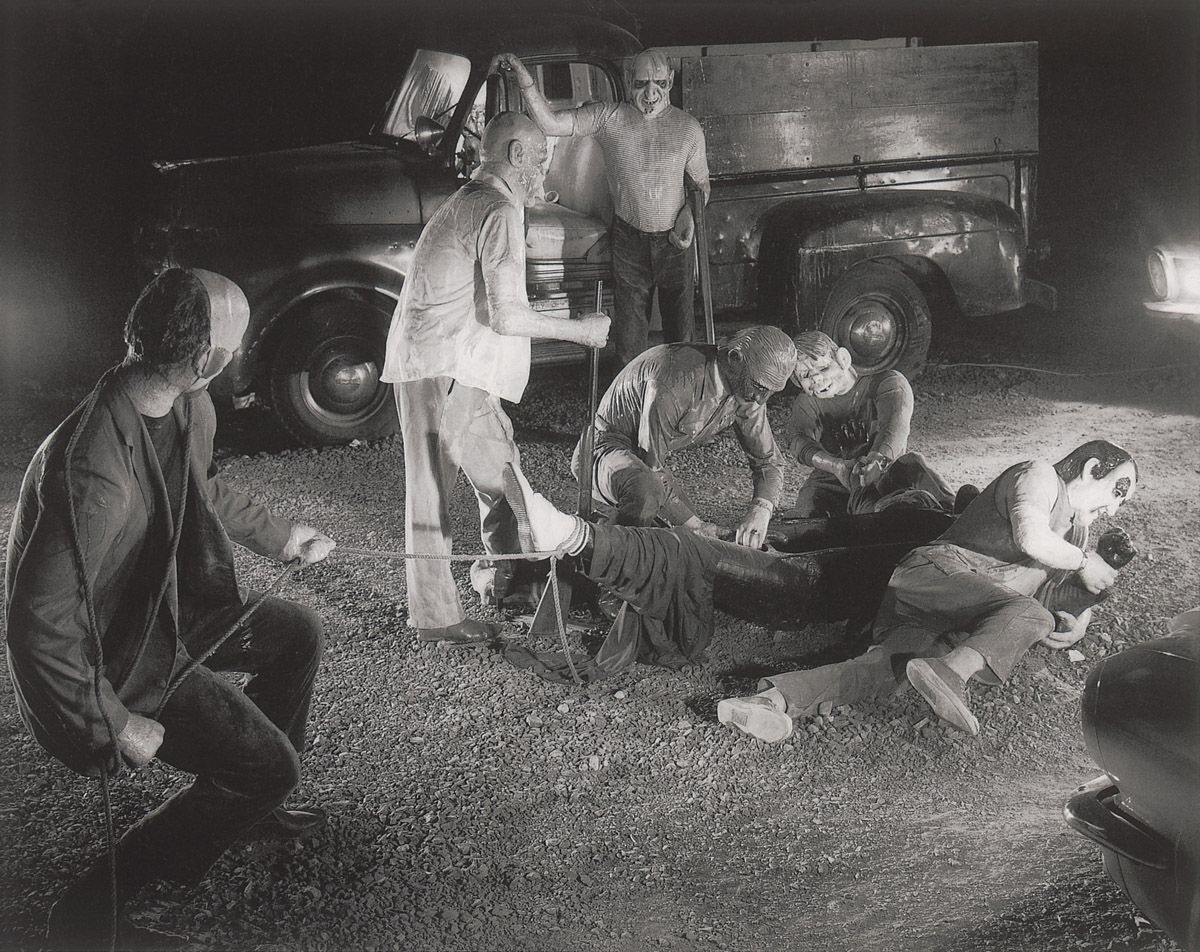

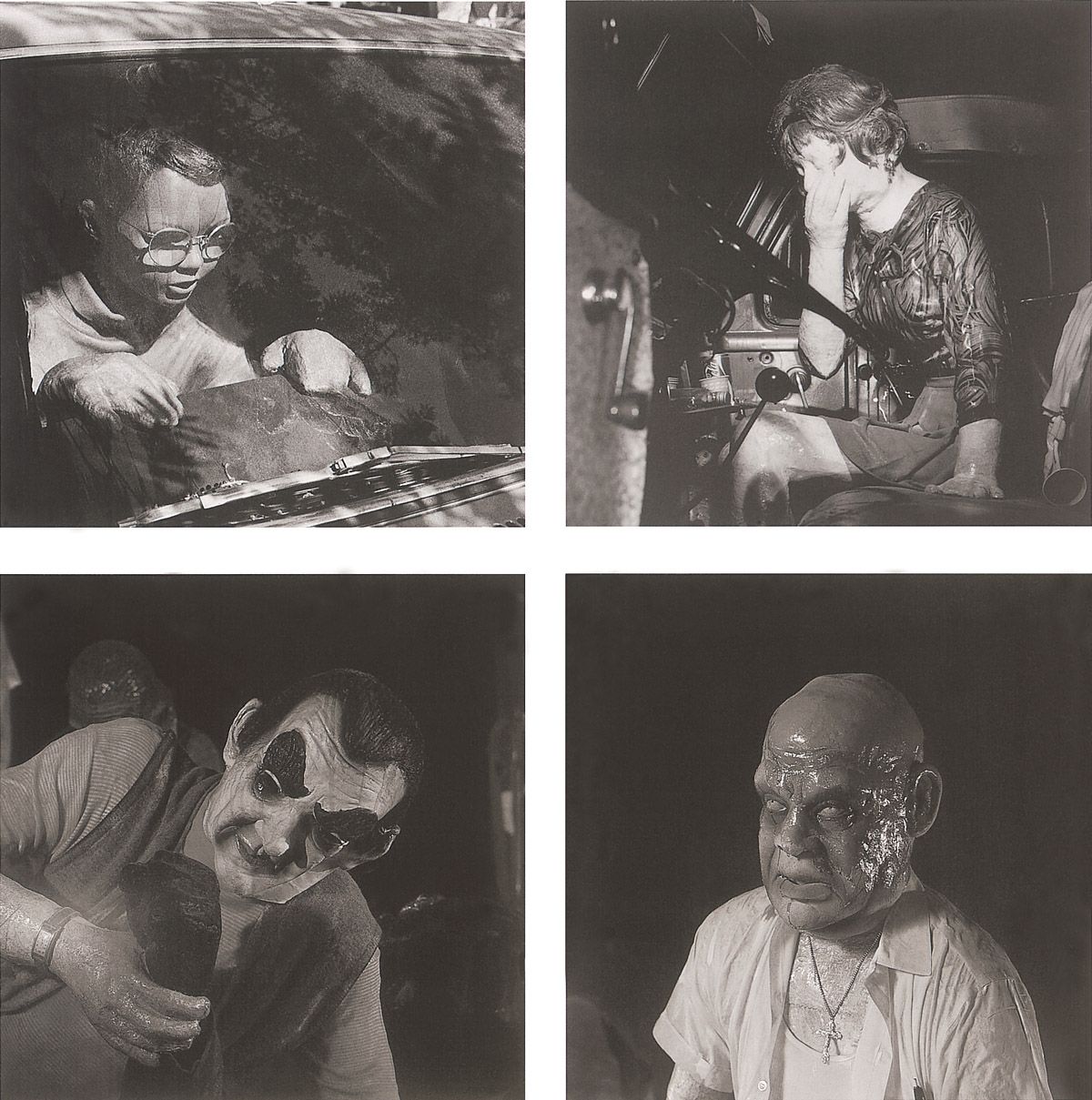

Here we witness the castration of an American black by white supremacists, all of whom are sporting grotesque Halloween face-masks to disguise their identities. Four of the assailants pinion the poor victim by holding down his arms or by standing on one leg as his other leg is pulled aside with a length of rope; another thug performs the castration. A sixth, shotgun-toting racist eggs on the others, while the man standing on the foot of the victim holds a further gun. We can infer he is a true Christian from the fact that he wears a crucifix around his neck. In the pick-up truck a white girl is vomiting; it remains unclear if she was the companion of the black youth or is simply throwing up because of what takes place before her. In one of the cars a bespectacled boy gazes intently at the scene; presumably he is the son of one of the attackers. All the vehicles were made in America, and each of the cars carries a license plate bearing the inscription ‘State of Brotherhood’.

The victim has two heads, one inside the other. The inner head originally topped a United States Army display mannequin and looks impassive; the outer, plexiglass head made by Kienholz is understandably screaming. A large automotive oil pan doubles as the victim’s torso and is filled with black water which suggests blood. On the surface of the liquid two sets of plastic letters gently bobble. One of them says ‘NIG’, the other ‘GER’, and occasionally they come together to form the entire racist epithet (to which connective end a submerged pump stirs up the water).

Given the many racist attacks by whites on blacks that have taken place in America since 1972, this sculpture has lost none of its relevance. As Kienholz said of it, “I think of that piece in terms of social castration…like what a tragedy [it is] we didn’t use the richness of America, which includes the black.”

Four cars and a pick-up truck, plaster casts, guns, rope, masks, chainsaw, clothing, oil pan with water and plastic letters, paint, polyester resin, Styrofoam rocks and dirt, various dimensions. Kawamura Memorial Museum of Art, Sakura, Japan.

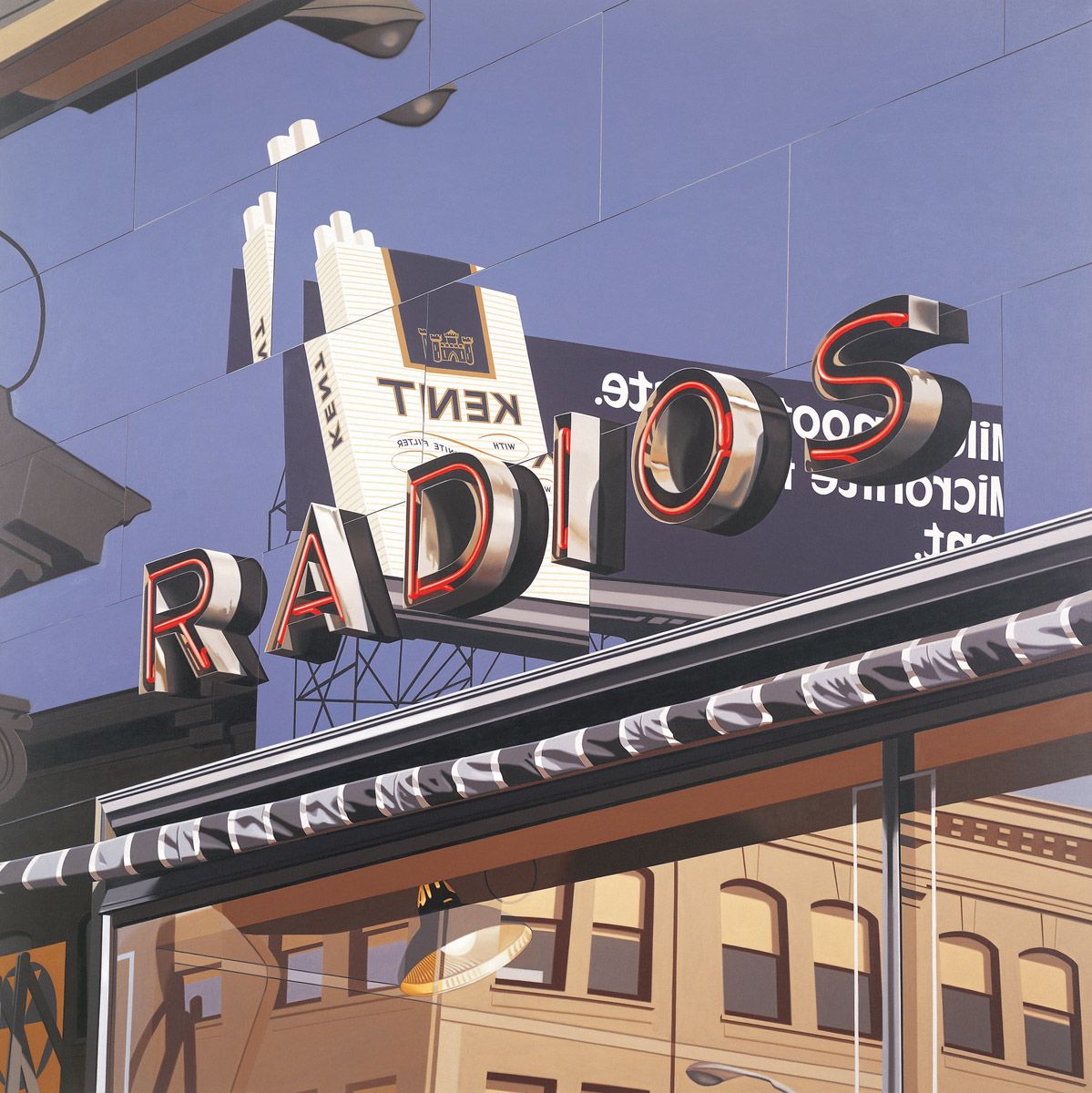

Robert Cottingham, Radios, 1977. Oil on canvas, 198 x 198 cm. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

Robert Cottingham was born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1935. He studied between 1959 and 1963 at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. His first one-man show was held at the Molly Barnes Gallery in Los Angeles in 1968. Subsequently he has exhibited all over the world.

Cottingham principally painted trucks in the mid-1960s, before turning his attention to houses, which he entirely divorced from their skies and backgrounds. During the 1970s he increasingly turned his attention to shop fronts and the upper parts of buildings, with their plethora of signs. Such narrow sections of edifice had always appealed to him, not only because their formal patterns and colouristic riches allowed him to bring out the purely abstractive qualities of things but also because they permitted him to capture many of the key symbols of American consumerism. Thus in the present work it is easy to appreciate Cottingham’s responsiveness to the unusual and rather marvellous shapes made by the reflected and fragmented Kent cigarette hoarding, as well as to the interplay between those forms and the inherent shapes of the shop’s upper part. Similarly, the reflections of buildings upon the plate glass window interact with the lines of the glass and the spotlight inside the store. Everywhere spatial ambiguity increases the pictorial interest and variety, and of course Cottingham is highly responsive to the confusion of the urban environment, from which he extracts both clarity and beauty.

Patrick Caulfield was born in London in 1936. He studied at Chelsea School of Art between 1956 and 1960, and then at the Royal College of Art between 1960 and 1963. His initial one-man exhibition was held at the Robert Fraser Gallery in London in 1965, and he first showed in New York the following year. Many exhibitions followed globally. Retrospectives of Caulfield’s prints were mounted in 1973, 1977, 1980 and 1981, in which year a large retrospective of his paintings was held in Liverpool and London. He died in 2005.

Caulfield was another painter within the Pop/Mass-Culture Art tradition who consistently amplified the vulgarity of things. By flattening and simplifying his forms, and by frequently taking his subject-matter from the most ordinary of interiors such as hotel lobbies, dining rooms, restaurants, bars, cafés and offices, as well as domestic spaces containing retro or just badly designed furniture, he transformed what was already banal into a subtle form of kitsch. In later years he indulged his penchant for painting still-lifes of food, ceramics, flowers, wine glasses, desk lights, lanterns, pipes and the like, often pushing the images to the verge of abstraction.

In the present painting Caulfield explored the contrast between two types of imagery: his customary flattened and simplified forms, and photographic realism, with all its detailing and complex naturalistic colours. The waiter lolls on a support, presumably tired from his lunchtime exertions. The intensity of the overall mauve colouring is sharpened by the contrasting colours of the landscape mural, fish tank and goldfish.

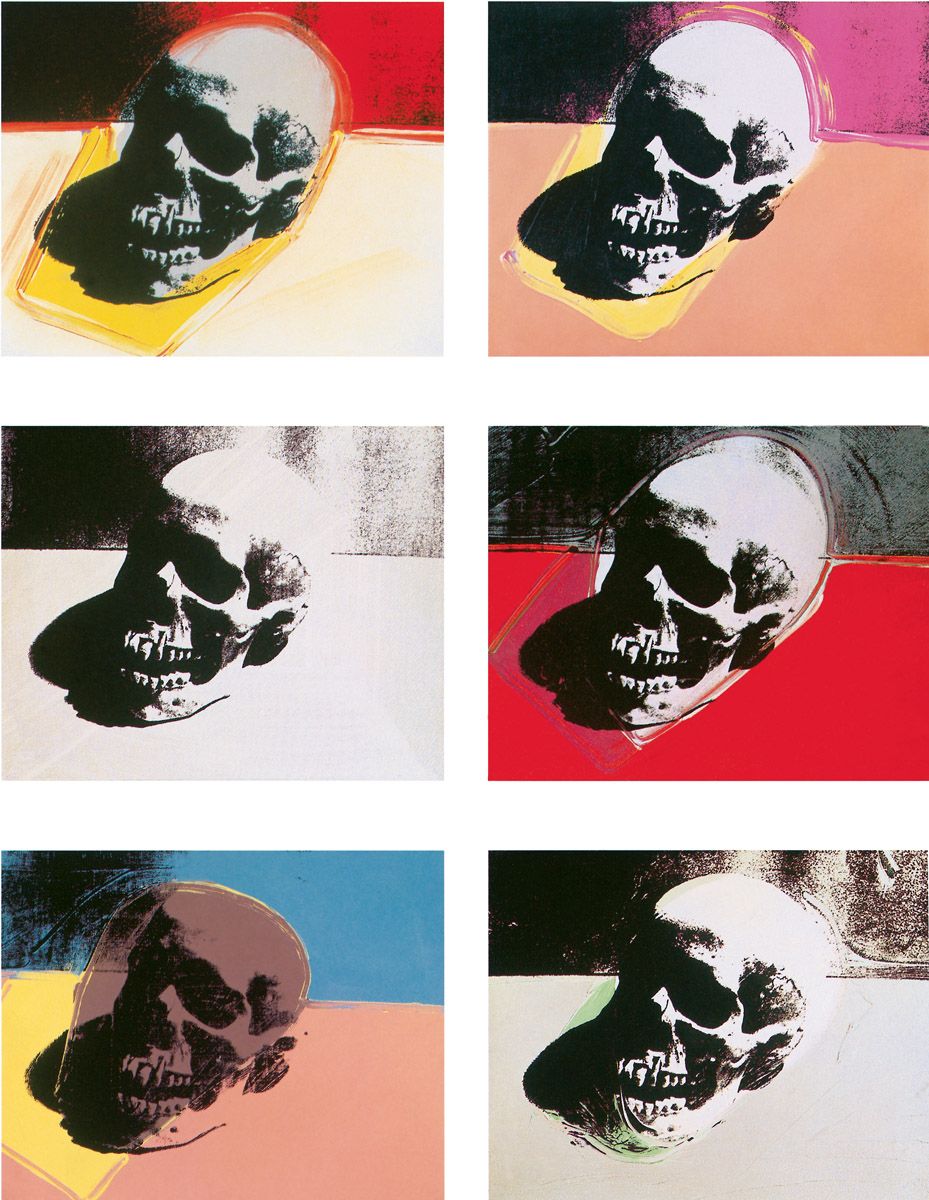

Andy Warhol, Skulls, 1976. Silkscreen ink on synthetic polymer paint on canvas, each 38.1 x 48.3 cm. The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc., New York.

Despite Warhol’s customary declaration that there are no meanings behind the surfaces of his works, the Skulls series demonstrates his underlying seriousness of purpose. The images were made from photographs of a skull he had bought in a Paris flea market around 1975. He was encouraged to develop the series by his business manager, Fred Hughes, who reminded him that artists such as Zurbarán and Picasso had painted skulls to great expressive effect. Moreover, Warhol’s studio assistant, Ronnie Cutrone (who became his professional helper in 1974), also encouraged him to portray skulls by remarking that it would be “like doing the portrait of everybody in the world”.

At Warhol’s behest, Cutrone took a great many monochrome photographs of the skull from a number of different angles. He lit it harshly and from the side so as to obtain the most dramatic visual effects through maximising the light and dark contrasts, as well as enhancing the shadows cast. In most of the Skulls images (such as the ones seen here), the use of vivid colours tends to glamorise the object. That glamorisation is highly ironic, given the way that the leering skull points up the superficiality of glamour: in the midst of life we are in death indeed, as Andy Warhol the media Superstar was only too painfully aware after he had been shot by a demented follower in 1968.

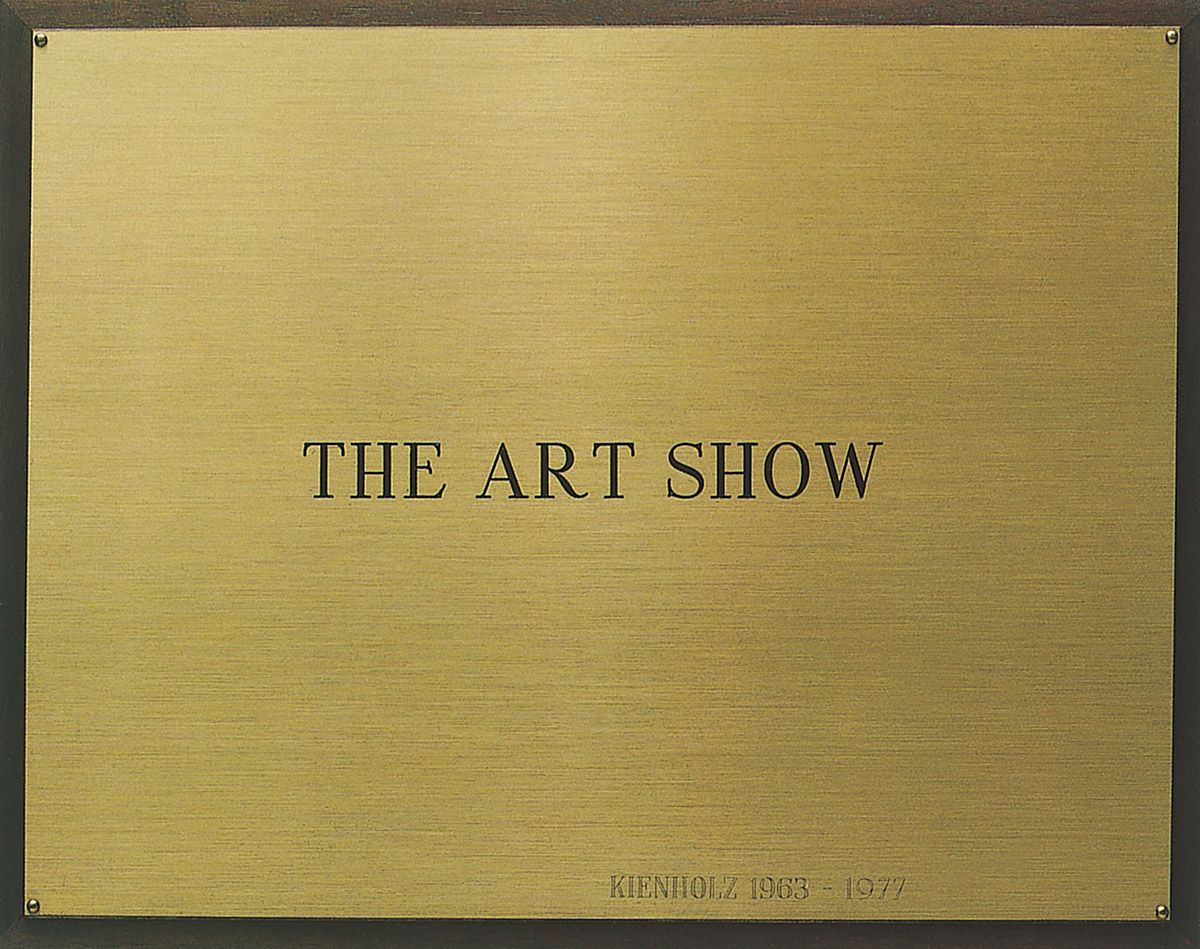

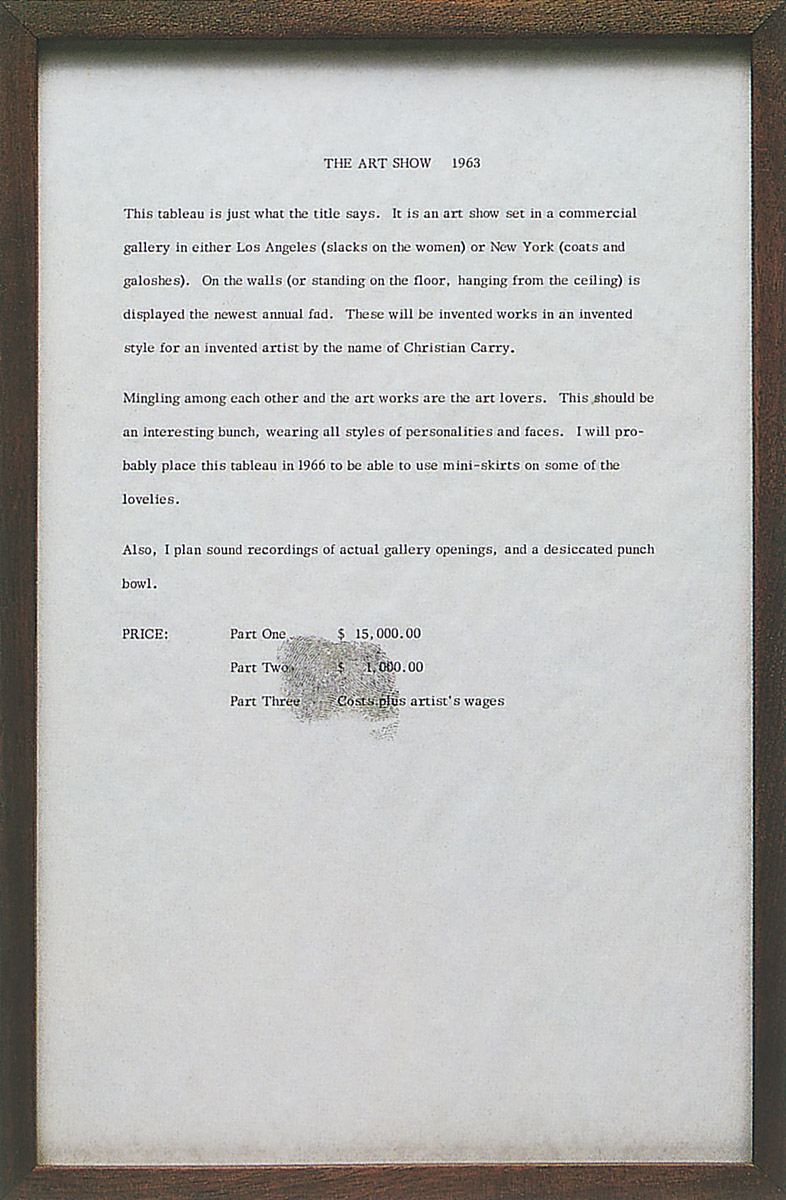

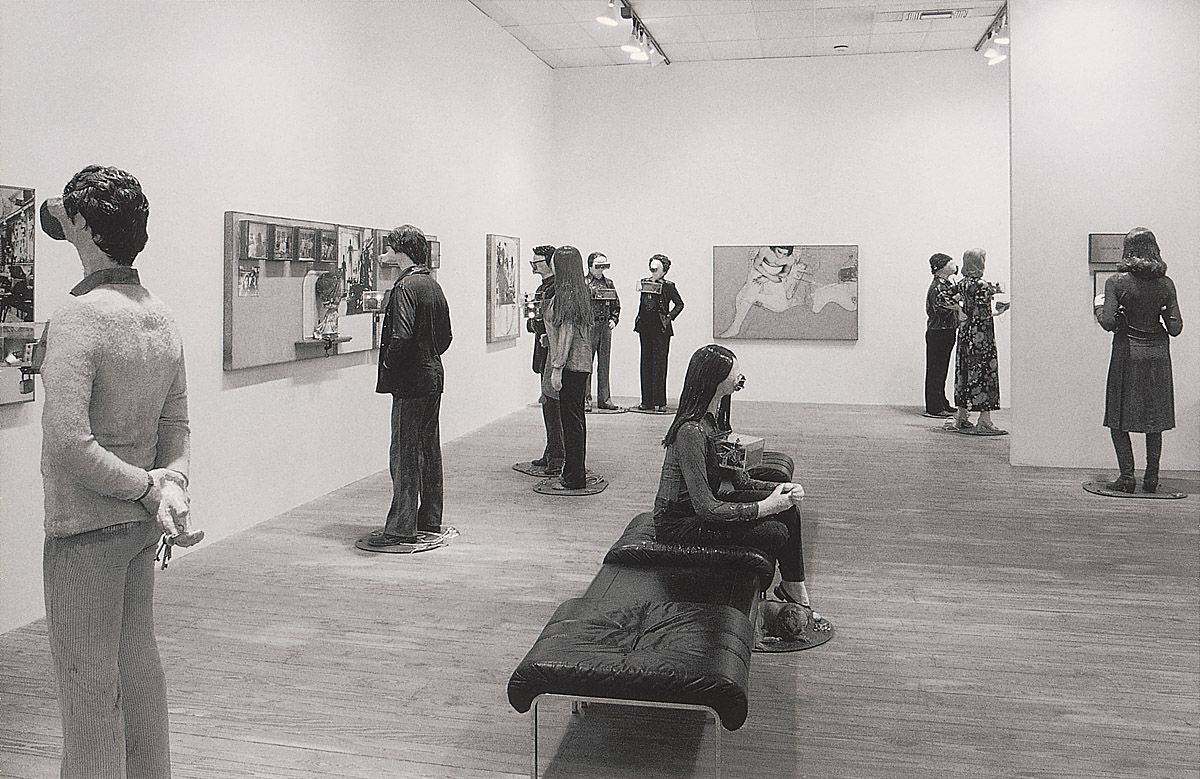

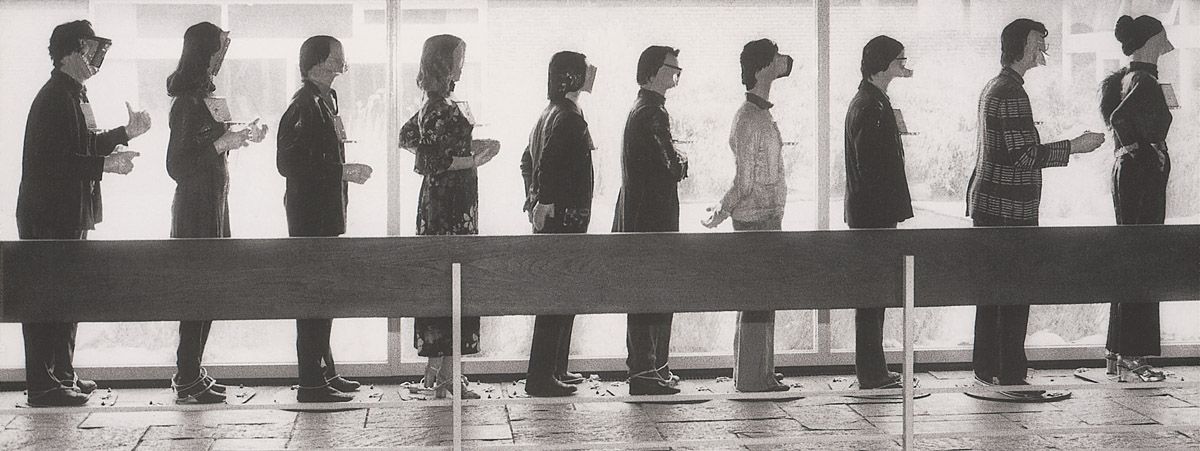

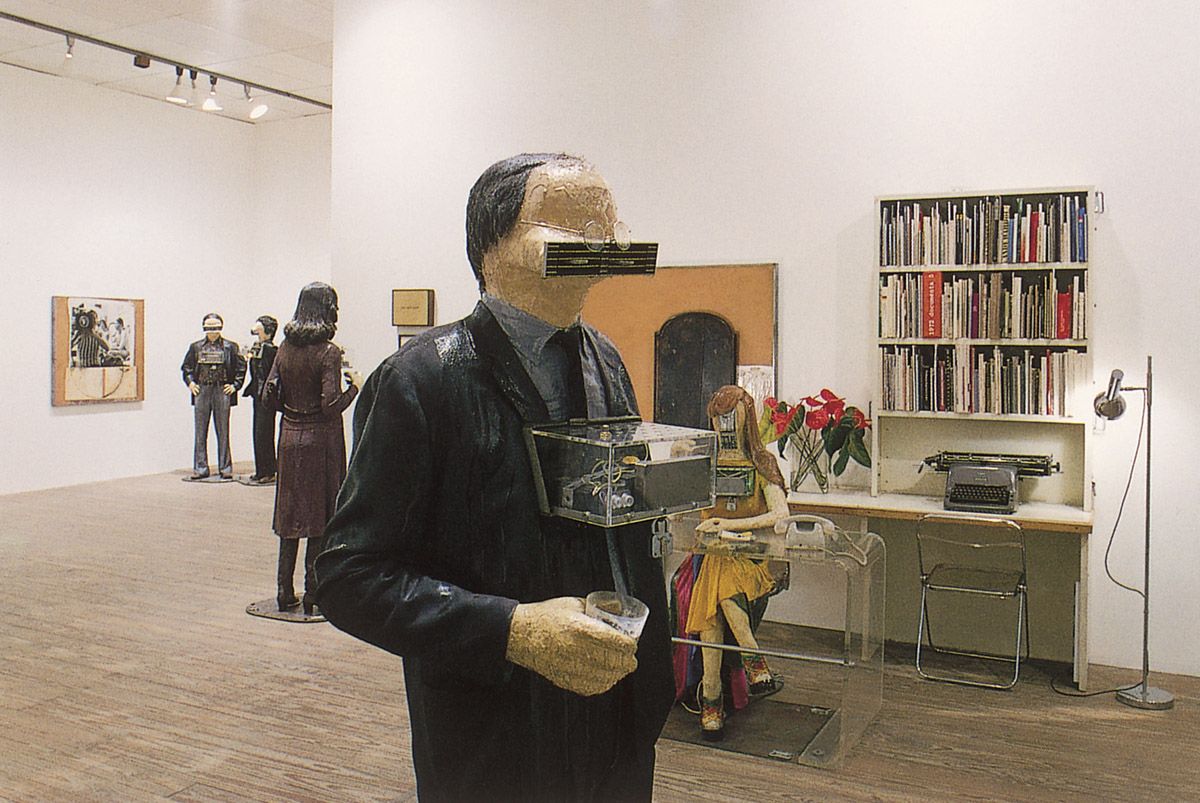

Ed Kienholz and Nancy Reddin Kienholz, The Art Show, 1963-77. Plaster casts, clothing, plexiglass boxes, recorded sound, audio speakers, automobile air-conditioning vents and fans, furniture, wall sculptures, paintings, drawings, books, punch bowl, glasses and tablecloth, dimensions variable. Courtesy L.A. Louver Gallery, Venice, California.

Although Kienholz first conceived this work in 1963, it was not until he met Nancy Reddin in 1972 that the project began to materialise. Following the completion of the work four years later, it was exhibited at the Pompidou Centre in Paris in 1977, after which it was shown in Düsseldorf, Munich, Berlin, the Louisiana Museum in Humblebaek (Denmark), Dublin, San Francisco and Houston. It was also included in the vast Kienholz retrospective that toured New York, Los Angeles and Berlin in 1996-7.

The Art Show comprises nineteen men and women plus a dog, and all the figures were modelled upon people known to Kienholz and his wife; they include the sculptor Eduardo Paolozzi, the collectors Monte and Betty Factor, and the art curator and one-time director of the Pompidou Centre, Pontus Hulten. As with the people who are represented in The Beanery of 1965 and later sculptures, plaster bandages formed the basis for the moulds from which the figures were cast. Every one of those people is dressed in real clothing, over which fibreglass resin was brushed to unify the works visually. Parts of the figures were also painted. Kienholz and Reddin made fourteen collages in order to develop this ensemble, and they are displayed on the gallery walls. To one side a receptionist is seated at a desk, with a typewriter, floorlight and bookcase filled with art books and catalogues behind her. Some of the people represented hold wine glasses, which tells us we are witnessing a gallery opening rather than an ordinary moment during the life of an exhibition. The guests wear the type of smart but casual attire usually seen at such soirées. Naturally, the physical relationship of the figures, pictures and furniture varies according to the space in which the work is exhibited.

Amid their faces all of the people sport automobile air-conditioning vents which Kienholz originally retrieved from a Los Angeles scrap yard. Internal motors and fans blow forth hot air that parallels the metaphorical hot air often spoken at art world functions. Within the heads are audio speakers connected to a tape recorder mounted on the chest of each figure, and they constantly supply a typically vacuous background babble of pretentious art-world remarks – what Kienholz described as “all that art world twaddle that critics write, which doesn’t have much meaning and [which] no one understands or gives a damn about anyway.” The model for one of the figures was a Russian girl who supplied her dialogue in her native tongue, on the basis that “The art reviews from [Russia] are just as stupid as from anywhere else.” For his contribution Paolozzi drew up a series of questions and answers which he read in a wholly random and disconnected order, thus making ‘the usual kind of critical sense’. The Art Show might not afford the most profound of insights but it certainly captures the shallowness of an age in which art, money, power and pretentiousness have all become more intermingled than ever.

Ed Kienholz and Nancy Reddin Kienholz, The Art Show, 1963-77. Plaster casts, clothing, plexiglass boxes, recorded sound, audio speakers, automobile air-conditioning vents and fans, furniture, wall sculptures, paintings, drawings, books, punch bowl, glasses and tablecloth, variable dimensions. Courtesy L.A. Louver Gallery, Venice, California.

Wolf Vostell, Television Obelisk – Endogenous Depression (Homage to Gala-Dalí and Figueres), 1978. 15 televisions coated in mortar diluted with pink cement, with bust and television antenna, 13 metres high. Theatre Museum Dalí, Figueres, Catalonia, Spain.

Wolf Vostell was born in Leverkusen, Germany in 1932. He first learned photolithography and in 1954-5 studied painting and typography in Wuppertal. In 1955-6 he attended the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where he studied painting, anatomy and graphics. At the Düsseldorf Academy in 1956-7 he also studied art while simultaneously exploring the Talmud and the paintings of Hieronymus Bosch. By now his work was in the forefront of contemporary artistic experimentation, and from 1958 onwards he organised the Décollage tearing-down of posters, images he further defaced by overpainting. He also began participating in Happenings and in 1962 was one of the founders of the FLUXUS group. This was dedicated to live expression and violently opposed to tradition. Between 1963 and 1965 Vostell held several solo exhibitions in New York. In 1966 one of his Happenings, Dogs and Chinese not allowed, was created over a period of two weeks throughout the New York subway system. Later activity involved the setting of cars in concrete; the making of films; and the creation of a mobile museum, in the form of a ‘FLUXUS train’ which toured north-west Germany. Exhibitions and retrospectives of his work were held in Cologne in 1966; in Nuremberg and Venice in 1968; in Paris in 1974; in Berlin in 1975; and at three museums in Spain in 1978-9. In 1976 Vostell founded his own museum in Malpartida, near Cáceres in Spain. He died in 1998.

What connected Vostell with mass-culture was television, for in 1958 he was the very first artist to incorporate working TV sets into assemblages and paintings. The apparatuses would remain integral to his output thereafter, as would cars and even jet airplanes and missiles. Occasionally he would combine televisions with cars, as happened in 1981 when he adorned a Mercedes limousine with 21 television sets linked to a camera, and in 1991 when he created his Auto-TV-Wedding. This comprised the smashed wreckage of a Mercedes sedan covered in television sets and wine glasses. The work was eerily prescient of the death of Diana, Princess of Wales, just six years later.

In September 1978 Vostell, Salvador Dalí and the mayor of Malpartida met at the Dalí museum in Figueres and contracted that both artists would exchange works for their respective museums. For the Malpartida museum Dalí authorised Vostell to realise his idea for a ‘Backdrop to Parsifal’, while Vostell made this work for the courtyard of the Figueres museum. Structurally it comprises two concrete posts, with the televisions supported by iron crossbeams. Five of the televisions actually work, and they also double as video monitors. By calling the work ‘Obelisk’, and by topping the piece with a classical-looking bust (which supports a television antenna), Vostell brought into play associations of the memorial purposes of such ancient monoliths. Naturally, a tower made out of television sets also lends itself to contemporary memorialising, for daily we are bombarded with commemorations and the like over the airwaves.

The overall form of the Television Obelisk clearly derived from the 29.2 metre-high Column Without End of 1937-8 by the Romanian sculptor Constantin Brancusi. This too stands in the open air, in the small Romanian town of Tîrgu-Jiu, and is equally made up of 15 modules. Like that statement about an endless chain of being, Vostell’s work reminds us that television is apparently infinite. And the second part of his title furthers that message, for the word ‘endogenous’ means ‘growing from within’. Vostell’s titular related meaning is therefore clear: television spawns itself, spreading depression as it grows and grows and grows….

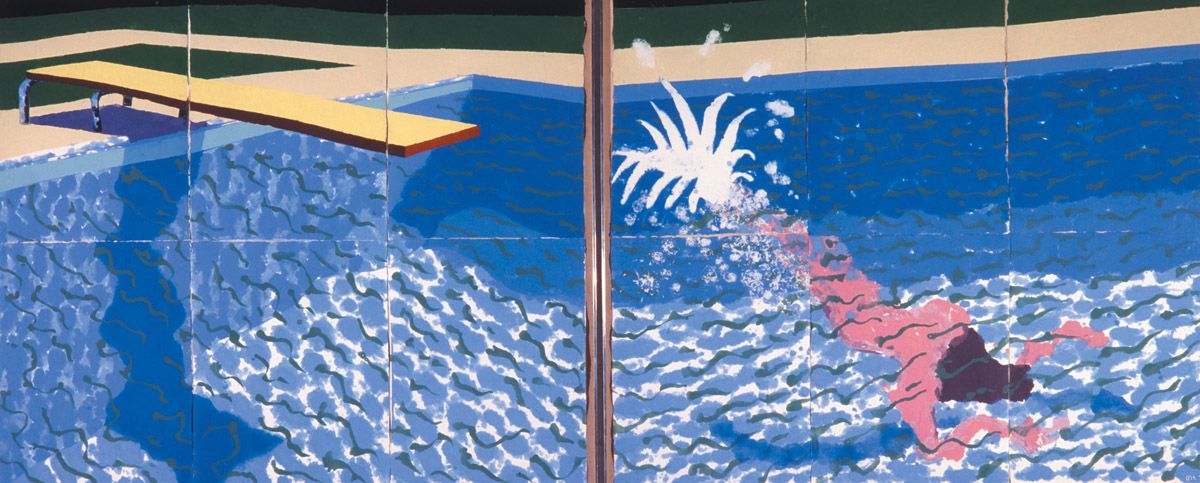

David Hockney, Le Plongeur (Paper Pool #18), 1978. Coloured pressed paper pulp, 182.9 x 434.3 cm. Bradford Art Galleries and Museums, West Yorkshire, England.

This work forms part of a series of twenty-nine prints made at Tyler Graphics near Mount Kisco in New York State between August and October 1978. Instead of colour being inked on to the surface of paper as is normally the case with prints, Ken Tyler had found a way of pressing pigment into the sheet while it was still in a pulpy state during the papermaking process, thereby effecting a total fusion between carrier and image. This technique appealed to Hockney, not least of all because it imparted enormous richness and depth to the colour. However, as it proved impossible to make the sheets of paper as large as the artist required, the images are composites of smaller sheets joined together. The pool depicted was the one owned by Ken Tyler near his workshop, and the model for the swimmer was David Hockney’s friend, Gregory Evans. Each image was developed from numerous drawings and Polaroid photos taken of the swimmer and pool. The set of prints marked Hockney’s final engagement with a subject he had explored very fruitfully since the mid-1960s, and thus with an aspect of hedonism that has proved enormously attractive in the age of mass-culture.

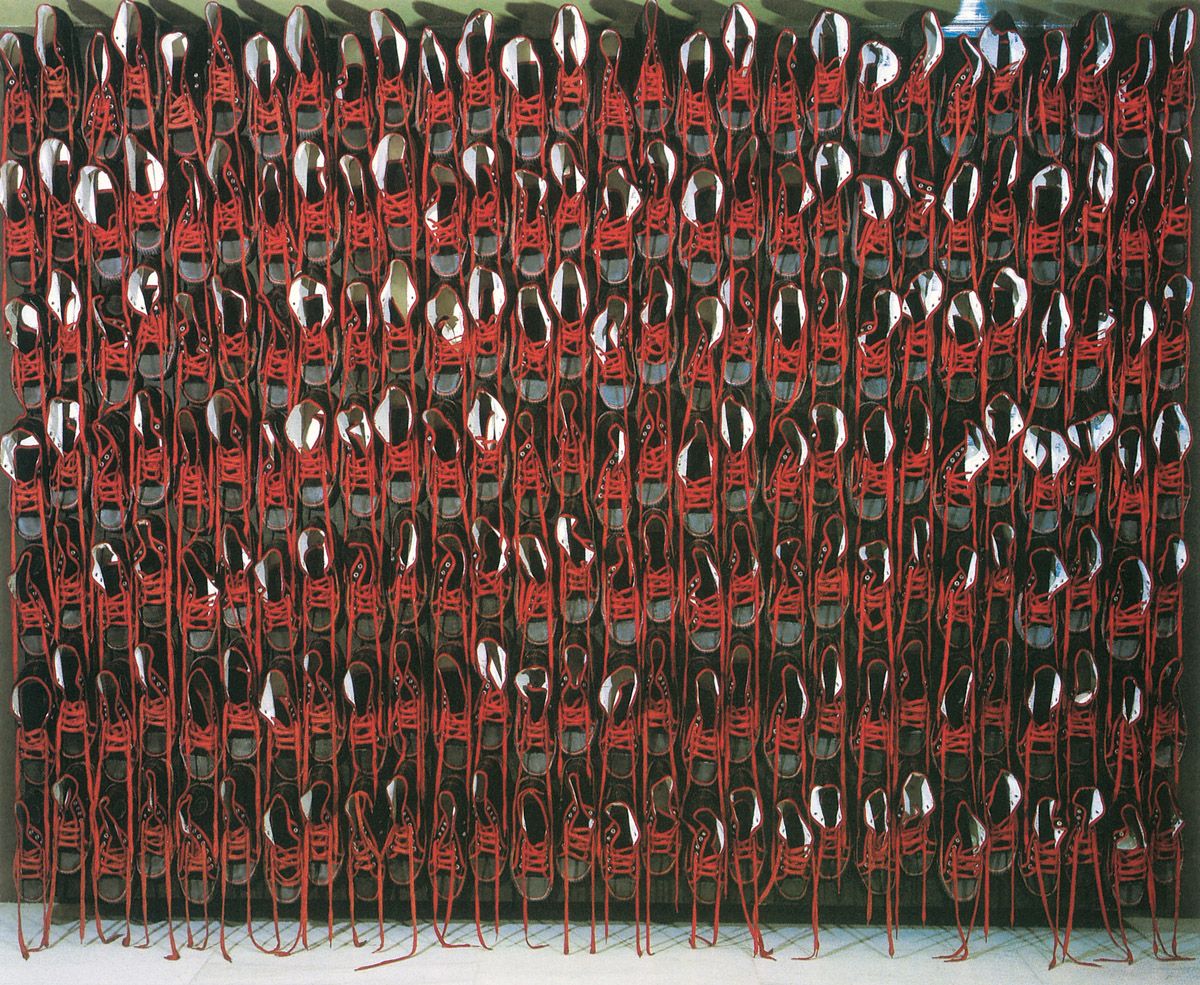

Arman, New York Marathon, 1978. Accumulation of basketball sneakers on wooden backing, 180 x 280 x 10 cm. Patrick Combes collection, Paris.

Here, and not for the first or last time either, Arman created a total congruence between subject and object, for what could more aptly allude to a gigantic assembly of people running through urban streets than this vast accumulation of sports shoes? Moreover, what could more generally represent the huge stacks of artefacts that stand at the heart of modern society?

The red laces are looped within the shoes and then hang down to form vertical lines not unlike the streams of paint in Arman’s Bonbons Anglais of 1966. The looping and fairly parallel lines could suggest marathon runners first milling around and then all following the same path.

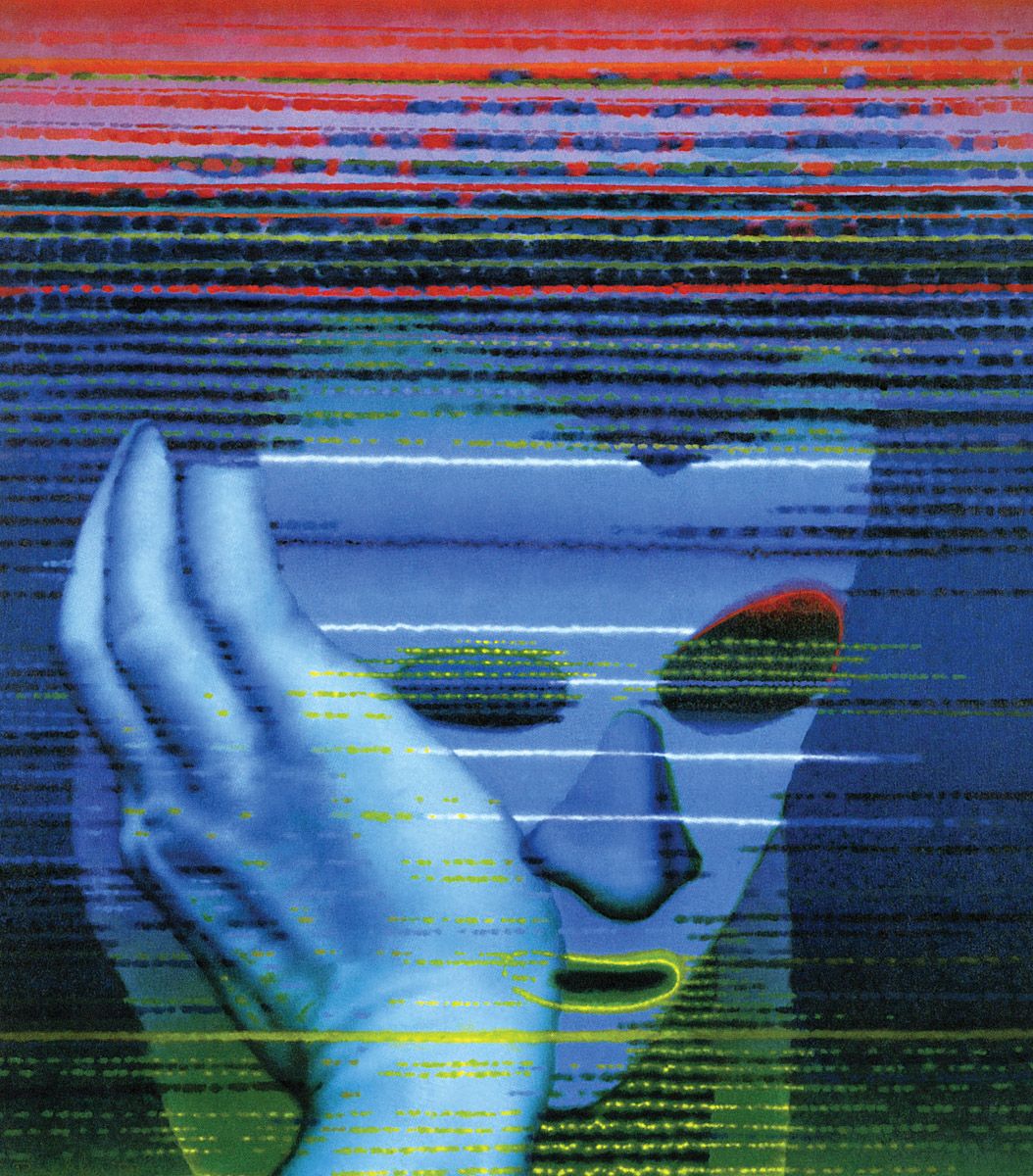

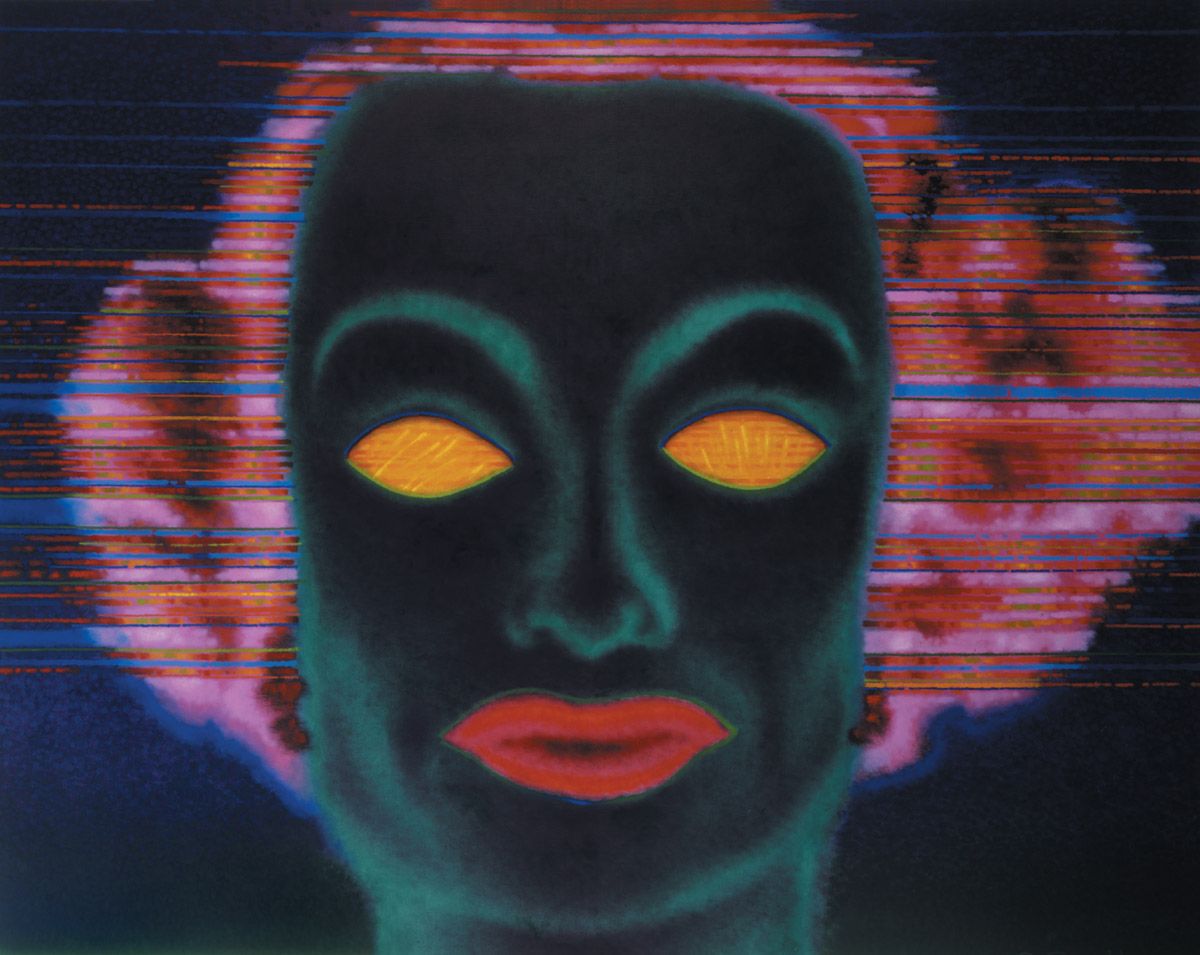

Ed Paschke, Strangulita, 1979. Oil on canvas, 116.8 x 203.2 cm. Collection of Martin Sklar, New York.

Ed Paschke was born in Chicago in 1939. Upon graduation from the Art Institute of Chicago in 1961 he was awarded a travelling fellowship, with which he toured Mexico. He received his Master’s degree from the same institution in 1970; between those two periods of study he was drafted into the army and then toured Europe; spent a period painting in New York; and worked as a commercial artist in Chicago to support his activities as a painter. He held his first solo show at the Deson-Zaks Gallery in Chicago in 1970. In that same year he was profoundly impressed by a large Warhol exhibition in Chicago. He also took the first of many higher-education teaching posts. His initial New York exhibition was mounted at the Hundred Acres Gallery in 1971 but received unfavourable reviews, a response that strengthened his resolve to stay in Chicago. Subsequent shows proved more successful and included an exhibition that toured Britain in 1973, as well as displays in Paris and Cincinnati the following year. Subsequently his work was seen many times in solo and collective exhibitions across the world. A retrospective was mounted at the Pompidou Centre, Paris, in 1989. Paschke died in 2004.

Until about 1977 Paschke painted curious, rather surrealistic images of musicians, circus performers, transvestites, weird-looking women, masked figures, the vertically-challenged, film stars and the like, occasionally with a violently threatening edge. However, in that year he also began to assimilate the influence of neon-lighting effects and the linear patterns typical of electronic communications and medical diagnostic machines. These phenomena can be seen here, along with a touch of the violence. The combination of imagery and overlaid lines suggests the victim has been successfully strangled, with the patterns taking a fairly even course, as though heartbeat, mental activity and other bodily functions are now ceasing.

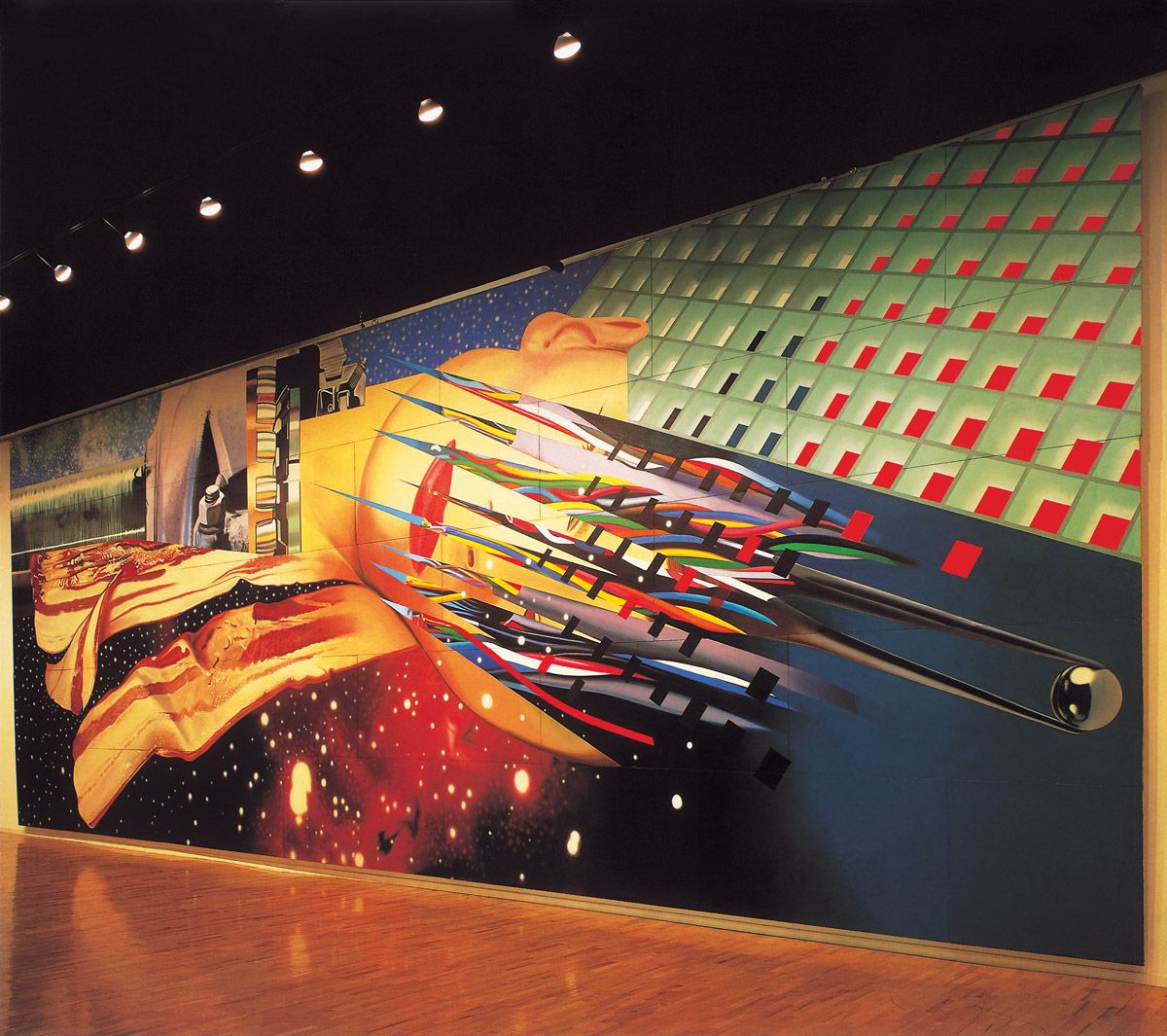

James Rosenquist, Star Thief, 1980. Oil on canvas, 518.2 x 1402.1 cm. Private collection, Museum Ludwig, Cologne. Art © 2006 James Rosenquist/ Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

In 1981 the retired astronaut and then-President of Eastern Airlines, Frank Borman, blocked the use of this painting in the new Miami air terminal (for which it had been commissioned). Perhaps that is unsurprising, for to untutored minds the image would appear to be composed of unconnected fragments of reality. These take the form of several rashers of bacon, a few pieces of machinery, some slivers of a glamorous female face as it might be seen in an advertisement, a tangle of electrical wiring, and a large-grid architectural structure, all set against an interstellar backdrop. However, only a little considered thought proves necessary to make sense of the work.

The painting is a brilliant metaphor for the earth passing through space. Instead of depicting it as a globe covered in land and water, Rosenquist has denoted it by means of some of the products and activities that typify aspects of human development: the animal husbandry and architecture by which we respectively feed and house ourselves; the mechanical and electronic inventions by which we make our lives more comfortable and communicative; and the presentational and selling imagery through which we might appeal to others and thus prosper. This vast reflection of human talents floats in space, stealing light from the stars.

Patrick Caulfield, Dining/Kitchen/Living, 1980. Acrylic on canvas, 180 x 180 cm. Tochigi Prefectural Museum of Fine Arts, Japan.

Caulfield’s responsiveness to patterning received full rein here, with a very jazzy feeling being imparted by the insistent wallpaper. As in the work by the same artist discussed above, here again he made a somewhat vulgar interior look far more banal by painting it in such a detached manner. And once more we see the placing of a small area of intense realism within a more abstractive surround, in order to intensify the visual impact of opposed types of imagery.

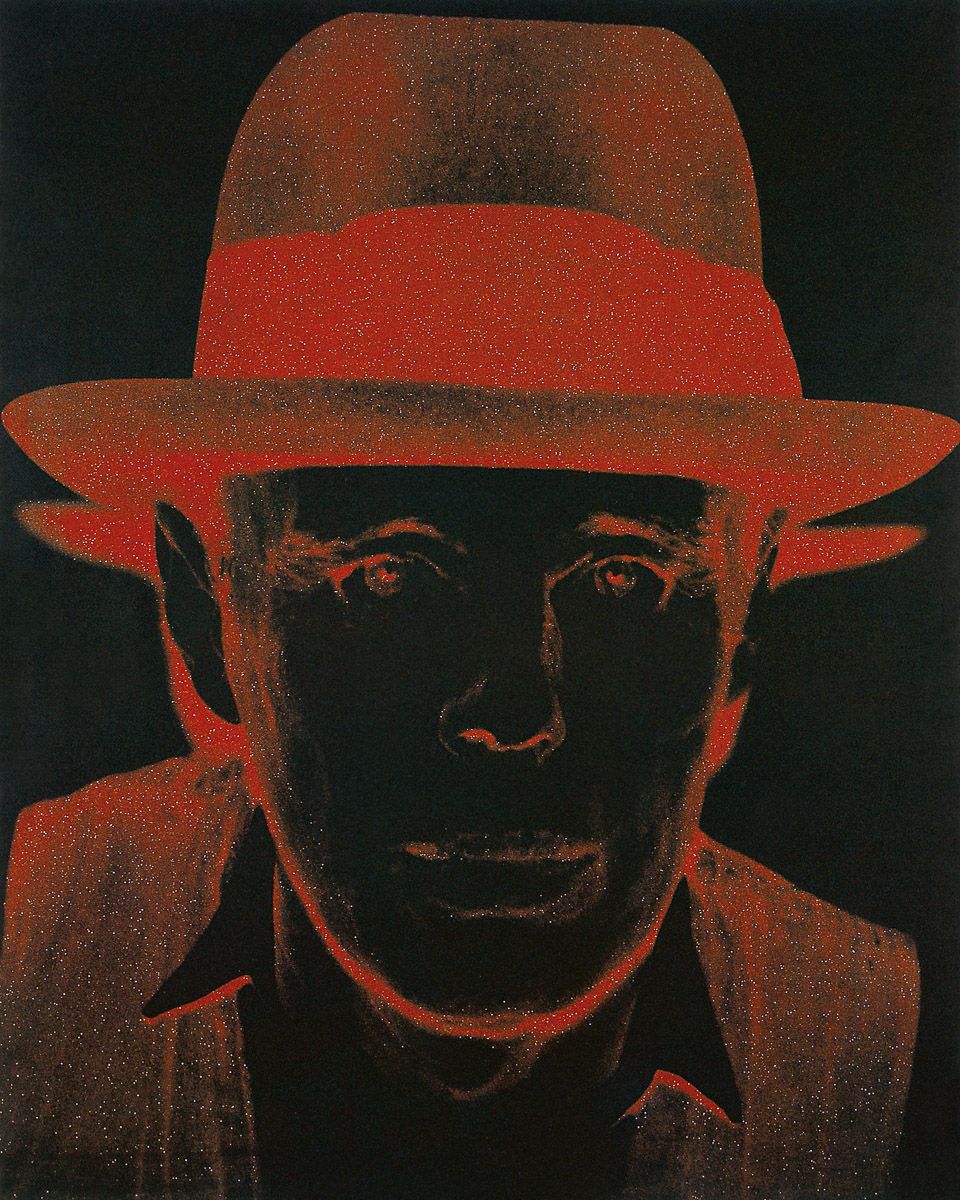

Andy Warhol, Diamond Dust Joseph Beuys, 1980. Silkscreen ink and diamond dust on synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 254 x 203.2 cm. Marx collection, Museum für Gegenwart, Berlin.

Joseph Beuys (1921-86) was perhaps the most influential of post-war German sculptors and conceptual artists. By the time of his death he was also the most highly valued artist in the world, something that certainly appealed to Warhol (who was not far behind him in the league table of top artistic earners). Beuys was one of the founders of the German Green movement, and was especially brilliant at communicating through the mass-media. He first met Warhol in New York in 1979 and the American artist was commissioned to paint his portrait the following year. Later Warhol went on to create further images of Beuys, including sets of silkscreen prints, published between 1980 and 1983. And a portrait entitled Joseph Beuys in Memoriam created after the sculptor’s death overlays a positive image of his head with camouflaged patterning. Warhol had a low opinion of Beuys’s work, but the German sculptor esteemed Warhol highly for the conceptual complexity of his art. The two exhibited their works alongside one another in Berlin in 1982 when the Marx collection – to which this portrait belongs – went on display in the National Gallery there.

This is one of Warhol’s many reversal pictures, in which he emulated the appearance of a photographic negative. The injection of glamour noted above in connection with the Skulls images was effected here not by means of an underpainting of garish colours; instead, Warhol sprinkled synthetic diamond dust over the image while the silkscreen ink was still wet, thus bonding the two together. Although the diamond dust is not easy to see in reproduction, in reality it gives off a brilliant glitter that introduces potent associations of a showbiz glitziness that is entirely and wittily appropriate to Beuys’s role as an art-world superstar.

Ed Paschke, Nervosa, 1980. Oil on canvas, 116.8 x 108 cm. Collection of Judith and Edward Neisser, Chicago.

Judging by the body-language and facial expression of the man seen here, he appears to be depressed. That feeling of despondency is certainly amplified by the generally cool colours and fairly straight lines which are evocative of the electronic patternings displayed by medical diagnostic machines.

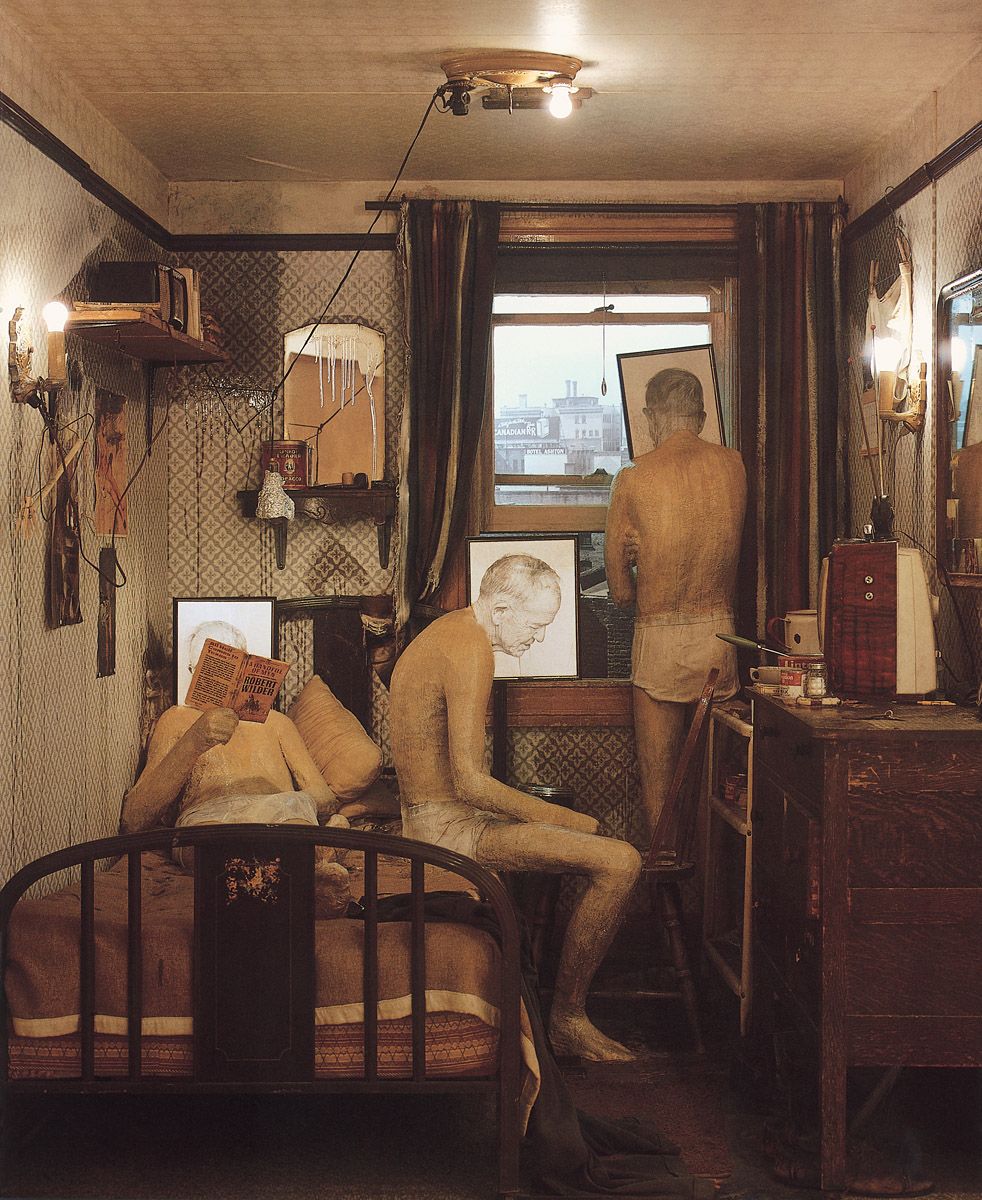

Ed Kienholz and Nancy Reddin Kienholz, Sollie 17, 1979-80. Wood, plexiglass, furniture, sink, lights, photographs, plaster casts, pots, pans, books, cans, boxes, three pairs of underwear, linoleum, leather, wool, cotton, soundtrack, glass, metal, paint, polyester resin, paper, metal coffee can, sand and cigarette butts, 304.8 x 853.4 x 426.7 cm. Private collection.

In 1965 Kienholz was walking down a second-floor corridor in the Green Hotel, Pasadena, California, when he

… passed an open door. Inside was an old man sitting on the edge of his bed playing solitaire on a wooden chair that was facing him. The room was furnished in average, seedy hotel style, and the light was slanting in through the only window in a soft and pleasant way. The thing that struck me as I walked past was the conflicting signals I read from the scene. The strongest came from the man, “What the hell are you looking in here for? This is my place and you just keep your goddamn nose out of it.” The lesser feeling was, “Oh, God, I’m so lonely, why don’t you stop and talk a little bit?”

The memory stayed with Kienholz and eventually resulted in this work, of which we are only seeing the hotel room, for the sculptor also represented the dingy hotel corridor outside. This takes the form of a wide wall pierced by two doors. A length of carpet runs along the wall, upon which are mounted fire-escape and exit-signs, plus a public telephone and a phone directory. Names, messages and numbers are scribbled all around the phone, and these have been boosted by exhibition visitors down the years. In front of the wall are a sand-filled fire bucket and a chair.

Of the two doors to the wall, one is closed and bears a toilet sign, while the other, being open, allows us to see the view reproduced here, although in reality we cannot enter the room as the aperture is sealed with a sheet of clear plexiglass. The barrier of hostility encountered by Kienholz in 1965 has now become a physical barrier instead, and it forces us to become voyeurs or people who look but do nothing.

The title of the ensemble both provides us with the name of the occupant of the room and alludes to the word ‘solitude’, which is, of course, the work’s theme. And the number in the title equally draws attention to the title of the renowned 1953 prisoner-of-war movie, Stalag 17, directed by Billy Wilder. Like a prisoner, Sollie is also caged up, although obviously not by anyone but himself.

All around Sollie are his meagre possessions. He is represented three times simultaneously, and is only ever dressed in underpants. In his first guise he lies on his bed, reading a paperback western and holding the book in one hand while he plays with his genitals with the other. His head is a framed photograph which, by its very flatness, suggests that Sollie is rather a two-dimensional personality, without the kind of inner resources that would see him though his loneliness. A framed photo of Sollie in profile also caps the man’s second appearance, sitting on the edge of his bed looking very forlorn indeed. And in his third guise we see him from the rear, his head as flat as ever and his shoulders hunched, with a hand scratching an armpit as he stares out the window. He seems the very epitome of boredom. Beyond him stretches part of the Spokane skyline as viewed from one of the decaying hotels and other condemned buildings in the old part of that city in Washington state, from which Kienholz and his wife gleaned many of the materials for this work and three related ensembles known collectively as the Spokane series. In the other sculptures Kienholz and his wife represented the check-in desk of a cheap hotel and its surrounds; a shop converted into a shrine to Jesus; and the corridor of an apartment house, none of whose six doors open but each of which gives out the sounds of everyday living when approached. In all four works Kienholz and Reddin projected the desolation that far too often stands at the heart of modern life.

Tony Cragg, Britain Seen from the North, 1981. Plastic and mixed media, 440 x 800 x 100 cm. Tate Britain, London.

Tony Cragg was born in Liverpool in 1949. After studying at Wimbledon School of Art, London, he attended the Royal College of Art, London, from where he graduated in 1977. He held his first one-man show at the Lisson Gallery, London, in 1979. He was accorded a major show at the Tate Gallery in 1989, and further exhibitions followed in Eindhoven, Washington, Madrid, Munich, Paris, and Liverpool. In 1988 he represented Britain at the Venice Biennale, and the following year he won the Turner Prize. More recently he was awarded the Shakespeare Prize. He lives in Germany.

Here Cragg portrayed himself looking across a mainland Britain lying on its side. The island is composed of fragments of the industrial detritus that constantly litters our surroundings, such as items of old clothing, discarded boots, plastic toys, bits of packaging, machine parts, and the like. The result is a highly colourful and formally varied low-relief display that memorably suggests political, industrial and social fragmentation, as well as the disorientation it produces.

Andy Warhol, Gun, 1981. Silkscreen ink, acrylic paint on canvas, 177.8 x 228.6 cm. Anthony d’Offay Gallery, London.

Given the personal suffering inflicted upon Warhol by means of a gun when he was shot in 1968, it seems natural, if somewhat masochistic, that he should have represented such objects as cultural icons, which of course they are to a great many Americans. The autobiographical significance of such images is heightened by the fact that the gun represented is a .22 snub-nosed pistol, one of which had been carried as a backup weapon in an attempt to kill the artist in 1968.

The chilling associations of the subject-matter are heightened by the fact that the portrayal of each gun is so impersonal. That neutrality accurately mirrors reality, of course, for a gun is merely a tool in the hand of the person who wields it. Once again Warhol’s visual detachment projects the utter emptiness of modern life, as represented by its artefacts.

Ralph Goings was born in Corning, California in 1928. He studied at the California College of Arts in Oakland, graduating in 1953, and at the Sacramento State College, from where he graduated in 1965. He then continued to teach painting at various institutions throughout California before retiring from teaching in 1969. He held his first solo exhibitions at the Artists Cooperative Gallery in Sacramento in 1960, and at the OK Harris Gallery in New York in 1970. Since then he has exhibited many times in New York and participated in group shows throughout America and around the world.

In the 1960s Goings worked initially in the manner of Rosenquist, and then in the style of Thiebaud. However, he moved over to photorealism by the 1970s, having found his major interests to be pick-up trucks, chain restaurants and diners. More recently he has also painted many still-lifes of the groups of objects found in diners, such as condiments, sugar bowls, metal jugs and the like.

Ralph’s Diner was located outside a small town in Pennsylvania, and it was demolished some years ago. The landscape beyond the windows was introduced from photographs taken in upstate New York. Judging by the enormous numbers of print reproductions of this canvas that are sold in shops and over the internet, it is one of the most popular photorealist pictures ever created. It is not difficult to see why, for the very subject clearly appeals to the many people for whom diners are stylish and relatively cheap places to eat. Goings certainly captures the stylishness by employing a Vermeer-like painterly technique.

The line of empty stools leads the eye towards the solitary customer, thereby inviting us to join him.

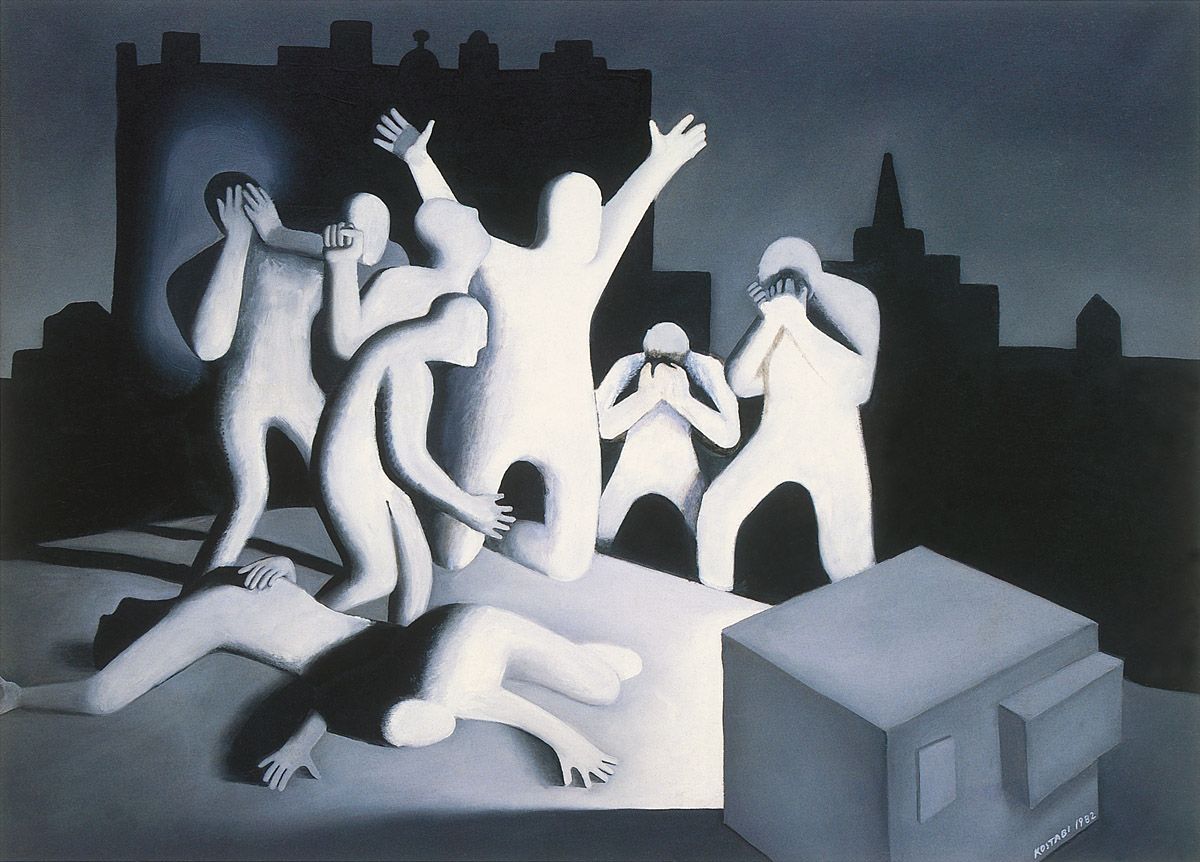

Mark Kostabi was born in Los Angeles in 1960. He studied art at California State University at Fullerton. His first solo exhibition was held at the Molly Barnes Gallery in Los Angeles in 1982, while his initial New York show was mounted at the Simone Gallery in 1983. In 1982 he opened Kostabi World, his own art-production and selling space in New York. He has exhibited globally, in 1992 holding a retrospective in Tokyo and in 1998 mounting a large retrospective in Tallinn, Estonia (from which country his parents had emigrated to the United States).

In 1975 Andy Warhol stated:

Business art is the step that comes after Art. I started as a commercial artist, and I want to finish as a business artist. After I did the thing called “art” or whatever it’s called, I went into business art. I wanted to be an Art Businessman or a Business Artist. Being good in business is the most fascinating kind of art.

In this respect Kostabi has followed directly in Warhol’s footsteps, for like most businessmen he creates virtually none of his works himself; instead, he pays teams of subordinates to think up and then create all his pictures (including the signatures affixed to the canvases). He likens himself to the chairman of some large industrial corporation, wherein he takes care of the overall strategic and marketing side of things, leaving his subordinates to produce the actual goods. Kostabi’s art-producing empire therefore parallels other commercial concerns exactly. This is not to say, however, that the results are necessarily negligible artistically, for as the present work demonstrates, Kostabi can produce some witty takes on the world. In this particular instance – which Kostabi did actually paint himself – Goya’s Shootings of 3 May, 1808 (Prado, Madrid) is updated, so that instead of seeing Spanish prisoners about to be shot by the French in the light of a large lantern resting on the ground, that box has become a television set holding its anonymous viewers in thrall.

Sir Peter Blake, The Meeting or Have a Nice Day Mr Hockney, 1981-83. Oil on canvas, 97.8 x 123.8 cm. Tate, London.

In this update of the French painter Gustave Courbet’s 1854 group portrait The Meeting or Bonjour, Monsieur Courbet (Musée Fabre, Montpellier), art renews itself amid the hedonistic backdrop of southern California. Courbet’s famous canvas shows him being welcomed by his patron Alfred Bruyas to the provincial French town in which the picture was painted and now hangs. Here Peter Blake welcomes his friend David Hockney to Venice Beach, California. This is a witty reversal of the truth, for Blake was always the visitor to the United States while Hockney resided in California. To the left the British abstractive painter Howard Hodgkin stands in for Bruyas’s manservant Calas who also appears in the Courbet oil.

Hockney holds a giant paintbrush. In addition to substituting for the painting gear carried by Courbet, this could have stemmed from reality, for an American company, Think Big, used to produce such artefacts in its range of huge ornamental products. Blake appropriated the crouching blonde and other figures from roller-skating magazine illustrations, while the setting derived from photos he had taken in Venice Beach in 1980.

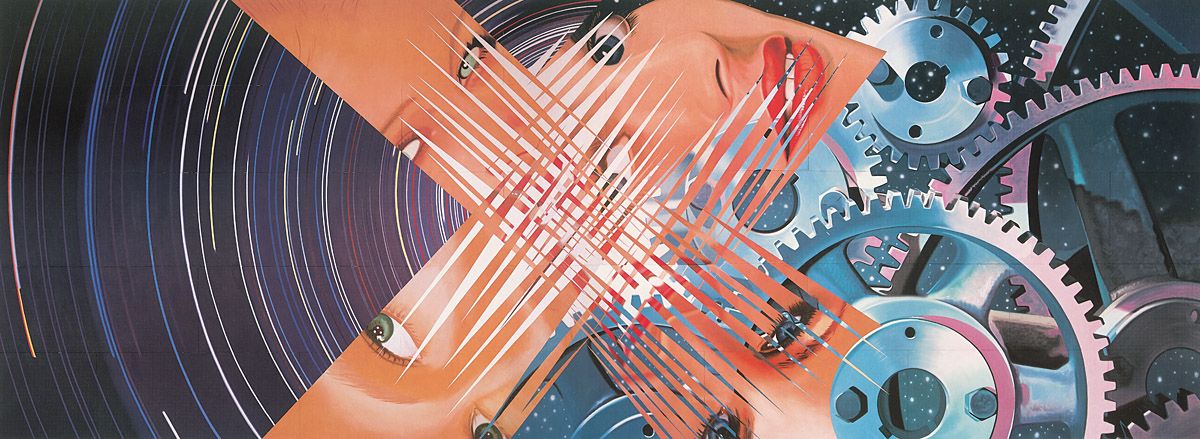

James Rosenquist, 4 New Clear Women, 1983. Oil on canvas, 518.2 x 1402.1 cm. Collection of the artist. Art © 2006 James Rosenquist/ Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Giant cogwheels turn on the right, as slivers of the faces of four somewhat artificially glamorous women interpenetrate at the centre, and the tracks of stars as recorded by time-lapse photography curve around on the left. By their contrast, the large numbers of circles to right and left heighten the pictorial impact of the X-shape at the centre.

In overall terms the image clearly constitutes a metaphor for the way in which many women have often been reduced to socially fragmented beings by the mechanistic pressures of modern life. Given such a message, the punning title of the work seems both accurate and ironic.

Allan McCollum, Plaster Surrogates, 1982-84, Enamel on cast Hydrostone, various sizes. Private collection.

Allan McCollum was born in Los Angeles in 1944. His first solo exhibition took place at the Jack Glenn Gallery in Corona del Mar, California, in 1971 and subsequently he has held many shows across the United States, Europe and the Far East. He has also worked on several public projects in the USA, France, Sweden and Mexico. Between 1988 and 1998 retrospectives of his work were mounted in Frankfurt, Eindhoven, Valencia, Malmo, London, Hanover and Lille.

The multitudinousness of things, and endless diversity within that repetitiousness, has proven central to McCollum; as he recently stated, he has “spent over 30 years exploring how objects achieve public and personal meaning in a world constituted in mass-production.” To that end he first made his reputation with a group of extremely varied Surrogate Paintings he created after 1978, and subsequently he has maintained it with the Plaster Surrogates which are large numbers of monochromatic variants of those coloured, painted objects. Given that human beings are constant variants of two basic models, the overall repetitiousness and internal variation of McCollum’s art parallels our reality exactly.

McCollum has spoken of the Surrogate Paintings in terms that are equally applicable to the Plaster Surrogates that derived from them:

The motivation behind making the Surrogate Paintings was to represent something, to represent the way a painting ‘sits’ in a system of objects. If you look at installation shots, or pictures taken of art galleries – that was the picture I had in mind. I was trying to reproduce that picture of an art gallery in three dimensions, a tableau. So with the Surrogate Paintings the goal was to make them function as props so that the gallery itself would become like a picture of a gallery by re-creating a gallery as a stage-set. To me, this was a clear representation of the way paintings looked in the world, irrespective of whether there’s a ‘representation’ within the painting or not.

In the Plaster Surrogates, therefore, as in their Surrogate Paintings forbears, we are necessarily looking at a distanced comment upon the multitudinousness of objects that collectively constitute the ‘art world’. In an age in which – as Joseph Beuys once commented – ‘everyone is an artist’ and the planet is increasingly flooded with framed pictures, McCollum’s statements about vast ensembles of such artefacts seem very apt.

Keith Haring, St Sebastian, signed, titled and dated ‘August 21 1984’ on the overlap, 1984. Acrylic on muslin, 152.4 x 152.5 cm. Courtesy Tony Shafrazi Gallery, New York.

Keith Haring was born in Kutztown, Pennsylvania in 1958. Between 1976 and 1978 he studied art in Pittsburgh and then moved to New York where he attended the School of Visual Arts. He exhibited extensively in New York before mounting his first solo show at Club 57 in New York in 1981. His first gallery display followed in 1982. In 1983 he exhibited in New York, London and Tokyo, while during the next year he created murals in Australia, Brazil and the USA. In 1985 he began painting on canvas, as well as took up sculpture and stage design. Later he opened a store selling Keith Haring products, created further murals, exhibited widely in America and Europe, and worked extensively on behalf of children’s charities. He died of AIDS in 1990.

The principal feature of Haring’s work is a linearity we usually associate with cartoons. He had always felt an affinity with cartooning, although he regarded the activity as somewhat inartistic until he saw works by Dubuffet, Alechinsky, Christo, Warhol and anonymous graffiti artists in New York. In 1981 Haring created his first chalk drawings on sheets of black paper pasted over expired advertisements in New York subway stations. He did so as an expression of his belief that art should be made freely for the people. In the process he also discovered the curious respect people pay to art, for although chalk is easily effaced, generally his works were respected. (Sadly this was not the case with his subway drawings of the mid-1980s, for by then their economic value was so great they were usually stolen shortly after having been made; as a result, Haring gave up creating them.)

By the 1980s the instant communicability of Haring’s images had made him a huge hit with the public, if not necessarily with art critics. We can easily see why the public liked his work in this particularly witty example of his output at its best. St Sebastian is thought to have been a secret Christian in 3rd-century Rome, where he was a member of the Imperial Guard. When the Emperor Diocletian found out, he ordered Sebastian to die by being tied to a tree and pierced with arrows; although the future saint survived the ordeal, he was later cudgelled to death. Because of the secrecy of the saint’s religion, the fact that his body was repeatedly pierced, and the way he was often painted as a beautiful young man, he has become the unofficial patron saint of gays, of whom Haring was one.

Here Haring’s saint looks decidedly Picassoesque and ‘unbeautiful’. In a curiously prescient pointer to 9/11, his sides are pierced by airplanes, rather than arrows. The erection is, of course, a reference to the homosexual associations of the saint.

Sandy Skoglund, Germs are Everywhere, 1984. Live model, furniture, chewing gum, Cibachrome photograph, 76.2 x 101.6 cm. Private collection.

Sandy Skoglund was born in Quincy, Massachusetts, in 1946. She studied art at Smith College, Northampton, Massachusetts between 1964 and 1968, during which time she spent her junior year at the Sorbonne and at the École du Louvre in Paris. She then attended graduate school at the University of Iowa, from where she graduated in 1972. That same year she moved to New York where she worked through the rest of the decade as a conceptual artist. By the end of that period her work had come into more concrete focus, and she caused quite a stir with her installations/photographs Radioactive Cats and The Revenge of the Goldfish at the Whitney Biennial in 1981. Since then she has created installations around the world. In 1997 a retrospective of her work toured various leading museums throughout the United States.

Skoglund makes installations using people and objects, which she then photographs. Occasionally she markets the installations, while the photographs are sold widely, both as limited edition Cibachrome prints – one of which is reproduced here – and as books, posters and postcards. This strategy permits her to reach a very wide audience.

Many of Skoglund’s works can border on the surreal, as with Revenge of the Goldfish, which shows a girl asleep, a boy sitting on the edge of her bed, and an entirely blue room filled with large, richly-coloured goldfish. But surrealism does not seem so intrusive in the present work, with its suburban housewife, her hair in curlers, resting with a beverage in her hand and presumably looking with satisfaction upon the living-room she has just cleaned. However, as the title tells us and the blobs on the walls demonstrate, germs are everywhere….

This is possibly the first sculpture ever made using chewing gum as one of its materials.

Ed Paschke, Electalady, 1984. Oil on canvas, 188 x 233.7 cm. Collection of James and Maureen Dorment, Rumson, New Jersey.

Colouristic breakdown as seen here is surely familiar in the age of advanced photography, electronics and the mass-media. The horizontal lines suggest the patternings of medical diagnostic machines, the dark, glowing greens of the flesh might well evoke X-ray photographs, and the blank orange-yellows of the eyes take us into strange psychological territory indeed. The garish red of the lips links subtly to the heightened banality of the portraits of Marilyn Monroe by Andy Warhol, the artist that Paschke considered to be the most significant creative figure in America.

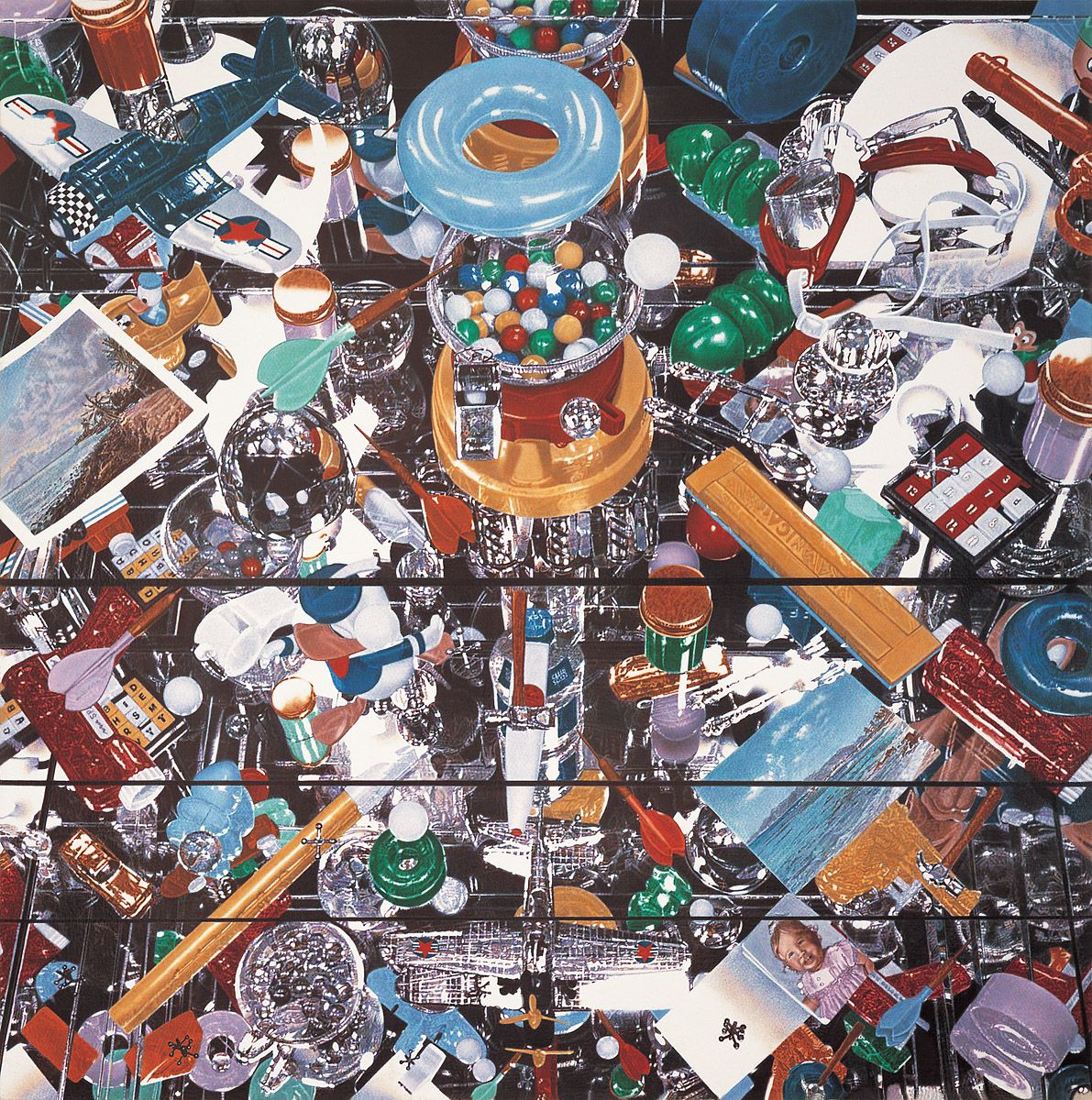

Tim Head, State of the Art, 1984. Cibachrome photograph, 18.9 x 274 cm. Arts Council collection, The South Bank Centre, London.

Tim Head was born in London in 1946. Between 1965 and 1969 he studied at the University of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, where one of his teachers was Richard Hamilton. In 1968 he worked in New York as a studio assistant to Claes Oldenburg. The following year he attended an advanced course run by the sculptor Barry Flanagan at St Martin’s School of Art, London. He first exhibited in London in 1970. Since then he has shown extensively throughout Britain and continental Europe, as well as in New York. In 1987 Head was awarded the first prize at the John Moores exhibition of contemporary art in Liverpool. A retrospective of his work was held at the Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, in 1992.

This was the first of Head’s large Cibachrome photographs of artificial cityscapes fashioned from manufactured objects. After carefully assembling a vast array of consumer products, including sex toys and games with militaristic and fascist themes, Head had this picture taken by the photographer Richard Davies. In 1989 the artist described the work as:

A city skyline

A synthetic landscape with consumer products

An accumulation of technological fallout

A gloss of seductive surfaces

A conglomerate of objects that are merely signs

A cemetery of images

A techno-military-erotic-leisure complex…

Picture of a disposable present

A still-life

It is easy to apprehend the ‘city skyline’, with its huge phallic objects standing for skyscrapers. Naturally, the title of the work refers to cutting-edge technology and although many of the artefacts are now obsolete, the work still typifies the altars that we all constantly fashion from the objects of mass-consumption.

Don Eddy, C/VII/A, 1984. Acrylic on canvas, 190.5 x 152.4 cm. Courtesy of the Nancy Hoffmann Gallery, New York.

Don Eddy was born in Long Beach, California in 1944. Between 1967 and 1970 he studied at the University of Hawaii in Honolulu, and at the University of California in Santa Barbara. He held his first solo exhibition at the Ewing Krainin Gallery in Honolulu in 1968, and his first New York show at French and Co. in 1971. Subsequently he has exhibited all over the USA, as well as in Europe and Japan.

Of late, Eddy has created pictures from photographs of landscapes and shop windows, but for the canvas reproduced here, as for much of his work made during the 1980s, he carefully arranged collections of kitsch and other objects upon reflective shelves in his studio. He then photographed the displays many times in both colour and monochrome, using varying depths-of-field for the images. A slide taken from each print made for a given work was then projected onto a canvas, over which the tonal values were initially established before the final painting was undertaken. Eddy is a master of the airbrush, a tool he learned to use when working in his father’s car customising workshop as a young man. Everything in his paintings is made using this device, which produces seamless transitions from one colour to another.

Eddy’s crowded, richly-coloured, brilliantly-lit and sharply highlighted still-lifes act as vivid reminders of the glut of artefacts now filling the world. Again, photorealism serves to explore the nature of perception, while equally commenting upon the values of consumerism and mass-culture.

Arman, Office Fetish, 1984. Group of telephones, 135 x 76 x 76 cm. The Detroit Institute of Art, Michigan.

By 1984 the mobile revolution was not even in its infancy and so it would be wrong to suggest that Arman was being prescient here. But the telephone as an integral part of commercial life had been around for a long time, so the title of this accumulation was certainly apt, especially as many office workers did fetishise their phones by the 1980s and, indeed, increasingly do so now.

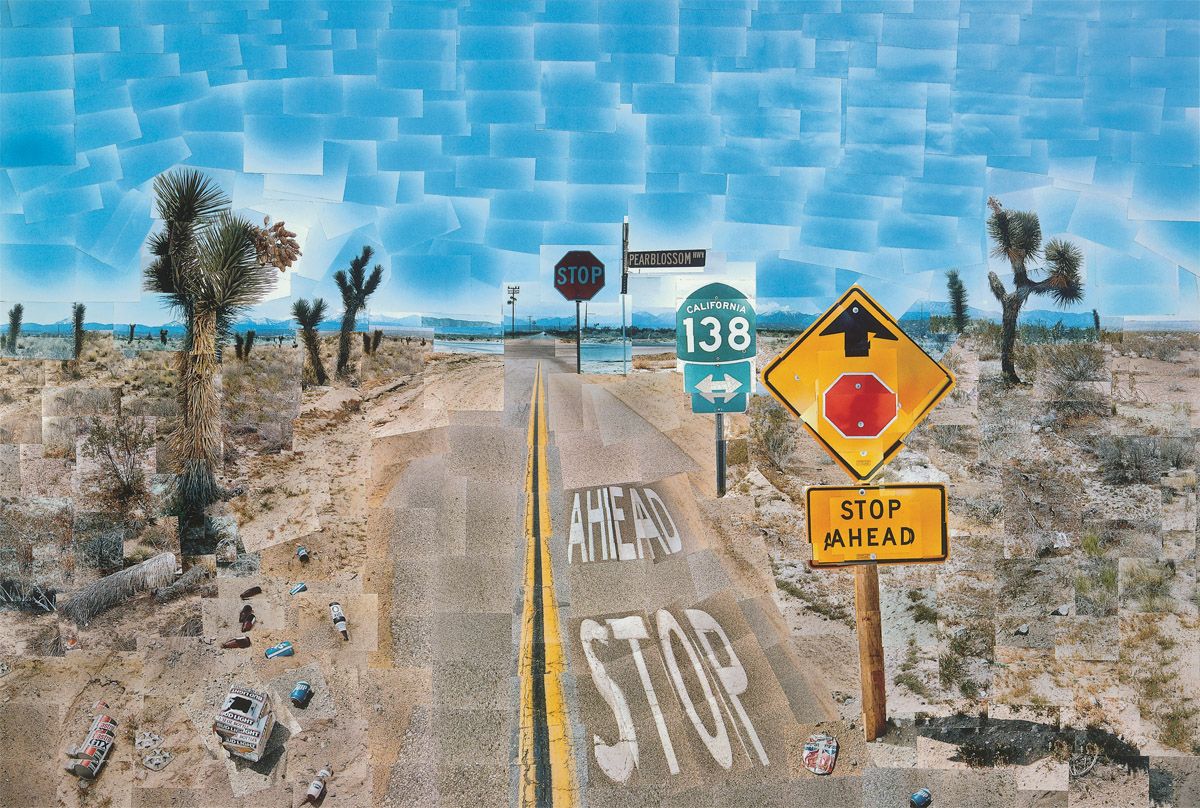

David Hockney, Pearlblossom Hwy., 11-18 April 1986, no. 2, 1986. Photographic collage, 198 x 282 cm. Collection of the artist.

Although by 1982 Hockney had long used photography to provide information for his paintings, early in that year he began making large photocollages out of sizable numbers of Polaroid instant-development photographs. He did so in order to investigate new ways of exploring pictorial space and the psychology of perception. Over the following four-and-a-half years he created more than 370 such composite images, not only employing Polaroid photography but also 110 and 35mm photography as well. The present work was his final photocollage and it is made up of over 600 separate Polaroid prints. For parts of the picture, such as the road signs, the artist took his camera up a ladder in order to avoid distorting the internal perspectives.

The final composite not only forces us to look at each part of the image with new eyes; it also projects the bleakness of a landscape bestrewn with all the familiar debris of an uncaring consumer society. Naturally, the abundant signs and injunctions make the landscape even uglier, and given that they clutter a fairly empty place, the picture sardonically comments upon unnecessary human intrusion within the natural world.

Andy Warhol, Camouflage Self-Portrait, 1986. Silkscreen ink on synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 208.3 x 208.3 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The camouflage patternings seen here were derived from some standard United States military camouflage that Warhol had purchased in an army surplus store in 1986. Initially he used the camouflage to create a group of abstract paintings, but eventually he put it to much more fruitful use in representational images, as here.

After 1963 Warhol became a master at masking his real self from public gaze. To art critics, art historians and media questioners he usually went out of his way to appear naive, mentally slow, emotionally detached and even robotic. Yet this was a complete act, for in private Warhol was very worldly, mentally quick, frequently emotional, always manipulative (which is a true measure of his worldliness, for manipulativeness necessitates an understanding of human character) and anything but robotic. And intellectually he was highly sophisticated, as his works make abundantly clear. The late series of camouflaged self-portraits therefore project the real Andy Warhol in a very direct fashion indeed, for camouflage is a means of masking true appearances.

Naturally, the camouflage in these late self-portraits forces the images to the interface with abstraction, a frontier the painter had explored very often in previous works. The spikiness of the hair contrasts strongly with the swirling, curvilinear shapes of the camouflage, and together they imbue the image with a startling visual impact.

Haim Steinbach, Pink accent2, 1987. Two ‘schizoid’ rubber masks, two chrome trash receptacles, four ‘Alessi’ tea kettles on chrome, aluminium and wood shelf, 139.7 x 279.4 x 58.4 cm. Milwaukee Art Museum, Wisconsin.

Haim Steinbach was born in Rehovot, Israel, in 1944. His family moved to the USA soon afterwards, and he took out US citizenship in 1962. Between 1962 and 1968 he studied at the Pratt Institute, Brooklyn, part of which involved a year at the Université d’Aix, Marseilles. Between 1971 and 1973 he completed his studies at Yale University. His first exhibition was held at the Sonnabend Gallery, New York in 1990, since when he has shown all over the world.

Steinbach has specialised in arranging common consumer artefacts on shelves of his own devising that visually relate in form, size and colour to the objects they support. Of course, by taking his articles from the real world, Steinbach follows in Duchamp’s footsteps, although unlike the creator of the first ‘ready-mades’, he does not challenge the nature of art. Instead, he divorces everyday objects from their normal contexts and, by means of repetition, unusual juxtapositions of disparate objects, and the creation of visual consonances and dissonances, he forces us to a new awareness of the visual values of articles we normally take for granted. He can also occasionally introduce wit to the proceedings, as here.

Because the trashbins are so streamlined, brilliantly reflective and hard, and the kettles so bright, curvilinear and rigid, they contrast greatly with the soft, pliable forms of the masks. Moreover, the impersonality of the metal objects heightens the subjective quality of the masks equally by contrast, making those faces look very manic indeed.

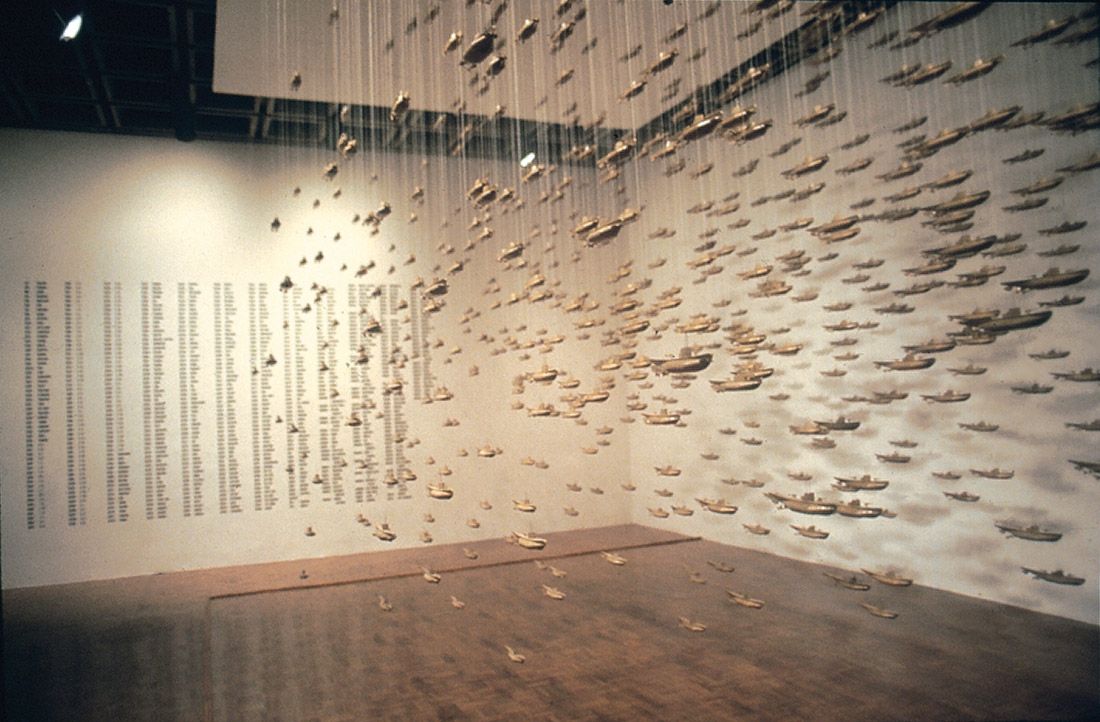

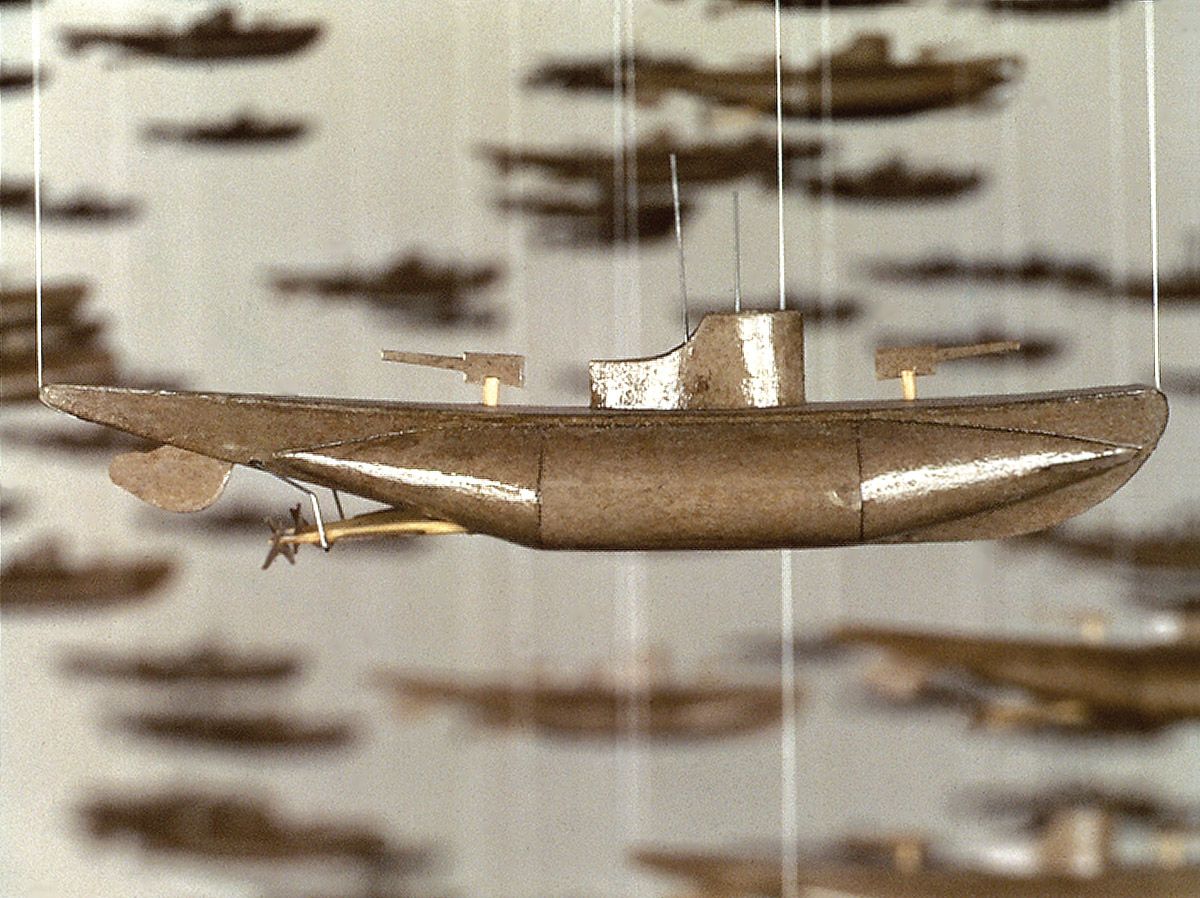

Chris Burden, All the Submarines of the United States of America, 1987. 625 cardboard, wood and wire model submarines, 7.6 x 20.3 x 4.4 cm each; overall 96 x 240 x 144 cm. Dallas Museum of Art, Texas.

Chris Burden was born in Boston, Massachusetts in 1946. He studied art at Pomona College, Claremont, California, from where he graduated in 1969, and architecture, physics and art at the University of California at Irvine, from where he graduated in 1971. He first exhibited in Los Angeles and Cincinnati in 1974, and in New York in 1977. Subsequently he has made site-specific works internationally, and exhibited all over the world.

For Burden, art can and should mean almost anything. Among his many ways of expressing himself since 1971 he has spent five days crouched inside a tiny locker; he has had himself shot; he has risked electrocution by thrusting electric cables into his chest; he has had nails driven through the palms of his hands as he lay face-up on the back of a car; he has set fire to himself; he has created a mechanism by which visitors to an art gallery gradually push a wall of that building down simply by entering a space; he has created a million-dollar assembly of 100 one-kilo gold bricks surrounded by matchstick men; he has created an alternative Vietnam War memorial to the one in Washington DC, in the form of twelve huge copper panels engraved with the names of the three million Vietnamese killed during the Vietnam War; and he has promoted touring displays of videos showing disasters in California because, as he says, “Nothing makes people feel better than seeing disaster fall upon a rich and excessive society in a distant place.”

The present, breathtaking installation was first exhibited at the Whitney Biennial in New York in 1987. It records all 625 submarines that had constituted the underwater fleet of the United States Navy between the inception of that branch of the service in 1897 and 1987; the names of each of the vessels are listed on a wall of the gallery. The small cardboard models are not differentiated in shape, and thus do not reflect the technological evolution of the submarine over those ninety years. The models hang by wires of varying lengths from the ceiling, and because of their overall density they look like a shoal of tiny fish.

This is one of those many sculptures of the second half of the twentieth century where the component objects do not matter – it is their aggregation that is all-important. The ensemble vividly projects the sheer vastness of the modern military machine, with all its ramifications of political determination, massive finance and industrial might.

Chris Burden, All the Submarines of the United States of America, detail, 1987. 625 cardboard, wood and wire model submarines, 7.6 x 20.3 x 4.4 cm each; overall 96 x 240 x 144 overall. Dallas Museum of Art, Texas.

Rose Finn-Kelcey, Bureau de Change, 1987-2003. 12,400 coins, false wooden floor, security guard, video surveillance camera and colour television monitor, viewing platform and spotlights. Weltkunst collection of British Art, on long-term loan to the Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin.

Rose Finn-Kelcey was born in Northampton, England, in 1945. She studied at Ravensbourne College of Art, Surrey, and Chelsea School of Art, London. Her first solo exhibition was held at the Chisenhale Gallery in London in 1992. She has shown and created work in Mexico and South Korea, as well as across Britain.

The output of Finn-Kelcey has ranged from performance activities, to flags, to the creation of atmospheric environments. However, this is arguably her most imaginative, substantial and impressive work to date. It has been installed seven times: in 1987 in Newcastle, Bradford and Manchester; in 1988 in London; in 1990 in New York and Oxford; and in 2003 in Dublin. Its centrepiece is a re-creation of one of Vincent van Gogh’s Sunflower paintings. This is made not in paint but in coins, which in Dublin comprised 12,400 Euros and defunct Irish Punts. The medium of money is most apt of course, for poor van Gogh only ever sold a single painting during his lifetime, whereas the version of Sunflowers reproduced by Finn-Kelcey is the one sold to a Japanese insurance-company executive in 1987 for the then-world record sum of 24.5 million pounds sterling. The translation of art into money is therefore totally congruent, and it makes a powerful point about the extraordinary commodification of art in our time. Moreover, as Finn-Kelcey’s title makes clear, art is now a form of exchangeable currency, as mafiosi and drugs gangsters know only too well, for they often steal valuable works of art for use as collateral in their nefarious deals.

A suitable visual perspective upon the van Gogh-as-money is afforded by the viewing platform. The security guard, video surveillance camera, television monitor and fake wooden floor all induce associations of the highly artificial but rigorously controlled conditions that often pertain when immensely valuable works of art are lent or sent out by their owners, as happened in 1963 with the loan of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa by the Louvre, Paris, to the Metropolitan Museum, New York, and in 1964 with the Vatican’s display of Michelangelo’s Pietá at the New York World’s Fair (where it could only be witnessed by people standing on a slowly moving walkway). Naturally the security guard and video apparatus are necessary anyway, for if they were not present who knows what might happen to the cash?

Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen, Spoonbridge and Cherry, 1987-88. Stainless steel and aluminium painted with polyurethane enamel, 9 x 15.7 x 4.1 metres. Minneapolis Sculpture Garden, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis.

Spoonbridge and Cherry forms part of a succession of huge objects created by these two artists after they first collaborated on a representation of a garden trowel in 1976. Among their jointly-made sculptures are elegant and witty treatments of a baseball bat, pool balls, Robinson Crusoe’s famous umbrella, a hat in three stages of coming down to earth, a pickaxe, a garden hose, a small version of a proposed bridge in the form of bent screws, a stake-hitch type of rope knot, some building tools in a seemingly precarious balancing act, a knife slicing through a wall, a dropped bowl with scattered slices and pieces of fruit, an erect pair of binoculars, a rubber stamp, a handsaw in the process of sawing, an up-ended ice cream cone, and a representation of Cupid’s bow and arrow. All of these and many more pieces adorn public spaces, museums, offices and factory buildings, and undoubtedly they always intervene between the viewer and normality, hopefully to stimulating effect.

Here Oldenburg and van Bruggen took an enormously mundane mass-produced object and, by enlarging it, subtly transformed our perceptions of reality. Oldenburg has stated that he often receives his best inspirations when seated at the dinner table and he had long contemplated creating a sculpture of a spoon, for in 1962 he had acquired a kitsch novelty item in the form of a spoon resting on a blob of fake chocolate. The cherry was van Bruggen’s idea, being inspired both by the formal geometry of the proposed sculpture-garden setting in Minneapolis, and by the associations of Versailles induced by that formality, as well as by the rigid dining etiquette imposed at the French court by King Louis XIV.

The work stands in the eleven-acre sculpture garden, amid a pond shaped to look appropriately like a linden seed, for linden trees line the walkways that crisscross the garden. A fine trickle of water spreads continuously across the cherry from the base of its stem, in order to make it gleam constantly, while another spray of water simultaneously trickles from the top of the stem down over the cherry, on to the spoon and into the pond below. Naturally, in winter this water freezes, changing the beauty of the piece entirely.

The spoon weighs 2630 kg, the cherry 544 kg; both were created at two New England shipbuilding yards. In order to avoid staining the bowl of the spoon, purified city water had to replace well water as the source of the liquid. The work was entirely repainted in 1995, a fate that befalls most outdoor coloured sculptures.

Photographs of the piece are the most requested images of the Walker Art Center, which is surely a measure of how the transformational power of art remains vital in a mass-culture that often provides plenty of glitz and glamour but almost always lacks magic, or at least the kind of magic provided by Oldenburg and van Bruggen.

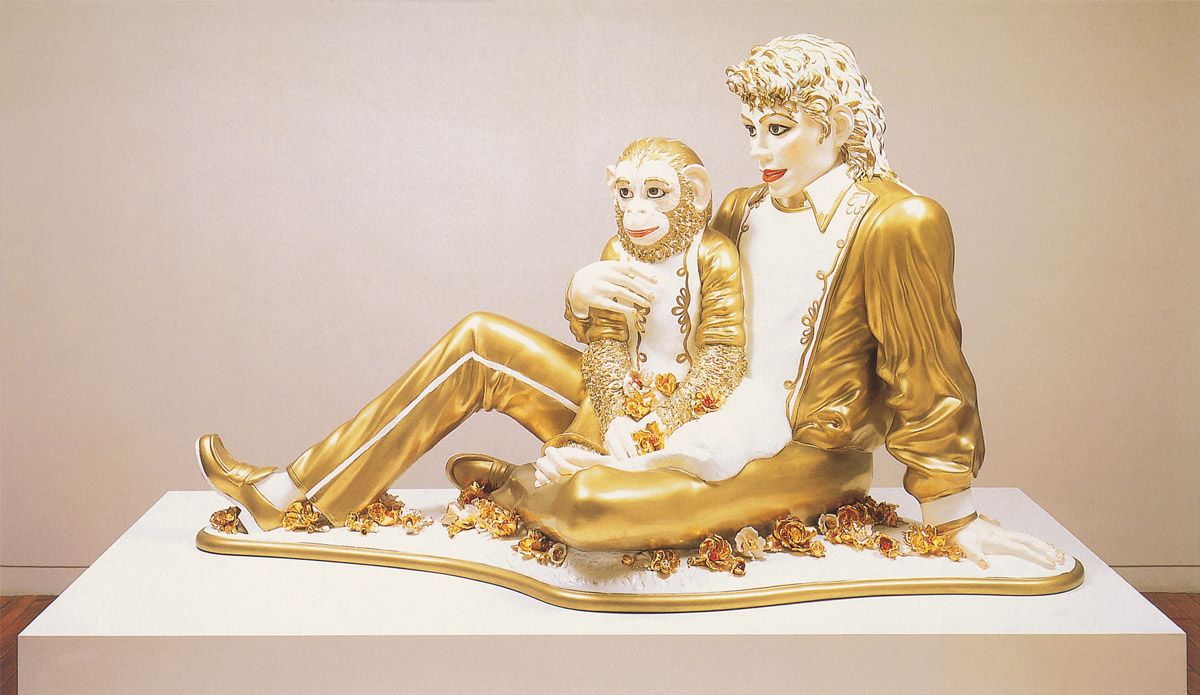

Jeff Koons, Michael Jackson and Bubbles, 1988. Porcelain, edition of 3, 106.7 x 179 x 81.3 cm. Sonnabend Gallery, New York.

Jeff Koons was born in York, Pennsylvania in 1955. Between 1972 and 1975 he studied at the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore, and between 1975-6 at the Art Institute of Chicago, where he was taught by Ed Paschke. In 1976 he returned to the school in Baltimore for a further year. He then worked as a Wall Street commodities broker, as well as at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. His first exhibited work was a window installation at the Monument Gallery, New York, in 1980, and in 1985 his first solo show was mounted at the same gallery, as well as in the Feature Gallery, Chicago. He has since exhibited all over the world. A large retrospective toured Minneapolis, Aarhus and Stuttgart in 1993.

In his first mature works Koons dealt with commonplace consumer artefacts such as vacuum cleaners. He also made a fairly remarkable piece of sculpture by bringing two basketballs into gravitational equilibrium. But subsequently, like Warhol and others, he specialised in attacking the banality within modern culture by magnifying it to the point of absurdity. Such is the case here. As if the bogus prettiness, sentimentality and artificiality of Michael Jackson were not enough to stomach in reality, Koons has given us the singer as a golden-white boy, along with his pet. By association, the gold reminds us of the huge wealth Jackson has engendered, while the whiteness underlines the musician’s largely unsuccessful attempts to deny his true colour.

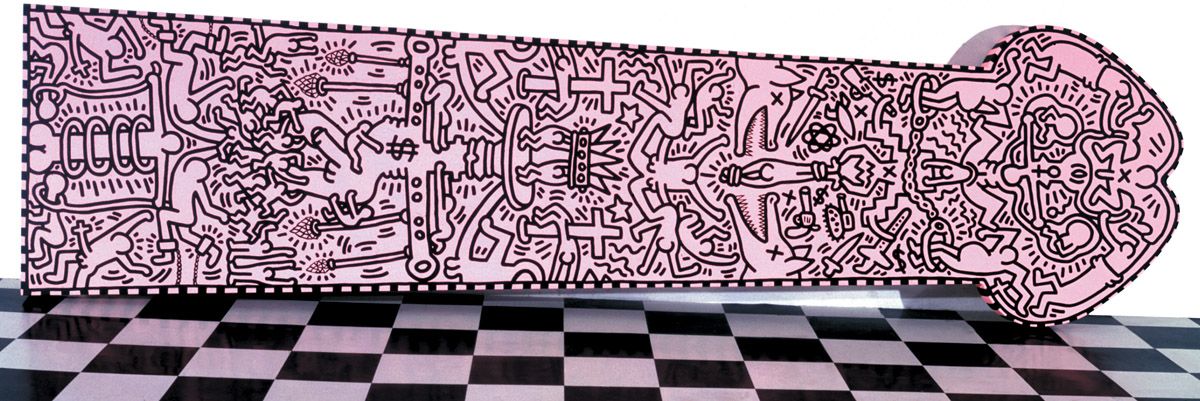

Keith Haring, The Great White Way, 1988. Acrylic on canvas, 426.7 x 114.3 cm. Estate of Keith Haring.

This large phallus-shaped canvas is composed of subsidiary images, rather like some gigantic, horizontal and flat totem pole. Many of the images pertain to the processes, conditions and artefacts of modern life, including industrial activity, weaponry, money-making and AIDS. The latter link is especially enforced by the picture’s underlying pink colour, with its gay associations.

At the base of the huge penis a man/phallus struggles to free himself from a snake or spring coiled round him. His hands hold penises that curl themselves around the heads of others. On either side men sport crucifix-shaped penises, while above the man a gaggle of people are engaged in a fight. Further up a male metamorphoses into a machine, with a dollar sign on his/its chest. Small figures cling to him/it while others struggle to turn the large handles and cogs that stand where his/its head should be. At the top of this machine a platform supports two figures bearing a crown; on either side men are pierced by large crosses. Yet further up still a man brings forth other men, while on the next level two pigs leer at a bound, dangling man whose feet are held by a vaguely human figure who forms one of two links in a chain; a metallic chain also binds two pregnant women on either side of this first fetter. All around are guns, a tank, a nucleus, knives, scissors, an airplane, a bomb and yet another dollar sign. The top human link in the chain emanates from the womb of a woman whose head doubles as the head of yet another woman, from whose outstretched hands emanate two more wombs, each containing babies; the female ideogram appears on her midriff. Finally, at the apex of all this activity a winged male with an erection is cojoined on either side by men emerging from other men whose bodies are shaped like condoms.

For a New Yorker, which Haring became by adoption, the ‘Great White Way’ is Broadway, with its teeming nightlife and, in its theatrical district at least, its gay cruising, as the artist was well aware. Of course in the context of a phallus the title also clearly refers to the duct through which semen is passed, although it is difficult to imagine how the fluid could easily do so here, given that the organ is so blocked with people and things.

Ashley Bickerton, Tormented Self -Portrait (Susie at Arles), 1988. Mixed media construction with black padded leather, 228.6 x 175.2 x 45.7 cm. The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Ashley Bickerton was born in Barbados in 1959. He studied at the California Institute of the Arts, from where he graduated in 1982, and on the Whitney Museum Independent Studies Program, from which he graduated in 1985. By that time he had already held his first solo exhibition, in the Artists’ Space, New York, in 1984. Since then he has shown in New York, Chicago, Paris, La Jolla, San Diego, Philadelphia, Houston and Lausanne.

Bickerton first rose to prominence with industrial-looking objects in the present vein. The ‘Susie’ of the title is a reference to himself in his alternative sexual persona, while the mention of Arles suggests a link between his dual sexual self and the torments of Vincent van Gogh in that Provençal town. Yet the ‘torment’ of the self-portrait’s title is clearly ironic, for the object looks utterly mechanistic, with the many corporate logos embellishing it representing the artist’s consumerist interests. Bickerton’s signature, which twice appears vertically near the bottom, takes its natural place alongside all these tokens of commercial identity.

David Mach, One Hundred and One Dalmatians, temporary site-specific installation at the Tate Gallery, London, 28 March-26 June 1988. Painted plaster dogs, electronic and electrical goods, beds, chairs and other items of furniture, carpet, approximately 16 x 16 x 4 metres.

David Mach was born in Methil, Fife, Scotland, in 1956. He studied at Duncan Jordanstone College of Art, Dundee, between 1974 and 1979, and at the Royal College of Art, London, between 1979 and 1982. At both institutions he won numerous prizes, both for sculpture and for drawing. He held his first London exhibition at the Lisson Gallery in 1982. Since then he has exhibited all over the world, often creating site-specific installations on a massive scale.

This was one of Mach’s smaller ensembles. Representations of around fifty animals in four different poses were first cast in white plaster in a workshop and then transported to the Tate where they were painted with black spots. Some of the dogs had their jaws cut open – so that they would subsequently appear to be biting the furniture – and all the cracks in the plaster were then filled. The dogs that would be weight-bearing were cut open for internal strengthening by the insertion of metal armatures. All this work took place on site, watched by the public.

One Hundred and One Dalmatians did not illustrate the Walt Disney film but posited another such cinematic congregation of dogs taking over a house and forming its own arrangement of things – in other words, nature striking back at the modern world, as represented by its consumer goods.

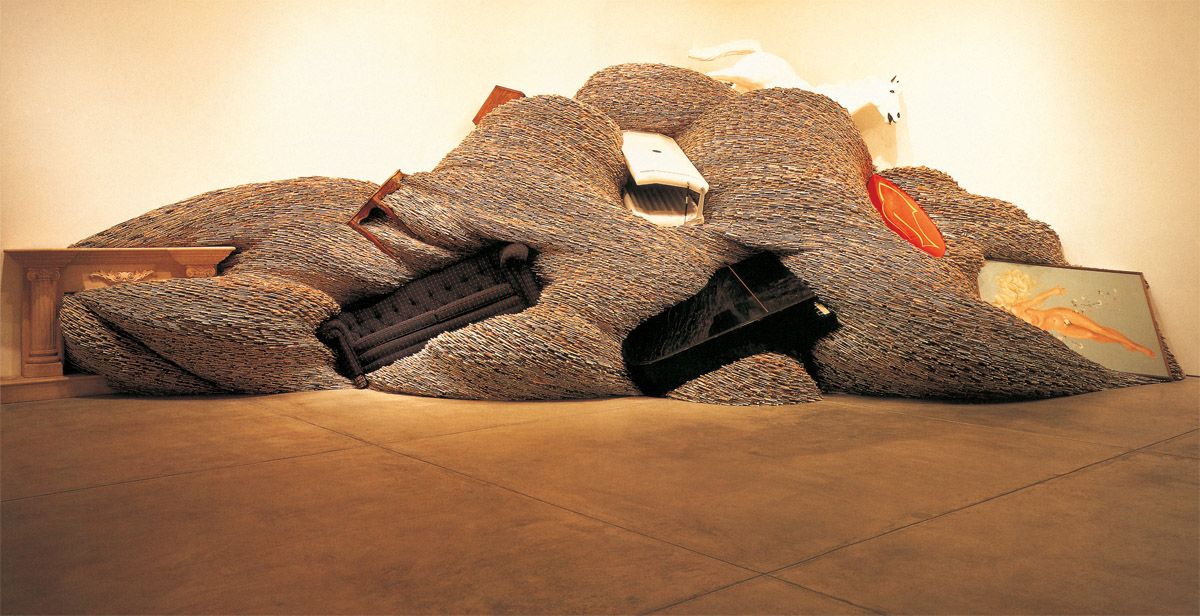

Chris Burden, Medusa’s Head, 1990. Rocks, concrete, steel, plywood, miniature railway tracks and vehicles, paint, 4.2 metres in width, 4.9 metres in height. Collection of the artist.

In ancient mythology Medusa was one of three sisters, the Gorgons, whose staring eyes, fangs, dangling tongues and snakes for hair made them so repulsive they turned everyone who gazed upon them into stone. Here Burden drew upon such a creature to create a stunning metaphor for the way our species is currently transforming our planet into something just as ugly. Miniature railway lines, complete with small locomotives and freight cars, snake their way across the shattered rocks, gorges and crevices of the orb to represent Medusa’s hair, although because of the laws of gravity the trains are stuck down and can only move in our minds.

The sculpture hangs from the ceiling and weighs 5080.3 kg, a factor that has forced at least one gallery to have its supporting beams strengthened.

Tony Cragg, Zooid, 1991. Steel bins, two sand-blasted porcelain statues, 93 x 37 x 30 cm each. Courtesy Lisson Gallery, London.

Cragg possesses a strong sense of metaphor, as this work demonstrates. After obtaining two expensive, commercially-produced life-sized porcelain replicas of leopards – the kind of kitsch often found in interior decorator’s shops – he then broke them into shards, which he placed within a pair of steel industrial containers. By entitling the work Zooid, he necessarily generates associations of the way zoos can curb animal behaviour, especially as the wiring of the containers suggests the bars of a cage. And by placing reminders of animal life within industrial containers, Cragg also communicates a point about the relationship of the natural world to industrialisation more generally. Naturally, in all this his attitude towards sculptural kitsch is made brutally clear.

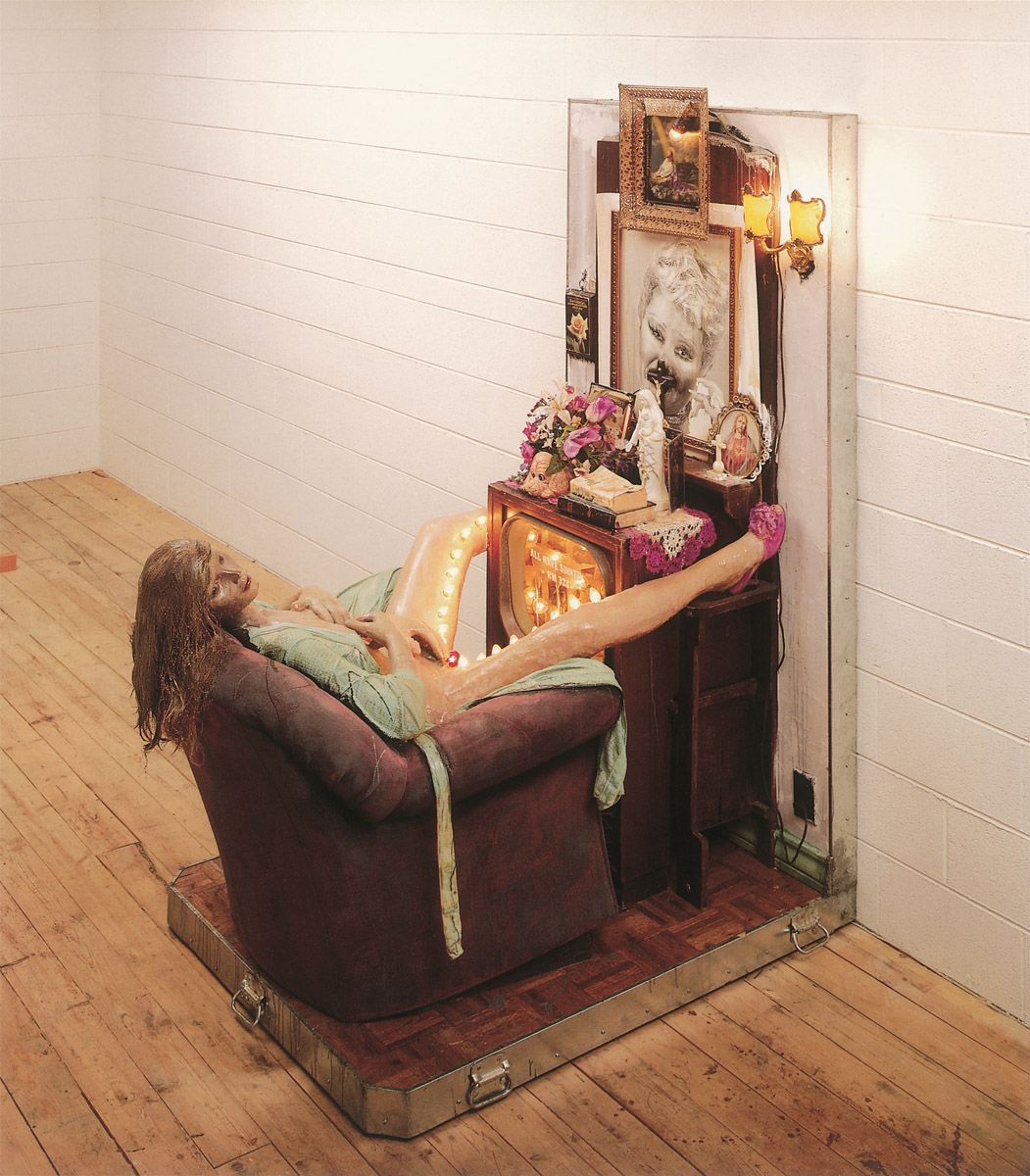

Ed Kienholz and Nancy Reddin Kienholz, All Have Sinned in Rm.323, 1992. Plaster cast, wig, clothing, slippers, stuffed chair, television, lights, photograph, dolls, artificial flowers, paint and polyester resin, 201. 3 x 106.7 x 165.1 cm. Collection of Nancy Reddin Kienholz, courtesy L.A. Louver Gallery, Venice, California.

Here is television viewing with a difference, as Kienholz and Reddin hit at three targets simultaneously: they equated tele-evangelism with masturbation; they attacked the utter humbug of many of those who preach over the airwaves; and they ridiculed religious kitsch.

Clearly, the key to the installation is the nauseatingly fake shrine which forms its centrepiece. At its heart is a large photograph of the American television evangelist and singer Tammy Faye Bakker. In the 1980s she and her then-husband, fellow-evangelist Jim Bakker, caused outrage when it emerged they were living hypocritically in enormously affluent style upon the proceeds of their television preaching, and that Jim Bakker had committed major fraud in order for them to do so. As a result he was eventually sentenced to forty-five years in prison (although that penalty was subsequently reduced to eight years on appeal). It might well be that Kienholz knew Frank Zappa’s 1988 song Jesus thinks you’re a jerk, which attacks such tele-evangelists, although the sculptor had always deprecated the hypocrisies of religion anyway. It is therefore unsurprising that he regarded Tammy Faye Bakker as representing everything false about Christianity in America. The girl lies back apparently sated, with her brightly lit legs straddling the television as though offering up her most private parts to it. On the box sits a small toy dog, its eyes agog at what it sees.