Main Points:

Once upon a time, in a faraway land, four blind wise men were asked to describe the true nature of an elephant. Each took a turn touching the beast. One by one, they spoke.

“This animal is long and curved like a spear,” said the first blind man after grabbing a tusk. The next, clutching the giant’s leg, raised his voice. “I disagree! This animal is thick and upright—like a tree.” As they began to argue, the next man touched the ear and compared it to a giant leaf. Finally, the last man, wrapped up in the elephant’s trunk, declared triumphantly that they were all wrong—the animal was like a big, fat snake.

In this story, each man described a part of the elephant. Yet, he was so sure his view was the whole truth, he didn’t consider the possibility that there was another explanation that could account for all the different observations.

Similarly, wise men and women trying to solve the mystery of colic have focused on single bits of truth. Some heard grunting and thought gas was the culprit. Others saw a grimace and thought it was pain. Still others noticed that cuddling helped and assumed the infants were spoiled.

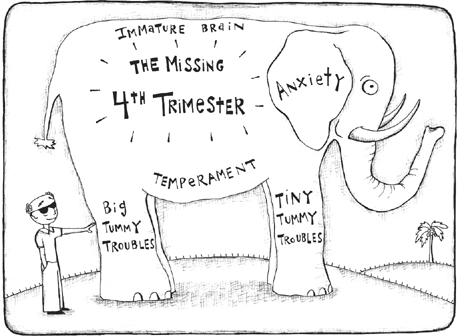

In recent years, colic has been blamed on pain, anxiety, immaturity, and temperament. Yet, while each is a piece of the puzzle, colic can only be understood by viewing all the pieces together. Only then does it become clear that the popular colic theories are linked by one previously overlooked concept: the missing fourth trimester.

Your baby’s nine months—or three trimesters—inside you is a time of unbelievably complex development. Nevertheless, it takes most babies an additional three months to “wake up” and become active partners in the relationship. This time between birth and the end of your baby’s third month is what I call your baby’s fourth trimester.

Now let’s see what a baby’s life is like before they’re born, why they must come into the world before they’re fully mature, and the ways great parents soothe their babies by imitating the womb for the first three months of their baby’s life.

Did you think your baby was ready to be born after your nine months of pregnancy? God knows you were ready! But in many ways, your baby wasn’t. Newborns can’t smile, coo, or even suck their fingers. At birth, they’re really still fetuses and for the next three months they want little more than to be carried, cuddled, and made to feel like they’re still within the womb.

However, in order to mimic the sensations he enjoyed so much in your uterus, you need to know what it was like in there. Let’s backtrack to the time when your fetus was still in the womb and see life through his eyes. Imagine you can look inside your pregnant uterus. What do you see? Just inside the muscular walls, silky membranes waft in a pool of tropical amniotic waters. Over there is your pulsating placenta; like a twenty-four-hour diner, it serves your fetus a constant feast of food and oxygen.

At the center, in the place of honor, is your precious baby. He’s protected from hunger, germs, cold winds, mean animals, and rambunctious siblings by the velvet-soft walls of your womb. He looks part-astronaut—part-merman as he floats weightlessly in the golden fluid. Over these nine months, your fetus develops at lightning speed. His brain adds two hundred fifty thousand nerve cells a minute, and his body grows one billion times in weight and infinitely in complexity.

Let’s zoom in on your baby’s last month of life inside you. It’s getting really tight in there. Like a little yoga expert, your fetus is nestled in, folded and secure. However, contrary to popular myth his cozy room is neither quiet nor still. It’s jiggly (imagine your baby bouncing around when you hustle down the stairs) and loud (the blood whooshes through your arteries, creating a rhythmic din noisier than a vacuum cleaner).

Amazingly, all this commotion doesn’t upset him. Rather, he finds it soothing. That’s why unborn babies stay calm during the day but become restless in the still of the night. It’s an ideal life in there—so why do babies pack up and pop out after just nine months, when they’re still so immature?

Upon thee I was cast out from the womb.

Psalms 22:10

During the past century, archaeologists have pieced together a clearer picture of how humans evolved over the past five million years. They have studied such issues as why we switched from knuckle-walking to running upright and when we began using language and tools. However, what has not been fully appreciated until now is that over millions of years evolutionary changes gradually forced our ancestral mothers to deliver babies who were more and more immature. I believe that eventually, prehistoric human mothers had to evict their newborns three months early because their brains got so big!

In the very distant past, our ancestors likely had tiny-headed babies who didn’t need to be evicted early from the womb. However, a few million years ago, our babies began going down a new branch of the evolutionary tree—the branch of supersmart people with big-brained babies. Pregnant mothers began stuffing new talents into their unborn babies’ brains, filling them up like Christmas stockings. Eventually, their heads must have gotten so large that they began to get stuck during birth.

Perhaps that would have ended the evolution of our big brains, but four adaptations occurred that allowed our babies’ brains to continue growing:

1. Our fetuses began to develop no-frills brains, containing only the most basic reflexes and skills needed to survive after birth (like sucking, pooping, and keeping the heart beating).

2. An ultrasleek head design slowly evolved to keep the big brain from getting wedged in the birth canal. On the outside it had slippery skin, squishable ears, and a tiny chin and nose. On the inside it had a compressible brain and a soft skull that could elongate and form itself into a narrower, easier to deliver cone shape.

3. Their big heads began to rotate as they exited the womb. (You’ve probably noticed it’s easier to get a tight cork out of a bottle if you twist it as you pull it out.)

These three modifications helped tremendously. However, the crowning change that allowed the continued growth of our babies’ brains was the fourth change—“eviction.”

4. I believe that over hundreds of thousands of years, big-brained babies were less likely to get stuck in the birth canal—and more likely to survive—if they were born a little prematurely. In other words, if they were evicted.

Today, mothers give birth to their babies about three months before they’re fully mature in order to guarantee a safe delivery.

However, as any mother can tell you, even with all these adaptations, giving birth is still a very tight squeeze. At eleven and a half centimeters across, our fetuses’ heads have to compress quite a bit to get pushed through a ten centimeter, fully dilated cervix. No wonder midwives call the cervix at delivery the “ring of fire”!

Childbirth has always been a hazardous business occasionally putting both children and mothers in mortal peril. That’s why, through the ages, many societies have honored childbirth as a heroic act. The Aztecs believed women who died giving birth entered the highest level of heaven, alongside courageous warriors who lost their lives in battle.

Imagine giving birth to a baby half the height or weight of an adult. Of course, a three-foot-long, eighty-pound newborn would be ridiculous. Now imagine giving birth to a baby with a head half the size of an adult’s. That sounds even more absurd, but the fact is that such a head would be small for a new baby. At birth, our babies’ noggins are almost two-thirds as big around as an adult head. (Ouch!)

Early eviction lessened that risk and was made possible by the ability of prehistoric parents to protect their immature babies. Thanks to their upright posture and highly developed manual dexterity, early humans could walk while carrying their infants to keep them warm and cuddled. And our ancestors used their hands for more than holding. They created warm clothing and slinglike carriers that mimicked the security of the womb.

The hard work of imitating the uterus was the price our Stone Age relatives accepted in exchange for having safer early deliveries. However, in recent centuries, many parents have tried to wiggle out of this commitment to their babies.

They still wanted their babies to have big smart brains and be born early, but they didn’t want to feed them so frequently or carry them around all day. Some misguided experts even insisted that newborns should be expected to sleep through the night and calm their own crying. Like kangaroos refusing their babies’ entrance to the pouch, parents who subscribed to these theories denied what mothers and fathers for hundreds of thousands of years had promised to give their new infants.

The baby, assailed by eyes, ears, nose, skin, and intestines at once, feels it all as one great blooming, buzzing confusion.

William James, The Principles of Psychology, 1890

When you bring your soft, dimpled newborn home from the hospital, you may think your peaceful nursery is perfectly suited for his cherubic body and temperament, but that’s not how your baby sees it. To him, it’s a disorienting world—part Las Vegas casino, part dark closet!

His senses are bombarded by new experiences. From outside, he’s assaulted by a jumble of lights, colors, and textures. From inside, he’s flooded with waves of powerful new feelings like gas, hunger, and thirst. Yet, at the same time, the stillness of the room envelops him like a closet, devoid of the rhythms that were his constant comfort and companion for the past nine months. Imagine how strange the quiet of a hospital room must be to your baby after the loud, quadraphonic shhhh of the womb. No wonder babies look around as if they’re thinking, This just can’t be real!

Most infants can deal with these changes without a hitch. However, some babies can’t. They need to be held, rocked, and suckled for large chunks of the day. These sensations duplicate the womb and form the basis of every infant-soothing method ever invented. This fourth-trimester experience calms babies not because they’re spoiled and not because it tricks them into thinking they’re back home, but because it triggers a powerful response inside our babies’ brains that turns off their crying—the calming reflex.

The fourth trimester is the birthday present babies really hope their parents will give them.

When the baby comes out, the true umbilical cord is cut forever … yet the baby is still, in that second, a fetus … just a fetus one second older.

Peter Farb, Humankind

What an unforgettable moment the first time you see and touch your new baby. His sweet smell, open gaze, and downy soft skin capture your heart. But newborns can also be intimidating. Their floppy necks, irregular breathing, and tiny tremors make them seem so helpless.

This vulnerability is why I believe that a fourth-trimester period of imitating the womb is exactly what new babies need.

This need was probably obvious to you when your baby’s sobs melted away the moment he was placed on your chest. Your ears and his cry will now become a virtual umbilical cord, an attachment, like an invisible bungee cord that stretches to allow you to walk around the house—until a sharp yelp yanks you back to his side.

“When Stuart came out of me, he didn’t seem ready to be in the world,” said Mary, a mother in my practice. “He required almost constant holding and rocking to keep him content. My husband, Phil, and I joked that he was like a squishy cupcake that needed to go back in the oven for a little more baking.”

In effect, what Mary and Phil realized was that Stuart needed a few more months of “womb service.” But it’s not so easy being a walking uterus! Bewildered new moms often observe that they’re still in their pajamas at five P.M. Within days of delivery, you’ll discover that it takes all day long to accomplish what your uncomplaining uterus did twenty-four hours a day for the past nine months.

From your baby’s point of view, being in your arms for twelve hours a day is a disappointment, if not a rip-off. If he could talk, your infant would probably state with pouty disdain, “Hey, what’s the big deal? You used to hold me twenty-four hours a day and feed me every single second!”

Unfortunately, many parents in our culture have been convinced that it’s wrong to cuddle their babies so much. They have been misled into believing that their main job is to teach and educate their newborn. They treat their young child more like a brain to train than a spirit they are privileged to nurture. Other cultures consider an infant’s needs differently. In Bali, babies are never allowed to sleep alone and they barely leave the arms of an adult for the first hundred and five days! The parents bury the placenta and nourish the burial spot with daily offerings of rice and vegetables. On the hundred and fifth day, a holy ceremony welcomes babies as new members of the human race; up until that point they still belong to the gods. In this ritual, babies receive their first sip of water, and an egg is rubbed on their arms and legs to give them vitality and strength. Only then are their feet finally allowed to touch Mother Earth.

It’s no coincidence that in cultures like Bali, where colic is virtually nonexistent, parents give babies much more of a fourth-trimester experience than we do.

Hide not thine ear to my cry.

Lamentations 3:56

There are at least two things all parents know for sure:

1. There are a lot of spoiled kids out there.

2. You don’t want your child to become one of them.

We all want to raise respectful children, and some experts warn us that being too attentive to our baby’s cries will accidentally teach them to be manipulative. Can promptly answering your newborn’s cries with holding, rocking, and sucking start a bad habit? Can cuddling your baby backfire on you?

Fortunately, the answers to these two questions are … no and no. It’s impossible to spoil your baby during the first four months of life. Remember, he experienced a dramatic drop-off in holding time as soon as he was born. One mother told me, “I imagine new babies feel like someone who enters a detox program and has to go cold turkey from snuggling. No wonder they cry!”

Today’s mothers and fathers aren’t the only ones who have worried about turning their children into whining brats. In the early twentieth century, American parents were told not to mollycoddle their babies for fear of turning them into undisciplined little nuisances. The U.S. Children’s Bureau issued a stern warning to a mother not to carry her infant too much, lest he become “a spoiled, fussy baby, and a household tyrant whose continual demands make a slave of a mother.”

In 1972, however, Sylvia Bell and Mary Ainsworth of Johns Hopkins University shook those old ideas about spoiling to their very foundations. They found that babies whose mothers responded quickly to their cries during the first months of life did not become spoiled. On the contrary, infants whose needs were met rapidly and with tenderness fussed less and were more poised and patient when tested at one year of age! As Ainsworth and Bell proved—and most parents know in their hearts—the more you love and cuddle your little baby, the more confident and resilient he becomes.

Despite this evidence, many new parents still have nagging doubts about whether they’re holding their babies too much. Although our natural parental instinct is to calm our baby as quickly as possible, the repeated warning, “Don’t spoil your baby,” has been drummed into our heads so much it makes us question ourselves.

Now, I admit it’s easy to feel manipulated when your baby wakes up and screams every time you gently lower him into the crib. But letting him cry is no more likely to teach him to be independent than leaving him in a dirty diaper is likely to toughen his skin. (It’s reassuring to know that traditionally many Native American parents held their babies all day and suckled them all night and still those babies grew up to be brave, respectful, and self-sufficient.)

Don’t misunderstand me. I’m not arguing against establishing a flexible feeding/sleeping schedule for your baby. (See the discussion of scheduling in Chapter 15.) Some babies and families find scheduling very helpful. However, trying to mold passionate babies who have irregular sleeping and eating patterns into a fixed schedule usually leads to frustration for everyone.

As the Bible says, “To everything there is a season.” I believe disciplining is a very important parental task—but not with young infants. The beginning of the fourth month is the earliest time concerns about accidentally spoiling your baby become an issue. However, before four months, you have a job that is one hundred times more important than preventing spoiling; your job is nurturing your baby’s confidence in you and the world.

Building our child’s faith is one of parenting’s greatest privileges and responsibilities. I’m convinced that a rapid and sympathetic response to our baby’s cries is the foundation of strong family values, not the undermining of them. When your loving arms cuddle your baby or warm milk satisfies him, you’re telling him, “Don’t worry. I’ll always be there when you need me.” This begins your baby’s trust in you and becomes the bedrock of his faith in those closest to him.

Please treasure these amazing first months with your sweet, kissable baby. There will be plenty of time later on for training and disciplining, but now is the time for cuddling. Enjoy this time because, as any experienced parent will tell you, it will be over faster than you could imagine.

There’s no place like home.

Dorothy, The Wizard of Oz

After centuries of myths and confusion, I am convinced that the true basis of colic is simply that fussy babies need the sensations of the womb to help stay calm.

You might ask, “If all babies get evicted early and need a fourth trimester, why don’t they all get colic?”

The reason is simple: Most babies can handle being born too soon because they have mild temperaments and good self-calming abilities. Thus, despite being exposed to waves of overstimulation and understimulation, they can soothe themselves.

Colicky babies, on the other hand, have big trouble with self-calming. They live through the same experiences as calm babies, but rather than taking them in stride, they overreact dramatically. These infants desperately need the sensations of the womb to help them turn on their calming reflex.

As we’ve discussed, experts have blamed colic on tummy troubles, anxiety, immaturity, and temperament. But, like the blind men and the elephant, these experts perceived only parts of the problem and overlooked the all-important common link—the missing fourth trimester.

The missing fourth trimester makes babies vulnerable to the unstable qualities of their individual natures (brain immaturity and challenging temperament) and to small daily upsets.

This is how I believe all the colic theories relate to one another:

1. Brain Immaturity—This inborn characteristic can greatly increase a baby’s need for a fourth trimester. Fussy infants have such poor state control and self-calming ability that even small amounts of over- or understimulation can set off a chain reaction of escalating flailing and loud cries.

2. Temperament—A baby whose nature is extremely sensitive and/or intense often overreacts to small disturbances and needs a great deal of help turning on the calming reflex.

3. Big Tummy Troubles—Pain from food allergies or acid reflux can occasionally make a baby frantic. But these problems are much more distressing in babies whose self-calming ability is immature or who have challenging temperaments.

4. Tiny Tummy Troubles—Constipation and gas can spark discomfort that provokes crying in babies with brain immaturity and/or a challenging temperament.

5. Maternal Anxiety—Fussy babies sometimes cry more when their anxious mothers handle them too gently or jump chaotically from one ineffective soothing attempt to another.

Putting the Theory of Fourth Trimester to the Test

There’s a reason behind everything in nature.

Aristotle

For a colic theory to be proven correct it must fit all ten colic clues. After long and exhaustive study, I have found the only theory that explains all ten and solves the centuries-old mystery of colic is the concept of the missing fourth trimester:

1. Colicky crying usually starts at two weeks, peaks at six weeks, and ends by three to four months of age.

For the first two weeks of life, newborns have little alert time. This helps keep them from getting over- or understimulated and thus delays the onset of colic.

After two weeks, babies start staying alert for longer periods. Mellow babies can easily handle the stimulation this increased alertness exposes them to. However, babies who are poor self-calmers or who have challenging temperaments may begin to get overwhelmed. Thus the crying starts.

By six weeks, these vulnerable babies are very alert and very overstimulated, yet they still have poor state control. They launch into bouts of screaming that can be soothed only by masterful imitations of the womb.

By three to four months, colic disappears. Now babies are skilled at cooing, laughing, sucking their fingers, and other self-calming tricks. They are mature enough to deal with the world without the constant holding, rocking, and shushing of the fourth trimester. At last, they are ready to be born!

2. Preemies are no more likely to have colic than full-term babies. (And their colic doesn’t start until they are about two weeks past their due date.)

Preemies are good sleepers, even in noisy intensive-care units. Their immature brains have mastered the sleep state, but not the complex state of alertness. This near absence of alert time fools preemies into thinking they’re still in the womb. They don’t notice they’re missing the fourth trimester until they’re past their due date and become more awake and alert.

3. Colicky babies have twisted faces and piercing wails. Often, their cries come in waves (like cramps) and stop abruptly.

Your baby’s colicky cries may sound identical to the wails he makes when he’s in pain. However, many babies overreact to trivial experiences (loud noises, burps, etc.) with pain-like screams. They’re like smoke alarms that go off even though only a little piece of toast burned.

The fact that these shrieks can be quieted by car rides or breast-feeding proves these babies aren’t in agony. What they’re really suffering from is the loss of their fourth trimester.

4. Their screams frequently begin during or just after a feeding.

Babies who cry during or right after meals are usually overreacting to their gastro-colic reflex, the intestinal squeezing that occurs when the stomach fills with food. Most babies have no problem with this reflex, but for colicky babies, at the end of the day (and at the end of their patience), this sensation may be the last straw that launches them into hysterics.

That this distress vanishes after three months (while the gastro-colic reflex is still going strong) further supports the notion that this crampy feeling triggers screaming only in babies who need the calming sensations of the fourth trimester.

5. They often double up, grunt, strain, and seem relieved by passing gas or pooping.

All babies experience intestinal gas; however, this sensation triggers screaming only in infants with sensitive and/or intense temperaments. Even those babies usually stop crying when rescued by the calming rhythms of the womb.

6. Colic is often much worse in the evening (the “witching hour”).

Just as some harried moms crumble at the end of their toddlers’ birthday parties, some young babies unravel after a full day’s roller-coaster ride of activity. Without the fourth trimester to settle them down, these vulnerable infants bubble over each evening like pots of hot pudding.

7. Colic is as likely to occur with a couple’s fifth baby as with their first.

Each new baby represents a reshuffling of their parents’ personal deck of genetic traits. That’s why a couple’s first four babies may be calm and easy to keep happy, while their fifth may inherit traits like sensitivity or poor state control that make him fall apart unless he’s held and rocked all day.

These colicky babies require the sanctuary of the fourth trimester to help them cope until they’re mature enough to soothe themselves.

8. Colicky crying often improves with rocking, holding, shhhhing, and gentle abdominal pressure.

This clue is compelling proof that the true cause of uncontrollable crying in babies is their need for a few more months in the uterus. That’s because each of these calming tricks imitates the womb, and after three months they’re no longer required.

9. Babies are healthy and happy between crying bouts.

If the only reason babies have colic is because they’re born too soon, it’s logical to expect immature infants to be healthy and happy until something pushes them over the edge.

10. In many cultures around the world, babies never get colic.

The babies of the villagers of Bali, the bushmen of Botswana, and the Manali tribesmen of the Himalayan foothills all share one trait: these babies never suffer from persistent crying. When anthropologists study “colic-free” cultures, they find that the mothers in those societies closely follow the fourth-trimester plan. Women hold their infants almost twenty-four hours a day, feed them frequently, and constantly rock and jiggle them. For several months, these moms give their babies an almost constant imitation of the womb.

Only the missing fourth trimester explains all the colic clues. However, if soothing a screaming baby is just a matter of imitating the womb with some wrapping and rocking, why do these approaches so often fail to calm colicky kids? The reason is quite simple: Parents in our culture are rarely taught how to do them correctly.

Thankfully, it’s not too late to learn, and in the next part of this book, I will share with you detailed descriptions of the world’s most effective methods for calming crying babies.