NAME |

PAGE |

735 |

|

736 |

|

738 |

|

740 |

|

744 |

|

746 |

|

748 |

|

749 |

|

750 |

|

752 |

|

754 |

|

756 |

|

758 |

|

759 |

|

760 |

|

762 |

|

764 |

|

766 |

|

768 |

|

770 |

|

772 |

|

774 |

|

776 |

|

778 |

|

780 |

|

782 |

|

784 |

|

786 |

|

788 |

|

790 |

|

792 |

|

794 |

|

796 |

|

798 |

|

800 |

|

802 |

|

804 |

What makes the World’s Healthiest Foods so full of health-promoting potential is that they are nutrient-rich. What is so essential about these nutrients is that they are needed to sustain our body. An inadequate intake of these nutrients can cause a reduction in our physiological function, leading to poor health since the body doesn’t have what it needs to work properly.

We must therefore rely upon our food to provide us with these important nutrients. The more our foods concentrate these nutrients, the better they are because they can give our body an abundance of what it needs to achieve optimal health. This is why nutrient-rich foods—the World’s Healthiest Foods—form the foundation of our health.

The World’s Healthiest Foods provides an abundance of the wide variety of nutrients you need for optimal function. It is important to remember that these nutrients do not work alone but in concert (synergistically) with other nutrients. Some set the stage for the activity of others or work in unison with them, while some neutralize or balance the effects of others. This is why study after study has shown that diets containing nutrient-rich foods, like the World’s Healthiest Foods, are associated with better health.

The section on Health-Promoting Nutrients will give you detailed information about the function of an array of important nutrients and a list of the World’s Healthiest Foods that provides the best sources of these nutrients. It will provide you with a variety of information on over 30 nutrients and why we need to include foods rich in each nutrient in our “Healthiest Way of Eating.” It features the following information for each nutrient: the richest food sources of the nutrient; the nutrient’s function; the impact that cooking, storage and processing has on it; public health recommendations; how it promotes health; the causes and symptoms of deficiency; and, whether you need to be concerned about consuming too much of it.

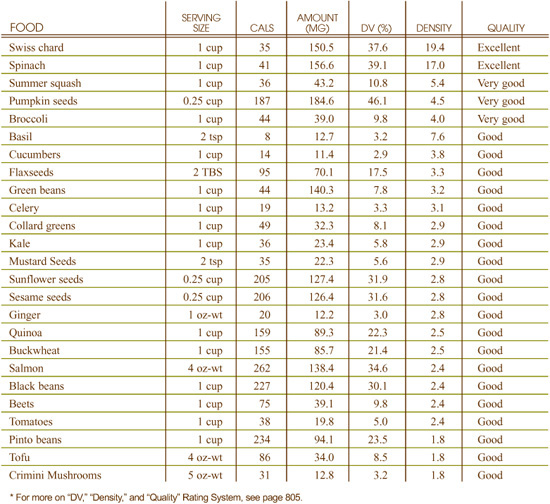

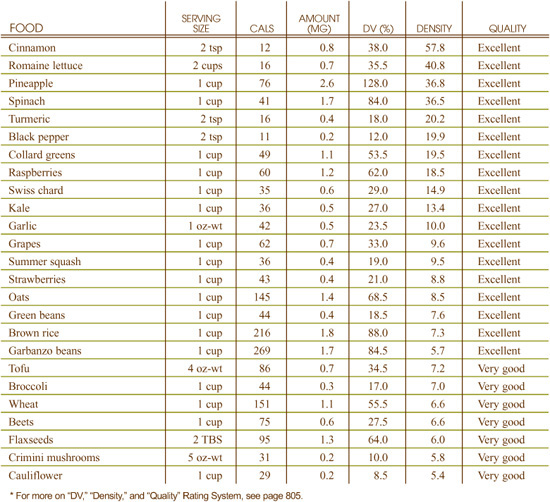

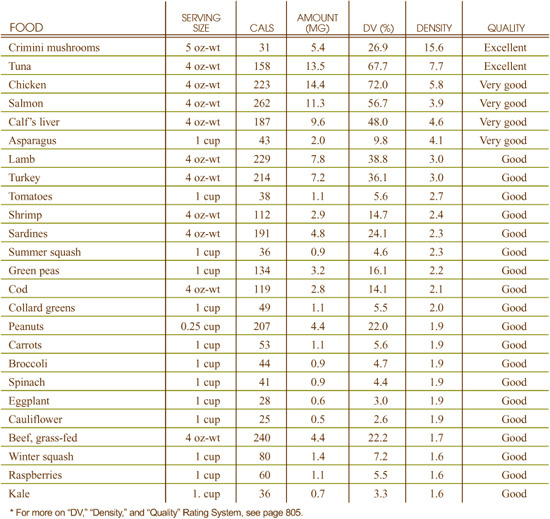

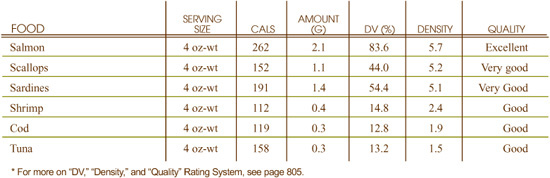

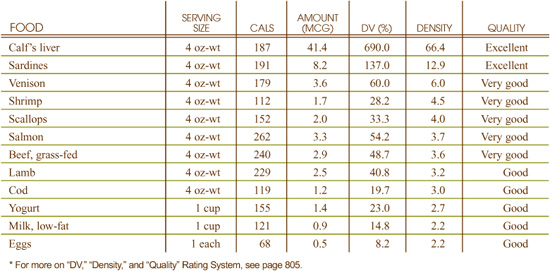

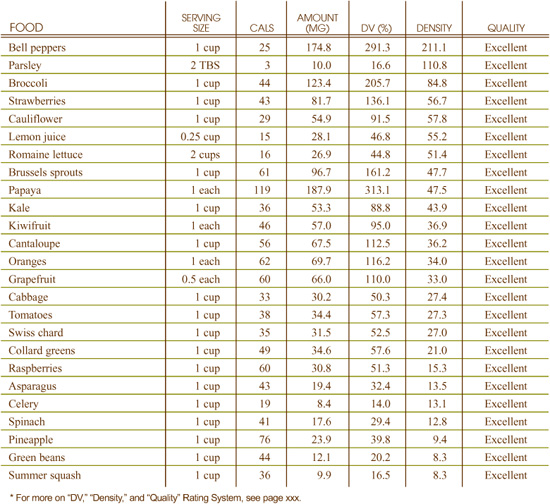

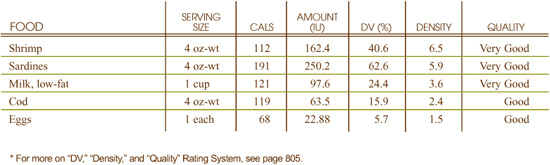

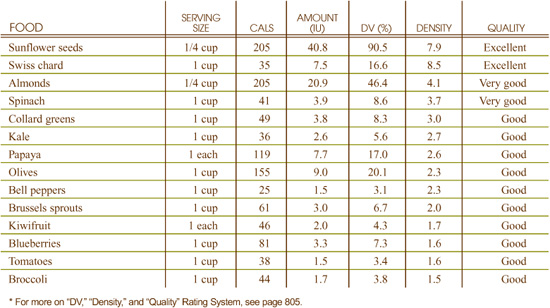

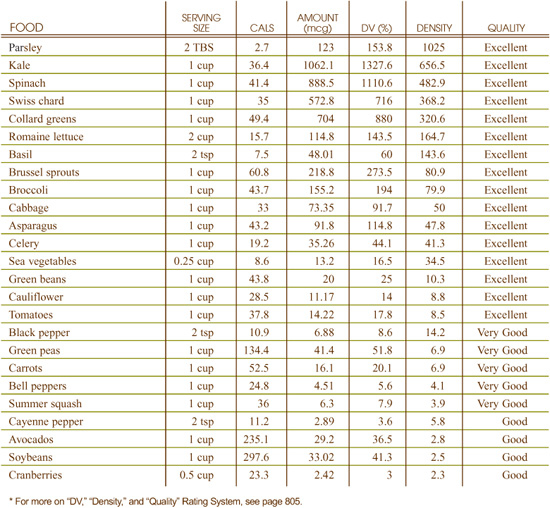

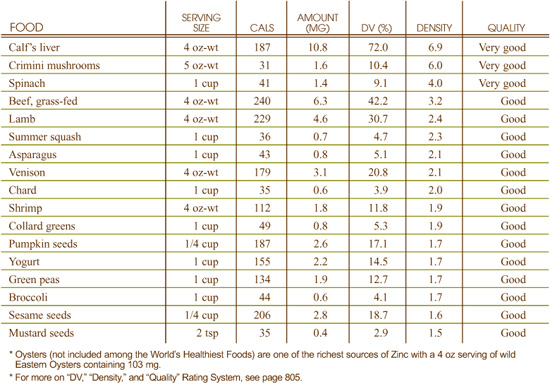

Each chapter includes a Health-Promoting Nutrient chart for that particular nutrient. These charts can serve as valuable tools for helping you to make decisions as to which foods can help you to meet your personal health and nutrition needs. Whether you want to increase your calcium intake to help reduce your risk of osteoporosis or increase your folic acid intake to reduce your risk of cardiovascular disease, these charts will be helpful to you. If you’re looking to jump start your protective defenses during the winter season by consuming more vitamin C-rich foods or find easy ways to increase your content of dietary fiber, you can use the Health-Promoting Nutrient charts to see which foods are excellent, very good and good sources of the nutrient of interest.

Note: If you want help determining your nutritional status and information regarding health-promoting nutrients, which ones may be deficient in your diet, and which foods will help fulfill your nutritional needs, I suggest you go to the home page of the www.whfoods.org website and click on the Food Advisor. The Food Advisor is an interactive program that cannot be replicated in this book. Many thousands of people have been helped by this short, unique questionnaire. It only takes a few minutes to be on your way to vibrant health.

ANTIOXIDANTS ARE DIETARY COMPOUNDS—such as vitamins, minerals, amino acids and phytonutrients—that directly bind to and destroy damaging free radicals. As metabolites of oxidation reactions, free radicals can negatively impact the structure and function of the body in various ways, including: damaging our DNA (see page 75) and causing mutations, which may lead to cancer; oxidizing LDL cholesterol, which is the initiating step in the progression of atherosclerosis; and causing joint damage that can lead to arthritis. As research continues to support the role that free radicals play in the progression of both chronic diseases and other signs of aging, such as the loss of skin elasticity and cognitive function, antioxidants are gaining an ever more important place in health-promoting diets.

Many people are familiar with the vitamins and minerals that are renowned for their antioxidant activity. The ACE vitamins—vitamins A, C and E—as well as the minerals selenium, zinc, copper and manganese are just some of the traditional nutrients that are important when it comes to fighting the damage caused by free radicals. These nutrient antioxidants do not work alone but rather in synergy, each depending upon others to help support its optimal function. Their synergistic relationship is one of the reasons that it is so important to not focus on single nutrient intake, but on intake of an array of nutrients, as offered in the World’s Healthiest Foods.

In the past few years, there have been great contributions made to the arena of antioxidant nutrients, with researchers discovering special compounds in plants—known as phytonutrients—that have potent antioxidant potential. Their discovery of the wide array of phytonutrients, and the fact that so many of them have impressive abilities to prevent oxidative damage, has led researchers to suggest that the presence of these antioxidant phytonutrients may be one of the important reasons why diets rich in vegetables, fruits and other plant-based foods are consistently linked to promoting health and reducing risk of disease.

The wide spectrum of phytonutrients offered by plant-based foods such as fruits, vegetables, whole grains and legumes further supports the fact that these foods can make important contributions to our health. Some researchers estimate up to 40,000 phytonutrients will someday be fully catalogued and understood.

Plants are so rich in antioxidant phytonutrients for a reason: they provide plants with protection from the environmental challenges they face, such as damage from ultraviolet light, toxins, and pollution; when we consume plants rich in phytonutrients, they appear to provide humans with protection as well. Investigating the ways in which phytonutrients provide this protection is one of the most exciting areas in nutrition research today, and recent findings are providing science-based explanations as to how plant foods support our health and wellness.

Some of the major classes of phytonutrients that have antioxidant function include:

• Terpenoids: These include the basic terpenoids like limonene found in citrus foods and menthol, as well as the carotenoids (for more on Carotenoids, see page 740).

• Flavonoids: Flavonoids are the plant pigments that give plants their color. Flavonoids include the anthocyanins in blueberries and quercetin found in onions (for more on Flavonoids, see page 754).

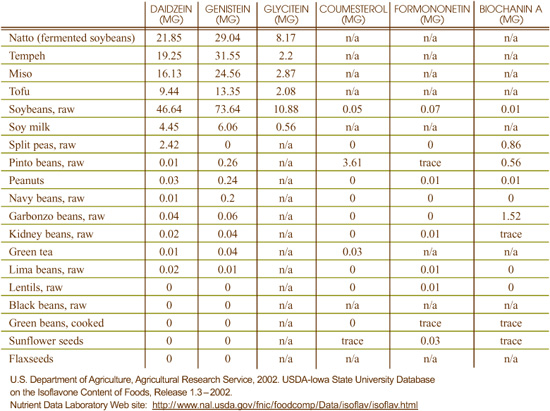

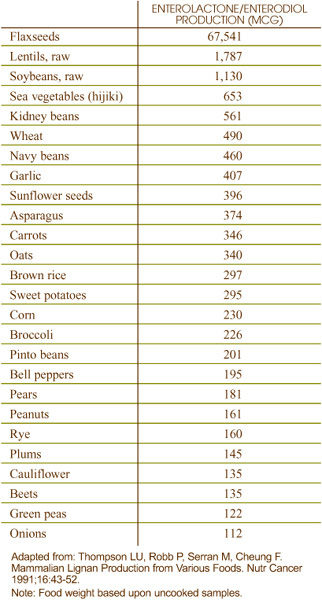

• Isoflavonoids and lignans: Examples include genistein and daidzein found in soy foods, and the lignans in flaxseed and rye.

• Organic acids: Examples include ferulic acid, which is found in whole grains, and the coumarins, which are found in parsley and citrus fruits.

Since many phytonutrients are also responsible for the deep pigments that color our food, one way to look for foods rich in antioxidants is to choose foods that feature a palette of colors. For example, red signals lycopene; yellow/orange, betacarotene and beta-cryptoxanthin; blue/purple, anthocyanins; and green, chlorophyll. Enjoying a spectrum of different colored foods will allow you to enjoy the benefits of a spectrum of antioxidants.

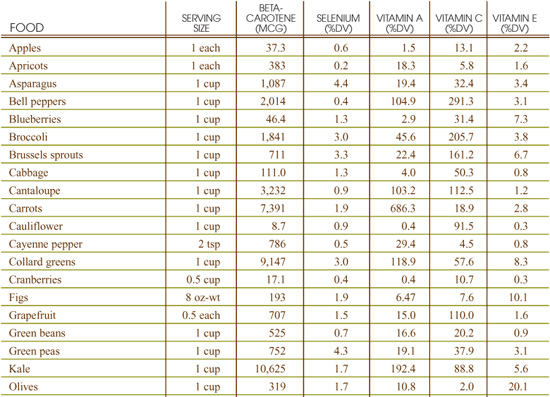

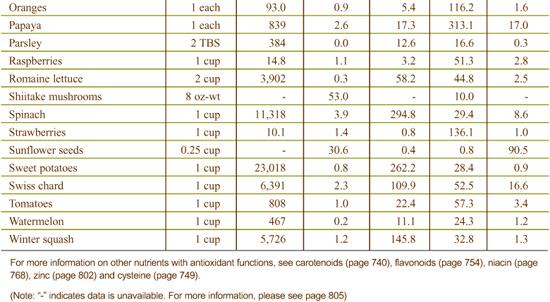

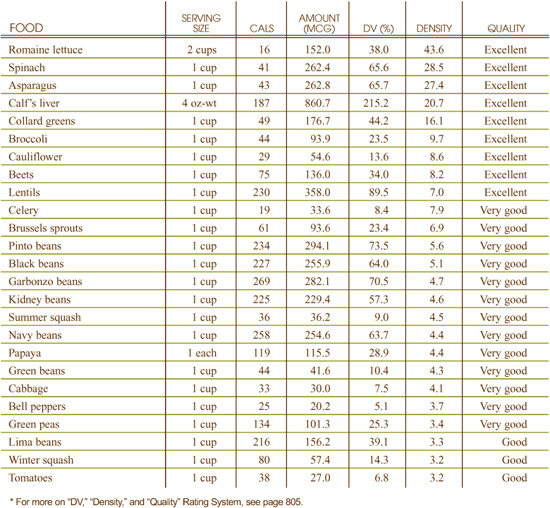

To find foods rich in antioxidants, you can also use the nutrient chapters featured in this section. Look at the chapters for antioxidants such as vitamins A, C, and E, the antioxidant minerals, and carotenoids and flavonoids, and you will find charts that detail the World’s Healthiest Foods that are the richest in those nutrients. In addition, I have also created a chart, located on page 804, which compiles the values of several antioxidant nutrients for some of World’s Healthiest Foods. While this is not an all-inclusive chart, it can give you an idea of the measurement of some antioxidant nutrients in some of your favorite foods.

With the growing interest in antioxidants, researchers are developing ways to measure the overall antioxidant capacity of foods. Instead of measuring specific nutrients, they measure just how powerful different foods (and their compendium of nutrients) are at exerting antioxidant activity. One of the most well known is ORAC, which stands for Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity. While ORAC values have oftentimes been cited as a measurement of a food’s inherent antioxidant potential, there are still very few studies published in Medline that review its use. Since I strongly believe that a food’s antioxidant value is not linked to just one nutrient, but a compendium of its entire matrix, I look forward to more research on ORAC and other measurements of total antioxidant potential of food.

Best World’s Healthiest Food Sources of Antioxidants

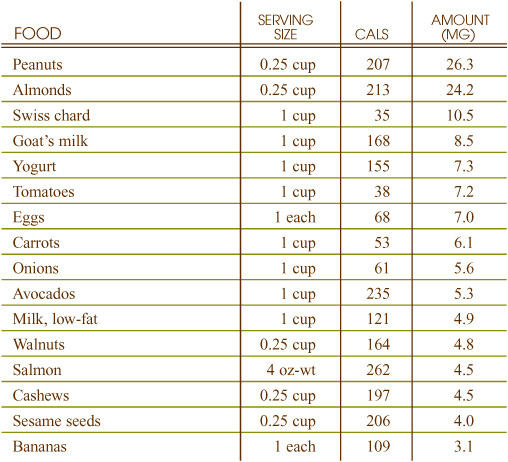

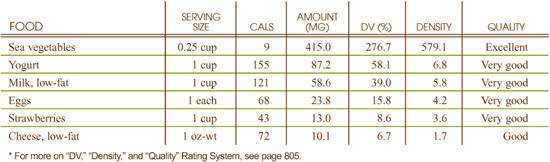

Best Sources of Biotin from the World’s Healthiest Foods

What can biotin-rich foods do for you?

• Support healthy skin through proper fat production

• Help your body make efficient use of sugar

• Maintain an energy supply in your nerve cells

What events can indicate a need for more biotin-rich foods?

• Depression

• Nervousness

• Memory problems

• Red or sore tongue

• Tingling or numbness in feet

• Heart palpitations

Biotin is relatively stable when exposed to heat, light, and oxygen. Strongly acidic conditions, however, can denature this vitamin. In raw eggs, biotin is typically bound to a sugar-protein molecule (the glycoprotein called avidin), and cannot be absorbed into the body unless the egg is cooked, allowing the biotin to separate from the avidin protein.

In 1998, the Institute of Medicine at the National Academy of Sciences issued new Adequate Intake (AI) levels for biotin. The recommendations are as follows:

• 0–6 months: 5 mcg

• 6–12 months: 6 mcg

• 1–3 years: 8 mcg

• 4–8 years: 12 mcg

• 9–13 years: 20 mcg

• 14–18 years: 25 mcg

• 19 years and older: 30 mcg

• Pregnant females of any age: 30 mcg

• Lactating females of any age: 35 mcg

The FDA has set the Reference Value for Nutrition Labeling for biotin at 300 mcg. This is the recommended intake value used by the FDA to calculate the %Daily Value for biotin that may appear on food labels.

The Institute of Medicine did not establish a Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) for biotin.

Biotin plays an integral role in the metabolism of fats, sugars and amino acids. While bacteria in our digestive tract appear capable of making biotin, the extent and dependability of this process is still a matter of debate. For this reason, it’s very important for us to get biotin from our food.

Biotin was discovered in the late 1930s and early 1940s and was originally referred to as “vitamin H.” Egg yolks are one of the richest sources of biotin in the diet, but it is important to not eat whole eggs raw if you want to maximize your biotin consumption. That’s because raw egg whites contain avidin, a sugar and protein-containing molecule that binds together with biotin and prevents its absorption.

Many foods that concentrate biotin also feature vitamin B5 (pantothenic acid), a nutrient that participates in many of the same chemical reactions as biotin.

Biotin is involved in the metabolism of both sugar and fat. In sugar metabolism, biotin helps move sugar from its initial stages of processing to its conversion into usable chemical energy. For this reason, muscle cramps and pains related to physical exertion, which may be the result of the body’s inability to use sugar efficiently as fuel, may signal a biotin deficiency.

Many of the classic biotin deficiency symptoms involve skin-related problems, and the role of biotin in fat synthesis is often cited as a reason for this biotin-skin link. Biotin is required for the function of an enzyme in the body called acetyl Co-A car-boxylase. This enzyme puts together the building blocks for the production of fat in the body. Fat production is critical for all cells in the body since their membranes must contain the correct fat components in order to function properly.

Fat production is especially critical for skin cells since they die and must be replaced very rapidly, and also because they are in contact with the outside environment and must serve as a protective barrier. When cellular fat components cannot be made properly due to biotin deficiency, skin cells are among the first cells to develop problems. In infants, the most common biotin-deficiency symptom is cradle cap—a skin condition in which crusty yellowish/whitish patches appear around the infant’s scalp, head, eyebrows and the skin behind the ears. In adults, the equivalent skin condition is called seborrheic dermatitis, which is not limited to areas around the scalp but can occur in many different locations on the skin.

Because glucose and fat are used for energy within the nervous system, biotin also functions as a supportive vitamin in this area. Numerous nerve-related symptoms have been linked to biotin deficiency. These symptoms include seizures, lack of muscle coordination (ataxia), and lack of good muscle tone (hypotonia).

In addition to lack of biotin-containing foods in the diet, deficient dietary intake of pantothenic acid (vitamin B5) can contribute to a functional biotin deficiency since B5 works together with biotin in many metabolic situations.

Intestinal problems should also be considered as a possible reason for biotin deficiency. Under appropriate circumstances, bacteria in the large intestine can produce biotin, but when intestinal problems create bacterial imbalance, the body is deprived of this alternative source. Consumption of raw egg whites can also contribute to a deficiency since they contain the glycoprotein avidin, which can bind to biotin, preventing its absorption.

Additionally, as many as 50% of pregnant women may be deficient in biotin, a deficiency that may increase the risk of birth defects. Preliminary research has found laboratory evidence of biotin deficiency both in the early (first trimester) and late (third trimester) stages of pregnancy.

Skin-related problems, including cradle cap in infants and seborrheic dermatitis in adults, are the most common biotin deficiency-related symptoms. Hair loss can also be symptomatic of biotin deficiency.

Nervous system-related problems, such as seizures, ataxia, and hypotonia, provide the second most common set of biotin deficiency related symptoms. Additionally, muscle cramps and pains related to physical exertion can be symptomatic of a deficiency, reflecting the body’s inability to use sugar efficiently as a fuel.

Reports of biotin toxicity have not surfaced in the research literature, despite the use of biotin over extended periods of time in dietary supplement doses as high as 60 milligrams (one milligram equals 1,000 micrograms) per day. For this reason, in its 1998 recommendations for intake of B-complex vitamins, the Institute of Medicine chose not to set a Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) for biotin.

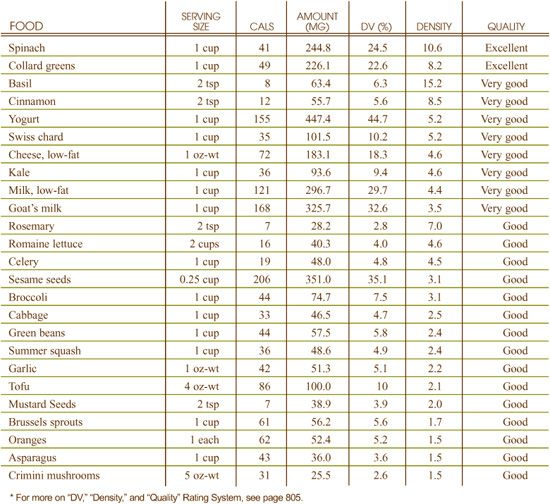

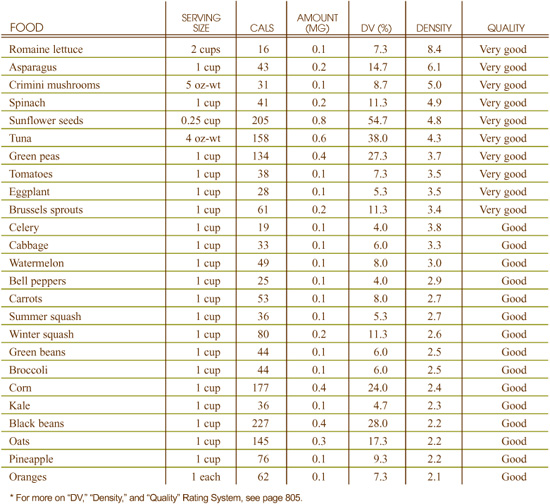

Best Sources of Calcium from the World’s Healthiest Foods

What can calcium-rich foods do for you?

• Maintain healthy, strong bones

• Support proper functioning of nerves and muscles

• Help your blood to clot

What events can indicate a need for more calcium-rich foods?

• Osteopenia (bone-thinning)

• Frequent bone fractures

• Muscle pain or spasms

• Tingling or numbness in your hands or feet

• Bone deformities and growth retardation in children

The amount of calcium in foods is not adversely impacted by cooking or long-term storage.

In 1998, the Institute of Medicine at the National Academy of Sciences issued new Adequate Intake (AI) levels for calcium. The recommendations are as follows:

• 0–6 months: 210 mg

• 6–12 months: 270 mg

• 1–3 years: 500 mg

• 4–8 years: 800 mg

• 9–18 years: 1,300 mg

• 14–18 years: 1,300 mg

• 19–30 years: 1,000 mg

• 31–50 years: 1,000 mg

• 51+ years: 1,200 mg

• Postmenopausal women not taking hormone replacement therapy: 1,500 mg

• Pregnant and lactating women, younger than 18 years: 1,300 mg

• Pregnant and lactating women, older than 19 years: 1,000 mg

The FDA has set the Reference Value for Nutrition Labeling for calcium at 1,000 mg. This is the recommended intake value used by the FDA to calculate the %Daily Value for calcium that may appear on food labels.

The Institute of Medicine established the Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) for calcium at 2,500 mg.

Minerals, like calcium, cannot be made in the body, and therefore must be attained through the foods that we eat. Calcium is one of the most abundant minerals in the human body, accounting for approximately 1.5% of total body weight. While calcium has a lot of important functions, one of its most notable is to promote bone health and prevent osteoporosis. In fact, a calcium-deficient diet is one of the factors that has been linked to the development of osteoporosis.

Other nutrients—such as magnesium, phosphorus, and the trace minerals zinc, copper and boron—also play an important role in enhancing bone density and appear in many calcium-rich foods. Therefore, gaining calcium through your diet will not only provide you with a natural source of this important nutrient, but also of others that act synergistically to promote your health. Although dairy foods have been traditionally promoted as a concentrated source of calcium, many green vegetables provide more calcium per calorie than do milk or milk products.

Getting enough calcium from your diet is specifically important in these modern times when many people’s diets are filled with calcium-depleting factors. For example, sodium, caffeine, the phosphates in carbonated beverages, and excessive consumption of protein can cause an increase in calcium excretion.

Calcium is best known for its role in maintaining the strength and density of bones. In a process known as bone mineralization, calcium and phosphorus join to form calcium phosphate, a major component of the mineral complex hydroxyapatite that gives structure and strength to bones. If dietary calcium intake is too low to maintain normal blood levels to satisfy calcium’s other important functions, the body will draw on calcium stores in the bones to maintain normal blood concentrations, which, after many years, can lead to osteoporosis.

Calcium also plays a role in many other physiological activities including blood clotting, nerve conduction, muscle contraction, regulation of enzyme activity, and cell membrane function.

In addition to insufficient calcium intake, there are other factors that can cause calcium deficiency.

Lack of stomach acid impairs the absorption of calcium and may lead to poor calcium status. Hypochlorhydria, a condition characterized by insufficient secretion of stomach acid, affects many people and is especially common in older individuals.

Adequate intake of vitamin D is necessary for the absorption and utilization of calcium. As a result, vitamin D deficiency, or impaired conversion of the inactive to the active form of vitamin D (which takes place in the liver and kidneys), may also lead to a poor calcium status.

In children, calcium deficiency can cause improper bone mineralization, which leads to rickets, a condition characterized by bone deformities and growth retardation. In adults, calcium deficiency may result in osteomalacia, or “softening of the bone.” Calcium deficiency, along with other contributing factors, can also result in osteoporosis.

Low levels of calcium in the blood (especially one particular form of calcium, called free ionized calcium) may cause a condition called tetany, in which nerve activity becomes excessive. Symptoms of tetany include muscle pain and spasms, as well as tingling and/or numbness in the hands and feet.

Excessive intakes of calcium (more than 3,000 mg per day) may result in elevated blood calcium levels, a condition known as hypercalcemia. If blood levels of phosphorus are low at the same time as calcium levels are high, hypercalcemia can lead to the calcification of soft tissue. This condition involves the unwanted accumulation of calcium in cells other than bone. These negative impacts of excessively high calcium intake prompted the Institute of Medicine to establish a Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) of 2,500 milligrams for intake of calcium through either food and/or dietary supplements.

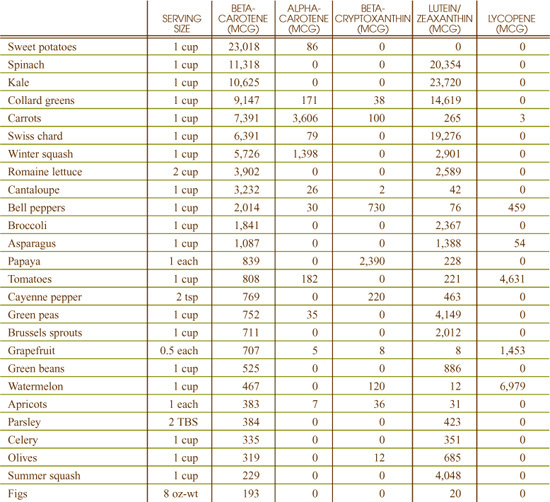

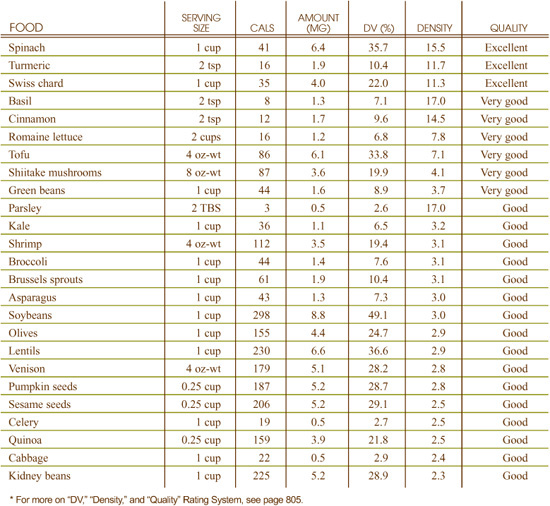

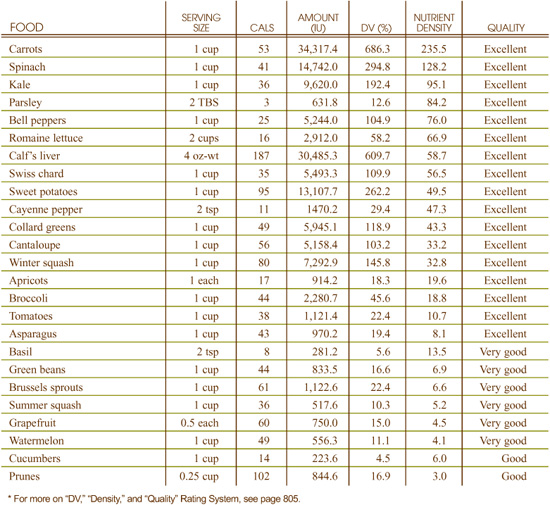

Best Sources of Carotenoids from the World’s Healthiest Foods (betacarotene, alpha-carotene, beta-cryptoxanthin, lutein/zeaxanthin, lycopene)

What can carotenoid-rich foods do for you?

• Protect your cells from the damaging effects of free radicals

• Provide a source of vitamin A

• Enhance the functioning of your immune system

• Promote eye health

• Promote lung health

What events can indicate a need for more carotenoid-rich foods?

• Low intake of fruits and vegetables

• Smoking

• Regular alcohol consumption

In certain cases, cooking can improve the availability of alpha- and betacarotene in foods. Lightly steaming carrots and spinach improves your body’s ability to absorb carotenoids in these foods. It is important to note, however, that in most cases, prolonged cooking of vegetables decreases the availability of these carotenoids by changing the shape of the carotenoid from its natural trans-configuration to a cis-configuration. For example, fresh carrots contain 100% all-trans betacarotene, while canned carrots contain only 73% all-trans betacarotene.

Lutein appears to be sensitive to cooking and storage. Prolonged cooking of green, leafy vegetables is suggested to reduce their lutein content. Additionally, the lutein content of wheat seeds has been found to decline with longer storage times.

Vine-ripened tomatoes have a higher lycopene content than tomatoes ripened off the vine. Although not all scientists agree, it is generally accepted that the availability of lycopene from tomato products is increased when these foods are processed at high temperatures or packaged with oil. If actually true, this means that your body absorbs the lycopene in canned, pasteurized tomato juice and tomato products that contain oil more easily than the lycopene found in a fresh, raw tomato.

While it appears that more research is necessary in this area, a recent study that explored the interrelationship of carotenoid (alpha-carotene, betacarotene and lycopene) absorption with dietary fat consumption seems to be supportive of the oil-carotenoid connection. This study found that the absorption of carotenoids from salad vegetables such as spinach, romaine lettuce, cherry tomatoes, and carrots was much greater with a full-fat dressing than a reduced-fat dressing. This interrelationship makes sense since carotenoids are fat-soluble compounds.

There is minimal research specifically focusing upon the effects of cooking, storage or processing upon beta-cryptox-anthin and zeaxanthin.

In an effort to set public health recommendations, the Institute of Medicine at the National Academy of Sciences reviewed the existing scientific research on carotenoids in 2000. Despite the large body of population-based research that links high consumption of carotenoid-containing foods with a reduced risk of several chronic diseases, the Institute of Medicine concluded that this evidence was not strong enough to support a required carotenoid intake level because it is not yet known if the health benefits associated with carotenoid-containing foods are due to the carotenoids or to some other substance in the food. Therefore, to date, no recommended dietary intake levels have been established for carotenoids.

However, the National Academy of Sciences does support the recommendations of various health agencies, which encourage individuals to consume five or more servings of carotenoid-rich fruits and vegetables every day.

Carotenoids are a phytonutrient family that represents one of the most widespread groups of naturally occurring plant pigments. Alpha-carotene, betacarotene, beta-cryptoxanthin, lutein/zeaxanthin and lycopene are among the most abundant carotenoids in the North American diet.

Alpha-carotene, betacarotene and beta-cryptoxanthin are considered “pro-vitamin A” compounds since they can be converted in the body into retinol, the active form of vitamin A. Among these, betacarotene has the greatest vitamin A activity with the other two having about half that of betacarotene.

Lutein/zeaxanthin and lycopene do share an important characteristic with these “provitamin A” carotenoids—they all have very impressive antioxidant activity. (Although separate molecules, lutein and zeaxanthin are often referred to collectively since they are usually measured together.)

Carotenoids are a great example of why whole foods (rather than dietary supplements) may be the best source of attaining nutrients for most people. While study after study shows carotenoid-rich foods to be of significant importance to preventing chronic disease, the same cannot be said of isolated carotenoid dietary supplements. This fact was brought to public attention when studies suggested that betacarotene supplements were associated with greater risk of developing lung cancer in smokers. While it may be argued that the culprit was that the synthetic carotenoids were in a form not readily acceptable to the body, what cannot be argued is that populations who eat carotenoid-rich foods seem to enjoy better health.

Eating foods rich in carotenoids enhances your body’s usage of these important nutrients since these foods naturally contain other nutrients that act in synergy with carotenoids, supporting their physiological function in your body and therefore contributing to your optimal health. Also, there are probably many other health-promoting carotenoids and phytonutrients contained in whole foods, which science has not yet identified.

Carotenoids are powerful antioxidants, protecting the cells of the body from damage caused by free radicals. While they work in concert, different carotenoids have been found to have unique features. For example, lutein/zeaxanthin are especially active in the eye, protecting the retina and lens from oxidative damage, and therefore protecting against the development of cataracts and age-related macular degeneration. Lycopene is especially effective at quenching a free radical called singlet oxygen and is known for being especially effective at protecting membrane lipids from oxidation, which may be the reason that lycopene intake has been linked with reducing the risk of such health conditions as cardiovascular disease and prostate cancer.

Alpha-carotene, betacarotene and beta-cryptoxanthin are three of the most commonly consumed “provitamin A” carotenoids in the North American diet. Since the body can convert them into retinol, an active form of vitamin A, they can help prevent deficiency of this important nutrient. Among its other functions, vitamin A is important to maintaining a healthy immune system.

Lycopene is also believed to play a role in the prevention of heart disease by inhibiting free radical damage to LDL cholesterol. Before cholesterol can be deposited in the plaques that harden and narrow arteries, it must be oxidized by free radicals. With its powerful antioxidant activity, lycopene can prevent LDL cholesterol from being oxidized. Numerous research studies have also found that diets rich in carotenoid-containing foods are associated with a reduced risk of heart disease.

Carotenoids are found throughout the eyes, with lutein and zeaxanthin being concentrated in the retina and lens. Observational studies have noted that higher dietary intake of lutein and zeaxanthin is related to reduced risk of cataracts and age-related macular degeneration, two eye conditions for which there are minimal options when it comes to effective prevention. Researchers speculate that these carotenoids may promote eye health through their ability to protect the eyes from light-induced oxidative damage and aging through both their antioxidant actions as well as their ability to filter out UV light.

Research suggests that beta-cryptoxanthin may promote the health of the respiratory tract. Serum concentrations of this carotenoid have been found to be associated with improved lung function; individuals who smoke as well as those who inhale second hand smoke have been found to have lower levels of this carotenoid. In addition, the other provitamin A carotenoids—alpha-carotene and betacarotene—may also play a role in promoting lung health since vitamin A itself is known to be necessary for proper growth and development of lung tissue.

Consumption of lycopene-rich foods is associated with a reduced risk of prostate cancer. Recent research has also suggested that lycopene can boost sperm concentrations in infertile men. In one study, a lycopene-supplemented diet resulted in a statistically significant improvement in sperm concentration and motility amongst the 30 infertile men being studied with six pregnancies following as a result of the trial.

Increased intake of beta-cryptoxanthin has been found to be associated with reduced risk of esophageal and lung cancer while intake of lycopene is associated with reduced risk of prostate cancer. One reason that carotenoids may support optimal health is because they have the ability to stimulate cell-to-cell communication, which, if not functioning properly, may contribute to the overgrowth of cells, a condition that eventually leads to cancer.

Carotenoids are fat-soluble substances, and as such require the presence of dietary fat for proper absorption through the digestive tract. Consequently, your carotenoid status may be impaired by a diet that is extremely low in fat or if you have a medical condition that causes a reduction in the ability to absorb dietary fat; these conditions include pancreatic enzyme deficiency, Crohn’s disease, celiac sprue, cystic fibrosis, surgical removal of part or all of the stomach, gall bladder disease, and liver disease.

Due to low consumption of fruits and vegetables, many adolescents and young adults do not take in enough carotenoids. Smokers and drinkers have been found to eat fewer foods that contain carotenoids, while researchers also suspect that cigarette smoke destroys carotenoids.

A low dietary intake of carotenoids is not known to directly cause any diseases or health conditions, at least in the short term. However, if your intake of vitamin A is also low, a dietary deficiency of alpha-carotene, betacarotene, beta-cryptoxan-thin and/or other “provitamin A” carotenoids can cause the symptoms associated with vitamin A deficiency.

Yet, long-term inadequate intake of carotenoids is associated with chronic diseases, including heart disease and various cancers. One important mechanism for this carotenoid-disease relationship appears to be free radicals. Research indicates that diets low in carotenoids can increase the body’s susceptibility to damage from free radicals. As a result, over the long term, carotenoid deficient diets may increase tissue damage from free radical activity, and increase risk of chronic diseases like heart disease and cancers.

High intake of carotenoid-containing foods is not associated with any toxic side effects. As a result, the Institute of Medicine at the National Academy of Sciences did not establish a Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) for carotenoids when it reviewed these nutrients in 2000.

Excessive consumption of betacarotene can lead to a yellowish discoloration of the skin called carotenodermia, while excessive lycopene can lead to a deep orange discoloration called lycopenodermia. Both are harmless and reversible.

While there hasn’t been concern about the safety of carotenoids in foods, there has been some concern raised over the safety of carotenoid dietary supplements as reflected in studies that have shown increased risk of lung cancer in smokers taking betacarotene supplements.

Researchers traditionally have attributed the health-promoting effects of plant foods to their comprehensive array of vitamins, minerals and fiber. More recently, however, research studies are uncovering a new story. Plant foods contain thousands of other compounds in addition to macronutrients (carbohydrates, proteins, fats and fiber) and micronutrients (vitamins and minerals). These other compounds are collectively known as phytonutrients (phyto=plant). Simply put, phytonutrients are active compounds in plants that have been shown to provide benefit to humans when consumed.

Like us, plants are exposed to damaging radiation, toxins and pollution, and this toxic exposure results in the generation of free radicals within their cells. Free radicals are reactive molecules that can bind and damage proteins, cell membranes and DNA. Since plants can’t move away from these insults, nature has provided them with a means of protection: they can make a variety of types of protective compounds—the phytonutrients. When we consume plants rich in phytonutrients, they appear to provide humans with protection as well. Investigating the ways in which phytonutrients provide this protection is one of the most exciting areas in nutrition research today, and recent findings are providing science-based explanations as to how plant foods support our health and wellness.

Most plants use sunlight as an energy source. Although to the eye sunlight appears as a single, clear, bright force, it is actually made up of many different wavelengths, some of which plants capture for the generation of energy. Others, however, are wavelengths from which plants need protection. Each plant contains literally thousands of different phytonutrients that can act as antioxidants, providing protection from potentially damaging free radicals. Many of these compounds also provide the plants with color, with their different colors each reflecting a different variety of protection they provide.

If a plant were only one color, with no shades or variations in that color, it would only be able to receive and protect against one specific wavelength of light. A plant with several different colors is like a television set with an antenna, and a plant with many different colors is like a television with a satellite dish. Most plants have a satellite dish’s worth of colors—even ones that look very green to us when we eat them. Like the primer used beneath a coat of paint, these other colors are simply overshadowed by the primary color that we see.

Some researchers estimate up to 40,000 phytonutrients will someday be fully catalogued and understood. In just the last 30 years, many hundreds of these compounds have been identified and are currently being investigated for their health-promoting qualities. At research organizations like the National Institute of Cancer, and at many universities around the world, different individual phytonutrients are being studied to identify their specific health benefits.

While phytonutrients are classified by their chemical structure, because there are so many compounds, phytonutrients are also lumped together in families depending on the similarities in their structures. Names such as terpenes are used to decribe carotenoids, some of which are precursors to vitamin A and which provide the orange, red and pink colors in foods such as carrots, tomatoes and pink shellfish; limonoids, which are found in citrus fruits and provide them with their distinctive smell; and coumarins, natural blood thinners found in parsley, licorice and citrus fruits.

The phenols, or polyphenols (poly=many), is another family of phytonutrients that has received much research attention and discussion in the scientific literature. In fact, some of the most talked about phytonutrients are in this family. They include the anthocyanidins, which give blueberries and grapes their dark blue and purple color, and the catechins, found in tea and wine, which provide the bitter taste as well as the tawny coloring in these foods. Anthocyanidins have been found to provide unique antioxidant protection from free radical damage in both water-soluble and fat-soluble environments. And, their free radical scavenging capabilities are thought to be more potent than many of the currently well-known vitamin antioxidants; anthocyanidins are estimated to have fifty times the antioxidant activity of both vitamin C and vitamin E. Flavonoids are also commonly considered phenols, although the term “flavonoids” can refer to many phytonutrients.

Lastly, the isoflavones are usually categorized as members of this phenol family. Isoflavones, which are found in soy, kudzu, red clover and rye, have been researched extensively for their ability to protect against hormone-dependent cancers, such as breast cancer.

Other phytonutrients include the organosulfur compounds, such as the glucosinolates and indoles from Brassica vegetables like broccoli, and the allylic sulfides from garlic and onions, all of which have been found to support our ability to detoxify noxious foreign compounds like pesticides and other environmental toxins. Organic acids are another common family of phytonutrients and include some powerful antioxidants, like ferulic acid, which are found in whole grains.

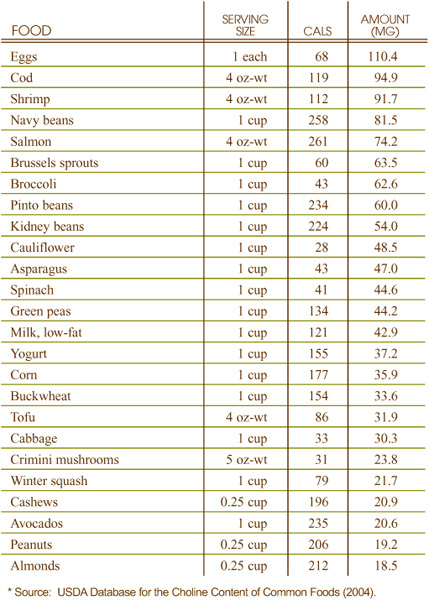

Best Sources of Choline from the World’s Healthiest Foods

What can choline-rich foods do for you?

• Promote proper cell membrane function

• Assist nerve-muscle communication

• Prevent the build-up of homocysteine

What events can indicate a need for more choline-rich foods?

• Fatigue

• Insomnia

• Accumulation of fats in the blood

• Nerve-muscle problems

• Poor ability of the kidneys to concentrate urine

Consistent information is not available on the effects of cooking, storage, and processing on the choline content of food. Like other B complex vitamins, choline can be damaged by overexposure to heat and oxygen, and for this reason overcooking of foods high in choline is not recommended.

In 1998, the Institute of Medicine at the National Academy of Sciences issued new Adequate Intake (AI) levels for choline. The recommendations are as follows:

• 0–6 months: 125 mg

• 6–12 months: 150 mg

• 1–3 years: 200 mg

• 4–8 years: 250 mg

• 9–13 years: 375 mg

• Males 14 years and older: 550 mg

• Females 9–13 years: 375 mg

• Females 14–18 years: 400 mg

• Females 19 years and older: 425 mg

• Pregnant females: 450 mg

• Lactating females: 550 mg

The FDA has not set a Reference Value for Nutrition Labeling for choline.

Details on choline’s Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) are provided under heading “Can You Consume Too Much Choline?”

Even though choline has only recently been officially adopted into the B family of vitamins, it has been the subject of nutritional investigations for almost 150 years. Key research discoveries about choline came in the late 1930s, when scientists discovered that tissue from the pancreas contained a substance that could help prevent fatty build-up in the liver. This substance was named choline after the Greek word chole, which means bile. Since the 1930s, research has shown that choline is found not only in the pancreas and liver, but is also a component of every human cell. In addition to its uniqueness as a fat-modifying substance, choline is chemically unique since it is a trimethylated molecule (a compound that has three methyl groups).

Eating foods rich in choline enhances your body’s usage of this important nutrient since these foods naturally contain other nutrients that act in synergy with choline, supporting its physiological function in your body and therefore best contributing to your optimal health.

Choline is a key component of many fat-containing structures in cell membranes. Since cell membranes are almost entirely composed of fats, the membranes’ flexibility and integrity, key elements of cellular health, depend on adequate supplies of choline. Membrane structures that require choline include phosphatidylcholine and sphingomyelin, which are highly represented in the brain; choline, therefore, is particularly important for brain health.

Choline’s chemical uniqueness as a trimethylated molecule makes it highly important in methyl group metabolism. Many important chemical events in the body are made possible by the transfer of methyl groups from one place to another. For example, genes in the body can be switched on or turned off in this way, and cells can use methylation to send messages back and forth. Choline is also important in the metabolic cycle that keeps levels of homocysteine balanced.

Choline is a key component of acetylcholine, a messenger molecule found in the nervous system that sends messages between nerves and muscles. The neurotransmitter acetylcholine is the body’s primary chemical means of sending messages between nerves and muscles.

In addition to poor dietary intake of choline itself, poor intake of other nutrients can result in choline deficiency. These include vitamin B3 (niacin), folic acid, and the amino acid methionine; all three nutrients are needed in order for choline to obtain the three methyl groups that compose its chemical structure. Additionally, problems including liver cirrhosis are common contributing factors to choline deficiency.

Of special importance in the relationship between choline and health is the impact of choline deficiency on the risk of coronary heart disease and other cardiovascular problems since choline deficiency can lead to homocysteine build-up. Mild choline deficiency has also been linked to fatigue, insomnia, poor ability of the kidneys to concentrate urine, problems with memory, and nerve-muscle imbalances. Choline deficiency can also cause deficiency of folic acid, another B vitamin critically important for health.

The consequences of choline deficiency are particularly visible in the liver since a lack of choline changes the way in which the liver packages and transports fat. The primary symptom of this change in fat packaging is a decrease in the blood level of VLDL (very low-density lipoprotein, a complex fat-containing molecule that the liver uses to transport fat). As part of this same unnatural pattern, levels of blood triglycerides can also become greatly increased as a result of choline deficiency.

Doses of choline in the 5–10 gram/day range have been associated with reductions in blood pressure and in some subjects, feelings of faintness or dizziness. These amounts are typically much higher than the choline content of the foods in the average diet.

In 1998, the Institute of Medicine set the following Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) for choline: for those 1–8 years it is 1 gram; 9–13 years old, 2 grams; 14–18 years old, 3 grams; and, 19 years and older, 3.5 grams.

Best Sources of Chromium from the World’s Healthiest Foods

What can chromium-rich foods do for you?

• Help maintain normal blood sugar and insulin levels

• Support normal cholesterol levels

What events can indicate a need for more chromium-rich foods?

• Hyperinsulinemia; insulin resistance

• High blood sugar levels

• Type 2 diabetes

• High blood pressure

• High triglyceride and total cholesterol levels

• Low HDL cholesterol

Under most circumstances, food processing methods decrease the chromium content of foods. For example, when whole grains are milled to make flour, the chromium-containing germ and bran are removed, and consequently, most of the chromium is lost. On the other hand, acidic foods cooked in stainless steel cookware can accumulate small amounts of chromium by leaching the mineral from the cookware.

In 2001, the Institute of Medicine at the National Academy of Sciences issued new Adequate Intake (AI) levels for chromium. The recommendations are as follows:

• 0–6 months: 0.2 mcg

• 7–12 months: 5.5 mcg

• 1–3 years: 11 mcg

• 4–8 years: 15 mcg

• Males 9–13 years: 25 mcg

• Males 14–50 years: 35 mcg

• Males 51+ years: 30 mcg

• Females 9–13 years: 21 mcg

• Females 14–18 years: 24 mcg

• Females 19–50 years: 25 mcg

• Females 51+ years: 20 mcg

• Pregnant females 14–18 years: 29 mcg

• Pregnant females 19–50 years: 30 mcg

• Lactating females 14–18 years: 44 mcg

• Lactating females 19–50 years: 45 mcg

The FDA has set the Reference Value for Nutrition Labeling for chromium at 120 mcg. This is the recommended intake value used by the FDA to calculate the %Daily Value for chromium that may appear on food labels.

Details on Chromium’s Tolerable Upper Intake Levels (UL) are provided under the heading “Can You Consume Too Much Chromium?”

This essential mineral, required by the body in trace amounts, was first discovered in 1797 by a chemist in France named Louis-Nicolas Vaquelin. Many years later, a physician and research scientist in the U.S. named Walter Mertz discovered that chromium played a key role in carbohydrate metabolism, possibly by participating in formation of a special compound which he named “glucose tolerance factor,” or GTF. Researchers are still not clear whether GTF is an actual chemical compound or not. But they are clear that the nutrients related to GTF—even though they may not be assembled into a single chemical structure—play an important role in blood sugar balance.

Eating foods rich in chromium enhances your body’s usage of this important mineral since these foods naturally contain other nutrients that act in synergy with chromium, supporting its physiological function in your body and therefore contributing to your optimal health.

It is important to eat natural, whole foods since the refinement process strips away naturally occurring chromium. People who consume diets high in simple sugars should be especially careful about consuming enough chromium-rich foods since refined sugars rob the body of chromium by increasing its excretion. Vitamin C increases the absorption of chromium, and many chromium-rich foods come naturally packaged with this important mineral.

As the active component of GTF, chromium plays a fundamental role in controlling blood sugar levels. The primary function of GTF is to increase the cells’ ability to regulate insulin, the hormone responsible for carrying sugar (glucose) into the cells where it can be used for energy.

After a meal, blood glucose levels begin to rise, and, in response, the pancreas secretes insulin, which lowers blood glucose levels by increasing the rate at which glucose enters the cells. To accomplish this, insulin must be able to attach to receptors on the surface of cells. GTF initiates the attachment of insulin to the insulin receptors.

Chromium may also participate in cholesterol metabolism, suggesting a role for this mineral in maintaining normal blood cholesterol levels. In addition, chromium is involved in the metabolism of nucleic acids, which are the building blocks of DNA, the genetic material found in every cell.

If you have diabetes or heart disease, the amount of chromium your body needs may be increased. You may also need extra chromium if you experience physical injury, trauma or mental stress. All of these conditions increase the excretion of chromium. In addition, in the case of stress, the need for increased chromium may be also related directly to blood sugar imbalance. Under severe stress, the body increases its output of certain hormones. These hormonal changes alter blood sugarbalance, and this altered blood sugar balance can create a need for more chromium.

Dietary deficiency of chromium is believed to be widespread in the United States since food processing methods remove most of the naturally occurring chromium from commonly consumed foods. Chromium deficiency leads to insulin resistance, a condition in which the cells of the body do not respond to the presence of insulin. Insulin resistance can lead to elevated blood levels of insulin (hyperinsulinemia) and elevated blood levels of glucose, which can ultimately cause heart disease and/or diabetes. In fact, even mild dietary deficiency of chromium is associated with Syndrome X. This medical condition features a constellation of symptoms, including hyperinsulinemia, high blood pressure, high triglyc-eride levels, high blood sugar levels, and low HDL cholesterol levels, all of which increase one’s risk for heart disease.

Due to the limited nature of existing research studies, the Institute of Medicine at the National Academy of Sciences did not establish set a Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) for chromium. However, in 2001, this organization did make a recommendation that individuals with pre-existing liver or kidney disease be particularly careful to limit their chromium intake.

According to the Encyclopedia of Natural Medicine (Pizzorno and Murray, 1998), more than half of the carbohydrates consumed by people in the United States are added to foods as sweetening agents. Simply put, most of the carbohydrates we eat in this country are in the form of highly processed sugars. The typical American diet consists largely of processed foods that are loaded with refined sweeteners, with names like sucrose (table sugar), maltodextrin, fructose, lactose, and high fructose corn syrup. These sweeteners have the same amount of calories per gram as other, more healthful sources of carbohydrates such as whole grains. But, unlike whole grains, refined sweeteners are called “empty calories” because they do not contain any of the essential nutrients, such as fiber, vitamins, and minerals. Eating too much refined sugar is associated with a variety of health conditions including diabetes, hypoglycemia, obesity, poor immune function, mood fluctuations, dental caries, and premenstrual syndrome.

So, take a step towards better health and try these suggestions for eliminating refined sugar from your diet.

• Eat more fruit: Fruit is rich in naturally occurring sugar that can satisfy your craving for sweets. More importantly, most fruits contain fiber and several vitamins and minerals.

• Cut out the soda: If you are a soda drinker, you are getting too much sugar in your diet, plus a lot of other things that aren’t good for you! Also, don’t think you are doing yourself a favor by drinking fruit beverages. The number one ingredient in many of the fruit drinks sold in supermarkets is high fructose corn syrup. If you want to enjoy a fruit juice, choose a product that contains 100% fruit juice.

• Leave out the spoonful of sugar: Many of us add table sugar to hot and cold beverages. To break this habit, start by cutting the amount of sugar you add to your beverages in half, then slowly eliminate the sugar completely.

• Bake and cook with alternatives: If you like to make cookies and other baked goods, you probably use a lot of white and brown sugar. Try substituting a more natural sugar, such as dried organic cane juice, honey or molasses in your favorite cookie and dessert recipes. In addition, puréed fruits (such as dates, bananas and apples) or 100% fruit juice concentrate can be used in place of white and brown sugar in many recipes.

• Use the World’s Healthiest Foods as the foundation of your diet: The foods featured in this book are whole, unprocessed, and nutrient-rich foods. By incorporating more of these foods into your diet, you will automatically reduce your consumption of refined sweeteners.

What can coenzyme Q-rich foods do for you?

• Help prevent cardiovascular disease

• Improve energy levels

• Stabilize blood sugar

• Restore the power of vitamin E

What events can indicate a need for more coenzyme Q-rich foods?

• Heart problems like angina, arrhythmia, or high blood pressure

• Problems with the gums

• Stomach ulcers

• High blood sugar

• Muscle weakness and fatigue

No research is currently available about the impact of cooking, storage or processing on this nutrient.

The Institute of Medicine at the National Academy of Sciences has not established a Dietary Reference Intake (DRI) nor Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) for coenzyme Q.

Coenzyme Q is extremely important to our health, especially the health of our heart and blood vessels. Its chemical structure was discovered in 1957, and since that time, nearly 5,000 research studies on coenzyme Q have been published.

In many living creatures, the same chemical pathways that make vitamin E, vitamin K, and folic acid also make coenzyme Q. While the human body cannot make these other vitamins, it appears that it can make coenzyme Q.

Coenzyme Q, also called ubiquinone since it is ubiquitiously present in all our cells, is often designated as coenzyme Q10. The number “10” following its name refers to a specific part of its chemical structure.

Coenzyme Q lies at the heart of our cells’ energy producing process. Special organelles (tiny organs) inside our cells, called mitochondria, take fat, carbohydrate and protein, and convert them into usable energy. This process always requires coenzyme Q. In some cells, like heart cells, this energy conversion process can be the difference between life and death, one of the reasons why coenzyme Q is so vital to health.

Coenzyme Q is a well-established antioxidant used by the body to protect cells from oxygen damage. The exact mechanism for this protective effect is not clear. However, in at least one study, up to 95% less damage to cell membranes has been demonstrated following supplementation with coenzyme Q.

Deficiency symptoms for coenzyme Q are not well-studied. However, deficiency of this nutrient has been clearly associated with a variety of heart problems including arrhythmia, angina, heart attack, mitral valve prolapse, high blood pressure, coronary artery disease, atherosclerosis, and congestive heart failure. Problems in regulating blood sugar have also been linked to coenzyme Q deficiency, as have problems with the gums and stomach ulcers.

Certain medications, such as statin drugs or beta blockers, can induce a deficiency of coenzyme Q.

From food sources alone, it would be impossible to obtain the hundred milligram level doses that are thought to be the starting point for toxicity. The Institute of Medicine has not established a Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) for coenzyme Q.

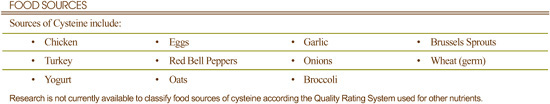

What can cysteine-rich foods do for you?

• Protect cells from free radical damage

• Help your body detoxify chemicals and heavy metals

• Help break down extra mucous in your lungs

What events can indicate a need for more cysteine-rich foods?

• Frequent colds

• COPD (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease)

No research is currently available about the impact of cooking, storage or processing on cysteine.

In 2002, the Institute of Medicine at the National Academy of Sciences set recommended protein digestibility amino acid standards for 9 amino acids or amino acid combinations. A standard of 25 milligrams per kilogram (one kilogram equals approximately 2.2 pounds) of body weight was set for intake of cysteine-plus-methionine combined. This standard applies to all individuals 1 year of age and older. For example, an individual weighing 70 pounds (31.75 kilograms) would require about 800 milligrams of cysteine-plus-methionine, whereas someone weighing 160 pounds (72.5 kilograms) would need about 1,800 milligrams.

Cysteine is an amino acid that occurs naturally in foods and which, with the help of other nutrient cofactors, can also be manufactured in the body from the amino acid methionine. Cysteine has unique functions since it is only one of two amino acids (the other is methionione) that contains sulfur. Cysteine is an important component of the antioxidant glutathione and can also be converted into the amino acid taurine.

Eating foods rich in cysteine enhances your body’s usage of this important nutrient since these foods naturally contain other nutrients that act in synergy with cysteine, supporting its physiological function in your body and therefore contributing to your optimal health.

As a key constituent of glutathione, cysteine has many important physiological functions. Glutathione, formed from cysteine, glutamic acid, and glycine, is found in all human tissues, with the highest concentrations found in the liver and eyes. Glutathione is a potent antioxidant, protecting fatty tissues from the damaging effects of free radicals. The antioxidant activity of glutathione is attributed specifically to the cysteine that it contains.

As mentioned above, cysteine is a key constituent of glutathione, a compound that also plays a vital role in the detoxification of harmful substances by the liver, which can also chelate (attach to and remove from the body) heavy metals such as lead, mercury, and cadmium. It is also believed that glutathione carries nutrients to lymphocytes and phagocytes, important immune system cells. Cysteine also has the ability to break down proteins found in mucous that settles in the lungs.

The production of cysteine in the body involves several nutrients. As a result, dietary deficiency of methionine, vitamin B-6, vitamin B12, s-adenosyl methionine or folic acid may decrease the production of cysteine.

Cysteine deficiency is relatively uncommon but may be seen in vegetarians with low intake of the plant foods containing methionine and cysteine. There is no known medical condition directly caused by cysteine deficiency, but low cysteine levels may reduce one’s ability to prevent free radical damage and may result in impaired function of the immune system.

The Institute of Medicine at the National Academy of Sciences did not establish a Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) for cysteine or other amino acids.

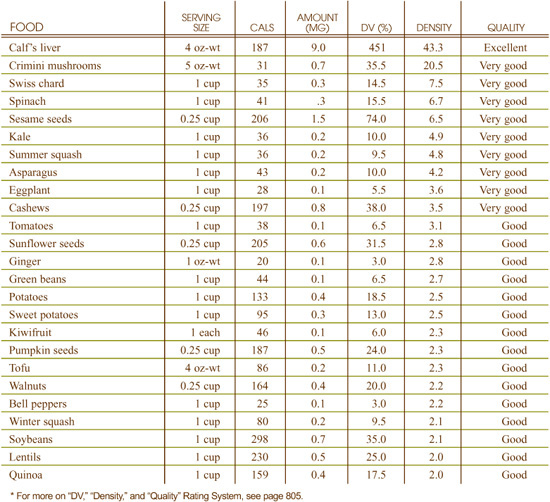

Best Sources of Copper from the World’s Healthiest Foods

What can copper-rich foods do for you?

• Reduce tissue damage caused by free radicals

• Maintain the health of your bones and connective tissues

• Keep your thyroid gland functioning normally

• Help your body utilize iron

• Preserve your nerves’ myelin sheath

What events can indicate a need for more copper-rich foods?

• Blood vessels that rupture easily

• Bone and joint problems

• Elevated LDL and reduced HDL levels

• Frequent infections

• Iron deficiency anemia

• Loss of hair or skin color

Foods that require long-term cooking can have their copper content substantially reduced; for example, cooking beans may result in them losing one-half of their copper content. The processing of whole grains can also dramatically reduce copper content. In wheat, for example, the refining of the whole grain into 66% extraction wheat flour results in a drop of about 70% in the original copper that was present. Cooking with copper cookware increases the copper content of foods.

In 2000, the Institute of Medicine issued new Adequate Intake (AI) levels for copper for infants up to 1 year old and Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) for all people older than 1 year old. The recommendations are as follows:

• 7–12 months: 220 mcg

• 1–3 years: 340 mcg

• 4–8 years: 440 mcg

• 9–13 years: 700 mcg

• 14–18 years: 890 mcg

• 19+ years: 900 mcg

• Pregnant females 14–50 years: 1 mg

• Lactating females 14–50 years: 1.3 mg

The FDA has set the Reference Value for Nutrition Labeling for copper at 2 mg (one mg equals 1,000 mcg). This is the recommended intake value used by the FDA to calculate the %Daily Value for copper that may appear on food labels.

The Institute of Medicine established a Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) for copper that varies by age group: for those 1–8 years it is 1,000 mcg; 9–13 years, 5,000 mcg; 14–18 years, 8,000 mcg; and, 19 years and older, 10,000 mcg.

Copper is an essential trace mineral that is vitally important to health since it is involved in several important enzymatic reactions in the body. It plays such varied roles as promoting collagen maintenance, proper iron absorption and antioxidant activity. Copper is the third most abundant trace mineral in the body. Since many whole, natural foods contain ample amounts of copper, eating a diet rich in the World’s Healthiest Foods can help you to fulfill your daily needs for this important nutrient.

Eating foods rich in copper enhances your body’s usage of this important mineral since these foods naturally contain other nutrients that act in synergy with copper, supporting its physiological function in your body and therefore contributing to your vibrant health.

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) is a copper-dependent enzyme that catalyzes the removal of superoxide radicals from the body. If not eliminated quickly, superoxide radicals cause damage to cell membranes. When copper is not present in sufficient quantities, the activity of SOD is diminished, and the damage to cell membranes caused by superoxide radicals is increased. When functioning in this enzyme, copper works together with the mineral zinc, and it is actually the ratio of copper to zinc, rather than the absolute amount of either mineral alone, that helps this enzyme to function.

Copper also plays a role in many other physiological activities including iron utilization, bone and connective tissue development, energy production, blood clotting, thyroid hormone production, and neurotransmitter synthesis. It also plays a role in maintaining the integrity of the myelin sheath, a covering that protects nerves.

Certain medical conditions including chronic diarrhea, celiac sprue, and Crohn’s disease result in decreased absorption of copper and may increase the risk of developing a copper deficiency. In addition, copper requires sufficient stomach acid for absorption, so if you consume antacids regularly, you may increase your risk of developing a copper deficiency. Inadequate copper status is also observed in children with low protein status and infants fed only cow’s milk without supplemental copper.

Because copper is involved in many functions of the body, copper deficiency produces an extensive range of symptoms. These symptoms include iron deficiency anemia, ruptured blood vessels, osteoporosis, joint problems, brain disturbances, elevated LDL cholesterol, reduced HDL cholesterol, increased susceptibility to infection due to poor immune function, loss of pigment in the hair and skin, weakness, fatigue, breathing difficulties, skin sores, poor thyroid function, and irregular heart beat.

In recent years, nutritionists have been more concerned about copper toxicity than copper deficiency. One partial explanation for this involves the increase in the amount of copper found in drinking water due to the switch in most areas of the country from galvanized (steel) water pipes to copper water pipes. Excessive intake of copper can cause abdominal pain and cramps, nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, and liver damage.

Postpartum depression has also been linked to high levels of copper. This is because copper concentrations increase throughout pregnancy to approximately twice the normal values, and it may take up to three months after delivery for copper concentrations to normalize.

The toxic effects of high tissue levels of copper are seen in patients with Wilson’s disease, a genetic disorder characterized by copper accumulation in various organs. The treatment of Wilson’s disease involves avoidance of foods and supplements rich in copper and drug treatment with chelating agents that remove the excess copper from the body.

The Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) for copper varies by age group: for those 1–8 years it is 1,000 mcg; 9–13 years, 5,000 mcg; 14–18 years, 8,000 mcg; and,19 years and older, 10,000 mcg.

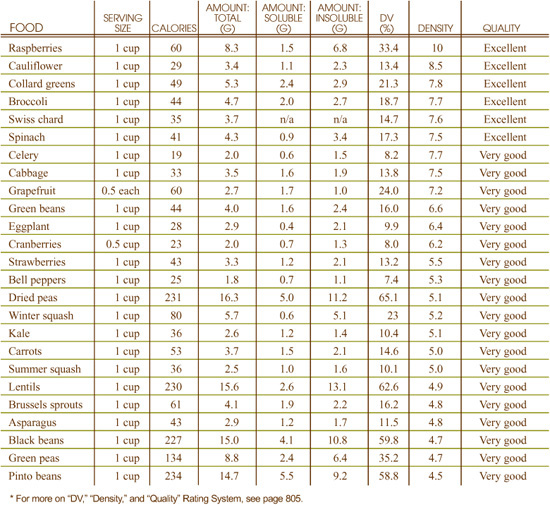

Best Sources of Dietary Fiber from the World’s Healthiest Foods

What can fiber-rich foods do for you?

• Support bowel regularity

• Help maintain normal cholesterol levels

• Help maintain normal blood sugar levels

• Help keep unwanted pounds off

What events can indicate a need for more fiber-rich foods?

• Constipation

• Hemorrhoids

• High blood sugar levels

• High cholesterol levels

Many whole foods contain five or more grams of fiber per serving, and in their whole, unprocessed form, would be highly supportive of health. When foods are processed, however, most or all of this fiber is usually lost. For example, most breads sold in the United States use an extraction process whereby the grain’s germ and bran, the components that contain most of its fiber, are discarded. While fruits and vegetables in their natural state are rich in fiber, the juicing process creates a food product with virtually no fiber. Cooking does not affect the dietary fiber content of the food.

In 2002, the Institute of Medicine at the National Academy of Sciences issued Adequate Intake (AI) levels for dietary fiber. The recommendations are as follows:

• 1–3 years: 19 g

• 4–8 years: 25 g

• Males 9–13 years: 31 g

• Males 51+ years: 30 g

• Females 9–13 years: 26 g

• Females 14–18 years: 26 g

• Females 19–50 years: 25 g

• Females 51+ years: 21 g

• Pregnant women: 28 g

• Lactating women: 29 g

The FDA has set the Reference Value for Nutrition Labeling for dietary fiber at 25 g. This is the recommended intake value used by the FDA to calculate the %Daily Value for dietary fiber that may appear on food labels.

The Institute of Medicine did not establish a Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) for dietary fiber.

Dietary fiber is undoubtedly one of the most talked about nutrients for health promotion and disease prevention. Promoting digestive health, keeping cholesterol levels in check, and filling you up to prevent your waistline from filling out are just some of its numerous benefits.

Processed refined foods are lacking in fiber, and therefore those who follow the average American diet receive less than the amount recommended to promote optimal health and ward off diseases. Yet, whole unrefined plant-based foods are naturally rich in fiber—yet another way eating the World’s Healthiest Foods helps to keep you healthy.

Fiber has been generally classified as soluble (the type found concentrated in oat bran and barley, which is known to reduce blood cholesterol levels and reduce blood sugar) and insoluble (found in wheat, and legumes, whose function includes promoting bowel regularity). Most whole foods contain both types of fiber; however, there may be a much greater amount of one than the other. Recently, medical and nutrition experts proposed that instead of soluble and insoluble, fiber should be classified according to whether it is viscous or fermentable, as they contend that the original terms do not adequately describe the physiological effects of all the different types of fiber. Categories of fiber include: celluloses, hemicelluloses, polyfructoses, gums, mucilages, pectins, lignins and resistant starches.

Certain types of fiber are referred to as insoluble fibers because the “friendly” bacteria that live in the large intestine can ferment them. The fermentation of dietary fiber in the large intestine (colon) produces a short-chain fatty acid called butyric acid, which serves as the primary fuel for the cells of the large intestines and helps maintain the health and integrity of the colon.

In addition to producing necessary short-chain fatty acids, these bacteria play an important role in the immune system by preventing pathogenic (disease-causing) bacteria from surviving in the intestinal tract. As is the case with insoluble fiber, fibers that are not fermentable in the large intestine help maintain bowel regularity by increasing the bulk of the feces and decreasing the transit time of fecal matter through the intestines. Bowel regularity is associated with a decreased risk for colon cancer and hemorrhoids.

Two other short-chain fatty acids produced during fiber fermentation, propionic and acetic acid, are used as fuel by the cells of the liver and muscles. In addition, propionic acid may be responsible, at least in part, for the cholesterol-lowering properties of fiber.

Soluble fibers lower serum cholesterol by reducing the absorption of dietary cholesterol. In addition, they combine with bile acids, which are made from cholesterol, and remove them from circulation. As a result, the liver must use additional cholesterol to manufacture new bile acids. Soluble fiber may also reduce the amount of cholesterol manufactured by the liver.

Soluble fibers also help normalize blood glucose levels by slowing the rate at which food leaves the stomach and by delaying the absorption of glucose following a meal. They also enhance insulin sensitivity. As a result, high intake of soluble fiber plays a role in the prevention and treatment of Type 2 diabetes. In addition, by slowing the rate at which food leaves the stomach, they promote a sense of satiety, or fullness, after a meal, which can help to prevent overeating and weight gain.

Inadequate chewing can prevent the health benefits of fiber from being realized, since insolube fibers, such as lignins, celluloses, and some hemicelluloses, require extra chewing in order to participate in biochemical processes.

There is no identifiable, isolated deficiency disease caused by lack of fiber in the diet. However, research clearly indicates that low intake of dietary fiber (less than 20 grams per day) over the course of a lifetime is associated with development of numerous health problems including constipation, hemorrhoids, colon cancer, obesity and elevated cholesterol levels.

Intake of dietary fiber in excess of 50 grams per day may cause an intestinal obstruction in susceptible individuals. In most individuals, however, this amount of fiber will improve, rather than compromise, bowel health. Excessive intake of fiber can also cause a fluid imbalance, leading to dehydration. Individuals who decide to suddenly double or triple their fiber intake are often advised to double or triple their water intake for this reason. But an even better approach is to increase fiber intake more gradually, in the range of 50% increases over a period of time long enough for the body to naturally adjust. In addition, excessive intake of soluble fiber, typically in supplemental form, may lead to mineral deficiencies by reducing the absorption or increasing the excretion of minerals.

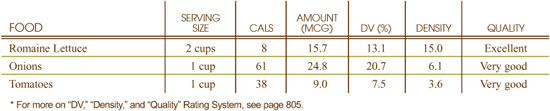

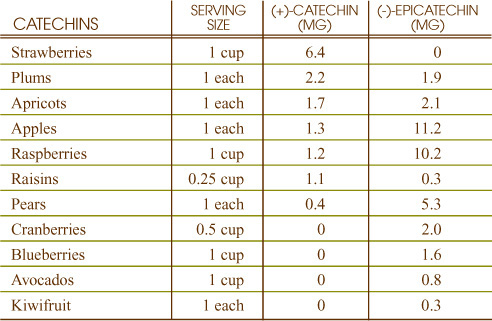

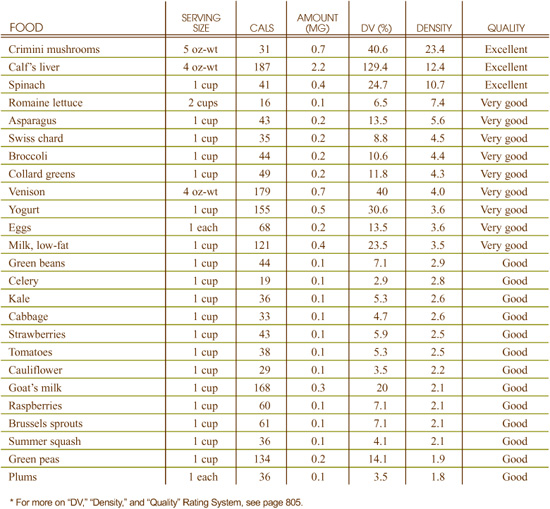

Best Sources of Flavonoids from the World’s Healthiest Foods

What can flavonoid-rich foods do for you?

• Help protect integrity of your blood vessels

• Protect cells from free radical damage

• Prevent excessive inflammation throughout your body

• Enhance the power of your vitamin C

What events can indicate a need for more flavonoid-rich foods?

• Easy bruising

• Excessive swelling after injury

• Frequent colds or infections

• Frequent nose bleeds

• Low intake of fruits and vegetables

Heat, degree of acidity (pH), and degree of processing can have a dramatic impact on the flavonoid content of food. Overcooking of vegetables has particularly problematic effects on this category of nutrients. For example, in fresh cut spinach, boiling extracts 50% of the total flavonoid content. With onions, boiling removes about 30% of the flavonoids.

In addition to the heat, the amount of cooking water may also play a role in flavonoid loss. A study found that zucchini, beans and carrots cooked with less water had higher polyphenolic flavonoid content than those cooked with larger volumes of water. Therefore, quick cooking methods that use little water such as steaming may be of benefit to conserving maximum amounts of flavonoids.

While flavonoids have been gaining recent attention for their health-promoting properties, currently no public health recommendations, such as Daily Reference Intakes or Daily Values, have been established for these phytonutrients.

Flavonoids, an amazing array of over 6,000 different substances found in virtually all plants, are responsible for many of the plant colors that dazzle us with their brilliant shades of yellow, orange, and red. Classified as plant pigments, flavonoids were discovered in 1938 when a Hungarian scientist named Albert Szent-Gyorgyi used the term “vitamin P” to describe them.

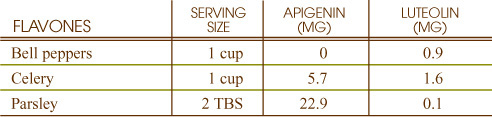

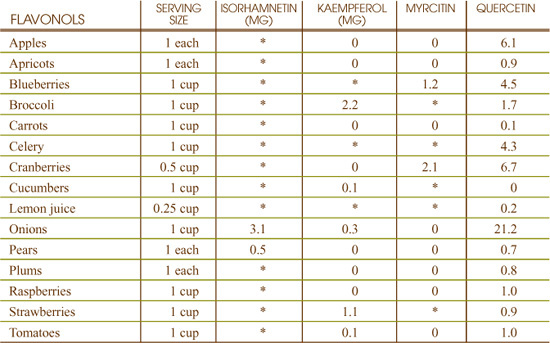

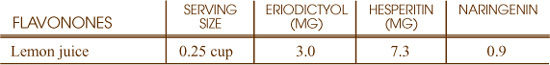

Well-known flavonoids include the flavonols, quercetin, myricitin and kaempferol and the flavones, apigenin and luteolin. Flavonoids may also be named directly after the unique plant that contains them. Ginkgetin is a flavonoid from the ginkgo tree, and tangeretin is a flavonoid from the tangerine.

Flavonoid-rich foods are oftentimes foods that are also rich in vitamin C, which is important since these nutrients need each other to perform effectively. Recent findings that foods as diverse as apples, onions, berries, thyme, berries, tea and red wine had immense health-promoting activities led researchers to discover that many of their benefits may come from their flavonoids.

Most flavonoids function in the human body as antioxidants. In this capacity, they help neutralize overly reactive oxygen-containing molecules and prevent them from damaging parts of cells. Particularly in traditional Chinese medicine, plant flavonoids have been used for centuries in conjunction with their antioxidant, protective properties. While flavonoids may exert their cell structure protection through a variety of mechanisms, as suggested by various research studies, one of their potent effects may be through their ability to increase levels of the powerful antioxidant glutathione.

Inflammation—the body’s natural response to danger or damage—must always be carefully regulated to prevent overactivation of the immune system and unwanted immune response. Many types of cells involved with the immune system have been shown to alter their behavior in the presence of flavonoids. Prevention of excessive inflammation appears to be a key role that many different chemical categories of flavonoids play.

Present-day research has clearly documented the synergistic (mutually beneficial) relationship between flavonoids and vitamin C. Many of the vitamin-related functions of vitamin C also appear to require the presence of flavonoids, as each substance improves the antioxidant activity of the other.

Test tube studies have found that several flavonoids have antimicrobial activity. For example, myricitin has been found to stop the growth of certain strains of Staphylococcus and Klebsiella bacterium while procyanin C-1 has been found to inhibit the growth of HSV-1 (herpes simplex virus).

Poor intake of fruits and vegetables—or routine intake of highly processed fruits and vegetables, whether they be overcooked or juiced—are common contributing factors to flavonoid deficiency.

Potential indicators of flavonoid deficiency include excessive bruising, nosebleeds, swelling after injury, and hemorrhoids. Generally weakened immune function, as evidenced by frequent colds or infections, can also be a sign of inadequate dietary intake of flavonoids.

Even in very high amounts (for example, 140 grams per day), flavonoids do not appear to cause unwanted side effects. Even when raised to the level of 10% of total caloric intake, flavonoid supplementation has been shown to be non-toxic. Studies during pregnancy have also failed to show problems with high-level intake of dietary flavonoids.

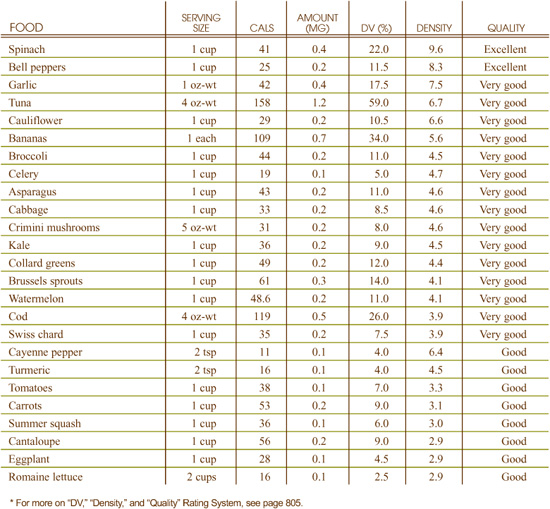

Best Sources of Folate from the World’s Healthiest Foods

What can folate-rich foods do for you?

• Support red blood cell production and help prevent anemia

• Help prevent homocysteine build-up

• Support cell production, especially skin cells

• Allow nerves to function properly

What events can indicate a need for more folate-rich foods?

• Depression; irritability

• Mental fatigue, forgetfulness, or confusion

• Insomnia

• General or muscular fatigue

• Gingivitis or periodontal disease

Folate contained in animal products appears to be relatively stable to cooking, unlike folate in plant products, up to 40% of which can be lost from cooking. (In general, however, animal products only tend to average about 10 micrograms of folate per 6-ounce serving. Calf’s liver is an important exception, with over 1,000 micrograms in 6 ounces). Processed grains and flours may have lost up to 70% of their folate; although some manufacturers add folate back to their processed grain product, this is a voluntary procedure, and there are no standards for this process.

In 1998, the Institute of Medicine at the National Academy of Sciences issued new Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) for folate. The recommendations are as follows:

• 6–12 months: 80 mcg

• 1–3 years: 150 mcg

• 4–8 years: 200 mcg

• 9–13 years: 300 mcg

• 14+ years: 400 mcg

• Pregnant females: 600 mcg

• Lactating females: 500 mcg

The FDA has set the Reference Value for Nutrition Labeling for folate at 400 mcg. This is the recommended intake value used by the FDA to calculate the %Daily Value for folate that may appear on food labels.

Details of folate’s Tolerable Upper Intake Levels (UL) are provided under the heading “Can You Consume Too Much Folate?”

Folate is a B-complex vitamin most publicized for its importance in pregnancy and prevention of birth defects. The term “folic acid” is sometimes used interchangeably with the term “folate.” Folic acid is the form of folate that is generally available in supplements and fortified foods. In food, as well as in the body, this vitamin is usually found in its folate form.’ In the past few years, it has also gained recognition for the important role it plays in promoting heart health. Its name is derived from the Latin word for “foliage,” reflecting its concentration in many leafy green vegetables.