SAM IS A 30-YEAR-OLD MALE WITH A CHILDHOOD TRAUMA history; he also was a veteran of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. He had been in therapy for 2 years by the time we met. At the time of this example, we had done yoga together for about 9 months. One day we were doing the Seated Mountain Form (see Chapter 8 for an example) together, and after a few minutes of sitting, Sam said, “My back feels really sore.” I responded, “Would you like to try standing up?” After a moment, Sam replied, “Yeah, ok.” We stood up together and I asked, “How does your back feel now?” Sam’s face changed from a grimace to a smile and he said, “Hey, it feels a lot better.” I then asked Sam if he wanted to try that action again and this time we could each experiment with noticing the muscles we felt that helped us move from sitting to standing. He was up for it. He was curious. So we sat back down and took a couple of breaths and then tried it again. My invitation was “if you like, moving a little more slowly this time, experiment with noticing whatever muscles you feel.” Once we stood up I asked Sam if he noticed any muscles and he said, pointing to the top of his legs, “I felt these big muscles in my legs just when I started standing.” I shared that I had noticed the muscles in the backs of my arms because I had pushed myself off of the arms of the chair to get started. Finally, I asked Sam again while we were still standing, “How does your back feel?” “Good, good,” he said.

From feeling and choosing to acting

In Chapters 2 and 3 we explored the essential trauma-sensitive yoga (TSY) practices of interoception and choice making. Now the key question before us is, what do we do once we feel something and/or choose to do something? For many traumatized people it is one huge challenge to notice a body feeling, another huge challenge to choose what to do with their bodies once they feel something and, perhaps the greatest challenge of all, to actually take an action based on what they feel in their bodies. To make this leap from feeling something and/or choosing something to doing something, one must trust one’s body as a useful, functional thing. But, as we have seen, to be traumatized is to live in a body that is more likely to feel useless and ineffectual. Immediately we can sense the dilemma. A traumatized body has been chronically acted on; it has rarely, if at all, been the agent. In fact, it is possible to suggest that in order to survive the kinds of ordeals that our clients have been through it really doesn’t make sense to the organism (and I use that word purposefully as I did in Chapter 3 because this may well not be a conscious choice, especially for people who are born into and/or grow up in abusive, chaotic environments) to continue to use energy at exerting its own will if it always fails. Perhaps energy is better spent just trying to survive. In order to heal from trauma, we must begin to do more than survive. We must reclaim our body as a successful agent of action and change.

Action, intentional action, and effective action

Taking action is a description of a larger paradigm, which has three components that I would like to describe. Once I have described them, I will resort to the term taking action but it will be understood that it represents some or all of the three components (as we will see, it is not required that all three components be satisfied in order for action taking to have therapeutic value). The three components are as follows:

• Action: Something you do with your body; something purely motoric

• Intentional action: Something you do with your body that is purposeful (based on an idea or feeling)

• Effective action: Something you do with your body that you notice results in feeling better physically

Action

Every yoga form offers an opportunity for action, that is, doing something with your body, though every action does not have to be intentional or effective. Consider the case example that opened this chapter. Sam’s action is to stand up. That is a purely motoric thing, which results in his moving his body from sitting to standing. There is a place in TSY and trauma treatment in general for simply acting, that is, doing something with the body, even if the action is not based on any idea. This happens when we choose to move our arms in one way and not another, for no particular reason. This phenomenon is purely motoric and doesn’t require any forethought or analysis. Just acting could, under certain circumstances, like in the context of a yoga form, be very therapeutic for some clients.

Intentional action

However, consider the example of Sam that opened this chapter. While Sam takes an action when he stands up there are other things going on that factor into our overall understanding of taking action within the context of TSY. Before standing, Sam noticed some discomfort in his back and he told the TSY facilitator what he was feeling. The facilitator’s response is the invitation to stand. So not only did Sam do something motoric but it was also preceded by his awareness of discomfort in his back and an invitation from the TSY facilitator. Once the facilitator made the invitation to stand, it became an idea to Sam (maybe an idea that standing might make his back feel better, we don’t really know, but at least an idea like “do I want to keep sitting or do I want to stand?”). Therefore, even though the idea to stand is presented at first as an invitation, Sam’s act of standing becomes an intentional action because it was done on purpose (based, ultimately, on some idea and/or body feeling of his own). In this equation, an action has to be purposeful to be considered intentional but it can originate from either the client or the TSY facilitator. As long as the client has a choice and is not compelled to act, he is the “owner” of the action once he engages in it.

Actions that are planned and carried out on purpose we call intentional actions. These occur any time we decide to do something based on what we feel: “my back is tight: I will stand” or “I would rather stand than sit right now” or “my legs feel strong: I want to use them to stand up.” Clearly, taking action based on these kinds of awarenesses can be very beneficial in the context of trauma treatment. In fact, this may be a very good definition of empowerment, which, as we have seen, Judith Herman encourages us to make a central part of trauma treatment.

It is also useful to compare action, taking action, and the other key part of TSY methodology discussed in Chapter 3: making choices. Action and intentional action as I have presented them are both the result of some kind of choice. More to the point, I would suggest that actions may be choice based or may not be (there are such phenomena as unconscious actions), but intentional actions are always choice based. By its very definition, an intentional action is one that requires a purpose, and purpose requires choice (I need to know I have options in order to do something purposefully). An intentional action is one that we choose to take no matter how obscure our purpose may be (we may know for sure what we want to accomplish by our action or we may have only a vague idea). Our work with TSY is to help our clients take as many intentional actions as possible.

Effective action

The third and final aspect of taking action is effective action, and it is different: it stands alone. Notice the next couple of things that happened after Sam took his intentional action. First, the facilitator asks the question “How does your back feel now?” to which Sam replies, “Hey, it feels a lot better.” Assuming that Sam is reporting what he actually feels (which may not always be the case, as sometimes people will tell you what they think you want to hear), this is a key piece to the puzzle of trauma treatment and is, in fact, inviting an act of interoception. Sam made a choice (to stand) and then he took an intentional action (standing on purpose) but when he notices that his back now feels better (interoception) it is at this point we can say that Sam has taken an effective action. So an effective action is not the action or intentional action itself but rather the action or the intentional action plus the experience of noticing that the action we have taken makes us feel better (notice that an action can end up being effective even if it wasn’t intentional: “I just stood up for some reason and then noticed how much better my back felt. I hadn’t even realized how sore my back was!”). We cannot determine whether or not an action is effective until we have taken it. In Sam’s case, to check out the effectiveness of his action even further, he decided to try it again and this time to notice the muscles he used to make it happen. He was able to identify and feel specific muscles that he used in order to stand and then, one last time, to acknowledge that his back felt better. In an attempt to characterize an internal process, I would suggest that what happened was Sam noticed he could feel muscles in his legs, which he could use to help him move from sitting to standing; as a result, by using his leg muscles on purpose, his back felt better. (This sounds a little simplistic but it is the kind of process we hope will become as conscious as possible to our clients. They may not connect all of the dots but even a couple would be very helpful in the overall process of trauma treatment.) Through this process of taking action, Sam began to solidify new truths within his organism that his body is feel-able, has agency, is effectual and capable of feeling more than one thing, and can do something on purpose to change the way he feels. This process, after all, is how a healthy organism functions.

Please note, however, that in the context of TSY, as I have stated before, it would have been an equally valid trauma treatment had Sam noticed that his back still felt the same or even worse after standing. It is not primarily the fact that Sam’s action was effective that made this process a useful part of treatment. It was the fact that Sam was able to interocept, make a choice, and take action. It is not required or expected that people feel better as a result of any of this: it is just one possibility among many. Taking action in TSY just allows for the possibility of perceiving change but it does not require any perceived change to be for the better. If, for example, Sam felt more pain in his back when standing it would be possible for him and the TSY facilitator to try other yoga forms like a gentle twist or a seated forward fold, for example (see Chapter 8 for these and other possibilities). Perhaps Sam would find that one of these forms relieved his back pain; if not, if the whole thing became overwhelming for that day, he could stop TSY altogether and move on to something else (like some kind of verbal processing if the TSY facilitator is a qualified clinician). The bottom line is that some clients will practice the motoric aspect of taking action, others will engage in the intentional aspect of taking action, and some will notice when an action is effective. With TSY we just want to make all of these possibilities available as often as possible and as long as they are tolerable to our clients.

Our experience working with people who have experienced complex trauma is that most often this process is disrupted at some point along the way: people may not feel the back tightness in the first place or, if they do, they may not have any idea what to do with it or, if they do have an idea and make a choice about what to do, they may not be able to carry out their choice. As we have seen, the reasons behind this disruption may be neurophysiological (less activity in the interoceptive pathways of the brain as a result of trauma) or relational (learning through experience with traumatic relationships that it is safer to not feel oneself or to not express vulnerability or to not trust one’s intuition to act) or something else but, for our purposes, the underlying reason doesn’t matter so much. The fact is that, in our work with trauma survivors, it is very common for people to experience one or more of these kinds of disruptions and that this is a large part of why it is so difficult to live with the impact of trauma: we can’t feel our bodies, we can’t make choices about what to do with our bodies, and/or we have difficulty taking action of any kind, especially actions based on what we feel in our bodies. With the example above, Sam may have begun rebuilding his frontal lobe or he may be learning through his relationship with the TSY facilitator that it is safe and acceptable to feel something, to express it to another person, and to make a choice about what to do and so on. As of the publication of this book, though we can speculate based on the evidence we have begun to accumulate, we just do not know the underlying mechanisms of TSY to a definitive empirical degree. But one thing is for sure: Sam is having experiences with his body that are different from experiences of trauma. He specifically feels his back, he chooses to do something about it, he acts on his choice, and, in this case, he notices a positive outcome.

Integrating interoception, making choices, and taking action

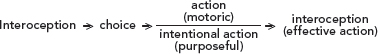

I consider some combination of interoception, choice making, and action taking to be at the heart of TSY. They do not have to happen all at once for a session to be considered successful, but we, as TSY facilitators, should always be oriented to ways we can bring them into the process. In my example above, I identified action (and especially intentional action) with choice, and effective action with interoception. Figure 4.1 represents a way to bring them all together.

Figure 4.1 begins with noticing what we feel in our bodies (introception), which leads to making a choice based on what we feel in our bodies, which is followed by acting either intentionally (purposefully) or not (purely motorically) and ends back with interoception, which determines whether or not the action was effective. This process represents a fundamental shift from a way of being whereby we are uncontrollably living in a body that belongs to the past (trauma) to living in a body that exists in the present and that can change from one state or experience to another. All of these components are the opposite of trauma in the way that I have defined it. Figure 4.1 gives a general way to understand the process but it is a linear model, which implies a rigid approach. Therefore, while it may be helpful in some circumstances to think linearly, let’s consider another model that opens up the possibilities, as depicted in Figure 4.2.

Figure 4.1. A linear depiction of integrating interoception, making choices, and taking actions

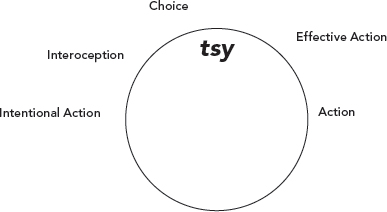

In Figure 4.2, the process is not linear but circular and can begin at any point marked on the circle. For example, an experience could begin with interoception, which may have been the case for Sam (noticing his back was sore), which leads to a choice (the idea to stand), which leads to an intentional action (standing on purpose), which then led to further interoception (noticing his back felt better), which allows Sam to understand the action as an effective one. It would also be possible for a cycle like this to begin with an action like standing up, then lead to interoception like noticing your knee hurts when you stand, which may lead to other choices and/or actions. The broad suggestion here is that as long as we are engaged in either interocepting, choosing, and acting either motorically or purposefully (or some combination of these dynamics), we are not stuck in a trauma paradigm. We experience new possibilities with regard to our bodies that are not the same as typical traumatic body experiences like not feeling, not knowing what to do, and not knowing how to make bad feelings change. Or, as Bessel van der Kolk has said, “Once patients become aware of their sensations and action tendencies they can set about . . . exploring new ways of engaging with potential sources of mastery” (van der Kolk, 2006, p. 13).

Figure 4.2. A circular depiction of integrating interoception, making choices, and taking actions

Once a client begins to develop some level of comfort and familiarity with interoception, choice, and taking action, then the two of you together may want to experiment with increasing the complexity and the depth of the experience. Yoga forms like those presented throughout this book offer myriad opportunities to feel what you feel, make choices, and take actions. The continued challenge for the TSY facilitator is not to turn these experiences into stories about the past (i.e., ways we acted or did not act previously) or the future (i.e., ways we might act in the future) but to keep the focus solely on what is happening right now. In the broader course of therapy there certainly may be time and space for talking about the past or the future but TSY is an opportunity to focus completely on having and noticing experiences that are happening in the here and now and to experiment with interacting with what you feel in your body by taking actions.

Conclusions

Like interoception and choice making, the practice of taking action is a key part of the TSY methodology. However, like everything else we have encountered, the kind of action we are going for is the self-motivated kind: the kind we choose for ourselves. Because of the context of complex trauma treatment there will be times when the facilitator will need to make the idea of an action available to a client but this is when it is critically important that they are committed to not commanding or coercing. Every idea, every cue, is presented as a genuine invitation for the client. The action becomes valuable only if it is self-motivated and/or based on interoception. If the action is taken as a result of external coercion, it is at best a waste of time and at worst retraumatizing. The encouragement is to proceed cautiously but to give as many opportunities as possible for your clients to use the yoga forms as ways to take self-motivated actions.

We have established interoception, choice making, and action taking as the foundational aspects of TSY methodology but there are some other vitally important qualities of the practice that we can look at throughout the next three chapters, beginning with an investigation of the present moment and how it bears on the treatment of complex trauma.