Particular paediatric points

Bones in children are different1–4

“A child is not a small adult …”

This truism is particularly important in relation to paediatric bone injuries1

Child versus adult

There are three major differences between a child's and an adult's skeleton2–4.

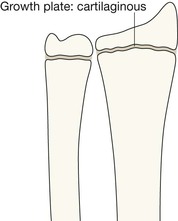

1. Children have growth plates that:

□ have the consistency of hard rubber and act, in part, as shock absorbers

□ protect the joint surface from sustaining a comminuted fracture

□ are weaker than the ligaments. Consequently the epiphysis will separate before a dislocation (ie ligamentous disruption) occurs.

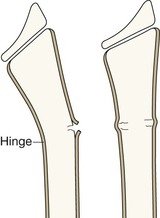

2. Children have a thick periosteum that:

□ is not only thick but very, very, strong

□ acts as a hinge, which inhibits displacement when a fracture occurs.

3. Children's bones have an inherently different structure to adults' bones, being:

□ flexible, elastic, and plastic, allowing an injured bone to bend or to buckle.

The end of a long bone in a child

You need to be familiar with the normal radiographic appearance of the ends of the long bones in children. This will help you to detect the important injuries and will also protect you from labelling a normal developmental appearance as being abnormal.

A persistent lucent line is normal

A child's long bone grows in length initially by forming layers of cartilage and gradually converting that cartilage into bone. This layering process takes place at the end of the bone at the site of the physis (also called the epiphyseal plate or the growth plate). The physis is made of cartilage and lies between the epiphysis and the diaphysis. Cartilage is lucent on a radiograph. The cartilaginous physis remains as a radiographic lucency until the child reaches skeletal maturity and stops growing. At that time the lucent physis fuses to the metaphysis (and also to the epiphysis). When fusion occurs the linear lucency that was the physis disappears.

Parts of the skeleton are not missing

An epiphysis is a secondary centre of ossification at the end of a long bone. Each epiphysis is initially composed solely of cartilage. As a consequence it looks as though nothing is there (take a look at a new born baby's elbow region). Of course each of the epiphyses is present, but present as a radiolucent blob of cartilage. These invisible blobs enlarge slowly with age. Eventually they begin to ossify at their centres and become visible. Finally, these blobs of bone will fuse to the physis at maturity.

Fracture sites1,3

“The key to accurate diagnosis is a precisely accurate assessment of the radiographs.”2

Epiphyseal–metaphyseal (Salter–Harris) fractures

The growth plate (the physis) is a very vulnerable structure. The joint capsule, the surrounding ligaments and the muscle tendons are all much stronger than the cartilaginous physis.

A shearing or avulsion force applied to a joint is most likely to result in an injury at the weakest point, ie a fracture through the growth plate.

Most growth plate injuries will heal well without any resultant deformity. However, in a few patients, failure to recognise a growth plate injury may result in suboptimal treatment with a risk of premature fusion resulting in limb shortening. If only a part of the growth plate is injured, unequal growth may lead to deformity and disability.

The Salter–Harris classification

This classification links the radiographic appearance of the fracture to the clinical importance of the fracture. A Salter–Harris type 1 injury has a good prognosis whereas a Salter–Harris type 5 injury has a poor prognosis.

How to remember the Salter–Harris (SH) classification

| SH 1 | = S | is Separated (a widened physis) |

| SH 2 | = A | is Above the growth plate |

| SH 3 | = L | is beLow the growth plate |

| SH 4 | = T | is Through the growth plate |

| = E | is for nothing! | |

| SH 5 | = R | has a Rammed together growth plate |

Metaphyseal–diaphyseal fractures

When a child's long bone is subjected to a longitudinal compression force (such as a fall on an outstretched hand), this can result in two common but different types of injury in the region of the metaphysis and proximal diaphysis.

Toddler's fracture8–10

The classic toddler's fracture involves the shaft of the tibia. Usually it occurs in a child aged 9 months to 3 years. The child falls with one leg fixed and a twisting injury occurs resulting in a spiral fracture of the tibia.

Invariably, the fracture is undisplaced and is frequently very difficult to visualise on the initial radiographs. Sometimes it will only be demonstrated on an additional oblique projection, or on a radionuclide study. If a repeat radiograph is obtained 10–14 days after the injury periosteal new bone will be present.

Sports injuries14–17

Sports injuries affecting young children and adolescents are common. Some of these patients will attend the Emergency Department complaining of acute or chronic pain.

Acute Injuries

Acute fractures follow the same patterns as those that occur as a result of accidental trauma in the playground or elsewhere. Salter–Harris growth plate fractures, Torus and Greenstick fractures, and plastic bowing fractures are described on pp. 14–21.

Chronic injuries

A chronic sports injury may cause diagnostic difficulty to the unwary. Three skeletal injuries occur: stress fractures, avulsion fractures, and osteochondral injuries.

Stress fractures15–20

Most stress fractures occur in the lower limbs as a consequence of weight bearing stresses in runners and footballers. Other activities can affect the ribs and upper limbs. The appearances of stress fractures on plain radiographs do vary.

Scintigraphy will detect a stress fracture when the plain radiographs appear normal.

MRI is the most sensitive test for identifying fractures in their very earliest stages19. If there is clinical suspicion of a stress fracture and the plain radiographs appear normal then MRI is the imaging test of choice; it will provide the maximum detail in relation to the fracture.

| Bone | Site | Recognised activities |

| Pelvis | Pubic ramus | Distance runners, gymnasts |

| Femur | Shaft/neck | Dancers |

| Tibia | Proximal third or junction of mid & dist thirds | Runners, footballers, dancers |

| Fibula | Distal third | Runners, footballers |

| Navicular | Centre | Runners, jumpers, footballers |

| Calcaneum | Jumpers | |

| Metatarsals | Shafts | Dancers, runners, footballers |

| Sesamoids | Runners | |

| Wrist | Growth plate | Gymnasts |

| Vertebrae L4 or L5 | Pars interarticularis | Dancers, fast bowlers, gymnasts, tennis players, USA football linemen |

| Ribs | First rib | Throwers |

Note: Stress fractures are not limited to these sites nor these activities only.

Radiographic appearances of stress fractures

| Early | Normal |

| 2-4 weeks | Variable findings: |

| Later | Callus and endosteal reaction |

If not recognised or treated, a stress fractures will sometimes progress to a complete and displaced fracture.

Avulsion injuries15,16,21,22

Apophyseal fractures occur almost exclusively in athletic children and adolescents21,22. Hurdling, sprinting, soccer, and tennis are the principal at-risk activities.

An apophysis is a secondary ossification centre that is not related to a joint surface. Consequently, an apophyseal fracture is a growth plate injury and is analogous to a Salter–Harris type 1 fracture. Apophyses are often the sites of tendonous insertions and avulsion occurs as a result of a violent or repetitive muscle pull. The most common avulsion sites are:

▪ Anterior inferior iliac spine (AIIS)

▪ Anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS)

▪ Humerus: medial epicondyle. (Incidentally this is not an apophysis. It is an epiphysis.) Nevertheless, avulsion is fairly common at the elbow. It represents the so-called “little leaguer's elbow” because throwing sports can cause the medial epicondyle to be pulled off. These activities include baseball pitching.

For additional detail about avulsion injuries at particular sites see:

Chondral & osteochondral injuries14,15

Repetitive trauma with impaction of one cartilage covered bone on another can cause fissuring within the underlying bone. A defect may result and a lucency within the affected bone can become visible on the radiograph. The lesion is termed osteochondritis dissecans (OCD). Sometimes a bone fragment becomes loose and may be seen within the joint. The sites most commonly affected are the:

Chest emergencies23–26

Children attend the Emergency Department with upper and lower airway problems including coughing, chest trauma, wheezing, and pneumonia. The plain film radiology of these problems is addressed in The Chest X-Ray: A Survival Guide24.

For swallowed foreign bodies, see pp. 349–362.

Inhaled foreign body

Infants and toddlers are at risk of foreign body aspiration, frequently unwitnessed. The most commonly inhaled foreign body is food, often a peanut23,25,27–30. A history of choking is usually obtained. Common clinical signs include coughing, stridor, wheezing and sternal retraction. Rapid recognition and treatment are essential.

Radiography

If the child is able to cooperate then a frontal chest X-ray (CXR) should be obtained following a rapid forced expiration. Air trapping on the affected side (due to obstruction of the airway) is then more obvious.

Fluoroscopy is an excellent way of observing whether there is unilateral air trapping.

Possible findings on the CXR:

▪ Obstructive atelectasis—areas of collapse/consolidation.

▪ Obstructive emphysema—a unilateral hypertransradiant lung, due to air trapping. The affected lung appears blacker and larger than the opposite normal side.

▪ Normal appearances. This is not necessarily reassuring. If the clinical suspicion remains that a foreign body has been inhaled then an emergency MRI28 or bronchoscopy is essential.

Child abuse: skeletal injuries31–34

The possibility of non-accidental injury (NAI) must be considered in all injured children presenting to the Emergency Department. No socioeconomic group or race is exempt.

Normal radiographs do not exclude the diagnosis. In 50% of proven cases of NAI the radiographs are normal. Nevertheless, fractures are the second most common finding in child abuse; second, after cutaneous abnormalities such as bruises and contusions.

Under- and over-diagnosis of NAI31,34

Failure to diagnose a particular injury as being suggestive of abuse in a child attending the Emergency Department can have devastating consequences. Similarly, an over-diagnosis of NAI can be highly detrimental for the child and for those who are looking after the child. A particular area of difficulty is the evaluation of an infant's or toddler's skull radiographs because of the skull sutures (see pp. 36–45).

Radiological pitfalls in the diagnosis of NAI in the Emergency Department

1. Failure to consider the possibility of child abuse.

2. Ignorance of the particular or specific radiological features (ie appearance or position) that should raise the suspicion of NAI.

3. Normal skeletal variants misinterpreted as evidence of NAI. These include accessory skull sutures, physiological periosteal reaction, and normal metaphyseal variants35.

5. Other pathological processes, such as osteogenesis imperfecta, osteomyelitis and scurvy may simulate some of the skeletal features of NAI.