“When people talk, listen completely. Most people never listen.”

—Ernest Hemingway

Main Points:

• The secret to communicating with anybody who’s upset is the Fast-Food Rule (FFR).

• FFR Part 1: Whoever is most upset talks first; the other person listens, repeats back what they’re told, and only then do they take their turn to talk.

• FFR Part 2: What you say to an upset person is not as important as the way you say it (this is what I call finding the “sweet spot”).

• The best parents use the FFR instead of words that hurt, compare, distract, and rush to squelch feelings.

You smile, then your baby smiles, then you smile back. She babbles, you babble, then she gurgles with glee. This little “dance” is your child’s first conversation. The simple back-and-forth of patiently listening … then responding is the basic turn-taking pattern of all human communication.

This little dance is simple and automatic when your toddler is happy. But when he enters meltdown mode it’s easy for you to get sucked in, lose your cool, and start to melt down, too (especially when you are the target of the outburst). This dynamic can lead to an explosive escalation.

But don’t worry! This is exactly when the Fast-Food Rule comes to the rescue.

The What? The Fast-Food Rule!

The What? The Fast-Food Rule!

This silly-sounding rule is the golden rule for communicating with anyone who’s upset. I promise: You’ll be amazed how it works on everyone—from toddlers to teens to temperamental spouses.

In a nutshell, the Fast-Food Rule says: Whenever you talk to someone who’s upset, always repeat his feelings first … before offering your own comments or advice.

Why Is This Called the Fast-Food Rule?

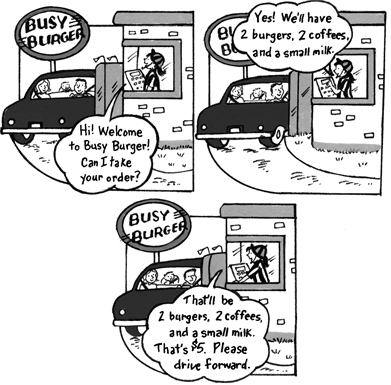

Fast-food joints may have their problems, but they do one thing incredibly well: communicating with customers.

Imagine you’re hungry. You pull up to the restaurant order window and a voice crackles over the speaker, “Can I help you?” You answer, “A burger and fries, please.”

Now … tell me what do you think the order-taker will say back to you?

• “What’s the matter, too lazy to cook tonight?”

• “You should get two burgers, you look hungry.”

• “That’s five dollars, please drive forward.”

The answer is none of the above!

The very first thing she will do is repeat your order to you. She does this because she needs to make sure she understands exactly what you want (“Okay, that’s a burger and fries. Anything to drink?”) before she takes her turn: “That’s five dollars. Please drive up front.”

I mentioned at the start of this chapter that normal conversations have a simple back-and-forth pattern. When we talk, we take turns (“I like chocolate!” “Me too! I love chocolate!”). But this pattern changes dramatically when one person is upset.

The rule for talking to someone who’s upset is: Whoever is most upset talks first (and gets an extralong turn to vent). The other person listens patiently and repeats back his feelings with care and interest (“Wow! What she did really made you angry!”). Only then does the friend get a turn to say what she thinks about the situation.

At fast-food joints, the person who is hungriest gets to speak first. And with parents and children (or in any dialogue between two people), the person who is most upset—the “hungriest for attention”—goes first. This is Part 1 of the Fast-Food Rule.

Is it really so important to take turns like this? Absolutely! Here’s why: Agitated people are terrible listeners. Big emotions (like anger and fear) turn our open minds into closed doors. But once we express our feelings—and they’re acknowledged—our minds swing back open and we can again pay attention to the good suggestions of the people we love.

And There Is One More Critical Point

When you repeat what a person has shared with you about her feelings, what you say (your words) is not as important as the way you say it (your tone of voice, facial expression, and gestures). This is Part 2 of the Fast-Food Rule.

Many Moms and Dads say that the Fast-Food Rule is one of the most important parenting (and life) skills they’ve ever learned. So now let’s see how to use both parts of the FFR (the words you say and the way you say them) in some reallife situations.

FFR Part 1: Restate the Upset Person’s Feelings

Imagine that a woman is frantic because she lost a folder of documents she needs for work. Weeping, she calls her mother: “Mom, I feel so stupid! I left some very important papers on my seat at a restaurant! My boss is going to kill me!”

Immediately the mother interrupts. “It’s okay, sweetheart. I’m sure he’ll understand. Hey, listen to what happened to me yesterday. This will make you laugh….”

In frustration, the woman cries, “You just don’t get it, Mom!”

This mother was in such a rush to soothe her daughter’s pain she instantly tried to distract her and never even acknowledged her upset. That’s like the fast-food order-taker jumping right to “That’s five dollars, drive up front” before repeating your order so that you can confirm it.

Of course, we never want our loved ones to be sad. But failing to acknowledge their feelings only makes them feel unheard, alone, and even more upset!

What if the mother had handled it differently? What if she had first patiently listened to and repeated her daughter’s feelings before she offered a distraction?

“Mom, I feel so stupid! I left some very important letters at a restaurant! My boss is going to kill me!”

“Oh, no!”

“My boss is so rude, I know he’ll scream at me again.”

“No wonder you’re so upset.”

“Yes, I’d been working on that report for two weeks!”

“Nooo! All that effort!”

“Thanks, Mom, for giving me a shoulder to cry on. I’ll get through this somehow.”

“You know I’m always here for you. Hey, listen to what happened yesterday, this will make you laugh….”

When we’re upset the first thing we want from our friends is for them to hear us—lovingly and attentively. Like a waitress repeating our order (“So that’s a burger and fries?”), a friend’s close attention makes us feel understood and respected. Then we are usually much more open to offers of advice, reassurance, or distraction.

Door Openers: A Quick Way to Show You Care

A quick way to show an upset person that you care is by using a door opener.

Door openers are little gestures or comments you make in response to a person telling you his problems. They encourage the person to share his true feelings with you.

Here are a few of the little things you can do and say to encourage your friend to open his heart:

• Raise your eyebrows in surprise.

• Nod your head repeatedly as he talks.

• Say any of the following as you listen:

“Uh-huh.”

“Sure.”

“Wow!”

“I see.”

“Oh, no.”

“You’re kidding!”

“Then what happened?”

“Tell me more….”

The FFR Part 1 … on TV and in Real Life

The next time you’re watching TV, pick out one of the characters and watch her really carefully. Notice the normal turn-taking that goes on in the dialogue. Now notice, when the character gets upset, how the other characters respond to her. Do they: ignore? criticize? distract? immediately reassure? Or do they first respectfully acknowledge her feelings (the FFR)?

Notice, too, that good listeners never ask a person who is crying and obviously upset, “Are you sad?” They just caringly describe what they observe: “I can see how upset you are!”

Okay, now on another day, watch some kids in a park. Notice when they get upset how their parents respond. Do they: ignore? criticize? distract? immediately reassure? Or do they first respectfully acknowledge the feelings (the FFR)?

This exercise will really make you more aware of the power of the right (or wrong) reaction. Pretty soon you will become your friend’s favorite person to talk to!

FFR Part 2: What You Say Is Not as Important as the Way You Say It—Finding the “Sweet Spot”

Most people think that what we say is the key to good communication. Of course, words are very important, but when you’re talking to someone who is upset (mad, sad, scared, etc.), what you say is much less important than the way you say it.

Big emotions trip up our brains! They make our logical left brain (the side that understands words) stumble and stall while allowing our impulsive right brain (the side that focuses on gestures and tone of voice) to hijack the controls.

So when we’re upset, we need someone to respond in a way that will get through to our right brain. That’s why if you pour your heart out to a friend and she just parrots back your words with a blank face and a flat voice, you’ll end up feeling even worse. Even if your listener’s words are totally accurate, if they’re spoken in an emotionless way, you’ll end up feeling like she just doesn’t “get it,” and that will make you feel even worse.

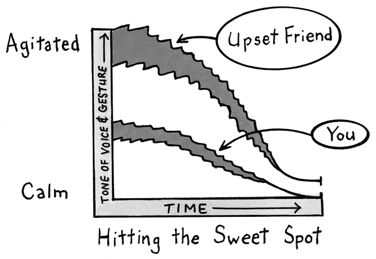

Now that you know how to echo an upset person’s words (FFR Part 1), you’re ready to learn how to put some emotion into your words so your friend feels understood and cared about. Mirroring the right amount of emotion is superimportant. Use too little and your friend will feel you don’t really get it. Use too much and she’ll think you’re being hysterical or making fun of her. I call mirroring just the right amount of emotion “hitting the sweet spot.”

To hit your upset friend’s sweet spot you should try to reflect about one-third of her emotional intensity in your tone of voice, face, and gestures. Then, as she calms, you can gradually return to a more normal way of talking.

Here’s an example to help illustrate the importance of hitting the sweet spot.

Imagine you just got fired and you go to see a friend so that you can pour your heart out. Which of these scenarios would make you feel the most cared about and comforted?

• Your friend, who happens to be a robot, sits perfectly still and mechanically acknowledges your troubles: “Carol … that-is-ter-ri-ble.… You-must-feel-so-sad.”

• Your friend, a drama queen, wildly waves her arms, eyes bugging out in horror, as she blurts, “Oh, no! That’s horrible! You’ll starve!”

Probably neither! The robot’s emotionless delivery feels cold. The hysteric reacts with such a flood of emotion that she may make you feel even more lonely and misunderstood. Most of us prefer our friends to respond with words and gestures somewhere in the middle range of intensity.

• Looking concerned, your friend sighs and says sincerely, “Oh, noooo. Oh, Carol … Oh, noooo.” That may not be terribly eloquent, but it’s deeply comforting because your friend’s tone and expression let you know that she is sympathetic and respectful of your pain. She has connected with your sweet spot.

With a little practice, you’ll find that hitting the sweet spot will become as easy and automatic as returning a smile.

Tips for Finding the Sweet Spot with People of All Ages

In general, a person’s sweet spot is a couple of notches lower than her level of agitation. But it varies from one person to the next. For example:

• Toddlers have really big emotions, so they usually need us to be more demonstrative to reach their sweet spot.

• Shy kids and adult men tend to be less emotionally expressive and may even feel mocked if their feelings are mirrored too closely. They do better when we underplay our response and aim lower to find their sweet spot.

• Teens can be very dramatic, but they don’t like us to be dramatic when we acknowledge their feelings. So “aiming low”—by being caring, but a bit subdued—is usually the best way to hit their sweet spot.

Sylvia told Carla that she could see she was really, really mad, but she did it in a silly, singsong voice that made her three-year-old even madder! When she thought about it, Sylvia realized that by trying to distract Carla and make her laugh at herself for getting so upset, she had prevented Carla from feeling heard and respected. Amazingly, when Sylvia said the same words again, but in a tone that reflected just a bit of her daughter’s upset, Carla quieted in seconds and looked up at her mother with real appreciation.

Practicing the FFR

The easiest way to master this new style of responding is to try it out with a friend who is just a little upset. Narrate your friend’s feelings with a bit of caring emotion on your face and in your voice. Then, as you get more comfortable with the technique, try using it with someone who is very upset.

New habits take time to learn. So don’t worry if you find you keep forgetting to use the FFR at first. Before you know it, you’ll be amazed by how many compliments you get for being a great listener, a great friend, and a great parent.

Common Questions About Using the FFR with Children

Q: Don’t I get to speak first? After all, I am the parent.

A: Of course your child must respect you, and you’ll have many opportunities to teach her that. But when she’s upset, insisting that she wait for you to talk first will make her feel unloved.

We’re forever reminding kids to wait their turn. Well, the best way to teach that is to practice what we preach.

Q: I find the Fast-Food Rule a bit unnatural. Will I ever get used to it?

A: Like any new skill, it takes practice. But most parents find that the FFR becomes almost automatic after just a week or two.

Q: If my child falls and doesn’t cry, do I have to use the FFR?

A: The FFR says to mirror a bit of your child’s response. So if your child doesn’t seem upset about the fall, just casually comment, “Wow! You fell. That was a big boom.”

Q: Should I use the FFR when I think my son’s complaints are unreasonable?

A: Initially, yes. You’ll have an easier time getting him to respect your view if you first let him know that you see his side of things.

Q: Do I ever get to give my message first?

A: Sure. Remember, the FFR says, “Whoever is most upset goes first.” Usually that’s your toddler, but you go first if she’s in danger, being aggressive, or breaking an important family rule (see Chapter 7). After all, in those situations you’re the one who is most upset.

So if your daughter runs into the street when she’s having a tantrum, you go first! Run and grab her and say, “No! No street! Danger! ” Then, once you’re safely back on the sidewalk, you should take a minute to acknowledge her feelings.

After the FFR … It’s Your Turn!

Emotions and learning are like oil and water … they don’t mix! That’s why the moment when your toddler is struggling to escape the car seat is not the best time to give him a lecture about deaths on the highway. Even adults become more unreasonable and illogical when we’re upset. So it should be no surprise that your toddler can’t hear you until the tidal wave of his emotions starts to subside. When your child enters caveman mode, energetically acknowledge his dismay, and then, once he calms a bit, you can try to distract him, reassure him, or solve the problem. Here are some other things you might do and say when it becomes your turn:

• Be physical. Offer a hug, tousle his hair, put a hand on his shoulder, or just sit quietly together.

• Whisper. Whispering is a fun way to change the subject and reconnect.

• Give options. “We can’t have soda, but how about some yummy juice?”

• Explain your point of view … briefly. Save important lessons for a calm time, later on, when he can pay better attention.

• Teach how to express feelings. “Make a face to show me see how sad you are,” or “When I’m mad, I stomp my feet, like this….”

• Talk about how emotions feel, physically. “You were so mad, I bet you felt like your blood was boiling!” or “When I’m scared, my heart goes boom boom like a drum.”

• Grant your child’s wish … in fantasy. (This is one of my favorites.) “I wish I could vroom up all the rain and we could go outside and play right now!”

• Give a “you-I” message. Once the dust settles and it’s your turn to talk, very briefly share your feelings using a “you-I” sentence to help your toddler learn to understand the feelings of others: “When you kick Mommy, I feel mad!” or “When you call me ‘stupid,’ I feel very sad inside.”

The Famous Parental “But”

“I know you want to leave, but …” Parents commonly use the word “but” to mark the end of their upset child’s turn and begin their own. If your tot resists leaving the park, try first repeating her feelings for ten seconds or so: “You say, ‘No leave! No leave!’ You love the park.” Then, as she starts to calm, switch to your turn: “… but, we have to go. Let’s hurry! Then we can play with Daddy at home!”

First you respect your child’s feelings; then you use your enthusiasm to sweep her along to the next activity.

Emotions Are Great: They Make Us Healthy!

Did you know that emotions make us healthy? In fact, the way in which you react to your child’s expression of emotion will contribute greatly to his health—and happiness—for the rest of his life. That’s why the Fast-Food Rule is so important.

However, there’s a huge and important difference between emotions and actions. While many actions are unacceptable, most feelings are legitimate and should be promptly acknowledged (with the FFR).

Of course, you will often have to stop your toddler’s unacceptable actions (fighting, rude words, etc.). But when his strong feelings (anger, fear, frustration, etc.) are ignored or squelched, they don’t just disappear. They continue to simmer under the surface—sometimes for an entire lifetime.

Bottled-up feelings can lead to a profound sense of loneliness (“No one understands”/“No one cares”) or even bursts of hysteria (think drama queen or someone needing anger-management classes). Kids whose words of fear and frustration are repeatedly silenced may grow up emotionally disconnected (like the guy who snarls “I’m NOT angry!”, totally unaware that the veins are popping out of his forehead).

And that’s not all. Unexpressed emotion can also contribute to headaches, colitis, depression … perhaps even arthritis and cancer!

On the other hand, when we “have a good cry” we feel and think better. Venting anger with a good scream or punching a pillow can lower our blood pressure and help us recover, forgive, and move on. Laughter and tears have even been shown to strengthen the immune system and help heal illness.

Children whose feelings are lovingly acknowledged during the toddler years grow up emotionally intact. They know how to ask their friends for help and how to support others in need. They seek out healthy relationships, avoiding bullies and choosing confidantes and life partners who are thoughtful and kind.

Respect: As Important as Love

The magic of the Fast-Food Rule is that it conveys your sincere respect. Respect is not some modern, “airy-fairy,” politically correct concept. It is essential to good relationships. (Of course, love is important too, but disrespect can make even loving relationships crumble.) And to get respect … you must give respect. That is why one of the first things all ambassadors are taught in their training is how to listen and speak with respect.

Respect does not mean letting your toddler run wild. You will often have to enforce your parental authority. But when you are both firm and respectful, you will be modeling to your child exactly the behavior you want to nurture in her.

Don’t worry if it takes you a little time to get the hang of this new way of communicating. Even if you only do the FFR once a day … that’s a great start. And, like riding a bicycle, the more you practice it, the more comfortable you’ll get. I guarantee that soon you’ll feel like you’ve been using the FFR your entire life.

Use the FFR to Replace Some Old Bad Habits

Use the FFR to Replace Some Old Bad Habits

Many of us would never make it as order-takers at Busy Burger. That’s because too often, we cut in line in front of our little child to give our message without first acknowledging his feelings.

Perhaps we feel that our busy schedules—or our wish to make our toddlers feel better fast—justify our pushing their feelings aside and taking a turn first. We don’t mean to be rude. But that’s how it feels to a young child when we skip the FFR.

Throughout time, parents have used all sorts of techniques to stop their kids in the middle of what should be their turn. For example:

| Threatening: | “Stop whining or we’re leaving.” | |

| Questioning: | “What are you afraid of?” | |

| Shame: | “How dare you yell at Grandma!” | |

| Ignoring: | Turning your back and leaving. | |

| Distracting: | “Look at the pretty kitty in the window.” | |

| Reasoning: | “But, honey, there are no more cookies.” |

Did your parents say these things when you were growing up? How did they make you feel?

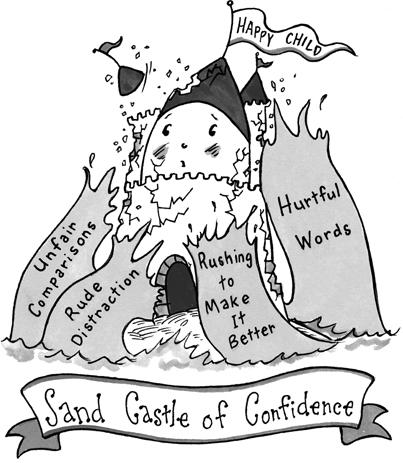

Here are the four most frequent bad habits we fall into when we “elbow” our tot’s feelings aside so we can take the first turn :

• criticizing with hurtful words

• making unfair comparisons

• trying rude distractions

• rushing to “make it all better”

As you develop your skill with the FFR, you’ll drop these like four hot potatoes!

Hurtful Words

“Kimmie, you’re as stubborn as a mule!”

“You’re a scaredy-cat.”

“Why are you so hyper?”

“Don’t be dumb.”

No parent gets up in the morning thinking of ways to crush his child’s confidence with ridicule and sarcasm. That’s why I’m always amazed to see parents assaulting their kids with words like “retard,” “idiot,” and “whiner”—words they’d never allow a stranger to call their child.

Name-calling becomes increasingly hurtful to kids around two years of age because middle toddlers are superfocused on words and they care a lot about what others think.

Often, angry words slip out on a momentary impulse … perhaps echoing mean names thrown at us long ago. (Can you remember being called names when you were growing up? What were they? Does thinking about them still bring up feelings of anger or hurt?)

Verbal attacks can scar like knives. Insults can brutalize a child as much as slapping him. A few cruel remarks can wipe out a hundred hugs and trigger burning resentment or feelings of worthlessness. And what’s even more outrageous is that these names … are always lies! Calling your child a “meathead” is a lie because it focuses on a momentary screwup but ignores the fifteen times he did things well.

Exaggerations Kill (… the Spirit, That Is)

Sweeping statements like “You’re the worst!” “You never help!” or “You always whine!” are exaggerations, and as such, they are usually unfair and always untrue. They make a person feel insulted and demoralized and often lead to resentment and less cooperation!

I recommend you toss the words “always,” “never,” “best,” and “worst” right out of your vocabulary.

So when you’re angry, please skip the yelling and profanity and instead tell your tot how his actions made you feel: “You broke my favorite picture frame, and now Mommy is mad, mad, mad!”

Remember: like an ambassador, you are building a longterm relationship. Can you picture a diplomat telling a king, “You’re so stupid!” or “Shut up!”? Diplomats keep a cool head and a respectful tone even when they’re mad, because they know that today’s enemy is tomorrow’s friend.

Reframe That Name!

Fortunately, compliments and kind remarks also live long in our minds. So replace mean labels that tear your toddler down with descriptions that build him up. It’s one of the best gifts you can give.

| Labels that hurt | Descriptions that help | |

| bossy | a leader | |

| defiant | brave | |

| hyper | energetic, spirited, passionate | |

| nosy | curious | |

| picky eater | discerning, knows exactly what he likes | |

| shy | careful, looks before she leaps | |

| slowpoke | thoughtful, deliberate | |

| stubborn | tenacious | |

| whiny | outspoken |

Unfair Comparisons

How do you feel when someone says, “Everyone else can do it, why can’t you?”

Most of us hate being compared to others, especially when it’s being done as a put-down:

• “Why can’t you act more like your sister?”

• “Stop it! None of the other kids are making such a big fuss.”

Besides being unfair, there are two other big reasons why you should avoid using comparisons to make a point: Before you know it, you’ll be trying to stop your child from imitating some of the bad things that other kids do. And goodness knows you’ll hate it when she starts pointing out how her friend’s parents are nicer than you!

Rude distraction

Distraction works well with babies, so it’s natural to want to use it with toddlers. But be careful. To an upset toddler distraction may feel like a disrespectful interruption or like you’re saying, “Stop feeling your feelings.”

Tara, 14 months old, was thrilled with her new skill—walking. But she was not thrilled to be stuck in my exam room. She headed straight for the exit. “Unghh! Unghh!” she grunted, pushing at the closed door. Then she started slapping it. She wanted out!

Tara’s mom, Simone, briefly acknowledged her tot’s feelings, then moved directly to distraction: “No, sweetheart. I know you want to leave, but we have to stay here just a little longer. Hey, let’s look at this pretty book.” Unfortunately, Simone’s attempt was met with a beet-red face and a shriek that rattled the windows.

Regaining her composure, Simone tried to engage Tara with a cheery verse of “The Itsy-Bitsy Spider.” But again she was met with fiery protests and flailing limbs.

Frustration growing, Simone put her foot down. “Tara! No screaming! Shhhh!” But it was too late. Tara was hysterical. Embarrassed—and annoyed—Simone apologized, tossed her “little volcano” over her shoulder, and, avoiding the stares of the parents in my waiting room, sped out the door.

To understand Tara’s reaction, imagine that you told your best friend about something that upset you, and she responded with a silly change of subject: “Hey, look. New shoes!” I bet pretty soon you’d be looking for a new best friend.

Toddlers also get annoyed when we answer their protests and upsets with distractions. But of course, they don’t have the option of switching parents. So they either accept your distraction, pushing their hurt feelings deep inside, or scream louder, to try to force you to care.

I used to witness this parenting faux pas in my office every day. A toddler cried as I started to examine her ears and her mom instantly started jiggling a doll inches in front of her face, chirping, “Look! Pretty dolly!”

The response? More times than not, the child’s shrieks jumped an octave, as if to say, “Dolly!? Are you kidding? Don’t you see I’m scared?”

Rushing to “Make It All Better”

We often interrupt our child’s complaints with positive comments like “It’s not so bad” or “You’re okay.”

It’s natural to want to comfort your upset child. You just want to “make everything better.” But when your little one is upset, immediately saying “It’s okay!” can actually make things worse. That’s because repeating “It’s okay” over and over again may inadvertently give your child the message that you want her to stuff her feelings deep down inside and act happy even if she isn’t. And that is absolutely not okay.

Monica was preparing a snack for little Suzette—a smiley face made out of grapes, cheese cubes, and crackers.

One day, as a surprise, Monica got even more creative than usual. Instead of whole crackers for the body, she broke them into strips to make arms and legs. But when her 20-month-old saw the broken crackers, she went ballistic.

Monica was so stunned she forgot the FFR and rushed right into trying to make it better, saying, “It’s okay, it’s okay … it’s okay!” But Suzette screamed even louder. With snack time skidding into chaos, Monica found herself repeating, “It’s okay, it’s okay” in an increasingly frustrated and angry voice. In response Suzette just kept shrieking, as if to say, “No, Mom! It’s NOT okay! It’s NOT okay!”

Please, save your reassurance for after you respectfully reflect your child’s feelings (FFR) and she starts calming down. Saying “It’s okay” only makes sense once the child really is starting to feel okay.

Of course, you should immediately help your little one if she’s in pain or terrified. But toddlers are not delicate flowers who need to be protected from all frustration. Challenging situations strengthen a child’s character and resilience. As Wendy Mogel says in her book The Blessing of a Skinned Knee, a child’s struggles have a valuable silver lining—they boost her ability to handle life’s inevitable frustrations.

Don’t misunderstand me: Distraction and reassurance are great—but only when it becomes your turn. Farmers have to plow before they can plant, and parents need to reflect their child’s feelings (and wait for them to start settling) before taking a turn.

Help Your Toddler Express Feelings

Help Your Toddler Express Feelings

Young toddlers (12–24 months): Model for your child how to vent her feelings. For example, when she’s mad stomp your feet, clap your hands, and shake your head vigorously, and teach her to say “No!” (“Evelyn says, ‘No, no, no! Mine, mine! Stop now!’”)

Older toddlers (2–4 years old): When things are calm, have your tot practice different faces: “Show me your happy face … your sad face … your mad face.” Point out pictures in books and say “Look at that sad baby. How do you look when you’re sad?” Cut out magazine pictures of people showing emotions and put them on cardboard cards or in a little “feelings book.” Demonstrate your facial expressions so she can see what you mean: “When I get mad my eyes get small and my mouth gets tight like this [make face].”

Teach your child the words to use when she’s upset. Use pictures in the “feelings book” as a starting point. Ask, “How does that boy feel? Why is that girl sad?” Enrich your child’s vocabulary by using different words. For example, for “mad” you might also use: angry, furious, miffed, boiling, red-hot, etc.

Amazingly, the more you practice these simple steps, the sooner your child will start to gain control of her emotional outbursts.

Now that you are getting the hang of the Fast-Food Rule, you’re ready to learn the second step in becoming the perfect “ambassador”: the perfect way to make the FFR work with any toddler … the language called Toddler-ese.