This book began with portraits and the famous portrait ascribed to Andy Warhol, in 1966, by Gretchen Berg, who located everything there is to know about Andy Warhol on the two dimensional surface of his paintings, films and his one dimensional self. Warhol’s work Silver Clouds is mentioned more than once in that interview, explicitly as sculpture, but, in adding sculpture to the list of those surfaces that define him, it has been my hope that this book has added another dimension to this portrait of Andy Warhol and his work. If this book qualifies the attention that has been paid to Warhol’s painting by looking at his sculpture, it does so, not to produce another Warhol, but to deepen our understanding of the Warhol that already exists. Yet, at the same time, and as I will explore in this conclusion, this understanding has no less to do with surface.

Such an understanding of Warhol’s practice is, therefore, three- dimensional in terms beyond those which distinguish sculpture from painting. The third dimension, here, relates to the quality of Warhol’s work being between things: between the physical properties of the work and the readings ascribed by the spectator. It is a concern for surface, but here the surface is felt between the surfaces of matter and thought, between the contours of history. It is defined by virtue of its ability to hold the formally two-dimensional and three-dimensional together, and develop a register between the material and immaterial, illusion and reality.

This polymorphic surface coincides with the idea of post-modern image culture and its scale-less, object-less economy of exchange and equivalence, an idea that, indeed, is important in theoretical understandings of Warhol’s art and personhood. The one-dimensional Warhol is a figure akin to that assimilated subject described in Herbert Marcuse’s book: One-Dimensional Man: Studies in the Ideology of Advanced Industrial Society (1964). Yet, the picture of the world so important to the readings in this book is different to that in which we find Marcuse’s subject. Crucially, for my readings the artworld does not represent that ‘oppositional, alien, and transcendent’ alternative dimension of reality that Marcuse describes of high art, but only an extension of the social world, an elite territorial outpost, metaphysically altered but not by any means offering an alternative to social order.1 It is precisely these conditions that require us to consider Warhol’s three-dimensionality as a surface, and as a between space, rather than a transcendental alternative. Warhol, in three-dimensions, refuses to present either any other reality, or something that might function as a fixable, tangible alternative to the status quo. Instead, his work defended a form of social representation posed in opposition to the artworld’s idealism.

As I have discussed in this book, with the emergence of influential positions such as those taken by Arthur Danto and Donald Judd in the 1960s, this form of idealism took the shape of discourses that attempted to bracket illusionistic space and pose a rarefied form of reality against the territories of ambiguity and relative value outside of the museum. It is precisely amongst these territories, however, and in opposition to these discourses, that Warhol’s surface operates. If post-modern visual culture jettisons scale, the positivist object and the ‘specificity’ of its materials and medium, these are characteristic concerns of Minimalism. Yet I have argued in this book that the dichotomy that considers Warhol’s work as seamlessly assimilated to postmodern image culture on one side, and positions Minimalism on the other, or else reads Warhol as following in the footsteps of Minimalism’s innovations, is contrived for the benefit of historical narrative. By extending his work beyond a notional and defined objecthood, Warhol cast viewer-space in illusory environments that reflected how class registered through the conditions of vision, even in the arena of a putative ‘real space’.

This book began with a comparison between the three-dimensional, ghostly presence of the ‘factory fresh’ Campbell’s Soup Cans (1962) and what I described as the ‘sculptural’ condition of Torn Campbell’s Soup Can (1962). Leaning on readings by Benjamin Buchloh and Roland Barthes, the ‘clean’ works, I argued, substitute the relationship between the painting and its viewer for a single, hovering sublation of the two in the commodity image. In contrast, I posed sculpture as the category defined by a materiality incommensurate with the conditions of the commodity, and thus the appropriate category through which to view the Torn paintings. They, and sculpture in this sense, signify a fall from circulation and a loss of value. Yet it was the sense of an uncanny presence, like that of the ‘clean’ Campbell’s Soup Can paintings, that first brought Warhol to experiment, in the same year, with sculpture in actuality, in the form of Campbell’s Soup Box (plate 2.1). This was a painting-object, or image-sculpture, whereby the repeated Campbell’s painting was transferred onto the three dimensions of a plywood box. This work failed, Warhol claimed, but it led to the total immersive environment of The Personality of the Artist installation in 1964.

Suggested by the examples above is an idea of sculpture in pursuit of a three-dimensional presence already established by the commodity image, rather than three-dimensionality as necessarily a result of sculpture.2 New grounds for sculpture emerge here, while at the same time those conditions traditionally associated with sculpture have served to stand for the fall-out from commodity aesthetics. In the examples of more recent work, images become sculptural objects when printers snarl up, when circulation is impeded. Seth Price’s dispersed Mylar image rolls and Wolfgang Tillmans’ Lighters, like Warhol’s Abstract Sculpture, Crushed Newspaper and his early Crumpled Paper Show, is work that has fallen out of, and become incompatible with, prescribed frameworks for, and assumptions about, image display and relay.

In the work of the other artists that I have related to my discussion of Warhol in this book there is a more general sense of fluidity that, likewise, contours the surface between embodied space and representation. It speaks, for example, of the transitions in Camille Henrot’s work from the museum to the gallery, through images on eBay and the internet. It speaks, also, of the work of Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat, who developed new iconology and a new image-ground on the surfaces of a crumbling New York City. And it speaks of the work of Paul Thek, who filled mock-Minimal incantations of modern life with life-like waxworks of rotting hunks of flesh. But, mostly, it speaks of Warhol and his persistent suggestion that the image is never not in real space and real space is never not an imaging environment. Warhol’s work was the work of re-presentation, whereby social context became aesthetic content and the aesthetic content became the social context. Instead of creating an illusory plane of reality, in which subject and object registered perfectly, Warhol brought the two dimensions of the social viewer and the aesthetic object into the space of mis-registration between them, causing collapse, ambiguity and trespass.

In introducing Warhol’s sculpture and the undertaking of this book, I described sculpture for Warhol, and readings of Warhol, as off-register. Indeed, the off-register, I argued, is something pervasive and fundamental to all Warhol’s work, not just sculpture’s relation to the existing discourse on Warhol in art history. But if the idea of Warhol’s sculpture, understood in terms of its position outside established frameworks of understanding, is easy to get to grips with, an idea of the off-register in itself, and what that means for Warhol’s art, is harder to fathom. If to register is to ascertain something, to form a correlation, the off-register is a mark of dislocation and expresses uncertainty; deviance more often than not in the case of Warhol’s work. Yet, no less than registration, the off-register suggests presence, and though, in itself, says ‘nothing’, means nothing, it stages where meaning occurs.

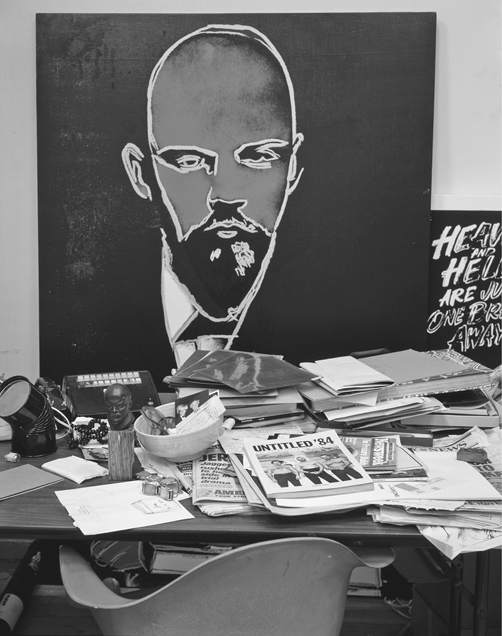

This is how we might also understand Warhol’s three-dimensional surface as it looms above the paintings and commands object-space in the sculptures and installations. The surface of Warhol’s art, described at the start of this conclusion, is a stage of encounter between the sign and the signified; between the subject and the world around it. Yet, though this surface reaches across media and is fundamental to Warhol’s operations, it is also something the study of Warhol’s relation to sculpture especially helps to make clear. I want to now develop this constellation of ideas, of surface and staging, that bear on the off-register, and consider sculpture’s place in relation to three last scenarios in which we find Warhol’s work. The first is Evelyn Hofer’s photographs of Warhol’s studio taken immediately after his death (fig. 6.1 and plate 6.1). In these, we find two works belonging to two late series, The Last Supper and Lenin, which we find each have sculptural counter parts. The second scenario is an interview with Warhol’s assistant Ronnie Cutrone in which Cutrone discusses the source material used for Warhol’s Hammer and Sickle (1976). The third and final scenario is the essay ‘Theatrum Philosophicum’ (1970), by Michel Foucault. Here, Foucault discusses Warhol’s work and, in relation to it, proposes the theoretical model of the ‘phantasm’ which, finally, I shall read my understanding of Warhol’s three-dimensionality through.

***

If, as I have described of Warhol’s paintings, object presence haunts image space, the sense of work in progress in Hofer’s photographs is that of life pervading the space of the dead. Warhol’s beautiful, grand studio was busy right up until the last days. It is a room with areas of clutter rather than a cluttered room, and, generally, there is a sense of knowing where things are put and of organization. In it, a variety of different artistic projects seem to be in progress all at the same time. Amongst the recent work set against the walls of the studio are the two works I shall go on to discuss. They form a backdrop before which are signs of Warhol’s interests and concerns at the sides, on the floor and other surfaces, while papers and acetates are dotted here and there in the clear space in the centre. Warhol had been lifting weights with Jean-Michel Basquiat, there are two weight benches in the studio and a ‘Computrim 900’ exercise bike; there are books on astrology and tarot; there is, on the right, a huge statue; there are shopping bags; and there are boxes, tons and tons of boxes.

The image of Lenin (fig. 6.1) is based on an early photograph of the revolutionary from 1897, which was cropped for Stalin’s purposes in 1948. But this is not the only source material Warhol used for this work, he also consulted a small statuette of Lenin, which we see in the photograph left beside the Lenin painting. The tiny sculptural Lenin is a later portrait than the 1897 one used for the image: the head is bowed, the features now heavily set. Warhol did not photograph this object for the silkscreen. It is difficult to see how this later, small, monochrome, three-dimensional rendering of Lenin informed the final work: it surely would only have complicated the issue of likeness: it is unlike the image of the youthful Lenin. Yet it seems that Warhol worked on the portrait with the statuette as a reference close by. My suggestion is that Warhol invited this unlikely sculpture to sit with the images as a recalcitrant, off-register presence, as something to complicate the picture; to intervene and bring contingency to precisely that seamless process of duplication so often associated with Warhol’s work.

In the case of the second studio shot (plate 6.1), in which Warhol’s last great series The Last Supper provides the point of focus, there are more details to consider. In The Diaries we learn that, at an early stage of the commission, Warhol went to considerable effort, if not expense, to procure a 3D model of Leonardo’s famous design:

Thursday, April 25th, 1985.

I’m trying to find another store that sells the sculpture of the Last Supper that’s about one-and-a-half feet—they’re selling it in one of those import stores on Fifth near Lord & Taylor but it’s so expensive there, about $2,500. So I’m trying to find it cheaper in Times Square. I’m doing the Last Supper for Iolas. For Lucio Amelio I’m doing the Volcanoes. So I guess I’m a commercial artist. I guess that’s the score.

Tuesday, July 9, 1985.

Sent Benjamin out on a simple errand and it cost me a thousand dollars! I’d given him $2,000 to go get the large-size sculpture of the Last Supper that we’d bargained the guy down from $5,000 to $2,000 on. So he went there and it wasn’t there anymore. The Last Supper comes in small, medium, and large. So, then at this other place, I’d gotten the guy down from $2,500 to $1,000 for the medium. But Benjamin forgot we’d gotten them down, and he bought the medium one for $2,000! He didn’t remember! It was actually the size I really wanted, anyway, but he wound up giving the second store for the medium one what he was supposed to buy the large one for. So this means he hasn’t got a head for figures—a thousand dollars is a lot of waste. I just couldn’t believe it, after I’d haggled so hard.3

These diary entries provide the reader with a vivid snapshot: the image of a two dimensional Warhol with which this book began. He self-mockingly admits to being ‘a commercial artist’ and seems to justify the popular critique of himself as cynical and overwhelmingly concerned with money, confirmed by the petty despair at his assistant’s lack of nous. As much as ‘commercialism’ is a contentious issue between Warhol’s detractors and those that come to his defence, it was also a central and generative struggle for Warhol himself. While he devised a practice that was arguably more proximate to commerce than any before, as his Diaries and interviews attest, his own feelings in relation to this fluctuated. He frequently expresses a wish to be seen as avant-garde, or be associated in such a way, and we read his conceding to being a commercial artist in the passage above as indicative of a loss of avant-garde status in this respect. At the same time, however, the period in which he makes The Last Supper was a period in which a new wave of artists harnessed the powers of the entrepreneur, the adman, the stockbroker, and the pop star. So it is perhaps the kind of commercial work that he is engaged with in the case of The Last Supper that causes consternation. The work was a commission by his old acquaintance the gallerist Alexandre Iolas, a person who links Warhol to artists such as Max Ernst and Jean Tinguely. So, in Warhol’s mind, perhaps the commission made him look older than he would like. Or, indeed, perhaps Warhol’s attitude of surrender is a mark of finally leaving these questions behind: for The Last Supper, Warhol worked uninhibited. This, his last major project, comprised over 100 variations and 40 preparatory drawings.

Warhol had only recently undertaken the commission for The Last Supper at the time of the diary entries. The importance of the model, here, is highlighted by the efforts we hear that Warhol undergoes to get it. However, any schematic relationship to the final image is utterly imprecise, it is certainly not the source of the image Warhol reproduced. Warhol used a variety of sources for this work since, according to David Bourdon, reproductions of the original were too dark.4 Instead, Warhol worked from multiple print copies, and another, cheaper, model in white plastic. The different sources used depended on which of the two different painting techniques he used in the series. The works shown at the opening of The Last Supper exhibition, in Milan, in spring 1987, were silkscreened, but, possibly influenced by Jean-Michel Basquiat, Warhol also returned to a variant of his early freehand tracing technique for another series of The Last Supper. These were not included in the Milan exhibition but the painting in the studio photograph is an example of one. In these, the figures are rearranged, with symbols of a later era—brand images and price tags—accompanying it.5

Trying to understand the role of this sculptural source material what seems absurd is the notion of veracity to the original in these negotiations of image and object, copy and master, and painting and sculpture. Having been so damaged and restored so many times, to different degrees of success, Leonardo’s Last Supper is itself no original: the image does not even register with itself. Even so, the high-kitsch porcelain sculpture of Last Supper that Warhol acquired is a kind of obscenity of misregistering values as well as verisimilitude. Yet perhaps difference is again the role sculpture played in the making of this work: it diverts the transition of the image to the canvas through an object that acts in different ways to complicate and intervene in the registration of image-to-image. Sculpture intervenes to ‘stage’ the process of representation. Literally intervening in the space between the artist and the canvas in the studio, its difference and difficulty contributes to the sense of presentness that we also find in the ‘clean’ Campbell’s Soup Cans and, for example, in the Shadows’ invasive and yet negative presence.

This is equally what is at stake in Ronnie Cutrone’s description of the Hammer and Sickle series of paintings. Warhol originally had attempted to make a silkscreen of already existing images of the hammer and sickle symbol but, as Cutrone describes:

the symbols were flat, stencilled. And I thought, well, maybe I could find something that had more depth to it, like an etching or an engraving. But that wasn’t too successful. Then eventually, one of us said, ‘Well, let’s just buy the hammer and sickle and take photos of it.’ […] So I bought them back, cast large shadows on them with side lighting, and shot them. Then we did paintings with a sponge mop—big, white, thickly painted backgrounds—and then we screened over them in red and black or just black. To me, those paintings were successful because they just weren’t very communist; they weren’t so dead-end. There was something architectural and almost semi-abstract about them.’

You mean sculptural?

Actually sculptural is more the word. They looked like they could be an amusement park ride somewhere, in Disneyland even.6

In Cutrone’s account, sculpture’s role is vital. It acts as a force that causes the painting to deviate from a symbol of communism towards abstraction, but at the same time, in its mis-registration, translates that ambiguity powerfully, makes it present. It is a force of differencing and de-familiarisation (and, thinking of Disneyland, perhaps of carnival). Much of Warhol’s work was informed by this sense of something sculptural not necessarily bound to objecthood but, between registers, difference. Perhaps this is why the story of Warhol’s sculpture is also the story of attempts to represent immateriality: the invisible sculptures, shadows and holograms that ironically end up producing a whole slew of matter, of things leftover. The real hammer and sickle, and the Last Supper model and Lenin bust in Hofer’s photograph, are each examples of this matter.7

This sense of sculpture as three-dimensional surface, as presence and as a force of difference that I have been suggesting is, however, nowhere on view in Hofer’s photograph itself. Instead, here is representation that fails to account for difference or allow for mis-registration. Without Warhol, the studio’s clashing registers, its jumble of Jesus, the logo for General Electric and Lenin, reflects misunderstandings of Warhol’s work as a superficial, post-modern hodgepodge.

And so to the final scenario in which we encounter 3D Warhol. Michel Foucault’s 1970 essay ‘Theatrum Philosophicum’, in which Foucault describes exactly this state of apparently empty difference:

of Warhol with his canned foods, senseless accidents, and his series of advertising smiles: the oral and nutritional equivalence of those half-open lips, teeth, tomato sauce, that hygiene based on detergents; the equivalence of death in the cavity of an eviscerated car, at the top of a telephone pole and at the end of a wire, and between the glistening, steel blue arms of the electric chair.8

But does that mean that we find this work arrested in a state of one-dimensional superficiality for Foucault? This is that same idea implied by the words put into Warhol’s mouth in Gretchen Berg’s 1966 article ‘Andy Warhol: My True Story’: ‘If you want to know all about Andy Warhol, just look at the surface: my paintings and my films and me, and there I am.’9 No, though Foucault might have agreed that looking at surfaces is important, he would, however, not have agreed with the suggestion of simplicity, or that these surfaces can be collapsed back into any ‘true story’. Instead, Foucault’s surface acts as an antidote to the idea of Warhol as superficial and this marries it with what I have hoped to present in the previous chapters on Warhol’s sculpture. For Foucault, the enfolding of difference and repetition in Warhol’s work—its ‘stupidity’—has the consequence of releasing meaning from the weave of ‘words and things’, and describes instead what Foucault calls ‘the phantasm’.10 In his description of this concept, Foucault collects many of the ideas that I have used in describing sculpture, and I want to develop this parallel, finally, as it expands on the significance of the three-dimensional for Warhol as something beyond parochial categories pertaining to media.

‘Theatrum Philosophicum’ is ostensibly a review of the writing of Gilles Deleuze. Yet it is also a piece of critical writing that as much advances Foucault’s own thinking as it is a celebratory endorsement of Gilles Deleuze’s project; a project of discovering difference within thought—as a form of free-thought—within its own aesthetic spectrum.11 Foucault reclaims surface as a site of a radical aesthetics through the conception of the ‘phantasm’. The phantasm is thought without object; an unconstellated, surface-thought that, Foucault writes, functions ‘at the limit of bodies; against bodies and protrudes from them’: phantasms ‘topologize the materiality of the body.’12 It is the intermediary surface which thinking breaks when it distinguishes between ideas and materials, images and objects. The phantasm announces the presence of thought without pertaining either to its object or its subject, instead it is paired with the event—what we might understand as the thought-occurrence of phantasmic thinking. This idea of the phantasm, I want to suggest, is what Warhol’s sculpture expresses through the anti-objects, charged spaces and three-dimensional paintings considered in these pages: it is the three-dimensional surface of Warhol’s aesthetic vision. It is ‘atmosphere’. It is the corollary of the ‘eerie concreteness’ Benjamin Buchloh senses in the Campbell’s Soup Can series, and it is the latent sense of presence Danto feels when he sees the spectre of the ‘stock-boy’ in his ruminations on Brillo Boxes. It is newness, ever renewing, ever emerging and continual; it is the thought equivalent of an Invisible Sculpture. These presences animate the surfaces of the works, the spaces of invisibility and installation. Foucault proposes a philosophy that attends to the phantasm and, in coming to regard Warhol’s practice as phantasmic, we have an art form that accompanies this. For Foucault, a force of differencing beams out from Warhol’s repetitions of images, duplications of objects and his perverse, subversive deferral to the logic of categorisation. Warhol’s phantasmic art remains undifferentiated, unconnected, on the surface. Like the phantasm, it is all surface without being two-dimensional. It registers with the three-dimensional presence of the phantasm, not an object in space but an in-between surface on which representation figures.

For Foucault, the phantasm is understood as an alternative to a particular set of discourses that subordinate the surface to underlying structures: neopositivism, phenomenology and the philosophy of history.13 These, Foucault writes, fail to account for the event, for surface. They (respectively) either confuse it with the ‘state of things’ and the object; treat it as only accountable within the framework of subjective meaning; or, lastly, place its ongoing within a structure of past and present. Foucault’s critique correlates with the opposition to temporal, phenomenological and positivist orders in Warhol’s art. It is negative, ambiguous and ever concerned with renewal. Moreover, confirming the parallel between the philosophy of phantasm and Warhol’s art of surface, Foucault’s philosophy of surface, as a critique, maps perfectly onto Warhol’s critical engagement with Minimalism. Foucault’s description of positivism’s substitution of surfaces for depths; the ‘domain of primal significations’ of phenomenology; and the ‘pattern of time’ emergent from the philosophy of history, pertain directly to the ways in which Minimalist art is received. Here the politics of the phantasm extend the parallel with the politics I have argued are at the heart of Warhol’s work. What Foucault does to philosophy, Warhol does to the artworld: undoing its self-image as a place apart from superficiality, embedded in structures organised around social value. Through Foucault’s phantasmic surface, we have a means to think Warhol’s surfaces without jettisoning his criticality, releasing surface from an understanding whereby it only serves to make realisms seem more precious, more valuable.

The importance of the phantasm, then, is that it elucidates a condition that disrupts attempts at disambiguation in response to a larger culture that creates inequality through such intolerance of ambiguity. Through sculpture, we understand the phantasm of Warhol’s art: to encounter it is to feel the resonance of those difficult relations with objecthood that, despite the image plane, linger no less. And the phantasm in turn helps us understand what sculpture meant for Warhol’s work. It intervenes in the spaces of disambiguation, distinction and taste; it trespasses across the boundaries, spatial and discursive, that define them. In its resistance to these means of ascertaining and maintaining value, the phantasm of Warhol’s work takes on a political dimension, a third dimension of surface and perpetual trespass: we should all be strangers in the artworld together, it says.