Holy Roman Empire at the end of the Thirty Years’ War in 1648.

. . . the attention will be excited by an history of the decline and fall of the Roman empire; the greatest perhaps, and most awful scene in the history of mankind.

—Edward Gibbon, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1788)

America has been the latest great power whose intents, accomplishments, and failings have been compared to the actions of the Roman Empire and whose future has been foreseen as a variant of Rome’s decline and fall, the description of the demise of a powerful state that Edward Gibbon’s lifework inseparably attached to the most extensive and longest lasting of all Mediterranean empires1.Inevitable comparisons with its achievements began just a few centuries after the transformation of the Western Empire into a group of smaller Christian kingdoms with Charlemagne’s (742-814) effort to consolidate some of these states into a new political entity that was considered to be a continuation of its august predecessor.

Four other states, or at least some of their rulers or political or ecclesiastical elites, have attempted to pattern explicitly some of their actions on Roman precedents, or have claimed to be in some important ways the inheritors or perpetuators of Rome’s grand mission. After the demise of the Byzantine Empire some wanted to see Czarist Russia as the Third Rome; Napoleonic France chose explicitly Roman symbols and procedures in the aftermath of revolution and terror; the British Empire based its claim above all on the extent of territories under its rule of law; and Mussolini created a short-lived caricature of an imperial order that was, after a lapse of nearly 1,500 years, once again based in Rome.

Charlemagne’s empire was deliberately fashioned to be seen as Rome’s direct descendant. Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne in St. Peter’s Basilica on Christmas Day of 800 as Imperator Augustus, bestowing on him the same name the Roman senate granted in the same city to Octavianus, the first princeps, in 27 B.C.E. But it is the year 962 (coronation of Otto I) that is usually taken as the formal beginning of Sacrum Romanum Imperium, the Holy Roman Empire (Bryce 1886; Heer 1968). Its language was Latin, its laws rested on Roman foundations, until after 1500 its emperors were crowned in Rome, they did not shun expansionary warfare, and the empire was long-lived: its official dissolution took place nearly 850 years after its establishment, in 1806, when the Habsburg Emperor Francis II renounced the title. But profound differences between the two empires have always made for only a superficially valid and ultimately unconvincing set of parallels.

The dates for the duration of the Holy Roman Empire bracket the history of something that was more an aspiration, a lofty concept, than a well-integrated political, strategic, or economic entity. The empire was far too splintered (it eventually consisted of more than 300, mostly small, principalities), and its always complicated internal politics and testy relations with Rome were far too unruly for that: “Neither holy, nor Roman, nor an empire,” was Voltaire’s famous verdict. 2 And even at the time of its greatest extent its territory embraced only a fraction of the original Western Roman Empire, cutting a wide swath across the central part of Europe from the Baltic to the Tyrrhenian Sea (figure I.1).

Its power came overwhelmingly from the multitude of its German jurisdictions, hence its common name Heiliges Römisches Reich deutscher Nation (Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation). But this was an inaccurate description because the empire also included entire territories of the ancient kingdom of Bohemia and Moravia (those were never part of the Roman Empire),3 Austria, Switzerland, today’s Belgium and the Netherlands, and parts of northern and central Italy. As a result, the empire had also governed Czechs, Slovenes, French, Dutch, Italians, and Jews. France (except for a strip along German, Swiss, and Italian borders), the Iberian Peninsula, and England were entirely beyond the empire’s reach, as were any territories in Eastern Europe.

The notion of Russia as the Third Rome (tretii Rim) was considered to be a part of the Russian national idea, and some saw it as a major impetus for Russia’s imperial expansion. The reality was different. Expansion from the medieval central Russian core (all the way to the Pacific Ocean by the mid-seventeenth century, followed by the penetration of Central Asia to the borders of Iran and Afghanistan during the nineteenth century) was not driven by such considerations. Russia as the Third Rome was primarily an ecclesiastical idea that was born after the conquest of Constantinople and the demise of the Eastern Roman Empire in 1453. It was based on the fact that Russia then became the largest Orthodox state (and a spiritual successor of the fallen Byzantine Empire), and it was given additional support by the marriage of Czar Ivan III to Sophia Palaiologos, a niece of the last (Eastern) Roman Emperor.

The idea of tretii Rim was formulated in some detail at the beginning of the sixteenth century by Filofei, a monk in Pskov. As Rowland (1996) noted, it has been irresistibly appealing to historians (some of them compiled extensive references to its use), but its original mission was not to justify expanding the empire but to strengthen the position of the Russian patriarchate with the Eastern Orthodox Church and to limit rather than increase the country’s secular powers. As such, the concept did not have notable imperial influence, and it was later much criticized in Russia itself, but at the same time it has always retained some of its vague mythical appeal. That is how we should understand the references to the Third Rome that continue to appear in modern Russian publications (Panarin 1996; Luks 2002).

The French Revolution followed the sequence from Roman republic to new empire as its guiding political example, right down to the first consul’s being elevated to emperor by the senates-consulte. Huet (1999) described all the deliberate parallels between the rise to power of Augustus and of Napoleon Bonaparte (consul for life in 1802, emperor in 1804) and the myth of Napoleon as a Roman emperor, a delusion that cost Europe several million lives (Ribbe 2005). Compared to Napoleon’s brief rule of excess, the British Empire of the nineteenth century had a much better claim for a meaningful comparison with the Roman achievements.

In 1831 the first edition of Encyclopedia Americana noted that “imagination sinks under the idea of this prodigious power in the hands of a single nation [Rome] . . . But another paramount dominion was yet to be created of a totally different nature; less compact, yet not less permanent, less directly wearing the shape of authority, yet, perhaps, still more irresistible; and in extent, throwing the power of Rome out of all comparison—the British empire. Its scepter is influence.” And that was decades before Britain acquired and consolidated its vast (Cape-to-Cairo) African possessions.

The comparison came naturally to many of those who ran the British Empire, a small group of classically educated officials and top military men who enlarged it and administered it for generations (Gilmour 2007).4 Gilbert Murray (1866-1957) made the imperial comparison explicitly (if inaccurately): “At home England is Greek. In the Empire she is Roman.”5 Alfred Lyall (1835-1911), after long service in India (he ended his career in 1887 as the lieutenant-governor of North West Provinces and chief commissioner of Oudh) believed that future historians would see the British Empire “as a second remarkable illustration of the force with which a powerful and highly organized civilization can mould the character and shape the destinies of many millions of people” (1906, 348). Those who think this statement hubristic should consider the profound cultural impact the empire had on its most prized possession, India (Mustafa 1971; Wild 2001).

In an essay published in 1908, Evelyn Baring (Lord Cromer, 1841-1917, who was consul general in Egypt for nearly 25 years) approved of Lyall’s search “in the history of Imperial Rome, for any facts or commentaries gleaned from ancient times which might be of service to the modern empire of which he was so justly proud,” and he believed that “the intentions of the British, as compared with the Roman Government are, however, noteworthy from one point of view, inasmuch as from a correct appreciation of those intentions it is possible to evolve a principle perhaps in some degree calculated to avert the consequences which befell Rome, partly by reason of fiscal errors (1908, 21).”

In 1912, Charles Lucas (1853-1931) completed Greater Rome and Greater Britain, and two years later a jurist and historian, James W. Bryce, (1838-1922) published a long essay comparing the Roman Empire and the British Empire in India. Its first paragraph affirmed the exceptionalism of the two phenomena (1914, 1):

There is nothing in history more remarkable than the way in which two small nations created and learnt how to administer two vast dominions: the Romans their world-empire, into which all the streams of the political and social life of antiquity flowed and were blent; and the English their Indian Empire, to which are now committed the fortunes of more than three hundred millions of men. A comparison of these two great dominions in their points of resemblance and difference, points in which the phenomena of each serve to explain and illustrate the parallel phenomena of the other, is a subject which has engaged the attention of many philosophic minds, and is still far from being exhausted.

He could not know that in just two generations the British Empire would have shrunk to less than a score of small insular outposts. There is, of course, no universally accepted starting date of the British Empire. Its beginning may be seen in bold trans-Atlantic forays of Elizabethan explorers (Francis Drake, Martin Frobisher, Henry Hudson, Walter Raleigh) during the closing decades of the sixteenth century; in the founding of the East India Company (it obtained its Royal Charter in 1600); or in the nearly concurrent setting up of the first American colonies (Jamestown in 1607, Plymouth in 1620). Following Cain and Hopkins (2001) and taking the revolutionary year of 1688 as the origin of British imperialism, there are almost exactly two centuries to the empire’s apogee in the year 1897, when Britain celebrated its monarch’s Diamond Jubilee and when invocations of the analogies between the two empires became commonplace. At that time the two key simple quantitative comparisons clearly favored the new empire.

At the peak of its power Rome controlled a territory of no more than about 4.5-5 million km2 (with modern Turkey, modern France, the Iberian peninsula, and Italy as its largest components). 6 In contrast, after the end of World War I (WW I) the British Empire covered about 30 million km2 (figure I.2). Even when that total is reduced by subtracting uninhabited or very sparsely populated deserts of Britain’s African possessions (Egypt, Sudan, and South Africa), the arid interior of Australia, and the sub-Arctic and Arctic near-emptiness of Canada, the remainder of at least 15 million km2 was roughly three times as large as the lands under the Roman Empire.

In terms of population totals, the best estimates for the Roman Empire at the beginning of the fourth century C.E.(under Constantine, the first Christian emperor) are fewer than 60 million people, with roughly a 40/60 split between the western and eastern parts (Russell 1958). In contrast, at the beginning of the twentieth century the British Empire had a total population of almost 400 million people. The famous eleventh edition of Encyclopaedia Britannica, published in 1911, offered an improbably precise total of 388,712,785 people, of which three-quarters lived in the Indian subcontinent; the 1901 census counted 294,191,379 people, compared to the United Kingdom’s total of less than 42 million (Lugard 1910).

But in the longevity comparison the British Empire came up short. If 1897 was its peak, the decline set in almost immediately afterward with the defeats during the Boer War in battles at Magersfontein (December 1899) and Spion Kop (January 1900). As the British troops were leaving the Southampton docks in October 1899 to fight that distant war, Thomas Hardy wrote of their embarkation with a distinctly martial Roman allusion (1901, 116):

Here, where Vespasian’s legions struck the sands,

. . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Vaster battalions press for further strands,

To argue in the self-same bloody mode

Which this late age of thought, and pact, and code,

The Boer rebellion was over by 1902, but soon came the mass slaughter and entrenched exhaustion of British troops during WW I (1914-1918), followed by India’s relentless unrest as Britain became engaged in the existential struggle of World War II (WW II). Concurrently, the Arab-Jewish conflict in Palestine worsened after 1938 and became intolerable after 1945, leaving Britain eager to relinquish its mandate. The formal beginning of the empire’s end came just 50 years after Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee, with the withdrawal from India (on August 15, 1947) and the subcontinent’s tragic partition (Khan 2007). If one takes 1688 as the empire’s beginning and 1947 as its de facto end, the British Empire spanned about 260 years, a quite respectable run as far as the longevity of empires is concerned but far short of the persistence of power of ancient Rome.

After leaving India it took Britain about two decades to divest itself of all sizable African possessions: Bechuanaland (Botswana) was the last major colony to get independence, in 1966. 7 And almost exactly 50 years after leaving India, on July 1, 1997, came the British retreat from Hong Kong, the empire’s most lucrative Asian outpost, held since the Opium War of 1842. That withdrawal has left Britain in the possession of only ten small inhabited island colonies whose total population in 2008 was about 180,000 people, the most populous being Bermuda (about 60,000), the least populous a tiny Pitcairn in the vastness of the South Pacific halfway between New Zealand and South America with some 50 people (mostly the descendants of Bounty mutineers who landed in 1790).

If Britain carried the imperial comparison as a consequence of its indisputable achievements and as a mark of its far-flung obligations, Benito Mussolini (1883- 1945) was delusionary enough to insist on a re-creation of the Roman Empire itself. Indeed, his quest went even deeper as Romanità (Romanness), a multifaceted heritage from the classical Roman past, had a central place in legitimizing fascist rule (Nelis 2007). On April 21, 1922 (Birthday of Rome, a holiday created by Mussolini), il duce presented an abstract version of Rome as the foundation of his fascist state: “Rome is our point of departure and reference; it is our symbol or, if you wish, our myth. . . . Much of what was the immortal spirit of Rome, resurges in Fascism. . . . Roman is our pride and courage: Civis Romanus sum” (cited in Nelis 2007, 403).

In 1925, three years after he took power, Mussolini envisaged a Rome that must appear not just marvelous to all the peoples of the world but also vast, ordered, and powerful as it was at the time of Augustus (Minor 1999). Augustus was Mussolini’s model (in 1937, to commemorate the two thousandth anniversary of the first emperor’s death, il duce restored his mausoleum on the Campus Martius) 8 and fascism meant for him above all the “will to empire.” Roman symbols—fasces, eagles, and short swords (gladia)—appeared on buildings and propagandistic posters, and architects began to design modern versions of such quintessential Roman structures as triumphal arches, heroic mosaics, and monumental marble statues.

A new forum (Foro Mussolini, now Foro Italico) included Stadio Mussolini built of traditional marble and brick and surrounded, like the ancient circuses, by white heroic male statues symbolizing virility and strength. The forum also had an obelisk inscribed Mussolini Dux (Mras 1961; Minor 1999). In April 1934, Mussolini unveiled four large marble maps on the wall of the Basilica of Maxentius along the newly created Via dell’Impero (now Via dei Fori Imperiali), which he ordered built between Piazza Venezia and the Colosseum so that his victorious armies could parade in view of great monuments, much like the Roman legions during their triumphal parades staged by the emperors after faraway conquests.

The maps are still there, marking the progression of the Roman Empire from a single white dot in the eighth century B.C.E. to the empire’s greatest extent under the emperor Trajan by 117 C.E. (figure I.3). In October 1935 the Italian army invaded Ethiopia in order to add a major colonial possession to the territories of Somalia and Eritrea, which Italy had controlled since 1889, and Libya, which it had occupied as a result of the war with Turkey in 1911. Addis Ababa fell just seven months later, on May 5, 1936, and Mussolini’s proclamation of the new empire on May 10, 1936, was obviously patterned on adlocutio cohortium (a speech given by an emperor to his legions). 9 He made the connection between the two empires explicit (cited in Minor 1999, 154): “raise high—legionaries—your standard, your weapons, and your hearts, and salute, after fifteen centuries, the reappearance of the Empire on the predestined hills of Rome.”

In October 1936 a fifth map was put up on the Via dell’Impero showing the white-marbled Italy, Libya, Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Somalia, a new impero del’Italia fascista; Albania was added after Italy occupied it in 1939 (figure I.4). And, in a truly pathetic display of me-too craving, in 1937, Mussolini, copying the habitual Roman thefts of Egyptian antiquities, ordered the looting of a massive obelisk from Axum in northern Ethiopia and its removal to Rome, where it was installed in front of a newly built Ministry for Colonies. 10 But Mussolini’s new impero lasted less than nine years, and the fifth map was broken up and removed from the wall.

Marble maps of the Roman Empire placed on the wall of the Basilica of Maxentius by Mussolini in 1934. Photo by V. Smil.

The United States, initially reluctant to enter yet another world war, emerged from the war against Germany and Japan as the world’s greatest economic power and as the only possessor of nuclear weapons. But the USSR, despite the enormous destruction it suffered during the war, became an aggressive competitor. The Cold War was on, and it brought forth vituperative parallels between the behavior of the ancient Roman Empire and the might and mores of the United States. The Stalinist propaganda of my grade school years (when I lived in the westernmost outpost of the Soviet empire) and its much less odious Khrushchevian-Brezhnevian version of the late 1950s and the 1960s saw the U.S. military bases surrounding the USSR and the “expansionist” wars in Korea (never mind that Stalin’s consent started that one), 11 Vietnam, and the Middle East (by proxy, via Israel) as signs of America’s grand imperial design to dominate the world and to “enslave progressive forces” fighting for social justice and self-determination.

Mussolini’s impero del’Italia fascista included Libya, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia, and Albania.

Communist propagandists saw a militaristic, expansionist, and enslaving Washington as an inheritor of evil Roman ways, and the European left (from French Stalinists to radical Scots Labourites) held similar views. In the United States itself this comparison and the search for analogies and similarities between the two societies, separated by two millennia of time, was hardly center stage until a mélange of events and trends made the notion almost commonplace; empire is currently part of a new political and cultural vocabulary used by liberals and conservatives alike. The shift began with a rapid unraveling of Soviet power during the late 1980s that culminated in the dissolution of the USSR in 1991, a remarkably peaceful process that was formally sealed on December 8, 1991. 12

Less than ten months before this epochal event America’s military dominance and unmatched strategic might were confirmed by a victory of the U.S.-led coalition over the Iraqi army in the first Gulf War, which lasted only six weeks (January 17-February 27, 1991). This was not just a swift and lopsided war but one that ended with the utter destruction of the enemy on the battlefield, an achievement symbolized by the mass of obliterated hardware as the U.S. Air Force demolished the retreating Iraqi Army along the infamous “Highway of Death” north of Kuwait City. The war’s offensive operations were actually cut short in order to prevent the continuation of this “turkey shoot.” 13

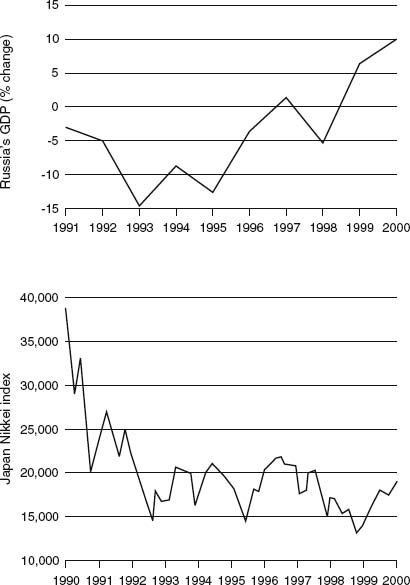

This victory, a triumphant demonstration of America’s superpower status, was potentiated by two remarkable economic retreats, those of the country’s foremost strategic enemy (USSR) and of its most worrisome economic competitor (Japan). The collapse of the Soviet command economy and the rise of mafia-like business structures in the post-Soviet society were marked by a substantial decline of Russia’s GDP: it fell by 5% in 1991, 14% in 1992, 9% in 1993, and 13% in 1994, and it did not bottom out until 1998, when its per capita rate was (in inflation-adjusted monies) just 60% of the 1991 level (figure I.5) and its average real income about half of the peak Soviet rate (Smil 2008b).

As for Japan, the Nikkei index (its leading stock market indicator) rose from a bit over 13,000 by the end of 1985 to nearly 39,000 in December 1989, and it was widely expected that the country would emerge as the world’s leading economy in the early twenty-first century. But it was a classic bubble economy, and it burst in spectacular fashion: by the end of 1990 the Nikkei index fell to less than 24,000, and by the end of the 1990s it was below 14,000 (see figure I.5). 14 There is no historic precedent for such a rapid move from globally admired economic superpower to floundering society enmeshed in a prolonged socioeconomic crisis. But America’s economic performance looked good not only in comparison with the much weakened post-Soviet states and with Japan’s deflating economy.

During the 1990s the perception of America’s unique imperial status was boosted by the country’s vigorous economic sprint, led by innovative high-tech companies whose efforts helped to turn microprocessors, computers, and the newly commercialized World Wide Web into products and services that formed the admirable New Economy of the 1990s. This was a surprising development because it followed the troublesome 1980s, when Japan’s economic power appeared to be unstoppably ascendant and America seemed destined to become a marginalized, has-been power in the new century (Smil 2008b). This included a widespread belief that America would lose its leadership in electronic innovation.

Aftermath of an empire and the retreat of a great economic power: Russia’s declining GDP and Japan’s falling stock market of the 1990s. Plotted from data available at Russia’s Federal Service of Government Statistics and Nikkei Net Interactive.

But during the 1990s U.S. GDP grew by an average of 3% per year, a satisfyingly high rate for such a large economy. Moreover, the U.S. share of global economic product (expressed in market exchange terms) rose from nearly 26% in 1990 to about 31% by 2000. And added to America’s newly enhanced military and economic might was the influence of its soft power, the worldwide appeal of its ideas, inventions, products, and way of life. 15 Some of these soft power influences have clearly been detrimental (for instance, the diffusion of fast food served in gargantuan portions), others naive (a computer for every child is no guarantor of true literacy). No matter—they were all addictive, diffused rapidly, and once abroad appeared irrepressible. 16

While America thus advanced abroad, at home its wealth created excessive consumption that spread far beyond the traditional high spenders. Steadily falling savings rates and readily available credit made it possible to supersize the American dream (the common use of the verb supersize was itself notable). By 2005 the average size of all newly built houses reached 220 m2 (an area 12% larger than a tennis court), and the mean for custom-built houses surpassed 450 m2, equivalent to nearly five average Japanese dwellings. 17 Houses in excess of 600 m2 became fairly common, and some megastructures of nouveaux riches covered 3000 m2 or more.

All these homes became crammed with consumer products ranging from miniature electronic gadgets to in-home movie theaters, from sybaritic marble bathrooms to granite-top counters in kitchens some of whose center islands were larger than entire kitchens in small European apartments. These new palatial villas came to be situated further from city downtowns and were reached by driving ever larger SUVs, vehicles connected neither to sport nor to any rational utility. There is surely no need for more than 1 tonne of steel, aluminum, plastic, rubber, and glass to convey one woman to a shopping center, but vehicles in common use weighed 2-3 t and in the case of the Hummer, a restyled military assault machine, nearly 4.7 t. Ownership of these improbably sized vehicles became the ostentatious symbol of the decade, whose other marks of excess were ubiquitous gambling and mass addiction to (not uncommonly drug-fueled) performances of televised baseball or fake wrestling.

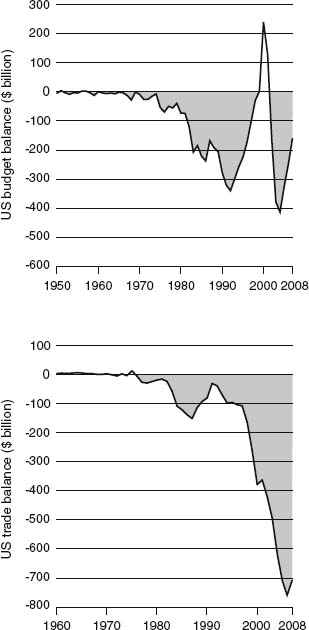

Although the decade saw a temporary reversal of governmental budget deficits (from a shortfall of more than $220 billion in 1990 to a surplus of nearly $240 billion in 2000), this relief was accompanied by steady increases of trade deficit that quadrupled from $111 billion in 1990 to $455 billion in the year 2000. 18 But at the beginning of the new century the U.S. economy appeared to be relatively invulnerable: after all, it had created the world’s “only remaining superpower.” That all changed in a matter of hours on the morning of September 11, 2001, but it is too early to tell if that attack on the iconic buildings of America’s economic and military might accelerated the American retreat or actually postponed it.

The swift toppling of the Taliban regime in Afghanistan and the launching of a (grandiosely named) global war on terror were essentially defensive/retaliatory reactions, yet they almost instantly strengthened the notion of America’s premeditated imperial behavior. Martin Walker, a journalist who worked for the Guardian and UPI, wrote (seemingly unaware of precedents) that “the new-Rome analogy that began as a journalist’s flippant conceit more than a decade ago has flourished into a cliché, and I’m now feeling a degree of remorse” (2002, 37). He explained that his writings on the parallels between ancient Rome and America had their origin in a talk he had with Adam Michnik, a Solidarity activist, at a conference in Moscow in 1989, a month before the Berlin Wall came down.

A list of (superficial and questionable) similarities between Rome and America that they discerned included culture that is robust and populist yet deferential (to, respectively, the Greeks and the Europeans); roads and highways; and a “common obsession with central heating and plumbing.” A few years later Walker returned to the topic in a book (1994), and he revisited it again in 2002:

The case for the analogy is easily stated. The U.S. military dominates the globe through 200 overseas bases, a dozen aircraft carrier task forces, and a unique mastery of the new high technology of intelligent warfare. This universal presence is buttressed by the world’s richest and most technologically advanced economy, which itself dominates global communications and the world’s financial markets, their main institutions based—and their rules drafted—in Washington and New York. (2002, 36)

This is a standard recital, but Walker (2002, 37) also made an acutely correct observation: “The comparison is as glib as it is plausible, and there has always been something fundamentally unsatisfactory about it.”

Such doubts have not crossed the minds of literati from across the entire intellectual spectrum who began to fill their books and essays (Bacevich 2002; 2003; Bacevich and Mallaby 2002; Ikenberry 2002; Wade 2003; Cohen 2004; Falk 2004; Johnson 2004) with imperial (and that often meant Roman) allusions and parallels. Of course, not everyone brought in the ancient parallels. For example, Ikenberry (2002) made no Roman comparisons. Similarly, Bacevich and Mallaby (2002, 50), while welcoming a newly found readiness to consider American empire on its own merits and acknowledging that “the notion that the United States today presides over a global imperium has achieved something like respectability,” found little to connect it to any predecessors; they saw America as a uniquely “informal empire” and “an empire without an emperor.”

But there has been no shortage of commentators who drew imperial parallels. Litwak (2002, 76) began his essay by noting that “America’s global dominance prompts popular references to a latter-day Roman Empire.” Joseph Nye, dean of Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, summarized the key points of this book The paradox of American Power (2002b) in an Economist article titled “The New Rome Meets the New Barbarians.” Unequivocal about the degree of U.S. dominance, Nye was apprehensive about the eventual outcome: “It is true that no nation since Rome has loomed so large above others, but even Rome eventually collapsed.”

Appraising the analogies of the two most often repeated factors in the Roman demise, internal decay and “a death of thousand cuts from various barbarian groups,” Nye did not see anything pointing strongly in the direction of internal decay but thought it was harder to exclude the barbarians, “particularly given the rise of transnational domains and the possibility of massive destructive power in the hands of small groups.” His conclusion: “The paradox of American power in the twenty-first century is that the largest power since Rome cannot achieve its objectives unilaterally in a global information age.”

Writing in New Perspectives Quarterly (2002), Paul Kennedy, a professor of history at Yale and the author of a widely read book, The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (1988), shared Nye’s opinion of America’s status as “the greatest superpower ever” but evoked Rome only by citing Rousseau’s question, “If Sparta and Rome perished, what state can hope to endure power?” His concern about the future was primarily economic because “America’s present standing very much rests upon a decade of impressive economic growth.” He concluded that if this growth dwindled and budgetary and fiscal problems multiplied over the next 25 years, “the threat of overstretch would return.”

In June 2002, Lind noted in the Globalist that comparisons between the United States and the Roman Empire were coming from both the right (Max Boot of the Wall Street Journal calling for a “benign” American imperialism) and from the center left, from commentators he called “humanitarian hawks” who were anxious to launch preemptive attacks to destroy hostile regimes. Indeed, empire allusions were made by writers as different in their viewpoints as Charles Krauthammer, a conservative columnist for the Washington Post, and Gore Vidal, a doyen of America’s liberal thinkers. 19

Institutional opinion makers partial to imperial analogies spanned a similarly broad range. The left-of-center New York Review of Books published in its February 28, 2002 issue David Levine’s caricature of President Bush in legionnaire’s garb carrying the scales of justice in his right hand and the presidential shield (behind which protruded an assortment of tiny rockets) in the other. This is art truly in the spirit of that great Soviet satirical weekly, Krokodil, whose cartoonists depicted U.S. presidents with rockets and bombs sticking from their pockets. 20 Yet another Levine caricature, in the issue of October 23, 2003, New York Review of Books portrayed the president in a modern flight suit but clad in a Roman mantle and plumed Roman helmet (cassia), a pistol tucked in his belt, right hand ready to draw, left one holding a miniature missile.

The unswervingly conservative Heritage Foundation invited J. Rufus Fears, a professor of classics, to give a lecture on the lessons of the Roman Empire for America. He claimed that “Rome of the Caesars and the United States today are the only two absolute superpowers that have existed in history” and concluded with a flatteringly inspirational comparison:

So we must ask ourselves the question: Are we willing to follow that path of empire? Do we have the reserves of moral courage that the Romans did to undertake that burden of empire? And what will be our legacy? For I am quite convinced that of all the people who have passed through the Middle East, of all the people who have passed through history, there has been none so generous in spirit, so determined to leave the world a better place, and so imbued with the technology and the wealth and the opportunity to leave a legacy far more enduring and far better than that of the Romans. (2005, 8).

But great-power analogies were not the only ones that captured American attention; soon came the talk of another imperial fall. The economic gains of the 1990s were rapidly transformed into economic worries as the runaway stock market retreated in 2000 and the threat of terrorist attacks introduced new uncertainties. The U.S. budget balance turned from surpluses of $237 billion in fiscal year 2000 and $127 billion in 2001 to deficits (figure I.6); in fiscal year 2008 the deficit approached half a trillion dollars ($455 billion), and the stimulus spending designed to reverse a major economic downturn pushed the deficit well above $1 trillion for fiscal year 2009.

Concurrently, the country’s trade deficit widened from $455 billion in 2000 to $787 billion by 2008 (see figure I.6). 21 At the same time, income inequalities, after narrowing for a time, began to widen during the last three decades of the twentieth century. Between 1966 and 2001 the median U.S. income rose by 11%, but the increase was 58% for people in the 90th percentile and 121% for those in the 99th percentile (Dew-Becker and Gordon 2005). The fraying of the middle class has certainly been the most worrisome consequence of this trend (Lardner and Smith 2005).

America’s double deficit: budget (1950-2008) and trade (1960-2008) balances. Plotted from data available at Office of Management and Budget, the White House.

Corporate scandals that involved fraudulent business deals and frank embezzlement (exemplified by Enron’s Kenneth Lay and Tyco’s Dennis Kozlowski and, ultimately, by Bernard Madoff) reached into billions, even tens of billions of dollars. This all began to evoke images of Roman excess. Here is a typical encapsulation (2009) of these analogies from the Web site Roman Empire—America Now!

Why is America now like the Roman Empire? Because it’s conquering the world? No. Because Americans are like Romans? Some are; some are like the Roman Senators of the fifth century, one of the most rapacious and ruthless ruling classes that ever held power. Think Mafia. For the amount of wealth: think billionaires today. . . . The Roman Empire fell because it was bankrupted by its leaders; well, look at the red ink now! Budget deficits, trade deficits, a huge national debt. . . . Does anyone remember when we were actually paying down the debt? Both Romans and now Americans have had the misfortune of being ruled by a Selfish Class. Rome fell because of it. Will America replay the Fall of Rome?

Given the often reflexive anti-Americanism of European intellectuals, it is hardly surprising that after 9/11 they eagerly added to comparisons of Roman and American transgressions. When Freedland (2002a; 2002b) was making a documentary film on the topic, he found “without exception” that Britain’s leading historians of the ancient world were “struck by the similarities between the empire of now and the imperium of then.” And when promoting the broadcast in the Guardian, that great standard-bearer of the British left, he came up with a clever title “Rome, AD . . . Rome, DC?” and wrote that “the word of the hour is empire,” that “sole superpower” is an “oddly modest” term to label America’s new imperial role, and that “the idea of the United States as a twenty-first-century Rome is gaining foothold in the country’s consciousness.”

Freedland ran through a predictable list of the similarities between the two empires, starting with overwhelming military strength and conquering and colonizing habits (albeit in America’s case “we don’t see it that way”). His list included superb road systems (he claimed that today’s information superhighways are the counterpart of Roman viae); a mixture of hard and soft power used in advancing the imperial design (togas, baths, and central heating as the tools of “enslavement” deployed by the Romans, and Starbucks, Coca-Cola, McDonald’s, and Disney as America’s “similarly coherent cultural package” used to dominate the world); and reliance on puppet governments (U.S. support for the Shah as a signal example). He also found both states adept at mythologizing the past and invoking supreme powers (deifications of emperors, “God bless America” at the end of political speeches, “In God We Trust” on the currency) and sharing the belief in “a mission sanctioned from on high.”

Less predictably, Freedland concluded that the gladiatorial games in the Colosseum and Hollywood shoot-’em-ups serve the same function (“Both tell the world: this empire is too tough to beat”), and searching for a historical analogy to a recent atrocity, he suggested that Romans had their 9/11 when a Pontic king, Mithridates, implored his subjects to kill the Romans across Anatolia in 80 B.C.E. and they massacred some 80,000 people. Such a list should make even readers only slightly familiar with Roman and American realities highly suspicious of the appropriateness of the comparisons. Leaving aside the left-leaning opinions of most of Hollywood’s producers and celebrities, what insight is gained by confusing Hollywood movies with U.S. policy? And how meaningful is a comparison between an indiscriminate slaughter of a population seen as an occupier in a time of war and an ideologically motivated terrorist attack on carefully chosen symbols of a superpower?

Peter Bender, one of the doyens of German journalism and international studies, identified two great resemblances between ancient Rome and the United States as similar paths to dominance and historically unprecedented positions as world powers of their time. He detailed his thesis in Weltmacht Amerika das neue Rom (2003a). English readers can get all of its principal arguments in a paper that Andrew I. Port of Yale translated for Orbis (Bender 2003b). Bender’s approach differs quite a bit from Freedlander’s, and he is careless in claiming that “the Roman Empire included almost the entire then-known world; the United States dominates almost the entire globe since the collapse of the Soviet Union” (Bender 2003b, 145). I deconstruct both these assertions in chapter II.

Bender put a great deal of emphasis on geopolitics. 22 Most notably, he saw a formative commonality shared by Italy and the United States: both should be seen as insular nations. Obviously, they are not islands, but Bender claimed that because of their long coastlines their history has been molded more by the fact that they are surrounded by seas rather than by interactions with their neighbors. As a result, both Romans and Americans “were for long time insular in their thoughts and feelings” (Bender 2003b, 146). On the question of why both abandoned this insularity, Bender conjectured that they did so once “the oceans ceased to offer protection, or so it seemed” (2003b, 148). For the Romans that moment came during the First Punic War, for the United States it was the Pearl Harbor attack. A third similarity is that neither empire was created by a great conqueror (a charismatic leader, in the modern parlance); their power increased gradually but steadily until they became dominant.

A new chapter of imperial comparisons was opened by the U.S. invasion of Iraq in March 2003. A swift conquest was followed by a seemingly endless sequence of killings by suicidal al-Qaeda bombers and sectarian militias as well as by criminal and extortionary gangs. By the end of 2007 this quotidian violence was responsible for deaths of nearly 4,000 U.S. soldiers, tens of thousands of Iraqi police and military, and of a much disputed but undoubtedly high number of civilians. 23 These years of violence produced nothing better than a bloody stalemate, exposed the limits of U.S. military power, and abruptly shifted the perception of America as an ascending empire to America trapped in a painful, costly, and eventually futile effort to prevent its loss of great-power status. As the Iraq stalemate continued, the new imperial analogy was supported as much by the similarities of once seemingly invincible great-power superiority as by the expectations of impending retreat from that unique status.

The image of America as a great power—a state with many enemies but, much as the Roman Empire, with no equal, a dynamic society with fabulous domestic riches, organizational ingenuity, and aggressive drive—was replaced by impressions of a society slowly coming apart under the stresses of Islamist attacks and Iraqi “quagmire” (a favorite term that defeatists borrowed from the Vietnam War era). By 2006 talking heads and op-ed writers were eager to prophesy the end of American empire in the sands of Mesopotamia. Adding to the perceptions of America in its twilight phase was the insidious “takeover” of the country (as some saw it) by tens of millions of new “barbarians” flooding across the country’s borders as well as such home-grown signs of decay as gross obesity, rising debt, and runaway trade deficits.

The opinion-making chorus began to intone in a near unison: an empire that is unmistakably in decline. And once the idea of decline gains broad acceptance, the notion of fall cannot be far behind. This reasoning may turn out to be yet another fine illustration of a logical fallacy that the Romans knew as post hoc, ergo propter hoc (after this, therefore because of this). On the other hand, it might be an accurate anticipation of events because decline does usually precede fall. Not surprisingly, some European commentators firmly believe that the latter is the correct interpretation, and they have been eager bearers of the message.

Both the elite and public perceptions of U.S. actions and verdicts on America’s future became highly negative, even hostile, in the two greatest continental powers, Germany and France, as well as in most of the smaller nations. Of course, antiAmericanism is nothing new in France—for example, Julien (1968) wrote about American empire 40 years ago—and after 2003 the sentiment found unusually widespread acceptance everywhere in Atlantic Europe. In Italy, Viansino (2005) published an explicit comparison of impero romano and impero Americano, and Italians familiar with the history of the Roman Empire have been eager to contribute their condemnations in an online discussion of U.S.A. e Impero Romano on the Web site Forum di Riflessioni.

Russian accusations of America’s imperial intents, honed to perfection during the Stalinist years and toned down by the late 1980s, made a strong comeback under Putin. Even Mikhail Gorbachev, who presided over the demise of the Soviet empire, sees it that way. In a BBC interview in June 2007 he said,

We lost 15 years after the end of the Cold War, but the West I think and particularly the United States, our American friends, were dizzy with their success, with the success of their game that they were playing, a new empire. I don’t understand why you, the British, did not tell them, “Don’t think about empire, we know about empires, we know that all empires break up in the end, so why start again to create a new mess.”

Many American commentators concurred. Weigel (2007, 1), asking if America is a new Roman Empire, answered, “Yes, obviously it is,” and noted that “our confidence leads us to make the same kinds of military blunders as the Romans, and the only argument is whether Iraq is our Teutoburg Forest or our Adrianople—if we’ve learned our lesson and will stop pushing outside our boundaries, or if we’ve used up all our get-out-of-jail cards and are primed for a fall.”

An editorial in Financial Times, August 18, 2007, was nearly as gloomy:

Comparisons with Rome’s later periods of imperial excess and hubristic over-expansion are more popular. Some point to Rome’s institutional decay. . . . Others dwell on its military misadventures, in particular the perennial failure to subdue Mesopotamia. . . . The question “Are we Rome?”—long a national fascination—has become shorthand for “Are we doomed?”

But the editorial offered a way out:

Rather than lamenting a slide into decadence, the U.S. could remind itself of strengths it shares [with the Roman Empire]—social mobility, an ability to assimilate newcomers of different races, and a talent for making life pleasant for its citizens, whether with aqueducts or circuses.

A similar recipe for preventing decline was offered by Cullen Murphy in Are We Rome? (2007). The book’s overall tilt and tone are clear from its subtitle: The Fall of an Empire and the Fate of America, and from the précis on the cover flap, which claimed revelations of “a wide array of similarities between the two empires: the blinkered, insular culture of our capitals; the debilitating effect of venality in public life; the paradoxical issue of borders; and the weakening of the body politic through various forms of privatization.”

Murphy found six principal parallels between the two states: as centers of the world; as military superpowers; as states poorly served by privatization of public services, beset by corruption in government and degradation of civil society; as polities ignorant and dismissive of the outside world; as states with major border problems; and as societies that find it impossible to manage their overwhelming complexity. Nevertheless, he summoned a vigorous dose of American optimism that made him see a fundamental difference between Rome, which “dissolved into history just once” (albeit successfully, given its heritage), and America, which “has done so again and again”:

The genius of America may be that it has built “the fall of Rome” into its very makeup: it is very consciously a constant work in progress, designed to accommodate and build on revolutionary change. . . . Are we Rome? In important ways we just might be. In important ways we’re clearly making some of the same mistakes. But the antidote is everywhere. The antidote is being American. (206)

I find this faith breathtaking: Americans making all those mistakes that can be avoided by being American.

The Comptroller General of the United States David Walker joined the argument by using the parallel of decline:

The Roman Republic fell for many reasons, but three reasons are worth remembering: declining moral values and political civility at home, an overconfident and overextended military in foreign lands, and fiscal irresponsibility by the central government. Sound familiar? In my view, it’s time to learn from history and take steps to ensure the American Republic is the first to stand the test of time. (USGAO 2007, 11)

This survey of recently published imperial analogies and parallels could continue, and such writings will keep on appearing. Moreover, on the Internet, one can find every kind of imperial comparisons, questions, warnings, and dire prophecies— laudatory, condemnatory, condescending, inspirational, pretentious, ignorant, officious, incoherent, facetious (Latin adjectives all)—on Web sites and chat rooms like American Empire, The American Empire Project Forum, America Is the New Rome, and Roman Empire—America Now! By mid-2009 a Google query for “American Empire” elicited more than 29 million hits, and “End of American Empire” came back with more than 22 million. 24

But there is one group of Americans who do not think their country is the new Rome. America’s conservative premillennial Protestants—the label Herman (2000) used for those who believe in the Bible’s literal truth and the coming end of time— take strong exception to the idea; instead, they see a unified Europe as a new Roman Empire. They believe that the Revelation of John mandates the revival of the Roman Empire: “Five kings have already fallen, the sixth now reigns, and the seventh is yet to come, but his reign will be brief” (Rev. 17:10; Arterburn and Merrill 2004 translation). Egypt, Assyria, Babylon, Medea-Persia, and Greece are interpreted as the five fallen kingdoms; Rome was the ruling power when John’s vision took place; and a revived Roman Empire is yet to come, which will be ruled by a trinity of Satan, Antichrist, and Beast.

Many fundamentalists believe that the reunification of Europe—starting with a highly symbolic Treaty of Rome in 1957, which set up the European Economic Community, and progressing to the European Union, which stretches from the Atlantic to Russia’s borders—constitutes a clear step toward the fulfillment of that prophecy. Curiously enough, a 2004 exhibit in Brussels that was coordinated by the European Commission and sponsored by the European Council, openly affirmed the goal of a new Rome (sans the Satan part, naturally). Its organizers articulated the European Union’s ambition in a remarkably uninhibited way: the euro will break the monopoly of the dollar by 2010, and the Roman Empire will return as the EU expands deep into Eurasia, North Africa, and the Middle East and becomes the world’s premier superpower and the dominant force in global affairs because of its vast legal and moral reach (Evans-Pritchard 2004).

From a historic point of view, these sentiments, combining quasi-Napoleonic hubris 25 and reflexive anti-American animus, are much easier to understand than the reasoning of American fundamentalists. Those exegetes equate opaque biblical phrases (“And he was given authority to rule over every tribe and people and language and nation” (Rev. 13:7)) and mythical creatures (the Beast with “two horns like a lamb and spoke like a dragon” (Rev. 13:11-14)) with the process of European unification and with the diabolical powers of Brussels bureaucrats (Figure I.7). How they arrive at such interpretations is a mystery to which only they possess a key. In any case, many (most?) of the 31% of Americans who believe that the Bible is the actual word of God to be taken literally may have no problem in accepting these conclusions. 26

A leading American prophecy writer, Hal Lindsey, had no doubt that the Anti-christ would emerge “out of the culture of the ancient Roman Empire” (1970, 113) to lead Europe into its final battle, in which it would be defeated by the returned Jesus and “and there will be no more death or sorrow or crying or pain. For the old world and its evils are gone forever” (Rev. 21:3-4). Ever since, many writers espousing biblical inerrancy have foretold the emergence of the Antichrist from the EU: Meredith (2004), Rast (2003), and Gillette (2007) exemplify these convictions. Their reasoning echoes the Church of God Daily Bible Study explanation that describes “the New Rome, the real Rome, which will be based in Rome (that’s what Roman Empire means)” as “the very formidable opponent of the USA in the end of time—which is not theory or conjecture . . . war with the EU will be an unavoidable clash of titans”; the new “Roman Empire will get much of its military and religious power from Satan . . . that is reality, based upon the whole history” (Blank 2004, 1).

Detail of the seven-headed beast in Dürer’s rendering from his 1498 woodcut series illustrating the Revelation of St. John (Apocalypse). All of Dürer’s woodcuts can be found in Kurth (1927).

This book is for those with whom I share an inadequate power of imagination to equate the EU with a beast risen up out of the sea (with “seven heads and ten horns, with ten crowns on its horns” (Rev. 13:1)) and hence to state with confidence that the pursuit of Roman-U.S. analogies is an entirely misplaced endeavor because a new Rome has already risen on another continent. As noted in the preface, the recent ubiquity of imperial analogies between Rome and America could be dismissed as merely a fashionable bandwagon, but the comparison of the two states is not entirely inapt, and its validity (or invalidity) deserves a closer critical look. The best way to explain why America is not a new Rome is not a direct approach, not, as the Romans would have said, jumping in medias res by offering a list of major putative differences with apposite comments.

A better way to pursue this task is by following the Lucretian advice that I chose as the epigraph of this book: by establishing first many a truth and approaching the heart of the matter by a winding path. Several reasons make this approach necessary. Perhaps most notably, the ground must be prepared because America’s understanding of a society whose apogee came nearly two millennia ago is a simplistic caricature fed by Hollywood extravaganzas and repeated phrases about military overextension, imperial excesses, and decline and fall.

Europeans should have a somewhat richer understanding of Roman realities, but when they, and the Asians, make the imperial comparisons involving the United States, their judgments are all too often no less questionable. America’s commonly simplistic image of the outside world and of the distant past finds a worthy counterpart in the outsider’s endless biases concerning America. This glibly professed European and Asian understanding of the United States is particularly exasperating, even infuriating, because it does not stem from simple ignorance or a lack of information but is so often rooted in a mixture of condescension, disdain, and even hatred mixed with envy. 27

In the quest for a better understanding of Roman matters, all but a tiny share of Americans (as well as other speakers of non-Romance languages) share a disadvantage that can be fixed only by years of dedicated learning and a lifetime of devotion: the intricate, disciplined, parsimonious yet extravagant lingua Latina does not speak to them. This is, of course, only part of a much larger missing parcel: linguistic innocence is an American norm that extends even to the astonishingly inadequate Arabic and Farsi capabilities of the U.S. government’s intelligence agencies. As a result, even the simplest of all Latin words, et, is constantly and inexplicably mispronounced by legions of opinionated TV experts as “ek.” 28

No less important, for all but a small fraction of Americans the names on the map of the Roman world evoke no recognition and carry no meaning; they are nothing but alien terms unconnected to any recognizable features (be they of a mundane or magnificent aspect). They do not produce images of natural grandeur (such as erupting volcanoes or gales checking the flow of a mighty river, both so memorably described by Lucretius), 29 or recall admirable achievements of bold engineering designs (tall arches of the Aqua Claudia marching unswervingly across the Roman Campagna would be an excellent example). Only the names of a few cities resonate, but how many would those be besides Rome itself, Pompeii, and perhaps Carthage and Alexandria? How many Americans know of the importance of Augusta Treverorum or Dura Europos? 30

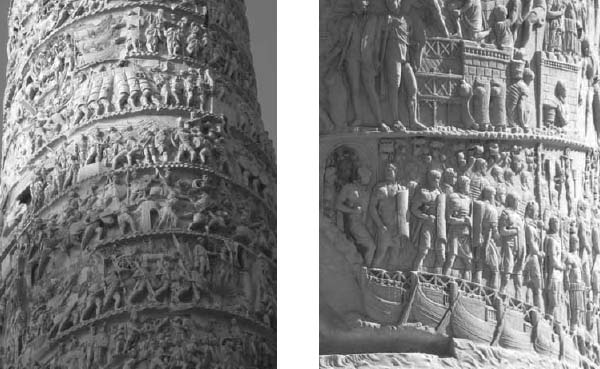

Details of Trajan’s column (completed 113 C.E.), a 30-m tall structure on an 8-m pedestal base, built of 20 Carrara marble drums and decorated with a 190-m winding frieze commemorating the emperor’s Dacian wars (101-102 and 105-106 C.E.). Photo by V. Smil.

I suspect that among the scores of experts who virtually live on the screens of ponderous political TV shows and who casually mention Roman-American parallels hardly anyone could locate the forests of Tarraconensis, the fields of Paphlagonia, and the shores of Syrtica on a blank map of lands surrounding mare nostrum (as Romans proprietarily called the Mediterranean). 31 And how many of them command any Braudelian longue-durée perspectives or have a secure understanding of key historical realities? How many editorial writers (now joined by masses of utterly unqualified bloggers) who pontificate on America’s decline and Rome-like fall could confidently say which emperor came first—Trajan, whose victories in Dacia are commemorated on a splendid marble column that the Roman senate ordered to be built on his forum (Figure I.8), or Marcus Aurelius, who set down (in idiomatic Greek) his Stoic thoughts while defending the empire’s northern border among the Quadi at Granua?

Three generations ago a fairly solid knowledge of these matters was still de rigueur among European intellectuals, but it is no longer so in the EU of the early twenty-first century, and I have no illusion that the unprecedented numbers of European tourists visiting Rome take home any better appreciation of Roman history. Noting these weaknesses in basic understanding (lacunae is a fitting Latin word here) is not a matter of pedantic and irrelevant insistence on trivia or marginalities whose grasp (or lack of it) has no bearing on one’s ability to understand and comment on Roman matters, to interpret their meaning and import, and to use them in historic analogies. The opposite is true: an appreciation of the language, a feel for the lay of the Roman lands, a solid grasp of the glories and blunders of the empire’s long history are among a few quintessential markers of necessary Latin/ Roman/imperial homework well done.

In their absence it is not surprising that so many commentators can get away with trotting out obvious, generic realities as if they were brilliant, insightful observations; unfortunately, most of their readers, viewers, or listeners apparently take this verbal fluff for learned Roman-American analogies. And even more exasperating is the casualness with which the instant experts put together a few vague analogies about habits, preferences, or trends in two societies separated by two millennia in time and conclude that these will bring about similar long-term outcomes.

In this brief book I confirm the limited validity of some of these parallels, but its main aim is to diligently deconstruct most of that misleading comparative edifice that pictures America as a new Rome. I try to convey the complex and contradictory nature and achievements of the two great societies. I point out some valid parallels and similarities as well as fundamental differences.

In the second chapter I first explain the meaning of empire and assess how the U.S. realities do not fit the definition. This is followed by contrasting the territorial extents of the two states and by the examining America’s peculiar global hegemony. In the third chapter I compare the inventiveness of the two societies and the power of their prime movers and energy sources. The fourth chapter focuses on the vastly different population dynamics of the two societies, on their experiences of illness and health, and on their distinctive patterns of wealth and misery. Finally, in a brief closing chapter I reassess the most commonly cited similarities between the two societies and recapitulate those fundamental differences that make Roman-American historical analogies dubious.

The Romans had an apt phrase, proverb, or poetry line for everything. Homines libenter quod volunt credunt (men believe what they want to), wrote Terentius; and Seneca said that fallaces sunt rerum species (the appearances of things are deceptive). While it may not be possible to change the first reality, I try my best to go beyond surficial and deceptive appearances in order to clear away some misconceptions and fallacies and to demonstrate that America is not a new Rome. That is actually an easier task than to be able to say, with some certitude, what modern America is. Marcus Tullius Cicero knew that state of mind well: Utinam tam facile vera invenire possem quam falsa convincere (I only wish I could discover the truth as easily as I can uncover falsehood).