Chapter 6

L2 Learning Is Mediated by Learners’ Social Identities

Overview

At the meso level of social activity are the sociocultural institutions within which contexts of interaction are situated. These institutions include the family, neighborhoods, schools, and places of work and worship. Also included are social and community organizations such as clubs, sports leagues, political parties, various online contexts, and so on. When L2 learners participate in particular social contexts of action of their social institutions, they do so as actors with specific constellations of historically laden, context-sensitive, and locally (re)produced social identities. In this chapter, we discuss the role that learners’ identities play in mediating the development of L2 learners’ repertoires of semiotic resources.

Social Identity

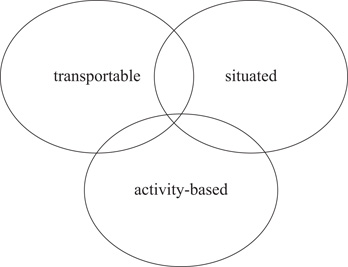

When we use our semiotic resources, we do so as individuals with multiple, dynamic, social identities. One facet of our identities is defined by macro-level demographic categories that are linked to the social groups into which we are born. These categories include social class, gender, race, ethnicity, religion, nationality, mother tongue(s), and generation. These have been referred to as transportable identities as, for the most part, these identities stay with us as we move across situations (Zimmerman, 1998).

For example, we are all born into families of particular socio-economic classes such as poor, working class, middle class, or prosperous and our memberships in these classes become part of our identities. Likewise, we are born into families who speak particular languages and thus take on identities as speakers of English, Chinese, Arabic, and so on. The geographical region in which we are born also provides us with particular group memberships and upon our birth we assume specific identities associated with nations and continents. We become identified as Canadian, British, African, South East Asian, and so on. Within national boundaries, we are defined by membership in regional groups, and we take on identities such as northerners, mid-westerners, or southerners and as city people, suburbanites, or rural residents. Finally, even the time period or generation into which we are born provides us with a particular identity. We become identified as Baby Boomers, Generation X-ers, Millennials, and so on.

A second dimension of our social identities is defined by the social roles and role relationships that are ascribed to us through our involvement in the various activities of the social institutions, such as school, church, family, and the workplace, comprising our communities. These institutions give shape to the kinds of social groups to which we have access and to the role-relationships we can establish with others. These have been referred to as situated identities (Zimmerman, 1998) and role-relational identities (Gee, 2017). For example, in schools, we take on roles such as teachers, students, or members of the administrative staff and in these roles, we assume particular relationships with others, such as student-teacher, student-student, teacher-teacher, teacher-administrative staff, and so on. Likewise, in our workplace, we assume roles as supervisors, managers, colleagues, or subordinates.

Another component of our situated identities is defined by the activities in which we are involved. Gee (2017) refers to these as activity- based identities. These are freely chosen identities, are wide ranging and include, for example, gamers, birders, carpenters, writers, gardeners, social activists, sports fans, and so on. Gee explains,

Activity-based identities are another form of collective intelligence, perhaps the most important form in today’s world. When someone takes on – as master, adept or lay person – an activity-based identity, they are networked to the values, norms, practices, and shared knowledge and skills – as well as the smart tools and other resources – of a large group of people who, through time and space, develop and continually transform effective ways to do certain things and solve certain sorts of problems.

(p. 85)

The ways we use our semiotic resources to enact our social identities are not based solely on personal intentions. Rather, our identities embody particular histories of expectations that have been developed over time by other group members enacting similar roles in the various contexts of action of their social institutions. These include expectations about particular registers for enacting our identities, beliefs, and attitudes about the kinds of groups to which we have access and the role-relationships we can establish with others.

Our social identities, then, afford us access to particular activities and to particular role-defined relationships with others. For example, depending on where a person is born, the opportunities for group identification including access to particular activities and resources, will vary depending on a person’s gender, race, social class, and so on. Opportunities for a white male born into a working-class family in a rural area in the northwest region of the United States, for example, will differ from those of a white male born into an upper-class family in the same area.

Our role relational identities are intimately linked to our transportable identities in that the expectations we hold about ours and others’ roles and role relationships are tied to ours and others’ transportable identities. For example, we tend to associate certain roles with particular transportable identities. In some groups, women are more often associated with care-giving roles such as teacher, nurse, and social worker, while men are usually associated with administrative roles such as executive, manager, and school principal. Associating transportable identities with particular roles can make it difficult for us to perform roles that are not conventionally linked to our identities. In some groups, a female taking on the role of chief executive in a business may experience difficulties in performing satisfactorily if the role is conventionally associated with males (Tracy & Robles, 2013).

We approach our activities with the expectations we have come to associate with ours and others’ social identities, and we use them to make sense of each other’s involvement in our encounters. Our expectations about what we can and cannot do as members of our various social groups are built up over time through socialization into our own social groups. The semiotic resources we use to communicate, and our interpretations of those used by others, are shaped by these mutually held expectations. Richard Bauman explains the inextricable link between social identity and semiotic resources in Quote 6.1.

Quote 6.1 Social Identity and Semiotic Resources

[Social identity] is the situated outcome of a rhetorical and interpretive process in which interactants make situationally motivated selections from socially constituted repertoires of identificational and affiliational resources and craft these semiotic resources into identity claims for presentation to others.

Bauman (2000, p. 1)

Our identities are not fixed or static but are fluid and “multifaceted in complex and contradictory ways” (Miller, 2000, p. 72) and reflective of the landscapes of our lived experiences (Wenger, 2010). Moreover, we never enact just one identity at a time. Rather, we have a nexus of memberships, which are in complex relation to each other, and constantly shifting and evolving across time and space (Douglas Fir Group, 2016; Ochs, 1993). In every act of meaning making, one or more of our social identities are “inferred and interactionally achieved” (Ochs, 1993, p. 291) through the simultaneous deployment of multiple semiotic resources, such as words, prosodic cues, gestures, facial expressions, and other resources that are associated with specific social groups (Bucholtz & Hall, 2005).

As mentioned previously, how we enact our identities depends on our expectations about our own identities and those of others. However, while our expectations influence our actions, they do not determine them. At any moment, there exists the possibility of taking up a unique stance towards our own identity and those of others, and of using our semiotic resources in unexpected ways towards unexpected goals (Hall, 2011; Norton & McKinney, 2011; Toohey, Day, & Manyak, 2007).

Social Identity and L2 Learning

The study of the mediating role that L2 learners’ social identities play in learners’ success in negotiating their access to and participation in various L2 social activities and groups has been the concern of a growing body of research in SLA. One early influential study is that by Bonny Norton (Norton, 2000; Pierce, 1995). Drawing on poststructuralist theory, and in particular the work of Weedon (1997) and Bourdieu (1991), Norton examined how the identities of a group of women who had migrated to Canada from different regions of the world were differentially constructed in their interactions with others in and out of the classroom. She argues that these different constructions had a significant influence on the women’s interest in language learning, making some more willing than others to invest the time and effort needed to learn English.

Norton’s study set off a ground swell of interest in the study of various types of identity and language learning. Some have examined how learners’ identities as learners are constructed (e.g., Cekaite & Evaldsson, 2008; Dagenais, Day, & Toohey, 2006; Song, 2010; Toohey, 2000). The study by McKay and Wong (1996), for example, examines how four Mandarin-speaking adolescents attempted to negotiate the shaping of their identities as English language learners and users in the contexts of their schools, and the consequences of their attempts relative to the development of their academic skills in English. Additional studies have similarly focused on how L2 learners negotiate their identities as learners and users of the L2. For example, the study by Daganeis, Day, and Toohey (2006), reveal how differences in literacy practices to which a multilingual child was given access in her French immersion classroom mediated teacher expectations of her future educational progress as an English language learner. Two of her teachers saw her as a capable learner while another teacher constructed her as a weak learner whose English skills needed remediation.

Also examined has been the role that learners’ gender identities play in mediating L2 learners’ learning trajectories (e.g., Hruska, 2004; Menard-Warwick, 2009; Morita, 2009; Skilton-Sylvester, 2002). For example, in her longitudinal study of four Cambodian women studying English in an adult community center in the United States, Skilton-Sylvester (2002) found that the ways that the women’s identities as spouses, mothers, sisters, daughters, and workers were addressed in the class influenced their participation. For two women, their roles as wives directly impacted their participation in their ESL program. One’s identity as an English learner was supported by her husband and she progressed quickly in the class. Another student’s identity was perceived as a threat to her husband, leading her to stop attending classes because she was “unable to maintain her identity as a student alongside her identity as a wife” (ibid, p. 17). Morita’s (2009) study showed how a male student could also feel alienated from learning opportunities. In this case, the individual was a PhD student in a Canadian university who felt marginalized because his theoretical perspective did not align with the disciplinary discourse of his academic department where feminism and critical theories were popular perspectives.

It is not the case that one’s gender identity only constrains L2 learning. As Miller and Kubota (2013) point out, enhanced and empowered gender identities can be associated with learning a language. This is exemplified in Pavlenko’s (2001) study of L2 learners’ memoirs, in which she found that for some female writers, the process of learning another language was perceived positively as a “reinvention of self through friendship and as connectedness with others” (p. 229).

Relationships between learners’ racial identities and L2 learning have also been explored by scholars (Ibrahim, 1999; Lin et al., 2004; Curtis & Romney, 2006; McKinney, 2007; Kubota & Lin, 2009; Shin, 2012, 2015). One early study by Ibrahim (1999) investigated how race impacted the L2 learning opportunities of immigrant African students in a Canadian high school. Ibrahim found that the students appropriated a nonmainstream language, African American English, as their L2 and in so doing created a particular identity of being black that was familiar to and respected by their peers. Shin (2012) examined how race and ethnicity intersected in the emergence of a new identity for Korean students in Canada. These students were what Shin labeled “yuhaksaeng”, i.e., Korean nationals with student visas. She found that, despite investing heavily in learning English, their investment did not succeed as in their local community of English speakers they were ascribed identities not as global cosmopolitans, but as fresh-off-the-boat Korean immigrants. To resist this racial marginalization, the students claimed a new identity that was “simultaneously global and Korean” (p. 185). They did so by mobilizing varieties of their Korean language and culture to construct themselves as “wealthy, modern, and cosmopolitan ‘Cools’ vis-á-vis both long-term immigrants in local Korean diasporic communities and ‘[White] Canadians’” (ibid.).

More recently, Darvin and Norton (2014) have argued for the need to include social class as a mediating factor of L2 learners’ opportunities for learning, claiming that social class differences in transnational contexts can impact L2 learners’ social and educational trajectories. They support their claim with a case study investigating the different opportunities to learn English afforded to adolescent migrant students residing in Canada. Both students came from the same country but their paths to Canada differed. One student, Ayrton, came from a well-to-do family that immigrated to Canada through a program designed to attract business people with substantial financial capital. In Canada, he attended a private school. The other student, John, came from a working-class family. His mother had been working in Canada for six years as a caregiver and John immigrated through a program that allowed his mother to apply for permanent residency for him in Canada. In his new community, John attended an inner-city public school. These class differences afforded Ayrton and John different opportunities to increase their economic, cultural, and social capital as immigrants in Canada. Ayrton was able to build greater capital while John’s opportunities remained limited. Darvin and Norton conclude that studies of identity and L2 learning must include social class as a significant variable in understanding the varied educational and social trajectories of L2 learners.

Another aspect of L2 learners’ social identities that shapes their L2 learning opportunities is their imagined identity as part of memberships in imagined communities (Kanno & Norton, 2003; Norton & Toohey, 2011; Pavlenko & Norton, 2007). Imagined communities are “groups of people, not immediately tangible and accessible, with whom we connect through the power of the imagination” (Kanno & Norton, 2003, p. 241). L2 learners desire to become members of imagined communities because they perceive that the communities can offer them opportunities to expand their range of identities and to increase their access to social, educational, and financial resources. L2 learners’ imagined identities in their imagined communities can push them to seek out and pursue L2 learning opportunities that might not otherwise be available to them. Such was the case, for example, for a group of immigrant parents of diverse language origins residing in Canada. This group of parents chose to enroll their children in French immersion programs so that they would be better equipped to take on identities as English–French bilinguals and thereby have access to economically more powerful contexts of interaction within their desired social institutions (Dagenais, 2003).

It is not always the case that real communities meet the expectations of learners’ imagined communities and identities. This was the case for a Japanese teenager, as reported by Kanno and Norton (2003). Although the student spent two thirds of his life in the English-speaking countries of Australia and Canada, he held firmly to his identity as Japanese and made every effort to maintain his Japanese language. However, upon his return to Japan, he found that his imagined community bore little resemblance to the “real” Japan, a discovery which led to his rejection of his Japanese identity. Differences between real and imagined communities can be even more consequential to L2 learners if access to their imagined communities is blocked or marginalized by the very people with whom they aspire to interact (Norton, 2001). This can lead to withdrawal from the community, and loss of desire to continue to learn the language of the community.

Digital Communication and Changing Identities

The expansion of digital technologies and social networking sites has created new transnational, online social spaces, which have become increasingly important arenas for the development and display of multiple activity-based identities, such as bloggers, gamers, web designers, fanfiction writers, and readers (Chen, 2013; Darvin, 2016; Duff, 2015; Lam, 2004, 2009; Thorne & Black, 2011; Thorne, Suaro, & Smith, 2015). These spaces and identities afford L2 learners multiple and varied opportunities to connect with others who share these interests.

Thorne and Black’s (2011) case study of an English language learner’s participation in an online fan fiction site illustrates this point. In their study, they show how joining a fanfiction site afforded Nanako, an English language learner from China and residing in a large city in Canada, opportunities to transform her identity as a writer. When Nanako first joined the site, in her representations of self to others, she positioned herself as inexperienced, not just with English, but as a writer of fan fiction as well. Over time, two dynamics led to a repositioning of her identity. One dynamic was the extensive opportunities to interact with a diverse group of fans from around the world who shared interests. This increased her confidence in her writing, and thus reshaped her position within the community to successful author. The second dynamic was the realization that her identity as a speaker of Chinese and her knowledge of Asian languages and cultures were valuable resources for her fanfiction texts. This realization helped her reposition herself as an expert. Thorne and Black conclude that such digital spaces can offer L2 learners a wide range of possibilities “for self-representation and the construction of identities as capable users of multiple social languages” (ibid., p. 276).

Summary

L2 learners inhabit multiple, intersecting social identities, both real and imagined, which are significant to the development of their semiotic repertoires in that they mediate in important ways learners’ access to their opportunities for language learning. Depending on transportable identities such as gender, race, and social class, situated identities such as learners and spouses, and activity-based identities such as gamers and fanfiction writers, L2 learners may find that the opportunities they have access to are abundant and boundless in some cases, and limited or constrained in others. Digital technologies have expanded possibilities for L2 learning by creating new transnational spaces that afford new identity possibilities. In these worlds, L2 learners are able to perform different, activity-based identities through “creative assembly, aligning themselves with different communities and imagining other identities” (Darvin, 2016, p. 536).

Implications for Understanding L2 Teaching

At the meso level of social activity, L2 learning is mediated by learners’ varied social identities. From an understanding of the inextricable links between social identity and the development of learners’ communicative repertoires, we can derive four implications for understanding L2 teaching.

L2 learners typically enter our classrooms with institutionally ascribed learner identities such as “good” or “struggling”, “hardworking” or “apathetic”, as defined by institutional standards. Taking into consideration only these institutional identities renders invisible the fact that students participate in our learning environments from multiple, complex, and sometime conflicting, identity positions. Our teaching practices cannot ignore these identities but, instead, must treat them as primary resources for teaching and learning. In our practices, we must provide learners with a range of diverse opportunities and positions from which to engage in learning the L2. Our teaching practices must not only help learners recognize how their varied identities mediate their learning both in and out of the classroom; they must also provide them with strategies and practices for drawing on and transforming their identities in ways that positively impact their engagement in learning.

2 As important to our learners’ experiences in the classroom are their imagined identities and communities. Together with our learners, we must explore the identities and communities that are both desirable and possible for them. We must be mindful, however, that any unspoken beliefs we may have about learners’ possibilities do not constrain our explorations. In designing our learning environments, we must take students’ imagined identities into consideration to ensure that the learning is meaningful and relevant; we need to design practices that connect learners’ aspirations to particular registers for realizing their imagined identities and facilitate the expansion of their repertoires. While recognizing the positive potential that incorporating learners’ imagined identities can have for L2 learning, we must also be mindful that L2 teachers should not assume

the authority to define and assign possible imagined identities for their language learners, nor should they treat them as tabula rasa with regard to students’ life experience. Teachers should remember the limits of their professional and personal influence on their learners, for educators enter the life of students only at some particular point, but the learning experience also happened before and will continue in the future; the most important thing for [L2] teachers is not to discourage their learners’ desire to acquire some new identities.

(Kharchenko, 2014, p. 36)

We, as teachers, also bring multiple complex identities to our classrooms. How our learners perceive us – our gender, social class, nationality, our roles as academics, spouses, parents etc. – shapes their expectations of us, their interactions with us, and, more generally, their experiences in our classrooms. Teachers who understand their own identities and both the opportunities and constraints they make possible in terms of their relationships with students can use their understandings to develop teaching practices that build relationships with their students, which, in turn, can significantly heighten students’ engagement in their learning contexts.

Digital technologies and social networking sites will continue to expand possibilities for activity-based identity construction and community participation for our L2 learners. We need to reimagine the role that our classrooms can play in linking learners to these virtual worlds and enhancing their ability to be “semiotically agile and adept across communicative modalities” (Thorne, Sauro, & Black, 2015, p. 229). While we do not have to be experts in these technologies and virtual social worlds, we must be cognizant of their affordances and able to design contexts of learning that facilitate our learners’ participation and expansion of their semiotic repertoires.

Pedagogical Activities

This series of pedagogical activities will assist you in relating to and making sense of the concepts that inform our understanding of L2 learning as mediated by learners’ social identities.

Experiencing

A. Social Identities

Create a diagram using, for example, an identity chart or wheel (or other type of diagram) of what you consider to be your most significant transportable, situated, and activity-based identities. Figure 6.1 is an example of an identity chart. For each identity, note a few types of learning experiences that the identity affords and a few types that it constrains. Compare your representations with those of your classmates and consider the following questions:

What are the similarities, what are the differences?

What conclusions can you draw about social identity and your own learning experiences?

B. Language Teacher Identities

Describe yourself in terms of your teacher identities. If you are not yet a teacher, describe your imagined teacher identities. Then, consider the following quote. First, restate it in your own words and then discuss it in terms of your own professional identity development. Relate it to experiences you have had or can imagine having. What implications are there for your future as an L2 teacher?

Figure 6.1 Identity chart.

the negotiation of teachers’ professional identities is… powerfully influenced by contextual factors outside of the teachers themselves and their preservice education…. [T]he identity resources of the teachers may be tested against conditions that challenge and conflict with their backgrounds, skills, social memberships, use of language, beliefs, values, knowledge, attitudes, and so on. Negotiating those challenges forms part of the dynamic of professional identity development.

(Miller, 2009, p. 175)

Conceptualizing

A. Concept Development

Select two of the concepts listed in Box 6.1. Craft a definition of each of the two concepts in your own words. Create one or two concrete examples of the concept that you have either experienced first-hand or can imagine. Pose one or two questions that you still have about the concept and develop a way to gather more information.

Box 6.1 Concepts: L2 learning is mediated by learners’ social identities

activity-based identities

imagined communities

imagined identities

situated identities

social identities

transportable identities

B. Concept Development

Choose one of the concepts you selected from the list on which to gather additional information. Using the internet, search for information on the concept. Create a list of five or so facts about it. These can include names of scholars who study the concept, studies that have been done on the concept along with their findings, visual images depicting the concept, and so on. Create a concept web that visually records the information you gathered from your explorations.

Analyzing

A. Social Identity and L2 Learning

Choose one of the following memoirs, in which the author recounts his/her experiences learning an additional language. After reading the book, write an essay in which you address the following questions.

What events in the author’s life does the memoir focus on?

How does the author position him/herself relative to the language being learned?

What identities seem to play a role in how the author positions him/herself and how the author is positioned by others?

What conclusions can you draw about social identity and L2 learning?

William Alexander (2014). Flirting with French: How a language charmed me, seduced me, and nearly broke my heart.

Deborah Fallows (2011). Dreaming in Chinese: Mandarin lessons in life, love, and language.

Katherine Russell Rich (2009). Dreaming in Hindi: Coming awake in another language.

Ilan Stavans (2002). On borrowed words: A memoir of language.

Dianne Hales (2009). La Bella Lingua: My love affair with Italian, the world’s most enchanting language.

B. Social Identity and L2 Learning

With a partner or group members, conduct a small study on social identity and L2 learning in which you interview a group of adult L2 learners on their experiences learning another language. First, choose a group of learners you are interested in discovering more about and seek their consent to participate. You may also be required to seek approval from your institutional human subject review board. Develop a set of open-ended questions on the topic for the interview. Record each interview (be sure the equipment works well beforehand!) and transcribe the recordings. Content analysis is a useful technique for systematically analyzing such data. Read through the set of interviews first. Next, define your categories, e.g., types of identities, types of L2 learning experiences, and so on. Reread the interviews, and mark keywords and phrases that correspond to the categories. Interpret your findings and report them in a multimodal text to be shared with others. For assistance in conducting a content analysis, conduct a search for materials using an internet browser.

Applying

A. Social Identity

Create a multimodal memoir that recounts how a significant experience or experiences in your trajectory as an additional language learner (re)shaped aspects of your social identities and/or led to the development of new identities. Share with your classmates and/or others by publishing on a shared platform.

B. Digital Communities and Activity-Based Identities

Choose two or three online communities and/or social networking sites in which you regularly participate. Create a multimodal text in which you 1. describe each site and the different types of activity-based identities the site affords you and 2. reflect on the role(s) that your participation in these digital spaces plays in (re)shaping your registers and your identities. Consider two or three ways you can draw on your experiences in your online worlds to apply to the work you do as an L2 teacher.

References

Bauman, R. (2000). Language, identity, performance. Pragmatics, 10(1), 1–5.

Bourdieu, P. (1991). Language and symbolic power. Oxford: Polity.

Bucholtz, M., & Hall, K. (2005). Identity and interaction: A sociocultural linguistic approach. Discourse Studies, 7(4–5), 585–614.

Cekaite, A., & Evaldsson, A.-C. (2008). Staging linguistic identities and negotiating monolingual norms in multiethnic school settings. International Journal of Multilingualism, 5(3), 177–196.

Chen, H. (2013). Identity practices of multilingual writers in social networking spaces. Language Learning & Technology, 17(2), 143–170.

Curtis, A., & M. Romney (2006). Color, race, and English language teaching: Shades of meaning. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Dagenais, D. (2003). Accessing imagined communities through multilingualism and immersion education. Special issue of Language, Identity and Education, 2, 269–283.

Dagenais, D., Toohey, K., & Day, E. (2006). A multilingual child’s literacy practices and contrasting identities in the figured worlds of French immersion classrooms. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 9, 205–218.

Darvin, R. (2016). Language and identity in the digital age. In R. Darvin & S. Preece (Eds.), Routledge handbook of language and identity (pp. 523–540). Oxford: Routledge.

Darvin, R., & Norton, B. (2014). Social class, identity, and migrant students. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 13(2), 111–117.

Douglas Fir Group (2016). A transdisciplinary framework for SLA in a multilingual world. The Modern Language Journal, 100, 19–47.

Duff, P. A. (2015). Transnationalism, multilingualism, and identity. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 35, 57–80.

Gee, J. P. (2017). Identity and diversity in today’s world. Multicultural Education Review, 9(2), 83–92.

Hall, J. K. (2011). Teaching and researching language and culture, 2nd ed. London: Person.

Hruska, B. L. (2004). Constructing gender in an English dominant kindergarten: Implications for second language learners. TESOL Quarterly, 38(3), 459.

Ibrahim, A. E. K. M. (1999). Becoming Black: Rap and hip-hop, race, gender, identity, and the politics of ESL learning. TESOL Quarterly, 33(3), 349–369.

Kanno, Y., & Norton, B. (2003). Imagined communities and educational possibilities. Journal of Language, Identity, and Education. Special issue on. 2(4), 241–249.

Kharchenko, N. (2014). Imagined communities and teaching English as a second language. Journal of Foreign Languages, 2(1), 21–39.

Kubota, R., & Lin, A. (2006). Race and TESOL: Introduction to concepts and theories. TESOL Quarterly, 40(3), 471–493.

Lam, W. S. E. (2004). Second language socialization in a bilingual chatroom. Language Learning & Technology, 8, 44–65.

Lam, W. S. E. (2009). Multiliteracies on instant messaging in negotiating local, translocal, and transnational affiliations: A case of an adolescent immigrant. Reading Research Quarterly, 44(4), 377–397.

Lin, A., R. Grant, R. Kubota, S. Motha, G. Tinker Sachs, & Vandrick, S. (2004). Women faculty of color in TESOL: Theorizing our lived experiences. TESOL Quarterly, 38(3), 487–504.

McKay, S. L., & Wong, S.–L. C. (1996). Multiple discourses, multiple identities: Investment and agency in second-language learning among Chinese adolescent immigrant students. Harvard Educational Review, 66, 577–608.

McKinney, C. (2007). “If I speak English does it make me less black anyway?” “Race” and English in South African desegregated schools. English Academy Review, 24(2), 6–24.

Menard-Warwick, J. (2009). Gendered identities and immigrant language learning. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Miller, E., & Kubota, R. (2013). Second language identity construction. In J. Herschensohn & M. Young-Scholten (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of second language acquisition (pp. 230–250). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Miller, J. (2009). Teacher identity. In A. E. Burns & J. C. Richards (Eds.), The Cambridge guide to second language teacher education (pp. 172–181). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Miller, J. M. (2000). Language use, identity, and social interaction: Migrant students in Australia. Research on language and social interaction, 33(1), 69–100.

Morita, N. (2009). Language, culture, gender, and academic socialization. Language and Education, 23(5), 443–460.

Norton, B. (2000). Identity and language learning. Harlow: Pearson Education

Norton, B. (2001). Non-participation, imagined communities, and the language classroom. In M. Breen (Ed.), Learner contributions to language learning: New directions in research (pp. 159–171). Harlow: Pearson Education.

Norton, B., & McKinney, C. (2011). Identity and second language acquisition. In D. Atkinson (Ed.), Alternative approaches to second language acquisition (pp. 73–94). New York: Routledge.

Norton, B., & Toohey, K. (2011). Identity, language learning, and social change. Language Teaching, 44, 412–446.

Ochs, E. (1993). Constructing social identity. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 26, 287–306.

Pavlenko, A. (2001). Language learning memoirs as a gendered genre. Applied linguistics, 22(2), 213–240.

Pavlenko, A., & Norton, B. (2007). Imagined communities, identity, and English language teaching. In J. Cummins & C. Davison (Eds.), International handbook of English language teaching (pp. 669–680). New York: Springer.

Pierce, B. N. (1995). Social identity, investment and language learning. TESOL Quarterly, 29, 9–31.

Shin, H. (2012). From FOB to cool: Transnational migrant students in Toronto and the styling of global linguistic capital. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 16(2), 184–200.

Shin, H. (2015). Everyday racism in Canadian schools: Ideologies of language and culture among Korean transnational students in Toronto. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 36(1), 67–79.

Skilton-Sylvester, E. (2002). Should I stay or should I go? Investigating Cambodian women’s participation and investment in adult ESL programs. Adult Education Quarterly, 53(1), 9–26.

Song, J. (2010). Language ideology and identity in transnational space: Globalization, migration, and bilingualism among Korean families in the USA. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 13(1), 23–42.

Thorne, S. L., & Black, R. W. (2011). Identity and interaction in internet-mediated contexts. In C. Higgins (Ed.), Identity formation in globalizing contexts (pp. 257–278). De Gruyter.

Thorne, S. L., Sauro, S., & Smith, B. (2015). Technologies, identities, and expressive activity. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 35, 215–233.

Toohey, K. (2000). Learning English at school: Identity, social relations, and classroom practice. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Toohey, K., Day, E., & Manyak, P. (2007). ESL learners in the early school years. In J. Cummins & C. Davison (Eds.), International handbook of English language teaching (pp. 625–638). Boston: Springer.

Tracy, K. & Robles, J. (2013). Everyday talk: Building and reflecting identities, 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press.

Weedon, C. (1997). Feminist practice and poststructuralist theory, 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell.

Wenger, E. (2010). Communities of practice and social learning systems: The career of a concept. In C. Blackmore (Ed.), Social learning systems and communities of practice (pp. 179–198). London: Springer.

Zimmerman, D. H. (1998). Identity, context and interaction. In C. Antaki & S. Widdicombe (Eds.), Identities in talk (pp. 87–106). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.