6

Intercameral

Relations in a

Bicameral Elected and

Sortition Legislature

John Gastil and Erik Olin Wright propose a hybrid bicameralism, with one chamber composed of elected politicians and the other of ordinary citizens chosen by sortition. Though they envision interactions between the two chambers as a “creative tension,” the question of intercameral relations deserves more careful attention. We argue that the chambers would not only have different virtues but also different legitimacies, which might become particularly conflictual if each chamber has the power to veto the proposals of the other, as Gastil and Wright recommend. If the elected chamber proves less popular than the sortition one, the legitimacy of elections might come into question. In turn, elected representatives might try to discredit the sortition representatives as, for example, lacking experience or accountability.

To imagine these intercameral relations, picture a triangular relationship among the two chambers and the public. To understand how those relationships might develop, we wanted to get a preliminary measure of the public support for each mode of selection. In addition, we sought to grasp current political support for sortition among elected officials. We investigated these questions in Belgium, where the idea of sortition has received particular attention in recent years. We conducted a survey among a representative sample of the Belgian population and Belgian members of parliament (MPs) to assess their views of sortition, if it were used for political representation.

As we explain in detail later, the results show that a pure sortition chamber will be difficult to achieve politically, due to limited public support and even lower support among politicians. Our findings also suggest that, once installed, a sortition chamber might continue to face resistance and opposition from the political class. Hence, to test the viability of Gastil and Wright’s sortition chamber proposal, we must imagine intercameral relations and their effects on the perceived legitimacy of the two chambers.1 Beyond our survey findings, we also offer theoretical reflections on the respective legitimacies of elections and sortition—and on their potential antagonisms. This leads us then to consider the effects of different possible distributions of power between the chambers as a crucial determinant of their interactions.

Conflicting legitimacies are not a problem per se. For instance, in existing democratic systems, the relations between legislative, executive, and judiciary powers involve constant tension between their respective rationales. Nonetheless, it cannot be taken for granted that the coexistence of an elected and a sortition chamber would strengthen, rather than weaken, the overall balance of legitimacy in a democratic system. Sortition could challenge the very basis of electoral legitimacy, so intercameral interactions must be considered carefully.

We begin by explaining why Belgium is the right site for investigating these issues; then we present the results of our survey. In the second section, we explore the complementary virtues and competing legitimacies of elections and sortition in theoretical terms. We then draw on our data regarding legitimacy perceptions—and on more general observations about bicameral interactions in contemporary democracies—to consider different potential distributions of power between the two chambers and their potential political consequences. We will review four institutional scenarios: 1) an elected and a sortition chamber having identical powers; 2) the elected one being subordinated; 3) the sortition one being subordinated; and 4) a single mixed chamber, which combines elected and sortition representatives. We weigh the pros and cons of these four options in light of both our data and our theoretical considerations.

Public and Political Perception of Sortition in the Belgian Context

Belgium provided an ideal setting for our surveys because the political debate on sortition in that country has received considerable public attention.2 In addition to proposals made by scholars and activists, several politicians recently advocated the use of random selection to draw citizens into political decision-making. Some have proposed, more specifically, using sortition to select members of the Senate (that is, the Belgian upper house). Hence, debates have addressed the competence and legitimacy of randomly selected representatives, as well as the best institutional design for including lay citizens in the legislative process. Some argue for a parliamentary committee chosen by sortition, others for a mixed Senate combining election and sortition, and others prefer a full sortition Senate.

If the public debate about a sortition chamber is now vivid in Belgium, it does not mean that the proposal has a popular majority. Most Belgian political parties have refused to take an official position on the idea, and current proposals lack serious legislative follow-up. Nonetheless, versions of the idea keep reappearing in media and political debates.3

To get a more precise estimate of political and public support for a sortition chamber, or other variations on that idea, we surveyed members of the regional and national parliaments in Belgium, along with a representative sample of Belgian citizens. For MPs, data was collected via online and paper questionnaires from June to August 2017, with a response rate of 26 percent (N = 124). (Appendix figure 6.A2 shows sample demographics.) The survey company iVox collected a representative online sample of citizens (N = 966).

Our survey examined whether, in light of the contemporary mistrust of the political class, respondents would show more confidence in a sortition chamber than an elected one. We also measured public and political support for the general idea of a sortition chamber, as well as for the idea of a chamber that mixed randomly selected citizens and elected politicians—a method close to the model of the Irish Constitutional Convention.4 Finally, because of our interest in power distribution between chambers, we asked who should make the final decision when the two chambers disagree.

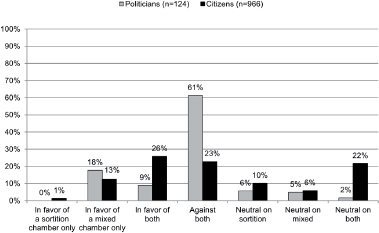

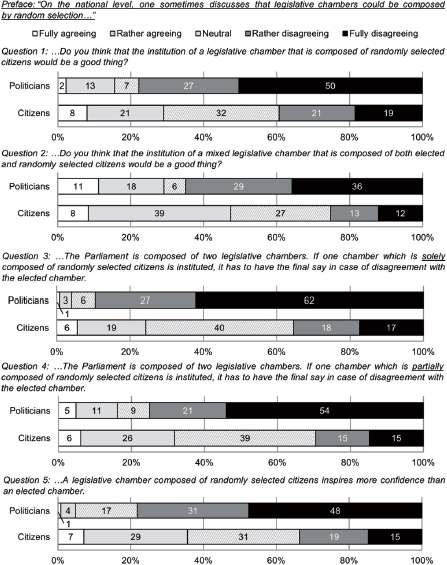

The main results of our survey appear in figure 6.1, which includes the exact question wording for both politicians and citizens. (Appendix figures 6.A1 through 6.A6 display these results in more detail.) As for MPs, the data shows a highly critical posture toward the use of sortition for the appointment to parliament: 77 percent disagree with installing a sortition chamber.5 Nearly two-thirds of politicians (65 percent) also oppose a mixed chamber. When considering the scenario of a disagreement between elected and sortition chambers, 89 percent want the elected chamber to make the final decision, with 75 percent having that view if the second chamber is mixed. Finally, only 5 percent place more confidence in sortition than in an elected chamber, with 17 percent remaining neutral. (That is the highest neutrality score among our five questions.)

Figure 6.1. Distribution of survey responses for politicians (n=24) and citizens (n=966).

For the representative sample of citizens that we surveyed, the picture is quite different, though we do find majority support for neither sortition nor a mixed chamber. Many respondents remained neutral, with a high of 40 percent unsure whether to make elected or sortition members the final authority. This suggests considerable room for movement in public opinion, if the debate on sortition intensifies. When citizens do take a position, we find a much closer split between those who favor or oppose these propositions. More citizens oppose than support the sortition chamber (40 percent versus 29 percent), but a plurality (47 percent) favor a mixed chamber, with only one-quarter of respondents opposing it.

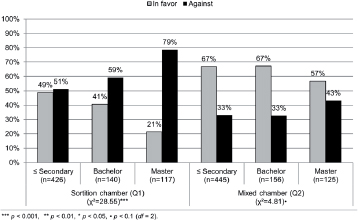

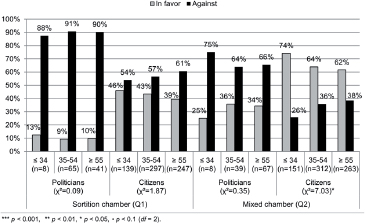

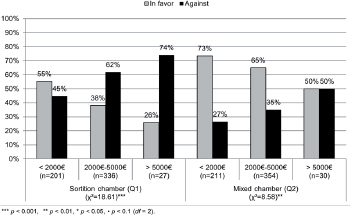

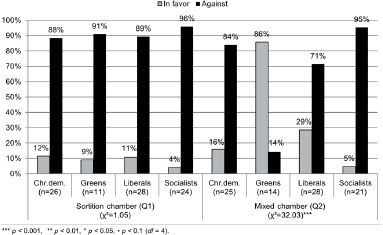

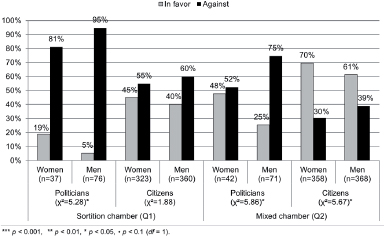

To check whether support for sortition or mixed chambers varied by respondents’ partisan identity or demographic characteristics, we conducted chi-square tests of independence. Table 6.1 shows several statistically significant differences. (More detail appears in appendix figures 6.A2–6.) The most striking result was that of the fourteen Green MPs surveyed, all but two supported establishing a mixed chamber. As for gender, for samples of both politicians and citizens, women were less critical than men toward sortition and more supportive toward a mixed chamber. In the public sample, 74 percent of younger respondents (thirty-four and under) supported a mixed chamber, compared to less than two-thirds (63 percent) of their older counterparts (thirty-five and over). Finally, citizens with the highest levels of formal education and income were least supportive of sortition or a mixed chamber—by margins of 10 to 30 percent—relative to respondents with the lowest income and education levels. (For detailed breakdowns, see appendix figures 6.A5–6.)

Table 6.1: Chi-square coefficients of the support for a sortition (Q1) and mixed (Q2) chamber.

Politicians |

Citizens |

||||

| Tested variable | Sortition chamber |

Mixed chamber |

Sortition chamber |

Mixed chamber |

|

df |

χ2 |

χ2 |

χ2 |

χ2 |

|

Party affiliation |

4 |

1.05 |

32.03 ** |

- |

- |

Gender |

1 |

5.28 ** |

5.86 ** |

1.88 |

5.67 ** |

Age |

2 |

0.09 |

0.35 |

1.87 |

7.03 ** |

Education |

2 |

- |

- |

28.55 ** |

4.81 * |

Income |

2 |

- |

- |

18.61 ** |

8.58 ** |

These results come at a moment in history when neither a sortition nor mixed chamber exists, and there has been no robust debate of such proposals. Nonetheless, the data offer insight into the nearterm prospects of these ideas in the Belgian context—or perhaps in any similar country when these ideas first begin to percolate.

First, MPs strongly oppose the idea of a full sortition chamber, whereas citizens remain ambivalent. By comparison, a mixed chamber appears more achievable. A plurality of citizens favor it, and fewer MPs oppose it. Whether a mixed chamber could serve as a stepping stone toward full sortition is a question our survey cannot address.

Second, politicians’ strong opposition to the introduction of sortition confirms that the proposal is not yet on the legislative agenda—Greens being an interesting exception. We were not surprised that the proposal is resisted by those who have a vested interest in the status quo. In other words, our results can be interpreted as a confirmation that elites see sortition as an existential threat.

Third, there is openness to a sortition body composed of lay citizens. Although there is no clear indication that citizens would be willing to trust a sortition chamber more than an elected one (nor that they trust the latter more), they tend to show more trust in sortition than MPs do. What is more, elections possibly benefit from a psychologically documented status quo bias or path dependency. Whereas sortition, still often perceived as bizarre by people unaware of its historical precedent, could gain popularity if it were to become common practice.

Not only do these results provide some information regarding the achievability of a sortition chamber, but they will also feed into our theoretical analysis of intercameral relations. Before moving to that, we try to shed more light in the following section on the reasons that might explain political resistance to sortition even though it has virtues complementary to elections.

Complementary Virtues and Competing Legitimacies

We agree with Gastil and Wright that sortition and elections have complementary virtues, but our reasoning differs from theirs. By increasing social and cognitive diversity, sortition helps reducing the risks of biased decisions. By freeing representatives from party allegiances and electoral precommitments, it creates conditions for high-quality deliberation. Relative to sortition, however, elections offer a more inclusive space for public participation, leave more room for contestation, include a dimension of choice in the selection of representatives, and provide an (admittedly deficient, yet institutionalized) accountability mechanism.6

There are thus good reasons for trying to combine these respective virtues and for resisting the temptation to abolish the elected chamber as other contributions to this volume suggest.7 Yet nothing guarantees that this combination of elections and sortition will be easy, nor that it will have beneficial effects. The creation of a sortition chamber might further decrease the perceived legitimacy of elected representatives. The unequal public interactions between charismatic elected and unexperienced randomly selected citizens might discredit the latter. Tension between two chambers with veto power might result in political deadlock, to the benefit of those unjustly favored by the status quo. Taken together, these dynamics could undermine public trust in the entire legislative system.

One cannot expect peaceful interaction between the two chambers because elections and sortition embody competing and mutually undermining conceptions of representation. Electoral politics is conceived as a matter of meritocratic competition. A good politician ideally demonstrates political commitment, conviction, persuasive skill, and strategic acumen. The electoral process should bring to power the best representatives, or at least the ones voters want most from the available options. In sortition, everyone is seen as endowed with a capacity for political judgment and able to take active part in collective decision-making.8 Given these conflicting models, tensions arise immediately because sortition challenges the elitist electoral model and the distinctive legitimacy of elected politicians.

The use of sortition also might increase public hostility toward political parties. Modern party politics has many deficiencies, but parties also play positive roles in articulating a multiplicity of societal demands in coherent political programs. Parties organize political majorities and public opposition.9 Yet parties’ legitimacy is closely tied to electoral legitimacy and the conception of representation as competition, which is probably why our survey showed Belgian MPs so strongly opposed to the creation of a sortition chamber.

The important point is that parties and elected representatives will have incentives for trying to delegitimize the sortition chamber.10 If the latter becomes more popular, the incentives could change, as the elected class might become afraid that attacking sortition would undermine its own popularity.11 Yet, in the period of transition toward a widely accepted use of sortition in political representation, it is very important to address this issue of conflicting legitimacies. Failure to do so risks jeopardizing the potential benefits of pairing elections with sortition, and it could delegitimatize completely the very idea of sortition. Thus, we turn to the question of how to reshape existing political institutions such that this conflict becomes an asset, rather than a risk, for democratic legitimacy.

Intercameral Relations

Besides perceived legitimacy, the crucial factor to either increase or decrease the potential intercameral competition will be the distribution of power between the two chambers. Political scientists traditionally draw a distinction between strong and weak bicameralism.12 The main difference between these is not the selection process but the veto power of the second chamber. Either it is an absolute veto (a legislative proposal has to be ratified by both chambers) or a suspensive veto (the second chamber can at most delay the legislative process).13 In the former case, the second chamber performs functions of checks and balances, such as promoting stability, reducing the power of the majority and of the agenda setter, and making corruption more costly. When operating with only a suspensive veto, a body’s function is mostly deliberative, as it works to improve the quality of proposed legislation through amendments or anticipation of the other chamber’s reaction.14

It is an absolute veto power that Gastil and Wright envision for their proposed sortition chamber. Though it is interesting to imagine how the veto power by itself would affect intercameral relations, another part of the picture consists in considering methods for overcoming disagreements between chambers. As we focus on Gastil and Wright’s proposal, we shall limit ourselves in this paper to the examination of the power distribution between the chambers. After having considered the potential effects of an equal distribution of power, we consider the three other alternatives mentioned earlier: a consultative elected chamber, a consultative sortition chamber, and a (single) mixed chamber.

Equal Power: Fight for Public Trust or Mutual Delegitimation?

The main attraction of giving equal power to both chambers comes from the fact that it empowers the sortition body, elevating it to the same standing as its elected counterpart. One might be tempted to see this arrangement as most likely to reap the full benefits of both election and sortition. If both types of representation enjoyed a similar degree of public trust (as in our survey), this might seem like the perfect compromise.

We have our doubts, however. Our main worry relates to a more general criticism of strong bicameralism. If a bill has to pass two chambers to become law, with each having an absolute veto, it becomes more difficult to overcome the status quo, compared to unicameral or weak bicameral systems.15 By itself, this consideration could induce realist utopians to not give veto power to a sortition chamber, or to remove the veto power of the elected one. If capitalism is to be overcome, as Gastil and Wright suggest in their postscript, the status quo does not need unnecessary protections. Equal veto powers for both bodies could also induce constitutional rigidity and thereby create intergenerational injustices.16

Two particular aspects of the dual veto are likely to worsen this status quo bias. First, the preferences of both chambers could diverge significantly. We expect important disagreements between the two chambers because both are likely to become autonomous epistemic communities with their own procedures, functioning, and internal power relationships. What is more, one advantage of representation by lot is supposed to be its capacity to yield a strong deliberative dynamic that is likely to increase the opinion gap with the (less deliberative) elected chamber. Again, the net result is making it harder to overturn the status quo.

Second, the conflictual coexistence of the two chambers would not be mitigated by the presence of political parties in both bodies. When sortition and elected representation coexist, the coagulant function of cross-chamber party platforms is reduced. One cannot expect a sortition chamber to organize itself on partisan affiliations in the same way an elected chamber does. Nor can one expect a sortition chamber to follow the political directions of the government the same way an elected chamber usually does in a parliamentary system. Across the conflicting chambers, legislative votes become more uncertain, the number of negotiating rounds increases, and the entire legislative process slows down further.17 Paradoxically, the increased policy stability (or deadlock) that would result from such a dynamic could lead to even higher social and political conflict.18

Citizens in countries like the US might be so accustomed to political deadlock that such threats do not worry them.19 Nevertheless, the equal power solution presents the greatest risk for the competing legitimacies that we referenced earlier: each chamber might be tempted to contest the very nature and source of legitimacy of the other. For example, the elected chamber could point out the intrinsic incompetence and lack of accountability of the sortition chamber, while the sortition chamber could critique the intrinsic elitism and partisanship of the elected one.

This dynamic could produce widely varying results, some of which could benefit the political system. Conflict between the bodies could spark a more vivid debate between the chambers on policy issues. It could foster a virtuous fight for public trust, if each chamber tries to be the “best” representative of the public. The divergence between the chambers could also result in a larger autonomy of the representative bodies vis-à-vis the executive branch, in a parliamentary system; the sortition chamber would be less subordinated to the government, and the elected chamber could use the negotiations between the chambers as a leverage for acquiring more autonomy.

These optimistic scenarios may come to pass, but equally plausible is a race to the bottom, in which each chamber discredits the other until the public becomes disgusted with both. Structural deadlock could lead an increasing part of the population to think that hybrid bicameralism highlights the complementary vices of sortition and election more than their virtues. This system could lead people to call for a more efficient political body, led by a powerful executive, even if that meant a less democratic government. Given the frequency of irony in political history, such unintended consequences are certainly possible.

A Consultative Role for the Elected Chamber?

If one is worried about the conservative effects of strong bicameralism (or about the risks of de-legitimation of the sortition chamber by the political class), one alternative institutional design subordinates the elected to the sortition chamber. In light of the political resistance to sortition expressed in our survey, this might be the least achievable option, politically. Let us nonetheless consider its theoretical desirability.

If the intended benefits of elections are real, and if the complete replacement of elections would entail a loss for which sortition cannot entirely compensate, this option requires careful design. Sortition must increase the legitimacy of the political system as a whole, not dig the grave of elections.

If the sortition chamber was conceived as (or became) the main chamber, with a mainly consultative role for the elected one, prima facie, this empowers sortition without strong bicameralism’s drawbacks. What is more, a consultative role does not amount to powerlessness: the subordinated chamber (which may keep a constituent role and a power of initiative) usually exercises influence through its suspensive veto power.20 The power to delay decisions gives the subordinate chamber leverage when its counterpart is impatient to pass the legislation, sometimes due to the unreliability of its majority.21

Even so, the social and political status of elections would be affected by setting up a subordinate role. First, if the imbalance of perceived legitimacy between election and sortition increases over time (as people become more acquainted with sortition), the public might encourage the sortition chamber to ignore the elected one. Second, elections provide a moment where political stakes are staged and discussed in the media. Political oppositions and interests are made visible. Representatives are tested and must give account of their actions. Would these functions endure if citizens had the impression that elections matter even less than before? If voter turnout declined, the legitimacy gap between the chambers could grow even wider.

In parliamentary systems, the elected chamber could retain the power to nominate the prime minister. The stakes of legislative elections would thus remain substantial—especially considering the shift of power, in most democracies, from the legislative to the executive branch.22 This would lead to an unprecedented configuration of the relations between the executive and the legislative branch, with one chamber having the power to nominate (and influence) and the other the power to decide. Yet there would also be a high potential for deadlock because governments would have no guarantee of support by the main (sortition) chamber. Under such an arrangement, political parties would face strong incentives to recruit members of the sortition chamber for the government to gain stability and for the opposition to gain strength.

In presidential systems, to the contrary, legislative elections would lose much of their appeal. The political stage would be mainly occupied by two actors—an elected president and the sortition chamber. At first glance, such equilibrium could preserve the main benefits of elections. On closer inspection, however, elections could be reduced to a presidential plebiscitary ritual. In this configuration, there would be a risk of a further shift of power from the legislative branch toward the executive if the former is dominated by the sortition chamber.

A Consultative Role for the Sortition Chamber?

Another institutional alternative gives a consultative role to the sortition chamber. In this scenario, the sortition chamber could enjoy powers of initiative, second reading, and amendment, but the elected chamber would always have the final say. Based on our survey results, this might be the arrangement most acceptable to the political class. If the function of sortition is primarily to empower lay citizens or mitigate an imbalance of power in favor of elites, a subordinate role could appear unsatisfactory. If, however, the sortition chamber is envisioned as a deliberative input in the legislative system, a consultative role might be the best possible fit.

Since power resurfaces whenever the stakes are high,23 a subordinate role might be most suitable for a sortition body, which would then have less risk of corruption by external interests. In the elected chamber, the structures of traditional political parties can provide a firewall between the representatives and external pressures, be they legal (lobbies) or illegal (bribery). Lacking such protection, a fully empowered sortition body would be more susceptible to corrosive external influence.

If we admit that impartiality and deliberative quality are intrinsically or instrumentally valuable, a subordinate sortition chamber might best realize these virtues. By having only a suspensive (and not absolute) veto power, the incentive to produce reasoned recommendations after high-quality deliberations would be increased.24

What is more, a consultative sortition chamber could have substantial influence on the workings of the elected chamber. We have already mentioned how second chambers gain leverage when the elected one fears any further delays. In the particular case of hybrid bicameralism, however, the popularity of the second (sortition) chamber might increase its influence even more. If a sortition chamber were to garner considerable popular support, elected representatives would have a strong incentive to seek its consent—to take into account its suggestions for legislative amendments and to take up its legislative proposals. Knowing that citizens may reward or punish representatives for failing to follow the recommendations of the consultative sortition chamber, the elected majority might be ill advised to neglect its input. Ironically, electoral accountability could thus play in favor of sortition. Yet this will depend on the public identification with the sortition chamber, its media coverage, and the effectiveness of electoral accountability, which is often denounced as poor—not the least by partisans of sortition.

Even if the deliberative effect of a consultative sortition chamber were real, there are risks in this design. The subordinated role might decrease the public’s willingness to serve in the sortition chamber.25 If people fail to see the real power of a consultative chamber, it might create public anger toward an elite that only pretended to give citizens genuine political power. As with the previous arrangements, such drawbacks must be weighed against potential advantages.

What about a Mixed Chamber?

The last institutional option features a chamber composed of both elected and sortition representatives, as was used by the Irish Constitutional Convention. In the Belgian context, several politicians have advocated replacing the current Senate with such a mixed chamber, with the first chamber remaining as it is. This option received the least critical reception by MPs in our survey, and it received the highest public support. A variant of such a scheme would avoid bicameralism’s status quo bias by creating a unicameral—but “bi-representative” —chamber.26

A mixed chamber can mitigate the public battle between professional politicians and lay citizens. If both groups have incentives to work together in subcommittees, they could learn from each other. The public could observe them cooperating closely, exchanging views, and trying to understand each other’s concerns. In light of the contemporary distrust of politics and politicians, this could restore public legitimacy to the legislative process.

Another benefit of a mixed chamber might be that elected politicians who have collaborated with lay citizens would be more willing to defend the recommendations of the mixed chamber in their parties (in government or in the elected chamber if there is one). This, again, would reduce the battle between elected and sortition representatives.

Again, there are risks. Most of all, sortition might lose its intended benefits if mixed with elected representation. Under a unicameral arrangement, this risk would be greatest. The sortition representatives would arrive free from party attachments, but parties would have a strong incentive to form alliances with these unaligned lay representatives. For parties, it could become more appealing to invest time and money in recruiting sortition representatives already chosen than in canvassing the general public to attract more voters. If an additional elected seat requires winning fifty thousand more votes, why not seduce and enroll an independent sortition MP instead? In this scenario, we could imagine a case where a small yet opportunistic party gathers a plurality of (mostly sortition) MPs while earning only a small fraction of the popular vote.

Preventing such political recruitment is hard to imagine, given that parties and sortition MPs would interact on a daily basis and join forces to make majority decisions. Even a rule forbidding political careers after a sortition mandate would not solve the problem entirely. Coalition building is a natural outcome of political battles. If sortition representatives want to weigh on legislative decisions in such a scenario, they will be better off joining existing coalitions—or forming new ones. They might retain more independence than elected representatives, which would attenuate the drawbacks of party discipline, but this outcome would not reap the full fruits of pure sortition.

We believe things might go differently in a bicameral framework scenario, though only where the mixed chamber is subordinate to the elected one. The stakes being lower, party competition might be weaker; hence, the temptation to recruit the sortition MPs into parties might be lower.

Either way, the mixed chamber faces another hazard—the intellectual domination that sortition MPs might suffer when seated among professional politicians. One does not even need to assume hostile intentions on the part of elected representatives. The fact is that there will probably be an asymmetry of experience and self-confidence, which might turn out to be detrimental to sortition representatives. If some participants’ voices are perceived as more legitimate, or more articulate, deliberation could suffer.27 Empirical evidence on this subject is equivocal,28 but to secure high-quality deliberation, such domination must be prevented.

Conclusion

Elections and sortition have complementary virtues that provide promising ground for being combined in a bicameral legislature. At the same time, competing legitimacies need to be considered when thinking about the intercameral distribution of power. Representative surveys of the Belgian population revealed an ambivalent reception of the sortition chamber idea, with many citizens still undecided on the question. Our survey of MPs, however, showed strong resistance to sortition.

Those results go along with our theoretical consideration of sortition and election as having not only different legitimacies, but also competing—and potentially conflicting—ones. The reintroduction of sortition into modern representative systems will be difficult to achieve, but sortition will likely face continued resistance once installed.

For that reason, it is important to try to anticipate the results of potentially conflictual intercameral relations under hybrid bicameralism. A crucial factor affecting intercameral relations will be the distribution of power between the chambers, which Gastil and Wright envision as roughly equal in their proposal. Path dependency can explain their choice for such a strong bicameralism, but it is not enough to justify it. When opening the debate on the introduction of a legislature by lot, one must also open the debate on this distribution of power. We did so by thinking through four scenarios.

First, we considered an equal power solution. Though it appears as the natural combination of the respective virtues of elections and sortition, this institutional design has the effect of protecting the status quo, and it could push the two chambers to mutual delegitimation.

Second, we explored the possibility of subordinating the elected chamber to the sortition one. Such an option appeared more plausible in a presidential system than in a parliamentary one, but either way, it risks political recruitment of sortition representatives, reduced electoral legitimacy, and greater transfer of power from the legislative to the executive branch.

Third, we discussed the scenario of a sortition chamber being subordinated to the elected, while playing a deliberative role. Doing so would probably attenuate, but not annihilate, sortition’s political impact. The ruling majority might be ill advised to neglect the input of the sortition chamber because this would delay its legislative projects and could even jeopardize its future electoral success. Yet a subordinate role for the sortition chamber might also have demotivating effects and engender public frustration.

Finally, we explored the idea of a mixed chamber composed of sortition and elected MPs. The joint work of these two types of representatives could create a positive logic of mutual learning and cooperation. But we also stressed the risks of political recruitment and intellectual domination of the politicians on the lay citizens.

Every one of these power distributions has advantages and drawbacks with important consequences for the political system. If a government decided to undertake such a radical reform, the choice between these different options should be made in consideration of the institutional context and of the societal changes that the reform would seek to achieve.

Five questions, corresponding to those in figure 6.1, were asked with exactly the same wording in our two surveys. Respondents were provided no additional explanations or context for these questions. Table 6.2 shows the response rates for the MP survey, and figure 6.A1 shows the precise choices of politicians and citizens regarding a sortition and a mixed chamber. Figures 6.A2–6 show the detailed response distributions across partisan and sociodemographic dimensions used for the chi-square tests. Support for a proposal was operationalized as the sum of those “fully agreeing” and “rather agreeing,” with the same done for opposition. Respondents with a neutral position were not taken into account for the chi-square tests.

Table 6.2. Response rates for survey among regional and federal members of parliament.

|

Sample |

Population |

Response rate |

Total |

124 |

473 |

26% |

Men |

79 |

283 |

28% |

Women |

45 |

190 |

24% |

Dutch speakers |

56 |

234 |

24% |

French speakers |

56 |

214 |

26% |

German speakers |

12 |

25 |

48% |

Christian Democrats |

29 |

85 |

34% |

Greens |

14 |

40 |

35% |

Liberals |

28 |

106 |

26% |

Socialists |

30 |

115 |

26% |

Nationalists |

13 |

87 |

15% |

Other |

10 |

40 |

25% |

Fig. 6.A2. MPs’ support for a sortition and a mixed chamber by party affiliation.

Fig. 6.A3. Support for a sortition and a mixed chamber by gender.

Fig. 6.A5. Citizens’ support for a sortition and a mixed chamber by education.