How Singapore Became Smart

No army, however brave, can win when its generals are weak.

Singapore’s geography and lack of resources, as suggested in chapter 1, are innately challenging. And its national history has been likewise difficult, from the very inception in the mid-20th century. The saga of Singapore’s first two decades, in particular, illustrates clearly why Singapore needed to be smart, in the sense of being strategically yet pragmatically responsive, long before the opportunities to become smart in a narrower cybernetic sense began to arise. Singapore’s early history also shows how proactive leadership was crucial to creation of the city-state’s distinctively open and holistic institutional architecture, collaborative policy style, and willingness to learn from abroad. All those qualities, embedded long before the Digital Revolution, later made embracing smart ICT possible. The difficult history of those founding years also shows why crisis consciousness remains so deeply ingrained in both Singaporean political leaders and in their bureaucractic counterparts even today, driving them continually toward far-sighted policy innovation.

More recent developments—the Gulf War, the Asian financial crisis, 9/11, and the Lehman shock in particular—reaffirm that perils persist for a small city-state exposed to a turbulent world. Like earlier crises, these have profoundly shaped local institutions, configuring them to be flexible, adaptive, market-conforming, and responsive to new technological options. History and a perpetually strong consciousness of its varied political-economic perils thus continue to exert a powerful impact on the evolution of Singapore public policy, even in the IoT era. Perpetual crisis consciousness and flexible institutional structure render Singapore’s institutions resilient, and its leaders resourceful, in the face of strong, volatile outside forces.

Singapore has been blessed with visionary leaders across its short but turbulent history. Yet a tiny band of individuals, no matter how capable, cannot singlehandedly manage even a small nation-state in the modern world with precision. In the long run, it is well-configured institutions, rather than philosopher kings, that enable nations to meet challenges with enduring strategic responses. As this chapter makes clear, a full understanding of Singapore’s smart state must take note of how those key institutions emerged and flourished.

This chapter recounts chronologically the emergence and evolution of Singapore’s smart institutions and smart group dynamics. That is best done by observing how its ministries, statutory boards, and para-public firms—in a word, its leadership—have grown increasingly skilled over the past half century in perceiving and responding to their political-economic environments, first by applying pragmatic common sense, and later by employing technology. It is thus essential to examine the impact of people, organization, the rule of law, and finally technology in making Singapore responsive to its pressing domestic and international challenges.

This chapter chooses the lens of crisis and response as an organizing concept for understanding how smart-state capabilities historically evolve. It focuses especially on how particular crises led to innovative responses that in turn enhanced Singapore’s ability to be smart in a pragmatic yet strategic sense. It explores further whether states have grown smarter in iterative fashion, due to the enormous magnitude of the challenges that they faced at critical junctures; the quality of their leadership at such junctures; and the capacity of institutions and technology to assist in perceiving and responding to subsequent challenge. To understand creative responses to crisis that result in institution building, it focuses on the interaction among leadership, institutions, and policymaking processes.

This analysis further argues that positive leadership practices serve as a key catalyst for inclusive organization. They create a sense of community that makes teamwork—and ultimately innovation—much easier. The framework and operating procedures established by insightful leaders continue to benefit a nation, however, only as long as the parameters they create persist in adjusting to their evolving outside context, and continuing to align with new group dynamics brought about by succeeding generations of leadership.

In each leadership era of its short history, ever since attaining self-government in 1959, Singapore has faced distinctive challenges. Each leadership tenure roughly symbolizes an era in the evolution of the smart state:

—Under Lee Kuan Yew, it was the age of independence and state formation (1959–90).

—Goh Chok Tong oversaw an era of greater relaxation and experimentation, as the information revolution proceeded, with transnational interdependence deepening (1990–2004).

—Lee Hsien Loong faced an age of full-scale globalization, digitalization, and presentation of the Singapore model to the broader world (2004–present).

Singapore’s political history can thus be divided along the lines of national leadership, with the latter two linked through a common challenge of global interdependence, although the shadow of Lee Kuan Yew casts itself across all three eras.

Throughout the three formal leadership tenures, Singapore public policy has remained flexible and creative, thanks to consistently smart institutions, updated with the latest technology and responding effectively to changes in domestic, regional, and global environments. A unicameral legislature, for example, in contrast to the more complex American, European, and Japanese systems, has no doubt made effective leadership easier, and probably smarter in the sense of being more perceptive of and more responsive to outside social forces. So have Singapore’s major specialized statutory boards, especially the Housing and Development Board (HDB), Central Provident Fund (CPF), and Economic Development Board (EDB), which focus on housing, finance, and foreign investment challenges, respectively. This chapter will explore the role of leadership in configuring these distinctive outcomes, and how it critically aided in creating the smart Singaporean state, in both its pragmatic and its technologically sophisticated dimensions.

An empirically based analysis of the subject cannot proceed, however, without first examining the conceptual meaning of smart institutions and the varied ways that they can help to remedy common organizational pathologies. With that foundation, it becomes clear that Singapore’s government became smart in two distinct phases, largely in response to dual stimuli: political-economic crisis and technological change. The concept of critical juncture is used here to delineate periods of particular fluidity and decisive institutional transformation.1

For theorists such as Max Weber, bureaucracy is the apotheosis of organizational forms and the bureaucratic state is intrinsically “smart”—so there is little need to evolve in that direction.2 Revisionist literature, however, has pointed out at least four pathologies that can affect the performance of bureaucratic states in the real world:

—Clientelism: George Stigler finds that the regulated have strong incentives to coopt their regulator.3

—Routinization: Anthony Downs notes that as bureaucracies expand, they become preoccupied with internal coordination rather than external response.4

—Vertical communication: In Michel Crozier’s view, bureaucracies often grow stalemated owing to pathologies in top-down information flow and incentives.5

—Inadequate Institutionalization: Samuel Huntington adds that state structures may be inadequately configured to accommodate rising popular desires for political participation.6

All of the foregoing analysts seriously question the actual performance of actual nation-states in some parts of the world, in the course of their theoretically guided investigations. Yet the ills of governance they describe have been effectively avoided or largely countervailed in Singapore, demonstrating its unusual capacity to operate as a smart state in the pragmatic/strategic sense and creating the analytical puzzle that inspires this research.

In neutralizing the classical pathologies of governance outlined above, smart institutions in Singapore exhibit three notable operational traits that enhance their effectiveness.

First, Singapore’s smart institutions pursue an integrated approach to challenges. They think and act holistically, not only over time (integrating the short and long term) but also across interorganizational boundaries. They tackle multiple problems, in short, with a unified approach, or through collaborative effort.

Second, they recognize the importance of the group dynamic within their smaller subunits. They invigorate individual ministries, statutory boards, and other public organizations by recruiting high-quality young participants. And they enhance the communications potential of those bodies by nurturing strong vertical, cross-generational networks. The incentive structures that smart institutions in Singapore create thus help to motivate efficient and ambitious individuals to join the government institutions being reconfigured. Smart states and cities also confer responsibility on younger, able individuals, rather than allocating posts solely on the basis of seniority. Singapore seems willing to risk bringing fresh people with new perspectives into high-profile meetings and training them for greater responsibility.

Third, smart institutions are also less prone to clientelism, because transparency and distance from political bodies are embedded in their architecture, as well as in their environment. Singapore’s powerful statutory boards, which report to ministries rather than to politicians, are a clear case in point. In keeping with the leadership’s strong insistence on continuous innovation to keep abreast competitively with developments elsewhere in a changing world, the structure of such technocratic bodies comes under continuous, systematic review by knowledgeable arbiters, subject to sunset provisions that weed out seemingly ineffective approaches.

In short, Singapore smart institutions avoid pathologies classically ascribed to the bureaucratic state, while retaining positive aspects of “embedded autonomy.” From a historical perspective, their evolution in this regard can be divided into two distinct eras: an early phase and a later phase, differentiated by the salience of globalization. The following analysis considers how smart institutions have evolved in Singapore itself, noting where relevant any notable contrasts to evolutionary patterns elsewhere. Historical comparison provides a more refined understanding of just what makes the Singaporean smart state and smart city distinctive, and worthy of consideration elsewhere as policy paradigms, which future chapters propose to do.

Early Phase: Challenges during the 1960s

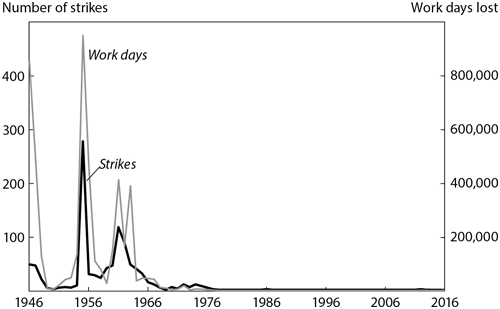

During the early postwar years (1945–55), before self-government, Singapore was rocked by multiple sociopolitical challenges, as were other transitioning states in Asia, including India, China, Burma, Malaysia, and Indonesia. This turbulence reached a particular pitch in the mid-1950s (figure 3-1), against a backdrop of painfully high unemployment—it was nearly 14 percent when Singapore attained self-government in 1959. The fledgling polity also faced complex ethnic tensions, such as the Hock Lee bus riots (April 1955) and the Chinese Middle School riots (1956), as well as pervasive labor unrest. Neither the high unemployment nor the endemic social tensions were to fully subside for nearly a decade.7

Amid this unrest and unease, consolidating regime stability and neutralizing ethnic unrest were political challenges that helped catapult the People’s Action Party (PAP) to power, less than five years after its founding in November 1954. With the PAP winning 43 of the 51 seats at stake in the 1959 general election, victory made Lee Kuan Yew chief minister at the tender age of 35.8 The PAP victory was met, however, with broad dismay among multinational firms, which saw the party as radical and dominated by communists. In protest, several of these firms moved their headquarters from Singapore to a more congenial and conservative Kuala Lumpur.

Figure 3-1. Number of Strikes and Work Days Lost, 1946–2016a

Source: Chong Yah Lim, Singapore’s National Wages Council: An Insider’s View (Singapore: World Scientific Publishing, 2014), pp. 151–52. Number of strikers in 2012 SMRT strike from Cheryl Sim “SMRT Bus Drivers’ Strike,” 2015 (http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/infopedia/articles/SIP_2015-03-11_162308.html).

a. Over the past four decades (1976–2016), Singapore has experienced only two strikes: the 1986 Hydril strike (122 work days lost) and the 2012 SMRT bus drivers’ strike (518 work days lost).

As it struggled to consolidate power, the PAP too faced multiple, interrelated domestic challenges—from the unions, the left, and the forces of Chinese nationalism. A major concern was the rising strength of communists within both the party and broader Singapore society, especially in the unions. In August 1961 the PAP split, with 13 pro-communist PAP assemblymen breaking off to form the Barisan Sosialis.9 As many as 30 percent of the Singapore electorate in the early 1960s were estimated to be communist sympathizers, with a special concentration at Chinese schools such as Nanyang University.10

Emotional identification with the Chinese revolution, coupled with frustration at the lack of job opportunities for non-English speakers amid high general unemployment in Singapore, made local Chinese particularly susceptible to leftist appeals. More conservative Chinese nationalist groups, such as the Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce (SCCC), also opposed the PAP’s efforts to dominate Singapore politics by propounding a broad, ethnically inclusive, and cosmopolitan concept of national identity. The ethnics in particular resented being charged with “Chinese chauvinism” by the PAP’s solidly ethnic-Chinese leadership, viewing this as political opportunism and a betrayal of Sinic solidarity.

To address these issues, the PAP initially opted for force but eventually found merger with Malaysia to be more practical, until the federation’s eventual collapse in 1965 triggered another social challenge and political crisis. While stressing its own socialist character, the PAP-led government moved first against the radical unions with the passage of the 1960 Trade Union Act, which allowed it to deregister many of these unions. Then it played the racial card, criticizing groups educated in ethnic schools such as Nanyang for championing the cause of exclusivist education and for advocating special standing for the Chinese language in Singapore. Similarly, in February 1963 the government’s security forces launched Operation Cold Store. In one night, nearly 150 journalists, student leaders, labor activists, and opposition politicians were detained without trial or charges under the Internal Security Act. In many instances, the detentions were not even acknowledged by the government.11

The government then sought to consolidate all legitimate union activities in corporatist fashion under its own state-led National Trades Union Congress (NTUC). Eventually, the PAP sought stability in federation with Malaya, rather than through further local institution building, in order to dilute its pronounced domestic difficulties and external challenges. In July 1963 Singapore, Malay-dominated Sarawak, and peninsular Malaya formally merged, creating a new, ethnically hybrid state that was 53 percent Malay, 37 percent Chinese, and 10 percent Indian.

Confederation with Malaya and Sarawak did not solve Singapore’s internal political problems, however. Nor did it provide broader opportunities for Singaporean influence within a larger, multiethnic state, as Lee Kuan Yew and others had initially hoped. Lee’s PAP did not do well in either the late 1963 “Malaysian Malaysia” campaign or the ensuing 1964 Malaysian general elections, only winning one out of nine contested seats.12 Lee also refused to grant ethnic Malays, who were politically dominant in peninsular Malaya, the same preferential treatment in Singapore, to which Malays felt they were entitled, as the largest ethnic group in the Malaysian federation as a whole.13

Ethnic tensions thus began building in both Singapore and Malaysia, despite their nominal unity within the Malaysian state of the day. Singapore experienced two more serious race riots in 1964—one in July that resulted in 23 deaths, 454 injuries, and 3,568 arrests; and a second in September that led to another 13 deaths, 106 injuries, and 1,439 arrests for rioting and curfew breaking.14 The first was provoked by Muslim radicals following a mass rally on Singapore’s Padang to commemorate the prophet Muhammad’s birthday, while the second was triggered by the murder of a Malay trishaw driver, ostensibly at the hands of local Chinese.

Along with domestic ethnic tensions, an international factor called into question the viability of the nascent Singapore-Malaya union: undeclared war (Konfrontasi) from Indonesian president Sukarno. Just across the Strait of Malacca, Bung Karno (Comrade Karno) fiercely opposed and vowed to destroy the fledgling union as a “neo-imperialist tool” of the British and other allegedly nefarious powers. This Konfrontasi consisted of not just pitched jungle battles in Sarawak and Kalimantan, but also sabotage, including 29 bombings within Singapore itself. In the most egregious incident, perpetrated in March 1965, Indonesian commandos bombed MacDonald House in Singapore (home of Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank), the local Australian High Commission, and the Japanese Consulate. These assaults resulted in three deaths, including that of the assistant to the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank branch manager.

Singapore’s leaders, including possibly Lee Kuan Yew himself, realized well before its actual breakup that the Malaysian federation might not endure.15 Eventually, on August 9, 1965, the Malaysian parliament voted to formally expel Singapore from the Malaysian union. And also on August 9, Singapore declared its own independence. With its PAP government confronting high unemployment, a housing crisis, Indonesia’s Konfrontasi, and a deepening challenge from communist unions, not to mention the rapidly expanding Vietnam conflict steadily deepening less than 700 miles (1,100 kilometers) to the northeast, prospects for the fledgling city-state did not look bright, to put it mildly.

Increasingly on its own in facing domestic and international troubles, Singapore sought innovative responses, which in turn fostered the creation of smart institutions. On the domestic front, this approach was applied to high unemployment, a lack of infrastructure, and a housing crisis, as well as tensions between ethnic and ideological groups. On the international front, security became a deepening challenge with the escalation of the Vietnam War following full-scale U.S. intervention (February 1965) and the gradual outbreak and intensification of the Chinese Cultural Revolution between late 1965 and May 1966.16 Also fatefully important was Harold Wilson’s January 1968 decision to withdraw British forces from east of Suez. By October 31, 1971, all of Britain’s forces had left Singapore, after more than 150 years of sustained presence, apart from World War II. The Lion City-State faced a deepening security challenge, with the Vietnam War raging nearby and the Chinese Cultural Revolution in full bloom.

Response to Early Challenges: A Cohesive, “Smart-State” Leadership Team Emerges

These domestic and international challenges placed Singapore at a critical juncture in its early days—it was a period of fateful indeterminacy, lasting more than a decade (1959–71), in which leadership decisions had the scope to exert a profound and creative impact on the city-state’s still-malleable future.17 Those decisions owed much to the key leaders and the decisionmaking structure in place at the time. The leaders were few in number and diverse in background. Yet their early actions played a central role in establishing internationally distinctive institutions that configured Singapore public policy along lines that persist to this day and that continue to enhance its smart-state capacities. The broad network of associations and information exchange spawned by their informal ties gave rise, in turn, to a holistic policy approach that has augmented the quality of governance in Singapore. In later years this holistic approach also facilitated Singapore’s rapid response to the Digital Revolution and the Internet of Things, further amplifying Singapore’s ability to cope with rapid socioeconomic changes, both at home and abroad.

Despite diversity of background, Singapore’s early leaders, who worked closely together through important formative experiences, shared important common personal characteristics and approaches to problem solving. This commonality was a key prerequisite for the collegiality and lack of sectionalism that were to become a hallmark of Singapore policymaking in future years. All were risk-takers who also took an integrated, holistic approach to the issues they confronted. All had served in a broad variety of policy roles and refused to let bureaucratic rivalries stand in the way of a pragmatic, common approach to Singapore’s substantial domestic and foreign challenges. Known commonly as the Old Guard, this tightly knit group displayed a strong mutual commitment to collective welfare, synergistic with their diversity of backgrounds and personalities, that inspired both the development of smart, flexible institutions and a common cosmopolitan pragmatism that has greatly aided Singapore’s globalization.

The central player on this team was of course Lee Kuan Yew, the young, formidable, and pragmatic new chief minister. Of Hakka and Hokkien ancestry, Lee was a labor lawyer with a Cambridge education who had cofounded the ruling People’s Action Party in 1954, in an expedient alliance with pro-communist trade unionists. Influenced profoundly in his early days by both Fabian socialism and Arnold Toynbee’s notion of “challenge and response,” Lee believed that change was constant in world affairs, and that existentially exposed Singapore needed to continually innovate in order to survive.18 Moreover, its innovations had to combine broad and eclectic concern for social welfare with a hardheaded appreciation of the virtues of self-help. From the very beginning, Lee’s strong belief in a holistic approach and specialized, case-specific expertise—the “helicopter quality,” as he put it—left a lasting imprint on Singapore’s pragmatic policies and dynamic decisionmaking processes.19

Among the Old Guard were Goh Keng Swee, Lim Kim San, Toh Chin Chye, and Sinnathamby Rajaratnam—each playing distinct, versatile roles in creating an economically vibrant, socially stable, politically consolidated, and internationally savvy—as well as smart—Singapore. Goh spearheaded the Economic Development Board, and Lim the Housing and Development Board—two cornerstones of the Singaporean smart state, which variously addressed emerging economic and social challenges in highly concrete and pragmatic fashion. Toh played a similar role at the People’s Action Party, which mediated political pressures to ensure stability for half a century, through an eclectic blend of low-cost government and broad social coverage that cuts across left-right divisions in Europe and the United States. Rajaratnam drafted an oath of allegiance that served as a pillar of support for multiethnic solidarity and political stability. Several of these individuals, especially Rajaratnam, helped to build the smart state in the international arena as well.

Deeply trusted by Lee, Goh Keng Swee was the mediator and innovator of Lee’s early leadership team, often acting as his intermediary on delicate controversial missions. Born in Malacca to a Peranakan family, Goh was a man of unusual decisiveness and creativity.20 After serving as Singapore’s first minister of finance—initiating the smart EDB, as well as the Jurong Industrial Estates during his term at this post—Goh became first minister for the interior and defense (1965–67) following independence, tasked with building a local defense force, and at this time introduced the concept of compulsory national service. He again held the position of minister of defense in 1970–79, following Britain’s fateful decision to withdraw from east of Suez, and later also served twice as minister of education (1979–80 and 1981–84). Ultimately Goh was deputy prime minister to Lee from 1973 to 1980, before retiring in the latter year.

Lim Kim San, first chair of the Housing and Development Board (1960–63), was the Old Guard’s organizer and planner. He brought the dreams of others down to earth and realized them in brick and mortar. A businessman who commercialized a unique machine to produce sago pearls cheaply, he grew wealthy by his mid-30s and went on to become the director of several banks. Like Goh, Lim was trusted implicitly by Lee Kuan Yew.

After decisively addressing the chronic housing shortage, which had left 400,000 people in squatter conditions during the early 1960s, Lim was assigned to various ministerial posts: national development (1963–65), finance (1965–67), defense (1967–70), education (1970–72), national development once again (1975–79), and environment (1979–81). He also served as chair of the Public Utilities Board (1971–78), in which capacity he oversaw the development of new water reservoirs; and as chair of the Port of Singapore Authority (PSA, 1979–94), during which time Singapore became the world’s number one container port.21 Its successor, PSA International, has grown to become arguably the world’s smartest global port operator, with business at 29 ports in 17 countries.22

Toh Chin Chye, noted for his persuasive skills, was the political operative on Lee Kuan Yew’s early team. The two met in London when Toh was chair of the Malayan Forum, an anticolonial Southeast Asian student group. Toh collaborated with Lee for nearly 30 years (1954–81) as chair of the People’s Action Party, one of the most durable ruling parties in the world. In that capacity, Toh cast the deciding vote for Lee in the initial party election for prime minister in 1959 and led the fight thereafter against leftist elements in the PAP. Toh held several key government posts, including deputy prime minister (1959–68), minister for science and technology (1968–75), and minister of health (1975–81). He also chose “Majulah Singapura” as Singapore’s national anthem and headed the team that designed Singapore’s coat of arms and flag.

Sinnathamby Rajaratnam, Lee Kuan Yew’s early foreign-policy confidant, helped to build an ethnically integrated nation that reconciled the non-Chinese communities to Han dominance. Born to a Tamil family in Jaffna, Sri Lanka, the cosmopolitan Rajaratnam was raised in Malaya and educated at Singapore’s elite Raffles Institution, then at King’s College in London, returning to Singapore after World War II as a journalist. After a stint at The Straits Times, he cofounded the PAP together with Lee Kuan Yew and others, becoming minister of culture in Lee’s first cabinet (1959). Following independence from Malaysia, Rajaratnam served as Singapore’s first foreign minister (1965–80), then as minister of labor (1968–71), and deputy prime minister (1980–85). Rajaratnam negotiated Singapore’s entry into the United Nations (1965) and the Non-Aligned Movement (1970), while also serving as one of the founding fathers of ASEAN, when it was established in 1967. A strong believer in multiracialism for Singapore, he drafted the Singapore National Pledge in 1966 stressing the nation’s multiethnic character and solidarity, only two years after the serious 1964 race riots and in the immediate aftermath of independence itself.23

Clearly, Lee Kuan Yew had assembled an extraordinary group of advisers—with an unusual degree of camaraderie, owing not just to the fact that they had all studied overseas in London but also to their common commitment to the subsequent independence struggle. Ezra Vogel has labeled this clique a “macho meritocracy”—a group so able and incorruptible as to generate a special aura of speculative awe providing “a basis for discrediting less meritocratic opposition almost regardless of its arguments.”24 This elite group possessed exceptional esprit de corps and highly complementary personal traits that enhanced the efficiency of their leadership as a whole.25 They also had an uncanny sense of the importance of institution building, as well as a striking understanding of global best practice and of effective policy implementation.26 The Old Guard and their well-coordinated policymaking practices were, in a word, ideally suited to their historic role as the architects of new smart institutions.

Building the Smart State: Crafting Its Logic and Overall Design

These gifted members of the Old Guard laid the institutional cornerstones of Singapore’s smart state—the ministries, the PAP, and statutory boards such as EDB and HDB—during the long tenure of Lee Kuan Yew as their formal leader (1959–90). Many of these individuals, and most of their technical subordinates, were engineers—particularly systems engineers. As discussed earlier, smart states and cities typically have an integrated, engineering-style approach to challenges, approaching them holistically, to provide single solutions for multiple problems with both short- and long-term relevance. This penchant for holistic thinking has been pronounced in Singapore, as the cases of the EDB and HDB illustrate, in part because of this common engineering background. Smart institutions, including those embedded in ethnic communities, such as the People’s Association, recognize that positive internal group dynamics within subnational groups can give scope and incentives to able recruits from a diversity of age and ethnic backgrounds.27

To formulate, implement, and sustain policies capable of meeting the formidable challenges confronting their fledgling state, Lee Kuan Yew and his Old Guard colleagues recognized that they needed a policy apparatus sensitive to issues on the horizon, but sufficiently insulated from political pressures and cumbersome administrative procedures to respond intelligently and flexibly to them. Achieving that dual capability meant creating both a distinctively stable political environment for policymaking and also a set of governmental institutions capable of formulating intelligent responses. After outlining from a comparative standpoint the recipe for a smart state that Singapore devised in general terms, this chapter will proceed to show more concretely how the past architects of the smart state—both Lee Kuan Yew and his two able successors—went about building this edifice.

Overall Configurations. Operating within a formally democratic political context of one-party rule, Singapore has relied on the People’s Action Party to provide top leadership ever since independence. The National Assembly is unicameral, with the PAP continuously holding more than two-thirds of all seats. This arrangement, which allowed the PAP to unilaterally revise the constitution with its two-thirds majority, has provided stability to the policymaking process and predictability to policies themselves. It has, however, also intensified the dangers of clientelism, against which Singapore’s leadership has been forced consciously to fight.

The architecture of Singaporean government institutions is distinctive in comparative context: unique structural elements, together with a holistic orientation, enhance its ability to both perceive problems and respond rapidly to them. Apart from Singapore’s simple and distinctive political institutions, such as a unicameral legislature, the city-state also features narrowly focused ministries oriented to addressing perceived social needs. Under their general jurisdiction, it has distinctive statutory boards and para-public firms that implement policies in remarkably dynamic fashion, more insulated from political pressures than is typical of bureaucracies in most parts of the world. To prevent stovepiping, a cohesive elite administrative service without strong countervailing ministerial loyalties unifies the bureaucracy at the top.

As in most nations, Singapore has ministries to perform the classical functions of government—supervising finance, trade and industry, defense, transport, communications, and so on. Among its 16 ministries, however, Singapore also features some unusual configurations, rarely found in other parts of the world, which enhance the efficiency of policymaking. These include a Ministry of Environment and Water Resources, which directs Singapore’s unusual and strategically important approach to water issues; a Ministry of Manpower, which coordinates the city-state’s distinctive focus on human resource development; and a Ministry of Culture, Community, and Youth, which works to systematically weld the unusually diverse ethnic mixture within Singapore into a coherent nation.28

Among Singapore’s major ministries, two deserve special mention for the important role they play in supervising other highly dynamic semi-governmental bodies, while insulating them from political pressures that could distort their operation. One is the Ministry of National Development, which supervises the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) as well as the Housing and Development Board. These are the key bodies implementing Singapore’s highly distinctive and successful housing policies—a linchpin of socioeconomic progress and political stability. The second is the Ministry of Transport, which oversees the Land Transport Authority (LTA) and the Public Transportation Council (PTC). These organizations are responsible for highly successful mass-transit policies that have enabled Singapore to control air pollution and traffic congestion, even as it has worked to decentralize economic activity and to create a sense of spaciousness in its living environment.

The Key Role of Statutory Boards. While Singapore has a relatively conventional ministerial structure, it is distinctive in the powerful role that it accords to the subordinate implementation bodies, the statutory boards. These are autonomous agencies of government established by acts of parliament and overseen by government ministries. They are not staffed by civil servants, so have somewhat more operational flexibility and frequently broader technical expertise than the ministries. They also draw in many employees as well as some directors from the private sector, enhancing the sensitivity of the boards to broad market trends.

The boards thus give the working-level officials that lead them a clear, specific mandate for action, allowing those officials to sidestep the cross-ministerial bureaucratic politics that often complicate implementation elsewhere in the world. The boards also shield operating officials from the political accountability prevailing in ministries themselves, rendering bureaucratic action in Singapore unusually technocratic and impervious to politically inspired and budget-busting patronage politics. The statutory boards have the added final merit of devolving policy decisions to small organizations with clear oversight responsibilities, giving such bodies the ability to take quick and effective action when needed.

Under colonial rule, statutory boards were relatively inconspicuous, with static functions. Yet since 1959 they have proliferated and grown rapidly to become the key instruments of Singapore public policy and smart government. The nation’s 65 statutory boards also have the politically significant role of efficiently delivering needed public services.29 Their importance is boosted by Singapore’s lack of an elected local government that is autonomous from the national government.30 Together with para-political organizations like the community centers and town councils, the statutory boards thus constitute a sensitive yet nominally apolitical mechanism for identifying mass public needs and efficiently satisfying them.

Imbued with a persistent sense of crisis owing to Singapore’s turbulent history and fragile international position, its leaders have focused on innovation as a guiding principle of governance. As Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong put it in August 2012, “In a rapidly changing world, Singapore must keep on improving, because if we stand still, we’re going to fall behind … if we adapt to changes and exploit new opportunities, we will thrive.”31 The functionally oriented, technocratic, and implementation-focused statutory boards are institutionally configured to meet this imperative for managing the affairs of state efficiently and flexibly, particularly in support of rapid socioeconomic development in troubled times.

The statutory boards are attractive to Singaporean leaders for two other major reasons.32 First, they reduce the workload of Singapore’s career civil service, thus allowing it to remain smaller, more exclusive, and more capable of flexible, rapid response than would otherwise be the case. In addition, since statutory board salaries are often better than those of the civil service, and working conditions more flexible, the boards also reduce the brain drain from government-related institutions into the purely private sector, putting Singapore’s best minds to work on its most pressing socioeconomic problems.

Although Singapore’s statutory boards are quite unique in comparative context, especially in the way they are used to sidestep politicization of public policy, they do have some rough equivalents elsewhere in the industrialized world. One rough parallel is the independent commissions of the United States, such as the Securities and Exchange Commission, Federal Trade Commission, Interstate Commerce Commission, and so on. Independent regulatory bodies in Europe and Japan, such as the Federal Financial Supervisory Authority (Ba Fin) in Germany and the Financial Services Agency (FSA) of Japan, also have some similar functions, centering on the supervision of banks, insurance companies, and financial-service institutions, as well as investor protection. The Singapore statutory boards, however, administer as well as regulate and are much more salient in the overall national-policy apparatus than in major industrialized nations elsewhere. They also enjoy greater continuity of key personnel, owing to the high salaries and favorable working conditions provided to their key employees.

The Smart State in Its Human Dimension: Minimalist Government, Bureaucracy, and Its Meritocratic Recruiting Practices

To reiterate, the perceptiveness and responsiveness of Singapore policymaking are by and large products of four key factors: (1) an apt organizational structure; (2) high-quality personnel; (3) predictable regulatory parameters, especially the rule of law; and (4) timely technical innovation, such as e-government. The first three qualities prepare the ground for the fourth—the essence of smart government as it is conventionally conceived of late. Holistic decisionmaking mechanisms such as the statutory boards evolved in the early postcolonial days. They would be ineffective today, however, if the Singaporean smart state had not learned to recruit and use able personnel to staff them and the ministries that supervise them.

The overall structure of Singapore’s bureaucracy, as well as its recruitment practices, greatly augments the Singapore leadership’s ability to efficiently manage a complex, ambitious policy process at relatively low cost and with limited manpower. Despite originating in the colonial civil service, more recent incarnations are far more focused on both social needs and efficiency—the result of five decades of fine-tuning. The Public Service Commission (PSC) is a case in point: although established by the British in 1951, the PSC’s merit-based recruitment system was created in 1961, only two years after self-government, with many of the statutory boards also founded or restructured around the same time. Today, after more than five decades of curbing bureaucratic expansion, the country has less than 141,000 public officials, who constitute only 4 percent of the workforce.33 They are divided into two categories: “civil” servants, numbering 82,291 in 2014, who man the 16 government ministries; and “public” servants (58,574), who serve with the 65 statutory boards.34

This clear administrative division allows the government to differentiate in its recruitment and compensation practices between those who perform the formal tasks of government and those who conduct more politically charged and commercially related functions. To inhibit corruption—a bane of the developing world—Singaporean civil servants operate under extremely severe behavioral constraints and reporting requirements. They are, however, compensated with high salaries, those for high-level officials reaching well over S$1 million annually.35 Public servants at the statutory boards are recruited from broader backgrounds, often including the private sector, and operate under somewhat different, generally more market-oriented, incentive systems than their erstwhile bureaucratic colleagues.

To secure the very best candidates for both the civil service and the statutory boards, Singapore’s government leaders spare little effort. Able candidates are typically identified as they finish secondary school, at around 17–18 years of age, just before their A-level examinations. They are then offered all-expenses-paid scholarships to the best universities in the world, conditional on admission, in return for bonded 6- to 8-year commitments to government service. Upon graduation from Princeton, Harvard, Cambridge, and other elite universities in the world, these able young people are tested in Singapore government departments and agencies before being talent-spotted by supervisors. The successful candidates enter Singapore’s elite administrative service, consisting of only about 270 career officials. There they constitute the administrative core of the smart state, supervising bureaucrats affiliated with the government ministries and organs of state, as well as the employees of the statutory boards.36

Creating Small, Responsive Administrative Bodies with Broad Policy Concerns. Some concrete examples illustrate not only the integrated, holistic response of Singapore’s smart state, through the statutory boards, to outside developments, but also the creativity of its design. To address political-economic challenges, especially those arising from a lack of infrastructure, inadequate housing, and ethnic tensions, the Housing and Development Act was drafted and implemented in 1960. That law authorized the HDB and led to a sweeping transformation of Singapore’s housing situation. Whereas in 1959 less than 10 percent of Singaporeans owned their own homes, today that share exceeds 90 percent, with the overwhelming proportion of new homes having been built by the HDB itself.37

This board has also pursued an integrated approach to addressing a broad range of other social problems, not only the housing crisis but ethnic tensions as well. Its housing policies have not only generated a stake in society for Singaporeans through home ownership, for example, but they have also enhanced acceptance of ethnic diversity through measures that bring people of different backgrounds together as neighbors. Holistic Singaporean smart-state policies also provide citizens with individual Central Provident Fund (CPF) savings accounts that they can tap to buy homes.

When Singaporean authorities mandate the building of actual living spaces, they move beyond abstract thinking about policy to holistic planning and implementation that focus on how overall communities will realistically evolve. They design living spaces with multiple functions, making housing complexes self-contained and thus reducing energy consumption and time expended in commuting.

In addition to the HDB, Lee’s early team also created the Economic Development Board (1961), during a turbulent critical juncture that gave birth to the Singaporean smart state. The flexible and creative EDB developed a dynamic program of foreign investment incentives, going far to address the initial misgivings of multinational firms about Lee Kuan Yew’s fledgling PAP government. For more than half a century, the EDB, even now with less than 600 employees, has facilitated the systematic transformation of Singapore’s economic structure from labor-intensive manufacturing to high value added services. That key pillar of Singapore’s smart state, the entrepreneurial minister of finance, Goh Keng Swee, proposed the EDB and powerfully endowed it with a S$100 million budget,38 while Singapore’s per capita GNP still remained less than US$320 a year.39

During the 1970s, the EDB was instrumental in bringing Texas Instruments to Singapore, thus facilitating the emergence of a powerful local electronic-components manufacturing industry.40 Within a few years, the EDB was also spearheading the structural transformation from manufacturing to services, promoting Singapore as a “Total Business Center,” in which services were central. During the 1980s the EDB co-established institutes of technology and technological manpower training with German, Japanese, and French organizations, while also soliciting technology-oriented apprenticeships for Singaporeans with such global firms as Philips, Rollei, and Tata.

The EDB’s staff, drawn from the best of Singapore’s top bonded-scholarship recipients, is seasoned through extensive overseas on-the-job training at 21 international offices in 12 key countries worldwide.41 Its deployment often follows advanced graduate work in the best business and law schools of the world.42 The staff is organized into project teams, working intensively on priority cases, with a performance-oriented culture and incentive structure similar to those of U.S. consulting and investment banking firms like McKinsey or Goldman Sachs.

Smart government, as already discussed, not only builds new, socially and economically responsive institutions but also recognizes the importance of group dynamics within the subnational components of the state, such as Singapore’s EDB, HDB, and other statutory boards. It works to refresh important organizations by bringing new faces into key roles within them, as catalysts for change, instead of following more static seniority-based promotion systems. At the same time, smart government fosters networks between the vigorous young and their knowledgeable seniors.

Vertical Networks: The Principal Private Secretary System. Another distinctive Singaporean practice that has augmented the effectiveness of core leadership and enhanced the smartness of governance more generally is Lee Kuan Yew’s system of principal private secretaries (PPS). From the early days of his prime ministership and throughout his leadership career, Lee handpicked young, energetic officials whom he considered particularly promising and mentored them personally as members of his private staff. Then Lee sent these talented “leaders in embryo” out into a variety of strategic and challenging positions across the government, often in a variety of fields, to hone both their general management skills and their holistic consciousness. Lee continued to interact with his PPS alumni personally and to follow their development once they left his staff. Heng Swee Keat, for example, served first as managing director of the Monetary Authority of Singapore (2005–11), and subsequently as minister of education (2011–15), then as minister of finance (2015–16).43 Leo Yip, Lee’s PPS during 2000–02, served as permanent secretary of the Ministry of Manpower (2005–09) and chair of the Economic Development Board (2009–14) before becoming permanent secretary for home affairs in 2014.44 Such personal protégés of top leadership, and the relationships they build, are the very sinews of a state based structurally on institutions, but augmented by intricate personal networks linking and transcending those organizations themselves.

Building a Smart Foreign-Policy Structure

Astute foreign-policy responses to early challenges from abroad, such as developing close but not exclusive diplomatic relations with the United States, were crucial in building the institutional framework of Singaporean smart government. In doing so, Singapore conformed to Joseph Nye’s admonition that smart power should include both “hard” and “soft” power in complementary dimensions.45 On the hard side it developed a highly trained and well-equipped military, while on the soft side it stressed public diplomacy, exchange programs, development assistance, disaster relief, and military-to-military personal contacts.

The international challenge that Singapore’s leaders faced on independence in August 1965 was an existential one for their fledgling nation, coming just months after U.S. combat troops began pouring into South Vietnam. That challenge was compounded by domestic fragility, including stubbornly persistent double-digit unemployment. Upon independence, Singapore thus faced a critical juncture abroad, as at home—indeterminacy amid crisis, with institutions still fluid, in circumstances where leadership decision was crucial.

Response from Lee and his colleagues was not wanting. And it came in a characteristically pragmatic and nonideological form, on both the international and the domestic fronts, that took the perceived reality of a dangerous, changing world as a disturbing given. Lee persistently used Toynbee’s “challenge and response” concept and his own “survival motif” to cajole Singapore’s trade unions into cooperating with his policy design.46

Overseas, Singapore strengthened its ties to regional neighbors, to Israel, and ultimately to the United States, even as it proclaimed itself a member of the nonaligned movement. Domestically, Lee and his team aggressively pursued economic growth. They did so particularly through a neoliberal agenda of low taxes and foreign-investment incentives, while also intensifying their high-tempo program of public housing expansion.

Emulating Israel. The progression of Singapore foreign policy immediately after independence clearly illustrated both Lee Kuan Yew’s pragmatism and some important divisions among his subordinates, which ironically enhanced the country’s tactical flexibility. Singapore’s first overtures in political-military relations abroad were to neutralist Egypt and India, championed by Foreign Minister Rajaratnam, but they were rejected. In short order, Singapore approached Israel, whose strategic circumstances Lee himself regarded as quite parallel to Singapore’s own.47 Both, he noted at the height of Konfrontasi in the mid-1960s, were small nations, surrounded by larger, implacable foes.

Confronted with a hostile regional environment, Israel had “leapfrogged” its region to align with Europe and America. Lee believed that Singapore needed to perform a similar strategic feat, adding Northeast Asia to its range of prospective interlocutors as well. Tactically and operationally, Singapore needed to turn itself into a “poisonous shrimp,” too tough and heavily armed to be easily digestible by neighboring adversaries, including Sukarno’s Indonesia.48

Given Lee’s strategic vision, Goh Keng Swee, who on independence had volunteered to move from finance to defense minister, quietly contacted Mordecai Kidron, the Israeli ambassador in Bangkok, for help. On August 9, 1965, only days after the breakup with Malaysia, Kidron flew into Singapore from Bangkok to offer Israel’s assistance with military training.49 Over the ensuing years, Israel provided invaluable assistance to the Singaporeans, arming them with Soltam mortars and other weapons while advising them on combat doctrine (the “Brown Book”) and military-intelligence structure (the “Blue Book”).50 Its advice included a valued threefold prescription for military manpower recruitment: mass conscription for national service, plus a professional military and a large ready reserve.51

Characteristically, the leaders of Singapore’s smart state kept their strategically important relations with Israel discreet while simultaneously exploring potential alternatives. Singapore did not conclude formal diplomatic relations with Israel until 1969 and never established a full mission in either Tel Aviv or Jerusalem.52 Meanwhile, Lee’s foreign minister, Rajaratnam, continued to cultivate Afro-Asian neutralists, many of them bitter opponents of Israel, and even formally affiliated Singapore with the nonaligned movement in 1970.53

Behind this complex, two-track approach to Israel and the Islamic world were very real differences among Singapore’s top leadership, which in combination with Lee Kuan Yew’s pragmatism ironically enhanced the country’s tactical flexibility. Foreign Minister Rajaratnam was vocally critical of Israel and sought internally to have Israel condemned for its attack on neighboring Arab states during the June 1967 Six-Day War.54 Defense Minister Goh Keng Swee, by contrast, strongly opposed that gesture, warning that the invaluable Israeli defense advisers would leave. It fell to Prime Minister Lee to resolve the differences by quietly overruling Rajaratnam.55

Multipower Diplomacy. The pragmatism and division of responsibility among Singapore’s leadership showed clearly in early dealings with regional powers, the United States, and ultimately China—the three long-term focal points of Singaporean diplomacy. As Konfrontasi with Indonesia subsided in the wake of Sukarno’s 1965 overthrow, Singapore began actively approaching its noncommunist neighbors, with Foreign Minister Rajaratnam, of Tamil origin, being one of the early catalysts for the formation of ASEAN in 1967.56 Prime Minister Lee, whose strong views had alienated many neighbors, stayed in the background, and all Singaporean leaders pointedly avoided associations with China.

Following independence, Singapore’s formal security ties were with the Five Power Defense Arrangements (FPDA) nations, including Britain, Australia, New Zealand, and Malaysia.57 Given Lee’s anticolonialism, his delicate ties with Malaysia, and Harold Wilson’s disinterest in Asia, however, this multilateral partnership could not satisfy Singapore’s fundamental security needs. Following Wilson’s 1968 decision to withdraw British forces from east of Suez, the strategic logic of close ties to Washington was clear, and Lee himself pursued it brilliantly, at a highly personal level.

Lee encouraged Richard Nixon to talk with China, in the hope of a breakthrough.58 Meanwhile, Nixon’s quest for gradual redeployment of U.S. forces away from Southeast Asia, without full withdrawal, coupled with enhanced American dialogue with the People’s Republic of China, paralleled Lee’s own strategic thinking.59 And Lee continued a tradition of direct personal diplomacy—invaluable for Singapore’s global standing—with every succeeding U.S. president through Barack Obama.60 Little Singapore, with less than 6 million people, has consequently enjoyed some of the most unfettered and productive Oval Office access over the past half century of any nation in the world.

Lee Kuan Yew’s Personal Touch. Lee’s personal diplomacy also forged invaluable ties with China, Singapore’s other major interlocutor, in an era when suspicion of China in Southeast Asia was high. Lee invited Deng Xiaoping to Singapore in October 1978—a fateful meeting that helped lay the groundwork for Deng’s historic Four Modernizations, and for the positive development of Sino-American relations following the Carter administration’s normalization with China in January 1979.61 Singapore was not to normalize its relations with China until late 1990—a month after Indonesia did so, honoring a commitment to its ASEAN colleagues to be the last to establish ties with Beijing. Yet the personal ties that Lee developed with Chinese leaders were invaluable. Lee continued this pattern in personally helping to bring Chinese vice president and presumptive future leader Xi Jinping to Singapore at a crucial stage in Xi’s career during 2010.

Second-Phase Challenge: Surviving and Thriving in a Knowledge-Intensive Global Economy

The first phase of Singaporean smart-state evolution (roughly from 1959 to 1990) had centered on state formation and consolidation: on building the basic, holistically oriented infrastructure of both smart government and the broader economy. As the years of Lee Kuan Yew’s long formal stewardship over this period drew to a close, an elemental new challenge for Singapore was emerging that demanded smart capacities in a different sense. Revolutionary changes in telecommunications and finance, followed by the waning of the cold war, gave rebirth to a truly global political economy for the first time in nearly a century. The volatile, complex, technically sophisticated, and rapidly changing world presented an extraordinary mix of danger and opportunity that made capitalizing on the Digital Revolution indispensable to Singapore’s survival and prosperity. The escalating pace of technical and geopolitical change created its own new dangers alongside fresh opportunity. Thus in the second phase of Singaporean evolution the leadership faced the difficult task of updating and refining the Lion City’s institutions and strategies in order to confront the digital age.

In responding to these new challenges, Singapore chose to become knowledge intensive—both economically and in terms of state structure. To this end, it pursued the “postindustrial” socioeconomic paradigm, popularized by sociologist Daniel Bell and based on the principle that knowledge and ideas generate more wealth than the conventional manufacturing-based economy.62 Industry still did have some place, but in a more information-intensive form. Automation, cybernetic feedback systems, and computer-aided processes were growing increasingly important as an era of the Internet of Things began to dawn.

During the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, the political-economic challenge for Singapore’s founders was clear: devising institutional frameworks suitable for an industrial age (see table 3-1). With this given framework and infrastructure, Goh and Lee Hsien Loong, Singapore’s second and third prime ministers, were able to refine the smart institutions created under Lee Kuan Yew and to recondition them for a knowledge-intensive and more thoroughly globalized new era. Although the challenges of the 1990s and 2000s diverged from those of previous years and required different policy responses, Singapore now had in place a basic framework of smart institutions, with their open, holistic bias, that had generated the more technically oriented policies and ensuing economic success of the 1970s and 1980s.

Singapore’s later leaders shared a common institutional ethos with its founders: featuring a pragmatic and quick response to challenges, collaboration, and a willingness to assume substantial risks in order to realize long-term reward. The new leaders also saw the importance of stable, consistent parameters for business activity, including respect for the rule of law. In redefining and adjusting their institutions along these lines, Singapore’s leaders ensured that their paradigms remained relevant in the 21st century.

After an extraordinary 31 years at the helm of government, Lee Kuan Yew retired formally as prime minister in November 1990, to be succeeded by his trusted deputy, Goh Chok Tong. Lee nonetheless continued his direct involvement in policymaking, first as senior minister (1990–2004), and then as senior minister mentor (2004–11), continuing to help build Singapore’s smart state. As Lee ceded formal authority to Goh, Singapore entered a significantly different leadership era, marked by a changing, increasingly volatile political-economic world.

Table 3-1. Singapore’s Economic Transformation and the Evolving Challenges

1960s (labor intensive) Develop basic industrial facilities, infrastructures, and amenities Industrial development located away from residential areas Heavy industries do not affect the population significantly |

1970s (skill intensive) and 1980s (capital intensive) Clean and light industries: factories developed within residential areas Workers in residential areas tapped to support industrial activities Minimal travel for workers because of integrated work-residential complexes |

|

1990s (technology intensive) R&D focus Mixed-use development Technology/science parks created to facilitate research, develop prototype, and enhance market reception |

21st century (knowledge intensive) Knowledge industries Clustering and integration Sectoral focus on biomedical research, IT, and multi-media development (for example, Biopolis, Medianopolis, and Fusionopolis) Work, live, play, and learn environment: ex- one-north, create land use intensification; ex-urban farming, multistory factory complexes, underground space usage |

|

Key factors for success? Ability to —Initiate and implement multiprong, interministerial economic strategies and policies in integrated, pragmatic, and effective fashion —Develop necessary infrastructure and facilities to respond quickly to new requirements —Identify new economic drivers quickly —Identify and rapidly adapt to emerging challenges, utilizing stable, transparent legal parameters |

||

Source: Er Tang Tak Kwong, CEO and president of Jurong International, “Sustainable Industrial Development in Singapore,” presentation at the World Bank, October 7, 2010 (http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTURBANDEVELOPMENT/Resources/336387-1286571882293/Tang.pdf).

Goh approached the new challenge of leadership with a deeply ingrained sense of duty and integrity. When he was nine, his father died of tuberculosis, and Goh played a key role in raising younger brothers and sisters, in support of his widowed mother.63 He spent more than eight years in the private sector, at Neptune Orient Lines, which honed his pragmatic sense; there he associated with many wealthy entrepreneurs, such as Y. K. Pao of Hong Kong. Yet Goh was never corrupted by their flamboyant lifestyle and served as a paragon of the able, principled, and at the same time self-sacrificing young official aspiring with other early leaders to build the smart state.64 Indeed, young Goh’s life story and clear ability so attracted Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew on Goh’s return from graduate study in the United States (Williams College) that Lee actively recruited Goh as his principal private secretary.65

Goh’s Tenure and the Smart State’s Evolution: Provoking Innovation, Improving Citizen Access, and Inhibiting Clientelism

To Goh Chok Tong, a fundamental task of government was to be socially responsive. Focusing on popular needs, he allowed fresh ideas and people to freely enter politics, short-circuiting the rigidities and distortions of personal gain, thereby enhancing direct citizen access to the mechanics and output of state power. Electronic government, with the transparency it spontaneously provided, coupled with anticorruption provisions codified in law were central elements in this new equation.

Introducing Electronic Government. One of Singapore’s smartest moves, illustrating its responsiveness to new technology, was to wholeheartedly embrace electronic government during the 1990s and 2000s. Today almost every government service is provided online: driver’s licenses, export-import authorizations, and documents establishing corporations, just to name a few. And these services are provided quickly and transparently—one key hallmark of an authentically smart state.

Electronic government in Singapore has one of the longest pedigrees of any such service in the entire world, dating back to 1982 with the advent of the Civil Service Computerization Program.66 E-government’s journey in Singapore began just as the global information revolution itself was dawning, with the goal of transforming Singapore’s government into a world-class user of information technology.67 Thereafter e-government proceeded in three phases, gaining particular momentum and strategic orientation during the 2000s.

The late 1990s saw the technical convergence of information technology and telecommunications, which naturally transformed the concept of service delivery in Singapore. This epochal technological transition paved the way for the e-Government Action Plan (2000–03), focusing on rolling out as many new government online services as possible.68 Among those now consolidated on the e-Citizen website are passport applications, school-fee payments, changes in personal Central Provident Fund allocations, income and property tax payments, information on Battle of Singapore historical sites, and even a portal to help parents monitor their children’s homework.69

The initial e-Government Action Plan was succeeded by a sequel (2003–06) that concentrated on improving the service experience of customers. Then came the i-Government 2010 Master Plan (2006–10) built on the foundation of its predecessors, which focused on mobile services, as well as on creating an integrated government that would work seamlessly behind the scenes to serve customers better. By 2015, 97 percent of Singaporean citizens and businesses expressed satisfaction with the general quality of these e-services.70

Over the past five years, Singapore’s e-government advances have won numerous international accolades. In 2015, for example, Singapore topped the Waseda University Institute of e-Government’s global rankings as it had for most of the previous decade.71 During 2014 it also ranked third in the United Nations E-Government Development Index, and second for online service delivery thanks to its new e-citizen portal, its on-inbox secured platform for receiving government electronic letters, and its continuing upgrades to mobile government.72

Capitalizing on these successes, Singapore has turned e-government into an export industry. A key element of this transition involved privatizing e-government activities under the auspices of a new para-public firm called Crimson Logic. The genesis of this new and important entity came in 1988 through a Singapore government initiative to develop TradeNet, one of the world’s first single-window systems to facilitate trade.73 Crimson Logic continued to grow and diversify into other areas of e-government, including health care and legal services, and into commercially based international operations in over 30 countries (for further e-government details, see chapter 6).74

Process Innovations. Goh also introduced important procedural innovations in Singapore’s political process, designed to enhance government responsiveness and thus to enhance smart government institutionally, as well as technologically. These changes included a system of nominated members of parliament, designed to introduce intellectual gadflies into the political process; group representation constituencies, intended to enhance the role of well-defined subnational communities; government parliamentary committees; and grassroots governing bodies (mayors and community development councils) to bring government closer to the people.75 A constitutional amendment providing for direct election of the president, while strengthening this individual’s prerogatives to include a review of possible abuses of power under internal security and religious-harmony laws,76 as well as corruption investigations, also enhanced political pluralism and the vibrancy of internal political debate.77 This change became effective shortly after Goh took office, so significantly influenced the politics of Singaporean policymaking during his tenure as prime minister and helped make the Singaporean state smarter in its response to civil society.

PAP candidates for election to parliament have traditionally ranked among the key leadership networks in Singapore. These people have been carefully vetted by senior Singapore officials, including prime ministers themselves, in a top-down process that leaves little to chance. Goh Chok Tong introduced a system of nominated members, not subject to election, to broaden the ranks of prospective parliamentarians, bringing academics and others with distinctive skills into leadership ranks, as already mentioned.

Nurturing Smart Institutions to Stay Globally Relevant and Competitive. In response to the globalization challenge, Goh Chok Tong’s policies gave birth to the National Computer Board; the major e-government one-stop portals; the CPF Edusave, Medisave, and Medifund programs; and the SIJORI Growth Triangle concept. A new Ministry of Information and the Arts was also introduced (1990) in keeping with Goh’s vision of making Singapore a “world-class Renaissance city” and “a nation of ideas” capable of staying globally competitive and relevant in the 21st century.78 In a departure from his predecessor’s more austere approach, Goh also supported establishment of a Speakers’ Corner in Singapore, modeled after London’s Hyde Park, quietly applauding “little bohemias” of this nature.79

With his quiet yet principled ability to lead, Goh efficiently navigated through the volatile global environment of the 1990s and early 2000s. He rallied Singaporeans during the Asian financial crisis of 1997, in the aftermath of the 9/11 attack on New York and Washington, and during the SARS epidemic of 2003. Goh left an enduring legacy for his city-state in the global arena—“a culture of greater openness and public engagement, as well as a higher international profile for Singapore.”80 He was assisted in these efforts by Senior Minister Lee Kuan Yew, who focused on projecting Singapore upon the broader world stage, capitalizing on his formidable range of international contacts while staying out of domestic issues and Southeast Asian regional affairs.81 Meanwhile, Deputy Prime Minister Tony Tan—a previous defense minister, Lee’s personal choice for prime minister, and Singapore’s future president—concentrated on both security issues and, anomalously, education policy.82

Lee Hsien Loong’s Efforts to Vitalize the Smart State Stress the Counterintuitive

On the wall of Lee Hsien Loong’s prime ministerial office at the Istana hangs an elegant scroll, as noted earlier, that bears the ancient Tang dynasty admonition: Ju an si wei, jie she yi jian (Watch for danger in times of peace. Be thrifty in times of plenty).83 It reflects perhaps the most important characteristic of the younger Lee’s leadership over the past decade and more: his persistent and systematic efforts to renew the smart state. He has done this by reexamining existing assumptions and reconfiguring even well-established and well-regarded policy approaches for the new century, with a special emphasis on technology. Although the elder son of Lee Kuan Yew, and one who clearly holds his father’s remarkable tenure in high personal regard, the younger Lee has adopted strikingly different approaches to governance and has been extremely successful in implementing his own novel approach.84

Lee Hsien Loong’s approach rests on the concept of mindset change. As Lee puts it, “We have to see opportunities rather than challenges in new situations, we have to be less conventional, we must be prepared to venture, and you’ve got to do this as individuals, we’ve got to do this as a government, and I think we have to do it as a society.”85 Toughened by years of military experience, he appears to be highly disciplined. Lee is also clearly pragmatic and attuned to following a realistic rather than an ideological course, in keeping with the traditional pattern of Singapore’s smart state.

The younger Lee has applied his penchant for counterintuitive thinking even to long-held tenets of his father’s policy approach. Where the elder Lee stressed unity and sacrifice, his son, despite his extended military background, has emphasized diversity and compassion for the less educated, the elderly, and the disabled.86 While his father was often regarded as authoritarian, Lee Hsien Loong has emphasized teamwork, while manifesting empathy to those of different, less privileged backgrounds.87 From the early days of his involvement in grassroots politics during the mid-1980s, he has been known as a reformer, alert to the dangers of popular disaffection with the sort of “macho-meritocracy” that Singapore was becoming.88

When he succeeded Goh in 2004, Lee Hsien Loong also explicitly stressed global competitiveness and positioning Singapore as a knowledge hub for the high value added segment of the world economy. This approach helped make Singapore an attractive destination for able, innovative foreigners, whom the younger Lee’s administration attempted to nurture with ambitious global cooperative projects and Singapore-based international research centers. Like his predecessor Goh Chok Tong, Lee gave strong priority to information and to the arts through such technically oriented vehicles as the Infocomm Development Authority of Singapore.89

Lee Hsien Loong’s emphasis on staying competitive by treating the challenge of globalization as an opportunity has enabled Singapore to survive and even thrive in a globalized era. Singapore strives today to achieve structural transformation toward a knowledge-intensive economy by enhancing its own role as a global knowledge hub and as a connector and catalyst among globally prominent institutions in its areas of special research priority.

The National Research Foundation (NRF), established in January 2006, less than two years after Lee Hsien Loong came to office, plays a key role in implementing this strategy. It provides appropriate research environments for entrepreneurs and researchers from throughout the world who are talented in creating ideas and inventions. The NRF seeks to translate the resulting research and inventions into commercialized products, by investing heavily in priority sectors and companies, leveraged by para-public firms like Temasek.

Various government bodies, including both the NRF and Temasek, work strategically to foster this future potential through diverse tools uniquely suited to their own state of development. At each stage of innovation and enterprise, entrepreneurs are provided access to a substantial level of support. Proof-of-concept grants (from the NRF) and technology-gap funding (by Exploit Technologies Pte., Ltd. [ETPL], for example) have been established to help entrepreneurs with conceptualizing ideas and prototyping. Government support continues into the early and volume-expansion stages of the product life cycle through programs such as the Sector Specific Accelerators Program and Early Stage Venture Funding schemes.90 The government also strives to create a base level of innovative capacity through programs such as the University Innovation Fund for Entrepreneurial Education, supported by the NRF. The overall goal is to promote a steady progression from the conceptualization to the commercialization of ideas, and then to economic growth. Ultimately, the micro-level objective is to prepare firms for initial public offerings and conclusive judgment by the financial markets.

Beyond his research and development emphasis, the younger Lee worked to integrate Singapore more deeply into the global economy by strengthening the global free trade regime and thus crafting a larger market in which Singapore could grow. Goh Chok Tong, to be sure, concluded the landmark U.S.-Singapore free trade agreement, just before leaving office in 2004. But it was Lee who subsequently concluded free trade agreements with some of the largest economies in the world, including India (2005), China (2008), and the European Union (2012). He also successfully managed a major economic crisis when the Lehman shock of 2008 sent Singapore’s economy into a tailspin, imposing painful losses on the city-state’s global investments.

Lee’s initiatives to stay globally competitive have worked to make Singapore an attractive destination for foreigners across many facets of the economy. Lee even authorized the opening of two new casinos in 2005, merely a year after taking office. Pointing out that there were already 13 casinos on and around the nearby Indonesian island of Batam, just 45 minutes from Singapore by high-speed ferry, with many more in Malaysia, Macao, and other neighboring areas, he asked pragmatically why Singapore should reject an activity attracting so many wealthy Indian and Chinese tourists.91 At the same time, he did respond to criticism by religious leaders and others by insisting on a prohibitively high entry fee, which discouraged gambling among those of modest means who might otherwise waste hard-earned family income on this activity.92 Lee’s pragmatic, open style was also reflected in his willingness to introduce F-1 auto racing into Singapore: in 2008 the narrow streets of Singapore became the site of the first nighttime F-1 race in the world.93

The Smart State as Provider of Stability and Social Protection

During its early days, the central responsibility of Singapore’s nascent smart state was twofold: to provide a stable framework of rules for economic development, and to supply low-cost yet enabling forms of social protection. This hybrid approach continued under succeeding leaders, as it had under Lee Kuan Yew. Both Goh Chok Tong and Lee Hsien Loong pursued pragmatic policies that cut across the left-right ideological divides that have so polarized Western welfare states.

As prime minister, Goh introduced a broad range of creative policies focused on combining improved economic efficiency with broad social-welfare coverage. These innovations he labeled his “Next Lap” initiatives and, in an updated format, “Singapore 21.”94 Among the novel yet socially sensitive approaches were Edusave, a tax-advantaged savings program to aid with education expenses, including enrichment programs; Medisave and Medifund, to help both average citizens and the needy with medical payments;95 the Vehicle Quota System for controlling overcrowding on the highways; and important upgrades to the HDB housing program.96 In international affairs, Goh undertook important initiatives in East Asian regional relations, including the SIJORI free economic zone Growth Triangle agreement with Indonesia and Malaysia (1994); the Suzhou industrial park agreement with China (1994); and free trade agreements with Japan, New Zealand, Australia, and ultimately, in April 2003, with the United States.97

Singapore’s Distinctive Leadership Style, and the Evolving Smart State