Knock him about the sconce with a dirty shovel: (Hamlet).

Act I: The Finder’s Story.

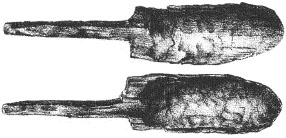

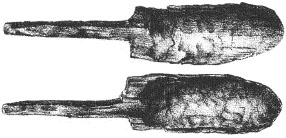

IN THE SUMMER of 1953, my last term at school, I was sitting in the Manchester Central Reference Library. I should have been annotating Wecklein’s edition of Aeschylus’ Agamemnon, but had become engrossed in Dr J. D. Sainter’s The Jottings of some Geological, Archaeological, Botanical, Ornithological and Zoological Rambles round Macclesfield: (Macclesfield 1878). Page 47 had me hooked. It described the recent finding by miners of a number of grooved stone hammers, or mauls, in an old surface working, “from three to four yards in depth”, near the copper mines at Alderley Edge, where I lived and had grown up.1 The hammers were quite distinctive. They were used as doorstops in the cottages and farms of the area, and I had found three myself on the Edge. (In later years, I learnt that identical artefacts are common where early metal-working has taken place. Those that I have handled, in Ohio and in Armenia, were all in a Chalcolithic context.) What was so interesting about Sainter’s record was that among the hammers lay “an oak shovel that had been very roughly used”. Sainter illustrated the shovel, back and front, opposite page 65, and to my excitement and bewilderment I knew that I had seen that “shovel”, and seen it often. But couldn’t remember where. I knew only that it was familiar.

Days later, in the way that such things happen, I was thinking about something else when I “saw” the “shovel” and where it was. I rushed to Alderley Edge Council School and cornered the headmistress, Miss Fletcher, who had taught both me and my father, and cried: “The shovel in Miss Bratt’s room! Where is it?” Miss Fletcher, used to my manic ways, said: “I don’t know, Alan. Let’s go and look.” We went to Miss Bratt’s room, a nineteenth-century Gothic gaol, where I had been incarcerated in my second year of the Infants’ Department at the age of six. Sainter’s shovel had hung on the wall, immediately to the left of the door, next to a cupboard. The wall was blank, but the hook was still there.

“I remember there was something,” said Miss Fletcher. “We’ll ask Mr Ellam.” We found the caretaker. “Oh, ay, there was summat of the kind, wasn’t there?” said Billy Ellam. “But we had a big sort out when Twiggy retired, and most of it went on the tip.” “You couldn’t!” I yelped. “I’ll tell you what,” said Billy Ellam. “If it’s not on the tip, it’ll be under the stage in the hall.”

I squeezed into the twelve-inch gap below the stage, lighting my way with Billy Ellam’s torch. The space was filled with coconut matting, high-jump posts, Miss Bratt’s fire-guard (we still use it at home as a towel rail), baskets, boxes, hoops, balls: all the clutter of a village school. I was lost to sight, and Miss Fletcher called anxiously after me, but I persevered, turning everything over systematically, in this exercise in educational speleology. Soon contact with the outside world was lost, as I worked my way into the dark. And, at the end of the understage crevice, the last object there, I found the “shovel”, with the label identifying its provenance still (just) adhering. There was no room to turn around. I had to find my way back blind, pulling with my toes and pushing with my one free hand.

“Well!” said Miss Fletcher. “I think it’s finders keepers. I’ve never seen anything like that performance in all my born puff!”

I took the shovel to the Manchester Museum, but did not get past the desk. Despite my protestations, there was “no one available to comment”.

So it began. I knew, from experience, my parents’ habit of disposing of anything they didn’t understand, or think of worth, and that compelled me never to leave the “shovel” at risk. It went with me all through the army, occupying the centre of my kit bag.

The British Museum declared it “possibly a Tudor winnowing-fan”.

It was with me at Oxford. The Ashmolean was not interested and promoted it to a “child’s toy spade: Victorian”. The conditions of its finding were ignored. I stopped. There were other things to be done. So I kept the Tudor winnowing-fan and Victorian child’s spade safe and bided my time. I knew instinctively and later intellectually, that the object was of considerable archaeological importance and trusted that one day I should find the sympathetic ear.

Eventually, the ear belonged to Dr John Prag. I baited the trap with some “Celtic” stone heads, for the recording of which he was responsible at Manchester. He came to see the two that I had. I showed him the shovel. The trap was sprung. And I shall never forget the sense of achievement as I formally put the shovel into his hands and care. The rest is prehistory.

I remain awed by three aspects of the matter: the tenuousness of the thread of survival; the unscholarly attitude of many archaeologists, who seem to work on the principle of, “If I don’t comprehend it, it can be of no significance”; and the importance of the human ageing process.

I had not changed my story since I was eighteen years old. It seems a pity that we have had to wait forty years before I was sere enough to approach with any authority the university I had tried first. And I was fortunate in meeting the open mind of a John Prag. In my tetchy dotage I would urge all archaeologists not to dismiss the young. They do, at least, have better eyesight; and are capable of squirming through the lumber of a village school.

JOHN PRAG, The Manchester Museum

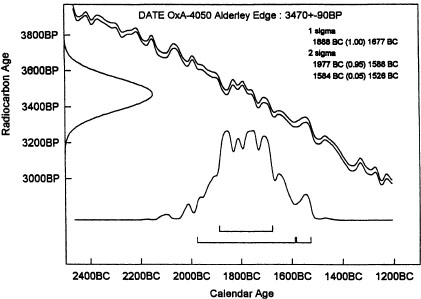

1991.85. Wooden spade: the blade long and narrow with a steeply rounded end; one side of the blade missing, and an old split running with the grain between this break and the handle. The handle is short, and tapers to a point: possibly part of it split away, ? in antiquity. Probably oak. Max. total length 59.4 cm, length of blade 33.4 cm; max. length of handle 26.5 cm; max. extant width 12.3 cm. From excavations at Alderley Edge, 1875: presented by Alan Garner. Thought by Boyd Dawkins to be Bronze Age: dating confirmed May 1993 by accelerator radiocarbon dating OxA-4050 as 3470 + – 90 (uncalibrated) BP 1520 + – 90 BC, which, when calibrated, gives a range 1888-1677 cal BC.

(From the Manchester Museum Accessions Register)

The date copper was first mined on Alderley Edge in Cheshire has long been a matter for speculation. Archaeologists (as opposed to mining historians) have generally leaned towards the Bronze Age: the date was first proposed, tentatively, by the Manchester geologist and prehistorian, Professor William Boyd Dawkins, who visited the site in 1874, when the Alderley Edge Mining Company Ltd. were carrying out clearance work prior to opening new adits at Brynlow on the south slope of the Edge, and who then carried out a further investigation of the site. The miners, like many local people before, and like Boyd Dawkins and his successors Darbishire, Roeder, Graves and many others, found great numbers of grooved sandstone hammers, and it was apparently simply on the basis of their crudeness that Boyd Dawkins suggested that the mines must be early, and therefore of the Bronze Age. Similar arguments have been put forward for other sites in Britain and elsewhere, where independent evidence has nearly always been lacking. The question was reconsidered in Current Archaeology 99 by Paul Craddock, who noted that at least two recent writers had cast serious doubt on the prehistoric date for Alderley and other sites, on the grounds of insufficient evidence (C. S. Briggs, PPS 49, 1983, and G. Warrington, “J. Chester Arch. Soc. 64, 1981”); Briggs went so far as to reject the Bronze Age C-14 date achieved for the Mount Gabriel mines (County Cork), on the grounds that it was from a single sample in a potentially confused context.

Neolithic flints have been found on Alderley Edge, but no securely Bronze Age artefacts. In 1991 a Middle Bronze Age palstave was found in a garden in the area known as the Hough below the north side of the Edge; at the same time Alan Garner rediscovered another palstave that had been found in 1936 at Common Carr Farm, on the plain a mile and a half to the northwest of the mines. Both find spots suggest these bronzes may have been deposited as offerings in springs or pools, and they need have no direct connection with the industrial activity above.

The mines themselves have been extensively worked in the post-medieval period, from the late seventeenth to the early twentieth centuries and, particularly in recent years, have attracted a great number of visitors and not a few vandals, so that the chances of finding evidence for early mining around the shafts are slim. Not surprising perhaps, that the Manchester Museum, as well as a large collection of stone hammers from Alderley Edge, possesses an object labelled rather confusedly as a “Stone Age iron pick” (in fact identified as Roman in 1905 by its finders, Roeder and Graves, and most probably from a nineteenth-century drill bit).

In 1979 a team from the Manchester Museum, funded by the Manpower Services Commission, carried out a new survey of the Edge, complementary to the cataloguing of the Museum’s prehistoric collections, but the plan to section one of the “ancient” working hollows in order to retrieve samples for carbon-dating came to nothing for lack of funding and because of a change of direction by the MSC. In 1991 David Gale conducted exploratory excavations for Bradford University in two areas of the Edge, partly with a similar aim in view, but none of the organic material found was suitable as dating evidence.

There remains the mysterious shovel, found the year after Boyd Dawkins’ excavations and dismissed by Warrington as “of no significance for independent dating”. Indeed, he pointed out that wooden shovels were in use in the ore treatment works at Alderley at the time of its discovery.

As some miners were at work on the Edge, they came upon a large collection of stone implements, consisting of celts or adzes, hammerheads or axes, mauls, etc. from one to two feet below the surface . . . and others were left in some old diggings of the copper ore, from three to four yards in depth, along with an oak shovel that had been very roughly used.

So Dr Sainter in 1878, repeated by Roeder in the Transactions of the Lancashire and Cheshire Antiquarian Society for 1901; and (with the last illustration I have seen of the shovel) by William Shone in Prehistoric Man in Cheshire (1911). Since then it had vanished. It seemed to have become another of the legends of Alderley Edge. “If only I could find out what had happened to that shovel,” remarked David Gale, in wistful ignorance, as we rattled in an elderly train out to his first meeting with Alan Garner.

There are few moments in any museum curator’s life when he does not really believe he is seeing what is laid before him. One’s colleagues, more senescent, more cynical or just less gullible, tended not to believe it. Not, perhaps, a Tudor winnowing-fan, but very probably a peat-cutter’s spade, no older than medieval, they said. No one argued with the circumstances of the discovery, but the fact remained that the dating of evidence for that context, the stone hammers, were themselves not properly dated. The donor bravely agreed to our seeking a radiocarbon date for the shovel, and with the collaboration of Velson Horie, Keeper of Conservation at the Manchester Museum, we submitted an application to the Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit at the Research Laboratory in Oxford.

The rest is science. Although such shovels have been found in other “primitive” mining contexts, what is exciting for the archaeologist is not only that this one (an object of great interest in its own right because of its exceptional condition and unusual history) thus belongs to the Middle Bronze Age, but also that activity in the mines themselves can now be firmly dated at least to the Middle Bronze Age, and probably to the early part of that period. To judge by the great quantities and variety of the stone hammers that have been found, that Bronze Age activity must have been considerable.

Legends have a way of leading to the truth.

* * *

Act III: The Scientist’s Story.

RUPERT HOUSELEY, Oxford Research Laboratory for Archaeology

In September 1992 John Prag and Velson Horie approached me about the possibility of getting a radiocarbon date on a wooden shovel which had been donated to the Manchester Museum. On hearing about the Alderley Edge spade the thought crossed my mind “wooden objects seem to be in fashion” since only a few months before, I and my colleagues at the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit had been involved in dating a series of wooden objects: a wheel, longbow, a yoke and some bowls, from the collections of the National Museums of Scotland. When John Prag sent me a photograph of the object, I was struck by how similar it was to the peat-diggers’ spades I had seen in old pictures from the Somerset Levels. As to its age, who (or what) could tell?

The answer was to “what” rather than “who”, and it lay in the wood from which the shovel had been made. As all users of radiocarbon dating will know, the possibility comes from the fact that a living tree takes up 14C from the atmosphere and incorporates it into its growth rings. The atoms of 14C decay with time and from this we tell the age. By determining the date of the wood one arrives at an approximate value for the time of manufacture of the shovel, although, strictly speaking, the wood could have been worked into the form of a shovel any time afterwards.

Late in 1992, once we had heard that the dating would be supported under the programme funded by the Science and Engineering Research Council, the next set of things to do was to think about how much wood to take, from where it would be taken, and to decide whether there was any sign of past treatment by preservatives.

As Alan Garner has shown, although the “recent” history of the shovel was known, or could in part be inferred, what the original Victorian miners may have done to the shovel was not known, and so we had to assume a “preservative” may have been applied to prevent its disintegrating. It was partly to minimise potential problems from this that Velson Horie drilled into the shovel, discarding the outer discoloured surface, to collect one hundred milligrams. (![]() of a gram) of clean “saw-dust”. This proved more than enough for a date.

of a gram) of clean “saw-dust”. This proved more than enough for a date.

A reflux wash with organic solvents was added to cope with any residual amounts of potential preservative. This rounded off the process: the result is chemistry and physics.

The resultant date 3470 + – 90 BP (OxA-4050) puts the age of the wood firmly in the first half of the second millennium BC, the shovel into the Middle Bronze Age, and, by implication, the mining of copper back into the prehistoric past. All because of a chain of some rather improbable events.

1 This article, by Alan Garner, John Prag and Robert Houseley, was first published in Current Archaeology Number 137, March 1994. (For availability contact 9 Nassington Road, London NW3 2TX.)