Today some museum curators still keep archaeological material that they consider ‘indecent’ or inappropriate for public display under lock and key. Several important collections of Roman ‘brothel tokens’, small coinlike objects that depict the sexual service that has been paid for, currently lie, unpublished, in European museum basements. They convey more information than the simple existence of the different services in ancient times. At first glance, it might be hard to see why fellatio should be cheaper than vaginal intercourse from the rear, but a coin specialist from Warsaw has recently conducted a blind test on present-day prostitutes. He asked them what they charged for different positions and acts. Their scale corresponded precisely with the Roman scale. For prostitutes with many clients, one of the greatest hazards is vaginal soreness — hence deeply penetrating positions, such as sex from behind, are more painful and therefore cost more .… These tokens crossed language barriers, and prostitutes could see just what a man had paid for (1).

In 1819, the future king of Naples, Francis I, visited the Naples museum with his daughter to see the collections from Pompeii. He suggested to the curator that it would be better to restrict those items which dealt with erotic subjects to a single room, so that access could be limited to ‘persons of mature age and of proven morality’. So 102 objects were isolated which might cause offence to the prevailing moral sentiments of the times, setting up the ‘Gabinetto degli oggetti osceni’. In 1823, the name was changed to ‘Gabinetto degli oggetti riservati’, a euphemism. These works could only be shown to people who had a valid royal permit. In 1849, the doors were closed to everyone, after other nude sculptures and paintings had been added. Three years later, the entire collection was transferred to a remote corner of the museum, as if to remove all trace of it. In 1860, Dumas père was made curator by Garibaldi, and he checked and catalogued the collection, renaming it ‘Raccolta Pornografica’, the same name it has today. More works were gradually put on show, and permission to see the special collection was granted to those who applied for a permit. Casual curiosity was thus discouraged.

1

The Roos Carr images are five small wooden human figures, dating to 2500 years ago, which were found in 1836 near the River Humber, in northern England. It has recently been found that what the Victorians took to be (and fitted as) detachable stubby arms are actually downward-curving penises!

For many years, unfounded reports circulated in whispers concerning the ‘depraved habits’ of the Incas and especially of the protagonists of the Moche culture — for example Posnansky, in 1925, referred to ‘horrifying sexual pottery’. The fact that, years ago, museums did not show the ‘erotic’ pots led to legends such as ‘homosexuality was then quite prevalent’ — whereas in fact there are very few clear examples of it: there is one known depiction of homosexual anal intercourse surviving. However, early this century, a scholar mentioned the presence of ceramics with ‘scenes of sodomy or pederasty’, adding that ‘a misunderstood modesty has led many collectors to destroy them’. No lesbianism is ever depicted. The sixteenth-century Spaniards were outraged by the widespread homosexuality and transvestism they found among the indigenous American peoples, and are thought to have systematically destroyed sculptures, jewellery and monuments that depicted and celebrated such practices.

Some nineteenth-century copies of rock paintings in Southern Africa deliberately omitted details such as urination or ejaculation coming from men and animals, and apparent infibulations.

Lots of primitive art in Java — some of it very phallic, from ancestor fertility cults — is hidden away in the back of museums. Even in this century, little loin cloths or skirts were put on them in Djakarta’s museums to spare the blushes of visitors — an ambassador’s wife had complained!(2) One item, now in purdah in a cupboard in Djakarta museum, and not on display, is a fifteenth-century, 2m-high stone phallus with an inscription, from Candi Sukuh on Mt Lawu; the main shrine was surmounted by it. The upper part of the shaft is decorated with four spheres — possibly connected to the South-East Asian custom whereby little balls were inserted under the skin of the penis.

2

There is a Greek example of an illustration of a phallic statue on a potsherd from Cyrene. The published photo has the phallus blacked out (though it is clear on the actual potsherd). The excavator’s wife insisted that the black pen be applied — she appears on a colour plate in the volume, planting flowers among the tombs!

Discovered during an era of sexual repression, ‘pornographic’ Greek vase paintings were, in many cases, locked away in secret museum cabinets — in Naples, Tarquinia, Munich, Boston, etc. As for ancient Egypt, a small fragment of a leather hanging from 1500 BC shows a girl playing the harp, while a naked man with a huge phallus turned backwards dances to the music — his left hand holds what seems to be a whip with several lashes. At the beginning of our century, the phallus was erased, and only an old photograph now shows it.

Indeed, whenever erotic drawings and figurines survived from Egypt, they frequently ended up in private collections or in inaccessible drawers in museums; and love and sex in the ancient Egyptian world are still known to only a few, because most of the texts were translated in the early twentieth century, when Victorian prudery was only just beginning to recede. Many of the Egyptian tomb reliefs and mythological stories were considered too shocking to publish. For example, an Egyptian creation legend describes how the god of creation, the sun god Atum, created himself from primordial matter. Then he was masturbated by the ‘divine hand’ and his seed formed the next two deities .… though in one papyrus a variant shows the god using his mouth instead of his hand. In the ancient daily rites for the god Atum at Karnak, the priestess of the temple reenacted this creation ritual with a large ithyphallic statue of Atum.

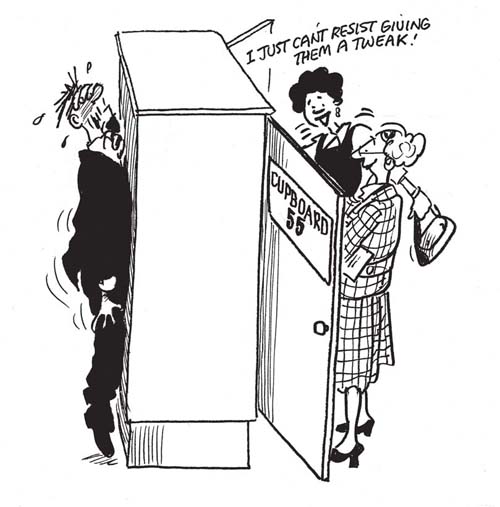

The Medieval and Later Antiquities section of the British Museum has a ‘Museum Secretum’, a locked cabinet, Cupboard 55, containing the collection of antiquities and objects of worship assembled by Dr George Witt, a surgeon who made his fortune in Australia as a banker, and who was also a former mayor of Bedford, where he was famous for his Sunday morning lectures on this collection of phallic antiquities.

It is thought that he was at the centre of an international circle of wealthy gentlemen who collected erotica. He probably showed off the objects to male friends after dinner parties. One object is called ‘St Cosmo’s big toe’, from 18th-century southern Italy, where it is thought to have been a popular sex toy (3). There is also a gentleman’s tobacco box, decorated on the outside with normal country scenes, but beneath the lid is a very graphic depiction of a couple ‘in flagrante delicto’, who are leaning against a horse which looks somewhat startled. He presented it to the Museum in 1865 ‘with the hope that some small room may be appointed for its reception’, but the Victorians believed that this material — representations of the phallus from across the centuries and the continents — should not be exposed to the female sex and young people, and placed it under lock and key. The museum’s Victorian curators described the contents as ‘abominable monuments to human licentiousness’, and they banned anyone except those of ‘mature years and sound morals’ from seeing them, and it is said that they may even have added to the collection themselves by breaking off the ‘corrupting’ parts of classical nude statues on display in the museum! Ironically, of those who today apply to have the cupboard unlocked, 90 percent are women (4). There are Assyrian erect penises, Egyptian ones, Greek and Roman ones, medieval ones, phalluses with wings, with eyes, with hawks’ heads, lead ones, phalluses in the form of signet rings, lamps, brooches .… Most were probably just symbols of good luck rather than anything overtly sexual.

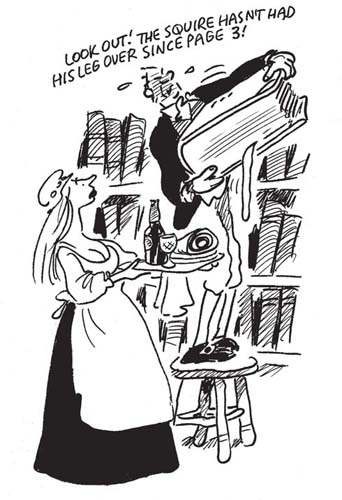

3

4

The collection also contains a steel chastity belt — no such thing dating from the Middle Ages has ever been found, anywhere in the world, but the Victorians believed in them, so this is almost certainly a Victorian fabrication. In 1953, the British Library found some late eighteenth-century condoms which had been used as bookmarks in a 1783 Guide to Health, Beauty, Riches and Honour; they were made of sheep intestines with delicate pink drawstrings, and they too were deposited in Cupboard 55 (5). This gives the lie to the old claim that it was the first Europeans in Australia who used sheep bladders as condoms, and the British who introduced the refinement of removing the bladders from the sheep first!

5

Aesop’s Fables, written 2600 years ago, far from being children’s stories, were in fact coarse, violent and cruel. The Victorians translated them from the ancient Greek, but suppressed 100 of them, which have only recently appeared in English for the first time. The translators, Robert and Olivia Temple, say that ‘the fables are not the pretty purveyors of Victorian morals that we have been led to believe. They are instead savage, coarse, brutal, lacking in all mercy or compassion. Some of them were probably suppressed because they were very violent and didn’t suit the purposes of the Victorians. They were brutal or they were non-Christian. They were about alien gods; they contained coarse, peasant humour and were very rude.’ Even some of the 250 or so that were already published had been mistranslated to give them a more comforting and more moral tone.

One example of an untranslated fable is about the beaver:

A beaver’s genitals serve, it is said, to cure certain ailments. So when the beaver is spotted and pursued to be mutilated — since he knows why he is being hunted — he will run for a certain distance, and he will use the speed of his feet to remain intact. But when he sees himself about to be caught, he will bite off his own parts, throw them, and thus save his own life. The moral: is that wise men will, if attacked for their money, sacrifice it rather than lose their lives.

One, entitled ‘The camel who shat in the river’, goes as follows:

A camel was crossing a swiftly flowing river. He shat and immediately saw his own dung floating in front of him, carried by the rapidity of the current. ‘What is that there?’ he asked himself. ‘That which was behind me I now see pass in front of me.’ The moral: This applies to a situation where the rabble and the idiots hold sway, rather than the eminent and the sensible (6).

The asses appealing to Zeus:

One day, the asses tired of suffering and carrying heavy burdens and they sent some representatives to Zeus, asking him to put a limit on their workload. Wanting to show them that this was impossible, Zeus told them that they would be delivered from their misery only when they could make a river from their piss. The asses took this reply seriously and, from that day until now, whenever they see ass piss anywhere they stop in their tracks to piss too. The moral: This fable shows that one can do nothing to change one’s destiny.

6

The Hyenas:

They say that hyenas change their sex each year and become males and females alternately. Now, one day a male hyena attempted an unnatural sex act with a female hyena. The female responded ‘If you do that, friend, remember that what you do to me will soon be done to you.’ The moral: This is what one could say to the judge concerning his successor, if he had to suffer some indignity from him.

The British Museum recently spent £1.8m on the Warren Cup, a Roman silver drinking cup from around AD 50, depicting two scenes, each set indoors: one of two males copulating on a mattress, the other of homosexual paedophilia. This is a rarity, because much of the homosexual imagery of the time was either hidden or destroyed.