FIG 224. The extent of heathland between Dorchester and the River Avon in 1811, from the first edition of the Ordnance Survey One-Inch map, and in 1960. Re-drawn from Moore (1962).

THIS CHAPTER IS ABOUT the land dominated by heathers and other heath shrubs, and the (mostly poor) grasslands that can replace heathy vegetation under grazing. Traditionally, in southeast England any land not fit for cultivation was regarded as ‘heath’; in other regions ‘moor’ carried much the same meaning. Often these were areas on poor, infertile, acid soils dominated by dark expanses of heather giving rise to such names as Blackdown, Blackheath, Blackhill and Blackmoor. These areas were often ‘commons’, they were generally owned by the landowner, but his tenants (or local inhabitants) had ‘common rights’, which frequently included grazing.

The heaths of lowland England mark out the areas of poor, sandy or gravelly but above all acid and infertile, often podzolic, soils. They intergrade westwards with the exposed coastal heaths of southwest England, Wales and Ireland. The heather moors of hills on the harder rocks of the north and west share many species with the lowland heaths but are rather different in both flora and ecology, and in traditional land use.

The story of the English lowland heaths over the past half-century is an object-lesson for conservation. Fifty or sixty years ago much of the attention of naturalists (and biologists generally) was fixed on ‘rare’ or ‘interesting’ species or habitats. Heaths qualified for attention on neither ground; they were seen as a widespread and common vegetation type that we need not worry about. Norman Moore in 1962 drew attention to the alarming rate of decline in the heaths of southeast Dorset (Fig. 214). In 1811, the first edition of the Ordnance Survey showed heaths covering an area of about 30,000 ha, roughly matching the area of heathland soils shown on the Soil Survey 1:250,000 map of 1983. This was well within living memory for Thomas Hardy (1840–1928) as a model for ‘Egdon Heath’ when he was writing his Wessex novels. The varied fortunes of farming in the nineteenth century left the overall pattern not much changed, with the major exception of the growth of Bournemouth, which did not exist in 1811. Nevertheless in 1891 the map still showed some 23,000 ha of heath. By 1934 the heathland was more fragmented, and its total area had declined to 18,000 ha. The situation when I first knew the area in 1946 was not greatly different, but heath declined very rapidly in the post-war years, and by 1960 only some 10,000 ha were left. Much of that has disappeared in the last 50 years, and the most substantial blocks of heathland that remain are now in nature reserves or army training areas.

FIG 224. The extent of heathland between Dorchester and the River Avon in 1811, from the first edition of the Ordnance Survey One-Inch map, and in 1960. Re-drawn from Moore (1962).

The story has been much the same on the once-extensive heaths of the Cenozoic sands and gravels in Surrey and adjacent northeast Hampshire and Berkshire. These heaths have been particularly hard-hit by the sprawling urban development southwest of London. The rich and diverse heathland on similar (but more varied) geology and soils in the New Forest has had better planning protection and has fared better, and it is now a National Park. The Lower Greensand at the west end of the Weald from near Dorking and Farnham in the north, southwards to Petersfield and along the foot of the South Downs to Storrington, still bears substantial areas of heath including Thursley Common and Hindhead. Heaths occur on various other substrata, including the Wealden sand of Ashdown Forest, Permo-Triassic sands and pebble beds in east Devon, but most widely on the ‘clay-with-flints’ overlying the chalk, and other superficial deposits of flat hill-tops, or on sandy glacial drift.

The heaths of lowland England intergrade in a way that defies easy classification. Most dry heaths within 100 km of London are dominated by common heather (Calluna vulgaris), with variable proportions of bell heather (Erica cinerea) and at least scattered low patches of dwarf gorse (Ulex minor)H2. Wavy hair-grass (Deschampsia flexuosa) is often present, but the only other vascular plants that occur at all commonly in dry heaths are bracken (mostly at the margins of the heath or where there has been disturbance in the past) and, very locally, bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus). The other noticeable ingredients in the community, especially in the years following a heath fire, are a suite of calcifuge mosses, including Ceratodon purpureus, Polytrichum juniperinum, Dicranum scoparium and Hypnum jutlandicum, and lichens of the genus Cladonia.

Heath can grow on thin superficial deposits over chalk. Before the widespread ploughing of the 1950s and 1960s, and in the heyday of rabbits, these sites were more widespread and often closely grazed, and were very striking for their mixture of calcicole and calcifuge plants. Tansley (1939) could write: ‘Thus is developed the beginnings of a vegetation which has been called chalk heath, because it is marked by a mixture of calcicolous plants rooting in calcareous soil with indifferent and calcifuge heath plants rooting in the acid surface soil. Large areas of plateau and dip slope are dominated by Calluna or Erica cinerea, accompanied by such characteristic southern heath plants as Ulex minor.’ Most of the ‘large areas of plateau and dip slope’ are now under the plough, and with the relaxation of grazing, the fragments of ‘chalk heath’ that remain have realised Tansley’s supposition that ‘… “chalk heaths” of the kind described develop into more typical heaths by further leaching and the accumulation of acid humus at the surface.’

Dwarf gorse is a low-growing subshrub (Fig. 225a), rather strictly confined to heathland. It has more delicate spines than common gorse (Ulex europaeus), smaller flowers, much less hairy buds and calyces, and flowers in late summer. It is concentrated in southeast England from Surrey, Berkshire and the High Weald to the heaths of southeast Dorset, with outlying localities in Lincolnshire and Nottinghamshire and a northern outpost near Carlisle. Common gorse is an altogether more robust shrub, up to a metre or two high, with stiff sharp spines; it is common on heaths along road and track sides and in disturbed places, but also grows in scrub and open woodland on acid soils. It starts flowering in autumn, continues in mild spells through the winter, has its main flowering period from March to May, and some flowers hang on into early summer. It is common throughout Britain and Ireland.

FIG 225. Heath and moorland subshrubs: (a) dwarf gorse (Ulex minor); (b) Dorset heath (Erica ciliaris); (c) Cornish heath (Erica vagans); (d) Mackay’s heath (Erica mackaiana); (e) St Dabeoc’s heath (Daboecia cantabrica); (f) Cowberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea).

From the southwest fringes of the Surrey–Berkshire heaths to the New Forest and the heaths of southeast Dorset, two other major players join the dry-heath community, bristle bent (Agrostis curtisii) and purple moor-grass (Molinia caerulea). Bristle bent has a compact distribution in south and southwest England and south Wales, within which it is abundant on almost every heath. It is a very distinctive grass, forming tight tufts of fine, slightly glaucous leaves amongst the heath subshrubs, quite unlike our other species of Agrostis. Molinia is a versatile grass we have already encountered in fen meadows (Chapter 14) and blanket bogs (Chapter 15). On the heaths of the New Forest–Poole Harbour area, the predominant Ulex minor–Agrostis curtisii heathM3 is dominated by an intimate mixture of varying quantities of six species: heather, bell heather, cross-leaved heath (Erica tetralix), dwarf gorse, bristle bent and Molinia. In the Poole Harbour area these six are sometimes joined by Dorset heath (E. ciliaris, Fig. 225b), which is abundant across the Channel in the heaths of Brittany. Apart from that, the only other frequent vascular plants are tormentil (Potentilla erecta), heath milkwort (Polygala serpyllifolia) and the ubiquitous common gorse and bracken. Mosses and lichens are sometimes prominent, including Hypnum jutlandicum, Campylopus brevipilus, Cladonia portentosa (Fig. 235e), C. coccifera (Fig. 235f) and C. crispata. In sharply drained and exposed places, Molinia, cross-leaved heath and even bristle bent may drop out, leaving an impoverished dry Calluna–Erica cinerea heath. Conversely, with increasing wetness of the soil, bell heather and bristle bent drop out at the transition to wet heath – but that is a story that will be taken up later.

West of Dorchester, dwarf gorse gives way remarkably suddenly and completely to a second late-summer-flowering species, western gorse (Ulex gallii). These two species were much confused in the past, because while their most obvious differences are in size, they are both very plastic to variations in soil and exposure. They have different chromosome numbers (dwarf, 2n = 32: western, 2n = 64) and can usually be reliably told apart by the smaller flower parts of dwarf gorse (the calyces persist until well into winter).

FIG 226. ‘Six-species heath’ (Ulex gallii–Agrostis curtisii heath) on Triassic pebble beds, Aylesbeare Common, Devon, September 1987.

Heaths on the clay-with-flints and other superficial deposits that cap the chalk and the older Jurassic and Triassic rocks of west Dorset and east Devon are dominated by the same six species as the Ulex minor–Agrostis curtisii heath, but with western gorse substituted for dwarf gorse. This six-species Ulex gallii–Agrostis curtisii heathH4 is the common dry heathland of the Southwest Peninsula, from west Dorset and the coast of south Wales to Cornwall (Fig. 216). It is more widely distributed, more variable and often richer in species than its more eastern counterpart. Tormentil is near-constant, and heath milkwort is usually present but easily overlooked. Mosses (e.g. Dicranum scoparium, Hypnum jutlandicum) and lichens (e.g. Cladonia portentosa, C. floerkeana, C. coccifera, C. chlorophaea) can be prominent, especially a few years after burning.

In southwest England the Ulex gallii–Agrostis curtisii heath comes into contact with other heath and moorland types, and intergrades with them. Where it grows on thin superficial deposits over limestone, it can acquire an admixture of deep-rooted calcicole species. On the upland areas of the southwest, especially Exmoor, Dartmoor and Bodmin Moor, it meets upland heather-moor and hill grasslands, and variations in geology, topography and grazing pressure can produce intricate (and sometimes baffling) gradations, mixtures and mosaics.

The heaths we have considered so far fall into a neat series of extensive heathlands on leached but stable soils across southern England. There are some lowland heaths that do not fit in with this pattern, notably the Breckland heaths of East Anglia (Fig. 217). These are on acid, sandy soils, derived from wind-borne ‘coversands’ deposited under dry periglacial conditions. The climate of the Breckland is dry and prone to late spring frosts. There are old records for bell heather and dwarf gorse in Breckland, but both are probably at the edge of their climatic tolerance there and no longer figure in the heathland flora. The surviving Breckland heaths are dominated by common heather, with bracken as the only other major player, but sheep’s fescue (Festuca ovina) is usually present, along with the moss Hypnum cupressiforme (sensu lato) and lichens such as Cladonia uncialis, C. portentosa, C. fimbriata, C. furcata, C. pyxidata, C. squamosa, Cetraria aculeata and Hypogymnia physodesH1. Sites such as Cavenham Heath and Lakenheath Warren have become classic ground for British plant ecology through the researches of Farrow and Watt. Coversands were also deposited in Lincolnshire and Nottinghamshire, where until relatively recently there were quite extensive heaths, and in the Vale of York where they are now mostly farmland, and only fragments of heathland (such as Skipwith, Strensall and Allerthorpe Commons) remain. An intriguing outlier of very ‘southern’ heath with dwarf gorse existed until the 1960s just west of Carlisle.

The Lizard district of Cornwall includes one of the largest outcrops of serpentine in Britain, and certainly the best known. Serpentine is an ultrabasic rock, rich in magnesium and heavy metals such as nickel and chromium, but poor in potassium and calcium. It is often attractively marbled and veined. Local craftsmen at the Lizard make trinkets and souvenirs out of it, and the harder forms have been valued for decorative carving and facings in building (‘Connemara marble’ is another serpentine rock, not a true marble). Many plants fail to thrive on serpentine soils, either because of heavy-metal toxicity, or because the ratio of calcium and potassium to magnesium is too low. But ‘one man’s meat is another’s poison’, and the Lizard is home to a remarkable concentration of plants rare in Britain, and some distinctive plant communities.

Lizard Head itself, the most southerly point in England, is on schist and has quite different vegetation from the serpentine just to the north. Any visitor driving to Kynance Cove in late summer cannot fail to notice the Cornish heath (Erica vagans, Fig. 225c) in flower, sometimes pink, sometimes white, in the ‘mixed heath’ on the roadside. Cornish heath is a southern species, occurring very locally in dry coastal heath in Brittany, and in the Basque country in France and Spain (it has one possibly native locality in Fermanagh and is naturalised on the Magilligan dunes). This Erica vagans–Ulex europaeus heathH6 at the Lizard is a species-rich heathland on deep mildly acid soil, which covers large areas of the cliff-top and well-drained valley sides for a few hundred metres back from the coast (Fig. 218). Cornish heath, bell heather, common and western gorse share dominance. Glaucous sedge (Carex flacca), common dog-violet (Viola riviniana) and dropwort (Filipendula vulgaris) are also near-constant. Many other species are frequent in the community, including tormentil, common heather, betony (Stachys officinalis), common milkwort (Polygala vulgaris), wild thyme (Thymus polytrichus), spring squill (Scilla verna), cat’s-ear (Hypochaeris radicata), bird’s-foot trefoil (Lotus corniculatus), lady’s bedstraw (Galium verum) and the grasses Dactylis glomerata and Danthonia decumbens. This heath is one of the glories of the Lizard.

FIG 228. The Lizard; Erica vagans–Ulex europaeus ‘mixed heath’ above Kynance Cove, (a) at the peak flowering season of Cornish heath (Erica vagans) in August 1970 and (b) the same vegetation in early May 1994, with common gorse in flower.

On the flat poorly drained plateau over serpentine between the main Helston–Lizard road and Coverack, another distinctive community covers wide tracts of ground. This Erica vagans–Schoenus nigricans ‘tall heath’H5 (Fig. 219) stands at a meeting-point of heath, fen and fen meadow. Cornish heath, black bog-rush (Schoenus nigricans), cross-leaved heath, Molinia and sometimes western gorse share dominance. Other characteristic plants include devil’s-bit scabious (Succisa pratensis), saw-wort (Serratula tinctoria), petty whin (Genista anglica), great burnet (Sanguisorba officinalis), glaucous sedge (Carex flacca), flea sedge (C. pulicaris), carnation sedge (C. panicea), bog pimpernel (Anagallis tenella) and the rich-fen mosses Campylium stellatum and Scorpidium scorpioides. Now that burning is much less frequent than 50 years ago, the smaller plants are less conspicuous than they were, and the species diversity of the heath appears to have declined.

FIG 229. The Lizard: Erica vagans–Schoenus nigricans ‘tall heath’ on Goonhilly Downs, September 1982. Two ‘dishes’ of the BT Goonhilly Earth Station appear on the skyline.

All of the dry heaths described above grade downwards with increasing wetness into a distinctive but rather uniform wet heath. Bell heather cannot grow below the level at which the soil is saturated during the winter because its roots are sensitive to the high concentrations of reduced (ferrous) iron in waterlogged soils, and the same is probably true of bristle bent. Wet heath is a widely distributed community, known as the ‘Ericetum tetralicis’ on the ContinentM16. Its dominant species with us are cross-leaved heath, common heather, Molinia and (if the heath has been burnt in the last decade or two) Sphagnum compactum (Fig. 230a). Other frequent species include Sphagnum tenellum (Fig. 230b), deergrass (Trichophorum cespitosum, for which this is the main habitat in southeast England), bog asphodel (Fig. 230f), round-leaved sundew (Drosera rotundifolia), common cottongrass (Eriophorum angustifolium), Campylopus brevipilus (perhaps currently being ousted by the introduced C. introflexus) and the lichens Cladonia portentosa (Fig. 235e) and C. uncialis. Runnels through the wet-heath belt provide a habitat for oblong-leaved sundew (Fig. 230d), white beak-sedge (Fig. 230c) and, much more locally, brown beak-sedge (Rhynchospora fusca) and marsh clubmoss (Fig. 230e), especially a few years after a heath fire. The floristic affinities of wet heath are with bog rather than with dry heath. With still wetter conditions the wet heath grades into valley-bogM21 and this in turn into tussocky MoliniaM25. The Ericetum tetralicis wet heath can intergrade in various directions – laterally into tussocky Molinia, with slight base-enrichment into a version dotted with heath spotted-orchids (Dactylorhiza maculata, Fig. 231a) and lousewort (Pedicularis sylvatica), and through that into the heathy form of Cirsio-Molinietum fen meadow (M24).

Many of our heathlands are probably very old, dating back to Bronze Age or Neolithic forest clearance or maybe in some places even further back than that. How far they were ever used to grow crops is uncertain, but certainly the main traditional use of heathland was low-density grazing of stock – sheep, ponies and cattle – much as on our uplands now. This has probably been so since prehistoric times. Heath fires were a common occurrence. Some of these were accidental, but burning was used deliberately to encourage new growth, and to get rid of old ‘leggy’ heather and gorse, and the mattress of dead leaves left by Molinia at the end of the season. The frequency of burning, and the balance between burning and grazing, has probably varied widely, but either would prevent colonisation of the inhospitable heath soils by trees. Arguably, Calluna and the other heathers are as fire-adapted as Banksia and the mallee Eucalyptus species in Australia. The west-European heaths could be seen as a fire-adapted ecosystem replacing oak forest, just as the fire-prone scrublands of the Mediterranean replace climax evergreen oak (Quercus ilex) forest.

FIG 230. Wet-heath plants: (a) Sphagnum compactum; (b) S. tenellum; (c) White beak-sedge (Rhynchospora alba); (d) Oblong-leaved sundew (Drosera intermedia); (e) Lycopodiella inundata; (f) Bog asphodel (Narthecium ossifragum).

FIG 231. A common and a rare wet-heath plant: (a) heath spotted orchid (Dactylorhiza maculata); (b) marsh gentian (Gentiana pneumonanthe).

With neither grazing nor burning, our heaths are invaded by trees, and something must replace traditional management if they are to continue as open heathland. Scots pine, introduced for landscape planting and for forestry, finds a congenial home in heathland, and many heaths in Surrey and the New Forest have been taken over by it. On slightly better soils birch (Betula pendula and B. pubescens) is the main colonist. Both pine and birch have light wind-borne seeds.

Many heathland plants are at their best 5–10 years after a heath fire. These include marsh clubmoss, the sundews, white and brown beak-sedge, the very local and beautiful marsh gentian (Fig. 231b) and many of the mosses and lichens. A heath long-unburnt tends to be a very dull place, and heathland managers who will not use burning for management bear a heavy burden of guilt for declining biodiversity in our heathlands. This is as true of the heathland animals as it is of the plants. A heath fire is tough on those individual plants or animals that happen to be above ground at the time – but occasional fire is what has created their habitat. Burning must not be too frequent; about every 15 years seems to be about optimal for our heaths. Mowing is no substitute, and grazing alone does not have the same effect.

In upland areas and on rugged coasts from southwest England, Wales, Cumbria and Galloway to Kerry and Connemara a heather moor dominated by common heather, bell heather and western gorse is widespread on well-drained acid soilsH8 (Fig. 212). The dominant plants leave little room for other species, but tormentil, common dog-violet, heath bedstraw (Galium saxatile), fine-leaved fescues (Festuca ovina, F. rubra), sweet vernal-grass (Anthoxanthum odoratum), common bent (Agrostis capillaris) and heath-grass (Danthonia decumbens) are frequent. St Dabeoc’s heath (Daboecia cantabrica, Fig. 225e) is locally common in this community in Connemara, probably avoiding the peatier and most nutrient-poor sites.

FIG 232. Calluna–Ulex gallii heathH8, widespread on exposed rocky ground at the coast, as here near Land’s End, September 1982, and up to moderate altitudes on our western hills.

On Mendip and the south Wales coast, where this community occurs on thin acid soils over limestone, transitions to limestone grassland occur, analogous to the ‘chalk heaths’ of the Downs, with calcicoles including salad burnet (Sanguisorba minor) and common rock-rose (Helianthemum nummularium), and species such as glaucous sedge, devil’s-bit scabious, slender St John’s-wort (Hypericum pulchrum) and betony (Etherington 1981). Western gorse does not occur in the Burren, so although there are plenty of limestone heaths on Black Head and the tops towards Ballyvaghan, none are analogous to this community.

From the English Midlands north to much of the Pennines and the North York Moors heaths and heather moors tend to be almost pure Calluna, enlivened only by a thin understorey of wavy hair-grass and mosses, mainly Pohlia nutans and Hypnum jutlandicum (Fig. 235d)H9. This rather dull moorland, grazed by sheep and in places managed for grouse, is a monument to the air pollution from the heavy industry that underpinned Britain’s economic prosperity a century ago. It is not wholly without variety; bilberry is locally quite prominent, especially on the sharply drained scarps and crags of Millstone Grit, the ‘bilberry edges’, of the south Pennines. These moors are in effect an impoverished version of the next community, and show signs of recovery towards it, but it is a slow process.

The really widespread kind of upland heather moor from Cornwall to Shetland and on the eastern uplands of Ireland is dominated by heather with variable amounts of bilberry, with scattered wavy hair-grass and a suite of bryophytes including Dicranum scoparium, Hypnum jutlandicum, Pleurozium schreberi (Fig. 235a), Hylocomium splendens (Fig. 89d) and Ptilidium ciliare, and lichens such as Cladonia portentosa (Fig. 235e), C. uncialis, C. pyxidata and C. cocciferaH12. Bell heather and crowberry (Empetrum nigrum) are frequent, as is tormentil. There is some regional variation. This community intergrades with the Calluna–Deschampsia flexuosa heath in the Welsh border counties and the north of England. Cowberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea), rare in the south, takes an increasingly prominent role in heather moor northwards, especially in the eastern Highlands.

In the north of England and Scotland heather moorland is widely used as grouse moor. Mostly these are maintained by controlled burning in small patches, which creates a patchwork of different ages. The younger growth provides a nutritious food supply, while the taller older patches provide good cover for the nesting birds within a short distance. This rotational burning produces a characteristic (but hardly pretty) pattern in the grouse moors (Fig. 213). It perpetuates open heather moor, and benefits nature conservation, provided the rotation is not too short, and especially if steep rocky areas of heather are left unburnt. Nature conservation on many lowland heaths would benefit from similar rotational burning, but probably in larger patches and on a somewhat longer rotation.

FIG 233. Muirburn pattern in heather–bilberry moorlandH12, eastern foothills of the Cairngorms near Tomintoul, September 1980.

On thin, acid, sharply drained soils around rock outcrops and similar dry heathy places the heather–bilberry moor gives way to a distinctive community dominated by the two heathers Calluna and Erica cinerea, with tormentil as the only other near-constant speciesH10. Heath bedstraw, sheep’s fescue, sweet vernal-grass, wavy hair-grass, common bent, green-ribbed sedge (Carex binervis), hard fern (Blechnum spicant) and the mosses Dicranum scoparium, Racomitrium lanuginosum, Pleurozium schreberi, Hypnum jutlandicum, Hylocomium splendens and lichens such as Cladonia portentosa and C. uncialis are frequent to occasional. The influence of the wet oceanic climate is shown by occasional cross-leaved heath and deergrass. This community has a similar overall geographical distribution to the last. It is common on steep rocky ground near the west coast, but it occurs inland too, and it is well represented in the eastern Highlands.

FIG 234. Deergrass moorlandM15, showing typical autumn colour, east of Beinn Bhan, Applecross, Wester Ross, September 1974.

Wide tracts of country on peaty soils in the west of Wales, Ireland and above all Scotland are dominated by a wet heath or degraded blanket-bog community, firm underfoot, dominated by deergrass, cross-leaved heath, Calluna and MoliniaM15. This community covers thousands of monotonous hectares in the western Highlands and islands (Fig. 214), and probably covers proportionately as much of the landscape in west Wales and in the blanket-bog districts of Ireland. Apart from the dominants the most frequent species are common cottongrass, bog asphodel, round-leaved sundew and bog-myrtle (Myrica gale). A long list of other bog, poor-fen and acid-grassland species occur occasionally, including several species of Sphagnum. The geographical limits of this community are almost the same as the heather–bilberry moor, but it covers wider expanses of ground in the west.

The heath shrubs have their growing-points at the tips of their branches. Grasses keep their growing-points at ground level, protected by the bases of the leaves. Because of this, heathers are much more severely set back by fire or grazing. In the year following burning, fire-lines can be very striking by the colour-contrast between the luxuriant growth of the grass and the unburnt heath. This may be seen by a farmer as a desirable outcome, and under favourable conditions, if grazing animals are put onto recently burnt ground, the heath can be transformed into grassland in only a few years. Most of our acid hill grasslands must have originated in essentially this way, by some combination of felling, grazing or burning on pre-existing forest or heath.

On dry, nutrient-poor soils developed over hard, acid rocks (granite, rhyolite, hard sandstones and grits) or impoverished sands, the thin turf is dominated by sheep’s fescue (Festuca ovina) and common bent (Agrostis capillaris), with sheep’s sorrel (Rumex acetosella) as the commonest associate. Some other small plants are frequent or occasional, including early hair-grass (Aira praecox), whitlowgrass (Erophila verna), stork’s bill (Erodium cicutarium) and shepherd’s cress (Teesdalia nudicaulis). Many other species occur occasionally. Mosses and lichens are sometimes conspicuous, the most frequent being Dicranum scoparium and Brachythecium albicans. This Festuca–Agrostis–Rumex acetosella grasslandU1 has a wide but scattered distribution from the south coast of England to central Scotland. Much of what was lowland ‘grass-heath’ in Tansley’s day is now farmland.

Much more widespread is the Festuca ovina–Agrostis capillaris–Galium saxatile grasslandU4. This is arguably our most important hill-pasture type. It occupies mildly acid brown-earth soils over rocks that are neither excessively base-poor nor calcareous. It is almost ubiquitous throughout our uplands from Devon and Cornwall to Shetland and the Western Isles, and similar vegetation occurs in Ireland. The turf is dominated by sheep’s fescue and common bent, with abundant sweet vernal-grass; tormentil and heath bedstraw (Galium saxatile) are nearly always present. Other frequent species include field wood-rush (Luzula campestris), common dog-violet, Yorkshire-fog (Holcus lanatus), yarrow (Achillea millefolium), white clover (Trifolium repens), common mouse-ear (Cerastium fontanum), self-heal (Prunella vulgaris), lady’s bedstraw, mountain pansy (Viola lutea) and bird’s-foot trefoil, and mosses including Rhytidiadelphus squarrosus (Fig. 235b), Pseudoscleropodium purum, Dicranum scoparium and Hypnum cupressiforme (sensu lato). Typically this community occupies the uppermost enclosed fields on a hill farm, and the relatively steep lower slopes of the unenclosed land (Fig. 238). It provides good grazing. The enclosed fields may be ploughed and re-sown, but they revert towards the semi-natural Festuca–Agrostis pasture over the course of time.

FIG 235. Common mosses and lichens of heath, moorland and acidic grasslands. (a) Pleurozium schreberi; (b) Rhytidiadelphus squarrosus; (c) Polytrichastrum formosum; (d) Hypnum jutlandicum; (e) Cladonia portentosa; (f) Cladonia coccifera (agg.). These are two of the commonest species of Cladonia; there are many others.

The Festuca–Agrostis grassland is variable, depending on soil fertility and pH. In upland situations where the soil parent-material provides a modicum of calcium (as on various base-rich rocks in Wales or calcareous schists in Perthshire), the grassland is richer in species. In addition to those plants already noted, wild thyme (Thymus polytrichus) and harebell (Campanula rotundifolia) are near-constant in this Festuca–Agrostis–Thymus grasslandCG10, white clover, bird’s-foot trefoil and meadow buttercup (Ranunculus acris) are more frequent, and many other species occur occasionally, including quaking-grass (Briza media) and fairy flax (Linum catharticum).

Bracken (Pteridium aquilinum) hardly deserves a named community of its ownU20, because it is usually either a part of a woodland understorey or an invader into Festuca–Agrostis grassland (Fig. 216), which, at least initially, continues as an understorey beneath the bracken canopy. As a fern, bracken reproduces by spores, but these need damp sheltered conditions to germinate and for the prothalli to mature, fertilise, and produce sporeling ferns. Once established, bracken can spread far and wide by means of its long-creeping underground rhizomes. In a recently invaded pasture this radial spread of bracken is often very obvious; Fig. 48), and it is easy to see the point where it became established, often a wall or a patch of disturbed ground. Bracken is intolerant of waterlogging, and needs a fairly deep soil for growth of the rhizomes. Bracken had some agricultural value in the past, when it was often cut for bedding livestock, but now it is generally seen as an unwelcome invader of pasture, added to which, it is poisonous to livestock. Bracken is hard to control because a large part of the plant’s resources are underground in the rhizomes. Traditional methods of control, repeated cutting or crushing, were time-consuming and labour-intensive, and needed to be repeated year by year if they were to have an effect. Some success has been achieved in recent decades by aerial spraying with asulam, a systemic herbicide, which inhibits the development of frond initials and rhizome apices. Correctly timed and targeted application of a sufficient dose can certainly check bracken, but total eradication remains difficult.

FIG 236. The Llanthony valley in the Black Mountains, looking towards Darren Lwyd, August 1989. The enclosed fields on the gentle slopes are improved grassland. Bracken has spread to cover most of the potential bent–fescue grassland on the steeper slopes. There is some heather, mostly on the steeper slopes, and some mat-grass (Nardus stricta) on the flatter tops.

Some acid grasslands are in effect grazed facies of the corresponding heath. Deschampsia flexuosa grasslandU2 might be derived from any one of a number of heaths in which wavy hair-grass plays a part. It has a wide but scattered distribution in England, Wales and eastern Scotland, and is probably derived from different starting points in different places.

Agrostis curtisii grasslandU3 is clearly derived from Ulex gallii–Agrostis curtisii heath by burning and grazing, and most of the species of the heath are still to be found in the grassland. Nevertheless, the visual difference between the grassland and the heath is very great. Much of the pale fine-leaved grass seen in late summer on Dartmoor or Bodmin Moor is bristle bent rather than the pure expanses of mat-grass (Nardus stricta) that would be expected on upland areas farther north.

The mat-grass-dominated Nardus stricta–Galium saxatile grassland (replacing damp heather moor) covers wide tracts of upland country on moist, acid peaty-gley soils. Nardus starts into growth and flowers early in the spring, but quickly becomes tough, wiry and unpalatable to stock. It is of much less value for grazing than the Festuca–Agrostis pastures of the steeper and better-drained slopes. Nardus generally makes up the bulk of the herbage, but heath bedstraw, tormentil, sheep’s fescue, common bent and the moss Rhytidiadelphus squarrosus are usually present. The Nardus grassland often includes a seasoning of species from neighbouring vegetation – velvet bent (Agrostis canina), common sedge (Carex nigra) and the moss Polytrichum commune from acid poor-fen patches, sweet vernal-grass, heath rush (Juncus squarrosus), deergrass and bilberry from other heaths and grasslands, and the ubiquitous upland calcifuge mosses Dicranum scoparium, Hypnum jutlandicum, Pleurozium schreberi and Hylocomium splendens. Nardus grassland is far from being as species-poor as its apparent uniformity might suggest.

Molinia is often prominent in the uplands, on valley floors, and on gentle slopes with damp peaty soilsM25. The leaves die at the end of the growing season, leaving copious leaf-litter but providing no winter grazing (Fig. 217). Like Nardus, it starts into growth relatively early, but by the time the ewes and lambs are on the hills there is more palatable pasture available.

Heath rush is the remaining player in the hill-grassland scene. It could be said that the Juncus squarrosus–Festuca ovina grassland’U6 is a grassland only in name. It grows on damp peaty soils on gentle slopes or flattish tops, often forming an irregular zone above the Nardus grassland. It is dominated by varying proportions of heath rush, sheep’s fescue and the moss Polytrichum commune. The balance of the community is made up of a mixture of poor-fen, wet heath and bog species – common sedge, velvet bent, cottongrasses, Sphagnum papillosum and a string of other bryophytes including the mosses Dicranum scoparium, Hypnum jutlandicum, Pleurozium schreberi, Rhytidiadelphus squarrosus, R. loreus, Hylocomium splendens and the leafy liverworts Lophocolea bidentata, Lophozia ventricosa, Barbilophozia floerkei and Ptilidium ciliare. The Juncus squarrosus rush-heath is a product of burning and grazing other vegetation, perhaps most often a late stage in the degradation of upland blanket bog.

FIG 237. Burning damp Molinia pasture (here with clumps of rushes, Juncus effusus), near Simonsbath, Exmoor, 4 April 1980. ‘Swaling’ was traditional practice among upland farmers to encourage fresh green growth.

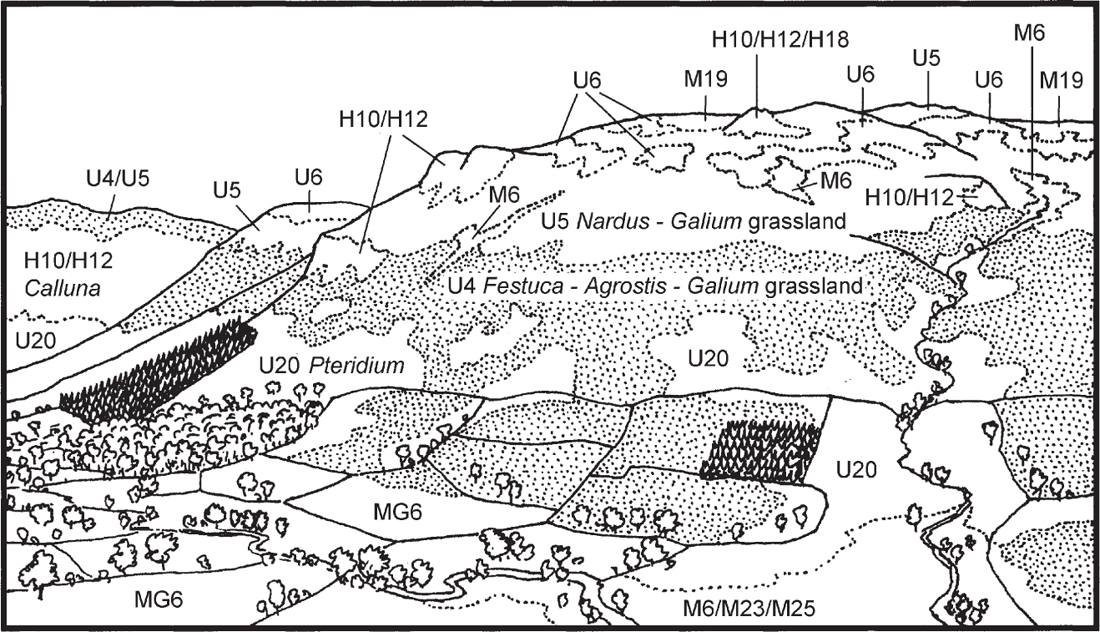

The heather moors and upland acid grasslands are the main ingredients of the hill-farming landscape (Fig. 238). In autumn, the various dominants with their distinctive colours make up a multi-hued patchwork covering the landscape. The improved fields in the valleyMG6 will still be bright green: if a hay crop has been taken off the grass will have had time for a fresh flush of growth. The Festuca– Agrostis pasturesU4 on the valley sides will be a more subdued shade of green and the bracken will already have turned red-brown. Patches of Calluna–Erica cinereaH10 and Calluna–Vaccinium heathH12 will be dark brownish green (with a light pinkish-brown tinge if there is a lot of Vaccinium). Nardus grasslandU5 on the gentle higher slopes will be a pale straw colour; MoliniaM25 will be slightly less pale and a warmer hue. Juncus squarrosus will be dark brownishU6, and blanket bogM19 on the summits will be dark brownish-green from the heather, perhaps with a reddish tinge from the autumn colour of the cottongrass leaves.

FIG 238. Schematic hill-farming landscape showing the distribution of some common upland vegetation types. MG6 is the rye-grass–crested dog’s-tail improved grassland of the fields in the valley. Stippling marks the Festuca ovina–Agrostis capillaris–Galium saxatile pasture (U4) of the lower slopes, sometimes colonised by bracken (U20). Above this is a zone of mat-grass (Nardus stricta) grassland (U5) on peatier soil, with patches of heath rush (Juncus squarrosus) (U6). The summit is capped by upland blanket bog (M19). Sharply drained rocky terrain bears Calluna–Erica cinerea heath (H10) or Calluna–Vaccinium myrtillus heath (H12). Wet uncultivated ground in the valley is a mix of acid mire, rushy pasture and Molinia. Adapted from Averis et al. (2004).

But this is farming country, and the pattern of the landscape has grown from the hard economic realities of making a living from it. The various moorland and hill-grassland types are of different value for grazing livestock. In sheepwalks in mid Wales studied in 1938, the grazing density was greatest on Agrostis-dominated swards at any time of year. In June, the grazing on any other type of sward was less than a fifth of the grazing on Agrostis, but over the year as a whole the figure was 30–40% for all but the wettest swards. In Snowdonia in June 1945, Agrostis–Festuca grasslands supported the highest densities of sheep, fescue–heather or fescue–bracken mixtures rather less, and other sward types with Nardus or Molinia less again. Over the year the Agrostis–Festuca swards supported on average 2.8 ewes per acre, Nardus and Molinia swards less than 1.4 (Hughes 1958). In the Cheviot region of southern Scotland, the year-round order of grazing intensity was bent–fescue 151, open bracken (with bent–fescue) 137, Nardus 72, soft-rush infested pasture 69, Molinia 55 (Hunter 1962). Bent– fescue (with or without an open cover of bracken) was almost equally favoured in any month of the year. Nardus, heather and heather–hare’s-tail cottongrass (Eriophorum vaginatum) on deep peat were most favoured in winter, and the rush-infested pasture in February and from May to July (perhaps for shelter – ‘a clump of rushes is worth a shilling’). These figures are from mid-twentieth-century sheep farming, which has changed, just as farming has changed in the past. In former centuries cattle outnumbered sheep in upland Snowdonia, and were nearly as numerous as sheep and goats combined. The cattle needed herding to take advantage of the short growing season on the high hills and were brought down to the valley in winter. Transhumance from the lowland hendre to the upland hafod (sheiling, buaile or booley) was the norm. Sheep only became predominant with the enclosures from the eighteenth century onwards. Until a century ago, mutton was in demand and the wethers overwintered on the open hill pastures, where they grazed what they could from Nardus and Molinia, and were on the ground when these grasses started into growth (Roberts 1959). Our problems with the conservation on lowland heaths in England come about because the agricultural practices that created and maintained them are no longer economically relevant and have fallen into disuse. Grouse moors and hill grasslands are part of a living cultural landscape. For that, we should cherish them more, not less.