Showing Off to the World

(Vorführung auf der Weltbühne)

PREAMBLE

As the 1930s wore on, the Nazi leadership grew in confidence and, buttressed by propaganda, persuasion and terror, their hold over Germany strengthened. They began to flex their military muscles and their expanding international ambitions became clearer. Alongside rearmament and a variety of actions designed to exert Germany’s diplomatic rights they also sought to project Nazism onto the international stage mixing military threat with apparently peaceful showmanship.

Olympic Stadium Berlin with Olympic and Nazi flags flying for the opening ceremony on 1 August 1936 (Bundesarchiv, A.Frankel)

The Olympic Games of 1936, awarded before the Nazis came to power, provided a perfect opportunity to present a vision of the new Germany to the international community. The Winter Games, held in the Bavarian resorts of Garmisch and Partenkirchen, were a relatively modest taster for the Summer Games which took place in grand new facilities in Berlin.

The World’s Fair in Paris the following year provided another opportunity for grandstanding on the international stage. International posturing was also evident in the building of new airports in Germany’s two leading cities with Berlin’s Tempelhof and Munich’s Riem airports becoming its signature gateways.

A much more modest building associated with this phase of the Nazi era deserves a mention because, despite its relative lack of substance, the Führerbau in Munich, Hitler’s base for entertaining in Bavaria, played host to one of the most important diplomatic meetings of the twentieth-century – here the British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, put his name to the notorious and ultimately worthless Munich agreement.

GARMISCH-PARTENKIRCHEN WINTER OLYMPIC SITES, BAVARIA

The role of the 1936 Olympics in the history of the Third Reich bears some similarity to that of the German autobahn network. Like the motorways, the Olympics predated the Nazis. The 1936 Games had been awarded to Germany after a vote at the International Olympic Committee in 1931. Like the idea of a network of motorways, Hitler was initially sceptical about the value of the Olympics. In power, however, the Nazi leadership’s view changed because Joseph Goebbels recognised the enormous propaganda potential which the Games offered. Hitler became persuaded to adopt the Olympics and turn them into a massive state-sponsored project to project the new Germany onto the international stage.

Early in February 1936, just days before the Winter Games were due to start, the Nazis’ hopes of international recognition were threatened by a factor beyond their control – relatively warm winter temperatures in the Bavarian mountains. Luckily for the organisers, it snowed heavily immediately before the Games started on 6 February and Hitler arrived to open the Games amid rapturous cheers and heavy snowfall.

Potential international criticism of their racial policies was another reason for nervousness among the Nazi leadership prior to the opening of the Winter Games. By 1936 their persecution of Jews was well underway and there was little attempt to disguise it with anti-Semitic signs and slogans commonplace in most German towns and cities including in the twin-towns of Garmisch and Partenkirchen. The Germans knew that some countries, notably the United States, were already concerned about their anti-Jewish policies and talk of boycotting the Games was in the air – something they were determined to prevent.

View of the main skiing area at the 1936 Winter Olympics at Garmisch-Partenkirchen (Unknown)

Hitler watching the events at the Winter Olympics, Garmisch-Partenkirchen, February 1936 (Bundesarchiv, Willy Rehor)

Hitler saluting at the Winter Olympic Games, Garmisch-Partenkircken, February 1936 (Bundesarchiv, Heinrich Hoffman)

Hitler with Rudolf Hess and others at the opening of the Winter Olympics at Garmisch-Partenkirchen, February 1936 (Bundesarchiv, unknown)

Karl Ritter von Halt, the chair of the German Olympic Organising Committee of the Winter Games, was fearful that any anti-Jewish sentiment or violence in Garmisch-Partenkirchen would not only tarnish the Winter Games but also the main event – the Summer Games in Berlin six months later. He complained to the Nazi leadership and a swift clean-up and clampdown followed. Signs and slogans were removed and orders went out to Nazi storm troopers and others to lay off anti-Jewish violence for the duration of the Games.

Sonja Henie – triple gold-medallist figure skater from Norway at the 1936 Winter Olympics – her success at the Games launched a Hollywood career (Bundesarchiv, unknown)

The Garmisch-Partenkirchen stadium looks little changed from 1936 (Unknown)

Garmisch-Partenkirchen was something of a ‘forced marriage’ of two quite distinct towns nestling below Germany’s highest mountain, the Zugspitze. Hitler forced an amalgamation of the two towns as part of the preparation for the Games. The events lasted from 6-16 February and involved downhill Alpine skiing for the first time as well as the traditional Nordic winter sports. Twenty-eight nations took part in seventeen events and Norway won most medals including eight golds, three of them won by the figure skater Sonja Henie whose exploits at Garmisch were to launch a Hollywood film career. Henie, whose Nazi sympathies and admiration for Hitler were barely disguised, remains one of the most successful skaters of all time.

Many of the facilities built for the 1936 Winter Games still exist and Garmisch-Partenkirchen remains a leading skiing resort and winter sports venue. The most notable locations were the Ice Stadium built in Garmisch and the Ski Stadium in Partenkirchen. The Ski Stadium was built to hold 100,000 spectators and its central feature was the Olympiahaus containing a restaurant and VIP viewing platform from where Hitler and other dignitaries viewed the sporting action. The ski jump has been revamped twice since 1936 – in the 1950s and in 2007 but the overall feel of the resort is little changed since the Third Reich era.

The Winter Olympics in 1936 launched Garmisch-Partenkirchen’s future as a major winter sports venue and tourist destination, a role which has since brought it considerable prosperity. The ambiguities in the attitude of the town and its people to these Nazi legacies three-quarters of a century later were highlighted when Garmisch-Partenkirchen bid in 2011 with Munich to host the 2018 Winter Olympics. The bid was unsuccessful but, during the bidding process, the town was naturally keen to emphasise the sporting heritage of 1936 rather than its political legacy.

The literature surrounding the 2011 bid and the commemorative brochure produced on the sixtieth anniversary of the Games give maximum emphasis to the sport with little or no reference to the role the 1936 Games played in Nazi propaganda. Despite some discussion about a museum or exhibition in the town to tell the full story of the Games there has been no follow-up. After tourist complaints in 2006 that the town’s football stadium was still named after the organiser of the 1936 Games, the committed Nazi Karl Ritter von Halt, it was quietly renamed. Overall there seems to be rather less enthusiasm for acknowledging Garmisch-Partenkirchen’s role in the Nazi story than is found in many other German towns and cities.

Garmisch-Partenkirchen is still a thriving winter sports resort today and many of the facilities built in 1936 are still in use (Martin Fisch)

Arguments have been made that the survival, and indeed development, of the sporting facilities bequeathed by the 1936 Winter Olympics are tainted by association with the Nazis. The towns have derived great benefit from the Nazi investment in the games but the locations were not scenes of terror and to have destroyed the sites and the excellent sporting facilities would surely have been an act of unnecessary vandalism.

OLYMPIC STADIUM, BERLIN

The Olympic Stadium in Berlin highlights, even more than Garmisch-Partenkirchen, the dilemma associated with attitudes to the architecture of the Third Reich. Leaving from the U-bahn station and walking up the wide, gently-sloping piazza which leads to the stadium, there are two contrasting narratives on display.

The first is that this patch of land in the western suburbs of Berlin will forever be associated with one of the most ostentatious propaganda exercises undertaken by any twentieth-century regime. An international event, conceived as a vehicle for celebrating sporting excellence and fostering harmony between countries, was hijacked in the most cynical way by racist ideologues presenting a falsely serene view of their regime to the world. This view makes it difficult, if not impossible, to separate the architecture from the political motivation. The stadium and the other associated structures are irredeemably grim and foreboding. It is almost as though the walls have trapped within them the cheers of 100,000 people welcoming Hitler with Nazi salutes. Newsreel images of swastikas fluttering in the wind alongside the Olympic flag still seem to haunt the place.

View of the Olympic Stadium, Berlin from the air during the 1936 Summer Olympic Games (Bundesarchiv, Heinrich Hoffman)

The distinctive 1930s architecture of the Olympic Stadium, Berlin – the pillars surrounding the stadium (Colin Philpott)

The alternative view is that the Berlin Olympic Stadium is a superb example of 1930s architecture. Perhaps its most striking feature is the way it is deliberately sunk into the ground with the surface of the sporting arena 12m below ground level. The effect is to make it look smaller from the outside. Once inside the stadium itself the volume and scale of the arena below ground level become apparent. The neo-classical concrete symmetry of the stadium is both compelling and impressive and makes this an appropriate building for an event of truly international significance.

Hitler’s attempts to turn the eleventh modern Olympiad into an international showcase were not wholly successful. The Nazi script was threefold – meticulous choreography, faultless organisation and Aryan sporting superiority. The first two objectives may have been achieved but the third was not. Several decidedly non-Aryan competitors, most notably the black American runner and long-jumper, Jesse Owens, ignored the script and won medals under the noses of the Nazi leadership.

With this interpretation not only is the Berlin Olympic Stadium great architecture but the event for which it was built turned out to be, despite the intentions of the Nazi propagandists, an international sporting spectacle in the true tradition of the Olympics. The memories embodied in the stadium are therefore as much those of international sporting prowess as of Nazi propaganda. This is the legacy that is represented by the sites associated with the 1936 Berlin Olympics the honours board of which remains to commemorate achievements of Owens and others.

The Nazi regime unquestionably grabbed the Olympic opportunity presented serendipitously to them when they came to power with enormous enthusiasm. Prior to 1933 the German Olympic Organising Committee had been developing plans for the facilities necessary to stage the Games. The original proposal was to rebuild the 64,000 capacity Deutsches Stadion which had been opened in 1913 in the middle of the Grunewald Racecourse. Originally intended to stage the 1916 Olympics, awarded to Berlin but cancelled because of the First World War, that stadium had mainly been used for football during the 1920s and early 1930s.

Once he had embraced the propaganda possibilities offered by the Olympics, Hitler’s plans became more ambitious and he demanded a larger, grander stadium. Werner March, the original architect, was retained but commissioned to think big. The stadium was the centrepiece of an Olympic complex which also included an open-air amphitheatre, the Maifeld which could hold 250,000, the Haus der Deutschen Sport and a number of other venues. No resources were spared and the full force of the German state supported the project to ensure preparation of an impressive stage for the Games.

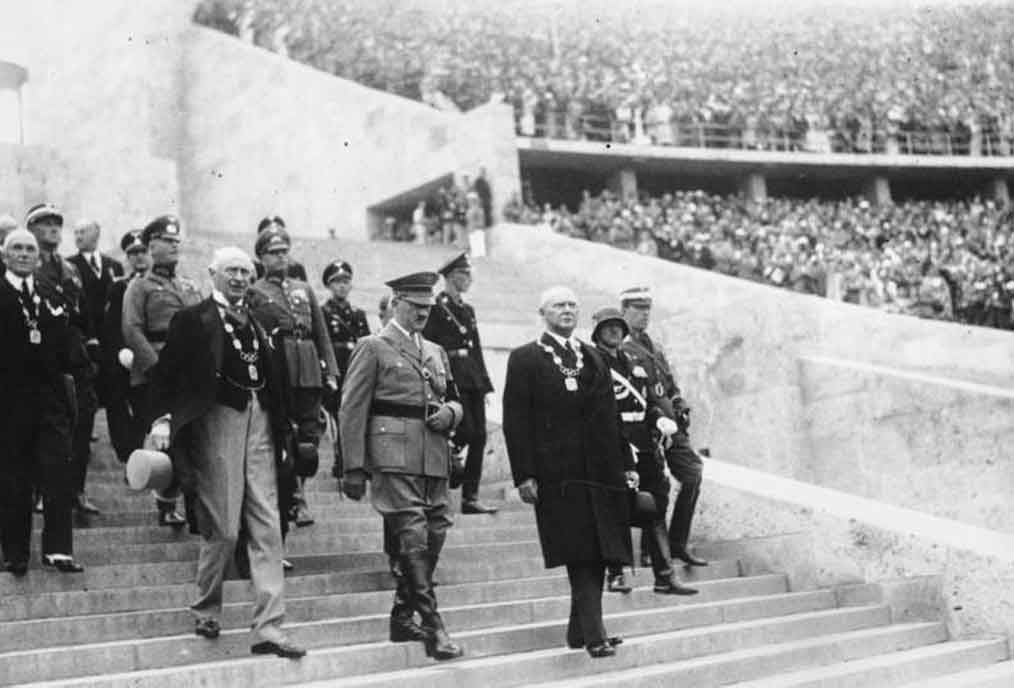

Hitler arriving for the opening ceremony of the Summer Olympics, 1 August 1936 (Bundesarchiv, unknown)

Saturday 1 August 1936 represents perhaps the apogee of Hitler and the Nazis’ peacetime straddling of the national and international stages. Hitler, now secure in power, arrived in the Olympic Stadium that afternoon to tumultuous cheers and Nazi salutes. With both the apparent plaudits of his people and international acceptance, however reluctant, he could bask in a glorious moment. As the teams of the competing nations streamed past the Führer during the opening ceremony some foreign competitors even made the Nazi salute.

Earlier controversies, however, had created doubt that the opening ceremony would ever take place. Concern had been expressed from various quarters around the world, almost from the moment that Hitler took power in early 1933, that the 1931 award had become a poisoned chalice. The obvious persecution of Jews was soon apparent and gave rise to talk of boycotts both by countries and by individuals. The Germans had given assurances that Jewish athletes would be allowed to compete in their team although eventually only one Jewish competitor, the fencer Helene Mayer, was selected to represent the home nation.

Such protests, however, faded – particularly after the United States Olympic Committee decided to participate. Some individuals from a number of countries refused to attend but they were few and far between. Controversy has persisted ever since about the attitude of the International Olympic Committee towards the Berlin Games. Should they have taken a tougher stand against Germany or even considered moving the Games elsewhere? With the benefit of hindsight, it wouldn’t be difficult to put up an argument that they should have done but, in the appeasement fuelled political atmosphere of the time, the decision was unsurprising. Furthermore there was the conviction that Germany would organise the Games very well.

For two weeks in August 1936, the world’s attention was on Berlin and the Germans put on a show. The organisation was meticulous and everything pretty much went like clockwork. Facilities were ready on time and the administration was excellent. The Games were the first to be televised to twenty or more public viewing screens in Berlin and Potsdam. The anti-Jewish slogans were removed and the regime assumed a deceptively benign face for the world; its excesses were largely put on hold for the duration of the Games.

Competitors from a number of nations made Nazi salutes on the podium at the 1936 Berlin Olympics (Bundesarchiv, Stempka)

Forty-nine nations took part in 129 events involving nineteen different sports. Germany won the largest medals tally (eighty-nine with thirty-three golds) but Jesse Owens won four golds in the 100m, 200m, long jump and the 4x100m relay. Hitler famously snubbed him despite these achievements.

Amid the destruction of Berlin in the final weeks of the war in the spring of 1945 the Olympic Stadium remained largely unscathed. Many of the other Olympic buildings were damaged but the stadium stood like a beacon amid the ruins of the city – one of the largest buildings to survive the Battle of Berlin. In the post-war political arrangements the stadium fell in the British sector of Berlin but the Olympic village was under Russian control. The Reichsportsfeld was used as the headquarters of the British military forces in Berlin. The Olympic Stadium itself became home of Hertha Berlin Football Club when the West German Bundesliga was formed in 1963. It was given protected historical monument status in 1966 and refurbished for the 1974 World Cup; partial roofing was constructed and three matches were hosted there.

Serious discussion took place after German reunification over the possibility of demolishing the Stadium which needed major refurbishment if it was to become the main national stadium of the new Germany – a factor in this debate being its association with the Nazi era. On 1 December 1998, however, the Berlin Senate approved a 242 million Euros redevelopment in preparation for what proved to be a successful bid to host the 2006 World Cup. Six matches including the final took place there.

Jesse Owens, who won four gold medals at the Berlin Olympics, confounding Nazi theories of Aryan superiority (Olympic Games Official record, unknown)

Since then the Olympic Stadium has hosted world-class sporting events including the 2009 World Athletic Championships when Usain Bolt established new world records, still standing in 2015, at both the 100m and 200m distances. The stadium, which hosts concerts and other events and remains the home of Hertha Berlin FC, hosted the UEFA Champions League Final in June 2015.

Interior of the Berlin Olympic Stadium after its refurbishment for the 2006 football World Cup (Colin Philpott)

Of the other Olympic structures, the Deutschlandhalle, which hosted boxing, weightlifting and wrestling, was finally demolished in 2011 despite its historical monument status. It had been rebuilt after the war as a multipurpose sports and entertainment venue but by the twenty-first century was outshone by other and newer Berlin venues. A purpose-built ice arena now stands on the site. The Maifeld is now a park. The swimming pool remains and is used occasionally. The Dietrich-Eckart Open Air Theatre is also still in use (see Chapter Two – Thingstätten). In 1984 a road near the stadium was renamed Jesse-Owens-Allee.

The most forlorn remains of the 1936 Olympics are a few miles away from the stadium at the site of the Olympic village. This was part of the Soviet zone of occupation and was used as an interrogation centre by the KGB. Since the Soviet departure in the 1980s it has remained a ruin. It can be visited but the only room that has been restored and preserved is the one occupied by Jesse Owens during the Games. Plans were announced in 2015 to redevelop the area for housing but it remains a sad monument to the genuine mixing of competitors that took place there in 1936 in defiance of the racist ideology of the hosts.

Berlin would of course welcome the opportunity to stage another Olympics free of the inevitable associations with the politics of 1936. In March 2015, however, the city lost out to Hamburg to be the nominated German bidder for the 2024 Games and so must await its turn.

Rudolf Hess at the Olympic Village several miles from the main Olympic site (Bundesarchiv, Heinrich Hoffman)

Remains of the dining room at the Olympic Village which is still largely derelict eighty years after the Games took place (Voice of America, unknown)

Remains of the Olympic Village swimming pool – there are hopes of a restoration of the site as a housing development (N.Lange)

Berlin’s Olympic Stadium has hosted many major sporting and cultural events since the Nazi era (Colin Philpott)

Christopher Hilton, in his study of the 1936 Games ‘Hitler’s Olympics’ says that the stadium and the other Olympic remains from 1936 retain a studious grandeur. ‘They still fulfil their original, cumulative purpose; to take your breath away.’ He speculates as to why this is the case ‘Perhaps it has to do with the perfect proportions; perhaps the imposing stonework; perhaps the knowledge that in August 1936 the world of sport had seen nothing to equal it; perhaps because here a poor black American sharecropper’s son brought the potential of the human body to an astonishing, immortal climax. Or perhaps because with hindsight we know what cataclysmic events came afterwards. Or maybe because Hitler built it and strode into it at a time when he truly stood at the centre of the world.’

This area of Berlin will forever be remembered for the Hitler Games but it was also the site of the achievements of Jesse Owens and many others at those Games. Many other great sporting and cultural events have been staged since 1936 at this site which has been remodelled to produce one of the most awe-inspiring stadiums in the world. Nazi architecture is not necessarily bad architecture just because it is Nazi architecture. It has been rightly preserved and reinvented.

THE GERMAN PAVILION AT THE WORLD’S FAIR, PARIS.

Most of the locations featured in this study are in Germany, or in what was Germany at the time of the Third Reich, but this structure at the heart of the French capital deserves a mention.

Between May to November 1937 the World’s Fair took place in the centre of Paris. The Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne (The International Exhibition of Arts and Technology in Modern Life) was designed to show off contemporary scientific and technological achievement with pavilions devoted to then new technologies like cinema, radio and aviation.

Forty-four participating nations each had a pavilion to show off their attainments. Germany and the Soviet Union were, almost certainly by accident rather than design, allocated prime sites opposite each other across the Seine from the Eiffel Tower. At first, as with other projects like the Olympics, Hitler was not enthusiastic about the World’s Fair but was persuaded by his chief architect, Albert Speer, of the importance of Germany being seen on this international stage.

Apocryphally, Speer found a copy of the design of the planned Russian pavilion when visiting the Paris site some months before the opening and decided to ensure the German pavilion would be taller than its Soviet rival. Whether true or not, the German pavilion indeed towered above the Soviet one. It was made of steel with a Bavarian marble surface topped by a giant German eagle. To ensure that it was built on time, and as Speer exactly required, more than 1,000 German workers were transported to Paris for its completion.

The German Pavilion at the World’s Fair, Paris, 1937 designed by Albert Speer (unknown)

The pavilion was dismantled after the exhibition and the fate of its materials remains a mystery.

BERLIN TEMPELHOF AND MUNICH RIEM AIRPORTS

Two airports in Germany’s two leading cities, both created as monuments to Nazism and both now closed to air traffic, are further examples of the grandiose architectural ambitions of the Third Reich. They are best known for events after the Nazi era – Tempelhof for the Berlin Airlift of 1948 and Munich-Riem for the 1958 air crash which cost the lives of many of the Manchester United football team and others. Although no longer airports, they both survive in the twenty-first century with new uses but with the Nazi connection ever-present.

The former Tempelhof Airport, south of the centre of Berlin, is yet another pre-existing site which was appropriated by the Nazis after their assumption of power for propaganda and practical reasons. Tempelhof was an airfield in the early years of flying before the First World War and the great aviation pioneer Orville Wright was one of the first to land there. The first operational terminal building dated from 1927 but, after 1933, Albert Speer commissioned Ernst Sagebiel to redesign Tempelhof in a style befitting the capital of the Third Reich.

Like many other Nazi projects, it was conceived on a monumental scale. The outcome was something far bigger than necessary for the actual needs of a 1930s airport. Its main feature is the quadrant-shaped terminal building over 1km long with lofty arrivals and departure halls. Building began in 1936 and continued into the early years of the war when the airport was one of the largest buildings in the world. Relative proximity to the city centre and the building of its own U-bahn station helped its development.

Planes on the tarmac at Berlin Tempelhof, 1948 around the time of the Berlin Airlift (US Air Force)

Berlin Tempelhof Airport Main Buildings which remain since the closure of the airport in 2008 (Alan Ford)

In the latter half of the 1930s, as commercial aviation grew in popularity, Tempelhof became one of the busiest airports in the world and compared with Paris-Le Bourget and London Croydon as the glamorous hubs of a new form of transport only available to the wealthy. At its peak Tempelhof received over 100 flights daily using the old terminal building while the new one was under construction – and that remained unfinished during the Third Reich.

Part of Tempelhof was built on the site of one of the earliest Nazi concentration camps, Columbia, which had opened in 1933 but which was closed three years later to make way for the airport.

During the Second World War, Tempelhof was used as a base for assembling Junkers Stuka dive bombers although it was not used as a military airfield. The Russians captured the airport during the Battle of Berlin in the last days of April 1945 and that July, under the terms of the Potsdam Agreement, the airport became part of the American occupation zone from where commercial flying resumed in February 1946.

Tempelhof’s biggest claim to fame began in June 1948. The western-controlled sectors of Berlin were surrounded by the Soviet-controlled sector of Germany. Land routes between West Berlin and West Germany had been agreed but, as tensions mounted between the West and the Soviet Union, these were blocked by the Russians. West Berlin could only remain connected to the West by the three air corridors which were part of the 1945 agreement. For almost a year the Western Allies organised a continuous stream of aircraft bringing vital supplies into West Berlin via Tempelhof before the Russians called off the land blockade in May 1949.

From the 1950s onwards Tempelhof developed as a major commercial airport peaking in the early 1970s with over five million passengers a year. It also retained a military role until the fall of the Berlin Wall led to the withdrawal of American forces in 1994.

By the 1990s Tempelhof’s position as Berlin’s leading airport was already weakening. Some airlines had transferred to Berlin Tegel and, by the mid-nineties, Tempelhof’s main traffic was smaller commuter flights. In 1996 plans were announced to create a single unified airport for Berlin based next to Schönefeld Airport; these required the closure of first Tempelhof and then Tegel airports. A non-binding referendum in Berlin failed to stop the closure and the last flights left Tempelhof at the end of October 2008.

Interior of main hall at Berlin Tempelhof – visitors can tour the building and see this remnant of Nazi architecture (Alan Ford)

Berliners enjoying Tempelhofer Freiheit Park which has been created as a public park on the site of the former airport (Berlin Tempelhofer Freiheit, Nic Simanek)

Tempelhof has since enjoyed a new lease of life. It is now a massive urban park known as Tempelhofer Freiheit, bigger than New York’s Central Park, and crowds flock there daily to enjoy Berlin’s ‘urban lung’. Concerts and sports events are staged and tours can be taken around the old preserved terminal buildings. The historical legacy of Tempelhof is also marked by a memorial to those who suffered and died at the Columbia Concentration Camp. The main U-bahn station serving the area was renamed to commemorate the Berlin Airlift – it is now called Platz der Luftbrücke. In 2014 a plan to build a large housing development on part of the site was defeated in a referendum. Berliners have taken Tempelhof to their hearts. Meanwhile, Berlin’s new airport is beset by delays and problems and not due to open until 2017. In 2015 both Tegel and Schönefeld airports remain in use.

Munich-Riem was also a product of the Third Reich designed as a prestigious gateway to the Bavarian capital. Work started in 1936 and the airport opened in 1939. Hitler flew in to Munich-Riem in November 1939 as one of the first passengers to use the airport. It replaced Munich’s previous airport at Oberwiesenfeld – an area nearer the city centre which later became the site for the 1972 Olympics. Immediately it was opened, Munich-Riem was pressed into service for military purposes although civilian flights continued through much of the war.

Remaining terminal building from Munich-Riem Airport which has been preserved as part of the redevelopment of the site since its closure as an airport (Florian Schutz)

One small section of the runway at Munich-Riem Airport can still be seen (Pahu)

New conference and events centre development of Messestadt Riem on the site of Munich-Riem Airport (Unknown)

On 9 April 1945 an Allied air raid virtually destroyed the airport but it was rebuilt and reopened in 1948 as a commercial airport. Its traffic grew steadily and there were various improvements over the years. As early as the 1960s, however, Munich recognised that it would eventually need a new airport as expansion at Riem would involve sacrificing nearby communities. Another thirty years elapsed before, in May 1992, Riem closed and was replaced by the new Munich Franz Josef-Strauss Airport.

In the early years after its closure Munich-Riem Airport was the scene of a lively alternative music scene hosting concerts and raves. The area has now been redeveloped as Messestadt Riem, a convention centre with associated housing and other developments. The control tower and terminal building of the old airport are preserved as historical monuments.

Munich-Riem Airport is most associated with the events of 6 February 1958 when a charter plane returning the Manchester United football team from a European Cup tie in Belgrade crashed on take-off. Twenty-three people died including eight members of the team. The cause of the crash was eventually established as slush on the runway. There is a memorial to the crash victims at the airport site.

FÜHRERBAU BUILDING, MUNICH, BAVARIA

In the early hours of 30 September 1938, the leaders of Germany, France, Britain and Italy signed an agreement on the second floor of number 12, Arcisstrasse, north of the centre of Munich. Two of the signatories believed that this culmination of several weeks of shuttle diplomacy would prevent another war. The meeting in Munich was the third visit to Germany in a fortnight by the British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, as he vainly sought to prevent conflict.

Exterior of the Führerbau building, Munich, 1938 where Hitler entertained guests when in the Bavarian capital (Bundesarchiv, unknown)

Neville Chamberlain, the French leader Edouard Daladier, Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini and the Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs Galeazzo Ciano in the Führerbau, September 1938 (Bundesarchiv, unknown)

Britain and France agreed to Hitler’s demands, backed by the Italian leader Mussolini, for the so-called Sudetenland (areas of Czechoslovakia with significant German speaking populations) to be ceded to Germany. Chamberlain believed that the agreement would appease Hitler and be the limit of his territorial ambitions – a belief that proved to be very wrong. The Czech government wasn’t invited to Munich and saw the agreement as a betrayal by Britain and France. Within a year Chamberlain’s hopes, and those of the French, had been dashed. Hitler ignored the terms of the deal and later invaded the whole of Czechoslovakia and, within a year, Poland; the world was at war again little more than twenty years after the war to end all wars had finished.

On his return to London after what became known as the Munich Agreement Neville Chamberlain claimed that he had secured ‘peace in our time’.

When I dragged my family round the streets of Munich to find 12 Arcisstrasse some years ago, they wondered why we had bothered to seek out such an ordinary building. The very ordinariness of the place where such a momentous act of diplomacy took place, however, accounts for its fascination. Imagining those four men gathered together in a simple room less than a year before they would be at war feels painfully poignant.

Interior of what was Hitler’s study at the Führerbau during the time of the Munich Agreement (Unknown)

At the time of the signature Arcisstrasse 12 was the Führerbau; it was designed by the architect Paul Troost and completed in 1934 as a building for entertaining by the Nazi leadership when in Munich. After the war the US occupation forces used it as a collecting place for the recovery of works of art looted by the Nazis. When it later reverted to the German authorities it became the home of the Hochschule für Musik und Theater (The University of Applied Sciences of Music and Theatre) and still performs that role.

There is, perhaps unsurprisingly, no plaque on the wall and no particular commemoration of the momentous events that took place in this building. However, since April 2015, the opening of the new NS-Documentation Centre around the corner on the site of the former Braun Haus (see Chapter One) has brought renewed attention to this area of Munich and its Nazi past. It is now possible to take a tour inside the building and to enter the room where the Munich Agreement was signed. It looks very much as it did on that fateful day more than three generations ago.

The group of buildings and sites discussed in this chapter demonstrate perhaps above all others in this study the relative disconnect that now exists between the reasons for their construction during the Third Reich and their continued subsequent existence. The principal purpose of constructing all these buildings was to show off Nazi Germany – vast Olympic facilities, grand new airports, a pavilion at an international exhibition and a more modest but highly significant entertainment building for the Nazi leadership.

With the exception of the German Pavilion at the World’s Fair, which was only ever intended to be temporary, the others remain and indeed are now enjoying new leases of life in many ways unrelated to their Nazi origins. Both the airports stopped being airports only because the demands of growing air traffic had made them unfit for purpose by the end of the twentieth century.

Most of the sites featured in this section are both fine and useful buildings and spaces. To have torn them down would have been hugely wasteful and a wanton attack on the country’s architectural legacy despite their Nazi provenance.

The Führerbau today – like many Nazi-era buildings which have found a new use – as the Hochschule für Musik und Theater (Colin Philpott)

Those relaxing in the parkland that once was Tempelhof Airport or watching a football match in the Olympic Stadium still talk about, and are aware of, the historic connection with the Nazis – and that link to ‘dark history’ may well be part of the reason for some visits seventy-five years later. None of these places, however, was directly associated with Nazi terror and all are also known for other reasons – the Berlin Airlift, the 2006 World Cup, the achievements of Jesse Owens. Their appropriate reinvention and adaptation allows us to feel at ease that they are still enjoyed today.