One of the ideas at the beginning was we knew we wanted to build at least part of the fantasy world because of the rules of how these two worlds collide and integrate. The main concept of the script was the fantasy world is supposed to be scary in certain moments—but it is the world that is the most clear in our young character’s eyes. At the end, in my opinion, the fantasy brings hope into this terrible reality she is living. Somehow she knows the fantasy world was created for her, to save her from that reality. —EUGENIO CABALLERO

PAN’S LABYRINTH BEGINS with a fallen Ofelia, bleeding and breathing hard—but the blood is drawn back into her body, time is flowing backward, back to a fairy-tale legend. As the camera tracks across a seemingly deserted and dark kingdom, a sonorous narrative voice tells a strange tale about a lost princess:

“A long time ago, in the underground realm, where there are no lies or pain, there lived a princess who dreamt of the human world. She dreamt of blue skies, soft breeze, and sunshine. One day, eluding her keepers, the princess escaped. Once outside, the bright sun blinded her and erased her memory. She forgot who she was and where she came from. Her body suffered cold, sickness, and pain. And eventually she died. However, her father, the king, always knew that the princess’s soul would return, perhaps in another body, in another place, at another time. And he would wait for her until he drew his last breath, until the world stopped turning. . . .”1

The little tale is told as the camera tracks across a subterranean kingdom as lonely and quiet as a graveyard at night, save for the shadowy form of the little princess escaping up circular steps to the surface world.

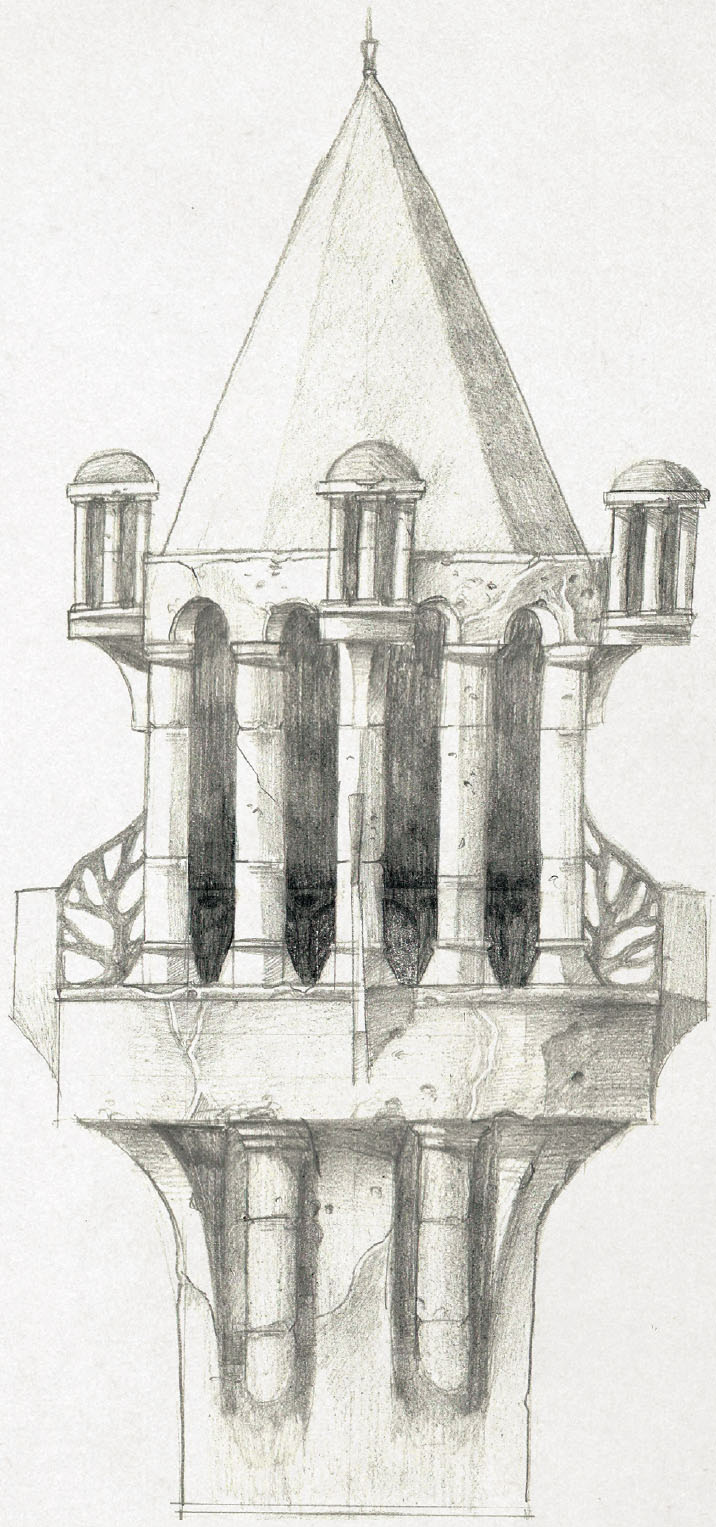

The view of the kingdom was a miniature set created by Spanish special effects master Emilio Ruiz del Río. “I was such a fan of Emilio Ruiz and it was an honor to meet him,” says visual effects supervisor Everett Burrell. “He was famous for his forced-perspective miniatures. He’d build them on shelves and hang them on location, in the foreground, so you’d actually have them instantly composited in-camera. He built this big miniature of the fantasy underground city and we added a little CG girl running around the side of it. They push in and look up and transition into the location that is about a six-hour drive outside Madrid, an old destroyed church we shot in Belchite.”

Underworld kingdom details by Raúl Villares.

The ruins represent the outside world of blinding sunshine and forgetfulness, with a human skull among the rubble bearing mute witness to the devastation in the aftermath of fascism’s victory. The location itself is historic—there, in 1937, Republican and Franco forces clashed in the Battle of Belchite. The town was destroyed, but its ghostly ruins remain as a memorial. Guillermo Navarro recalls they arrived at the location without actors and so early in the production they were practically “off schedule.” The establishing scenes were shot at the end of the day, toward the magic hour when the sun is low to the horizon, and the cinematographer notes that because of the tight budget they didn’t have the resources for a big lighting setup. “That was pretty much natural lighting, so I’m very careful about when to do it,” he says. “It was a very iconic place. It represents the tragedy of the war.”

Ofelia and her mother are introduced as they arrive at the mill. Ofelia, a book lover who brims with imagination and wonder, is an intruder here, a place where magic and wonder do not exist, where one must accept the way things are. Del Toro’s screenplay originally had Ofelia and her mother arrive by train, with Captain Vidal waiting at the station. “The idea was that at the train station you would see a little of the context of the war,” Caballero says. “But it would have been too much concrete information. I think it was a wise decision to take away the train station. It now works like a tale: ‘Once upon a time, in a mill in the middle of a forest . . .’ It’s a better way into the film.”

Sketch of the railway station, a location unused in the final film, by Raúl Villares.

“The mill has been turned into a kind of barracks dominated by men, whose hardness and search for vengeance is embodied by Vidal, the Fascist,” Pilar Revuelta notes. “So it is a cold world, where almost all of the architecture and furniture is made up of straight lines—everything is cutting, rough.”

The props department built a lot of the furniture for the mill, including the work desk and folding bed in Vidal’s quarters, the kitchen table, and the bed where Ofelia and her mother sleep that first night at their new home. For impressionable Ofelia, these and other pieces of furniture were designed and built to convey the mill’s ominous atmosphere. “There were strong pieces made out of very hard, dark wood to give you the sensation, as when you were a child, that everything is looming and out of proportion,” Revuelta says. “The table where the soldiers eat is very big; the bed where the mother sleeps is immense. The whole idea of being out of scale was important to that place.”

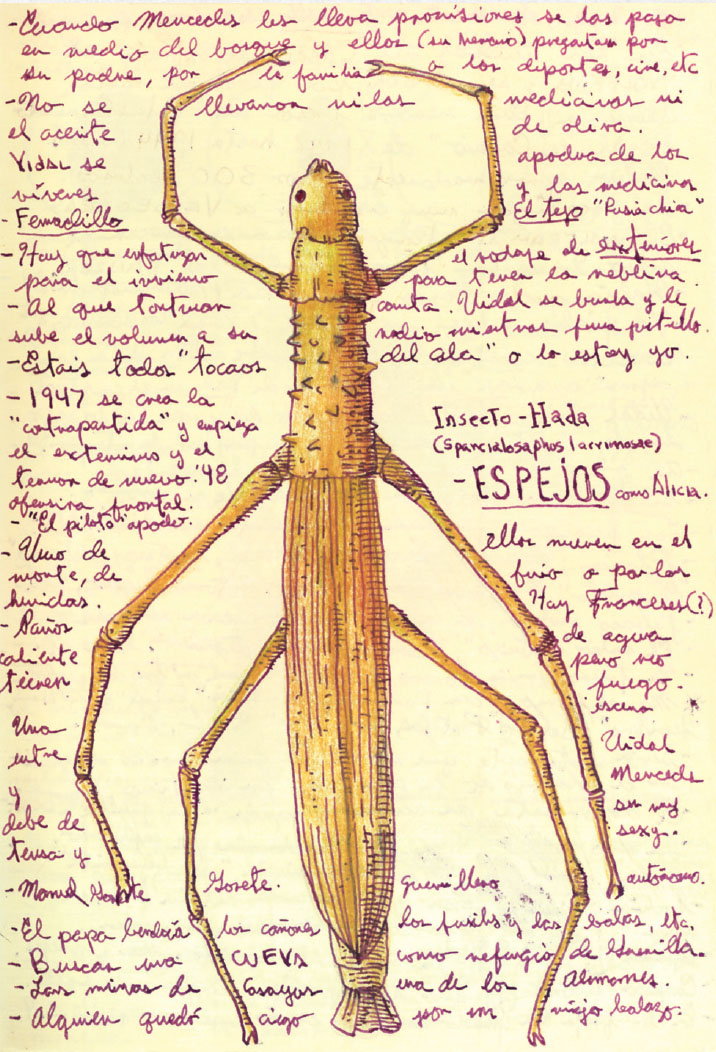

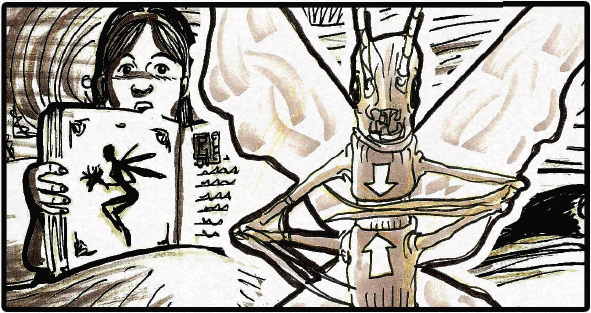

An early depiction of the stick bug from Guillermo del Toro’s personal notebooks.

Because of Carmen’s fragile condition she does not sleep with her new husband, allowing Ofelia to happily curl up in bed beside her. It is here that as her mother drifts off to sleep, Ofelia places her ear to her womb and tells her unborn brother a story of a land of sorrows where each night, upon a dark mountain, a magic rose blooms that will bestow immortality to anyone who plucks it.

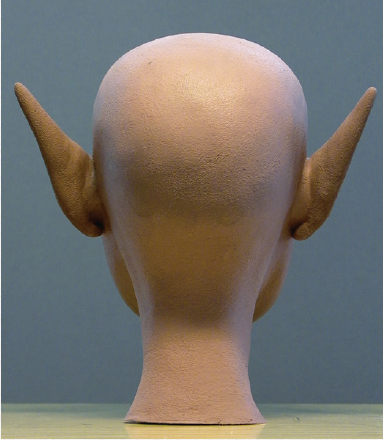

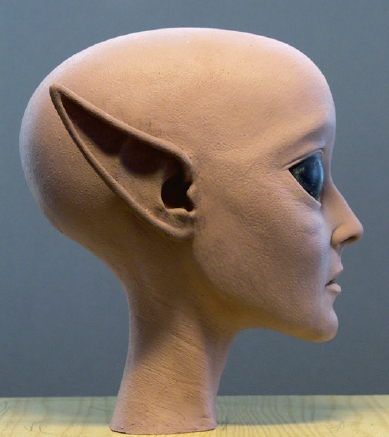

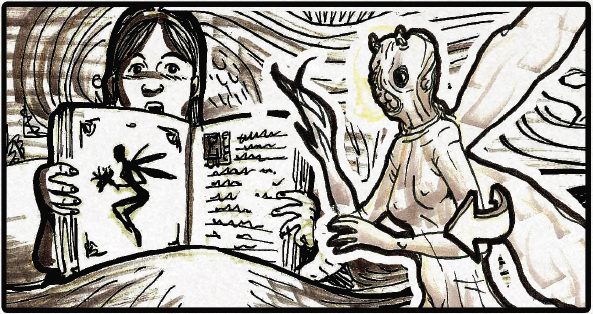

The strange winged stick bug then appears in the bedroom. It sees an illustration of a winged fairy in a book Ofelia has brought to bed and transforms into the storybook image, one of three fairies Ofelia will meet. “Our challenges included bringing some of the characters to life, and the stick figure insect and fairies were our first task,” Burrell explains. “Anything involving CG characters is difficult, because it involves not only modeling but animation. For the stick bug design we used lots of references of leaves and tree bark, to get an organic vibe. As the insect repositions into the fairy, Guillermo wanted it to look painful, with bones cracking—once the transformation is complete, the fairy cracks her neck, a Bruce Lee kung-fu thing. All the fairies are bald because [our ability to create digital hair] wasn’t quite there yet, at least in our budget range. We had just started doing fluid dynamics and hair and fire, and we were prepared to do it, it was just an extra cost. Guillermo said, ‘Fuck it. They’re bald.’”

A model of the stick bug created by DDT. This model would be digitally scanned so that CafeFx could create a CGI version of the creature.

Bald fairy models created by DDT for scanning by CafeFx.

“The fairies were a perfect example of what I mean by managing adversity,” says del Toro. “I saw the design, with and without hair, and thought, They look more insect-like without hair. And voila! Savings and better creatures!”

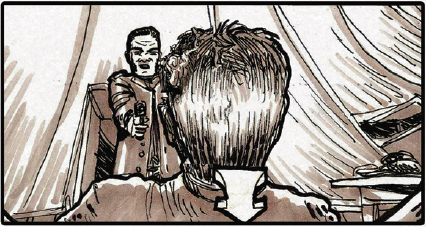

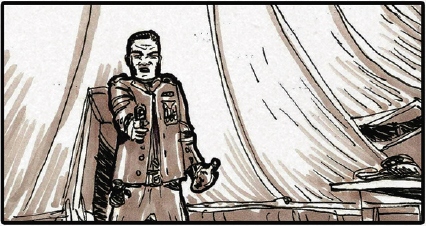

That first night, the brutality of the real world is revealed in a savage scene where Vidal joins the questioning of an older man and his son found wandering the forest. They explain they were hunting wild rabbits, as will be discovered when Vidal thoroughly searches their bag and finds a dead rabbit. But first, without hesitation, Vidal uses a bottle from their bag to bash the younger man’s nose to a flattened and bloody mush, before shooting the father and finishing off the son.

In that horrifying moment the ruthless monster festering inside Vidal’s well-groomed exterior is revealed. Filming the scene was something else, López recalls, and began with the actor who played the victim wearing a prosthetic nose and López wielding a specially constructed bottle, the bottom half of which was made of foam. “This is about precision,” López explains. “I said to Guillermo, ‘Okay, so I’ll hit him in the face and break his nose.’ And Guillermo says, ‘No, no, no! Do it as a game. The goal of the game is to level his face, to leave it completely flattened.’ That gives you an idea of what to do. You’re not just going to kill him; you’re going to leave the protuberance of his nose as if it was a plane. While filming, Guillermo was saying, ‘Harder, hit him harder!’ And we’re two actors and we laugh a bit [between takes]. That’s how it was. It was a lot more fun than the end result on screen—that gives you goose bumps. But Guillermo fills you with information and never leaves you stranded. He never says, ‘Go look for the character.’ He tells you how the character breathes!”

“Guillermo’s directing style starts with his being a people person and an observer who absorbs everything,” says Doug Jones. “I’ve noticed on all the movies I’ve done with him that he directs each actor differently; his voice, his delivery, his demeanor is different. He will find the space we live and communicate in. It’s like he creates a control panel with buttons for every actor, so on set he knows you well enough to press the buttons that work for that scene. With me, the most direction I got on Pan’s Labyrinth was before the movie started. We had lunch one day and he told me to look at barn animals, goats and cows, to see how they move their hind quarters, how their hoofs meet the ground, how they disperse their weight, or shake off flies—it was about the physicality of the Faun.”

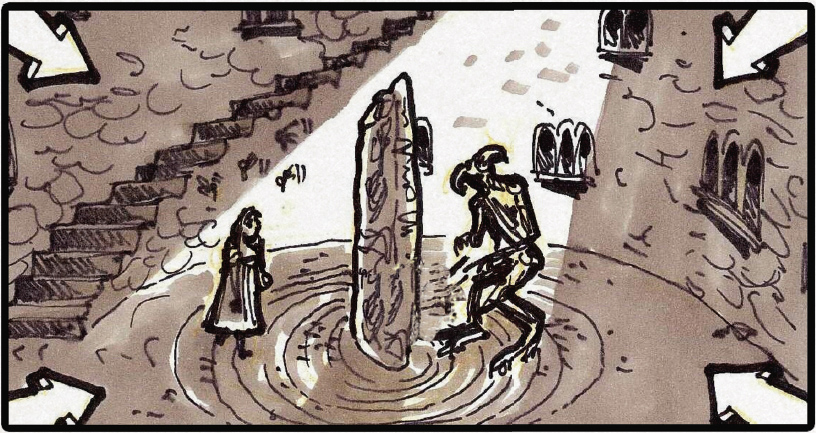

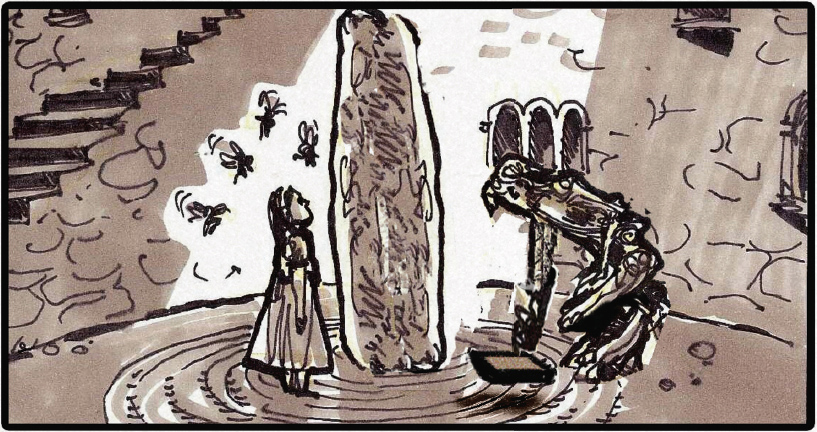

Ofelia enters the labyrinth that first night at the mill, guided by the fairy, and finds a well with steps circling down to a space with a central pillar carved with images of the Faun, the lost Princess Moanna, and a baby. Although the fantasy world rules included warm colors, the labyrinth is seen at night and cinematographer Navarro felt it was “too much of a stretch” to make it warm, so a green-blue palette was used. It became the thematic color scheme for Ofelia and the Faun—later, when the Faun visits Ofelia at the mill one night, the same green-blue effect is used.

In contrast to the storyboards, the final scene was filmed outdoors.

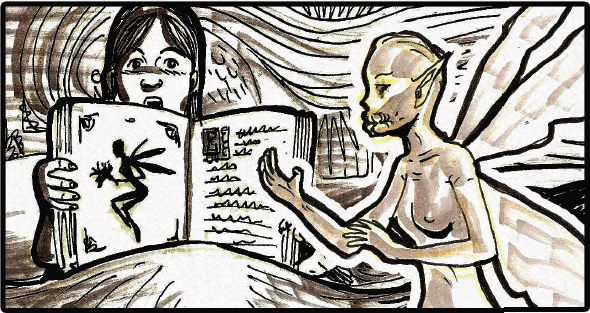

When the old Faun appears, as if awakened from slumber, he tells Ofelia that she is the lost Princess Moanna. Here, deep within the labyrinth, is the last of the portals that were opened by her father to allow her return. But first, before she can go back, she must prove herself. And so the Faun gives her the Book of Crossroads that will instruct her on the three tasks she must successfully complete.

Jones had first been introduced to Ivana Baquero as himself, but because she was so young, it was decided that she should see him getting into the Faun makeup to avoid any potential fear factor. “I was about halfway through the process, where she could still see that tall, skinny guy she had met earlier,” Jones recalls. “And she had this childlike wonder, ‘Oh, my gosh! So that’s how you put that on!’”

“The Faun and the creatures did not frighten me,” says Baquero. “I did my first movie when I was eight and participated in a couple more before Pan’s Labyrinth. They were all genre films, so by then I was used to seeing monsters, prosthetics, and wax bodies. But Doug Jones was unbelievably good! He acted the whole movie in Spanish! And he managed to pull it off so gracefully even after all those hours to get the prosthetics on! I admire him so much.”

Although Spanish actor Pablo Adán dubbed the voice of the Faun in the final film, Jones had insisted on learning and delivering his lines in Spanish. “Doug Jones is just amazing,” del Toro adds. “He delivered above and beyond what he needed to. I was going to allow him to say his lines phonetically, just to sound like the lines. He delivered them in a very heavy American-accented Spanish, but it made his performance more beautiful and powerful.”

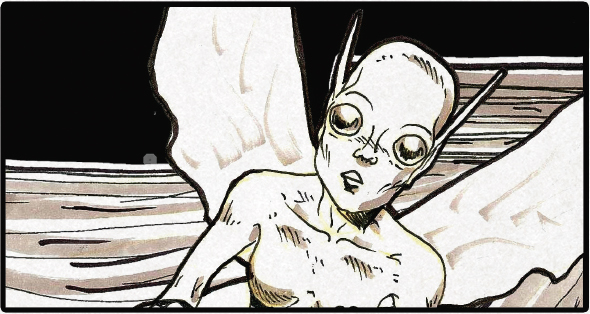

For Jones’s part, the Faun costume and makeup was the most comfortable he ever performed in. “When you’re wearing something from head to toe, that’s a complete transformation of your entire body,” the actor explains. “It often requires many different mechanical bits, buckles and snaps and glue and aesthetic pieces. There’s always something pushing or pinching, and you always come out of it with red marks on you somewhere. That’s just part of the deal. Well, when the Faun makeup came off every day, there were no red marks—nothing! It was the most balanced weight dispersed design I have ever worn. I marvel at DDT. I told them this had never happened to me before and they should be very proud of themselves.

Concept art by Carlos Giménez for the stone steps that lead to the portal.

The Faun is both obsequious and threatening in his interactions with Ofelia.

A page from Guillermo del Toro’s notebooks offers an early interpretation of the Faun.

“But there were challenges, oh my goodness,” Jones adds. “I was up on stilts, I had prosthetic legs zigzagging behind and under my feet. The mask that re-created the top part of the Faun’s face had eyes wider than my own, so I had to look through pinpricks in the tear ducts, which means that I had no peripheral vision, which affects your balance. I would have to clear a path and walk through a couple of times in rehearsals to make sure I had my footing. So, in the film I don’t walk around much. I might take a step or two and plant myself and deliver dialogue. Foam latex covered my ears, and the ram horns on the headpiece is where they hid the batteries and motors that operated the eyebrows, the eyelids, the ears that wiggle. The DDT folks had to puppeteer all that and when they turned it on it it’d go zzzzzzzzz on the top and sides of my head. And some scenes with Ivana we would be close and talking softly in Spanish and I’d be pretending I could hear her. Talk about a challenge! And because of the way the legs were configured, and the little tail sticking out of my butt, I couldn’t sit in a regular chair. My resting place was a bicycle seat contraption with a T-bar that I leaned forward on. When the camera was going it was the most comfortable suit and makeup combination I ever had. But at rest, you couldn’t really be. So it made for very long days. Of course, in the end it was all worth it.”

![]()

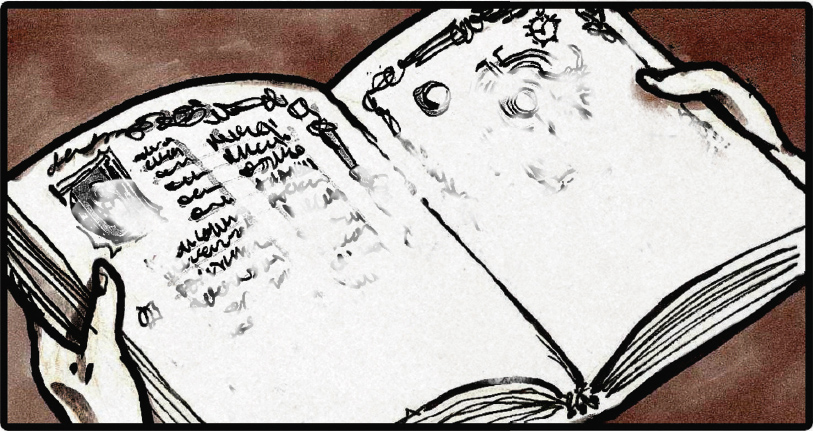

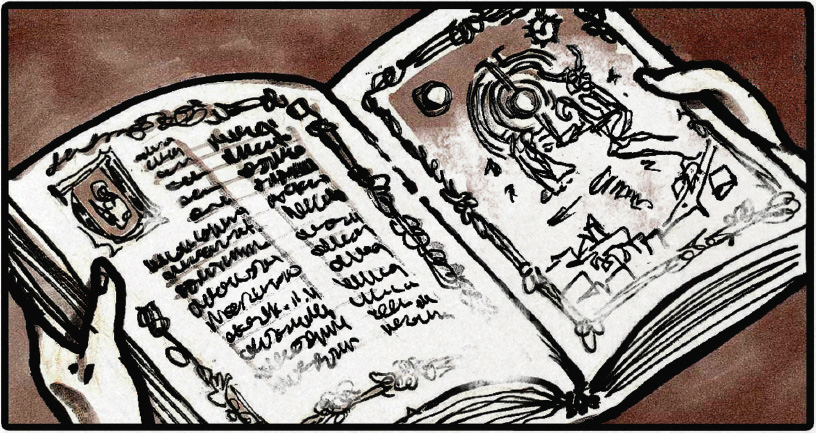

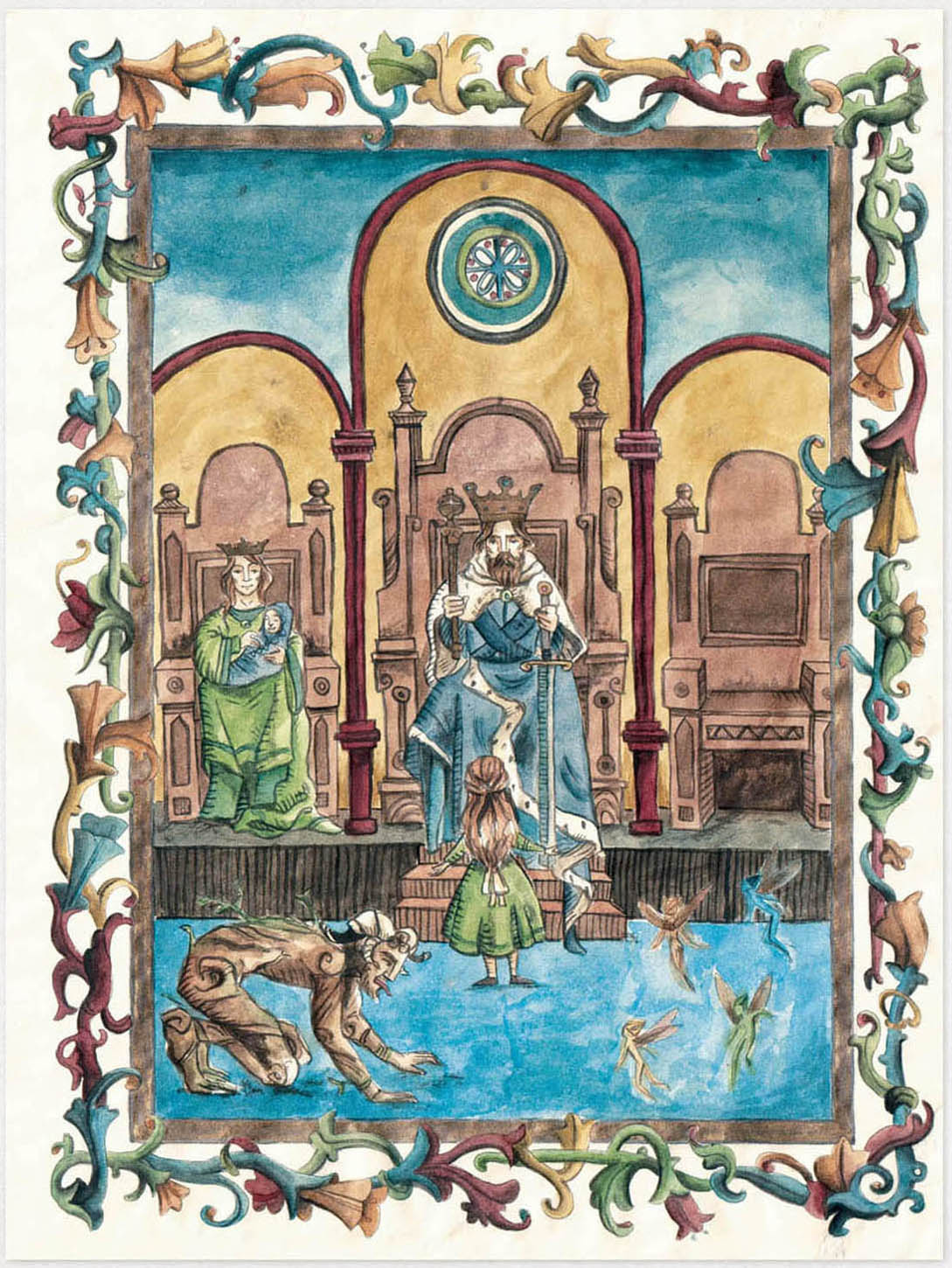

Pages from the Book of Crossroads illustrated by Esther Gili, with calligraphy by Maria Luisa Gili: The princess stands before the king and queen at the end of her quest.

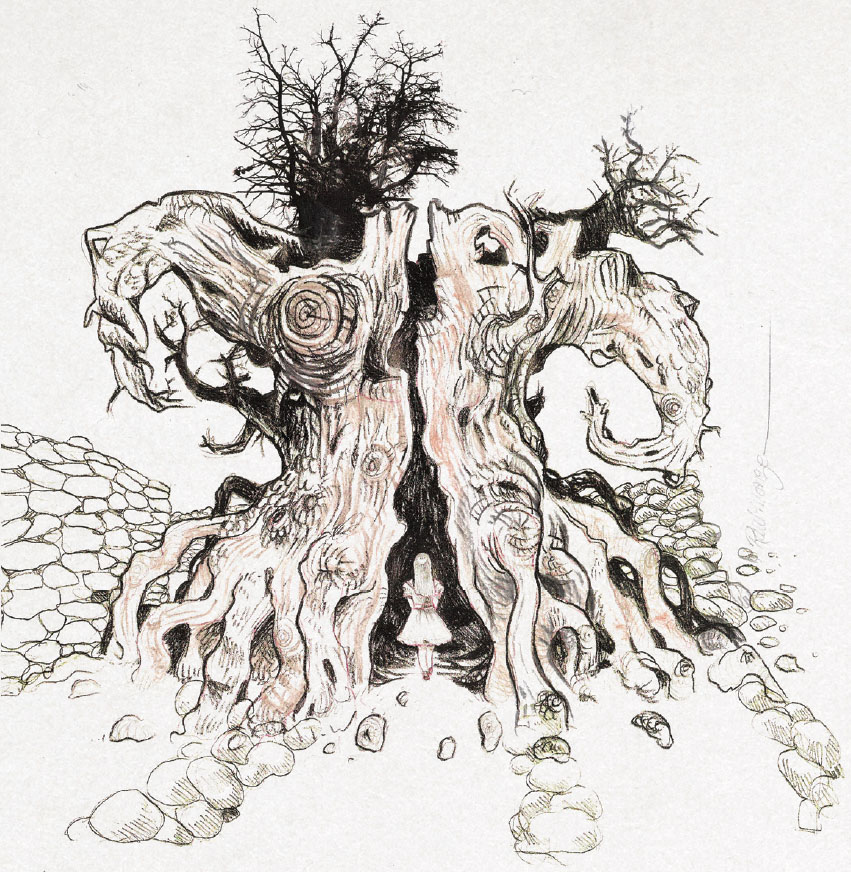

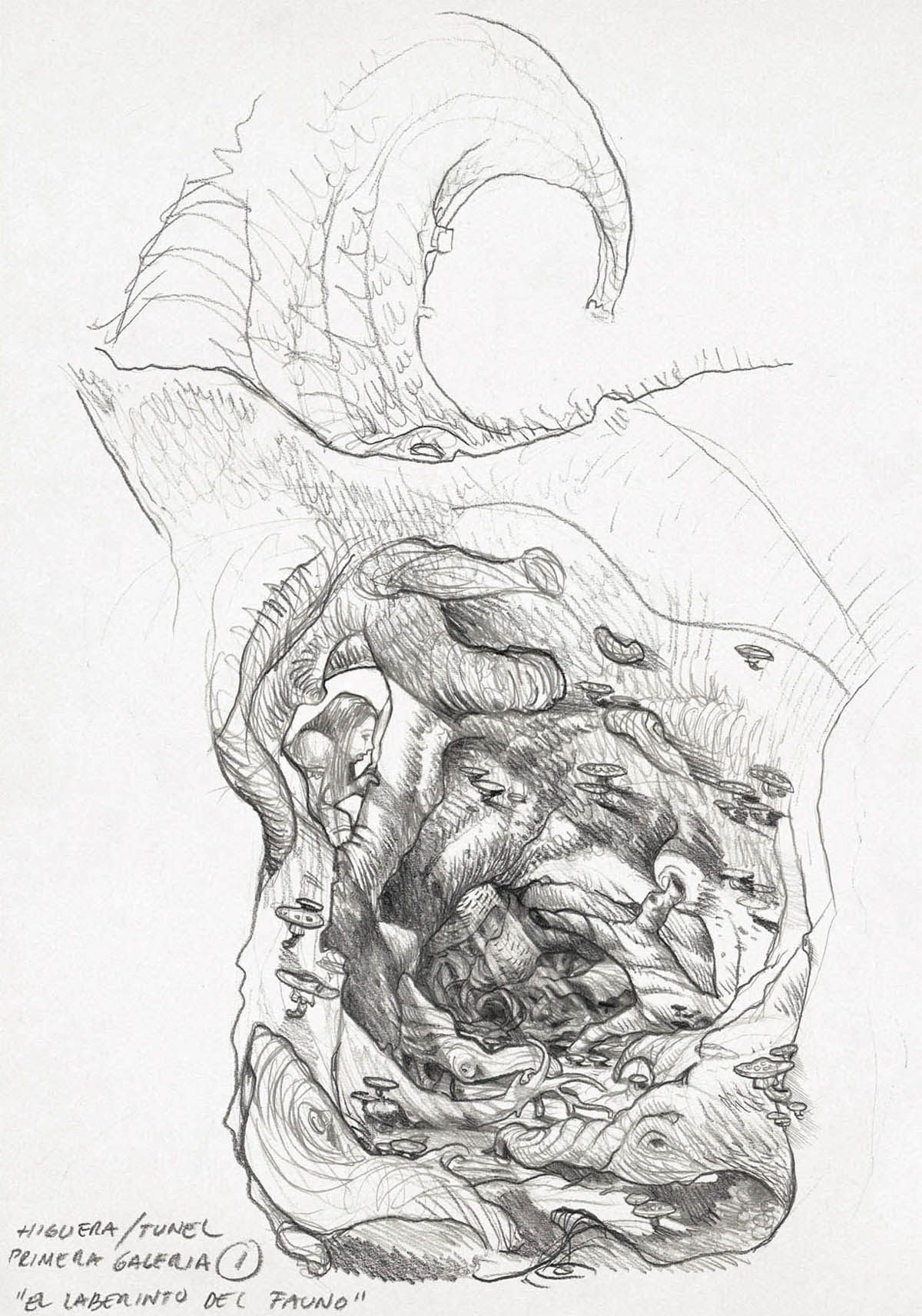

Ofelia’s descent into the fantastical fig tree.

The task and temptation that awaits Ofelia in the Pale Man’s lair.

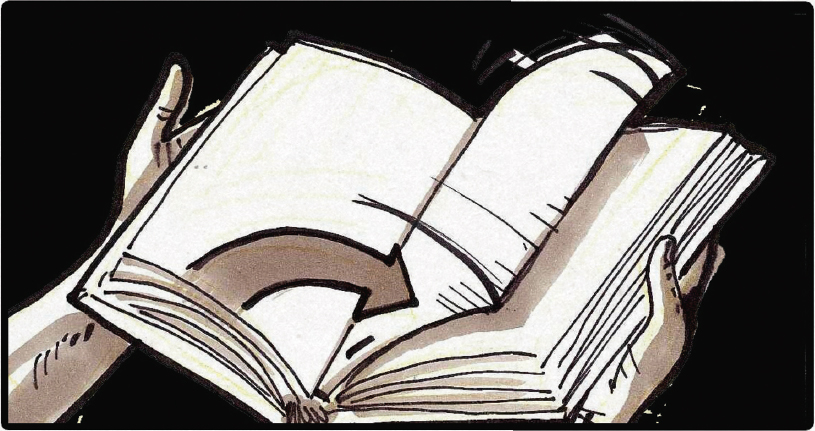

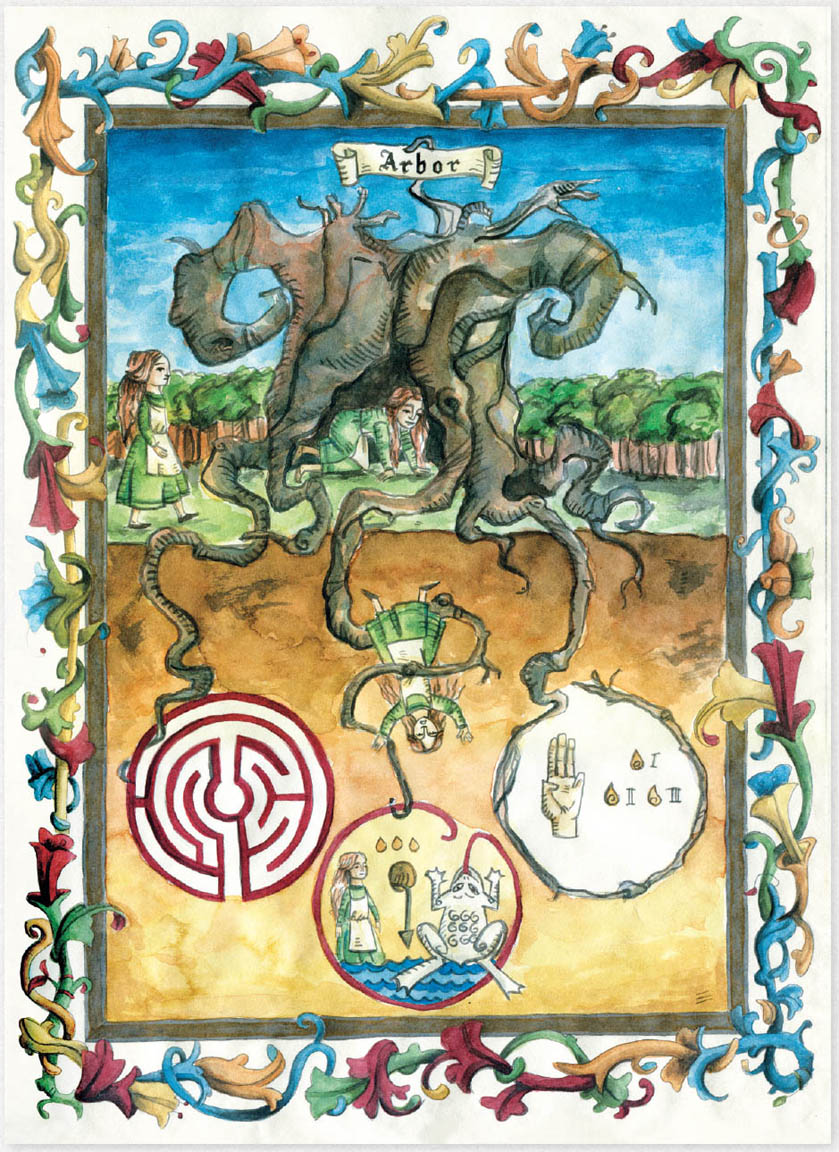

WHEN THE FAUN GIVES Ofelia the Book of Crossroads she officially begins the three tests required to regain her fairy-tale throne. It is a magical book—when she first opens it in the labyrinth, there are only blank pages; but when she is ready to embark on her quest and opens the book at the mill, the first task magically appears on a blank page. In fairy-tale language and imagery, a story is recounted of a time when the local woods were young and home to magical creatures that protected one another and slept in the shadows of the gigantic fig tree that grew on a hill near the mill. But now the branches are dried and the trunk is old and withered, because a monstrous toad has settled within the tree and won’t let it thrive. To complete her task and allow the tree to live again, Ofelia must put three magic stones into the toad’s mouth and retrieve a key from inside its belly.

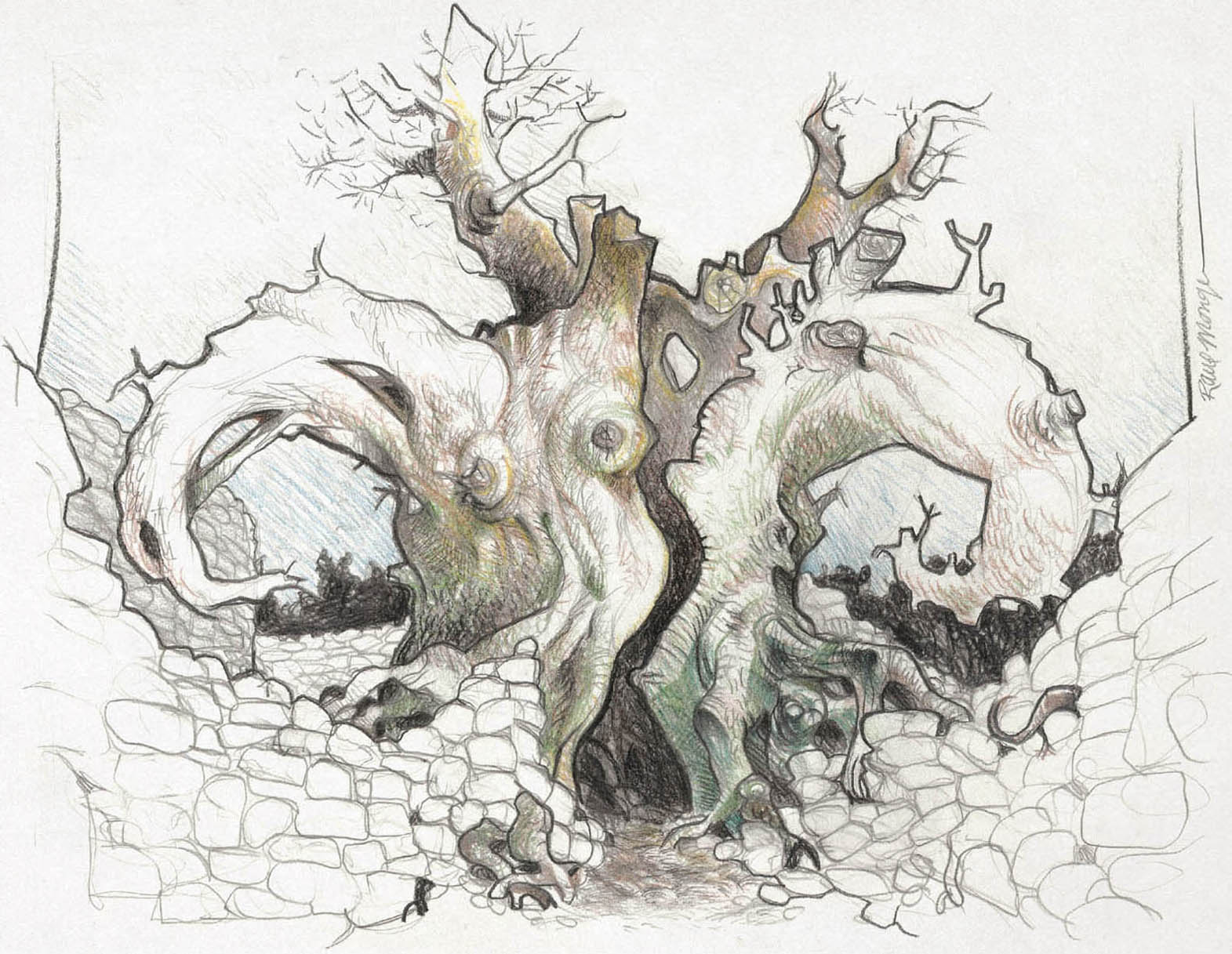

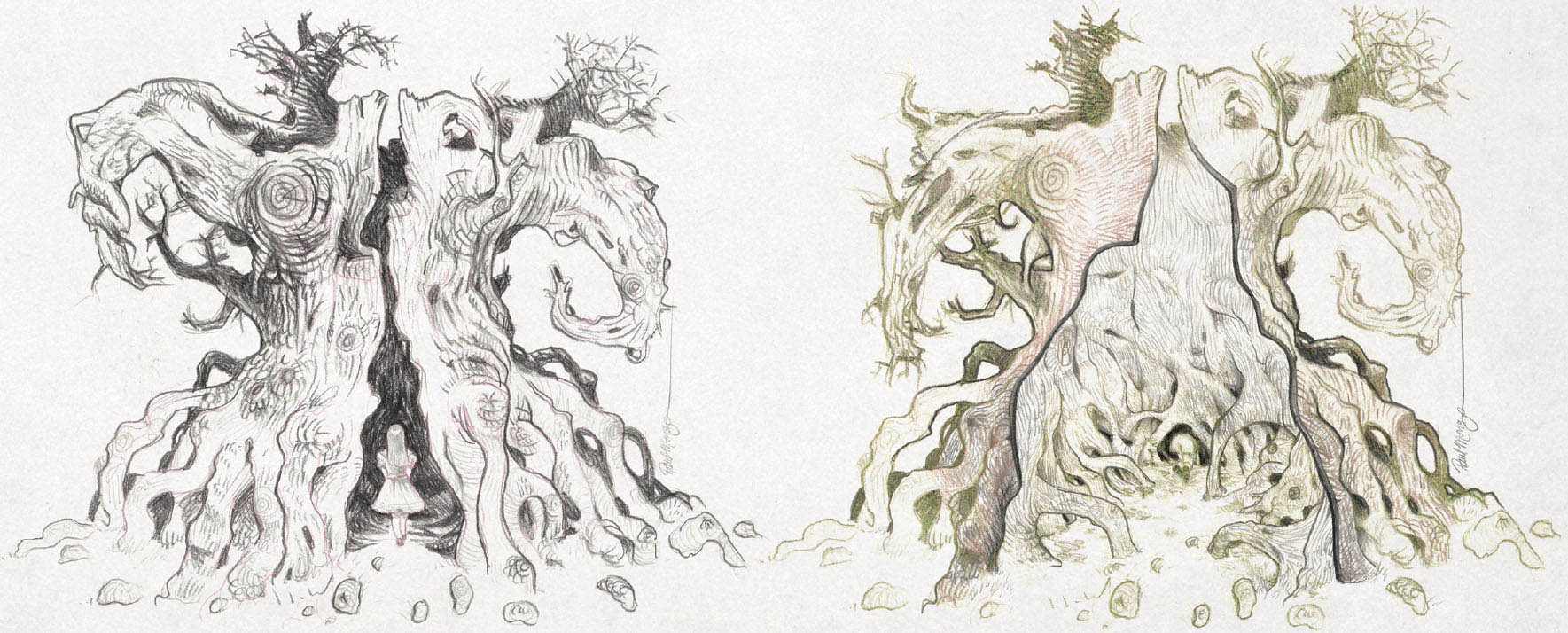

The tree on the hill is one of the film’s iconic images, its shape echoing the Faun’s horns and even the curvature of Fallopian tubes. As del Toro once scribbled in his notebook: “The fantasy world should feel UTERINE, INTERIOR, like the subconscious of the girl . . .”2 Arriving to her first test, Ofelia wears the dress her mother has made for her that purposefully recalls the one worn by Alice when she tumbled down the rabbit hole into Wonderland.

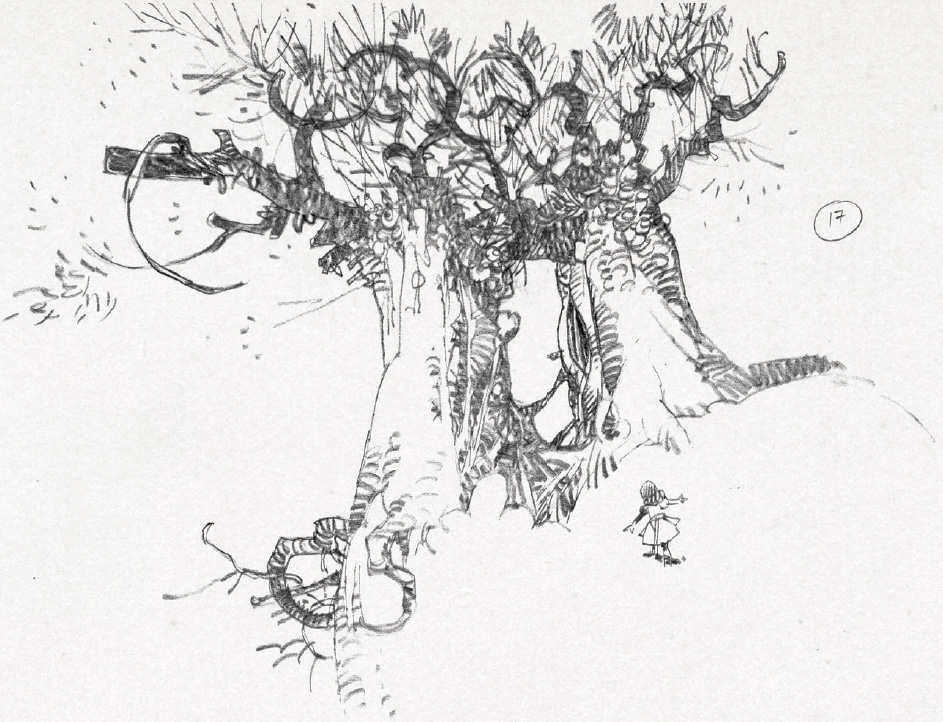

The art department’s design of the tree began with a del Toro notebook drawing and took form as a physical set of plaster and molds, dressed with real branches and CG touches by CafeFX. “What I really liked about Pan’s Labyrinth is we built it in a very beautiful way, using the mix of traditional ways of construction with top-of-the-line visual effects to complete the whole puzzle,” Caballero explains.

Maquette of the withered fig tree that is dying because of the life-sapping toad that now dwells within.

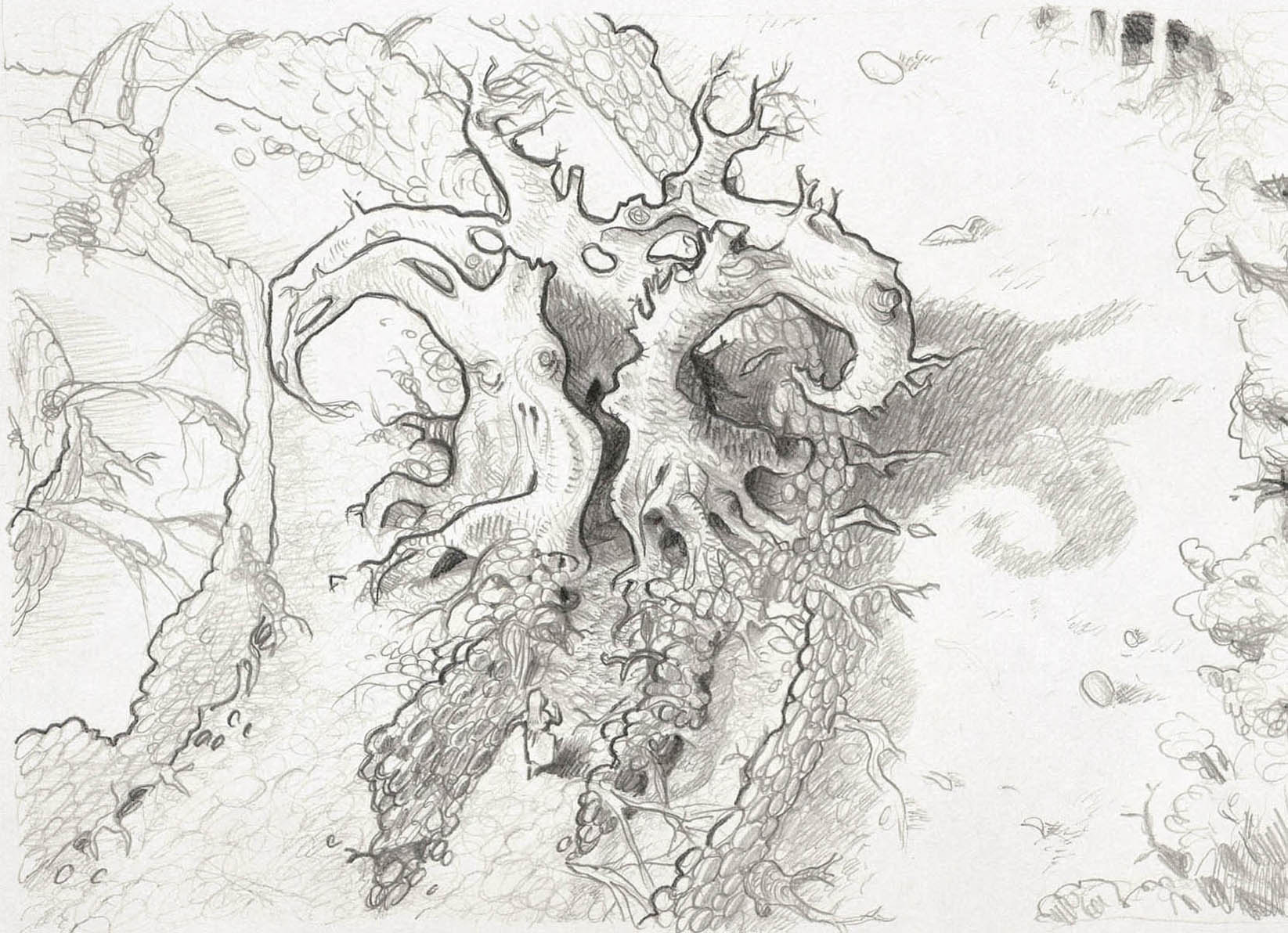

Conceptual art by Raúl Monge expands upon del Toro’s vision of the tree as an Alice in Wonderland–like passageway. The tree’s design mimics both the Faun’s horns and Fallopian tubes, the latter del Toro’s idea of a “uterine, interior” visual metaphor of the heroine’s subconscious.

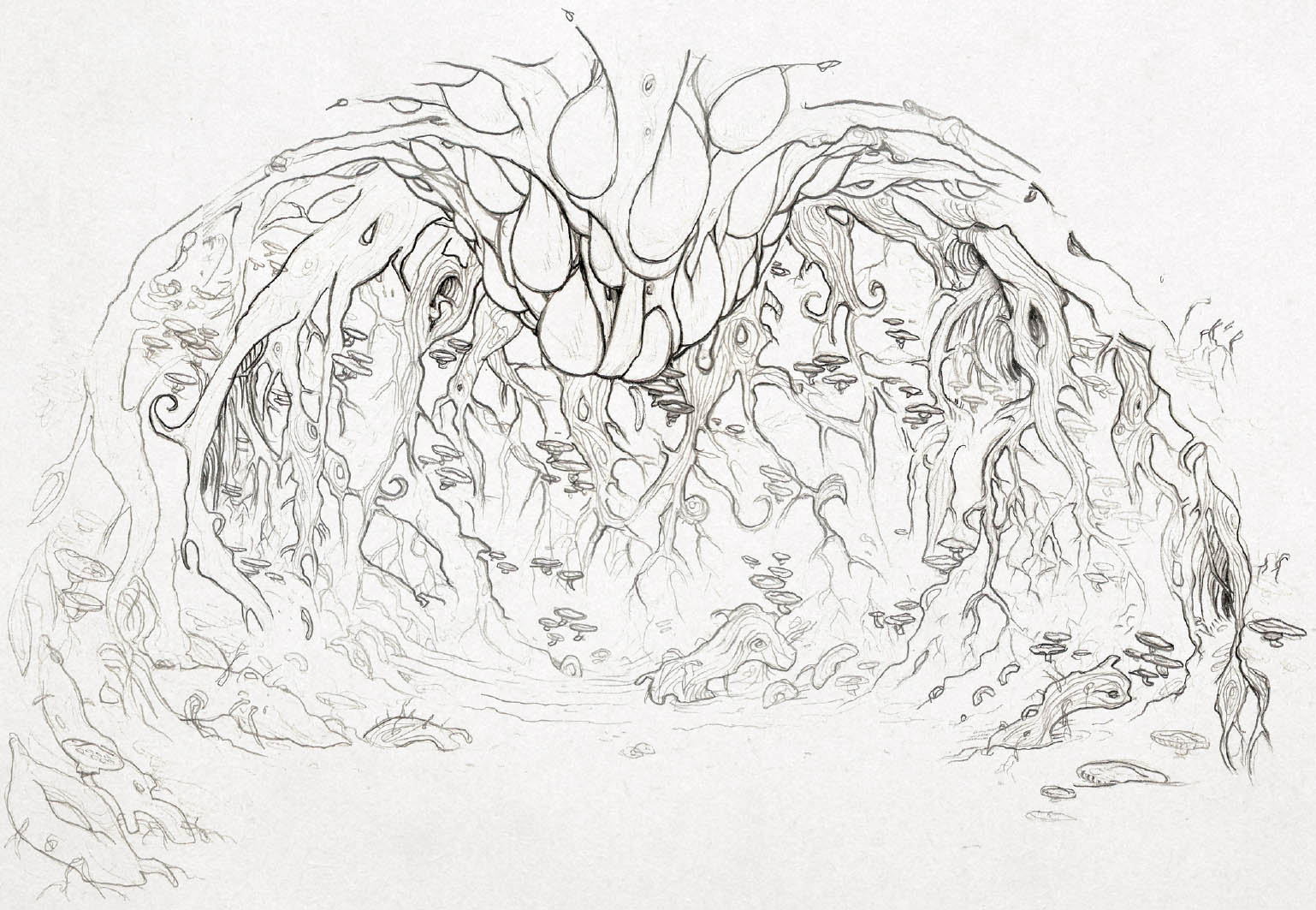

A detailed view of the “uterine” tunnel by Raúl Monge.

Ofelia in the tunnel sketch by Gabriel Liste.

A detailed view of the “uterine” tunnel by Raúl Monge.

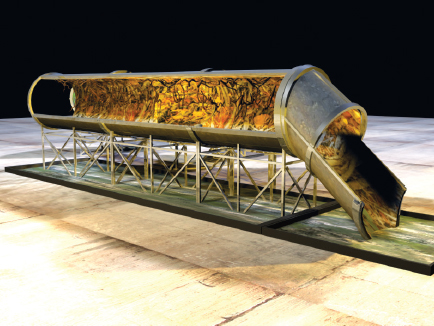

Digital concepts for the construction of the tunnel set.

“I think there’s a lot of warmness to that combination. It’s like a huge sculpture. The animation of the branches, and when the tree blossoms [at the end of the film], it is CGI. Pan’s Labyrinth was where my use of visual effects techniques began.”

Ofelia enters an opening in the tree trunk and finds herself in a different world—one that also differs in the final film from del Toro’s initial concept. The story of the toad in the tree is an example of how the limits of a tight budget, and the chaos that often and unexpectedly intrudes on a production, can derail a major sequence. Ultimately, it became an example of del Toro’s resourcefulness under pressure.

Originally, Ofelia was to crawl through a tunnel into an open cavernous space where she encounters the gigantic toad and subdues it. The tunnel set was ready, and the interior domed set was half built. Del Toro recalls the interior set as both the “most difficult” to construct but also one of the most magical in its conception, highlighted by a chandelier of roots and frozen tree resin that receives the light from the sun and illuminates the interior space. Under that magical dome, del Toro imagined Ofelia jumping on the toad and forcing it to eat the stones, one by one.

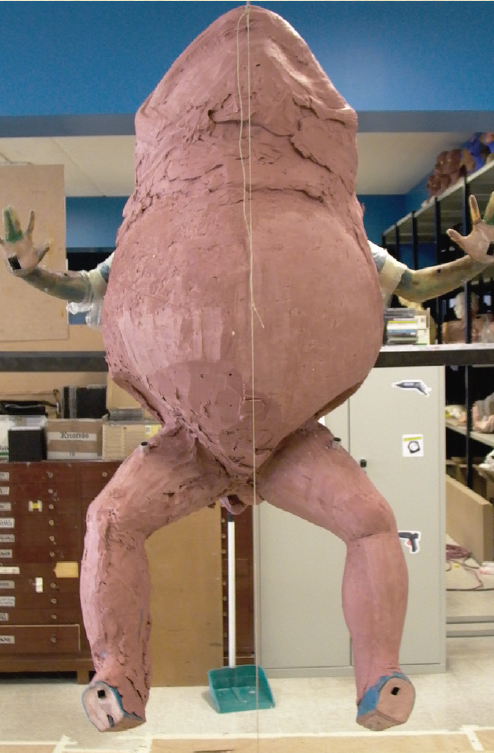

The toad was initially conceived as the size of a large dog that would be realized as a rod puppet. But when the ambitions for the sequence grew to having Ofelia climb atop the creature, the toad’s dimensions also grew, as Cinefex magazine reported, “to the size of a baby hippo . . . putting great demands on DDT co-owner Montse Ribé . . . who planned to puppeteer the five-foot-long foam latex puppet from inside.”3

Toad concepts by Sergio Sandoval. Del Toro wanted the “tests” for Ofelia to be based around stone, wood, and metal, like the three doors in the Pale Man’s lair. At this point in the toad design, the stone element is still present.

Ofelia crawls into the tree, film still.

The plan was for DDT to build a giant toad that could make the initial movement that precedes jumping, with CafeFX taking over from there. “The jumping was going to be digital,” says del Toro. The director wanted the giant toad to be made out of lightweight foam, with a thin silicone skin covering certain areas, but it would soon become apparent that the creature would still be too heavy.

DDT’s mixing machine and oven were too small at the time to handle the large creature, so they outsourced the mold to be filled with foam. “The only pieces made of silicone were the eyelids,” says Martí. “If we had made it entirely out of silicone it would be twenty times more heavy, and our frog was heavy enough.”

“We had many meetings about that frog and I kept saying to David, ‘It’s going to be too heavy, it’s going to be impossible to sustain,’” del Toro recalls. “I was never as good a sculptor and makeup effects guy as David and Montse are, but I knew the logistics because I ran a shop for a decade. The warning was ‘too heavy’ and it turned out to be as difficult as predicted.

Conceptual art by Raúl Monge of the dome-like space cut from the final film, complete with roots and frozen tree resin that reflected surface light to form an organic chandelier.

Conceptual art by Raúl Monge of the dome-like space cut from the final film, complete with roots and frozen tree resin that reflected surface light to form an organic chandelier.

On-set, Ivana Baquero begins the arduous tunnel crawl.

DDT artists at work on the slimy tunnel beetles.

“The first day we tested, after the first or second shot, Montse came out from underneath the frog trembling and covered in sweat,” del Toro continues. “Montse needed to make one big move, and she was doing her best, but she could not even move the frog slightly.”

“We’d need a cable to make it run or jump,” David Martí recalls. “The frog was one of the last things we shot and we were all tired and super stressed. Guillermo wasn’t happy with the frog; he was not happy with the whole thing.”

With a creature that was too heavy to animate by a person, and too cumbersome to rig on the half-built set, del Toro decided to rework the entire sequence. “In horribly rapid decision making, I decided to put Ofelia and the frog in the root tunnel and I rewrote the script so that Ofelia would tempt the frog to eat all three stones at once, pretending they were bugs, as opposed to one by one,” del Toro says.

The decision was made that the domed set would be scrapped and CafeFX would do most of the toad as a CG creation. When the toad’s tongue lashes out it’s another CG effect, with a practical silicon tongue used only when it makes contact with Ofelia. When the tongue laps up the bug offered in Ofelia’s outstretched hand—and, unknowingly, the stones—the toad vomits up its insides. The resultant goo was a physical gelatin mold that accompanied CafeFX’s creation of what Burrell calls “a big CG sack” for the outer skin that withers and melts, leaving both the puddle of vomit and the key Ofelia seeks.

Burrell recalls the synergy between CafeFX and DDT as positive, “one of the best ever” examples of teamwork between the effects disciplines in his experience: “Guillermo used us both, practical and CG, and used us to his advantage.”

“I always believe things happen for the best,” del Toro concludes. “Everyone thinks of the director as a dictator, but it’s not that. You know when you have to do it the way you want it. But I think the big difference in being a first-time director, and one who has directed six or ten movies, is that with experience you learn to identify adversity not as adversity, but as opportunity. That distinction makes you much more flexible.”

The final toad proved too heavy to physically animate and would largely be visualized on screen as a CG creature created by CafeFX.

Dirty and dazed, Ofelia emerges with her prize—a key vital to completing her second task.

The toad taking form at DDT, from miniature mock-up to full-scale creature. The original plan was for Montse Ribé (seen here at work), to be inside the creature and physically animate it.

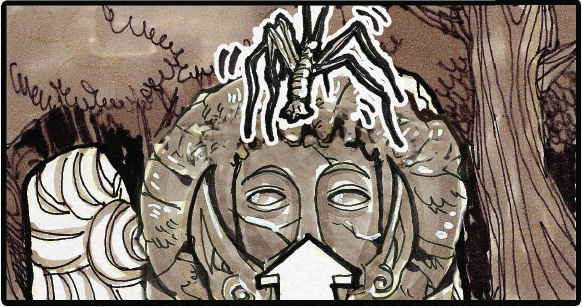

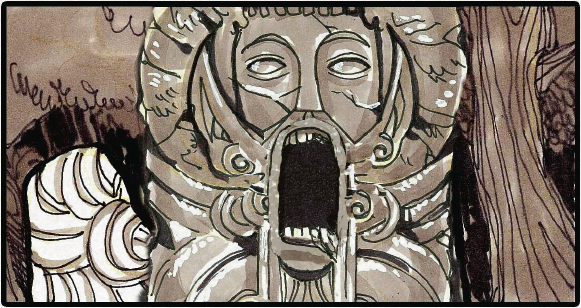

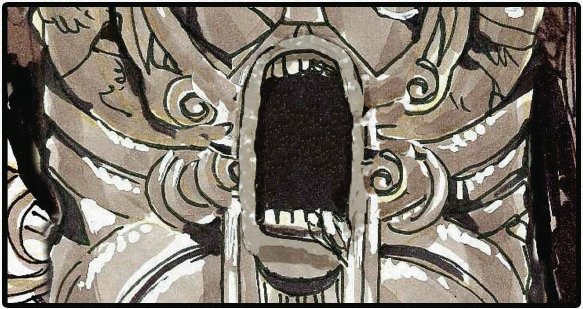

BELOW: A storyboard sequence by Raúl Monge showing the winged stick bug crawling out of the mouth of the ancient monument. The stick bug later transforms into a winged fairy and leads Ofelia into the labyrinth.

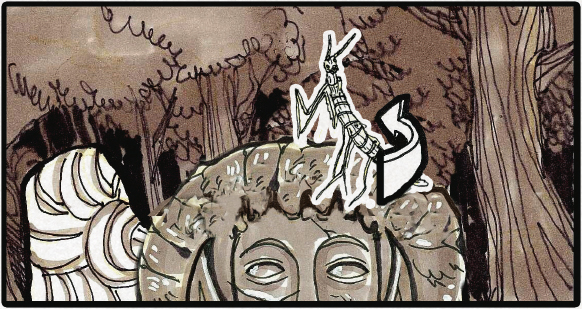

BELOW: Storyboard sequence by Raúl Monge showing the stick bug turning into the classic winged fairy pictured in Ofelia’s storybook.

BELOW: A storyboard sequence by Raúl Monge plots, in excruciating detail, Vidal’s brutal bludgeoning and execution of a young man, along with the shooting of his father.

BELOW: A storyboard sequence by Raúl Monge follows Ofelia’s first encounter with the Faun and his fairy emissaries and her first experiences with the Book of Crossroads. When she opens the magic book, its blank pages fill with imagery pertinent to each stage of her quest.