Chapter 3

L2 Knowledge Is a Repertoire of Diverse Semiotic Resources

Overview

By and large studies of L2 learning have focused on learners’ development of conventional linguistic units such as vocabulary words and grammar or syntactic rules. However, we know that making meaning involves far more than words. Linguistic constructions are only one set of the many resources available to us in our activities for making and interpreting meaning. Nonverbal behaviors, for example, play a significant role in communication. We may point or gesture as we speak to indicate something or to emphasize a point. We also use eye gaze and facial expressions to communicate. Smiling when speaking or when listening to someone else speak can convey an affiliative stance toward the topic of the interaction or the persons with whom we are interacting. Technologies such as tablets, smart phones, and the internet have also broadened the scope of resources we use to interpret and make meaning. Images and graphic symbols such as pictographs and emojis have become common resources for representing a wide range of objects, places, people, emotions, and even ideas and concepts. All of the various means we use to communicate are called semiotic resources. In this chapter, we examine more closely the various semiotic resources that are available to us for making and interpreting meaning in our social worlds.

What Are Semiotic Resources?

As discussed in Chapter 2, our individual language knowledge is comprised of a wide range of linguistic constructions, stored in our minds as form-meaning pairings, that we develop and use in the myriad activities we engage in daily in our social worlds. It is not just with words, however, that we make meaning. In addition to language, we draw on a wide array of other means to make and interpret meaning in contexts of interaction. The term semiotic resources is used to refer to all of the various means of making meaning.

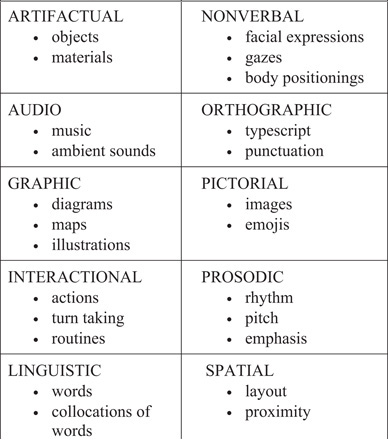

As shown in Figure 3.1, in addition to linguistic constructions, semiotic resources include prosodic conventions such as intonation, stress, tempo, pausing, and other features that accompany speech. Our semiotic resources also include nonverbal means of meaning making such as facial expressions, eye gaze, gesture, body positionings, and movement. For example, smiling, frowning, furrowing our brows, raising our hands, and pointing, either with speech or alone, can all perform different actions. In the case of writing, in addition to conventional linguistic constructions, semiotic resources include typescript, punctuation, and other typographic and orthographic conventions. Additional resources include graphic and pictorial modes such as diagrams, maps, and pictures, and artifactual modes such as objects, writing implements, and electronic devices. In fact, semiotic resources can be anything that is used with a communicative purpose.

Multimodality

Each type of semiotic resource is a socially made and culturally available mode for making meaning (Kress, 2014). A mode is a “regularised organised set of resources for meaning-making, including, image, gaze, gesture, movement, music, speech and sound-effect” (Jewitt & Kress, 2003, p. 1). The term multimodality refers to the multiplicity of modes in addition to speech and writing that individuals mobilize to make meaning. The term draws attention to the fact that human actions are built through the combination of many meaning-making modes at one time.

Figure 3.1 Examples of semiotic resources.

Spoken words, for example, are always accompanied by prosodic conventions such as intonation and stress. Varying these qualities can create different actions (Ochs, 1996). For example, varying the qualities of emphasis and intonation when uttering the word “hey” in English, changes the action being performed. Depending on how it is spoken, it can be a greeting, an attention getter, or even or an admonition. Moreover, spoken words are typically accompanied by particular arrangements of facial expressions, gestures such as head nods, and body movements. For example, to indicate a shared point of reference as we speak we may point with a finger or head tilt. Our words can also be accompanied by hand movements that, for example, hold an object such as a sign, or touch the screen of a smart pad.

Written text is also multimodal. Words in a text are rendered with particular visual dimensions such as font styles, sizes, and colors, and with particular page styles and spatial designs (Kress, 2010). The different assemblages or arrangements of resources serve different purposes. Depending on the visual and spatial arrangements of words on a page, the text might serve as an advertisement, a news headline, or an invitation. Depending on the material on which the words appear, e.g., a large outdoor board or a concrete wall, the text may be interpreted as a commercial sign or an expression of art.

The concept of a multimodal ensemble refers to the combination of modes in the making of meaning. It draws attention to the integration of a plurality of modes in the production and interpretation of actions (Goodwin, 2003; Jewitt, 2008; Kress, 2010; Mondada, 2016). The following two examples demonstrate how intertwined different modes are in performing actions. Consider a cooking show that airs on television. Observing what the chef is doing while she is speaking reveals how her actions are built through the juxtaposition of several modes. She may be holding a measuring cup in one hand, and, as she speaks, she may simultaneously pour what is in the cup into a bowl that she is touching with her other hand, moving her gaze between the camera and the bowl.

As another example, consider the synchronized use of multiple modes in addition to language that is entailed in teaching. Teachers must calibrate their language, facial expressions, gestures, body positions, and even the use of material artifacts such as a textbook or smart pad such that the pedagogical project is advanced, the shared attention of students is maintained, and individual student participation is promoted. Even allocating turns at talk occasions the synchronized use of eye gaze, head nods, and finger pointing (Kääntä, 2012; Mortensen, 2009).

These examples make clear that taking action, i.e., making meaning, involves complex ensembles of various semiotic modes, with language being but one of them (Early, Kendrick, & Potts, 2015; Goodwin, 2003; Kress, 2010). As Goodwin (2003, pp. 22–23) notes, “rather than being lodged in a single modality… many forms of human action are built through the juxtaposition of quite diverse materials, including the actor’s body, the bodies of others, language, structure in the environment, and so on”. In fact, in most cases, the actions that individuals build for each other in their social activities cannot be located in any single mode (Streeck, Goodwin, & LeBaron, 2011).

Meaning potentials

All semiotic resources, individually and in combination, have meaning potentials, i.e., conventionalized meanings that develop from their uses. Their conventionalized meanings represent the ways that groups and communities in the past have used the resources to accomplish particular goals that, in turn, are shaped by larger social institutions, e.g., the family, schools, communities, etc. and larger cultural and historical forces.

Meaning potentials of semiotic resources are not universal; they are context-sensitive with particular meanings activated or motivated by the contexts in which they appear. One implication of this is that the meaning of a resource in one context can be different when used in a different context. Take the English address term “ma’am”, for example. In some communities in the southern regions of the United States, it is considered a marker of politeness and respect and is used to by young people whenever they address their female elders. Not doing so is considered a sign of disrespect. In contrast, in communities in the northern regions of the United States, the use of ma’am for addressing adult women is considered by some to be old-fashioned, and even offensive to women. Using it to address a woman would be considered rude. In Quote 3.1, Mikhail Bakhtin, a renowned Russian philosopher of language, explains the historical relationship that exists between language and meaning.

Quote 3.1 The Relation Between Language Use and Meaning

There are no ‘neutral’ words and forms – words and forms that belong to ‘no one’; language has been completely taken over, shot through with intentions and actions. For any individual consciousness living in it, language is not an abstract system of normative forms but rather a concrete heterglot conception of the world. All words have the ‘taste of a profession, a genre, a tendency, a party, a particular work, a particular person, a generation, an age group, the day and hour. Each word tastes of the context and contexts in which it has lived its socially charged life; all words and forms are populated by intentions.

Bakhtin (1981, p. 293)

The meaning potentials of all semiotic resources are considered affordances in that in their local contexts of use, they offer particular visions of the world, that is, different possibilities for action, and different interpretive possibilities (Byrnes, 2006; Hall, 2011). For example, consider a greeting between two English speaking professionals, one a man and the other a woman. There is an array of conventional linguistic resources that they can choose for taking such actions, including “hi”, “hello, how are you”, “good day”, “hey, babe”, “wussup”, “yo”, and “what it be”, among many others. Each of these resources has a history of meaning that calls to mind particular contexts of use by particular individuals with particular communicative goals. Their use affords, i.e., makes possible, particular meanings and interpretations of experiences. The specific greeting the two professionals choose to use will construe their experience differently, from very informal to very formal and their relationship from close, perhaps even intimate friends, to neighbors, or to colleagues. Tomasello (1999, p. 8) provides another example on how the same object, event, or place can be construed differently by the use of different words depending individual communicative goals:

in different communicative situations one and the same object may be construed as a dog, an animal, a pet, or a pest; one and the same event may be construed as running, moving, fleeing, or surviving; one and the same place may be construed as the coast, the shore, the beach, or the sand – all depending on the communicative goals of the speaker.

Nonverbal behaviors likewise have different meaning potentials. The same resource can present different meanings depending on the context. For example, a raised hand can signal that one wants a turn to speak or to stop an action, or that someone is taking an oath in a courtroom prior to offering testimony. Conversely, similar actions can be enacted with different nonverbal resources. We can attempt to stop someone from doing something by a shake of the head, a raised hand with the palm facing outward, or by an extended gaze with furrowed brow, with choices for the type of resource used determined by the particular context of interaction and the communicative goal of the individual in that context.

Objects, too, have different meaning potentials. For example, maps represent particular characteristics and locations of places, making it possible for users to navigate from one place to another. Calendars order days into time periods making it possible for users to organize and remember events. Public road signs inform, warn, and redirect drivers and pedestrians as they travel from one place to another.

The term modal affordance refers to “the material and the cultural aspects of modes: what it is possible to express and represent easily with a mode” (Jewitt, 2013, p. 149). No one mode is considered essential to meaning making. Rather, each contributes to the construction of meaning in different ways. To state another way, each semiotic mode offers particular possibilities for expression and representation. For example, the production of speech relies on articulators such as the tongue, lips, and other speech organs. Articulated constructions are produced in real time; each follows another, in sequential order. These are some of the affordances of the mode of speech. It is impossible, however, to verbally produce more than one construction at a time. This is one of the constraints of speech.

The affordances of images differ from speech in at least two ways. First, individuals rely on graphic or photo design tools rather than on speech articulators to produce meaning and second, since meaning is represented spatially, they afford the simultaneous representation of different meanings. For instance, viewing an image of a group of people, each engaged in a different activity, affords different understandings of the meanings enacted in the image than does listening to or reading a narrative describing the image.

Even spatial arrangements of objects such as tables and chairs afford different meaning-making potentials. In learning spaces like classrooms, for example, desks and chairs are key resources. Figure 3.2 displays some of the many ways that classroom spaces can be configured. Each possibility offers, i.e., affords, different types of instructional activities, different interactions between teachers and students, different opportunities for access to materials such as electronic devices and so on.

The pictures in Figure 3.2 display different classroom seating arrangements. In picture (a), we see that the desks are arranged in groups of three or four. This arrangement makes possible small group work and allows the teacher to freely circulate among the groups and interact with individuals and groups of students. In addition, the desks are not affixed to the floor, which allows them to be reconfigured by the teacher and students to make possible other kinds of learning activities. Picture (b) is quite different. It depicts a hall with theater seating, the arrangement of which readily affords teacher-fronted lessons such as lectures or demonstrations. However, while the arrangement of the seats allows students full visual access to the instructor, it limits the kind of instructional activities that can occur. It also limits the amount and type of interaction that can occur between the instructor and students and movement of the instructor among the students.

Figure 3.2 Semiotic resources of classrooms.

In picture (c), we can see that while the space is smaller than that in picture two, the arrangement of desks and chairs is somewhat similar in that the desks are in rows, facing the front of the room. This arrangement allows for teacher-fronted lessons and affords students visual access to the teacher but it constrains the teacher’s access to individual students and the types of learning activities that can occur. In picture (d), we can see that seating is organized quite differently. There are several tables in the room on which sit computers and for each computer there is a chair. Such an arrangement easily affords individual instruction, facilitated by the electronic device each student faces. In all cases, there is no seating arrangement that is better than another. Rather, each affords particular teaching and learning opportunities.

As noted previously, the affordances of our semiotic resources develop from their past uses. Their histories of use become their “provenance, shaping available designs and uses” (Jewitt, 2008, p. 247). While the resources’ conventionalized meanings bind individuals to some degree to particular ways of making meaning with them, how they come to mean at a particular communicative moment, i.e., the personalized meaning potentials that individuals are able to create, is always open to negotiation (Mattiessen, 2009). In their uses of their resources at a particular moment in a particular context, individuals choose “a particular way of entering the world and a particular way of sustaining relationships with others” (Duranti, 1997, p. 46). The term design was coined by the New London Group (1996, 2000) to capture the dynamic processes by which individuals make meaning with their available resources. To design is to create meanings through the organization of semiotic resources in ways to achieve one’s communicative purposes (Cope & Kalantzis, 2009; Kress, 2010, 2014).

Communicative Repertoires

The term repertoire was introduced in Chapter 2 to refer to the totality of linguistic constructions that we develop in our life experiences. Here, we expand the term to include all of the meaning-making resources that we use to participate in the multiple communities to which we belong (Rymes, 2010). The term communicative emphasizes not only the functional nature of the resources comprising our repertoires but their diversity as well.

The resources comprising our repertoires do not exist in random relation to each other. Rather, they are linked to registers and schemas of expectations for their use. Registers comprise sets of semiotic resources that, in their use, are associated with particular activities, particular institutional contexts, and with particular people who engage in such activities and contexts (Agha, 2004). They can vary in terms of degree of formality of resources used to make meaning. For example, we have registers that are associated with school, home, commercial businesses, and professions such as medicine, the law, and teaching. Registers are also associated with particular social roles, such as parents, teachers, students, doctors, lawyers, judges, and so on. Schemas of expectations are ethnographically-grounded understandings, “sedimented social knowledge” (Hanks, 1996, p. 238) that individuals have about the contexts to which their resources and registers are connected and how they function in their social works (Levinson, 2006).

Box 3.1 is an example of how schemas of expectations of resource meanings are exploited to humorous effect. This was found on a sign outside of a church located in the southern region of the United States. For many social groups, the English utterance “Don’t make me come down there” evokes the social roles of parents and children, and a typical situation in which one or some children are misbehaving.

Box 3.1 On a sign outside of a church

Don’t make me have to come down there

—God

Stated by the parent, the utterance serves to reprimand the children for their behavior. While the consequences for ignoring the warning are not stated, it is implied that they will be dire if the actions do not stop. Attributing the utterance to God, believed by many to be the supreme protector of all humanity, suggests a similar context of use. In this case, the utterance ascribes to God the role of reproaching parent to a world filled with badly behaved children.

As the paths that our life experiences take are not linear, neither do the registers comprising our communicative repertoires develop along a straight path of ever-increasing size. Rather, they arise from a “wide variety of trajectories, tactics and technologies, ranging from fully formal language learning to entirely informal ‘encounters’ with language” (Blommaert & Backus, 2012, p. 1). As we meet new people, take on new goals, enter into new activities or new institutions or move to new communities, some of our resources may become more entrenched or well-established, others may change, others forgotten and still others may simply disappear.

Super-Diverse Communicative Repertoires

The world is ever more complex. Large scale migration within and across regions, nations, and continents continues to bring people from around the world together in groups, communities, schools, workplaces, places of worship, and other social institutions. People come with highly varied nationalities, ethnicities, languages, and life experiences and as a result of widely varying motives for moving that range from conflict, war and famine, to educational advancement, economic aspirations, and global business.

Adding to the complexity is the continued advancement of information technologies and social networking sites that bring people from diverse geographical locations around the world together to exchange information, share interests, and develop, maintain, and extend social relationships. Together, these forces have not only afforded the wide and rapid circulation of semiotic resources across individuals, groups, and communities, but they have also given rise to new, complex, multilingual, and multimodal semiotic resources (Rymes, 2012; Blommaert, 2013). Blommaert (2012, p. 13) explains, “in superdiverse environments (both on- and offline), people appear to take any linguistic and communicative resource available to them … and blend them into hugely complex linguistic and semiotic forms”. The value of the term communicative repertoire in capturing the impact of these super-diverse forces on individuals’ semiotic resources is this:

Repertoires enable us to document in great detail the trajectories followed by people throughout their lives: the opportunities, constraints and inequalities they were facing, the learning environments they had access to (and those they did not have access to), their movement across physical and social space, their potential for voice in particular social arenas.

(Blommaert & Backus, 2011, p. 24)

Summary

The resources at our disposal for making meaning involve more than just language. They include complex ensembles of various semiotic modes for making and interpreting meaning. The histories of meanings attached to our semiotic resources afford us particular ways of construing our worlds. We use them to design meanings in particular contexts of use to achieve our communicative purposes. The many meaning-making resources we use to participate in our social worlds comprise our communicative repertoires. Our repertoires are not locked, impermeable to change, but are massively dynamic, responsive to conditions at all levels of social activity. As our life experiences in our social worlds change, so do the resources comprising our repertoires. All else being equal, the greater the diversity of experiences we have, linguistically and otherwise, the more diverse our repertories are.

Implications for Understanding L2 Teaching

Language is at the heart of language teaching. Understanding what language is affects how we teach. Three implications for understanding L2 teaching can be derived from an understanding of language knowledge as repertoires of diverse semiotic resources.

Understanding language knowledge as repertoires of diverse semiotic resources changes how we understand the activity of teaching. Making and interpreting meaning in contexts of action involve not just linguistic constructions, but a plurality of modes. This is the case for teaching and learning, in fact, for any kind of social activity. Imagine reducing the activity of teaching to just one mode. It is impossible. We cannot speak without using prosodic cues such as stress and rhythm. We cannot write without choosing a writing system and deciding whether to type or write by hand. We cannot teach without deciding on a type of spatial arrangement. Contributing to the work of teaching are artifacts, often used simultaneously with talk, and gestures and other body movements that serve to secure and maintain learners’ attention as we speak. It is a fact that teaching cannot be accomplished without utilizing a number of multimodal ensembles. Focusing attention on only one mode renders invisible the complex and specialized multimodal work of teaching.

Understanding language knowledge as repertoires of diverse semiotic resources also changes how we understand the objects of L2 learning. Learning another language is about much more than just learning language, e.g., conventionally prescribed grammar rules. Privileging language as the central, only means of full expression and representation is inadequate for meeting the challenges of living in contemporary times. Rather than constraining learners’ choices for meaning making, we need to expand opportunities for learners to adopt new resources and new ways of using already familiar resources so that their multilingual and multimodal options enable them to bring their social worlds into existence, maintain them, and transform them for their own purposes. The what they learn is conceived not only as structures of resources. Rather, it is also, and more importantly, conceived as ways of designing. L2 learning then is about learning how to choose from the vast range of available resources to (re)create learners’ potential in ways that project their “interest into their world with the intent of effect in the future” (Kress, 2010, p. 23).

Our learners live in an ever-changing world. Every day they come into contact with new people, new contexts of action, and new meaning-making resources. Their meaning-making skills reach far beyond what we can imagine. Rather than treating their skills and knowledge as peripheral to the work we do in our classrooms, we must embrace them, that is, “recruit … the different subjectivities, interests, intentions, commitments and purposes that students bring to learning” (The New London Group, 2000, p.18), and use them to inform our classroom practices.

Pedagogical Activities

The activities in this section, organized around the four types of knowledge processes, will assist you in relating to and making sense of the concepts that inform our understanding that L2 knowledge comprises repertoires of diverse semiotic resources.

Experiencing

A. Semiotic Resources

Watch this commercial from Sheraton Hotels and Resorts in which the narrator states: “The greetings are different, the need to feel welcome is the same. You don’t just stay here, you belong.”

www.youtube.com/watch?v=03WjUebwc2s

After watching the commercial a few times, consider the following:

What are two different types of greetings shown in the video and what semiotic resources are used in each?

How similar or different are they in terms of the semiotic resources that are used?

How similar or different are they to the various ways in which people from your social group(s) greet one another?

What implications can you draw from your findings for L2 teaching?

B. Semiotic Resources

Take or find two or three photos of different types of classrooms and address the following questions individually or in small groups.

What semiotic resources are in each of the rooms?

What are the meaning potentials of each resource?

What kinds of experiences have you had in each type?

How do you think the resources and spatial arrangements that you are familiar with have influenced the ways you learn? The ways you have taught or will teach?

What conclusions can you draw about how the designs of learning environments shape L2 teaching and learning?

Conceptualizing

A. Concept Development

Select two of the concepts listed in Box 3.2. Craft a definition of each of the two concepts in your own words. Create one or two concrete examples of the concept that you have either experienced first-hand or can imagine. Pose one or two questions that you still have about the concept and develop a way to gather more information.

Box 3.2 Concepts: L2 knowledge is a repertoire of diverse semiotic resources

design

communicative repertoire

meaning potentials

modal affordance

mode

multimodality

multimodal ensemble

semiotic resource

B. Communicative Repertoires

Read the quote by Christian Matthiessen and restate in your own words. Design a multimodal text that captures the substance of your understanding. The text can be paper (e.g., written text such as a personal narrative or poster that incorporates images or graphics) or digital (e.g., a video or slide presentation that incorporates written and/or spoken language, images, sound). Together with your class, decide on how to make your work publically available to others.

When people learn languages, they build up their own personalized meaning potentials as part of the collective meaning potential that constitutes the language, and they build up these personal potentials by gradually expanding their own registerial repertoires—their own shares in the collective meaning potential. As they expand their own registerial repertoires, they can take on roles in a growing range of contexts, becoming semiotically more empowered and versatile.

(2009, p. 223)

Analyzing

A. Meaning Potentials

Explore the positive lexicography project, developed by Tim Lomas, a lecturer at the University of East London. The project is an evolving index of “‘untranslatable’ words related to wellbeing from across the world’s languages”. According to its developer, the project aims to highlight different constructions by which cultures express well-being.

You can find the project at this site: www.drtimlomas.com/lexicography.

On the home page, click on the link Interactive lexicography and choose a theme to explore. Explain the findings from your explorations in terms of the meaning potentials and then consider the following question:

What implications for understanding the concept of meaning potentials can you derive from this project and from your explorations?

B. Multimodality

Head to this site on multimodality and learning: http://inclusiveclass rooms.org/practice/multimodality

The site is part of the Teachers College Inclusive Classroom Project (TCICP), which supports the development of educational practices that focus on inclusion in their classrooms. At the site, choose one or two of the projects to explore. In your explorations, take note of how multimodal resources are integrated into the projects and how useful the teachers found the projects to be to their own learning. Finally, consider the following question:

What implications about the value of multimodality can you derive for your own learning and for your L2 teaching context?

Applying

A. Multimodality

Using what you learned from your explorations at the TCICP site on multimodality, individually or collaboratively, create a digital multimodal story. The topic should be broadly related to L2 teaching and learning. There are many resources on the internet to help you. Type digital storytelling into an internet browser to locate them. Once completed, decide with your classmates on ways to disseminate your stories to a wider audience.

B. Multimodality

Using what you learned from the experience of creating your own story, individually or collaboratively, design a lesson on digital storytelling for a specific group of L2 learners. Before you begin, gather ideas from others. One easy way to do this is to type digital storytelling for L2 learners in an internet browser. Share what you find with your classmates and, together, decide on a set of components to include in the lesson. Once your lesson is completed, present it to your classmates. If possible, share lessons by uploading them to a public folder on the network.

References

Agha, A. (2004). Registers of language. In A. Duranti (Ed.), A companion to linguistic anthropology (pp. 23–45). Oxford: Blackwell.

Bakhtin, M. M. (1981). The dialogic imagination (Ed. M. Holquist). Austin: University of Texas Press.

Blommaert, J. (2012). Chronicles of complexity: Ethnography, superdiversity, and linguistic landscapes. Tilburg Papers in Culture Studies, 29, 1–149.

Blommaert, J. (2013). Citizenship, language, and superdiversity: Towards complexity. Journal of Language, Identity, and Education, 12, 193–196.

Blommaert, J., & Backus, A. (2012). Superdiverse repertoires and the individual. In I. de Saint-Georges and J. Weber (Eds.), Multilingualism and multimodality: Current challenges for educational studies (pp. 11–32). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Blommaert, J., & Backus, A. (2013). Repertoires revisited: Knowing language in superdiversity. Working Papers in Urban Language & Literacies, 67.

Byrnes, H. (2006). Perspectives. Interrogating communicative competence as a framework for collegiate foreign language study. The Modern Language Journal, 90, 244–246.

Cope, B., & Kalantzis, M. (2009). “Multiliteracies”: New literacies, new learning. Pedagogies, 4(3), 164–195.

Duranti, A. (1997). Linguistic anthropology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Early, M., Kendrick, M., & Potts, D. (2015). Multimodality: Out from the margins of English language teaching. TESOL Quarterly, 49(3), 447–460.

Goodwin, C. (2003). The body in action. In J. Coupland & R. Gwyn (Eds.), Discourse, the body, and identity (pp. 19–42). London: Palgrave-MacMillan.

Hall, J.K. (2011). Teaching and researching language and culture, 2nd ed. London: Pearson.

Hanks, W. F. (1996). Language & communicative practices. Colorado: Westview Press.

Jewitt, C. (2008). Multimodality and literacy in school classrooms. Review of Research in Education, 32(1), 241–267.

Jewitt, C. (2013). Learning and communication in digital multimodal landscapes. London: Institute of Education Press.

Jewitt, C., & Kress, G. (Eds.) (2003). Multimodal literacy. New York: Peter Lang.

Kääntä, L. (2012). Teachers’ embodied allocations in instructional interaction. Classroom Discourse, 3(2), 166–186.

Kress, G. (2010). Multimodality: A social semiotic approach to contemporary communication. London: Routledge.

Kress, G. (2014). The rhetorical work of shaping the semiotic world. In A. Archer & D. Newfield (Eds.), Multimodal approaches to research and pedagogy: Recognition, resources, and access (pp. 131–152). New York: Routledge.

Levinson, S. (2006). Cognition at the heart of human interaction. Discourse Studies, 8, 85–91.

Matthiessen, C. M. (2009). Meaning in the making: Meaning potential emerging from acts of meaning. Language Learning, 59(1), 206–229.

Mondada, L. (2016). Challenges of multimodality: Language and the body in social interaction. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 20(3), 336–366.

Mortensen, K. (2009). Establishing recipiency in pre-beginning position in the second language classroom. Discourse Processes, 46(5), 491–515.

New London Group. (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66, 60–92.

New London Group. (2000). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. In B. Cope & M. M. Kalantzis (Eds.), Multiliteracies: Literacy learning and design of social futures (pp. 9–37). London: Routledge.

Ochs, E. (1996). Linguistic resources for socializing humanity. In J. Gumperz & S. Levinson (Eds.), Rethinking linguistic relativity (pp. 407–437). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rymes, B. (2010). Classroom discourse analysis: A focus on communicative repertoires. In N. Hornberger & S. McKay (Eds.), Sociolinguistics and language education (pp. 528–546). Tonawanda, NY: Multilingual Matters.

Rymes, B. (2012). Recontextualizing YouTube: From micro-macro to mass-mediated communicative repertoires. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 43(2), 214–227.

Streeck, J., Goodwin, C., & LeBaron, C. (Eds.). (2011). Embodied interaction: Language and body in the material world. Cambridge University Press: New York.

Tomasello, M. (1999). The cultural origins of human cognition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.