‘I had four children in the 1950s and 60s and never questioned the process. My family doctor gave me an approximate due date and told me what to eat, and that was it, until the deliveries. I went into each birth blindly – the system was foreign and scary. Dilation, effacement, transitions… I learned about those things 30 years later when my grandchildren were born. I didn’t know I had the option NOT to have drugs. It is with great sadness that I think back on what giving birth could have been like for me, if I had had the information my daughters have today.’

MEREDITH, 70, MOTHER TO FOUR GROWN DAUGHTERS AND THREE GRANDCHILDREN

FIVE THINGS TO KNOW ABOUT YOUR OPTIONS

Knowing your options – and using them – will make a huge difference to how this birth turns out.

You can choose:

Most of us spend more time choosing where to go for our summer holiday than we do when deciding where, how, and with whom we’ll give birth to our babies.

When it comes to this earth-shattering, once in a lifetime, fundamentally crucial event we are, in general, a bunch of fatalistic, ill-informed chancers. When you think about it, this is probably a little ill-advised.

Most of us (particularly first time around) trot along to the GP when we get pregnant and trundle obediently through the ‘system’. What we get there depends on largely on our postcode and circumstances. This is not surprising, really. It’s hard to have an opinion if you haven’t seen the inside of a maternity ward since you came out in one, so going wherever the GP sends you and accepting whatever care is arranged for you is certainly the easiest thing to do.

It isn’t necessarily the wisest.

Maternity care is subject to exactly the same variable standards as any other kind of health care in Britain. Hospital policies vary. Staff attitudes, motivation and outlook can be radically different from unit to unit. But within this seemingly concrete system lurk a wide range of options for childbirth. If you are well-informed you can make the sort of choices about, and during, labour that will help you handle it fantastically wherever you are, whatever happens and whatever health care professional is with you.

This chapter will show you what your options are. It’s time to start making some serious choices about this birth.

A WORD ABOUT CONFIDENCE | If you walked into Jigsaw, stood there while the shop assistant bossed you around, squeezed you into a dress you hated, told you that no, you couldn’t have the one you wanted, then sent you packing after painfully separating you from a large amount of money you’d feel pretty dissatisfied, if not distressed, about the whole thing. Now, childbirth, of course, isn’t shopping. It’s nothing like shopping. But it’s astounding how we’ll abnegate responsibility for birth in a way we’d never dream of repeating in any other area of our lives.

This isn’t about personality. Or even self-confidence. You may be a red-blooded demon in the boardroom and the most assertive shopper ever to darken the door of Harvey Nicks, but when it comes to making decisions about who’ll do what to your body and baby during labour, you could well crumple if you’re not truly informed.

Part of the problem here is the tendency many of us have to be self-effacing when it comes to medical matters. It’s like they’re totally beyond us. Nothing to do with us. Scarily difficult. Absolutely not our responsibility. Julia encounters this attitude a lot. Her clients often don’t want to rock the boat during pregnancy; they don’t want to tie up their midwife or doctor with too many questions, or appear to think of themselves as a ‘special case’, or presume to ‘interfere’ with the doctor’s job. Psychologists have found that feeling respected by staff and treated as an individual during childbirth are crucial factors in deciding how we feel about it later. But there’s no way you can be an active participant if you don’t have the first clue about what you’re doing.

‘I was so disempowered during the birth,’ writes Tanya, mother of Amelie (2). ‘I never felt that I could make any decisions of my own despite a good degree, a career and birth preparation etc.’ Part of the problem here is that it’s not easy to be assertive with a baby bearing down on your perineum. This is why you have to make the bulk of your decisions before you are in labour. Understanding your hospital and having a birth partner who can really support you, as well as a good grasp of what might happen and what you’re going to do about it, will all help you feel ‘empowered’ – even when you’re on hands and knees grunting like a wildebeest.

A WORD ABOUT SAFETY | You probably assume that going for the hospital closest to home is the only ‘safe’ or ‘reasonable’ option for this birth. It isn’t. You probably assume there’s no point in making choices about how you’ll cope in labour because you don’t know what it will be like, and anyway, the medical staff will tell you what to do. This is not the case. You may believe that making active choices about where, how and with whom you’ll give birth is possibly risky and almost certainly futile. It isn’t. Trusting your health care team, feeling comfortable and safe in your hospital (or at least understanding why, if you don’t) and feeling genuinely informed about what’s happening are the foundations of a good experience of childbirth. If you ignore this stuff and bumble along doing what you’re told, things may turn out OK on the day. But then again, they may not. Do you really want to chance it?

MAKING PROPER CHOICES: SOME QUESTIONS THAT NEED ANSWERING

If this is not your first baby, you’ll be tempted to skim this chapter or skip it completely. Fair enough: you certainly do know a lot more than you did last time. Studies have shown we are generally better at coping with childbirth if we’ve done it before. But this does not mean you should stop making choices. No two births are the same. If a strategy didn’t work in your last birth, it may well work in this one. I didn’t touch the birth ball during Sam’s birth but spent my entire labour leaning on it with Ted. (I didn’t even know what a birth ball was with Izzie.) Whatever you do, don’t narrow your options through ignorance or apathy.

Make a list of the choices you made in your last birth then rate your own satisfaction with each.

Take this list to your midwife (and to Chapter 7 to turn it into your birth plan) and discuss (and research for yourself) alternatives to the bits you didn’t like, or ways to handle them. This will help you make active, meaningful choices, not knee jerk or pointless ones.

Control freaks beware. Our message here is subtle, but vital: you can’t control this birth completely no matter how many excellent choices you make. Your baby (or body) may have different ideas on the day, and you’ll have to deal with the unexpected. You can, however, feel more in control – and at least influence events for the better – if you’re making good choices. Your options, then, start here, and are ON GOING.

It all sounds like a lot of work. But many women report that a feeling of ‘helplessness’ was one of the most upsetting aspects of giving birth. Professor Josephine Green, a psychologist specialising in women and childbirth at Leeds University, has studied the psychological effects of women’s sense of control during childbirth1. ‘Our studies have found that feeling in control – particularly about what staff are doing to you – is a major factor in how good women feel about the birth afterwards.’ Since how you feel afterwards has been linked to post traumatic stress disorder and postnatal depression (both of which will affect how you mother your infant), it’s not some middle-class indulgence to care.

You may think you want to give birth with only endorphins for company, then end up choosing a buttock full of analgesia. Or you may decide to get an epidural at the first twinge only to end up coping brilliantly without a needle in sight. ‘I thought I wanted a water birth,’ says Janet, 33, mother of Clea (3) ‘I fought so hard to get it (I have herpes and my doctor wanted to give me a caesarean). But on the day I’d rather have cut off my own hand than get into that pool: I gave birth on the hospital bed without having so much as dipped my big toe in the water I’d fought so hard for.’ Many of us, largely through nerves, become shackled by preconceived ideas about the way we want things to go (‘I simply WILL not allow anyone to break my waters/give me drugs/operate on me’). Try not to do this. Instead, see your options as a process that will be on-going throughout pregnancy and labour.

HOW TO MAKE MEANINGFUL CHOICES

Ultimately, the choices you explore in this chapter will become a flexible birth plan. We cover how to write one in Chapter 7: Expect the unexpected.

‘Trying to control birth is futile: you can’t control it. Trying to do so just sets you up for failure,’ says Jessica, mother of Tyler (2) and Bea (1). Jessica is not alone in thinking this. And she’s also right – up to a point. Going with the flow is vital during childbirth. But going with the flow blindfold, possibly in a panic, alone, in pain and fear and at the mercy of a hospital system you don’t understand is clearly not your best strategy. You may not be able to change medical events, but how you handle them can make the difference between a horrifying ordeal and a series of decisions and coping techniques. One study2 in 2001 found that the main factors that influenced how we feel about labour are:

You can influence all of these things.

One thing women repeatedly said about their first births, when we spoke to them for this book, was ‘If I’d known then what I know now…’. You might think it’s sensible not to think too much about the details of birth. We’re all tempted to do that. But ignorance, when it comes to childbirth, is not bliss. Here’s a run down of the things you should be making active choices about right now.

Even if you have no intention of going anywhere other than your local hospital, a bit of research will help you understand the ethos of the place: if you know the beast, you can plan how best to handle it.

HOSPITALS | Most of us think we’re doing this when we diligently traipse around on the ‘hospital tour’, pretending to listen while trying to blank out the unfamiliar smells and lurking medical equipment. Here’s how to use your tour effectively.

Tour tips:

Irritating things to ask on your hospital tour:

Changing hospitals: You actually have a legal right to choose where you will give birth. Ultimately, if you are really not happy with the hospital you’ve been referred to, you don’t have to lump it. Switching to a different hospital, investigating a home birth or going to a birth centre (see below) are not radical things to do as long as you have thought them through carefully and listened to any medical concerns the midwives or obstetricians have. As midwife Jenny Smiths puts it: ‘It’s really important to choose a hospital where you feel comfortable and secure and can trust the medical professionals to work with you. Switching to a different hospital is not always straightforward, but many people can do this if they try.’ If you can’t switch to a different hospital (perhaps because there isn’t one in your area), make sure you understand yours well, and are aware of any particular challenges you may meet there; this way you can plan how you will tackle them.

If your GP is unable (or unwilling) to refer you to a different hospital, talk to your Primary Care Trust (PCT). The best person to ask for your local PCT address is your GP’s practice manager.

Further reading:

Dr Foster’s Good Birth Guide (Vermilion, UK, 2002). Written in consultation with the Department of Health, the Royal College of Midwives, and the Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynaecologists, has the facts and figures about every maternity unit in the UK (also online at: www.drfoster.co.uk).

You’re Pregnant! is a localised magazine in 100 editions (available from your GP or midwife) which gives local information about maternity services in many areas of the country (try the information line 08701 555 455 if you can’t get hold of a copy).

Online:

www.birthchoice.co.uk has information on hospitals across the country, ranging from facilities to caesarean rates.

MIDWIFE UNITS | Sometimes called ‘birth centres’, ‘midwife units’ or ‘GP Units’, these will generally take you if you’re having a low-risk pregnancy. They tend to have a lower intervention rate than many hospitals and usually don’t have facilities for caesareans (so you’d be transferred to the hospital should you need one). They can be attached to a hospital, or in a separate building on site, or they may be in a different location entirely, but are usually relatively near a main hospital (in case of emergency). The facilities vary, but many are smaller and more ‘homely’ than hospitals. It’s worth having a look at your local one if it still exists (some units are facing closure because of midwife shortages). At one of these units you are more likely to be encouraged to walk around during labour and have access to a birthing pool than you are in a hospital: again, things that maximise your options for the birth. You will also probably have more control over your privacy in a midwife-led unit, than in a hospital. Having said this, some women say they didn’t get the ‘woman-centred’ approach they’d hoped for by going to a midwife-led unit. It’s also worth knowing that according to the latest NHS caesarean guidelines for health professionals, being in a midwife-led unit does not reduce your likelihood of having a caesarean.4 Units, like hospitals, vary. So ask the same kind of questions you would on any hospital tour.

PRIVATE BIRTH CENTRES | These are not common in Britain but they can be a great option if you’ve got the cash. They tend to focus on natural birth, are nice and plush, have extremely supportive and encouraging midwives and very low caesarean rates. But you’ll pay through the nose for this (still, some would argue that this is a better use of your money than that holiday in Barbados). At a London birth centre, for instance, a full package birth might set you back about £4000.

Where to go for help:

www.babycentre.co.uk has articles and information on birth centres in the UK.

GIVING BIRTH AT HOME | Only just over 2 per cent of British women have their babies at home. But these numbers mask some pretty hefty regional variations; in some parts of the country as many as 20 per cent of us give birth at home, in others, less than 1 per cent do. Much of this comes down to the attitudes of health professionals. Some doctors are reluctant to agree to home births and some midwife teams find it hard to cover homebirths because of stretched resources. If you decide you want to give birth chez vous – providing there is no compelling medical evidence that this would be a bad idea – you need to get the support of your midwives. If you give birth at home you want the best medical care available: experienced, trained midwives.

Lots of women say the first reaction of their midwife or doctor to their request for a homebirth was knee-jerk discouragement (with a hefty dose of scepticism). Often this will change when they realise you’re serious, reasonable and informed. If you end up (God forbid) having to fight for a homebirth, it’s worth knowing that you have a legal right to give birth at home (or indeed, anywhere you fancy).

Homebirth used to be a matter of necessity – hospitals were reserved for illness not childbirth. Then, with the early women’s movement, came the drive towards birth in hospitals. ‘It was a safety issue. To go from giving birth in your home to delivering in a clean doctor-run environment felt like a huge step in the right direction,’ says retired nurse Gloria Fleischer. ‘Back in the 1950s and 60s home birthing women were seen as crazy. We were even trained to strap the “natural birth” women down – to keep the other women from getting upset.’ Today homebirth is not the defiant option it once was. Research has shown that for a healthy woman having a straightforward pregnancy, homebirth is as safe as hospital birth. Many midwives are highly experienced at homebirth and will encourage it, where appropriate. They bring with them medical equipment including gas and air (for pain relief), equipment to resuscitate the baby in the unlikely event that something should go wrong, and a suturing kit, to give you any stitches you might need when the baby is out – unless your tear is severe, in which case you’ll need to go to the hospital.

Neither are the practicalities of a homebirth as daunting as you’d think. Your midwife gives you a list of things you’ll need for the birth, including plastic covers for the carpet and things like towels and food for you to eat in labour. You call the midwives when you go into labour and one will come out and see you.

Homebirth certainly isn’t for everyone, but if you are ‘low risk’, confident and live within easy reach of a hospital (should you need to transfer to one), your home can be a very reassuring place to give birth. As Sarah, 36, mother of Leo (born in hospital) and Harry (born at home) puts it: ‘Being at home made me feel in control and relaxed (once we had dispatched the builders!) and helped the birth to be straightforward. Harry was born in a pool in the living room. I was so comfortable in the water that my contractions quickly became very strong. The last ten minutes with no pain relief were absolute agony but delivering him and keeping him in the water were beautiful. The three of us got into our own bed afterwards – it felt so much more civilised than being in a noisy, dirty hospital ward.’

Wot, no epidural? You can’t get an epidural at home. If this is worrying you, you may not be the best candidate for a homebirth. Though you can get a prescription for injected analgesia such as pethidine or meptid (see page), some midwives will tell you that if you think you are going to need drugs in early labour then you shouldn’t go for a homebirth.

Is it safe? There are some scenarios in which hospital births are certainly your best option, such as if you’re having twins, a breech baby, or if you or the baby have certain medical complications. Your own inclinations are also important. If you’re scared of birth, think it’s inherently dangerous or risky and worry about medical safety issues or getting hold of drugs, then hospital may be the place for you. But if you believe that birth is a safe, normal event, feel comforted and safe in your own home, trust your midwives, don’t have any medical complications and live relatively near the hospital then it might be something to consider.

How to make up your mind about homebirth Homebirth isn’t a panacaea and your birth can be fantastic regardless of your location, as long as that location suits you. Some women choose homebirth out of bitter defensiveness, often after a bad first experience (‘I’m not letting those evil doctors anywhere near me this time’). If you feel this way, and you end up having to transfer to hospital again, you’re not going to be exactly calm and reconciled.

IF YOU’RE THINKING ABOUT HOMEBIRTH ASK YOURSELF:

Remember you can always plan and prepare for a homebirth but then decide, on the day, to go into the hospital. Nobody is going to penalise you for changing your mind.

Pressure from others NOT to have a homebirth From the moment you suggest you might like to give birth at home you’ll start hearing alarmist stories. Julia has seen this on many occasions: ‘One of my clients had a mother-in-law who was a retired nurse. Every phone call or visit the mother-in-law would tell long gruesome stories about babies that would have died if not for the miracles of medicine. Pregnancy is a time when we are sponges – especially for emotional issues. Consider just keeping your birth plans between you and your partner. Nobody needs to know where your baby will be born, and after the fact nobody will care.’ The only thing that really matters is that you make a sensible, informed choice after serious thought and discussions with medical professionals.

Where to go for help:

Association for Improvements in the Maternity Services (AIMS) offer information about your rights and publish a leaflet Choosing a Homebirth. www.aims.org.uk or call AIMS 0870 765 1433.

Further reading:

Birth Your Way: Choosing Birth at Home or in a Birth Centre by Sheila Kitzinger (Dorling Kindersley, UK, 2002). An updated book about making confident choices beyond your local hospital.

Homebirth – Information to help you decide (2002), a booklet published by the National Childbirth Trust. Available from NCT Maternity Sales. 0870 112 1120 Email: sales@nctms.co.uk. www.nctms.co.uk.

Online:

Our website has more on homebirth (www.bloomingbirth.net)

Homebirth Reference Site has lots of information – www.homebirth.org.uk You can also find peer support in ‘Homebirth meet up groups’ around the country. www.homebirth.meetup.com.

It’s impossible to overestimate how important your health care team will be to this birth. A midwife can become a god-like presence for you in labour: your mother, sister, guru, spiritual leader, teacher, professor rolled into one pragmatic, competent bundle. It is important that you’re able to discuss your worries and concerns openly with the midwife you see most during the pregnancy, and feel she’s listening to you (Chapter 3: Fear and Pain spells out why). But she probably won’t be with you during the birth itself.

There are many different types of midwife care in this country, and it’s a really good idea to understand how your care is organised so you can get the best out of it. Get your midwife to explain exactly how her team works (and write it down for yourself, or you’ll forget the minute you walk out of her office).

THREE DIFFERENT TYPES OF MIDWIFERY/HOSPITAL CARE | Yours may not work exactly this way so ask for an explanation.

1. Shared care: a community midwife and your GP see you during pregnancy and a midwife at the hospital (you may not have ever met her) will attend the birth. You may have a check up or two at the hospital, and will go there for any scans. If you take a violent dislike to your community midwife (and feel this is jeopardising things for you) first talk to her about why you’re finding it difficult, then ask to transfer to another team or speak to the senior midwife in charge of community midwifery. Don’t just grin and bear it.

2. Team midwifery: a smallish team of midwives will see you during pregnancy and labour and you have a greater chance of getting to know the midwife who’ll end up attending your birth.

3. Domino scheme: a midwife you’ve seen during pregnancy actually attends your birth.

MIDWIFE SHORTAGES | The Royal College of Midwives estimates that Britain is short of around 10,000 midwifery staff. One of the main effects of this is that you may not be cared for by the same midwife during the whole birth (shift changes happen) and those you do see in labour are likely to be strangers to you. They’ll also probably be somewhat overstretched. Some midwives say that on a full moon (yes, really) bedlam descends on the maternity unit. But even if the moon is not full, the chances are that your midwife will be looking after at least one other woman (and sometimes more) at the same time as you during your labour. Usually, she’ll time things so that she can be there for you when your labour is hotting up (and, obviously, for the delivery itself). But many of us do have relatively long periods of being left alone with only a midwife popping in from time to time to make sure we’re OK.

‘OK’ is, of course, a relative term when you’re having contractions. What may seem fine and normal to a trained medical professional may appear extremely unreasonable to you. One recent study5 found that 13 per cent of women who’d given birth before, and 16 per cent of first timers, said they were left alone in labour at a time when it worried them to be alone. This is a pretty convincing reason to have some other form of support sorted out (see Chapter 9: The Love of a Good Woman). It can get lonely, worrying and dispiriting if it’s just you, your contractions and your increasingly knackered partner rubbing away helplessly at your back.

‘Try and become part of the team rather than a frustrated outsider,’ advises midwife Jenny Smith, ‘Don’t be afraid to ask questions and find out basic information about the facilities on offer. But try to remind yourself that she’s not “abandoning” you – she has to look after other women and their babies just as she has to look after you and yours. Her biggest concern, on really busy days, is simply the safety of every woman and baby in the unit.’

A WORD ABOUT CONSULTATION… | There’s a lot of talk these days about how you should agree to, and understand, what’s being done to you by doctors and midwives. But even the most gung-ho among us can feel distinctly disempowered when juggling anxiety, pain, medical jargon and an expert who may not have a PhD in tact. If you’re facing a genuine medical emergency, full consultation might not be possible (they’ll be too busy helping you or the baby to check that you’re OK with this). But as a basic guide, don’t agree to any treatment, test or intervention, until you’ve had answers to the following questions:

CONSULTATION AT-A-GLANCE

When a test is suggested ask:

When a treatment or intervention is suggested (during pregnancy or labour) ask:

PERSONALITY CLASHES | If you are having ‘personality differences’ with the midwife try to resolve things (or get your partner to do this on your behalf). ‘If you feel your midwife’s approach is dramatically affecting the way you labour – for the worse – get your partner to pop out and ask to speak to the person in charge (this will be the coordinating or senior midwife),’ advises midwife Jenny Smith. ‘Be polite. Say something like, “I think we have a bit of a personality clash – would you please help us to sort it out?” Often it can just be a case of misunderstanding, and with good communication I have known women who have been extremely happy continuing with their original midwife after an initial hiccup.’ If, however, the problem really IS your midwife, it’s not a good idea to press on, fretfully, feeling bullied or unsupported once attempts to sort things out have failed. You can, ultimately, get your partner to ask if you can swap to a different midwife. ‘My midwife was a harridan,’ says Katherine, mother of Millie (1) and about to give birth to her second baby. ‘I found out later that she was famous for it. She bullied me, pushed me around – quite literally – and said many unhelpful things. I feel she made the birth unnecessarily scary. This time I’m going to ask for a different one if I get her: no question. I feel much more confident about doing so as a second time mum. I wish I’d known I could ask for someone else first time round.’

AN UNFAMILIAR PAIR OF HANDS | Most women, after they’ve given birth, use superlatives when talking about their midwives. I still have dreams featuring the wise, comforting figure of Penny who attended Ted’s birth. But if you are worried about being attended by a stranger during childbirth talk this over with your midwife beforehand. Choosing to have another woman (friend, relative or doula) with you during labour means you – and your partner – will be with someone you trust, even if you won’t know your midwife.

You can also call the Head of Midwifery at your hospital and discuss your worries with her. It’s not unheard of (resources providing) to be allotted a smaller ‘team’ of midwives, who you can get to know, and one of whom will do their utmost to attend the birth. Midwives want to help you give birth in the way that’s best for you. They can be surprisingly flexible. But be realistic: these are overworked women fighting staffing shortages and they can’t work miracles.

And incidentally, your midwife may be a ‘he’. At the end of 2002 there were 93 male midwives in the UK.

INDEPENDENT MIDWIVES | If your concern about not knowing your midwife is acute, if talking to the hospital was fruitless and if you have the readies, this is certainly an option. An independent midwife is not cheap (they can cost somewhere in the region of £2000). They are basically freelancers, fully trained by the Nursing Midwifery Council, as are all NHS midwives. Many have opted out of the NHS simply because they want more human interaction and continuity from their jobs. They can be fantastically supportive and committed. Some will do hospital births – they may have a contract that allows them to attend you in your local hospital. Many, however, restrict themselves to homebirths (but will stay with you if you have to be transferred to hospital). If you hire an independent midwife she should see you throughout pregnancy for all your antenatal checks and be there for the birth. It’s worth knowing, though, that independent midwives may not be insured (because of the high cost of insurance). You should consider this when weighing up whether to hire one.

Where to go for help:

Independent Midwives Association, 1 The Great Quarry, Guildford, Surrey GUI 3XN 01483–821104 Email: information@independentmidwives.org.uk www.independentmidwives.org.uk

There are many things about birth that may seem like hitches or horrors, but are actually a series of choices for you to make if you know how. Here are some common labour challenges and what to do about them.

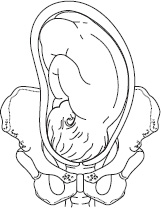

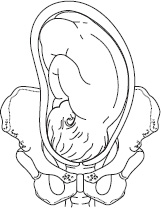

A baby that isn’t lying right is one of labour’s biggest challenges. A vast proportion of difficult labours (particularly first time) happen because the position of the baby’s head makes it hard for him to move smoothly down through your pelvis. This slows labour down and can make it more painful. This is one of the most common reasons why women have a caesarean first time around. Sometimes, when you are in the last stages of pregnancy, a midwife may be able to feel your baby’s position (with her hands, and by locating your baby’s heart beat). If your baby is not in the ideal position, there may be things you can do to change the way he’s lying: spending time on hands and knees is one approach commonly suggested to mothers-to-be. There is, however, some debate in the medical community about whether these approaches really work or not. Still, if something might possibly help your baby to get into the ideal position for this birth, and it’s not painful or unsafe to try, then it’s surely worth a shot.

Left occipito anterior The most usual way for a baby to lie, i.e. facing more towards your spine, with the narrowest part of his head pressing on your cervix.

Right occipito posterior The baby is lying in a ‘posterior’ position, i.e. facing upwards. Can cause problems in labour.

GOOD POSITIONING IN A NUTSHELL

During pregnancy, particularly the later stages:

Where to go for help:

Sit up and take notice: Positioning Yourself for a Better Birth by Pauline Scott (National Childbirth Trust, 2003). Available from NCT maternity sales 0870 112 1120 www.nctms.co.uk

A baby is breech when instead of being head down, her bottom, foot or feet – instead of her head – want to be born first. About three to four per cent of babies are breech at the end of the pregnancy. Finding out your baby is breech is the sort of hitch that plunges many pregnant women into a panic. But it’s important to stay open minded about your baby’s bottom. Throughout most of your pregnancy it’s fine for her to be hanging around facing any way she fancies. But by about 36 or 37 weeks she probably should be thinking about turning head down. Some babies stay breech until the last minute – some even turn during labour – but you may not want to leave it this long. In 2003, researchers concluded6 that having a planned caesarean rather than a planned vaginal birth reduces the chances of your baby dying or becoming seriously ill during or after the birth if she is breech. However, several options for attempting to turn a breech baby (see below) are worth trying before you schedule surgery.

BREECH TILT | This is something many doulas would suggest. It’s harmless and some women say it worked for them.

LURING THE BABY | Penny Simkin, in her book Pregnancy, Childbirth and the Newborn (see further reading), suggests something that may seem wacky in cold blood. You shine a light up your vagina several times a day, hold a radio playing softly at your vaginal opening/pubic bone or get the baby’s father to talk to the baby from there. As Simkin puts it: ‘We know that the fetus can hear very well and responds to sound coming from outside the womb. We think that if the fetus hears pleasing sounds coming from low in the uterus, he might move his head down to hear it better. While not always successful, numerous women who have tried this technique have reported that their babies turned.’7 There’s a certain logic to this and, again, it won’t hurt to try.

ACUPUNCTURE | A technique called Moxibustion has been used for centuries in China to turn breech babies. Limited trials in the West have also shown it may work, but there’s no conclusive clinical evidence. Many women also believe acupressure (there’s a point on your little toe called ‘Bladder 67’) helped turn their baby. Talk to your midwife before you go to an acupuncturist. Try the British Acupuncture Council, 63 Jeddo Road, London W12 9HQ 020 8735 0400 www.acupuncture.org.uk

EXTERNAL CEPHALIC VERSION (ECV) | A lot of research has been carried out to show how safe this technique is and it has excellent success rates. All hospitals should now offer this to you, at around 37–38 weeks, and if yours doesn’t you can ask to go to one that does. You may be given a drug to help relax the muscles of your womb. The doctor will work out your baby’s position using an ultrasound. She’ll then press on your abdomen to turn the baby into the head down position. If the baby shows signs of distress she’ll stop. Sometimes ECV works completely, sometimes it works but the baby turns back later and sometimes it doesn’t work at all. ECV is more likely to be successful if:

ECV can be pretty uncomfortable (this isn’t a euphemism – it shouldn’t be actively ‘painful’). Women have described it as ‘a huge rummage’, and this, for most of us, can be hard to handle (mentally as much as anything else), so use your relaxation techniques and take someone for moral support. It’s pretty counterintuitive to have anyone pushing at your abdomen when you’re heavily pregnant and it’s easy to tense up. But remember that this is a common, safe procedure and it may well work.

If your baby does stay firmly breech this does not mean the birth is now out of your hands. It is perfectly legitimate to discuss vaginal breech birth with your obstetrician and to get a second opinion if you want. You will feel much better about having a caesarean if you are completely convinced of the reasons why it is advisable. If you choose a caesarean don’t give up on your preparations for this birth: you can make the surgery FEEL like a birth rather than a scary op, by reading Chapter 6: Surgical Birth.

Where to go for help:

Breech Birth: A Guide to Breech Pregnancy and Birth by Benna Waites (Free Association Books, UK, 2003) A comprehensive book, written by the mother of a breech baby, addresses the whole experience of breech from causes to turning techniques to the options for birth.

If your baby is hanging around past her due date, you’re not alone: only 58 per cent of women have actually produced a baby by the time they are 40 weeks pregnant8. Around 20 per cent of us end up having our babies induced by doctors or midwives (see below for methods)9. If you don’t go into labour within 10–14 days of your due date, your hospital will probably offer to put you out of your misery by inducing the baby. They may present this as a fait accompli, but, like all else, it is a choice you can make by weighing up the pros and cons. The usual concern is that if a pregnancy goes on too long, your placenta may begin to work less effectively, putting your baby at risk. Studies show that the risk of stillbirth increases from 1 in 3000 for women who are 37 weeks pregnant, to 6 in 3000 for women who are 43 weeks pregnant10.

That’s not to say ALL overdue babies are ‘at risk’. Some hospitals have a policy of inducing all babies when they are ten days overdue, some at two weeks. If your midwife or obstetrician mentions induction, consider this an opening gambit. Discuss the pros and cons. If your baby is more than two weeks overdue and you still do not want to induce, doctors and midwives should monitor you closely (usually this involves the baby being monitored in hospital every other day). Having said this, most women, by 42 weeks, are begging the doctors to get labour started.

On the begging front – here’s a note of caution: in the US (and it’s not unknown in the UK) there’s a trend towards women scheduling inductions for convenience. They’re sick of being pregnant, they want to time the birthday to a certain date and so on. It is worth knowing, if you’re tempted by this, that while induction can be a blessed relief, it isn’t necessarily much fun. Studies show it is likely to result in more medical interventions (e.g. ventouse, forceps and caesarean) and many women describe their induced labour as more painful than their ‘natural’ one. Of course, if your baby has to come out (but doesn’t seem keen to) you may not have the option of turning down induction. Don’t give up on the birth though. There are tons of things you can do to ensure a safe and positive experience of induced labour.

SEX | It may be a grim thought at this elephantine stage but having sex is an excellent way to induce an overdue baby. Sperm contains prostaglandin, the hormone that softens the neck of the womb (which will help it to open). If you can orgasm, your body will also release some oxytocin (responsible for womb contractions too). If you’re not, perchance, feeling like a sex goddess just grit your teeth and think of England. And do this as often as you (and your partner) can bear to (well, at least a couple of times anyway) in a 24-hour period. Don’t expect to go into crashing labour immediately one single act is over. It might be a few hours before anything begins to happen. And it might not work at all.

SOME OTHER NATURAL WAYS YOU COULD TRY

A word of caution. Always make sure your midwife apporoves whatever you’re trying. If your baby isn’t ready nothing will happen. But if he just needs a little prod things can go fast.

This shouldn’t really be a singular noun. Medical induction can mean many things, ranging from the midwife breaking your waters (‘artificial rupture of membranes’ or ARM) to getting hooked up to a drip of synthetic hormones for the duration of labour. Each of these methods has pros and cons so discuss all the angles with your midwife/doctor before you agree to anything. It’s also best to see induction as a possible series of events rather than a fixed date at which you’ll have your baby.

CERVICAL SWEEP | This can be done from around 40 weeks. The midwife puts a finger into your cervix and swirls it around the edge. You get to go home after this and it may take 24–48 hours to work. Good because: it’s minor and you can then labour without intervention if it works. Studies show that it prevents one in six inductions. Drawbacks: like any internal exam, it can be uncomfortable. How to cope: Talk to your midwife about what to expect and tell her if you are nervous. Ask her to explain what she’s doing as she’s doing it. Agree with her that you can say ‘stop’ at any point. Help yourself by lying with your hands under your bum, as this will bring your cervix forward. Focus on staying calm and relaxed using slow breathing, and have your partner with you. Try visualisations to distract yourself and remember it’s a quick procedure.

PROSTAGLANDIN GEL | This is sometimes – though not always – used along with a cervical sweep. Prostaglandin is a hormone that gets labour started. The midwife will put a pessary or gel up your vagina so that it’s next to your cervix. You’ll stay in hospital from now on. Your baby will usually be monitored with an electronic fetal monitor before and after the pessary goes in. You’ll probably then be asked to rest in bed (at the hospital) for an hour then get up and walk around but you won’t be allowed to go home after this. After six hours, if nothing has happened, you can have another pessary. Three pessaries are usually the most you’ll be offered. Good because: it involves little intervention, does not hurt and may not involve any further interventions Drawbacks: might not work or it might stimulate your womb to contract too frequently (‘hyperstimulation’) which can distress the baby.

BREAKING YOUR WATERS (‘ARTIFICIAL RUPTURE OF MEMBRANES’ [ARM]) | The medical words sound scary (anything with ‘rupture’ in the title, at this point, can seem unpalatable). But ARM should not be hard to handle. The midwife breaks the bag of waters surrounding your baby by hooking and puncturing them through your cervix (they don’t have nerves in them so this should not be any less fabulous than a basic internal exam). After ARM you’ll be advised to walk around for a few hours, before being checked again. Often ARM is used after prostaglandin. Sometimes you’ll be offered ARM if your labour stalls part of the way through. There are other options to get a stalled labour going again, though, see page below. Good because: it isn’t particularly painful and may not involve any further interventions. Drawbacks: once your waters are broken most hospitals will have a policy that the baby needs to be out within 24 hours to avoid ‘infection’. This is a ‘no going back’ step.

Julia has seen women lose all sense of control because of an induction: ‘Raiza was an assertive woman who wanted natural childbirth. We worked for the weeks before her birth on positions for comfort and natural methods for moving the baby along. The baby was very overdue and Raiza agreed to have a syntocinon drip to get things moving. She then became a woman I didn’t know. She lay passively, allowing the attending doctors to speak over her to her partner about her progress. She took the induction as defeat and not as a choice she herself had researched and approved. She had little joy in the vaginal delivery of her little girl and told me later that no matter how many times I’d told her to expect the unexpected, she thought it wouldn’t apply to her. A thoughtful acceptance of medical interventions, or a quick choice due to medical necessity should never be seen as defeat. You are still giving birth, and many elements of your birth plan (see Chapter 7) can remain, if you keep making those choices as you go.’

Aromatherapy can help induction,’ says Penny Green, an Oxford midwife. ‘Clary sage, rose, jasmine or lavender can be used before any medical intervention or an hour after ARM to get things going.’

SYNTOCINON DRIP | Syntocinon is the artificial form of oxytocin, the hormone your body gives off to start labour. This is the most major induction step. The doctor prescribes syntocinon and the midwife gives it to you, following a strict protocol as to the rate/speed of the drip (the drip starts slowly and is gradually increased so that your womb is not over-stimulated which would distress the baby). You’ll usually be in bed for this, hooked up to a drip and your baby will be monitored using an electronic fetal monitor (a band around your waist attached to a machine by wires). This kind of induction can make contractions come hard and fast. Sometimes a ‘whiff’ of syntocinon can start your labour off brilliantly, and you will be able to come off the drip and labour on your own. Some people react quicker to syntocinon than others because of the stage of labour they are in, or their readiness to labour if they are being induced. However, particularly if this is your first baby, you may need to be hooked up to the syntocinon throughout labour. You are more likely, if this is the case, to want an epidural (be realistic about this possibility – syntocinon really can make labour harder). Good because: it really will get labour going once and for all. Drawbacks: contractions can be more painful, and it raises your chances of having other interventions such as epidural, ventouse, forceps or caesarean.

Don’t panic: this procedure might just kick things off for you.

Discuss all risks and benefits in advance. Understanding it properly will help you cope if it’s tough.

If at all possible, opt for a mobile epidural: this way you can still walk and pee with your syntocinon IV tagging along (see epidurals, below,). Your birth partner can manoeuvre the IV pole and tubing so you won’t notice it. You can stay mobile, and use gravity to minimise the chances of further interventions. (Even sitting upright in a chair is better than lying flat on your back.)

Where to go for help:

When Your Baby is Overdue, a MIDIRS ‘informed choice’ leaflet is good for presenting all the issues (see Find Out More). Download it free from www.infochoice.org.

There’s a baby in there and it’s got to come out – you’ve no choice about that. But you have many options when it comes to the details. I remember when I was pregnant the first time, a mother of three in my yoga class advised me to ‘read up on everything to do with birth’. This was somehow meaningless to me. I had no idea where to start or what to read. Apart from handling pain, I didn’t know what I should be concerned about. So I read one (very medical and thorough) popular childbirth book. I went into that birth in a quivering state of ignorance that did me no favours when the going got tough and I had to make decisions. Many women have this experience first time, and vow never to be like that again.

CHOOSE TO MOVE | It’s simple: you should move around and, as much as possible, stay upright during labour. If you think you might forget this, have it tattooed in fluorescent foot high letters on your belly right now. Don’t rely on the medical staff to remind you about positions during labour. The National Childbirth Trust (NCT) says that up to 40 per cent of us are currently not advised to stay upright and move around during labour and instead lie on our backs, even though research shows that upright positions and movement can be very beneficial. In other words, it’s up to you – and your birth partner.

Midwife Jenny Smith is unequivocal on this one:

‘It is always best to be in an upright position rather than lying on beds. The best way to encourage your womb to work in the most proficient way is for you always to adopt a sitting, standing or kneeling position during labour. This will maximise the opening of your cervix and help your baby to descend through your birth canal. It will also ensure that the blood flow from you to your baby is good. If you lie on your back during labour, you may compress a large vein called the vena cava. This can impede the blood flow to your baby, which can reduce the oxygen available to him and then cause “fetal distress”.’

You don’t, of course, HAVE to move if it doesn’t feel right. You can choose to stay very still if this is what your body is telling you to do. But if you do feel like lying down (as opposed to being told to lie down by someone else), don’t lie on your back for any length of time unless you have to (for instance, if you’re having an internal examination). Instead lie on your left side, as if you are asleep in bed, sit up against pillows, or lean over a birth ball (see for positions).

Where to go for help:

The Active Birth Centre is helpful on positions 020 7281 6760 www.activebirthcentre.com

The NCT also has good information on movement and positions for labour.

Try the NCT ‘Guide to labour’ available from NCT maternity sales 0870 112 1120 www.nctms.co.uk.

FETAL DISTRESS

What is it?

Mostly, ‘fetal distress’ is used to mean changes in the baby’s heart rate tracing. But the term is subjective, and there is no universal medical definition. This is why the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists now urges American doctors to say ‘non-reassuring fetal heart rate tracing’ instead of ‘fetal distress’.

What are some possible signs of fetal distress?

What do these signs mean for you and your baby?

Listening to your baby’s heart rate is the best way for the midwife or doctor to tell whether or not your baby is becoming ‘distressed’. This may be done using either one or all of the following:

HAND-HELD MONITOR | Hospitals have different policies and approaches to monitoring the baby’s heart rate. The most recent recommendations from the National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) say that if you’re healthy with a trouble-free pregnancy then about every 15 minutes (and about every five minutes towards the end of labour) the midwife should simply listen to your baby’s heart using a hand-held device. She should listen to your baby before, during and after a contraction to see how he copes with the squeeze of the contraction. According to NICE there should be no need for electronic monitoring unless there is genuine concern about how well your baby is coping. However, many hospitals will ask to hook you up to the EFM when you arrive, so that they can get an initial picture of how your baby is doing. This is your choice. If you decide you’d rather the midwife used a hand held device, you should say so (and put it in your birth plan).

ELECTRONIC FETAL MONITOR (EFM) | There are many reasons for the hospital wanting to monitor your baby using an electronic fetal monitor (EFM). These include certain pregnancy complications (such as diabetes or pre-eclampsia), a twin or multiple pregnancy, an induction or epidural and any concerns about your baby’s heart rate during labour. If you agree to an EFM, the midwife will attach a couple of elastic belts around your belly. One belt monitors the contraction, and on the other the sensors pick up the baby’s heart rate and transmit it to the electronic monitor which ‘traces’ the heartbeat on a print out (called a ‘trace’ or ‘CTG’).

EFM isn’t, however, necessarily your best choice if you have no complications. ‘You’d think continuously listening to the baby using an electronic monitor would be an excellent idea,’ says obstetrician Lucy Chappell. ‘But the benefits of EFM are not so straightforward. EFM was introduced with the aim of reducing deaths and cerebral palsy in babies. But it has not actually been shown by studies to improve these outcomes over hand-held monitoring in a low risk birth. In fact, there can actually be disadvantages to having EFM (such as more medical interventions) unless there are medical reasons to do so.’ One issue is that ‘interpreting the CTG is more imprecise than you would imagine. Human error – both in how the print out is interpreted and what happens next – can happen’. Occasionally doctors or midwives might not recognise a problem, might not act on the information they have in front of them or might act too soon, intervening unnecessarily.

It is, then, a really good idea to talk to your midwife before you are in labour about the pros and cons of EFM. This way you won’t have to make any stressed, sudden decisions and also you will fully understand any risks you are taking either way.

Once the monitor is on, remember that you do not have to become the ‘patient’.

You may have to be lying on a bed while the belt is being attached but there is no reason why you should be forced to lie on your back while the monitoring is actually going on. Although your range of movement will be limited by the wires which are attached to the machine, you can sit in a chair or on the bed, upright with pillows and the bed back up, or you can rock on your birth ball, stool or beanbag. Again, you might want to put this in your birth plan so you don’t have to quibble about it at the time. Even if you have a drip in your arm, you can do all of these things.

A few hospitals have mobile EFM devices – they work by ‘telemetry’ – and you can wander around happily while the monitoring is going on. There are even devices which work in water. You can at least ASK about these options before you are in labour: if they have these kinds of monitors – particularly if you know that you will be having EFM – you can plan to use them.

FETAL SCALP CLIP | Occasionally, if there are some concerns about your baby, the doctor may want to put an electrode on your baby’s head to pick up her heartbeat directly. This is a kind of clip, attached to your baby’s scalp (via your vagina) and connected to the monitor. If there’s real concern from this, they have to act. They may want to deliver your baby quickly (instrumentally or by caesarean), or they may decide to take a couple of drops of your baby’s blood from her scalp (‘fetal blood sampling’) to test the oxygen levels (to find out for sure whether she is ‘in distress’).

AND YOU! | ‘One of the very best monitors of your baby’s well being, during labour, is you – the mother,’ says midwife Jenny Smith. ‘If you feel the baby’s movements have stopped or slowed down, tell your midwife straight away. Your baby is probably just resting, but your instincts, and your relationship with the baby inside you, can tell us a lot about how your baby is coping during labour.’

Where to go for help:

The Active Birth Centre offers information on staying mobile in labour. 020 7281 6760 www.activebirthcentre.com

National Institute for Clinical Excellence: MidCity Place, 71 High Holborn, London WC1V 6NA 020 7067 5800

Further Reading:

Monitoring Your Baby’s Heartbeat in Labour: A Guide for Pregnant Women and Their Partners (National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2001) This is the official advice on fetal monitoring.

Full Clinical Guideline on the Use of Electronic Fetal Monitoring, published by the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists is more detailed. Both available from www.nice.org.uk

Listening to Your Baby’s Heartbeat During Labour (MIDIRS, 1996). A Midwives Information and Resource Service (MIDIRS) ‘informed choice’ leaflet (see Find Out More). Download it free from www.infochoice.org.

The vast majority of first time caesareans (not to mention other interventions) happen because of ‘failure to progress’. Basically, this is when your labour takes too long or stalls entirely. Usually this happens because the baby’s head is not in the best possible position for birth. To lower the chances of your labour stalling:

Where to go for help:

The Labour Progress Handbook: Early Interventions to Prevent and Treat Dystocia, Penny Simkin and Ruth Ancheta (Blackwell Science, UK, 2000) is quite technical, but a great resource for anyone concerned about failure to progress.

If your baby is head down, but facing upwards with his spine against yours (instead of his face towards your spine) this is called ‘back labour’ or a ‘posterior’ baby. This position can slow labour up, and make contractions ridiculously painful. But don’t give up all hope if this happens to you. Sometimes a baby will turn into a better position during labour. Some midwives say being on your hands and knees as much as you can in labour will encourage this. The methods below can all help to relieve the backache that usually comes with a back labour. Some are going to sound silly, but if you’ve had back labour once, you’ll try anything to help it the second time.

Water: a jet of water on the lower back works as ‘counter pressure’.

Tennis ball: counter-pressure again – your partner can roll a tennis ball on the sore bit during contractions. A cold coke can or a bottle of frozen water will also work.

Rice sock (see Chapter 9, page, for what it is and how to make one): put it on your lower back or on top of your pelvis.

Double hip squeeze: again, counter pressure focusing on the hip area. Your partner presses one hand on each of your hips during the contraction, pushing them gently but firmly together.

Rolling pressure: the cold can or bottle or even a rolling pin.

Cold pack/hot pack on your lower back: again, if it feels right, then do it.

Hands and knees: just getting onto hands and knees and staying there for a while helps to get the baby off your back for a breather. It may even encourage the baby to turn a bit.

Group B streptococcus (GBS) is a common type of bacterium carried by about a third of women. It can come and go which makes screening controversial and possibly not as helpful as it might be. You wouldn’t know it’s there and it doesn’t do you any harm, but it is the most common cause of bacterial infection in newborn babies in the UK (though it’s still rare: about 1 in 1000 babies develop GBS – that’s only about 700 babies in the UK a year). It can make a baby get very sick, or even die, which is why some hospitals are now screening women during pregnancy for GBS. If you are found to be GBS positive you will be advised to have intravenous antibiotics when you go into labour. These should be given at least four hours before the baby actually comes out, and involve being connected to an IV tube and pole for 15–20 minutes every four hours.

Again, probably the biggest challenge here is how to avoid suddenly feeling like a patient (having an IV in your arm can make you feel like something out of ER if you’ve not thought it through first).

Discuss your plans to move freely/use water with the midwife: there is no technical reason why you can’t be in a tub with an IV in your arm providing you keep the arm out of the water, but your midwife may take a little persuading.

Get your birth partner to take charge of the IV: moving the pole if you want to move, keeping you from having to think about it at all.

Remember that you are still healthy and strong and more than capable of giving birth: the IV is nothing but a safeguard.

Where to go for help:

Group B Strep Support, po Box 203, Haywards Heath, West Sussex RH16 1GF. They have an excellent leaflet called GBS and Pregnancy: preventing GBS infection in babies. Helpline 01444 416176 or online www.gbss.org.uk

An instrumental birth is where the baby needs to be ‘helped’ out, in the final pushing stages, by a suction device called a ventouse or by tong-like instruments called forceps. This might happen if the doctors judge that your baby needs to be delivered quickly (if, for instance, your baby is in distress or you are exhausted and have been pushing for a very long time with no progress). A ventouse looks a bit like a small hat with a tube coming out of it. The doctor puts this on the top of your baby’s head to pull as you push. Sometimes, after ventouse, your baby’s head might be temporarily (and harmlessly) ‘cone’ shaped, or have a red mark where the suction was put on. Forceps look like a large pair of spoons. The doctor puts them round the baby’s head to pull as you push. Again, sometimes your baby’s head might be marked or bruised by this – but not permanently. Ventouse is more commonly done in British hospitals as it is considered gentler and you do not usually need an episiotomy (a surgical cut to your perineum that is stitched after the birth under local anaesthetic). But forceps often involve an episiotomy.

YOUR CHANCES OF INSTRUMENTAL BIRTH

If you think all this won’t apply to you here are the facts:

If you are making the right decisions – before and after the birth – you really are going to reduce your chances of having an instrumental birth. But you won’t eliminate them entirely. This sort of thing may sound unpalatable but there are many ways to cope if your baby needs a bit of help to emerge. Instrumental births can be a huge relief from an exhausting pushing stage. But if you’re totally unprepared, they can also be upsetting. Julia has seen women really distressed by the use of ventouse or forceps, largely because they took the ‘never thought it would happen to me’ stance (so tempting, for all of us). It’s a good idea, then, to look instrumental delivery in the eye now, so that if you end up staring down the barrel of a suction cap, you will cope fabulously. This is particularly true for first-time mothers: you are more likely to have an instrumental delivery first time around, than if you have had a vaginal birth before.

One of Julia’s clients, Topanga, 29, mother of Sean (2) describes her forceps delivery like this:

‘The forceps looked like salad tongs or farm equipment. I had been pushing for quite a while and my midwife explained how and why they were needed. I had an epidural and also a local anesthetic in my perineum, so I really didn’t feel anything at the time. The metal sticks looked scary. But, oddly, I was fine. I felt pressure on my back as Sean was born, but at the time it was only odd, not painful. I couldn’t have really prepared my body for the forceps, but I did speak with my midwife before Sean’s birth about instrumental births, so mentally I sort of knew what was coming. Sean was fine, but had three small bruises over and around his eye. He was watched for jaundice and his head looked a little pointy for a bit, but within 24 hours he was fine. My recovery was harder, I was sore, couldn’t really sit up and in hindsight, I should have taken every pain reliever they gave me. Everyone around me acted like I should be elated to have had a vaginal birth, not understanding the special recovery I needed.’

HOW TO LOOK INSTRUMENTAL BIRTH IN THE EYE | Talk to your midwife about instrumental delivery before you are in labour (and don’t be brushed off with ‘oh, that won’t happen to you’ type of response).

Ask her:

If you’ve done this, then should you have an instrumental delivery, you will know the answers to these questions and will be able to hunker down and deal with the process, accepting that you’ve done everything you can to avoid it. (See ‘Ways to cope’ below.) Finally, as with every other aspect of birth, don’t be tempted to see instrumental birth as some kind of failure. If you have prepared, made active decisions and feel genuinely informed and consulted about these procedures they can be totally manageable (even a blessed relief: they’ll get that baby out once and for all, and labour will be OVER).

‘You can make a huge difference by making these the best pushes of the whole labour: really give it your all. This way the obstetrician has to use less effort, which is much better for you and your baby.’ Obstetrician Lucy Chappell

When I had Izzie, my first baby, I was convinced that only drugs would really work when it came to ‘proper’ labour pain. I had an epidural followed by various interventions. Second time around, I gave birth in hospital with no medication, and third time around, I had Ted on the living-room floor using gas and air. There is no ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ way to handle pain of childbirth. But there are mistakes you can make if you’re ill-informed. I made a classic with Izzie: I had an epidural because I was scared that it might GET too painful – not because it actually WAS so at the time (though it was no picnic). If I’d had a clue about alternative ways to relieve the pain, I wouldn’t have considered the epidural at that early stage. I had no idea that an epidural might lead to more interventions (such as the syntocinon drip I was then given to keep labour going). I just thought it would stop the birth from hurting. If you’d asked me back then whether I thought things like massage, relaxation, positions, movement or water could really work against labour pain I’d have laughed. Now I’ve actually used these methods all the way through, I honestly believe that as long as the birth is going smoothly (and this is a big caveat), these woolly-sounding methods of pain relief work wonders.

The large US survey Listening to Mothers11 highlighted how little women actually use alternative (i.e. not pharmacological) methods of pain relief, but how highly we rate them when we do. If you want to avoid medical intervention where possible, the trick is to try everything – properly – before you dismiss it as hippy nonsense. Our capacity for guilt and self-blame when it comes to childbirth is apparently boundless. If you’ve tried lots of ways to cope with the pain, and you fully understand the pros and cons of each choice you make, then you’re more likely to be reconciled to events.

Jenny Smith says, ‘It’s vital to practise these natural methods of pain relief (with your partner) BEFORE you go into labour, so you know how to do them – so they’re second nature to you both – when you need them.’ You may, of course, feel absurd squatting in your loved one’s arms breathing deeply while pretending to give birth but it’s worth doing.

A WORD ABOUT THE PAIN RELIEF POLICE | There’s a certain tyranny out there about pain relief – a knot of fervent birthers who’ll give you the impression that it’s somehow morally BAD to have an epidural or that you’re a failure or ‘not woman enough’ if you turn to the anaesthetist. This is claptrap. Childbirth hurts. If it’s hurting too much and nothing is working, you should surely not be suffering traumatic pain if you can do something about it.

No two labours are alike, and no woman can tell another what she should, and shouldn’t do about hers. There is, however, certainly an argument that we’re so woefully unprepared for handling the pain of normal childbirth that we panic when it hurts and think that drugs are the only option. Drugs are AN option. And thank the Lord they are. But they’re not without their drawbacks, and they’re certainly not your ONLY option. The best place to start, as always, is with the least risky approach to pain relief, working your way up a scale that runs from yogic chanting to general anaesthesia. This way, if someone suggests you are selfish, weak or ill-informed for having an epidural you can deck them there and then, with a clear conscience.

A WORD ABOUT TENS MACHINES | The ‘transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation’ machine (you can hire one from Boots 0845 070 8090) fixes onto your back with sticky pads, and sends electrical pulses which stimulate the release of your body’s natural painkillers (endorphins). This has no effect on the baby. It’s most likely to help if you’re having a long, slow early labour. Some women say it doesn’t work well enough to make a difference, others say it was great – an early labour lifesaver. Studies into whether TENS really works have been inconclusive.

The most commonly used pain relieving injection for women in labour is pethidine. Pethidine is an opioid, a bit like morphine, and it sedates you (basically, so you care less about the pain). You may even go to sleep. It does, however, have well-documented adverse effects on babies. It crosses into the baby’s bloodstream and can make a baby sleepy and slow to feed, which can be a genuine problem in the first few days. It can also give the baby breathing problems. A fair number of women say they hated pethidine – it made them throw up and feel sleepy and disorientated. Others say that feeling ‘out of it’ helped them through the long, painful early stage. One study in 199612 concluded that labour pain is not sensitive to injected morphine or pethidine and that the drugs only cause heavy sedation so shouldn’t really be offered as pain relief to women in labour. You may, then, want to think about other forms of pain management (TENS, positions, breathing etc.) instead of pethidine.

N.B. Some hospitals use ‘meptid’ for this kind of injected analgesia because there is a lower incidence of respiratory problems in newborns. But this drug can also make you sick, sleepy and spaced out, as above.

This is a mixture of nitrous oxide and oxygen, inhaled through a mask or mouthpiece to take the edge off the pain. Many women find this a fantastic source of pain relief and some use only gas and air in labour. Rarely, it can make you a bit hysterical. But then again, so can childbirth. You can use it at any stage of labour, with any other form of pain relief. I had gas and air in the final stages of Ted’s birth and though I don’t think it made many inroads on the pain, the ritual of grabbing that mouthpiece and breathing deeply when it really hurt was amazingly helpful. There are no known adverse effects on you or the baby.

You’ve probably met women who grip your arm and hiss ‘get an epidural’ the minute they hear you’re pregnant. This is understandable. Epidurals can be fantastic. But they are also linked to other – less fantastic – interventions. And you may not be able to get one the minute you want one. Understand the issues, here, and you will make real choices about pain relief, not pretend ones.

About a quarter of us will have an epidural. This can be genuine blessing – if the pain really becomes unmanageable, or if medical interventions are needed, or if your labour is long and arduous and you are exhausted. But an epidural is not without some drawbacks.

A recent study13 examined eleven trials involving over 3,000 women and found that while epidurals provide better pain relief than non-epidural methods, they are associated with: longer first and second stages of labour, an increased incidence of fetal malposition (when the baby’s head is not in the best position for birth) and an increased use of oxytocin (a drip to speed up or strengthen labour, which can lead to fetal distress which in turn can lead to other interventions to deliver the baby, including caesarean). An instrumental vaginal delivery (see above) is nearly twice as likely with an epidural. Of course, there is a bit of ‘chicken and egg’ going on here: it is hard to distinguish in studies whether the epidural itself actually caused these interventions or whether the labour itself was becoming complicated and therefore led to the need for stronger pain relief (and interventions to get the baby out). All doctors can really say for sure is that there is a ‘link’. Studies have shown, incidentally, that having an epidural does not directly affect your chances of having a caesarean. Finally, women who have an epidural tend to report lower satisfaction levels with the birth, despite saying they had good pain relief.

CONVENTIONAL EPIDURALS | The anaesthetist injects local anaesthetic (bupivacaine) through a tube that has been inserted into your lower spine. This completely removes all sensation from the lower part of your body: you are immobilised, and, once the anaesthetic takes hold – usually this takes about 15 minutes – you should feel no pain at all. The tube is left in your spine so that the anaesthetic can be ‘topped up’ (about every 90 minutes) by the midwife. Often, the midwife will allow the epidural to wear off when you reach the pushing stage, because this can help you push more effectively. For some women, this means being catapulted into pain again (how much pain will depend on how much of the epidural is allowed to wear off). You might want to discuss – before you go into labour – the advantages and disadvantages with your midwife of letting the epidural wear off for pushing. ‘There is a fine balance when it comes to the pushing stage,’ says Jenny Smith. ‘You certainly do not want the mother to feel acute pain but you do want her to feel pressure so that she can work out how to push effectively.’

N.B. Some hospitals use a ‘combined spinal’ epidural, where the anaesthetist injects the anaesthetic directly into your spinal fluid. The resulting pain relief is the same, but it works more quickly (in about five minutes). You might be given this kind of epidural if you need one quickly (for instance, if you are going to have an emergency caesarean).

MOBILE EPIDURALS | Nowadays, most (though not all) hospitals offer ‘mobile epidurals’. These combine a local anaesthetic with another pain-relieving drug called fentanyl. The addition of fentanyl means that you can have a lower dose of the numbing local anaesthetic. This ‘low dose mixture’ keeps you pain-free, but lets you move around much more than a conventional epidural. A mobile epidural can either be administered the same way as a conventional epidural, but using low dose mixture (this should take about 20 minutes to work), or it can be administered using a ‘combined spinal epidural’, where the anaesthetist injects the anaesthetic directly into your spinal fluid and at the same time puts in an epidural tube so you can have future top ups. This technique works in about five minutes and might be used if you need pain relief very quickly.

A mobile epidural lets you feel your legs, walk about, and feel the urge to push (all without pain if the epidural is not allowed to wear off). You may feel a tightening in your abdomen with each contraction, but it shouldn’t hurt. The best thing about a mobile epidural is just what it says – you’re mobile. You can therefore move, use gravity and positions that may keep labour progressing, and help you push the baby out more effectively. If you have a conventional epidural, you can’t, for instance, squat to push, thereby using gravity in your favour. Having said this, if you need very frequent top ups of the mobile epidural to manage your pain, you may not be able to walk around, but you can still stay upright in a chair or on a birth stool for the pushing stage. Studies have found that having a mobile epidural means you are less likely to have an instrumental birth than you would if you had a conventional one. One major study14 concluded that: ‘The proven efficacy of mobile epidurals and their beneficial impact on delivery mode make them the preferred techniques for epidural pain relief in labor.’ Finally, if you have a mobile epidural you’re more likely to feel in control, and less likely to feel like a ‘patient’: which is certainly going to help you to feel as if you are coping well with the birth. There are no special medical indications for whether you should have a mobile or a conventional epidural: the only question is, which kind does your hospital offer?

There are some other advantages for choosing a mobile epidural over a conventional one. With a conventional epidural you may need a urinary catheter, but with a mobile one you may be able to pee unaided (if you have a long labour with lots of top ups this might not be possible). With a conventional epidural, your baby’s heart rate will be monitored continuously, using an EFM (see above page for the pros and cons of this), but with a mobile one, you might only need to be monitored using an EFM intermittently. Again, this may reduce your chances of having further medical interventions.

SIDE-EFFECTS OF ALL EPIDURALS

Most women find their epidurals helpful, sometimes immensely so. But they may not always be quite as straightforward as you’d expect.

Julia experienced the simple good side of a conventional epidural with her first birth: ‘I laboured for days and sobbed when the anaesthetist walked in. My midwife put her face to mine and said calmly: “Let it go.” I ate, dozed and waited for Keaton to be born. I had no side-effects of the epidural and it was a very positive experience, completely blocking the pain.’

Lissa, 35, mother of Phoebe (3) and Esme (1) had a mobile epidural with Phoebe: ‘The pain, which was horrific even though I was only at 4cm, just stopped. I could barely feel the contractions after that – just a faint tightening round my belly – and I could walk around normally. I even had a sleep, which was weird. I remember thinking “I’m supposed to be in labour, and I’ve just been asleep”. When they let it wear off, for pushing, though, it was really tough: I was catapulted from nothing, into horrible pain and I pushed for two hours. This was a big shock.’

On rare occasions, an epidural may go a bit wrong:

‘I had two epidurals,’ says Michelle, 30, mother of Joey (7) and Justin (4). ‘The first one “missed” and I just felt a cold tingle. The second one took but I felt “shocky” and cold. I developed a whopper of a headache immediately. I was crying, shivering and eventually my blood pressure crashed. It was a nightmare. Everyone acts like the epidural is just what you do, but for me, it was the worst possible choice.’

Epidurals may not, then, be a simple matter of getting a needle in your spine and settling down with Hello! until the baby comes out. Perhaps the most important thing to remember, however, is that even if you decide you will ‘definitely’ have one, you will still need all the pain-relief methods you can learn because epidurals are not instant. If you go into labour spontaneously, you’ve got to get to the hospital and, once there, it can take a couple of hours for an anaesthetist to get to you. You need some coping mechanism while this is happening. You may also have a labour that is zipping along so fast that there is no time for an epidural.

An epidural may be your salvation. But don’t rely on it alone to get you through the pain of giving birth.

Don’t get hung up on the small print here – they’re just ideas. The basic rule is MOVE and STAY UPRIGHT. If nothing else, make this your mantra.

These techniques should be a vital part of your pain relief armory. We cover them in Chapter 3: Fear and Pain. I’d say – and this still sounds as improbable to me as it may to you – that breathing and relaxation above anything else are what got me through the pain of Sam and Ted’s births. Go back to Chapter 3, page and practise these like a swotty schoolgirl hell bent on an A grade. They may not work for you, or work only for a while, but they’re certainly worth knowing about.

If your birth will be in a hospital make sure you understand exactly what they will allow you to ingest and why. In the UK fewer than 5 per cent of hospitals have a policy of letting you eat and drink whatever you want in labour, because of fears of complications should you need general anaesthesia (which are rare). The evidence of this is controversial. And surveys have found that it goes against our instincts.15 Graze – little and often – throughout labour if you feel like it. If you can’t, prepare other ways to fuel yourself: take sports/energy drinks, wholemeal crackers if allowed, and fruit juice. If you go into labour slowly, at home, try eating light but slow-burning food (see below). This kind of food will give you sustained energy for the hours ahead.

Avoid sugary food or food made with refined white flour that will give you an energy rush, then a crash when you need it least. If you choose wholegrain foods they’ll sustain you for longer. Things like wholemeal toast and marmite or if you feel like a meal, something like wholemeal pasta or a brown rice salad. But don’t eat large meals (you might just throw up – your stomach does not have room for lots of food while those big contractions are going on).