FIG 66. Oakwood plants. (a) Wood anemone (Anemone nemorosa); (b) wood-sorrel (Oxalis acetosella); (c) honeysuckle (Lonicera periclymenum); (d) common dog-violet (Viola riviniana).

THIS CHAPTER IS ABOUT THE WOODS that probably most of us first think of: oak, ash and beech woods on deep brown-earth soils of the lowlands, or on shallower soils over chalk and limestone, with abundant woodland flowers in the field-layer, and it includes most woody vegetation in wet places. However, the line between this chapter and the next is not sharp. There is intergradation and overlap, and some woods might equally well have found a home in either chapter.

Woods on deep mildly acid brown-earth soils throughout lowland Britain, and more locally in Ireland, are dominated by pedunculate oak, often with an understorey of hazel and scattered hawthorn. Less often, sessile oak is dominant. Silver birch may sometimes be prominent, and various other trees may occur, including holly, rowan, wild service-tree, wild cherry, ash, yew, hornbeam and small-leaved lime. Most of these occur as scattered individuals, but some can be locally dominant, for instance hornbeam and small-leaved lime. Under the trees, the most constant plants are bracken, brambles and honeysuckle (Fig. 66c), and ivy is prominent in places. Bluebell is the most constant of the field-layer herbs, often staging spectacular displays of blue in early May (Fig. 1). The two male-ferns (Dryopteris filix-mas and D. affinis agg.) and broad buckler-fern (D. dilatata) are locally prominent, as is creeping soft-grass (Holcus mollis), which forms an understorey to the bracken (Fig. 67). Many other characteristic woodland plants are more scattered, but when in flower in spring they add their own patches of colour to the woodland floor before the bracken unfurls its fronds. The most widespread include wood anemone (Fig. 66a), wood-sorrel (Fig. 66b), pignut (Conopodium majus) and common dog-violet (Fig. 66d). Mosses are seldom prominent, but Isothecium myosuroides (Fig. 89a) often forms a green zone around the bases of the trunks, and Kindbergia praelonga, Mnium hornum and the beautiful Thuidium tamariscinum are frequent on stumps or on the ground (Fig. 68).

FIG 66. Oakwood plants. (a) Wood anemone (Anemone nemorosa); (b) wood-sorrel (Oxalis acetosella); (c) honeysuckle (Lonicera periclymenum); (d) common dog-violet (Viola riviniana).

This Quercus robur–Pteridium aquilinum–Rubus fruticosus woodlandW10 is very variable. It is the heir to much of the wildwood, the forest that covered our islands before Neolithic man began forest clearance. Even before man was a significant influence, it must have varied from place to place with climate and soil. In the woods as we see them now, the effects of millennia of human activity are superimposed upon this underlying natural variation. Much coppice-with-standards woodland is essentially this community (Figs 69, 70). The tree-layer would have been subject to selection, often for pure oak (and may bear the signs of systematic and intensive management, often followed by neglect), and the neat regular understorey of hazel coppice is an obvious artefact. Where the main crop taken was small timber for charcoal and bark for tanning, as was often the case in the west, the oaks themselves were coppiced, leading to a wood of similar species-composition, but with little or no hazel, and of different appearance and structure. A ‘natural’ wood might be composed of much the same species, but would be different again, and an altogether more untidy affair.

FIG 67. Sessile oak with bluebells at the peak of their flowering season, with creeping soft-grass (Holcus mollis) and bracken; a classic mix (Woodhead 1906). Bulbarrow Hill, Dorset, May 1977.

On more calcareous soils we encounter a different kind of woodland. Oak may still be dominant, but it is usually accompanied by ash, and it may be completely replaced by that tree. Hazel is constant, and in many places hawthorn is too. Field maple is a widespread and characteristic constituent. Wych elm and sycamore are frequent and occasionally dominant – the first a long-standing native, the other introduced a few centuries ago. Other trees in smaller quantity or more locally prominent include hornbeam, small-leaved lime, silver birch, goat willow, aspen, elder (Sambucus nigra) and holly. This Fraxinus–Acer campestre–Mercurialis woodlandW8 is conspicuously rich in species (Fig. 71). The shrub-layer is enlivened by a group of five calcicolous shrubs, dogwood (Cornus sanguinea), spindle (Euonymus europaeus), wayfaring-tree (Viburnum lantana), buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica) and wild privet (Ligustrum vulgare) – and the more widely distributed blackthorn (Prunus spinosa) and guelder-rose (Viburnum opulus). The field-layer is rich too, in summer often dominated by a green carpet of dog’s mercury (Fig. 72a), but in spring often colourful with a profusion of woodland flowers: bluebells, primrose, ground-ivy (Glechoma hederacea), yellow archangel (Fig. 72c), lesser celandine, herb-robert (Geranium robertianum), lords-and-ladies (Arum maculatum) and ramsons (Allium ursinum). Later-flowering species include sanicle (Fig. 72b), enchanter’s nightshade (Circaea lutetiana), woodruff (Galium odoratum), wood avens (Geum urbanum) and stinking iris (Iris foetidissima) – with meadowsweet (Filipendula ulmaria), bugle (Ajuga reptans) and tufted hair-grass (Deschampsia cespitosa) in damper places. Ferns include hart’s-tongue (Phyllitis scolopendrium), hard shield-fern (Polystichum aculeatum, mainly N and W) and soft shield-fern (P. setiferum, mainly S). Three unspectacular but characteristic plants are wood-sedge (Carex sylvatica), false brome (Brachypodium sylvaticum) and wood dock (Rumex sanguineus). The mosses are generally more calcicole (Fig. 73). The oxlip (Fig. 72d) woods of eastern England belong here.

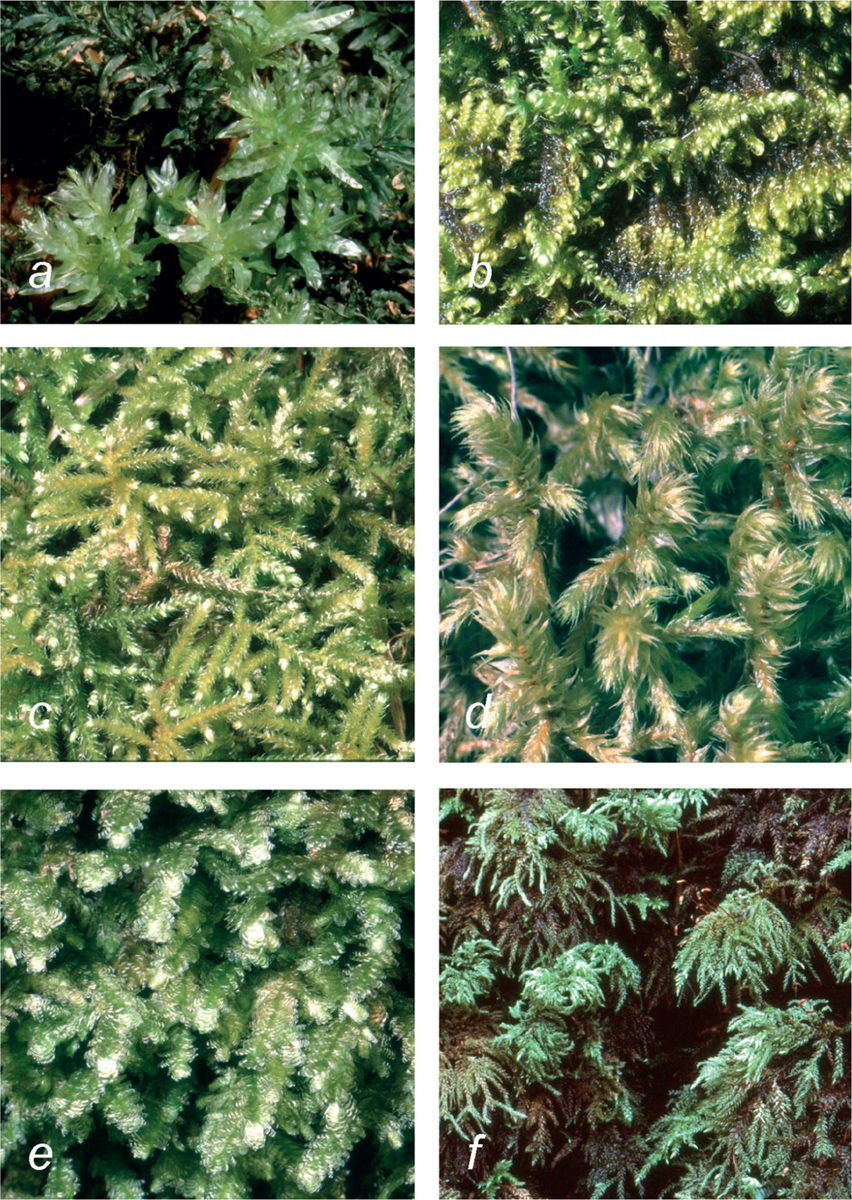

FIG 68. Mosses of oakwoods. (a) Mnium hornum often carpets banks and stumps; it produces big pendulous capsules, which mature in early spring. (b) Thuidium tamariscinum, a frequent and striking species on banks and the floor of the wood. (c) Kindbergia praelonga, common in many woodland situations. (d) Atrichum undulatum, on the ground, superficially like Mnium hornum, but with a band of green lamellae over the midribs of the leaves and very different cylindrical capsules.

FIG 69. Yellowham Wood, near Dorchester, April 1969. A traditional coppice-with-standards wood: pedunculate oak with an understorey of hazel. An area coppiced a year or two previously. The cut stools of hazel have started to re-grow; wood anemones and primroses in flower. Fig. 70 shows how much the hazel has grown five years later. See also Fig. 46.

FIG 70. Yellowham Wood, April 1974. The nearer part was coppiced six or seven years previously.

FIG 71. Small-leaved lime wood on Devonian limestone, Chudleigh Rocks, Devon, May 1972. Other woody species include wych elm, field maple, ash and hazel; field-layer dominated by ramsons (Allium ursinum).

FIG 72. Plants of base-rich woods. (a) Dog’s mercury (Mercurialis perennis); (b) sanicle (Sanicula europaea); (c) yellow archangel (Lamiastrum galeobdolon); (d) oxlip (Primula elatior).

FIG 73. Mosses of base-rich woods. (a) Plagiomnium undulatum; (b) Ctenidium molluscum; (c) Eurhynchium striatum; (d) Rhytidiadelphus triquetrus; (e) Neckera crispa; (f) Thamnobryum alopecurum.

This woodland has its origins in the wildwood of the more calcareous soils, on the chalk and the various older limestones in Britain, and partakes of the same kind of variation as the last, and has a similar history of use and management; coppice-with-standards examples are often encountered. Essentially the same kind of woodland, but lacking field maple and dog’s mercury (and some other species common in southern England), is scattered over the Carboniferous limestone of Ireland, where it has been called (following Braun-Blanquet & Tüxen) the ‘Corylo-Fraxinetum’ (Fig. 74). In Ireland many examples are dominated by hazel alone, notably the hazel scrubs of the Burren in Co. Clare, many of which are species-rich woods in all but their lack of ‘trees’. There is little in the field-layer to differentiate them from ash-dominated sites.

FIG 74. Ash–hazel wood (Corylo-Fraxinetum) with birch and rowan on a rocky limestone slope, Poulavallan, Burren, Co. Clare, July 1959. The field-layer includes wild strawberry, barren strawberry, wood avens, ivy, yellow pimpernel, wood-sorrel, hart’s-tongue, hard shield-fern, bush vetch and common dog-violet. Bryophytes include Eurhynchium striatum, Loeskeobryum brevirostre, Plagiochila asplenioides, Plagiomnium undulatum, Rhytidiadelphus triquetrus and Thuidium tamariscinum.

Beech is native with us only in southern England and adjacent parts of Wales, where it dominates woodland communities parallel to those just considered dominated by oak. Extensive beechwoods on the deep, acid brown-earth soils developed on superficial deposits over the chalk of the Chilterns, and comparable soils from the North Downs to the New Forest, and the Cotswolds to the Carboniferous limestone of South Wales. Beech casts a deeper shade than oak, and as one consequence of this these ‘plateau beechwoods’ (Fagus sylvatica–Rubus fruticosus woodlandW14, Fig. 75) show significant difference from their oak-dominated counterparts. They lack a shrub-layer (there is very little hazel), bracken and honeysuckle are much less common and do less well, and bluebell is infrequent. These beechwoods are not floristically exciting places, but they are magnificent in their own right, and historically they have provided the timber on which the Chiltern furniture industry was based: Tansley (1939) included a photograph of ‘chair bodgers’ at work in the woods. The canopy is usually almost pure beech, though it may include a proportion of sessile oak, and often there is a sparse or denser subsidiary tier of holly. Other trees that occur occasionally are whitebeam, wild cherry, yew and sycamore. The only constant constituent in the field-layer is bramble, which may cover half the woodland floor, or be only a wispy cover, depending on shade and root-competition with the trees, and grazing. The only other species that is frequent and attains substantial cover is bracken. Otherwise there is only a sparse ground flora, of which the main ingredients are wood-sorrel, occasional yellow archangel and woodruff, a few grasses – most notably wood millet (Milium effusum), wood melick (Melica uniflora) and creeping soft-grass – and the mosses Mnium hornum and Polytrichastrum formosum.

FIG 75. Plateau beech wood after the great storm of 15/16 October 1987. Box Hill, Surrey, November 1987. Patches of low bramble on the floor of the wood; sparse shrub-layer of holly and box. Occasional catastrophes – storm, drought, fire and flood – are a part of life for plant communities; the only certainty is that it will happen again – but when?

The beechwoods of the calcareous rendzina soils of the chalk escarpments are much better known, thanks to Gilbert White’s description of the beech ‘hanger’ in The Natural History of Selborne, and to the fact that they are home to some odd and attractive rare plants. The beeches on these thin, poor calcareous soils are not as well grown as the trees on the deeper and richer brown-earth soils we have just considered, but they still cast a deep shade, and the ground beneath them is comparably bare. Beech is usually dominant almost to the exclusion of other trees in this Fagus sylvatica–Mercurialis perennis woodlandW12, with just the occasional ash or sycamore, and less often oak. There is often no shrub-layer, or there may be a scatter of hazel, hawthorn, field maple, elder, spindle, wayfaring-tree, dogwood and holly. The character of the field-layer mainly reflects the character of the soil. On the deeper soils, dog’s mercury generally forms a light cover, with a sparser version of the ground flora of ash–oak-dominated woodland on similar calcareous soils, often with a good deal of bramble. On thinner and chalkier soils there is more bare ground. Here, sanicle rivals or exceeds dog’s mercury in a very characteristic field-layer, with tall slender plants of wall lettuce (Mycelis muralis) in the deep shade, wood melick and wood meadow-grass (Poa nemoralis); black bryony (Tamus communis) and hairy brome (Bromopsis ramosa) are also frequent. A very characteristic plant here is the white helleborine orchid (Fig. 76). This community provides a habitat for some notable rarities, including long-leaved helleborine (Cephalanthera longifolia), red helleborine (C. rubra), narrow-lipped helleborine (Epipactis leptochila), bird’s-nest orchid (Neottia nidus-avis), yellow bird’s-nest (Monotropa hypopitys), wood barley (Hordelymus europaeus) and green hound’s-tongue (Cynoglossum germanicum). On thin dry soils on southerly slopes, yew can become more constant and form a shrub-layer under the beech; on Box Hill in Surrey, box (Buxus sempervirens) can behave similarly. This creates deep shade and, with the dryness of the soil, the ground flora becomes very sparse.

FIG 76. White helleborine (Cephalanthera damasonium), a very characteristic plant of escarpment beechwoods on the chalk. Note the otherwise rather sparse field layer. Hambledon Hill, Dorset, June 1970.

Beech has been very widely planted in both Britain and Ireland, and regenerates freely far outside the range it had reached naturally. With most of the other species already there, it has carried what are often to all intents and purposes the last two communities with it to its new-found territory.

Yew locally forms woods on thin soils over the southern English chalk, most typically on the steep slopes of the sides and heads of dry valleys, but always with a preference for a south- to west-facing aspectW13. Yew-woods are rather frequent along the North Downs (where the main escarpment is south-facing), at the western end of the South Downs in West Sussex (Fig. 77) and Hampshire, and at the southwestern end of the Chilterns; there is a nice outlying example on the south side of Hambledon Hill in Dorset. Farther north and west, there are patches of yew wood in the Cotswolds and on Carboniferous limestone in the Wye Valley and northern England, and there is a notable Irish yew wood on the Carboniferous limestone of the Muckross peninsula at Killarney.

On the chalk of southern England, yew forms a dense canopy, alone or with a scatter of whitebeams and the occasional ash. Typically the shade is so dense that almost nothing grows beneath the canopy beyond a few tree and shrub seedlings. Whitebeam is an opportunist invader of gaps in the yew canopy, as is elder, the most frequent shrub. Where the canopy is a little more open, a scatter of shrubs and a thin field-layer can become established. A sparse growth of spindle, wild privet and dogwood accompany somewhat more frequent elder. The field-layer consists mostly of a patchy cover of dog’s mercury. The slightly ‘weedy’ tone set by the elder is echoed by occasional patches of stinging nettles; an uncommon ruderal that occurs occasionally in this situation is deadly nightshade (Atropa belladonna). On Carboniferous limestone in the Wye Valley and the north of England, yew is seldom as uncompromisingly dominant as it is on the chalk, and the field-layer of yew wood is an impoverished version of that of the neighbouring ashwoods.

FIG 77. Kingley Vale, West Sussex, June 1985. General view of the lower part of the yew wood; escarpment beechwood beyond. Inside the yew wood the shade is so dense that practically nothing grows under the trees. Hawthorn in flower in the foreground.

The Killarney yew wood is on limestone pavement (Fig. 78). The higher and drier areas, with only skeletal soils, are dominated by yew with little else apart from scattered holly and occasional patches of hazel. Wherever there is some accumulation of soil, taller and more mixed woodland has been able to develop, with ash as a substantial component of the canopy, and an open shrub-layer of hazel, with some spindle. Bramble, hawthorn, ivy, honeysuckle and holly are scattered throughout. Because the ground is so rocky, herbs needing any substantial depth of soil are sparse: false brome is common; other species include sanicle, hart’s-tongue and soft shield-fern. The limestone rocks are thickly covered with bryophytes including Thamnobryum alopecurum, Eurhynchium striatum, Thuidium tamariscinum, Rhytidiadelphus triquetrus, Loeskeobryum brevirostre, Neckera complanata, Ctenidium molluscum, Tortella tortuosa and Marchesinia mackaii.

FIG 78. Yew wood on Carboniferous limestone, Muckross peninsula, Killarney, Co. Kerry. Here yew is co-dominant with ash, there is a sparse field layer, and the limestone rocks are covered with bryophytes, mostly Thamnobryum alopecurum.

In a few places in southern England box forms woods on steep dry south-facing slopes in a similar way to yew. The largest and best known of these is at Box Hill in Surrey, where the River Mole has cut a steep cliff in the chalk of the North Downs (Fig. 79). The evergreen box casts a deep shade, and this together with the steepness of the slope and the dryness of the soil means that little can grow beneath the canopy. There was formerly a box wood at Boxley near Maidstone in Kent, recorded by John Ray in 1695. Box is also plentiful and locally forms dense scrub at Ellesborough Warren near Wendover in the Chilterns. The box wood at Boxwell Court, west of Tetbury in the Cotswolds, is known to have been in existence since at least the thirteenth century. It covers 5.3 ha on a steep southwest-facing limestone slope. Compartments have been regularly coppiced. Box wood is prized for its hardness, light colour and close uniform grain, and the wood brought in a large income to the Huntley family, and no doubt to the Abbots of Gloucester before them. An area cut over during the First World War had regenerated by the 1970s, but still with traveller’s-joy (Clematis vitalba) among the box trees. On a second area, cutting in 1971 was followed by profuse growth of rosebay willowherb (Chamerion angustifolium), nettles and elder – and the odd plant of henbane (Hyoscyamus niger) – amongst the regenerating box, all destined to be shaded out as the trees grew up.

FIG 79. Box Hill, Surrey, July 1958. The box-wood occupies the steep southwest-facing chalk slope cut by a meander of the River Mole. The high-crowned trees are beech; the trees with grey-green foliage are whitebeams.

Box has been widely planted over the centuries, and does well in our climate, so it is impossible to say with certainty where it is native. ‘Box’ place-names on the chalk and Jurassic limestones – as at Box in Wiltshire and Gloucestershire, Boxford in Berkshire and Suffolk, Boxted in Suffolk and Boxgrove in Sussex – suggest long historical associations with this tree, which may have been more widely indigenous. Other ‘Box’ and ‘Bux’ place-names seem to have other origins (Eckwall 1960).

In upland country the woods gradually change in character. The oaks (here most often Quercus petraea) are less well grown, and birches (Betula pendula and B. pubescens) become more frequent and may be dominant. Hazel, hawthorn and honeysuckle are less common, and hornbeam and small-leaved lime are virtually absent from the upland woods. Bracken remains prominent, but brambles are much less so. The field-layer is more grassy, perhaps partly reflecting the fact that these upland woods are more often open to grazing. Sweet vernal-grass (Anthoxanthum odoratum), common bent (Agrostis capillaris), wavy hair-grass (Deschampsia flexuosa) and creeping soft-grass (Holcus mollis) are constant or nearly so, and a group of large mosses are common, including Rhytidiadelphus squarrosus and R. triquetrus, Pseudoscleropodium purum, Thuidium tamariscinum, Hylocomium splendens, Pleurozium schreberi and Dicranum majus. The more frequent herbs on the woodland floor include wood-sorrel, common dog-violet, heath bedstraw (Galium saxatile), tormentil (Potentilla erecta), bluebell, germander speedwell (Veronica chamaedrys), wood anemone, primrose, hairy wood-rush (Luzula pilosa) and pignut; chickweed-wintergreen (Trientalis europaea) is particularly characteristic of stands of this community in the eastern Highlands. Ferns (other than bracken) are usually not prominent; they include scaly male-fern (Dryopteris affinis), broad buckler-fern and hard fern (Blechnum spicant)W11.

This upland Quercus petraea–Betula pubescens–Oxalis acetosella woodland (Fig. 80) is very widespread in the north and west of Britain (some woods on high ‘plateau gravels’ in the southeast arguably belong here), and could be matched in Ireland. It is a prime example of a woodland in which the tree-canopy can change with little effect on the character of the vegetation on the ground, so it embraces woods dominated by both the oak species, and many woods dominated by birch (usually Betula pubescens, but sometimes B. pendula), and even hazel scrub in Skye and elsewhere in western Scotland (Birks 1973).

The northern and upland ashwoods on limestone also differ from their lowland counterparts, the ash–field-maple–dog’s-mercury woods, but (perhaps because suitable habitats for them are more fragmented) they do not present as coherent a picture as the oak–birch–wood-sorrel woods of more acid soils. Overall, they lack field maple, the calcicolous shrubs of the south, and some other lowland species. Conversely, rowan and downy birch are commoner and bird cherry occurs more widely. In the field-layer, wood-sorrel, common dog-violet, male-fern and the mosses Thuidium tamariscinum, Plagiomnium undulatum and Eurhynchium striatum are much more conspicuous than they are in the lowland woods. Northern species occurring in some of the damper of these upland ashwoods in northern England and Scotland include wood crane’s-bill (Geranium sylvaticum), globeflower (Trollius europaeus), marsh hawk’s-beard (Crepis paludosa), melancholy thistle (Cirsium heterophyllum) and various lady’s-mantles (Alchemilla spp.)W9.

FIG 80. Upland oak (Quercus robur) wood, near Shaugh Prior, Dartmoor, Devon. The grassy field-layer is dominated by sweet vernal-grass, with some creeping soft-grass, bluebells, bracken, great wood-rush and abundant wood-sorrel.

This ash–rowan–dog’s-mercury woodland has a northern and western distribution on limestone (or other base-rich rocks) from upland Wales and northern England to the north of Scotland. The woods on the steep sides of the high Yorkshire Dales (closely matched by some Irish woods) are in general this community, by contrast with the Peak District woods (e.g. in Dovedale, and along the Via Gellia), which generally have a decidedly lowland character. Some of these Yorkshire Dales woods are on limestone pavement. Colt Park Wood near Ribblehead is an extreme example (Fig. 81). It occupies a strip of deeply dissected limestone pavement above a cliff a few metres high in the stepped limestone landscape. The flattish blocks of limestone forming the surface (‘clints’) are separated by deep fissures (‘grikes’), many wide enough to hold a sheep (occasionally sheep are trapped in the grikes and perish miserably if not retrieved in time). The clints bear a patchy thin soil, but many plants, including the trees, are rooted in the soil at the bottom of the grikes, or in crevices in the limestone rock. Colt Park Wood has a light tree-canopy, mainly of ash, with hazel, hawthorn, bird cherry, blackthorn and wych elm. The ground flora is rich in species to match the diversity of habitat; among the more notable plants are alpine cinquefoil (Potentilla crantzii), northern bedstraw (Galium boreale) and angular Solomon’s-seal (Polygonatum odoratum) rooted on the clints, and baneberry (Fig. 82a), globeflower, northern (Crepis mollis) and marsh hawk’s-beards, wood crane’s-bill and melancholy thistle in the grikes. The nearby limestone ravine of Ling Gill lacks the clints and grikes, but has a generally similar flora.

FIG 81. Colt Park Wood, Ribblehead, North Yorkshire, July 1966. Farther back from the cliff edge the vegetation often hides the clints and grikes of the Carboniferous limestone rock.

Limestone pavements are complex mosaics of diverse habitats, and have correspondingly diverse vegetation (Fig. 83). The grikes supply many of the ingredients of a woodland environment: shelter from drying winds, and shade, which becomes deeper with the depth of the grike. Many bare limestone pavements have a woodland flora dominated by dog’s mercury at the bottom of the grikes, with ferns – hard shield-fern (Fig. 82c), male-fern, hart’s-tongue and wall-rue, maidenhair and green spleenworts (Asplenium ruta-muraria, A. trichomanes, A. viride, Fig. 82d) – and other plants rooted deep in the grikes, or in crevices on their sides. Where there is a soil cover on the clints, it can carry a grassland or heathy flora depending on its thickness. Samples from limestone pavements in the Burren (where dog’s mercury is very rare) yielded a long list of grassland species; woodland was represented by false brome, ivy, tutsan (Hypericum androsaemum), wood-sorrel and sanicle, scrub fringes by bloody crane’s-bill (Fig. 82b) – and seedlings or saplings of all the woody ingredients of typical Burren limestone scrub or woodland. The grikes provide a congenial habitat for the establishment of tree and shrub seedlings, but if the pavement is grazed these are browsed level with the clints and cannot grow to maturity. If grazing is relaxed that can quickly alter. Scar Close on the west side of Ingleborough is ungrazed, and has changed within the last half-century from an almost bare expanse of limestone pavement with scattered trees to a no-less-interesting site with abundant trees and some extensive patches of open ash–rowan–dog’s-mercury woodland.

FIG 82. Plants of limestone pavement. (a) Baneberry (Actaea spicata); (b) bloody crane’s-bill (Geranium sanguineum); (c) hard shield-fern (Polystichum aculeatum); (d) green spleenwort (Asplenium viride).

FIG 83. Scar Close, Ingleborough, North Yorkshire, July 1964. Limestone pavement, with and without a soil cover; scattered ash trees rooted in the grikes, which have since grown up into patches of woodland.

There are some woods in Scotland that represent the northern fringe of ashwood in Britain. John Birks described ashwoods from Durness limestone in Skye, which are clearly the same kind of vegetation as the upland ashwoods of the Yorkshire Dales (false brome seems to increase progressively northwards). However, the distinctive tall herbs of the grike flora at Colt Park Wood are missing, and appear in another community, the ‘Betula pubescens–Cirsium heterophyllum association’ at low altitudes on inaccessible ledges in damp wooded ravines on basic rocks, dominated by birch but in which ash also occurs (Birks 1973). Maybe there is a lost woodland type here, of which we see a ghost in the traditional flowery hay meadows of the north of England, intergrading and locally forming mosaics with upland ashwood. We may visualise it dominated by downy birch with ash, willows and bird cherry, with a tall-herb field-layer, something like the little ‘Globeflower Wood’ near Malham Tarn. There are such woods in Scandinavia, and we have the ingredients for them in Britain.

FIG 84. Rassal ashwood, above Loch Kishorn, Wester Ross, June 1981. Open to grazing, with a grassy field-layer and bracken; mosses covering the limestone rocks.

Rassal ashwood, which lies on an outcrop of Durness limestone sloping gently westwards at about 300 m above Loch Kishorn, is the northernmost substantial ashwood in Britain. It was open to grazing when it was declared a National Nature Reserve in 1956; the limestone rocks were thickly covered with mosses, and the less rocky parts were grassy with a patchy cover of bracken. After the wood became a nature reserve some areas were fenced; the two photographs taken in 1981 (Figs 84, 85) show the remarkable contrast in vegetation between grazed and ungrazed areas. The ash trees, some of them large, form a dense canopy in places but in others are more open. Hazel is abundant, with occasional downy birch, goat willow and rowan, and some hawthorn and blackthorn scrub. The grazed, grassy parts are dominated by sheep’s fescue (Festuca ovina) and common bent with crested dog’s-tail (Cynosurus cristatus) and tufted hair-grass. Only a few woodland plants were apparent in the crevices between the rocks (e.g. false brome, sanicle, primrose) but surprisingly luxuriant woodland vegetation (including wood avens, meadowsweet and creeping buttercup, Ranunculus repens) grew up when grazing was excluded.

FIG 85. Rassal ashwood. Ungrazed exclosure, with luxuriant field-layer including male-fern, creeping buttercup and meadowsweet. June 1981.

Patches and tracts of country dominated by sallows are common in both countries. In Britain, Rodwell (1991a) divides the wet sallow-dominated vegetation widely scattered over lowland England and Wales, usually on wet mineral soils (‘Salix cinerea–Galium palustre woodland’)W1, from the fen carr of East Anglia and the Shropshire–Cheshire plain, usually on peat (‘Salix cinerea–Betula pubescens–Phragmites australis woodland’)W2. Both are exceedingly variable, and not well characterised. There is all-too-little good descriptive information about sallow scrub in Britain. It is often difficult and uncomfortable to work in, and not a superficially attractive habitat. The Sphagnum sub-community of the East Anglian fen carr would probably be better united with the birchwoods on peat (Chapter 7), leaving the Alnus–Filipendula sub-community (mainly of eutrophic peats) grouped with the widespread Salix cinerea–Galium palustre woodland and the Irish sallow sites. In Ireland sallow scrub grows mainly on alluvial soils, and seems to be better characterised, with constant sallow, near-constant alder, marsh bedstraw (Galium palustre), creeping bent (Agrostis stolonifera), and the mosses Kindbergia praelonga and Calliergonella cuspidata. There is a long list of frequent species, including ash, purple-loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria), creeping buttercup, yellow iris (Iris pseudacorus), marsh bedstraw and water mint (Mentha aquatica) (Kelly & Iremonger 1997).

The abundant supply of nutrients brought in by silting makes riverside habitats fertile places, which favours plants with ruderal tendencies such as nettles, elder, reed canary-grass (Phalaris arundinacea) and great willowherb (Epilobium hirsutum). Wet woods along streams and riversides and around eutrophic lakes can be dominated interchangeably by sallow, alder, various tree willows and osiers, for which ‘Alnus glutinosa–Urtica dioica woodland’W6 and ‘Salicetum albo-fragilis’ are equally misnomers, because neither alder nor tree-willows are necessarily present, and large areas of eutrophic vegetation of this kind are dominated by sallow. This is the nearest we have in Britain and Ireland to the floodplain woodland that lines many central-European rivers. Frequent species include crack-willow, sallow, alder, elder, cleavers (Galium aparine), bittersweet (Solanum dulcamara), bramble and hemlock water-dropwort (Oenanthe crocata). Meadowsweet, greater and lesser pond-sedges (Carex riparia and C. acutiformis), yellow iris, common valerian (Valeriana officinalis), cuckooflower (Cardamine pratensis), marsh-marigold (Caltha palustris), wild angelica (Angelica sylvestris), gypsywort (Lycopus europaeus) and opposite-leaved golden-saxifrage (Chrysosplenium oppositifolium) lend interest and colour to this otherwise rather forbidding community.

In northern England and Scotland a distinctive fen carr occurs, often dominated by bay willow (Salix pentandra – a beautiful species), sometimes other northern Salix species, and grey (common) sallowW3. This is a well-characterised community with a long list of constant or near-constant species, including cuckooflower, marsh bedstraw, marsh-marigold, meadowsweet, bottle sedge (Carex rostrata), water avens (Geum rivale) and frequent bogbean (Menyanthes trifoliata), marsh hawk’s-beard, common valerian, water mint and marsh cinquefoil (Potentilla palustris), and bryophytes including Calliergonella cuspidata, Rhizomnium punctatum and Climacium dendroides. Bay willow occurs in Ireland, especially in the north, but never seems to become prominent in carr.

Grey sallow commonly forms extensive stands in largely stagnant sites. By contrast, alder usually grows in places where there is some water flow, either close to rivers or streams (alder is a common riverbank tree), at spring-lines, or in valleys with water flow through the subsoil.

A very characteristic type of wet woodland is dominated by alder, with variable amounts of silver birch, sallow and ash, with greater tussock-sedge (Carex paniculata) dominant in the understoreyW5. This is a variable but striking and rather species-rich wet woodland with few constants but a long list of species that are frequent wherever it occurs. These include marsh bedstraw, bittersweet, cuckooflower, marsh thistle (Cirsium palustre), water mint, stinging nettle, yellow iris and marsh valerian (Valeriana dioica); this is a habitat of the beautiful moss Hookeria lucens. Alder buckthorn (Frangula alnus, a food-plant of the brimstone butterfly) is common in some stands, and royal fern (Osmunda regalis) occurs occasionally. This community is widely scattered over England and Wales, in habitats ranging from some of the Norfolk Broads and the banks of Broadland rivers, to spring-lines on the East Devon hills (Fig. 86) and seepage tracks through New Forest and Dorset valley bogs. There are a few sites in Scotland, but it is apparently rare in Ireland.

FIG 86. Alder–great tussock-sedge (Alnus glutinosa–Carex paniculata) woodland at the springline between permeable Cretaceous sands and gravels capping the hill, and the Permian marls beneath. Pen Hill, Sidbury, Devon, June 1977.

Ireland still has a surviving fragment of the Geragh, near Macroom in Co. Cork, a unique labyrinth of braided river channels and islets clothed in tangled woodland, which was largely destroyed by a hydroelectric scheme in the 1950s. Trees include sessile oak and ash up to 15–18 m high, with alder, birch, hazel, hawthorn, grey sallow, goat willow, holly, bird cherry, spindle and guelder-rose. The ground flora includes many plants of base-rich woodland; patches of ramsons are conspicuous, and in the wetter places the widespread woodland herbs give way to patches of e.g. marsh-marigold, opposite-leaved golden-saxifrage, water mint and water ragwort (Senecio aquaticus). Many of the island margins are conspicuously populated with hemlock water-dropwort and royal fern (White 1985).

In hilly parts of both Britain and Ireland, flushes or wet gullies in otherwise well-drained oakwoods on mildly acid brown-earth soils are often occupied by patches of a distinctive wet woodland in which alder is often dominant, usually accompanied by some ash, hazel and occasionally birchW7. Meadowsweet is usually conspicuous in the field-layer, with creeping buttercup and other plants of wet places such as opposite-leaved golden-saxifrage, wild angelica, marsh thistle, tufted hair-grass, common valerian and soft-rush (Juncus effusus); two species particularly characteristic of the habitat are yellow pimpernel (Lysimachia nemorum) and remote sedge (Carex remota); other sedges that find this a congenial habitat are pendulous sedge (Carex pendula, a stately plant) and smooth-stalked sedge (Carex laevigata). Bryophytes are common: among the more frequent species are the mosses Kindbergia praelonga, Brachythecium rutabulum, Atrichum undulatum, Plagiomnium undulatum and Rhizomnium punctatum, and the liverworts Pellia epiphylla and Lophocolea cuspidata. Striking but rarer species that occur in this habitat are the moss Hookeria lucens, which has broad flat leaves and cells so big they can be seen with the naked eye, and the beautifully fringed leafy liverwort Trichocolea tomentella.

Most of the common woodland flowers of the oakwood are still present here, and this kind of woodland is often rather species-rich. However, its composition is variable. In the more eutrophic examples (a minority), elder is rather frequent, nettles and cleavers are common, and opposite-leaved golden-saxifrage covers a substantial fraction of the ground. In the wetter centre of the flush meadowsweet and its wet-ground associates are most prominent; occasionally (in both islands) great horsetail (Equisetum telmateia) can become dominant in this situation, perhaps always where the percolating water is highly calcareous. Tufted hair-grass dominates the field-layer on ground that is damp rather than wet.