Strength Through Joy

(Kraft Durch Freude)

PREAMBLE

Not only did the Nazis seek to strengthen their hold over Germany through the vast propaganda machine embodied in events like the Nuremberg Rallies but they also used the power of the state to provide a whole range of material improvements to everyday life. It was a variety of ‘carrot and stick’ approach – propaganda and terror (more of that later) but also, as the regime saw it, improving the life of its citizens. This, of course, also boosted the economy and embedded the regime in popular affection.

Much of this was delivered by the vast KdF (Kraft durch Freude) or “Strength through Joy” organisation, part of the German Labour Front. It organised sporting and leisure activities in the workplace and elsewhere as well as holidays including cruises. It was said to be the world’s largest tourism operator in the 1930s and its most ambitious project was a holiday camp on the Baltic coast – thought to be the world’s biggest.

Construction of what was said to be the biggest holiday complex in the world on the Baltic coast, the Prora-Rügen KdF (Strength through Joy) complex, 1937 (Bundesarchiv, unknown)

In addition, the Nazi regime also built many other structures designed to demonstrate that National Socialism was creating a modern, consumer society which would become the envy of the world. The Nazis didn’t invent the idea of the motorway but they adopted it and developed it at a furious pace once they were in power.

Another aspect was the provision of spaces for Nazi-approved culture. Amongst locations of this type were the ‘Haus der Deutschen Kunst’, the House of German Art, an art gallery in Munich designed to show off ‘pure German art’. They also constructed a series of outdoor amphitheatres or ‘Thingstätten’ across Germany as auditoria for concerts, plays and other cultural events.

Alongside these Nazi expressions of public and communal nation-building, the regime leaders were also quick off the mark to ensure that they were able to relish life’s comforts. They soon enjoyed an opulent standard of living and built, or in some cases appropriated, grand private dwellings – many of them in the Bavarian mountains.

The post-war fate of these groups of buildings, both public and private, offers more evidence of the challenges faced by modern Germany in dealing with its Nazi heritage.

PRORA-RÜGEN KdF HOLIDAY COMPLEX, RÜGEN ISLAND, MECKLENBURG-WESTERN POMERANIA

The Nuremberg Rally Grounds are the most iconic surviving Nazi site and, arguably, the Prora-Rügen holiday complex on the Baltic coast is the most surreal. Its post-war fate also symbolizes the continuing debates about what to do with Third Reich buildings.

Prora-Rügen was conceived as a giant ‘Strength through Joy’ holiday camp which would provide seaside holidays for the German masses on the Baltic coastline. It was designed to accommodate 20,000 holidaymakers in eight huge buildings which extended almost 5km along the beach. The complex was designed following an architectural competition overseen by Albert Speer and, as well as the eight housing blocks, there were plans for swimming pools, theatres, cinemas and a festival hall which could have accommodated all 20,000 people staying there at one time.

Construction of the complex started in 1936 but was stopped on the outbreak of war in 1939. It was never completed and no one ever had a holiday there under the Nazis. During the war some Hamburg residents, escaping the Allied bombing of their city, took refuge in one of the blocks.

The remains of one of the blocks at the KdF Prora-Rügen complex dominate this part of the North German coastline (unknown)

Work on the Prora-Rügen holiday complex was never completed as it was abandoned on the outbreak of the war in 1939 (unknown)

The complex became part of the Soviet occupation zone after 1945 and some of the buildings were turned over to military use. A Soviet artillery brigade occupied one of the eight blocks. Many of the others were stripped of their useful materials and two of the eight blocks were demolished in the late 1940s.

After its handover to the East German authorities in the 1950s Prora remained a military facility. It was used by the National People’s Army of the GDR as a training area and public access was restricted. Part of the complex was also used as an army convalescent home.

Prora retained its military use after German reunification in 1990 with the army of the united Germany, the Bundeswehr, taking control of it and using it for a while as a technical school. There was much discussion in the 1990s about demolition of the blocks but instead they were given historic monument status. Thereafter, for the first time since 1945, there was some acknowledgement of the historical significance of the site. Controversy has continued to dog plans for its future.

Temporary exhibitions and then a more permanent museum, or Documentation Centre, about Prora KdF were established in one of the blocks. More recently a separate museum detailing the site’s role during the GDR era was also opened. On average around 80,000 visitors a year come to the Prora KdF museum which relies on entry charges to survive.

Promotional image of some of the new holiday apartments being created at Prora-Rügen (Standpark)

Of the six remaining blocks, one is in ruins. But four of the five surviving structures have been acquired by private investors who are at various stages of converting the blocks into holiday apartments, a hotel and other facilities. The fifth surviving block contains a new youth hostel opened in 2011 with 400 beds and funded by the local and federal governments. After seventy-five years something similar to the original purpose of the Prora complex is, thus, being realised.

Local opinion has been divided about these developments. For some it is a sensible use of buildings which are now legally protected and better being put to productive use than left to rot. Others regard them as irredeemably ugly, forever tainted by their Nazi provenance, and believe that they should be torn down. It is wrong, they argue, for money to be made by developers who, it is suggested, are realising Hitler’s three-quarters of a century old dream. There is, however, a suspicion that some of the opposition to the redevelopment has come from nearby holiday resorts worried about the competition that the luxury seaside accommodation will provide.

Prora-Rügen encapsulates many of the dilemmas surrounding the Nazi architectural legacy in modern Germany. On the one hand these outsized buildings are arguably seriously out of place and out of scale with their surroundings; even compared with the worst examples on Europe’s Mediterranean coastline they must rank as some of the ugliest holiday accommodation ever built. Their ugliness is, in part, an ugliness of association. Being the monumental product of an evil regime it can be very difficult to look at them other than as sinister.

It might also be difficult to imagine a complex of such scale being built in other countries in the 1930s but the style of architecture is not without parallel elsewhere. On the other hand like many other Nazi buildings, and apart from those specifically designed as places of terror, their purpose was not of itself sinister. It is this which has allowed many to see buildings like Prora in a very different light to concentration camps and even the Rally Grounds at Nuremberg.

Since work stopped on building the original Prora resort decisions about what to do with these vast edifices bequeathed from the Nazi period have been largely pragmatic. First, the buildings were put to military use and now, with the passage of time, there is a sense that their association with the Nazi era should not prevent them being regenerated even for their original purpose as a holiday destination.

As the redevelopment progresses it is by no means certain that the acknowledgement of the historical significance of the site will continue. The future of both Prora Museums is not guaranteed and currently the owner of the block where they are situated is allowing them to continue only on a year by year agreement.

No one ever had a holiday at the Prora-Rügen KdF holiday complex during the Third Reich but the buildings remain (unknown)

GERMAN AUTOBAHN NETWORK

Two of the most persistent myths about 1930s European fascism are that Mussolini made Italian trains run on time and that Hitler invented the idea of the autobahn, or motorway. The Nazis saw political and economic value in developing a motorway network across Germany and put considerable effort into motorway building after they came to power but they did not invent the idea and there were a number of precursors of the autobahn network.

The first was a private section of road, about 10km long, built near Berlin just before the First World War. It was the idea of a group of car enthusiasts who wanted to create a ‘car-only road’. In fact it was mainly used for testing cars and for motor sport. In 1926 an association had been formed to lobby for the idea of a motorway linking Hamburg, Frankfurt and Basel in Switzerland, the so-called “HaFraBa” initiative. Much planning had been done although no construction had started. In August 1932, five months before the Nazis came to power, a section of public motorway was opened between Cologne and Bonn. It was financed by the City of Cologne and opened by its Mayor, Konrad Adenauer, who was to become the first post-war Chancellor of West Germany. There were also a series of plans in various stages of preparation for motorway style roads in several other parts of Germany although none had got off the drawing board.

Part of the new German autobahn network in the late 1930s – Hitler, Speer and Todt were interested in the aesthetics of motorways as well as their practical benefits (US Library of Congress)

Prior to 1933, the Nazis had been lukewarm about the idea of motorways but, once in power, Hitler saw their propaganda and economic value. The notion of creating mobility across Germany for ordinary people through a modern motorway network and the production of affordable cars appealed to the Führer. Within days of coming into office, Hitler appointed his chief engineer, Fritz Todt, to design and begin a programme of ‘Reichsautobahn’ construction with a target of 1,000km of new roads each year.

In September 1933 Hitler marked the beginning of the Nazi programme of road building by shovelling dirt in a ceremony on the banks of the Main in Frankfurt – one of a number of motorway construction sites across Germany. The first section built under the Nazis was opened, amid great propaganda fanfare, between Frankfurt and Darmstadt in May 1935. Construction of motorways across Germany continued up to the early years of the war and by 1939 almost 4,000km had been completed. At the time, although much less than the original targets, this was one of the most extensive motorway networks built anywhere in the world.

Like almost everything about the Nazis there was a dark side to this investment in infrastructure. Working conditions for labourers were, by all accounts, grim and autobahn construction workers who went on strike often found themselves hauled away for interrogation. By the latter part of the 1930s the shortage of labour for the motorway programme necessitated forced labour and, during the war, forced labour from concentration camps.

The idea that the building of the motorway network was a key element in achieving full employment in Nazi Germany is questionable. Originally there had been exaggerated claims that the road building programme would create as many as 600,000 jobs but the true number was much lower – probably around 120,000. Full employment in the Third Reich only arrived once the massive rearmament programme began in the mid-1930s.

Another widely held notion about the Nazis’ affection for motorway building is that their real motive was military. The idea that they were primarily interested in creating the network for transporting people and materials in war is probably wrong. After the outbreak of war very little military use was made of the autobahn network as rail transport was seen as more useful.

Hitler digging foundations of one of the first sections of autobahn built after the Nazis came to power near Frankfurt, 1933 (Bundesarchiv, Unknown)

Todt, Speer and Hitler were interested in the aesthetics and saw the symbolism of motorways snaking across the Fatherland as something that unified the Reich. The standard design of the network, the rules about curves and intersections, were all part of creating an aesthetic that spoke to their vision of the Third Reich as a technological, people-friendly paradise enabling Germans to travel the length and breadth of their homeland. The development of the network was extensively covered by newspapers, in newsreels, on radio and on the new medium of television to convey this impression. Very few Germans could afford cars and Hitler’s dream of the ‘people’s car’, which became the VW Beetle, was only realised after the end of Nazi rule.

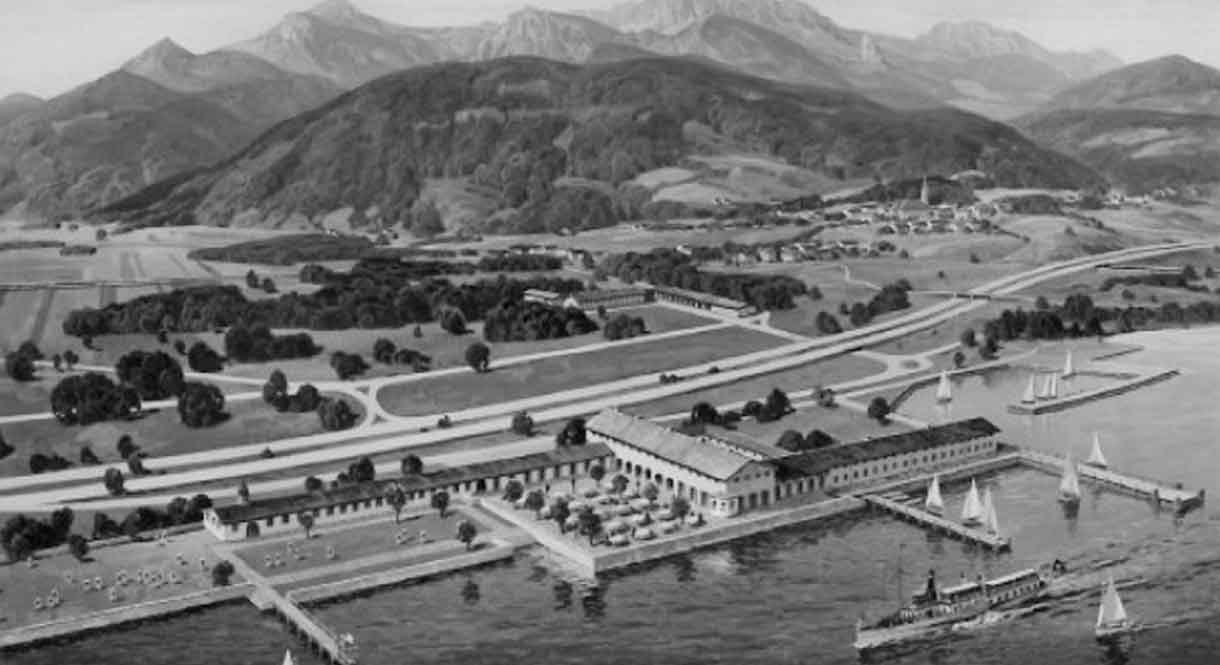

Providing pleasant areas for motorists to stop and rest was part of this overall approach. Hitler is alleged to have influenced the choice of location for what was in effect the world’s first motorway service station on the shores of Chiemsee in Bavaria on the Munich to Salzburg route. It was opened on 27 August 1937 with 520 seats, dining space for 350, an outside terrace able to accommodate over 1,300 people and an outdoor swimming pool; its popularity was so great that closure was forced on several occasions due to overcrowding. The Germans were keen to show it off and the British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, was entertained there in September 1938 during one of his visits to Germany prior to the Munich Agreement. After the war the site was used by the American military as a recreation centre until 2002. The buildings now have monument protection status and, since 2012, one has been used as a health clinic.

British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, and the German Foreign Minister, Joachim von Ribbentrop, visit Rasthaus Chiemsee on the Munich-Salzburg autobahn, September 1938 (Bundesarchiv, unknown)

Buildings of the former Rasthaus Chiemsee which is now a health clinic (Bayerische Landsamt für Denkmalpflege)

Chiemsee itself is no longer a motorway service area but the vast majority of the Reichsautobahn network constructed up to 1941 remains in use. Two years into the war all new motorway construction came to a standstill with resources diverted to the war effort. For most of the war very little private traffic was allowed on the autobahnen which were used for freight traffic – including moving military parts between factories. A few sections were closed as roads and used as military runways and some motorway tunnels became armaments factories (see Chapter Six). Towards the war’s end significant damage was done to the motorways both by retreating German forces destroying bridges and intersections attempting to stall the Allied progress, and also by the advancing Allies themselves; many surfaces were found to be inadequate for the weights imposed by convoys of military transport.

The legacy of the Nazis’ motorway building programme from 1933 to 1941 is really twofold. Firstly, the Reichsautobahn was the first proper motorway network in the world and many of the technical, aesthetic and other lessons learned in their construction influenced the development of high-speed roads elsewhere. Before and after the war engineers travelled to Germany to see it for themselves.

Among the international visitors was James Drake from Lancashire who was the leading light behind Britain’s first section of motorway which was opened near Preston in the 1950s. President Eisenhower is said to have been inspired to start the American interstate highways network as a result of seeing the German autobahnen at the end of the war.

Secondly, post-war Germany was bequeathed the beginnings of a motorway network far more extensive than in any other country, albeit one that was damaged and incomplete in 1945. The motorways built during the Third Reich era constitute about a quarter of the total German motorway network in the twenty-first century.

Of all the structures left by the Nazis, the motorway network is probably the least tainted by association. The motives behind the construction of the Reichsautobahnen were in part political and propagandist; they were part of the same hyperbolic vision for the ‘Thousand Year Reich’ which created the Prora KdF camp and the Nuremberg Rally Grounds. Significant sections of the motorway network were also constructed using forced labour. These factors, however, were not strong enough counterbalances to the power of pragmatic common sense to make use of this legacy in the rebuilding of Germany after 1945.

The German motorway network has, stage by stage, been expanded and completed. Both governments in a divided Germany resumed motorway building – West Germany more enthusiastically. But the division of the country produced some quirky legacies. Some routes were bisected by the border that divided East and West Germany and other unfinished routes were not completed because the division of the country made them unnecessary.

View of the first motorway service area – Rasthaus Chiemsee from the air, 1937 (Archiv Eckhard Gruber)

Remains of the so-called ‘Strecke 46’ section of uncompleted motorway near Gmünden am Main – part of an unfinished plan to link Hamburg and Lake Constance (Blueduck4711)

For example, the so-called Berlinka motorway, originally planned to link Berlin with Königsberg in East Prussia, was split between East Germany, Poland and the Soviet Union. Some segments of the road became virtually ‘ghost roads’ hardly used by any traffic and were tourist attractions in their own right as examples of Nazi architecture frozen in aspic. Since reunification most of this road, and many other disconnected sections of motorway, have either been upgraded or incorporated into local roads.

This was not inevitable; deep in the woods in the Lower Franconian Forest near Gmünden am Main almost fifty relics remain of a section of motorway started during the Nazi era but never finished. They are bridges, supports and other structures related to ‘Strecke 46’ or section forty-six of the planned Hamburg to Lake Constance autobahn. They stretch along a section of over 65km of the originally planned route of the motorway. When the road was completed post-war, as what is now the A7, it was decided to take a different route about 30km further east. Today tourists walk the route of ‘Strecke 46’ to see one of the more curious relics of the Third Reich.

HAUS DER KUNST, MUNICH, BAVARIA

It stands on the southern edge of the Englischer Garten, Munich’s largest park, and is scheduled to undergo a 60 million Euros redevelopment designed by the British architect David Chipperfield. However, the postwar history of the ‘Haus der Kunst’ has been marked by controversy about whether it should be retained at all given its origins as one of the very first monuments built by the Nazis.

Haus der Kunst, now a major art gallery of international significance, on the edge of the Englischer Garten in Munich (Andreas von der Au)

The ‘Haus der Deutschen Kunst’, ‘The House of German Art’ as it was originally called, was designed by Paul Ludwig Troost on Hitler’s orders and built between 1933 and 1937 on the site of a great glass palace used as an exhibition centre which had been destroyed by fire in 1931. The new building and its purpose were central to Nazi philosophy and propaganda and it played a key role in the Third Reich’s attempts to define and control cultural taste across Germany. It was opened on 18 July 1937 to show off what the Nazis regarded as Germany’s greatest art with its first exhibition entitled the ‘Great German Art Exhibition’.

This exhibition contained traditional landscapes and classical art featuring the human form and other works of art conforming to the Aryan ideals of the Nazi regime. It was repeated each year throughout the remainder of the Third Reich and its opening in the main hall of the ‘Haus der Deutschen Kunst’ was a major propaganda occasion for the Nazi leadership.

This opening exhibition was designed to be in marked contrast to an exhibition of so-called ‘Degenerate Art’ staged by the Nazis not far away in Munich at the Institute of Archaeology featuring the work of many artists, some of them Jewish, viewed by the regime as ‘degenerate’. These included many artists now regarded as some of the greatest of the twentieth century including Marc Chagall, Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky. More than a million people visited this exhibition – three times the numbers who visited the ‘Great German Art Exhibition’. Visitors appear to have been not only Nazi supporters and others who agreed with the official view of modern art as degenerate, but also people who had realised that this might be the last time to see modern art of this kind in Germany. The exhibition toured across Germany and was seen by a further million people.

When the Americans marched into Munich at the end of April 1945 much of the city lay in ruins but the Haus der Deutschen Kunst was largely intact. The last ‘Great German Art Exhibition’ had been held there the previous year and, as late as February 1945, Hitler was apparently ordering preparations for the next such exhibition later that year.

In another example of the pragmatism of utilizing Nazi buildings the Americans immediately converted it into a club for service personnel to include cooking facilities, a restaurant, a dance hall and several shops. Basketball courts were laid out on what had been the exhibition floors and jazz bands performed in the hall where the Nazis had once condemned modern culture.

In 1946 the building was renamed ‘Haus der Kunst’, and parts of it began to be used again for temporary art exhibitions including the display of Munich’s own art collection. Many of the exhibitions staged there in the early post-war years deliberately featured modern art which was seen as a form of denazification of the building. A Picasso retrospective in 1955 featuring his painting ‘Guernica’, a symbol of antifascism in art, was shown in Germany for the first time. Throughout the next thirty years the ‘Haus der Kunst’ became a major venue for international art exhibitions including many of the works of artists labelled ‘degenerate’ during the Third Reich. A series of structural changes, meanwhile, took place in the building which had the effect of further denazifying it. This approach was seen by many as a form of atonement for the origins of the gallery.

Haus der Deutschen Kunst in Munich – one of the first monumental buildings constructed by the Nazis and opened in July 1937 (Bundesarchiv, unknown)

It was only in the late 1980s, partly because the building was by then in need of serious renovation, that a debate started about its future. This coincided with more open consideration about the fate of Nazi architecture. Many people wanted to see the Nazi structure demolished but eventually the Bavarian Government decided on a partial renovation which was completed in 1993. In 1996, for the first time, there was a small exhibition in the ‘Haus der Kunst’ detailing its own history. More recently, since the start of a programme of so-called ‘Critical Reconstruction’ some of the physical changes have been reversed and the original features of the building have once again been exposed. This has been part of a process of coming to terms with the origins of the building as well as its necessary development as an international exhibition space – a process set to continue with the Chipperfield-led renovation expected to start by 2016.

As a footnote, the Americans may have moved out in 1956 but there is now an upmarket nightclub called P1 occupying part of the building. The name derives from its original American users – an abbreviation of the address of 1 Prinzregentenstrasse.

THINGSTÄTTEN

The Nazis perpetuated the idea of the ‘Volk’ community – the idea that all Germans, irrespective of their social status or their regional loyalties, were part of a common culture underpinned by quasi-spiritual roots deep in German history. Joseph Goebbels was also an exponent of the so-called ‘Blut und Boden’ (Blood and Soil) philosophy which emphasised the connections between the German people and their land.

One product of these rather vaguely defined ideas were the theatrical performances ‘Thingspiele’ staged in amphitheatres (Thingstätten) harking back to the old Germanic and Nordic concept of the ‘Thing’ – outdoor gatherings of people to celebrate their common heritage. Specially written productions were to be put on at a network of Thingstätten across the Reich to provide officially sanctioned entertainment for the masses.

The first of these amphitheatres opened in Brandberge in Halle in 1934 in what was supposed to be the beginning of a network of over 400 across Germany. In fact only around forty were ever built. The Nazi leadership appears to have rather lost interest in the idea. Insufficient productions were written and, above all, the idea of sitting outside in the often chilly German weather watching dramas of dubious interest was unsurprisingly not that popular. After a few years, the amphitheatres were designated as more general open air theatres putting on conventional dramas or were used to celebrate events like the summer solstice.

The Berlin Waldbühne was originally built as the Dietrich-Eckart-Bühne for the 1936 Olympic Games and is still in use as an outdoor arena (Gryffindor)

Ruins of Brandberge Thingstätte – the first open air arena built under the Third Reich and originally intended to be part of a network of 200 across Germany (Milena Waleska)

The Dietrich-Eckart-Bühne on the Berlin Olympic site just before the outbreak of war in 1939 (Bundesarchiv, A.Frankl)

Heiligenberg Thingstätte, Heidelberg remains like many Thingstätten across Germany and is now part of a public park (Bishkekrocks)

Nevertheless, one of the venues did play a central role in the 1936 Berlin Olympics (see Chapter Four). The Dietrich-Eckart-Bühne, designed by Werner March, was built on the Olympic site in Berlin. A production of a specially commissioned drama, Eberhard Wolfgang Möller’s Frankenburger Würfelspiel, was premiered on 2 August, the day after the opening of the Games. The amphitheatre was used for a number of Olympic events including boxing. Afterwards, like other Thingstätten, it was used more widely for choral and opera performances and played a role in the 1937 celebration of the 700th anniversary of the founding of Berlin.

Despite their origins as arenas of Nazi ‘worship’, a significant number of Thingstätten remain. The Dietrich-Eckart-Bühne in Berlin, now known as the Waldbühne, holds 22,000 people, has become a key venue for concerts and has hosted many of the most famous names of rock music since 1945. These include Jimi Hendrix, Eric Clapton, Barbra Streisand and, perhaps most notoriously, the Rolling Stones whose concert there in September 1965 ended in a riot with major damage to the arena.

The ruins of the first Thingstätte at Brandberge are designated a historical monument but many others, including the largely intact arena in Heidelberg, are still complete and used as public parks.

CARINHALL, SCHORFHEIDE FOREST, BRANDENBURG

In the middle of the Schorfheide Forest, close to the town of Eberswalde about fifty miles from Berlin, two entrance gates stand by the roadside. It is easy to miss them and nothing indicates their origins or significance. They are, however, virtually all that remains of an important Third Reich relic – the home of one of the most influential members of the Nazi elite.

Carinhall was built in stages from 1933 and designed by Werner March, architect of much of the Berlin Olympic site, as a grand hunting lodge for Hermann Göring who had purchased the land for his country retreat. The house was later dedicated as an official residence and its considerable upkeep costs paid by the state. After several enlargements it contained a bowling alley, a cinema, a swimming pool, and his vast model train set.

It was named after Göring’s first wife, Carin Fock, a Swedish divorcee whom he had married in 1923 but who died after a heart attack in 1931 at the age of forty-three in her native Stockholm. Göring was devastated by her death, named his country retreat after her and filled the house with pictures and mementoes of her. In 1934 her remains were brought to Germany and reinterred in a specially built mausoleum in the grounds of Carinhall. Hitler was among the leading Nazis who attended the ceremony.

Göring remarried and his second wife Emmy and their daughter, Edda, who was born in 1938, lived there for much of the war. Carinhall became the destination of much looted art treasure.

Today Carinhall does not exist. As the Russians advanced towards Berlin in early 1945 Göring ordered its destruction to prevent it falling into Soviet hands and it was dynamited by the Luftwaffe in late April. Göring, his wife and daughter, had already retreated to Berchtesgaden with the looted art. He committed suicide in October 1946 on the eve of his planned execution after being found guilty of war crimes at the Nuremberg Trials.

The surviving gates of Carinhall in the Schorfheide Forest – the country retreat of Reichsmarshall Hermann Göring (Brandenburg Landamt)

Hermann Göring welcoming guests in 1942 to Carinhall which was named after his first wife, Carin Fock (Bundesarchiv, unknown)

After the war the East German army blew up what remained of the buildings at Carinhall. Some of the remains of Göring’s first wife, Carin, were discovered in 1951 in the grounds and were returned to Sweden where they were reburied. In 1991 treasure hunters found more remains which were also sent to Sweden where they were DNA tested and confirmed as hers. The Brandenburg Land Government, worried about the site becoming a Neo-Nazi shrine, ordered the destruction of the remains of her tomb in 1999.

BERCHTESGADEN AND THE OBERSALZBERG, BAVARIA

Many homes of the most important Nazi leaders were on the Obersalzberg Mountain near Berchtesgaden in the most southerly corner of Germany in the Bavarian Mountains. Like Carinhall nearly all of these, which made up the mountain retreats and southern command headquarters of the Third Reich leadership on the Obersalzberg, have disappeared. Most were bombed at the very end of the Second World War or later destroyed by the occupying Americans or by the German authorities. Berchtesgaden and the Obersalzberg, nevertheless, remain inextricably linked to the Nazi era – an association which is now acknowledged by a Documentation Centre which draws hundreds of thousands of visitors to the area each year.

Hitler with Hermann Göring, Martin Bormann and Baldur von Shirach at the Berghof, Obersalzberg, 1936 (Bundesarchiv, unknown)

Haus Wachenfeld, later to be renamed the Berghof, with Nazi flag 1934 (Erich Wilhelm Krüger)

The Nazis’ love affair with the Obersalzberg began in the 1920s. Hitler is thought to have first visited the area after his release from prison after serving his sentence for his part in the failed Munich Beer Hall Putsch. He first rented a house there and, later in 1933 when he became Chancellor, bought what later became the Berghof. Existing property owners were forced to sell as the Nazi leadership bought or built houses there to be close to the Führer and the seat of power. The area became more than just a collection of homes and was in effect the southern seat of government and then of wartime command. It fitted well with Nazi ideals as it was rural, in Bavaria, and the birthplace and spiritual home of the movement.

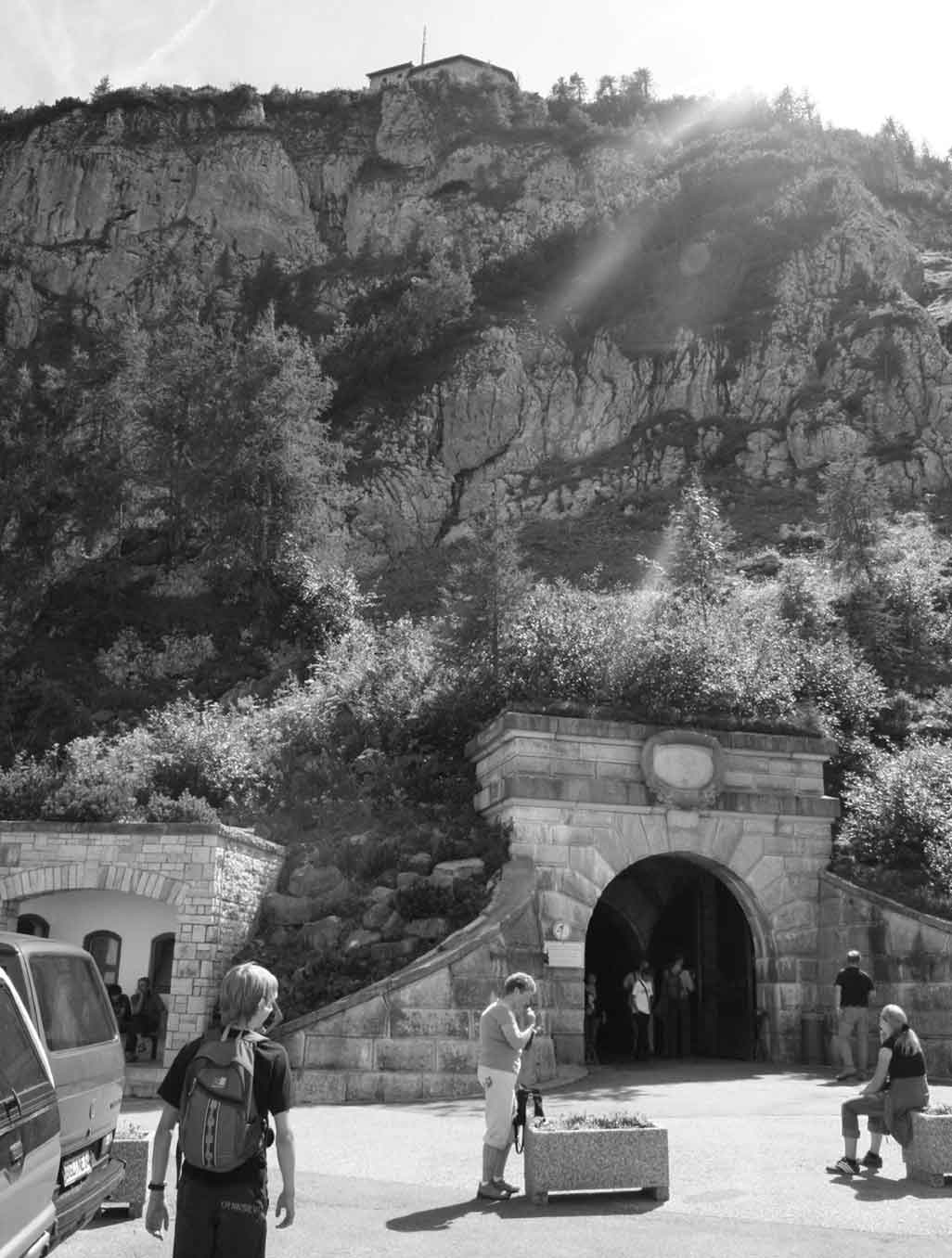

In fact many Nazi relics do remain. The most conspicuous of these could, possibly, be visited without realising its origins. During the summer months there is an almost constant stream of coaches and buses taking people up the winding road to the carpark of the Eagle’s Nest tearoom. From the carpark at the top of this road, visitors walk along a 100m tunnel carved out inside the mountain and then take a lift inside the mountain to reach the tearoom perched on top of the hillside. This, however, is no ordinary lift as it must be one of the best appointed in the world with brass plated sides, leather interior and elaborate fittings. On leaving the lift a visitor could be forgiven for thinking this is just another panoramic view across the mountains of southern Bavaria and Austria.

The Eagle’s Nest on the Obersalzberg – a fiftieth birthday present for Adolf Hitler and now an Alpine tearoom (Colin Philpott)

The well-appointed lift leading to the Eagle’s Nest, one of the few Nazi buildings untouched by Allied bombing on the Obersalzberg in April 1945 (Colin Philpott)

There is little or nothing to suggest that the Eagle’s Nest was in fact built as a fiftieth birthday present for Hitler from the Nazi party in a project masterminded by Martin Bormann. The Kehlsteinhaus, its German name taken from the name of the hill where it is perched, was completed in the summer of 1938 and formally presented to the Führer on his birthday on 20 April 1939. The whole project, particularly the access road which covered 6km involved five tunnels and climbed 800m, was a great engineering feat.

Apparently, however, Hitler was a rather ungrateful recipient of such a grand birthday present. He is thought only to have visited it ten times and never stayed long. Despite its prominence, the Eagle’s Nest survived Allied bombing and was also spared the planned demolition of other structures on the Obersalzberg in the 1950s – probably because its tourist potential was realised. It is now run by a trust and its profits are used for charitable purposes.

Other remaining relics from the Third Reich on the Obersalzberg include the Hotel zum Türken. Prior to the Nazis’ arrival on the mountain it was a successful hotel but the owner was forced to sell. The building became used as a headquarters for the security service which guarded the Führer and was severely damaged by Allied bombing at the end of the war. The family of the original pre-Nazi owners, however, fought a long battle after the war and eventually repurchased and rebuilt the hotel which remains in operation today. Like almost all the buildings on the mountain it was connected to the others by a network of underground tunnels which can still be visited by hotel guests.

The house containing Albert Speer’s architectural studio also remains and is now a private residence. In Berchtesgaden itself there are three notable remains from the Nazi era. The railway station was rebuilt during the Third Reich because it was the frequent arrival point for Nazi leaders and for visiting dignitaries. It was damaged in the war but rebuilt again in the 1950s maintaining the 1930s style. The Nazi-era Post Office also survives and a disused railway tunnel, not far from the station, can still be seen; a train containing part of Göring’s looted art collection was stored there towards the end of the war.

Many of the most iconic Nazi-era buildings on the Obersalzberg have gone. Perhaps the most famous was Hitler’s house, the Berghof. Originally Haus Wachenfeld, Hitler rented it during a stay in the 1920s but bought it in 1933 and enlarged it. With its panoramic windows affording sweeping views of the mountains and its balcony, it was the place immortalised in many photographs and film images – Hitler with Eva Braun, Hitler with his dog, and Hitler with a range of famous guests. These included the Italian leader, Benito Mussolini, the Duke of Windsor who had abdicated as King of England and, perhaps most famously, the British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain who was entertained there by Hitler during discussions prior to the Munich Agreement.

One of the few surviving remains of more than fifty Nazi-era buildings on the Obersalzberg (Colin Philpott)

Berchtesgaden Station rebuilt in the 1950s in 1930s National Socialist style (unknown)

Hitler greets British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain at the Berghof, September 1938 during discussions which led to the Munich Agreement (Bundesarchiv, unknown)

The Platterhof was a hostel for the many visitors who flocked to the Obersalzberg during the Nazi era to catch a glimpse of the Führer. After the war it became a hotel for American servicemen, the General Walker Hotel, but after the final American withdrawal from Germany it was demolished in 2001. Gone also are the various houses of other Nazi leaders including those of Göring and Bormann. More than fifty Nazi buildings had been located on the Obersalzberg including guesthouses, a theatre and SS barracks.

The events of one day, Wednesday 25 April 1945, explain why all but half a dozen of these are no longer standing. More than 300 British Lancaster bombers, supported by over 200 US planes and others from Canada and Australia pounded the Obersalzberg for over an hour. Only six people died in the raid but the damage to property was immense. Hitler’s Berghof, the SS barracks, the Hotel zum Türken, the Platterhof and Bormann and Göring’s houses were all either destroyed or badly damaged. Astonishingly, the Eagle’s Nest on top of the Kehlstein survived.

Earlier in the war Berchtesgaden had not been a bombing target; it was of little strategic importance and was beyond the reach of most Allied bombers until later. The raid on 25 April is thought to have been mainly motivated not by a desire to strike a symbolic target but because there was a belief among the Allied command that the Germans might make a last ditch stand there.

Extensive damage to the Berghof after Allied raids on the Obersalzberg on 25 April 1945 (unknown)

The Nazi Documentation Centre on the Obersalzberg built to explain the role of the area in the Third Reich story and opened in 1999 (Colin Philpott)

Decisions about the future of the Nazi sites on the Obersalzberg after the war were first made by the occupying Americans and, later, the Bavarian authorities. The ruins of Hitler’s Berghof were reputed to have been left untouched until the early 1950s as a warning of the dangers of Nazism. They were, however, demolished later and today only one side wall remains. As the property of leading Nazis and of the Nazi party was transferred to the Land Governments it ultimately fell to the Bavarian Government to decide what to do with much of the area.

In 1999, on the site of one of the former Nazi guesthouses, a Documentation Centre was opened which, like those at Nuremberg and elsewhere, tells the story of Nazi Germany and the particular part played by the Obersalzberg. The Bavarian Land Government has recently approved plans to extend the centre by adding a new building and developing a seminar centre. Of around 170,000 annual visitors to the centre about a quarter come from outside Germany.

SUMMARY

Many of the buildings and sites discussed in this chapter not only survived the collapse of Nazism but were actively maintained and developed in the post-war years. This is perhaps not surprising because most were rather useful. The motivation for building them had been part of Nazi ideology but these were not buildings or places associated with their terror. On the contrary many were specifically designed by the Nazis to be part of everyday life for German people. A motorway network, a grand art gallery in Munich and a large hotel in the Bavarian hills were legacies that postwar Germany could utilise. Forty or so amphitheatres around the country were maybe less useful but they could in many cases blend back into the natural surroundings from which they had been created.

The private houses of the Nazi leadership were perhaps never going to survive the end of the war; although those on the Obersalzberg may have been bombed by the Allies for mainly military purposes they would probably have been demolished anyway for symbolic reasons. Indeed, the ruins that remained of those not obliterated by bombing were eventually torn down.

The Prora-Rügen holiday complex on the Baltic Coast remains the most intriguing of these sites. It represents the ultimate triumph of pragmatism over symbolism with the current renovation of the holiday blocks that straddle almost 5km of coastline. This is returning them to their originally intended use as places to take a holiday, albeit one stripped of its Nazi ideology.