Paediatric elbow

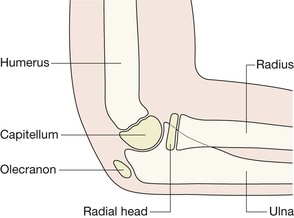

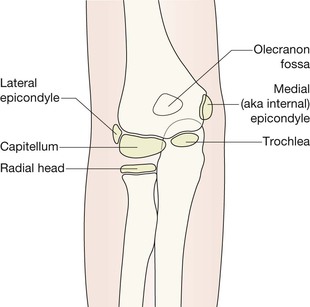

Anatomy

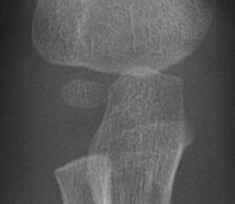

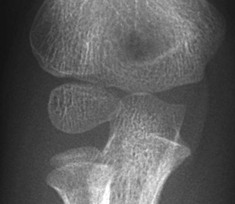

AP view—child age 9 or 10 years

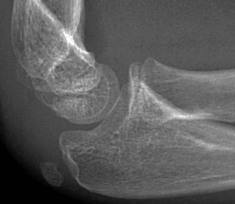

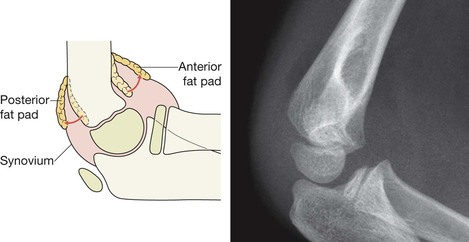

Elbow fat pads

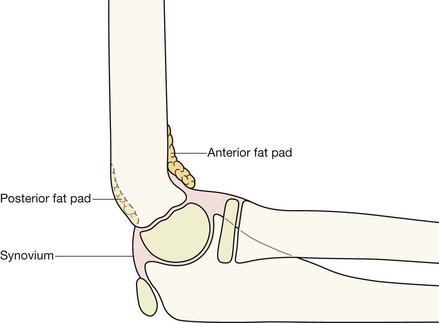

There are pads of fat close to the distal humerus, anteriorly and posteriorly. They are extrasynovial but intracapsular.

▪ Look for the fat pads on the lateral. They are not seen on the AP view.

▪ The fat is visualised as a dark streak amongst the surrounding grey soft tissues.

▪ The anterior fat pad is seen in most (but not all) normal elbows. It is closely applied to the humerus, as shown below.

▪ The posterior fat pad is not visible on a normal radiograph because it is situated deep within the olecranon fossa and hidden by the overlying bone.

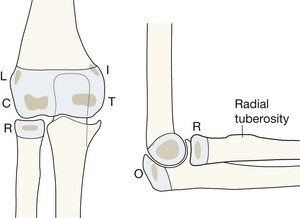

AP and lateral: the CRITOL sequence

CRITOL: the sequence in which the ossified centres appear

At birth the ends of the radius, ulna and humerus are lumps of cartilage, and not visible on a radiograph. The large, seemingly empty, cartilage filled gap between the distal humerus and the radius and the ulna is normal.

From 6 months to 12 years the cartilaginous secondary centres begin to ossify. There are six ossification centres. Four belong to the humerus, one to the radius, and one to the ulna. Gradually the humeral centres ossify, enlarge, and coalesce. Eventually each of the fully ossified epiphyses fuses to the shaft of its particular bone.

Exceptions to the CRITOL sequence?

Exceptions are an occasional normal variant3,4.

A 2011 survey4 of 500 paediatric elbow radiographs found:

▪ 97% followed the CRITOL order.

▪ 3% showed a slightly different order.

▪ But: there were no instances in which the trochlear ossification centre appeared before the medial (internal) epicondylar centre.

Conclusions

▪ CRITOL is a really helpful tool when analysing a child's injured elbow.

▪ Occasionally a minor variation in the sequence may occur.

▪ Use the rule: “I always appears before T”. So, if you see the ossified T before the I then the internal epicondyle has almost certainly been avulsed and is lying within the joint… ie it is masquerading as the trochlear ossification centre (see p. 105).

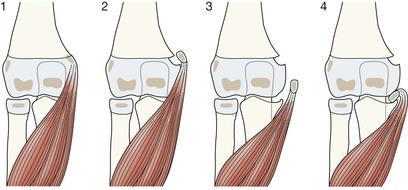

Medial epicondyle—normal anatomy

Is the medial epicondyle slightly displaced/avulsed? A common dilemma.

▪ The rule to apply:

On the AP radiograph a normally positioned epicondyle will be partly covered by some of the humeral metaphysis.

▪ A caveat:

Occasionally a child in pain will hold the forearm in a position of slight internal rotation. Rotation will project the metaphysis of the humerus away from a normally positioned epicondyle.

▪ Conclusions:

When checking the position of the internal epicondyle on the AP radiograph:

1. If part of the epicondyle is covered by part of the humeral metaphysis then an avulsion has not occurred.

2. A completely uncovered epicondyle indicates an avulsion… unless the forearm bones are slightly rotated.

Analysis: four questions to answer

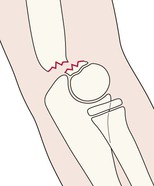

Question 1—Are the fat pads normal?

Check the fat pads on the lateral projection.

If an effusion is present it distends the capsule, displacing the fat pads away from the bone. This provides evidence of a significant injury.

▪ A displaced anterior fat pad (the sail sign) is abnormal8.

▪ A visible posterior fat pad is always abnormal1. It denotes a very large effusion—usually a considerable volume of blood in the joint.

▪ Not all joint effusions are associated with a fracture8.

▪ An effusion indicates that a significant injury has occurred, even if a fracture is not seen. Whenever either fat pad is displaced but no fracture identified, the arm needs to be placed in a collar and cuff until orthopaedic assessment a few days later. Some of these patients will have sustained an undisplaced fracture8,9.

▪ NB: Absence of a visible fat pad does not exclude a fracture. The radial neck is usually extracapsular, and a fracture of the neck may not produce a joint effusion/haemarthrosis or displace the fat pads. Alternatively, if the joint capsule has ruptured, blood gradually leaks out of the joint into the surrounding soft tissues.

Clinical impact guidelines: Fat pad displacement, but no fracture or dislocation identified — what to do?

It is most important that neither an undisplaced supracondylar fracture nor a displaced internal epicondyle are overlooked. The radiographs must be checked by an experienced observer before the patient is discharged.

If a fracture is still not identified then manage as for an undisplaced fracture. At clinical review in 10 days: if clinically normal—no further radiography; if clinically abnormal—obtain repeat radiographs.

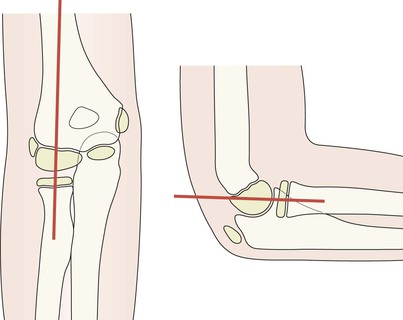

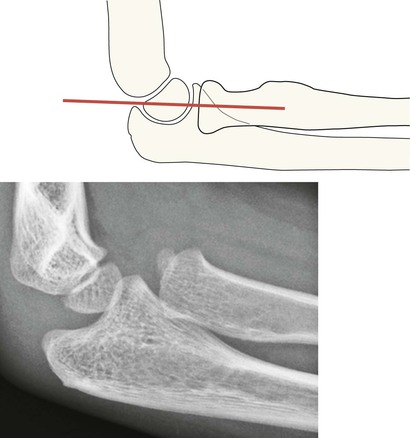

Question 2—Is the anterior humeral line normal?

The supracondylar region is a site of particular weakness in the developing humerus. There is a deep posterior fossa above the humeral condyles, which allows the olecranon to lie within it when the forearm is fully extended. Thus the humerus has a narrow AP diameter at this level and is a point of weakness.

The rule: A line traced along the anterior cortex of the humerus should have at least one third of the capitellum anterior to it (see p. 101).

▪ If less than one third of the capitellum lies anterior to this line, there is a strong probability of a supracondylar fracture with the distal fragment (including the capitellum) displaced posteriorly (see p. 107).

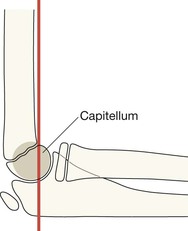

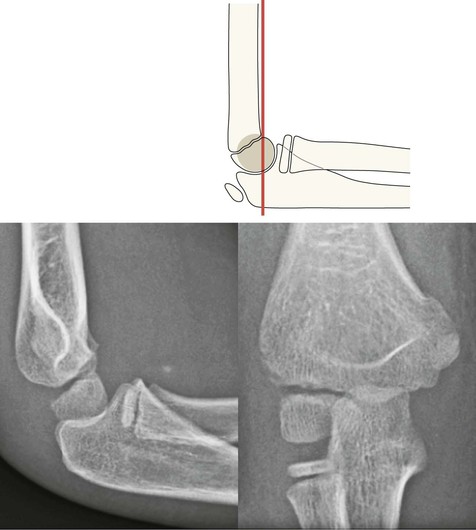

Question 3—Is the radiocapitellar (RC) line normal?

The rule: A line drawn along the longitudinal axis of the radial head and neck should pass through the capitellum. If it does not pass through the capitellum: a radial head dislocation is likely.

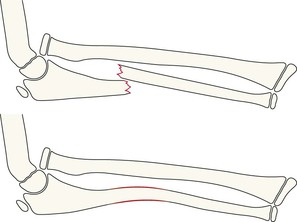

▪ Be careful: the normal radius frequently shows a bend or slight angulation in the region of its tuberosity. Draw the RC line along the long axis of the proximal 2–3 cm of the radius…not along the long central axis of the shaft of the radius.

▪ Be careful: this rule is always valid on a true lateral7, but on the AP radiograph the RC line can be distorted by radiographic positioning. A misleading RC line on the AP view may also be due to eccentric ossification of either the radial head or the capitellar epiphysis, which can cause the RC line to be directed away from the capitellum.

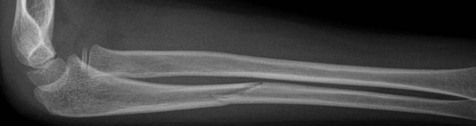

▪ Be very careful: Monteggia injury1,2. Whenever there is a fracture of the shaft of the ulna, evaluate the RC line carefully, because there may be an associated dislocation of the radial head. Particularly likely when there is angulation or displacement of the fracture but the radial shaft appears intact (see pp. 112–113).

The common injuries

Supracondylar fracture

60% of elbow fractures9–12. The commonest fracture in children under the age of 7 years, and the second commonest up to the age of 16 years9.

Caused by falling on an outstretched hand with hyperextension of the elbow. The supracondylar bone is relatively thin and weak in a child.

25% of these fractures are minimally displaced or undisplaced11,12. Displacement is usually posterior due to the direction of the fall. Very occasionally the displacement is anterior, resulting from a blow to the posterior aspect of the elbow.

Assessment of the anterior humeral line (p. 101) is the key to recognising any posterior displacement of this fracture.

Clinical impact guideline:

This fracture may cause vascular damage if there is major displacement. The brachial artery is situated anterior to the humeral cortex in the supracondylar region of the humerus, and can be lacerated by a bone fragment.

▪ If this fracture is displaced it needs to be reduced and stabilised to protect the vascular supply to the arm12.

▪ Bleeding from torn vessels can also cause a compartment syndrome; ie bleeding or swelling within the adjacent muscles that are enclosed by a tight fascia. The pressure within the compartment can rise and this can cut off the blood supply to the muscles.

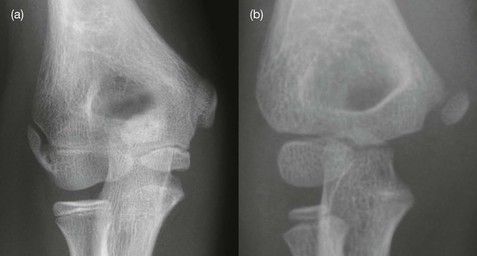

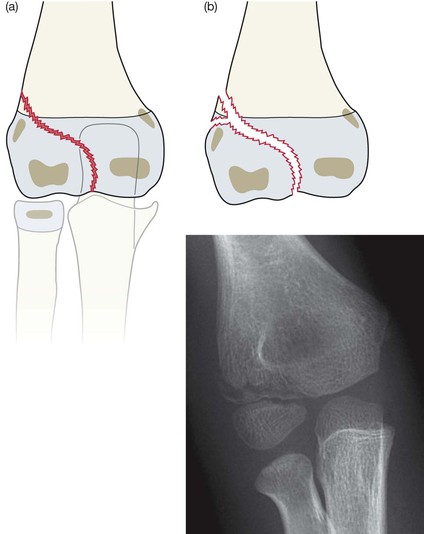

Fracture of the lateral humeral condyle

The commonest fracture in children under the age of seven years. In many cases the fracture involves only the cartilaginous part of the distal humeral epiphysis. Cartilage does not show up on a radiograph. Consequently, the extensive epiphyseal component of this fracture is often not fully appreciated. In effect this is a Salter–Harris type 4 epiphyseal fracture (see p. 15).

▪ Precise reduction is important If the fracture is displaced. Otherwise stiffness, cubitus valgus and / or a delayed ulnar nerve palsy may result13.

▪ Helpful hint: there is a recognised association between olecranon fractures and lateral condyle fractures. Have you checked the olecranon?

Avulsion of the medial epicondyle

Results from a pull at the insertion of the common origins of the flexor muscles, usually as a result of a valgus stress during a fall on the outstretched hand. May also occur in throwing sports such as baseball pitching (“little leaguer's elbow”).

Minor avulsion is common. The avulsed ossification centre will usually heal by fibrous union and the attachment of the flexor muscles will be stable5,6,13. Surgical reduction is often indicated when the avulsion is extensive, in order to obtain and preserve full function.

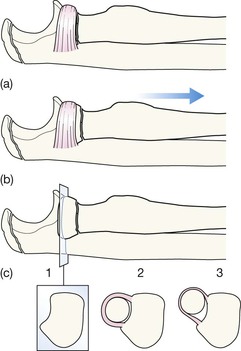

Pulled (“nursemaids”) elbow

Usually occurs between the age of one and four years.

Caused by a sudden jerk on the arm, often when restraining a child who is charging off to cross a busy road, or when being playfully swung around by the arm. The jerk causes the annular ligament around the head of the radius to stretch and consequently the radial head subluxes or slips very slightly.

Clinical findings are classical: the arm is held in flexion and pronation. Reduction is usually simple, quick and effective.

Radiography is not indicated as the history and clinical findings are characteristic. Also, the radiographs will always appear normal.

Rare but important injuries

Avulsion of the lateral epicondyle

A very rare injury. The normal elbow will often show the lateral epicondyle well away from the adjacent humeral metaphysis. This is not a cause for worry if the two adjacent cortices parallel one another (as shown on p. 113).

Monteggia injury

A Monteggia injury adheres to the principle of the Two Bone Rule. In a two bone system15 such as the radius and ulna, where the bones are tightly bound together, they can be regarded as acting as a single functional unit. If one of the bones is fractured and displaced (or bent in a child) then there will need to be an additional disturbance in their relationship, often a displaced fracture of the adjacent bone. If the adjacent bone is intact then the disturbance will affect a joint. A Monteggia injury comprises a displaced fracture of the ulna (or a bowed ulna), an intact radial shaft, and a dislocated head of the radius.

Pitfalls

Normal variants that can mislead

Puzzled by the appearance of the epicondyles?

▪ On the lateral projection do not be alarmed at seeing the medial epicondyle situated very far posteriorly (p. 108). This is its normal position.

▪ The external (ie lateral) epicondyle can be normal but seemingly widely separate from the humerus. The rule to apply: when normal, its lateral border is always parallel to the cortex of the adjacent humeral metaphysis (p. 112).