Chest

Normal anatomy

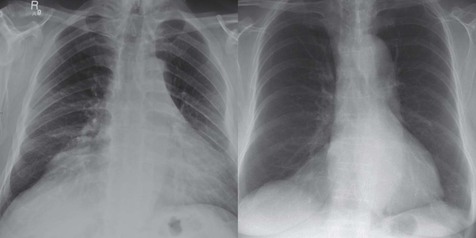

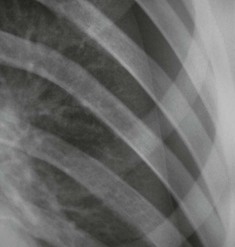

Frontal CXR—the lungs

Frontal CXR—lung markings

Normal lung markings are solely due to vessels and to nothing else. The normal bronchial walls, normal interstitium, and normal lymphatics are not visible.

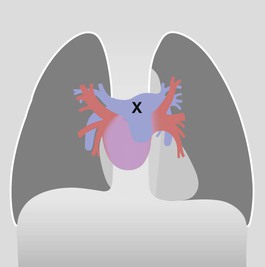

Frontal CXR—hila

The hilum is the site at which the bronchi and vessels enter or leave the lung.

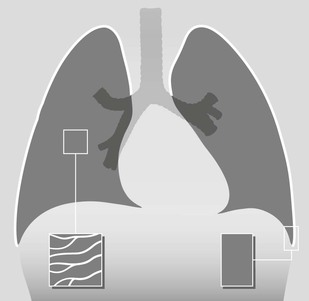

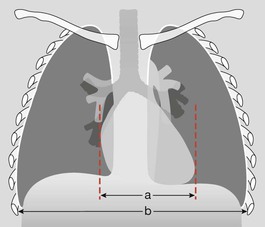

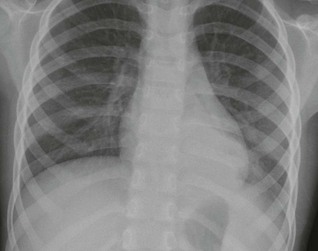

Frontal CXR—cardiothoracic ratio

Most normal hearts have a cardiothoracic ratio (CTR) of less than 50% when assessed on a PA chest radiograph obtained in full inspiration2.

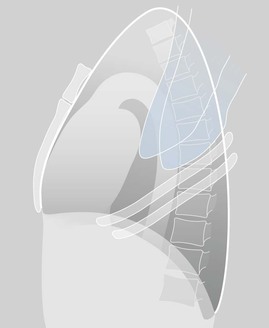

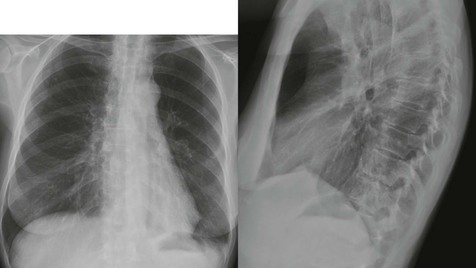

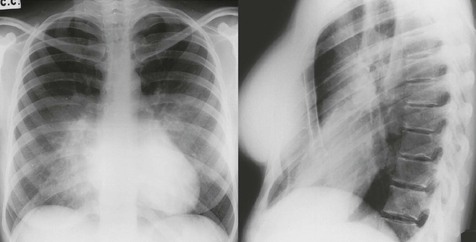

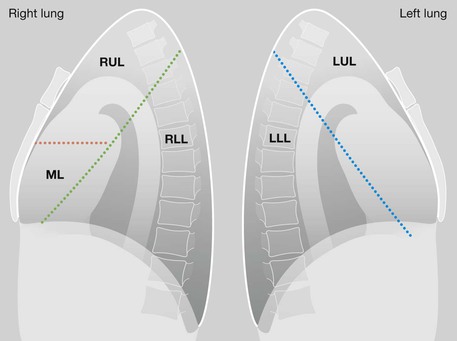

Lateral CXR—the lobes of the lung

The two fissures in the right lung divide the lung into three lobes.

The single fissure in the left lung divides the lung into two lobes.

The oblique fissure on each side is propeller shaped and consequently we only, and very occasionally, see a part of a fissure on a normal lateral CXR.

On the other hand, we will see most of the horizontal fissure on the lateral CXR because it is straight. We will often see this fissure on the frontal CXR for the same reason.

Analysis: the checklists

The frontal CXR

Four steps underpin accurate analysis.

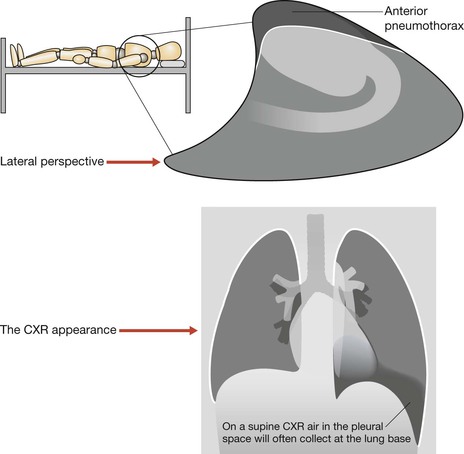

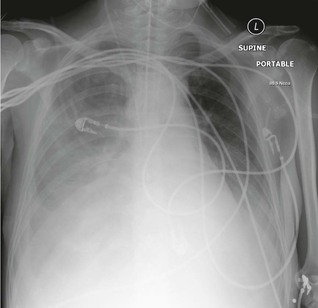

1. Check whether the CXR is a PA or an AP radiograph and whether it was obtained erect or supine. An AP CXR will magnify the heart shadow; a supine CXR will alter the position of pleural air or pleural fluid.

2. Check whether there is an adequate inspiration. A small inspiration alters the normal appearance of the heart and lung bases.

3. Direct your initial analysis to your primary clinical concern. Is your primary concern: a left sided pneumothorax? A right sided pleural effusion? A coin lodged in the oesophagus?

4. Now you can assess the radiograph in an organised and systematic manner. As follows:

□ Is the heart enlarged?

In an adult, the cardiothoracic ratio (CTR) should be < 50% on a PA CXR (see p. 309).

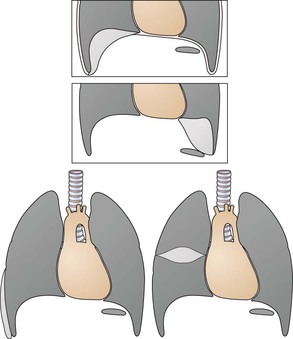

□ Are both domes of the diaphragm clearly seen and well defined?

If part of a dome is obscured, suspect pathology in the adjacent lower lobe.

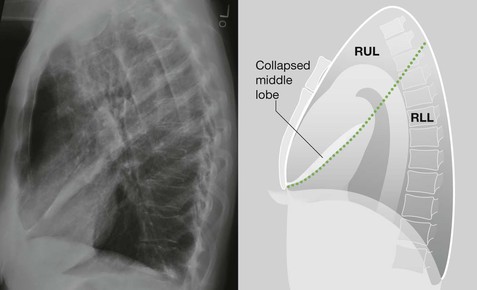

□ Are both heart borders clearly seen and well defined?

If not, there is a high probability of pathology in the immediately adjacent lung.

□ Are the hila normal … position, size, density?

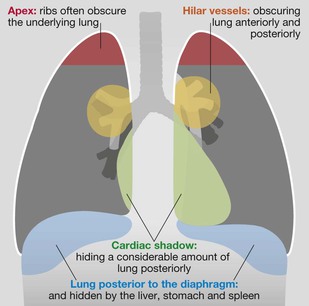

□ Check the tricky hidden areas of the lung: both apices, behind the heart shadow, around each hilum, below the diaphragm (see p. 308).

□ Finally, ask yourself once again:

Have I addressed this patient's particular clinical problem?

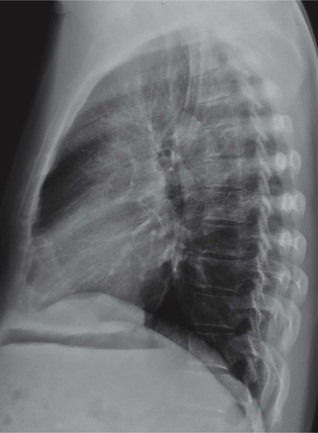

The lateral CXR

Four questions underpin accurate analysis:

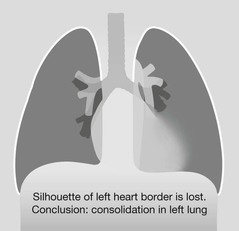

1. Are the vertebral bodies becoming blacker from above downwards?

If not (ie they are becoming whiter or greyer) then suspect disease in a lower lobe or in a pleural space.

2. Are the domes of the diaphragm clearly visualised? Remember that one dome, the left dome, disappears anteriorly because the heart is tight up against it. If any other part of either dome is obscured—suspect consolidation or collapse in the adjacent lung.

3. Is there any abrupt change in density across the heart shadow?

“An abrupt change in density” is likely to be a lung abnormality.

4. Have I correlated my findings on the lateral CXR with the frontal CXR appearances?

Ten clinical problems

The full breadth of the radiology of thoracic disease as revealed by the plain CXR is addressed in our companion book The CXR: A Survival Guide1. We cannot cover that detail in this single chapter.

Instead, we will consider the ten clinical problems that account for well over 90% of all CXR requests made in the Emergency Department. We will take each problem in turn and pose a clinical question of the frontal CXR.

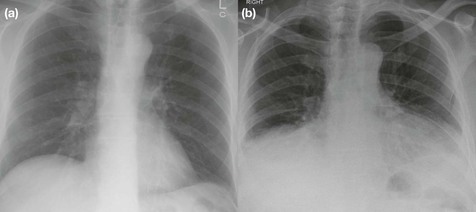

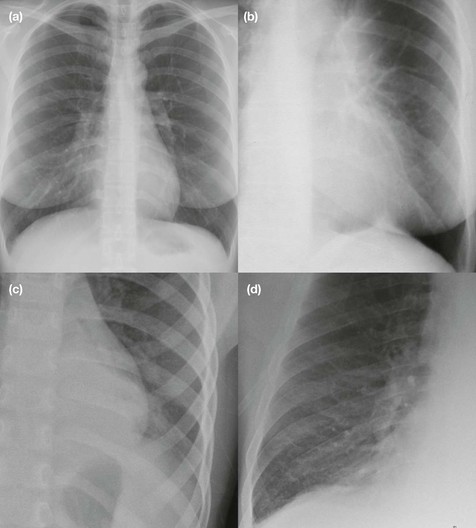

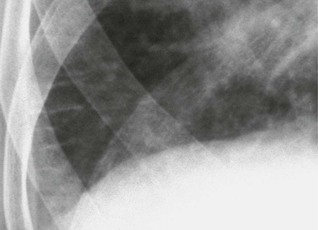

Question 1: Is there pneumonia (consolidation)?

Physical examination is not always sufficiently accurate on its own to confirm or exclude the diagnosis of pneumonia3. Many pneumonias will be obvious on the frontal CXR. Some are much more difficult to detect—the hidden pneumonias.

Detecting a hidden pneumonia

▪ Search for any evidence of a silhouette sign1,2,4 on the CXR.

▪ Assess the mediastinal and diaphragmatic boundaries/borders.

▪ When a border is ill-defined, the precise site of a concealed area of consolidation is revealed. Sometimes the loss of a border is much more obvious than the actual air space density that occurs with a pneumonia.

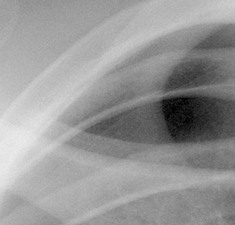

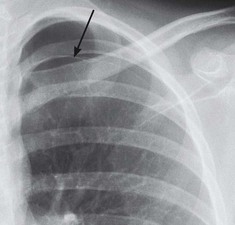

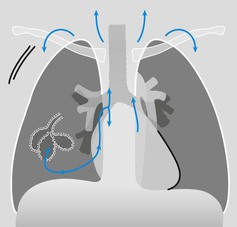

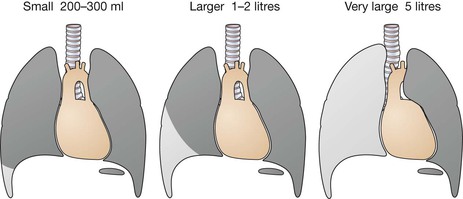

Question 2: Is there a pneumothorax?

An erect CXR obtained in full expiration is recommended. The normal lungs are more opaque (or slightly whiter) on an expiration CXR. Consequently, when a pneumothorax is present the air (black) in the pleural space contrasts with the adjacent (whiter) lung. This accentuation of the difference in contrast, as compared with an inspiration film, sometimes makes it slightly easier to detect a pneumothorax.

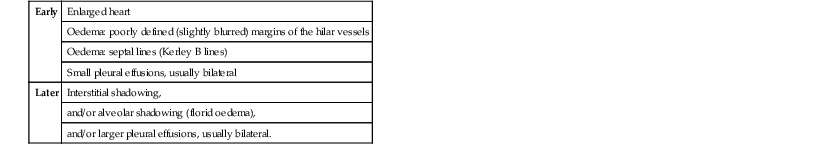

Question 3: Are there signs of left ventricular failure (LVF)?

Look for cardiac enlargement and for lung and pleural changes.

Question 4: Severe asthmatic attack—is there a complication?

The complications to look for are lung consolidation, lobar collapse, pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum.

Question 6:

When assessing the mediastinum there are no absolute measurements that indicate abnormal widening on a frontal CXR.

Aortic dissection4,6,7

▪ In the appropriate clinical setting mediastinal widening, with or without a left pleural effusion, is highly suggestive.

▪ Always compare the present CXR with any previous CXR, if available. An alteration to the mediastinum may be obvious.

▪ Clinical suspicion of a dissection must take priority over a normal CXR, and additional imaging becomes mandatory in all cases.

Traumatic rupture8–10

▪ 30% of patients with an aortic rupture have a normal CXR on presentation. If the CXR is normal, the level of clinical concern will determine whether an additional definitive radiographic examination (for example CT) is needed.

▪ A widened mediastinum does not necessarily indicate aortic rupture following blunt trauma to the chest. Tearing of small mediastinal veins is the most common cause of mediastinal widening on the CXR.

Question 7: Is there a rib fracture?

Oblique views of the ribs are not indicated following a relatively minor injury to the thorax. Clinical management is rarely altered by demonstration of a simple rib fracture. A frontal CXR is obtained solely to exclude an important complication such as a pneumothorax.

Question 9: Is there evidence of a pulmonary embolus?1,4

90% of emboli occur without pulmonary infarction and the CXR often appears normal.

Sometimes non-specific CXR findings are present, including: small areas of linear collapse; a small pleural effusion; slight elevation of a dome of the diaphragm.

Whenever a pulmonary embolus remains a clinical possibility then—whatever the CXR findings—the patient requires definitive imaging, usually a CT pulmonary angiogram.