CHAPTER 5

ETHNOMEDICINAL PLANTS OF WESTERN AND CENTRAL HIMALAYAS

CONTENTS

5.2 Medicinal Wealth and Traditional Medical System

5.3 Stages of Collection of Plant Parts

5.5 Cultivation and Conservation Aspects of Medicinal Plants

5.7 Medicinal Plants Remedies as a Source of Income

ABSTRACT

The Himalayan medicinal plants are major source of traditional herbal health care for the local inhabitants since a long back which provide cure to the poor and tribal population of these regions. There are different traditional medical systems prevalent in Western and Central Himalayan region of our country. The traditional herbalists play a major role in skillful utilization of wild medicinal plants with certain other combinations.

The Western Himalayan region is considered natural abode of certain important medicinal plants as well as rare, threatened and endangered plants of medicinal value. The climate and environmental conditions prevail in the Himalayan region are suitable for high quality drug development.

The western and central Himalaya shares more than 1000 species of medicinal plants of which maximum herbs followed by shrubs and trees are mainly used in traditional medicine. A maximum number of underground parts followed by leaves, whole plant, bark and wood, etc. are the common plant parts used in the preparation of remedies.

According to published literature a maximum of 1338 species of ethnomedicinal plants were reported from Uttarakhand by Pande et al. (2006) followed by 948 species from Jammu & Kashmir state by Gairola et al. (2014) and 643 species from Himachal Pradesh by Samant et al. (2007).

This chapter on ethnomedicinal plants of western and central Himalayas is a review of information available on medicinal plants from various sources and from the published literature which will be highly useful for researchers and scientists associated with ethnobotany, traditional medical practitioners and other allied fields of plant sciences.

5.1 INTRODUCTION

Elementary needs of pre-historic man were fulfilled by the plants of his surroundings. He was totally dependent on these plants for food, medicine and other domestic purposes. This interaction between man and plants in day- to-day life continued over long period and a systematic study of its nature came to be known as a science of ethnobotany in recent past. The plant wealth constitutes a good source of food, medicines, shelter and other necessities for the human beings since the time immemorial. The rate and scale of environmental changes brought about by increasing population pressure and fast development activities are threatening the Himalayan ecosystem, thereby causing loss of habitats, which are rich in characteristic flora and fauna. Conservation of wild medicinal plants will play a vital role to protect the existing diversity of medicinal flora and will be helpful for sustainable exploitation of these valuable resources in the Himalaya for overall economic development of these regions (Kaul, 1997; Chaurasia et al., 2007).

India is very rich in diverse biological wealth. About 17,000 species of higher plants reported from the forests of India, of which 7500 are known for their medicinal properties (Shiva, 1996). About 340 drugs and their indigenous use were reported about 300 B.C. in Charak Samhita (Prajapati et al., 2003). The World Health Organization (WHO) has listed 21,000 plants of medicinal use around the world.

The great Indian Himalaya called as “abode of snow” is a mountain range in the Indian subcontinent which separates the Indo-Gangetic plain from the Tibetan Plateau. This range is home to 9 of the 10 highest peaks on Earth, including the highest Mount Everest. The Indian Himalaya is spread over 13 States in India having a total of about 5,94,427 km2 geographic area which is about 18% area of the country. Over 50 millions people (over 6% of total Indian population) live in these areas. Length of Indian Himalaya is about 2,400 km and width is around 240-320 km.

5.1.1 THE CENTRAL WESTERN HIMALAYA

The Central Western Himalaya covers the Uttarakhand, which includes the major divisions of Kumaun and Garhwal. A number of tribes and people - Protoaustroloids, Mundas, Kiratas, Mongoloids, Indo-Aryans, Khasas, Sakas and others have developed a variety of culture and knowledge in this region since a long back. It is interesting to know that the region has more powerful local gods and goddesses than the Brahmanical gods. The cultural groups of the Central Himalayan Region include the Kumaunis, Garhwalis, and some tribes like Bhotias, Rajees, Tharus, Boxas, Jaunsarees, which have their own different cultures, traditions, languages, customs, etc. Thus the Central Himalayas provide excellent opportunities for studying the Traditional Knowledge Systems (Agrawal and Kharakwal, 1998).

The Indian Central Himalayan Region is very rich in medicinal wealth and traditional knowledge. It is recognized as one of the world’s top 12 mega biodiversity regions, and possesses rich flora that includes about 45,000 species of plants. Majority of them are known for medicinal values. There are different traditional health care systems that exist in this region and are known as classical Indian systems of medicines. About 95% medicinal plants are collected from naturally growing forest areas. The collection process is usually devastative because of the use of plant parts like roots (29.6%), leaves (25.8%), barks (13.5%), wood (2.8%), rhizome (4%), and whole plants (24.3%). Vegetation of the region can be categorized from the tropical deciduous to the alpine pastures. Most of the floral species are vulnerable to extinct. It has been estimated that over 350 species of plants are vulnerable in this region, out of which, 161 species belongs to rare and threatened categories (Pondhani et al., 2011). The vegetation of Indian Central Himalayan Region is considered as rich source of medicinal plants; however, various factors such as habitat devastation, over grazing, illegal exploitation, changing climate, etc., decreased the availability of medicinal plants in the wild (Maikhuri et al., 1998). The Uttarakhand State was declared ‘Herbal State’ in 2003 and the State Government has now started cultivating medicinal plants in the suitable agro-climatic zones of mid-altitudes and the high altitudes.

The western Himalayan region has rich heritage of medicinal and aromatic flora which covers about 3,29,032 km2 lying in the west of Nepal. 67.5% of total area lies in Kashmir and about 17% area lies in Himachal Pradesh. The hilly districts of Uttarakhand state, i.e., Kumaun and Garhwal regions cover a total area of 51,125 km2. The Western Himalaya can be divided into following climatic zones:

- Tropical zone: up to 1000 m above mean sea level;

- Sub tropical zone: between 1001 m to 1800 m above mean sea level;

- Temperate Zone: between 1801 m to 2800 m above mean sea level;

- Alpine temperate: between 2801 m to 3800 m above mean sea level;

- Glacial temperate: above 3800 m above mean sea level.

A number of plants of medicinal value were reported from different zones. Some common species of these zones are given as under:

5.1.1.1 Tropical and Sub-tropical Zone < 1800 m

Justicia adhatoda, Achyranthes aspera, Mangifera indica, Apium graveo- lens, Rauwolfia serpentina, Acorus calamus, Calotropis gigantea, Asparagus adscendens, A. racemosus, Azardirachta indica, Artemisia absinthium, A. japonica, Tagetes minuta, Berberis asiatica, Rorippa indica, Bauhinia variegata, B. vahlii, Caesalpinia decapetala, Cassia fistula, Terminalia alata, T. arjuna, T. chebula, Cyperus rotundus, Dioscorea bulbifera, Emblica officinalis, Swertia angustifolia, Hypericum perforatum, Curculigo orchioides, Ajuga parviflora, Mentha arvensis, M. piperata, Ocimum canum, O. sanctum, Salvia plebeia, S. lanata, Cinnamomum tamala, Aloe barbadensis, Woodfordia fruticosa, Tinospora cordifolia, Syzygium cuminii, Malaxis acuminata, Zizipus mauritiana, Prinsepia utilis, Rubia cordifolia, Zanthoxylum armatum, Sapindus mukorossii, Bergenia ligulata, Bacopa monnierii, Withania somnifera, Atropa belladonna, Urtica parviflora, Hedychium spicatum, Elaeagnus conferta, etc.

5.1.1.2 Temperate Zone 1801-2800 m

Ferula jaeschkeana, Heracleum candicans, Asparagus filicinus, Ainsliaea aptera, Berberis aristata, Betula alnoides, Sagina saginoides, Corylus jacquemontii, Rosularia rosulata, Gentiana kurroo, Skimmia laureola, Geranium nepalense, Elsholtzia fruticosa, Rhododendron arboreum, Malva verticillata, Oxalis corniculata, Phytolacca acinosa, Polygala sibirica and Taxus baccata subsp. wallichiana, etc.

5.1.1.3 Subalpine Zone 2801-3800 m

Allium humile, Bunium persicum, Malaxis muscifera, Carum carvii, Geranium wallichianum, Angelica glauca, Archangelica himalaica, Bupleurum falcatum, Heracleum lanatum, Arisaema flavum, Saussurea auriculata, S. costus, Tanacetum gracile, T. tenuifolium, T. tomentosum, Impatiens glandulifera, Arnebia benthamii, Eritrichium canum, Rhododendron campanulatum, Ribes orientale, Polygonatum multiflorum, P. verticillatum, Plantago depressa, Aconitum ferox, A. leave, A. heterophyllum, A. falconeri, Pedicularis pectinata, Polygonatum verticillatum, Dactylorhiza hatagirea, Picrorhiza kurrooa, etc.

5.1.1.4 Alpine Zone > 3800 m

Cortia depressa, Selinum tenuifolium, Heracleum wallichii, Inula royleana, Saussurea graminifolia, S. obvallata, S. simsoniana, S. gossypiphora, Arnebia euchroma, Corydalis meifolia, C. govaniana, Iris kumaonensis, Fritillaria roylei, Polygonum affine, Rhododendron anthopogon, Rheum australe, R. moorcroftianum, R. webbianum, Dactylorhiza hatagirea, Picrorhiza kurrooa, Aconitum heterophyllum, A. rotundifolium, A. violaceum, A. spicatum, Delphinium cashmerianum, D. vestitum, Nardostachys grandiflora, etc.

Utilization of plants for medicinal purposes in India has been documented long back in ancient literature. However, organized studies in this direction were initiated in 1956 (Rao, 1996) and off late such studies are gaining recognition and popularity due to loss of traditional knowledge and declining plant population.

In the interior areas of western Himalaya plants become the only source of medicine and well being. Due to remoteness and lack of modern health facilities dependence on plants for medicine is very high in the interior parts of Himalaya. The role of market economy in depletion of traditional knowledge has been well documented in many parts of Himalaya (Uniyal et al., 2003). Thus many important leads to drug discovery may be lost in absence of proper documentation.

The demand of herbal products and plant-based drugs has sudden rise across the world resulting in the heavy exploitation of medicinal plants in recent years. Habitat degradation, unscientific, unsustainable harvesting and over-exploitation to meet the demands of the mostly illegal trade in medicinal plants have already led to the extinction of more than 150 plant species in the wild (Singh and Rawat, 2011; Dhar et al., 2000). More than 90% of medicinal plants used in the herbal industries are exploited from the wild and about 70% of the medicinal plants of Indian Himalaya are subject to unscientific and destructive harvesting and the majority of these plants and their stems from alpine and sub-alpine zones of the Himalaya (Singh and Dey, 2005). The significance of ethnobiological knowledge on plants and ecology can provide leads for new paths in scientific research and conservation has received attention in resource management worldwide.

5.1.2 UTTARAKHAND

The Uttarakhand is located between latitude 29°5’-31°25’N and longitude 77°45’-81° E covering an area of 53,485 Km2. It is situated between 300 to 7817 m above mean sea level which resulted in complex diversity in topography, meteorology, flora and fauna. The main tribal groups living in Uttarakhand are Bhotia, Rajees, Tharu and Boxas. The State covers the major part of Indian Central Himalaya (Pande et al., 2007).

About 2,500 plants species are being used in different system of medicines in India and 1750 herbal species are reported as native to the Indian Himalaya, in which western Himalaya has a share of about 1000 species which are still in use. This proportion of medicinal plants reported to be highest proportion of known medicinal plants of any country in the world against existing flora of that respective country (Kala, 2002). According to National Medicinal Plant Board about 1200 species are estimated to have medicinal value in Uttarakhand state. The natural environment of this region has been affected to a great extent due to overgrazing, cultivation in slopes, sub marginal lands, destruction of forest, change in weather pattern and unplanned development activities like construction of roads, buildings and tourists’ resorts, etc. The indiscriminate and unscientific exploitation have severely disturbed the ecological balance (Pandey et al., 2006).

The Himalayan range in the northern part of India harbors a great diversity of medicinal plants. Of the approximately 8000 species of angio- sperms (40% endemic), 44 species of gymnosperms (16% endemic), 600 species of pteridophytes (25% endemic), 1737 species of bryophytes (33% endemic), 1159 species of lichens (11% endemic), 6900 species of fungi (27% endemic) have been reported in the Indian Himalaya (Singh and Hajra, 1996). Among these some of 1748 species (1685 angiosperms, 12 Gymnosperms, 51 Pteridophytes) including 1020 herbs, 335 shrubs and 330 trees are known for their medicinal properties (Samant et al., 1998a), 675 species are wild edible (Samant and Dhar, 1997), 118 medicinal plants yielding essential oil, 279 species of fodder plants, 155 sacred plants species (Samant and Pant, 2003), 121 rare, endangered plants (Nayar and Sastry, 1987, 1988, 1990). Out of total 1748 medicinal plants reported from IHR 31% are native, 15.5% are endemic and 14% threatened. About 1717 species of them are reported from 1800 m elevation range. The state of Uttarakhand in the central -western Himalaya, still maintains a dense vegetation cover (65%). On regional scale maximum number of medicinal plants has been reported from Uttarakhand followed by Sikkim and North Bengal (Kala, 2004; Kala and Mathur, 2002). About 337 species of medicinal plants reported from the trans-Himalaya which is low as compared to other areas of the Himalaya due to the divergent geography and ecological conditions (Kala, 2002, 2005a).

5.1.3 HIMACHAL PRADESH

Himachal Pradesh located in the north-western Himalaya gifted with the lush green beautiful landscapes and natural scenarios. It has 55,673 Km2 geographical area (about 1.7% of the country’s geographical area), which lies between latitude 30o22’40” to 33°12’40” N to longitude 75°45’55” to 793o04’20” E and includes parts of Trans and Northwest Himalaya covering 9% of total Indian Himalayan Region. Like other parts of IHR the state Himachal Pradesh has a representative, natural and socio-economically important biodiversity in between large altitudinal range (200-7109 m) with diverse habitat, species, populations, communities and ecosystems. The vegetation of Himachal Pradesh is varied from tropical in the lower parts to subtropical (500-1800 m) to temperate (1801-2800 m) to subalpine (2801-3800 m) to alpine above 3800 m which is usually found at 3300 m in the valleys. More than 3500 flowering plants have been reported from HP (Chowdhery, 1992), of which almost 500 plants are believed to be of medicinal importance (Chauhan, 2003). Samant et al., (2007) reported a maximum number of about 643 species of medicinal plants from Himachal Pradesh, of these 417 were found in the tropical and sub-tropical zone (<1800 m), followed by 356 spp. in the temperate zone (1801-2800 m), 303 spp. in subalpine zone (2801-3800 m) and 158 spp. in alpine zone (>3800 m). Forest department of the Himachal Pradesh estimated more than 3500 species of flowering plants, out of which about 800 species are known to be used for medicinal purposes within and outside the State.

5.1.4 JAMMU AND KASHMIR

Jammu and Kashmir state is most beautiful place on the earth which is expanded over an area of 2,22,235 km2. It is surrounded by China in the north, by an autonomous region of Tibet in the east, by Himachal Pradesh and Punjab in the south, and by the Pakistani city Rawalpindi towards the west. Afghanistan is located towards the North Western side of J&K. Out of the 2,22,235 km2 are 48% area is under India, 35% is under Pakistan and rest 17 per cent is under the control of China.

Thus Jammu and Kashmir has remaining actual geographic area of 1,01,387 km2 and situated in between altitudes range 1,700 to 5,500 m above mean sea level. It lies between latitude 32°17’ and 37°05’ N. and longitude 72°31’ and 80o20’ E. The State is divided into three geographic

regions viz. Jammu, Kashmir Valley and Ladakh. The higher areas are covered by Pir Panjal, Karakoram and inner Himalayan range of mountains. The important rivers of the State are the Chenab, the Tawi, the Jhelum and

the Indus. Vegetation and climate can broadly be categorized into subtropical, temperate and alpine zones with wide diversity of flora and fauna.

It is reported that about 572 plant species belonging to 109 different families have medicinal value. The forest covers an area of 20,230 Sq. Kms. which constitutes 19.95% of geographical area of the State. There are five forest types found in the State Viz. Subtropical Dry Evergreen, Himalayan Moist Temperate, Himalayan Dry Temperate, Subtropical Pine and Sub-alpine and alpine Forests. Forest is mainly found in Kashmir and Jammu divisions while Ladakh is devoid of forest. According to Gairola et al. (2014) a total of 948 plants of medicinal use were recorded from the whole Jammu & Kashmir state.

The traditional medicine has a long history of utilization by the tribal

communities of the region. Some significant contributions on biological resources include Sharma (1991), Naqshi et al. (1992), Singh (1994), Siddique et al. (1995), Kaul (1997), Virendra et al. (2002), Ganaie and Nawchoo (2003), Khan et al. (2004), Tantray et al. (2009) and Malik et al. (2011a, b).

5.1.5 THE NORTH-WESTERN HIMALAYA THE TRANS HIMALAYA

The cold arid regions of India are called “Trans Himalayan region” lies in the western edge of the Himalayas. It comprises Ladakh in J&K, Lahaul and Spiti, Kinnaur, Pangi Valley of district Chamba in Himachal Pradesh, and Niti and Nelong Valley of Uttarakhand. The vegetation here is subjected to extreme climatic conditions such as temperature variation (low temperature), scanty rainfall, speedy winds, exposure to ultraviolet radiations, reduced oxygen levels, low humidity, and many small glaciers (Chaurasia and Gurmet, 2004).

The major part of Indian cold desert covers the Ladakh region of Jammu & Kashmir which lies between 32° 36’ to 36° 30’ North latitude and 74° 30’ to 80° 30’ East longitude. It covers approximately 68,321 sq. Km, besides 27,555 Sq. Km areas, which is under illegal occupation of Pakistan and China (Ballabh and Chaurasia, 2006).

More than 85% of the area of Ladakh lies above 5000 m or more above mean sea level. The Indus River is the main river, which follows the course from southeast to northwest through the greater part of the country. The region is famous for several lakes viz. Pangongtso (4,384 m), Tsomoriri (4354 m), Tsokar, etc. Similarly a number of hot springs abound in Ladakh, of which Puga and Panamik are well known and Indus, Nubra, Changthang, Zanskar and Suru valleys are also famous.

5.2 MEDICINAL WEALTH AND TRADITIONAL MEDICAL SYSTEM

In India, over 7500 plants species are estimated to be used by approximately 4635 ethnic communities for human and veterinary health care across the various ecosystems ranging from Ladakh in the trans Himalayan cold desert to the southern coastal tip of Andaman & Nicobar Islands and from the deserts of Rajasthan and Kutch to the Hills of the north east. It is estimated that the medicinal plants used in different medical system are Ayurveda 1769 species, Folk medicine 4671 species, Homeopathy 482 species, Siddha 1121 species, Tibetan or Amchi 279 species and Unani 751 species.

The Himalayas are very rich in medicinal wealth and traditional medicinal knowledge. The Central Himalayan Region covers the new state of India, i.e., Uttarakhand, which is a storehouse of variety of herbs of medicinal and aromatic value. The Indian Himalayas alone supports about 18,440 species of plants of which about 45% are having medicinal properties. According to Samant et al. (1998b) out of the total species of vascular plants, 1748 spp. species are of medicinal importance. In the Himalayan regions the traditional medicine is generally prescribed by skilled person of the family very efficiently since a long back. The household ladies in Himalayan region use herbal drugs for most of the ordinary ailments of infants and children. The herbal drugs are generally available from their kitchen stock, kitchen garden or village fields and from the village bazaar.

The rhizome of Curcuma domestica (Haldi) is used for cuts, burns and scalds; the fruits of Piper nigrum (black pepper, Kali-mirch or gol-mirch) for colds and coughs; the fruits of Trachyspermum ammi (ajawain); and resin of Ferula spp. (heeng) for stomach troubles and whooping cough; the seeds of Sesamum indicum (Til) for ulcers and boils, etc., are well known to elderly housewives.

The infusion of the leaves of Ocimum sanctum (Tulsi) is used for colds and coughs and mild fever, fomentation with the hot leaves of Ricinus communis (Erand) and Aloe barbadensis (Geekuar) for relieving inflammations, swellings of joints and sprains, and many other home remedies are learnt traditionally in the home. The elderly persons, Pujari, Ojhas, and priests, etc., of the villages know certain herbal drugs, which grow nearby areas and try them effectively and free of cost without any hesitation against several common ailments and diseases.

Traditional herbalists are mostly illiterate but highly skilled and have considerable knowledge of the herbal drugs and their uses. They keep stocks of crude drugs for sale and prescribe these for common ailments. Usually the traditional herbalists maintain small shop of herbal remedies. There is another kind of herbalist, who is a wanderer. Among these there are two categories: those who administer a ground mixture of herbal drugs, and those who prescribe and also supply the herbal drugs as such.

The herbalists also store their crude drugs in glass jars and often display them towards roadside. They procure drugs from North Indian established crude drug markets. They administer drugs mainly for various ailments and also as tonics and aphrodisiacs. The most commonly available drugs are the tuberous roots of Orchis species. (Salam panja or Salam gatta), the roots of Asparagus spp. (Satawar), Withania somnifera (Ashwagandha), the fruits of Tribulus terrestris (Chota gokhru), and Pedalium murex (Bara gokhru), seeds of Mucuna pruriens (Kiwanch), Entada pursaetha (Chian, gila), stems of Tinospora cordifolia (Giloya), the tubers of Pueraria tuberosa (Vidari kanda), and others.

The herbalist also administers the herbal drugs directly without pounding; they keep only a limited number of crude drugs for day-to-day use. The common drugs of this category are fruits of Terminalia chebula (Harra), T. bellerica (Bahera), Emblica officinalis (Awanla), Helicteres isora (Marorphali), bark of Symplocos species (Pathani lodhra), roots of Withania somnifera (Aswagandha nagori), and seeds and oleoresins of various plants. The herbalists in hilly regions often use certain crude drugs procured from the alpine zones, like Rheum spp. (Dolu), Aconitum heterophyllum (Atis), Picrorhiza kurooa (Karu), Angelica glauca (Chora or gandrayan), Nardostachys jatamansi (Mansi), and the aromatic leaves of Allium govanianum and other Allium spp. (Uambu or Jamboo), and many others.

The traditional medical system exists in Nepal, Ladakh, Lahaul and Spiti, Eastern Himalayan States and some tribal regions of Uttarakhand is known as “Amchi system of medicine” (based on Tibetan Medicine) and the practitioners are called Amchis (Buddhist medicine man-Superior of all). Amchi medicine is based on skillful uses of plants, minerals and animal products. The origin of Amchi medicine is traced back to India, where more than 2500 years ago Lord Budha delivered a medical practice called Bzi (Chatus tantre) which was translated in Tibetan language during 8th century AD by Acharya Chandrananda and Varochana. In order to popularize these texts in Tibet, the senior Yusthog Youthan Gonbo had made some changes in it to make it harmonious with the culture and environment of Tibet. Since then this system is very popular in Tibet and in most parts of the Himalayan belt. This system was introduced in cold arid zones during 10th/11th century AD approximately (Chaurasia et al., 2007).

The traditional practitioners in the Himalayan regions are looking after more than 80% of public health. The herbal healers have not only theoretical texts but also practical experience handed over from generation to generation. They have also a reputation of having high ethical standard in social system. Generally single herbal preparation and combinations of two or more herbs are prescribed and administered (Kala, 2002; Ballabh and Chaurasia, 2008; Chaurasia et. al., 2000).

5.3 STAGES OF COLLECTION OF PLANT PARTS

Potency and efficacy of medicinal plants depend upon collection/harvesting of different plant parts at their right stage (Chaurasia et. al., 2007).

5.3.1 ROOTS, RHIZOMES, TUBERS AND BULBS

The underground parts are the storage organs of the plant and accumulate active bioconstituents during summer months. Roots and rhizomes of the perennials are usually harvested after two to five years of growth either at the end of growing season or in the beginning of growing season. The underground parts of annuals are not generally collected.

5.3.2 AERIAL PARTS

These include all the parts of the plant growing above ground - stems, leaves, flowers. Stems are usually cut just above ground at the beginning of flowers while the perennials may be cut higher above ground to encourage further crops. Leaves are harvested throughout the growing season. Usually tender or young leaves are considered to have maximum content of bioactive constituents. Similarly flowers or the entire inflorescences are collected at the beginning of flowering period.

5.3.3 FRUITS AND BERRIES

These plant parts are collected when they are fully ripened. They are picked individually or in bunches.

5.3.4 SEEDS

Seeds are usually collected when fruits/berries fully mature and seeds are gathered before scattering.

5.3.5 BARK

This plant part is collected either in spring when the trees or shrubs start to sprout or in autumn when they shed their leaves because during this time the flow of sap is considered to be a maximum and barks readily detach from the wood.

5.4 STORAGE OF RAW MATERIALS

Processing and proper storage of medicinal plants parts are the most important steps for retaining maximum potency and quality. Under ground parts/ leaves/stems/bark are thoroughly washed, cleaned and dried in shed or ovens at proper temperature. Similarly fruits and seeds should be properly dried.

Storage of raw materials is very important for maintaining the quality of crude drugs. Leaves, roots, flowers and other plant parts should be stored in sterilized, dark glass containers with airtight lids or they may also be stored in brown paper/cotton bags and should be kept in dry and cool places to protect from insect damage and molds.

5.5 CULTIVATION AND CONSERVATION ASPECTS OF MEDICINAL PLANTS

It has been reported that certain species of commercially viable medicinal plants has been successfully cultivated in central and western Himalayan regions. Maikhuri et al., (1997) studied the cultivation of medicinal plants of Indian central Himalayan region. Atal and Kapur (1982) studied the cultivation aspects of 71 species of Jammu & Kashmir. Jee Vir et al. (1984) reported 26 medicinal plants under cultivation in Rajaori district of Jammu & Kashmir. Silori and Badola (2000) discussed cultivation of 12 species of commercially viable medicinal plants of Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve. It has been reported that in Uttarakhand about 3000 farmers involved in cultivation of medicinal plants.

Due to increase of human interventions, tourist’s activities, construction of roads and buildings, unscientific exploitation of natural resources, water and wind erosion in the Himalayan region the loss of existing medicinal flora has increased manifold. Certain important species of medicinal plants has already kept in red data book of IUCN. Ex-situ and in-situ conservation and sustainable utilization of these valuable resources is need of present hour. Some conservation strategies suggested by various workers on conservation aspects are as under:

i. Quantitative assessment and identification of threatened and commercially viable medicinal plants should be done with a particular attention to those species on which people’s livelihood depends.

- There is urgent need of prioritizing study areas on limiting factor of loss of valuable medicinal flora.

- There is need to adopt more realistic approach through recent techniques like RS and GIS by continuous monitoring, suggestion and amendment on conservation plan.

- Implementation of environmental education awareness among society towards conservation of valuable medicinal resources.

- By adopting traditional success mechanism with regards to conservation strategies of life saving drug yielding medicinal resources.

- Establishment of well-equipped laboratories in the Indian Himalayan States at different altitudes for identification of eco-physiological characteristics of alpine and Himalayan medicinal plants.

- By adopting in-situ conservation plan for valuable threatened and endangered medicinal plants of Indian Himalaya.

- To promote community based conservation.

- By adopting ex-situ conservation mainly tissue culture and MAP nurseries/gardens, etc. to conserve natural resources.

- Establishment of herbaria which has an indirect role in detec tion, assessment and monitoring of important rare and threatened medicinal plants species there by augmenting ex-situ and in-situ conservation.

- To develop conservation technology, i.e., in vitro and agro-technology for commercially viable threatened and economically important medicinal plants to enhance mass production as well as reduce pressure on natural habitat.

- A P4 management strategy of prediction, prevention, prescription and public awareness need to be adopted to stem out the tide of biological invasion.

It is expected that this chapter will be of much significance to the ethno- botanists and workers in related fields in view of the following.

- It will bring forth the heretofore-unknown knowledge on ethnome- dicinal plants of Central and Western Himalaya.

- It will bring forth the knowledge of the ways and means in which tribal people are utilizing different vegetational resources of their surrounding environment for different purposes.

- It will underline the strategy for better and balanced utilization of plant resources in the tribal community in the Central and Western Himalayas.

- It will also underline the strategy for sustainable utilization of plant resources and conservation of rare, threatened and endangered medicinal and other useful ethnomedicinal flora of Indian Himalayan Region.

5.6 REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

The history of Indian medical botany is traced back to the Vedic era. India is very rich in ethnobotanical information, which can be tapped for information on medicinal, edible and other folk-lore of plants. According to Jain and Mitra (1991), “Ethnobotanical knowledge is very ancient in India. Ever recorded ethnobotany of India might well be among the earliest in the world.”

A brief account of literature review on ethno-medico botany in the western and central Himalaya which has been studied by a number of workers since a long back is as follows.

Stewart (1916-17) studied the flora of Ladakh and Western Tibet and reported various useful plants. Many useful plants of Himalaya were mentioned in “Wealth of India- Raw Materials” (Annonymus, 1948-1976). Medicinal plants of Himalayan region were studied by Kapoor et al. (1957). Gupta (1960a) presented ethnobotanical study of some useful and medicinal plants of Garhwal Himalaya. Gupta (1960b) studied useful and medicinal plants of Nainital district of Kumaun Himalaya. Juyal and Uniyal (1960) studied medicinal plants of commercial and traditional importance in Bhillanganga valley of Tehri Garhwal. Juyal and Uniyal (1966) studied medicinal plants of Bhagirathy valley.

Gupta (1962) studied the medicinal plants of west Himalaya. S. K. Jain, considered as father of modern ethnobotany of India, studied the ethno- botany of different states of India in collaboration with other workers and he covered many species of Himalaya in his literature (Jain, 1981, 1987, 1991). Ahluwalia (1965) documented medicinal plants of Toon division in Har-ki-Dun areas.

Shah (1971) conducted medico-botanical study of Dronagiri the mythic hill in Kumaun. Shah and Joshi (1971) conducted an ethnobotanical study of Kumaun region of India. Naithani (1973) documented medicinal plants of western Garhwal. Raghunathan (1976) compiled and edited a book entitled “The study of herbal wealth of Ladakh.” Plants along with their uses were described by Singh and Arora (1978). Koelz (1979) gave notes on ethno- botany of Lahaul-Spiti area in Himachal Pradesh. Mehrotra (1979) surveyed medicinal plants around Kedarnath shrine of Garhwal Himalaya. Shah et al. (1980) surveyed some medicinal plants of Dharchula block in Pithoragarh district. Gupta et al. (1980, 1981) carried out phytochemical screening of ethnobotanically important plants of Ladakh.

Srivastava et al. (1976, 1981, 1982, 1986) studied the various aspects of ethnobotany of Ladakh. Shah (1981) studied the role of ethnobotany in relation to medicinal plants in India. Nautiyal (1981) highlighted traditional use of some medicinal plants of Garhwal Himalaya. A preliminary study of medicinal plants from Suru valley in Ladakh was carried out by Uniyal (1981). Joshi et al. (1982) highlighted some medicinal plants of Rudranath Bugyal (District Chamoli). Kak (1983) presented ethnobotany of Kashmiris. Rajwar (1983) studied low altitude medicinal plants of south Garhwal. Chopra et al. (1984) referred some poisonous plants of the Himalayan region. Dar et al. (1984) conducted a survey on ethnobotany of Kashmir- Sind valley and reported the medicinal use of 57 species. Jee et al. (1984) conducted taxo-ethnobotanical studies of 36 species in the rural areas of Rajouri district. They reported 36 medicinal plants, 17 fodder plants, 16 fuel and fire wood plants along with 26 species under cultivation. Brown (1984) formulated methods for collection of data of botanical life forms and folk- taxonomy. Viswanathan and Mankad (1984) published a paper on medicinal plant of Ladakh. Gaur et al. (1984) presented a survey of high altitude medicinal plants of Garhwal Himalaya. Jain and Puri (1984) conducted an ethnomedicobotanical survey of Jaunsar-Bawar, a hilly tribal inhabited area in Uttarakhand and documented the traditional medicinal use of about 100 plants by the local Jaunsari tribe against treatment of various ailments. Maheshwari and Singh (1984) contributed to the ethnobotany of Boxa tribes of Bijnor and Pauri Garhwal district. Malhotra and Balodi (1984) listed wild medicinal plants in the use of Johari tribals. Malhotra and Bashu (1984) presented a preliminary survey of plants resources of medicinal and aromatic value from Almora district. Rajwar (1984) highlighted exploitation of medicinal plants of Garhwal Himalaya.

Mishra (1985) studied medicinal plants of Pauri Garhwal. Negi et al. (1985) conducted an ethnobotanical study on economic importance of some common trees in Garhwal Himalaya. Ansari and Nand (1985) reported certain medicinal plants of Pauri Garhwal region. Kaul et al. (1985) studied an ethnobotany of Notrthwest and Trans-Himalaya; contribution to the wild food plants of Ladakh. Purohit et al. (1986) conducted an ethnobotanical study on some medicinal plants used in skin diseases from Raath, Pauri Garhwal Himalaya. Gaur et al. (1986) highlighted the folk utility of multieconomic tree Eunymus tingens Wall. in Raath region of Garhwal Himalaya. Uniyal and Joshi (1986) highlighted traditionally used family planning drug “Babila ghass” from Garhwal Himalaya. Dhasmana (1986a) documented the medicinal plants of family Lamiaceae of Pauri town and adjacent area of Garhwal Himalaya. Dhasmana (1986b) documented the medicinal plants of family Compositae of Pauri town and adjacent area of Garhwal Himalaya. Aswal and Mehrotra (1987) studied ethnobotany and flora of Lahul valley (Northwest Himalaya). Ethnobotany of Kashmir was investigated by Kachroo and Nahvi (1987). Rao and Hajara (1987) gave a reference of Amchis of Ladakh. Medico-ethnobotanical survey carried out by CCRAS in Ladakh along with other states was compiled by Raghunathan (1987). Sand and Badola (1987) conducted an ethno-botanical study of J&K state of North-West Himalaya. Shah (1987) submitted a PhD thesis on ethnobotany in the mountain region of Kumaun Himalaya. Uniyal and Issar (1988) studied the utility of hitherto unknown herbal drugs traditionally used in Ladakh. Gaur and Tiwari (1987) presented ethnobotanical study of some little known medicinal plants of Garhwal Himalaya. Dhasmana (1987) documented the medicinal plants of Pauri town and adjacent area of Garhwal Himalaya.

Badoni (1987-88) studied the ethnobotany of hill tribals of Uttarkashi and plants used in rituals and psychomedicinal practices.

Bisht et al. (1988) presented an ethnobotanical study on folk medicine of Arakot valley in Uttarkashi. Kalakoti and Pangety (1988) described eth- nomedicine of Bhotiya tribes of Kumaun Himalaya. Singh (1988) highlighted ethnobiological treatment of piles by Boxas of Uttar Pradesh. Aswal and Goel (1989) reported less known medicinal uses of western Himalaya. Kaul et al. (1989) investigated some aspects of ethnobotany of ‘Pahari’ community living in Basohli-Bani region of Jammu and Kashmir and reported uses of 39 plant species. Kimothi and Shah (1989) described some medicinal plants of Gopeshwar-Tungnath region. Lal et al. (1989) had given a contribution to the medicinal plants lore of Garhwal region. Irshad et al. (1989, 1990) discussed ethnobotany of Ladakh India. Tewari et al. (1989) highlighted Lobelia pyramidalis Wall. as a drug for treatment of asthma from Himalayan region. Badoni (1990) carried out an ethnobotanical study of Pinswari community. Kapahi (1990) investigated ethnobotany of Lahul in Himachal Pradesh. Katiyar et al. (1990) reported nutritive value and medicinal beliefs of some novel wild plants of Gurez valley in Kashmir. Kaul et al. (1990) studied Home remedies for Arthritis in Kashmir Himalaya. Kumar and Naqshi (1990) studied the ethnobotany of Pirpanjal range of Banihal. Maheshwari and Singh (1990) discussed herbal remedies of Boxas of Nainital district. Mumgain and Rao (1990) studied some medicinal plants of Pauri Garhwal.

Ansari (1991) gave ethnobotanical notes on some plants of Khirsu in Pauri Garhwal. Bhattacharyya (1991) studied the ethnobotany of Ladakh and reported 57 species used as vegetable, for ceremonies, personal hygiene and as fodder. Kapur (1991) studied the traditionally important medicinal plant of Dudu valley and reported 71 species used by Gujjars, Bakarwals and Gaddhi tribes. Sharma (1991) reported some economic plants from the Jammu &Kashmir areas, which are used against rheumatic pain by different ethnic groups like phalaris, Gujjars Bakarwals, Dards and Ladakhis. Jain and Saklani (1991) presented observations on the Tons valley region in the Uttarkashi district of North-West Himalaya. Joshi and Uniyal (1991) presented folk medicinal importance of Peonia emodi and its cultivation strategy from western Himalaya. Kaul et al. (1991) contributed to the ethnobotany of Padaris of Doda in J&K State. Ara and Naqshi (1992) conducted ethno- botanical studies in Gureij valley of Jammu and Kashmir Himalaya. Aswal (1992) reported less known medicinal uses of 3 plants of Kumaun Himalaya. Gohil and Qadri (1992) studied medicinal plants of Kargil (Ladakh) used by Balti, Dard and Brokpa races. Gaur and Singh (1993) studied ethnomedici- nal plants of Mandi district, Himachal Pradesh. Kapahi et al. (1993) reported folklores of 56 plants species belonging to 50 genera and 28 families and their mode of administration from the area. Kapur (1993) studied ethno- medicinal plants of Kangra valley (Himachal Pradesh). Navchoo and Buth (1992) studied the medicinal, edible, fodder and fuel plants of Ladakh- used by the locals. Singh and Maheshwari (1992) presented traditional remedies for snakebite and scorpion sting among the Boxas of Nainital district. Singh and Maheshwari (1993) studied the phytotherapy for diphtheria by the Boxas of Nainital district. Datt and Lal (1993) studied some less known medicinal uses of plants of Pithoragarh of Kumaun Himalaya. Dhar and Siddique (1993) presented ethnobotanical studies and biological diversity of Suru valley (Zanskar). Pande (1993a) studied the use of Amees as traditional drug of Uttarakhand. Pande (1993b) studied the use of Ganjiyatri as traditional drug of Uttarakhand.

Pande (1994) studied the use of a traditional medicinal plant Kubjak of Uttarakhand Himalaya. Mehta et al. (1994) studied the folklore medicinal plants of Talla Johar of Eastern Kumaun. Negi (1994) studied the ancient traditional therapeutic wealth of Pauri and Tehri Garhwal. Joshi et al. (1994) studied Dioscorea kumaunensis Kunth. a new source of antirheumatic drug from Kumaun Himalaya. Samant and Mehta (1994) studied the folklore medicinal plants of Johar valley. Bisht (1994) had written a Hindi article regarding usefulness of Pyrecantha sp. as cardiac tonic. Shah (1994) presented ethnobotany of some well known Himalayan Compositae. Singh and Maheshwari (1994) studied the traditional phytotherapy of some medicinal plants used by the Tharus of Nainital district. Singh et al. (1995) studied ethnobotanical work of Indus valley and botanical curiosities in the alpine flora of Khardungla. Pant and Pande (1995) conducted an ethnobo- tanical study on medicinal flora of Tharu tribal pocket in Kumun region. Joshi et al. (1995a) highlighted indigenous system of medicine and drug abuse. Joshi et al. (1995b) discussed Taxus baccata as an emerging anticancer plant. Farooquee and Saxena (1996) studied the conservation and utilization of medicinal plants by the local inhabitants of high hills of central Himalaya and reported that fifteen cooperatives with a 1992 membership of 7009 herb collectors and sales people exist in the Dharchula block, and marketing is done through two specialist government agencies. Joshi et al. (1996-97) have given botanical identification of new folk medicine for snakebite from Kumaun Himalaya. Kapur and Nanda (1992, 1996) reported certain medicinal plants used by the tribal people of Bhaderwah hills of Jammu. Kapur (1996a, b) reported medicinal plants in Bhaderwah hills of Jammu Province. Kapur and Singh (1996) published 88 traditionally important plants in Udampur district of Jammu. Plants used as ethnomedi-cine and supplement food by the Gaddis of Himachal Pradesh was given by Lal et al. (1996). A book entitled “Amchi System of Medicine - A Research Profile” was compiled and edited by Goyal et al. (1996-1998). A total of 111 ethno-medicinal plants of Kashmir and Ladakh were documented by Kaul (1997) and published a book entitled “Medicinal Plants of Kashmir & Ladakh.” Purohit (1997) studied the Himalayan medicinal plants focus on Uttarakhand. Singh et al. (1997) mentioned plant biotechnology and herbal flora of Ladakh and also published a paper on medicinal flora of Indian cold desert.

Singh and Rawat (1998) had compared the traditional versus commercial use of wild medicinal plants of great Himalayan National park. Kaul et al. (1998) have carried out an investigation on “Crude Drugs of Zanskar” (Ladakh) used by Amchi system of medicine. Biodiversity in herbal medicines was studied by Singh et al. (1998). Gurmet et al. (1998) discussed some traditional medicinal plants of Khardungla and Changla used in Amchi medicine of Ladakh. Maikhuri et al. (1998) discussed role of medicinal plants in the traditional health care system in the biosphere reserve. Saklani (1998) had presented traditional practices and knowledge of wild plants among ethnic communities of Garhwal Himalaya. Samant et al. (1998a) published a book on Medicinal plants of Indian Himalaya, diversity, distribution potential value. Singh and Pruthi (1998) reported biodiversity in herbal medicine. Ethnobotanical study of tribal areas of Almora district was carried out by Arya et al. (1999) and Arya and Prakash (2003). Chauhan (1999a) published a book on Medicinal and aromatic plants of Himachal Pradesh and discussed 174 plants and their medicinal uses in detail. Chaurasia et al. (1999, 2000, 2001, 2003, 2007) carried out extensive ethnobotanical survey of cold arid zones of Ladakh and Lahaul-Spiti and documented the important ethnobo- tanical information. Gaur (1999) gave an account of flora of Garhwal district along with ethnobotanical note. Kala and Manjrekar (1999) documented ethnobotanical and medicinal uses of 40 plant species from an ecologically fragile cold desert area of Lahaul-Spiti in Himachal Pradesh. Pande et al. (1999) edited a book on Ethnobotany of Kumaun Himalaya. K. K. Singh (1999) conducted ethnobotanical studies of the Tharus of Kumaun Himalaya. G. S. Singh (1999) documented a brief ethnobotanical account of 109 plant species belonging to 41 families and 86 genera found in Chhakinal watershed, Kullu District, in Himachal Pradesh, India, in the northwestern Himalayas. Out of the total recorded species, 1 belongs to the fungi, 1 to pteridophytes, 6 to gymnosperms and 101 to the angiosperms. Ninety-three species were found inside the forest boundary while 16 species were found near the settlements and farm fields. 73 medicinal plants were found to be used to cure several diseases. Other uses for food, timber, Fuel wood, fodder, religious ceremonies, etc. of 61 species besides medicinal value of some plants were also reported. Viswanathan (1999) worked out some edible and medicinal plants available in Ladakh. Kim et al. (1999) taken an ethnobo- tanical observation on Gymnosperms of Poonch district of J&K State.

Chaurasia et al. (2000) published a chapter on Ethnobotany of Ladakh Himalaya. Dhar et al. (2000) analyzed various aspects of medicinal plants of the Indian Himalayan region. 20 top ranking medicinal plants were identified for conservation in each life form. Joshi and Pandey (2000) discussed eth- nobotany of Tarikhet block of Kumaun Himalaya. Silori and Badola (2000) conducted a case study in the buffer zone of the Nanda Devi biosphere reserve, in the Western Himalaya and reported out of 71 families 90% of medicinal plants were cultivated on 78% of the total reported cultivated area (15.29 ha). It was estimated that an average family could earn between Rs. 4362 and Rs. 86,500 from the sale of medicinal herbs. Singh and Chaurasia (2000) published a paper entitled “Medicinal Flora of Indian Cold Desert.”

Samant and Palni (2000) attempted to prepare an inventory of essential-oil- yielding medicinal plants and analysis of species for distribution and utilization patterns, characterization of essential-oil-yielding medicinal plants and compilation of a list of species with known pharmacology, phytochemistry, cultural technique and propagation protocols.

Chaurasia et al. (2001) investigated potential aromatic flora of Himalaya cold desert: Ladakh and Lahul-Spiti. Samant et al. (2001) contributed a chapter on diversity, distribution indigenous uses of threatened medicinal plants of Askot wildlife sanctuary in west Himalaya conservation and management aspects. Kaul and Handa (2001) documented medicinal plants of crossroads of western Himalaya. Khullar (2001) had given some ideas on ferns in medicine and how to identify them. Kim and Kapahi (2001) given an ethnobotanical notes on some fern and fern allies of Jammu and Kashmir state, India. Pande and Joshi (2001) described the cultivated plants of Kumaun Himalaya used for medicinal purpose. Tripathi (2001) presented indigenous knowledge and traditional practices of some Himalayan medicinal plants. Badoni and Badoni (2001) presented a chapter on ethnobotanical heritage of Garhwal Himalaya in the book on Garhwal Himalaya, nature, culture and society. Nautiyal et al. (2001) reported medicinal plant resources of Nanda Devi biosphere reserve in the central Himalaya. A total of 100 medicinal plants were found to be used by local inhabitants of the region. Out of these 28 species were used to cure wound/boils; 22 species to cure gastritis and liver disorders; 19 species to relieve from muscular, rheumatic pain and headache; 16 species to cure cold, cough and promote disease resistance; 7 species to treat eye problems; 3 species to cure skin infection and 2 species to treat urinary disorders.

Ballabh (2002) submitted a thesis to Kumaon University, on ethnobotany of Boto tribe of Ladakh Himalaya, which consists 637 species (including 64 species from literature) belonging to 286 genera of 60 families of ethno- botanical importance including 314 species of ethno-medicinal use. Out of 314 ethno-medicinal plants, 54 species were used in fever, 47 species were used in veterinary medicines, 33 species were used in energetic medicine, weakness and health tonic, 29 species were used in cuts, wounds, swelling and bubo, 29 in diuretic and urinary problems, 26 in skin diseases and itching, 23 in dysentery and diarrhea, 22 in stomachache, abdominal and stomach disorders, 21 in cold and cough, 18 in kidney disorders, 16 in lungs problems, congestion and breathing problems, 14 against anti-worm, worm infestation and intestinal parasite, 12 as antiseptic and blood purification, 11 in asthma, bronchitis, eye and ear trouble and in swellings, 10 in gout, joints pain, insect repellant, against intoxication and poisoning, 9 in headache, mountain sickness and toothache, 8 as appetizer/digestive, jaundice and rheumatism and arthritis, 7 against infections, 6 in inflammation due to different poisoning, boils, burns, blisters and colic, 5 in ulcers, chest problems, 4 in bone-fracture, constipation, as hair dye, lipstick and shampoo, against menstrual regulation and pneumonia, 3 in insect-bite, worm infestation, insect-sting, dropsy, as cooling, against gall bladder and heart problems, pus formation, sprains, bleeding and antidote, 2 in pulmonary disorders, dermatitis, diphtheria, eczema, as febrifuge, foot and mouth diseases of cattle, leprosy, liver disorders, malaria, against muscular pain and as analgesic, 1 as astringent, backache, in delivery of child, nerve disorder, obesity and fatness, poultice, purgative, scrofula, sedative, sleeplessness, cold injury, throat problems, tumor, venereal disease, vomiting, waist pain. Negi et al. (2002) reported the use ethnomedicinal plants by a small tribal community (Raji) ‘Van Raut’ of Central Himalaya. A total 50 species were used for curing various ailments however, 3 plants were commonly used species by all the tribes. 11 major ailments viz. fever, spasm, delivery, jaundice, headache, toothache and skin diseases, etc. The maximum number of herbs is used in preparation of remedies followed by tree, shrub species and climbers. Most frequently used plants parts were roots (29%), followed by leaf (19%), latex and resin (12%), bark/stems (10%) and least number of flowers.

Negi and Subramani (2002) carried out ethnobotanical study in the village Chhitkul of Sangra valley in Kinnaur district of Himachal Pradesh. Beigh et al. (2003) studied plants used in traditional medicine of Kashmir Himalaya. Chandrasekar and Srivastava (2003) conducted ethnomedicinal studies in Pin valley National park, Lahul-Spiti, Himachal Pradesh. Kala (2003) has published a book on Tibetan use of medicinal resources in medicinal plants of Indian Trans-Himalaya. A total of 337 plant species, 38 species of animals and 6 minerals were recorded. Uniyal (2003) described the indigenous knowledge of women in utilization of 25 plant species for curing various diseases. Chandra (2004) studied the variations in morphological parameters and energy exchange characteristics on five herbaceous medicinal crops from the alpines of Central Himalayas. All the species absorb higher amount of energy at lower altitudes, which indicates their adaptability to warm temperatures at low altitudes (up to 550 m). Chaurasia and Gurmet (2004) published a “Checklist of on medicinal and aromatic plants of trans Himalayan cold desert (Ladakh and Lahaul-Spiti).” Samal et al. (2004) represented linkage of indigenous healthcare practices with bioresources conservation and socio-economic development in central Himalayan regions and documented more than fifty indigenous healthcare practices. Kala et al. (2004) reported a total of 300 medicinal plant species used against curing of 114 ailments by the various ethnic and non-ethnic communities of Uttaranchal State. These 114 ailments were further grouped into 12 broad classes of diseases in order to project the indigenous uses of medicinal plants for various ailments. It was found that herbs contributed the highest number of medicinal plants (65%), followed by shrubs (19%) and trees (16%). The maximum number of plant species was used to cure generalized body aches and colic, followed by gastrointestinal and dermatological problems. Vitex negundo was the most important species, used for the treatment of more than 48 ailments. Azadirachta indica, Woodfordia fruticosa, Centella asiatica, Aegle marmelos, Cuscuta reflexa, Butea monosperma, Phyllanthus emblica, and Euphorbia hirta were among other important medicinal plants based on their high use values. The underground parts of the plant were used in the majority of cases. Of 300 medicinal plants, 35 were rare and endangered species, of which about 80% was restricted to the high altitude alpine region of Uttaranchal Himalaya. A priority list of 17 medicinal plant species was prepared on the basis of endemism, use value, mode of harvesting and rarity status. Srivastava and Chandrasekar (2004) studied ethnomedicine of Pin valley National Park, Himachal Pradesh and reported plants used in treating dysentery. Chandrasekar and Srivastava (2005) presented new reports on aphrodisiac plants from Pin valley National park, Himachal Pradesh. Kala (2005a) studied the current status of medicinal plants used by traditional Vaidyas in Uttaranchal of Central Himalayan region. A total of 243 herbal formulations prepared from 156 medicinal plants by Vaidyas for treating 73 different ailments were documented. Of these 55% were cultivated and 45% were wild species. Among the cultivated species 80% were grown in the kitchen gardens and 20% in the agricultural fields. Relatively a higher percentage of, i.e., 87% of kitchen garden species were used in 243 formulations. The 55% medicinal plants growing in the wild were also used in preparing herbal formulations. Kala (2005b) monitored the population density of threatened medicinal plant species in seven protected areas in the Indian Himalayas and also documented the indigenous uses of threatened medicinal plants through interviews with 138 herbal healers (83 Tibetan healers and 55 Ayurvedic healers) residing in the buffer zone villages of these protected areas. Twenty-two percent of threatened medicinal plant species were critically endangered, 16% were endangered, and 27% were vulnerable. Thirty-two threatened medicinal plant species were endemic to the Himalayan region. The density of threatened medicinal plant species varied with protected areas. Kala (2005c) published a report on health traditions of Buddhist community and role of Amchis in trans-Himalayan region of India.

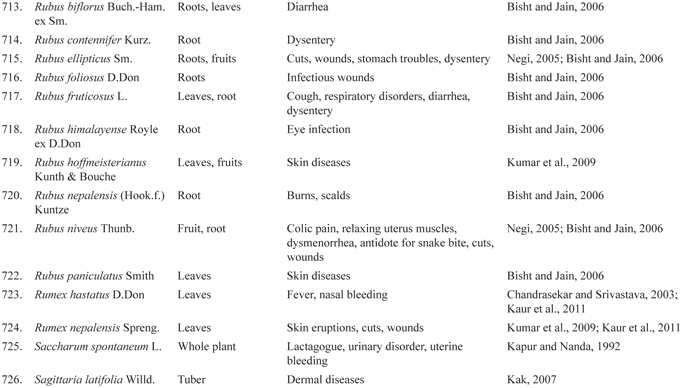

Negi (2005) studied socio-cultural and ethnobotanical value of a sacred forest, Thal Ke Dhar, Central Himalaya. Tyagi (2005) published a book on field guide for medicinal plants. The Valley of Flowers protected area had the highest number of threatened medicinal plant species. The local healers used these threatened species for curing about 45 different ailments. Traditional practice followed to cure pinworm and diarrheal problems among infants by using herbal materials along with their scientific validation was presented by Sharma and Maheshwari (2005). Ballabh and Chaurasia (2006) published a paper on Ethnobotanical studies on Boto ribe in Ladakh. Bisht and Jain (2006) reviewed ethnobotanical studies of genus Rubus (Rosaceae) from North-Western Himalayas. Kala (2006) recorded 335 medicinal plant species of the high altitude cold desert in India and their diversity, distribution and traditional uses were discussed. Of which 45 species were rare and endangered. The main part of the plant used in preparing remedy was the leaf, followed by the flower, root, shoot, seed and fruit. The distribution pattern of the medicinal plants was, generally, localized because most (27%) were restricted to marshy and moist areas, followed by dry scrub (13%), rocks (12%), boulders (10%) and undulating land or alpine meadows (9%). The maximum rare species were found in the Pin valley, followed by the Zanskar and Leh valleys. Kanwar et al. (2006) conducted a research work in six villages of Kangra district of Himachal Pradesh to study the home scale use in treating various ailments. A total of thirty-one medicinal plants used for the treatment of various ailments at home scale level by the villagers were reported. Twenty plant species were used for curing more than one disease. Three plants, Aloe barbadensis Mill., Asparagus racemosus Roxb. and Tinospora cordifolia Willd. were used against more than five diseases. The tendency of elder people was observed towards the use of herbal medicines in comparison to middle and young people.

Bhatt and Negi (2006) discussed ethnomedicinal plants of Jaunsari tribes of Garhwal Himalaya and found 66 plant species from 52 genera and 41 families were used for treatment of 64 different diseases. Out of 66 plant species 9 were tree species, 11 shrubs and 46 herb species. Various plant parts like roots of 31 plants, leaves and fruits of 23 plants, wood and bark of 9 plants and whole plants 18 species were used in preparation of remedies. The common diseases cured by the tribal community are tuberculosis, asthma, paralysis, diarrhea, jaundice, ophthalmic, kidney stone, bone fracture, mental disorder, arthritis, urinogenital disorders, snakebite, wounds and cuts, etc. Out of 66 plant species 13 fall in rare, 7 in endangered and 1 in vulnerable categories, however five species of plant kept under endangered and rare categories are common to this area. Helle and Olsen (2006) estimated that the trade of medicinal plants for herbal remedies is large and probably increasing. The trade has attracted the attention of scientists and development planners interested in the impact on plant populations and the potential to improve rural livelihoods through community based management and conservation. Pande et al. (2006) published a book on folk medicinal and aromatic plants of Uttaranchal which deals with 1338 ethnomedicinal plants and 364 ethnoveterinary plants followed by diversity of MAPs, MAPs available in Uttaranchal used in Indian System of Medicines (ISM), biologically active MAPs, rare and threatened MAPs, ethno-medico-zoological wisdom and alternative systems of therapies prevailing in Uttaranchal. Verma and Chauhan (2006) studied ethno-medico-botany of Kunihar forest division of district Solan (H. P.). Uniyal et al. (2006) enlighted traditional use of medicinal plants among the tribal communities of Chhota Bhangal, western Himalaya. A total of 35 plant species were used to cure various ailments, out of which 25 were herbs, 5 trees and 4 shrubs and one climber however, stem and flowers were reported as least used plant parts. Chaurasia et al. (2007) published a book entitled “Ethnobotany and Plants of Trans-Himalaya” which includes a total of 643 plant species belonging to 285 genera and 63 families. The major use of floral diversity is commonly for medicinal purposes (271) followed by (170) fodder, (96) edible, (45) ornamental, (42) fuel and (19) forest development, etc. Maximum plant species in the family Asteraceae (92), followed by Poaceae (61), Fabaceae (55), Brassicaceae (46), Caryophyllaceae (25), Lamiaceae (24), Polygonaceae (19), Boraginaceae (19), Apiaceae (18), Gentianaceae (14) respectively. Similarly the dominant genera are Astragalus (25 sp) followed by Artemisia (16 sp), Nepeta (13 sp), Polygonum (10 sp), Salix (10 sp), Allium (10 sp), Potentilla (9 sp), Poa (8 sp), Gentiana (7 sp), respectively. Samant et al. (2007) reported 643 medicinal plants belonging to 388 genera and 137 families used by the local communities of Himachal Pradesh in the north western Himalaya. The medicinal plants represents various life forms 106 trees, 121 shrubs and 416 herbs. Various plant parts viz. root, rhizomes and tubers (224 spp); whole plants (185 spp); leaves (164 spp); seeds (82 spp); fruits (81 spp); bark (72 spp); flowers (49 spp); stems (24 spp); latex (13 spp); resin (10 spp); aerial parts (8 spp); inflorescence (7 spp); fronds, gum, nuts, wood, oil and grains of (2 spp each); wax, cone and twigs of (1 species each) were used in preparation of remedies.

Ballabh et al. (2007) reported the development of herbal products from medicinal plants of Ladakh. Ballabh and Chaurasia (2007) presented 56 medicinal plants of Ladakh used against cold, cough and fever. Kak (2007) studied ethno-botany of macrophytes of North Western Himalayas. Ballabh et al. (2008a) highlighted the utility of 68 ethno-medicinal plants of cold desert Ladakh against kidney and urinary disorder. Ballabh et al. (2008b) studied traditional medicinal plant of cold desert Ladakh used in treatment of Jaundice. Chak et al. (2008) conducted an ethnomedicinal study of some important plants used in the treatment of hair and boils in district Pulwama of Kashmir. Lata et al. (2008) gave an overview of ethnobotanical studies on Uttarakhand state. Lal and Singh (2008) presented an indigenous herbal remedies used to cure skin disorders by the natives of Lahau-Spiti in Himachal Pradesh. Lata et al. (2008) gave an overview of ethnobotanical studies on Uttarakhand state in North India. Mahmud et al. (2008) studied ethno-medico-botany of some important aquatic plants of Jammu province (J&K). Ballabh and Chaurasia (2009) published a paper on medicinal plants of cold desert Ladakh used in treatment of stomach disorders. Chak et al. (2009) conducted an ethno-medicinal study of some important plants used in the treatment of hair and boils in district Pulwama of Kashmir. Kharkwal (2009) studied the diversity and distribution of medicinal plant species from the Indian central Himalaya and recorded 126 trees, 129 shrubs and 548 herbs between 200-5800 m a.s.l. The Fabaceae and Rutaceae were found to be the most dominant family in tree species; Verbenaceae and Fabaceae in shrub species whereas in case of herbs, Asteraceae was found to be the dominant family. The total number of species including all growth forms was maximum near low altitude to mid altitude and decreased consistently with increase in altitudes. Guleria and Vasishth (2009) studied ethnobotani- cal uses of wild medicinal plants by Guddi and Gujjar tribes of Himachal Pradesh. Pant et al. (2009) reported that 33 plant species are used traditionally to cure various diseases/ailments by the inhabitants surrounding Mornaula reserve forest in Western Himalaya. Bisht and Purohit (2010) discussed the medicinal and aromatic plant diversity of Asteraceae family in Uttarakhand. Gangwar et al. (2010) estimated ethnomedicinal plant diversity in Kumaun Himalaya and observed 102 species from 48 families are being used in folk-medicine system. He covered Almora, Champawat, Bageshwar and Pithoragarh. Pala et al. (2010) studied the traditional uses of 61 medicinal plants belonging to 28 families of Pauri Garhwal, Uttarakhand used by local communities for treating various ailments. Out of 61 medicinal plants 12 plants belong to Asteraceae, 9 plants each belong to Rosaceae and Lamiaceae, 3 plants belong to Pinaceae family and roots/rhizomes of 13 species, fruits/flowers of 7 species, seeds of 8 species/leaves of 10 species were used in preparation of various remedies. About 10 plant species were also used to cure certain diseases of cattle by the local communities. Pant and Samant (2010) carried out an ethnobotanical survey in the Mornaula reserve forest of Kumoun in western Himalaya and recorded 337 economically important species including medicine (221 species). Semwal et al. (2010) documented 60 species of medicinal plants used by the local vaidyas against treatment of 34 different ailments viz. headache, fever, cancer, female disorders and intestinal problems, etc. of Ukhimath block in Uttarakhand State. Out of 60 medicinal plants 45 herbs, 8 trees, 5 shrubs and 2 climbers were used in preparation of remedies from various plant parts such as roots and rhizomes (41.66%) followed by leaves (31.66%); fruits and seeds (15%). Samal et al. (2010) reported indigenous medicinal practices of Bhotia tribal community in Indian central Himalaya and documented 40 plants species used in preparation 50 indigenous medicines and treatment practices against 45 different kinds of ailments by the Bhotia tribes.

Ballabh and Chaurasia (2011) emphasize the medicinal use of 51 species of cold desert plants against gynecological disorders. Dad and Khan (2011) documented threatened medicinal plants of Gurez valley of Kashmir Himalayas their distribution pattern and conservation status. Badola and Aitken (2011) studied the Himalayan medicinal plant as a major source of raw material for various pharmaceutical companies, ethnomedicinal practitioners and exporters. 13 medicinal plant species used by people of Mandi district in Himachal Pradesh for treating different disease conditions was given by Kaur et al. (2011). Kala (2011) studied the floral diversity and distribution of 647 species of high altitude plants of cold desert Ladakh. Gupta (2011) submitted PhD thesis on Ethnobotanical studies of Gaddi tribe of Bharmor area of Himachal Pradesh. Kumar et al. (2011) reported that 57 species of plants are being used by the ethnic people of Garhwal Himalayas for medicine. Phondani et al. (2011) conducted a study on eth- nobotanical use of plants among Bhotiya tribes of Niti valley in Central Himalaya and discussed 86 medicinal plant species used for curing 37 common ailments by them. Kumari et al. (2011) describes the distribution and traditional uses of 188 medicinal plants belonging to 80 families in which 35 species were trees, 112 were herbs, 35 were shrubs and 6 were climbers. Various plant parts viz. 55 whole plant, 47 roots, 32 each of fruits and seeds, 41 leaves, 23 barks, 14 flowers, 11 stems, 2 inflorescence, 8 bulbs, 6 rhizomes, 3 latex and 5 oil were used in treatment of various ailments. Dangwal et al. (2011) presented ethno-medicinal information on 21 plant species belonging to 20 families of Nanda Devi biosphere reserve, Chamoli. The remedies are given as a single drug in the form of decoction, extract, oil, powder and pellets. These are prepared from leaves, petiole, bark, stem, roots, flowers, seeds, latex or entire plant. The common health problems are skin ailments, cuts, wounds, cold, cough, chronic fever, headache, stomachache, urinary complaints, respiratory disorders and gynecological disorders, etc. Bisht et al. (2011) reported anticancerous values of 24 plants. These include Acorus calamus, Aegle marmelos, Aloe vera, Andrographis paniculata, Asparagus racemosus, Betula utilis, Bidens bipinnata, Cassia fistula, Catharanthus roseus, Centella asiatica, Cleome viscosa, Curcuma domestica, Nelumbo nucifera, Ocimum tenuiflorum, Phyllanthus amarus, Piper longum, Plumbago zeylanica, Podophyllum hexandrum, Rubia cor- difolia, Taxus baccata, Terminalia arjuna, Tinospora cordifolia, Trigonella foenum-graecum and Withania somnifera. These plants are used for the treatment of various types of tumor/cancer such as sarcoma, lymphoma, carcinoma and leukemia. Most of them were effective in experimental as well as clinical cases of cancers. Kumar and Hamal (2011) studied herbal remedies used against arthritis in Kishtwar High Altitude National Park. Malik et al. (2011a, b) described the ethnomedicinal uses of 30 plants, belonging to 30 genera and 22 families and conservational aspects of medicinal plants in the Kashmir Himalaya. The medicine in different mode of preparation used to heal external burns, abrasions and wounds; orally taken to cure digestive, respiratory, skin and muscular disorders; and also used as diuretic, antipyretics, analgesic, anti-inflammatory, antiseptic, febrifuge, etc. Rana and Samant (2011) documented 270 medicinal plants belonging to 84 families and 197 genera from Manali wildlife sanctuary in north western Himalaya. Out of the total, 162 medicinal plants were native and 98 were endemic to the Himalayan region. Maximum species were used for stomach problems, followed by skin, eyes, blood and liver problems. Thirty-seven species were identified as threatened. Dactylorhiza hatagirea, Aconitum heterophyllum, Arnebia benthamii, Lilium polyphyllum, Swertia chirayita, Podophyllum hexandrum, Jurinella macrocephala, Taxus baccata subsp. wallichiana, etc. were highly preferred species and continuous extraction from the wild for trade has increased pressure which may cause extinction of these species in near future. Angmo et al. (2012) shown changing aspects of traditional healthcare system in Western Ladakh.

Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used by the people of Ganderabal district in Western Himalayas was carried out by Baba et al. (2012), Bhellum and Singh (2012) recorded 35 species of medicinal plants belonging to 32 genera and 22 families of district Samba of Jammu and Kashmir State. The promising species include Ageratum conyzoides L., Ajuga bracteata Benth., Barleria prionitis L., Centella asiatica L., Bauhinia purpurea L., Cuscuta reflexa Roxb. Woodfordia fruticosa Kurz, etc. Kala and Ratajc (2012) highlighted the ethnobotanical similarities of high altitude biodiversity of the Alps and the Himalaya. A total of 59 ethnobotanical species belonging to 17 families found common in both the Indian Himalayas and the Slovenian Alps. Of these 78% species were having medicinal properties and traditionally used for curing various ailments by the local people. In Indian Himalayas 73% people use the remedies which are comparatively higher than the people of Slovenia (42%). Out of the total medicinal plants, only 7 plant species such as Acorus calamus, Capsella bursa-pastoris, Hypericum perforatum, Origanum vulgare, Prunella vulgaris, Solanum nigrum and Urtica dioica had some common uses in both the places. In the Slovenian Alps, 61% had wide distribution range whereas in the Indian Himalayas 62% had localized distribution. Though 27% of common ethno-botanical species belonged to different threat categories, but only 2 species Taxus baccata and Hippophae rhamnoides - are placed under similar threat category in these two different mountain areas. Khan et al. (2012) presented ethnomedicinal plants used for toothache in Poonch district of Jammu and Kashmir (India). Kumar and Bhagat (2012) studied ethnomedicinal plants of district Kathua (J&K). Mahajan et al. (2012) made an inventory on ethnobo- tanical and medicinal plants of North Western Himalayas. Mala et al. (2012) surveyed ethno-medicinal plants of Kajinaag range of Kashmir Himalaya. Rashid (2012a, b) studied ethnomedicinal plants used in the traditional phytotherapy of chest diseases and rheumatism by the Gujjar-Bakerwal tribe of district Rajouri of Jammu & Kashmir state. Rokaya et al. (2012) studied the distribution patterns and trends of plant parts used among different groups of medicinal plants, geographical regions. Total number of medicinal plants as well as different groups showed unimodal relationship with elevation. Shah et al. (2012) conducted an ethnobotanical study of some medicinal plants from tehsil Budhal, district Rajouri (Jammu and Kashmir). Sharma et al. (2012) studied medicinal plants used for treatment of jaundice by the indigenous communities of the Sub-Himalayan region of Uttarakhand. A total of 40 medicinal plants belonging to 31 families and 38 genera were recorded. The local communities used the medicinal plants in 45 formulations as a remedy of jaundice. Bhoxa, nomadic Gujjars and Tharu communities used 15, 23 and 9 plants, respectively. Eight plants reported as new remedy of jaundice in India viz., Amaranthus spinosus L., Cissampelos pareira L., Ehretia laevis Roxb., Holarrhena pubescens Wall., Ocimum americanum L., Physalis divaricata D. Don, Solanum incanum L., and Trichosanthes cucumerina L. It is also reported that a total of 214 species from 181 genera and 78 families; 19 species from 18 genera and 12 families and 14 species from 14 genera and 11 families are used as internal, external and magico- religious remedies for jaundice, respectively by various communities in various parts of India. Most commonly used hepatoprotective plant species for treatment of jaundice in India is Boerhavia diffusa L. followed by Tinospora cordifolia (Willd.) Miers, Saccharum officinarum L., Phyllanthus amarus Schumach., & Thonn., Ricinus communis L., Andrographis panicu- lata (Burm. f.) Nees., Oroxylum indicum (L.) Kurz, Lawsonia inermis L., and Eclipta prostrata (L.) L. Tariq and Tantry (2012) conducted preliminary study on plants with anthelmintic properties in Kashmir. Yousuf et al. (2012) presented traditional plant based therapy among rural communities of some villages of Baramulla district (Jammu and Kashmir). Azad and Bhat (2013) recorded ethnomedicinal plants from Rajouri-Poonch districts of J&K state. Dangwal and Singh (2013) conducted an ethno-botanical study of some forest medicinal plants used by Gujjar tribe of district Rajouri (J&K), India. Gupta et al. (2013) conducted an ethno-botanical study of medicinal plants of Paddar valley of Jammu and Kashmir, India. Hassan et al. (2013) carried out an ethnobotanical study in Budgam district of Kashmir valley. Jeelani et al. (2013) studied some polypetalous plants of Kashmir Himalaya and recorded a total of 38 species belonging to 18 families of Polypetalae from various higher altitudes parts of Kashmir. Certain important ethnobotanical information about Alchemilla vulgaris, Ranunculus palmatifidus, Saxifraga siberica, Sedum wallichianum and Sedum heterodontum is reported for the first time from Kashmir Himalaya. Most of the species are used against general health problems and wound healings besides the treatment of diseases of skin, gastric, cough, etc. The roots are the frequently used plant parts followed by leaves, flowers, whole plant, seeds and others (bark/aerial parts), etc. Kumari et al. (2013) surveyed an ethnobotanical and medicinal plants used by Gujjar community of Trikuta Hills in Jammu and Kashmir, India.

Singh (2013) conducted an ethnobotanical survey among Lahaulas in Lahaul and Bhotias in Spiti valley of Himachal Pradesh of Indian western Himalaya and highlight 86 plant species belonging to 69 genera and 34 families are used to cure about 70 different ailments by the traditional healers. Maximum number of plant species used in herbal formulations belonged to families Asteraceae, Apiaceae, Gentianaceae, and Polygonaceae. Both single herbal preparations and polyherbal formulations are prescribed and administered by local healers known as Larje in Lahaul and Amchis in Spiti. Most of the remedies are prescribed in a powder form, some as juice and decoctions. Among plant parts, leaves were recorded to be used to a large extent as a remedy, followed by flowers. The maximum numbers of plants were used to cure stomach disorders, while the highest extent of phytotherapeutic use among all the species had Hippophae rhamnoides (17.14%). Rawat et al. (2013) described 76 ethnomedicinal plants belonging to 27 families and 56 genera of Sunderdhunga valley in Western Himalaya. Under the use value 13 species are used for cut and wounds, 8 for fever, 7 for cold, cough and stomach pain, 2 for insect sting, respiratory problems, muscle pain, toothache, joints pain, etc. Bhatt et al. (2013) documented indigenous uses of medicinal plants by Vanraji tribes of Kumaun Himalaya. A total of 48 common plants were used to treat various ailments, out of which 22 were herbs, 18 shrubs and 8 trees. A maximum of 30% leaves were used in preparation of remedies followed by 21% underground parts, 16% whole plants, 8% bark, flowers and inflorescence, 6% seeds, oil, resin and latex and 5% stems. The highest number of medicinal plants used in treatment of dermatological disorders (13 species 21%) followed by digestive disorders, generalized bodyache and reproductive disorders (6 species 10% each), musculoskeletal disorders (5 species 8%), antidotes to snake bite and scorpion sting, ophthalmic disorders, veneral and urinogenital disorders (4 species 7% each), respiratory problems (3 species 6%), dental, liver and gall bladder disorders (2 species 4%). The most prevalent ailments were skin disorders followed by digestive disorders such as diarrhea and dysentery. Mehta et al. (2013) conducted a study on herbal-based traditional practices of Bhotiya and Gangwals of Central Himalaya and recorded 78 plants species belonging to 39 families and 61 genera used in treatment of 68 different diseases.