Enforcement

(Durchsetzung)

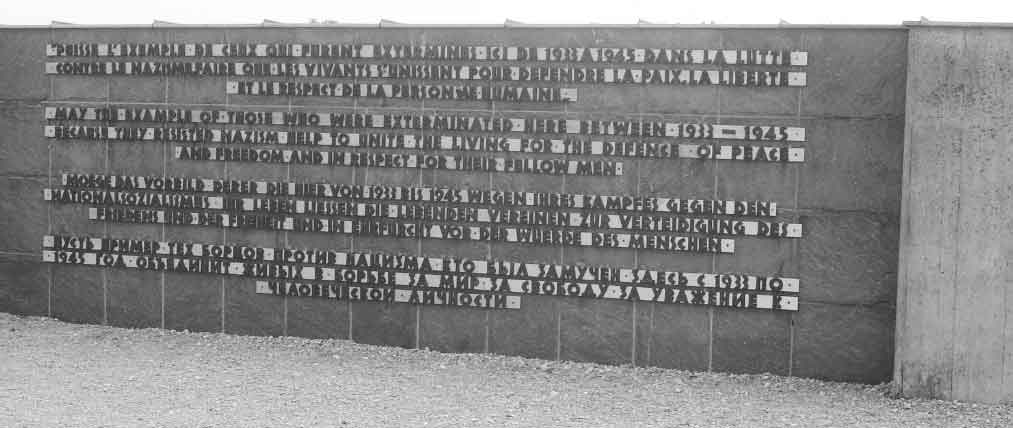

Dachau Memorial – Dachau had opened in March 1933 as the first permanent concentration camp established during the Third Reich (Colin Philpott)

PREAMBLE

The litany of concentration camp names which resonates down the years can almost anaesthetise us to the magnitude of the crimes committed at these places. The names are now so familiar that they trip off the tongue almost too easily. Auschwitz, Bergen-Belsen, Treblinka, Sachsenhausen, Dachau and many, many more – in fact an estimated 15,000 camps of one sort or another were built in Nazi occupied Europe.

Terror, intimidation, extra-judicial murder and later industrial-scale genocide, underpinned by a virulently racist ideology, were key characteristics of Nazi Germany. The places where these horrors took place have become the focus of much of the public remembrance of the evils of the Nazis in general and of the Holocaust in particular.

At this stage, during the peacetime Nazi years, our focus is on the places associated with enforcing control within the Reich. Embedding National Socialism in the German psyche through propaganda and material benefits was important but so was fear and terror and, in this chapter, we examine some of the places that played a key role in this.

Within weeks of taking power early in 1933, the very first permanent concentration camp was opened at Dachau near Munich to deal with political opponents. Much of the internal terror which became a hallmark of Nazi Germany was masterminded from behind the grim façade of the Gestapo Headquarters in Berlin. The Nazi war machine was planned from the new Air Ministry building in Berlin. Three military academies, or Ordensburgen, were set up around the Reich to train the Nazi elite. Finally the virtual destruction of the Reichstag (the German Parliament) by fire was a pivotal event in securing the Nazi hold on power.

DACHAU CONCENTRATION CAMP, DACHAU, BAVARIA

Its surroundings and ambience are highly relevant to a visitor to Dachau. The town of Dachau, about 20km north-west of Munich, is now part of what the Germans call the ‘Speckgürtel’, the ‘bacon-belt’ – in other words the affluent suburbs of the Bavarian capital. It feels very genteel and suggests twenty-first century German prosperity. Yet, amidst this quiet town, lie the remains of the place where, in many ways, the Nazi reign of terror across Germany, and much of Europe, began.

Dachau was probably chosen as the site for the first permanent Nazi concentration camp because of its proximity to the spiritual home of the movement, Munich. It was opened by Heinrich Himmler on 22 March 1933 on the site of a disused munitions factory within two months of Hitler coming to power. Its first prisoners were around 200 political opponents of the regime taken into ‘protective custody’ to ‘restore order’. The scope of its activities and the range of its prisoners gradually expanded. Homosexuals, Jehovah’s Witnesses, clergy, writers and other intellectuals, Sinti, Roma and, of course, both German and Austrian Jews were sent there as were prisoners of war. Dachau was run by the SS and became a model for subsequent concentration camps.

The Dachau concentration camp site first established as a memorial as a result of pressure from survivors and the families of those who died there (Colin Philpott)

Barracks at Dachau Concentration Camp shortly after its liberation in April 1945 (Sidney Blau, US Army)

Dachau was never an extermination camp in the way that Auschwitz and many others were but it was a place of torture, forced labour (mainly in armaments factories), medical experimentation and much more besides. It is estimated that over 200,000 people from thirty-four different nations were sent to Dachau and its 100 or so nearby subsidiary camps during its twelve-year history and that as many as 40,000 were killed or died during their captivity there. The overall treatment of US and British prisoners of war by Germany was generally in accordance with the Geneva Convention but Soviet prisoners of war were not afforded the same treatment and many ended up in concentration camps including Dachau. An estimated 5,000 Soviet prisoners of war held there were shot.

Even as late as March 1945, with the war lost, new prisoners were being sent to Dachau as the Germans moved inmates from camps near the front line to those further away. An estimated 10,000 of Dachau’s 30,000 inmates died between the autumn of 1944 and the end of the war in May 1945. Many were victims of malnutrition or one of the many typhoid outbreaks that occurred. Well into April 1945 Heinrich Himmler turned down a suggestion by the commandant of Dachau that the camp should be surrendered to the advancing Allies. Instead Himmler ordered that the remaining inmates either be marched to the Alps or murdered at Dachau if they were unable to travel. Thousands died in the last weeks before Dachau was liberated by American troops on 29 April 1945.

The discoveries by Allied troops as they reached Dachau are well documented but the appalling conditions had left many of the inmates at the point of death and many died in the weeks after liberation. Some prisoners turned on their guards and killed them and a military investigation found that American soldiers had summarily shot some of Dachau’s SS guards during the liberation after they had surrendered.

Bodies discovered at Dachau, April 1945 – an estimated 40,000 people died at Dachau either executed or through malnutrition, disease or as a result of medical experiments (US National Archives, unknown)

After its liberation Dachau continued as a detention centre – now with Germans being held on suspicion of war crimes. SS guards and Nazi officials were imprisoned there awaiting trial and it was only three years later that the site was handed over to the Bavarian authorities. A housing development was subsequently built to house refugees and homeless people.

Through the 1950s and into the 1960s pressure grew from survivors and families of those who had died in Dachau to establish a memorial there. In 1960 a chapel was dedicated on the site and in 1962 the Bavarian Government and the committee representing survivors, the Comite International de Dachau, agreed to establish a proper memorial on the site. In 1965 a new Documentation Centre was opened and the former camp was formally established as a memorial site.

Pile of prisoners’ clothes at the time of the liberation of Dachau in April, 1945 – many more prisoners died after the liberation through disease (US National Archives, unknown)

The establishment of a memorial at Dachau was mirrored by similar developments at other concentration camp sites across Germany and beyond. The twenty years taken was a reflection of two things.

Many camps were destroyed by the Allies or by the retreating Germans themselves. Many former concentration camps were, however, pressed into service as camps by the Allies either to hold suspected war criminals or, later, German refugees expelled from Eastern Europe. Only after those uses had expired did thinking start about the fate of these emotionally-charged places.

Furthermore the Allied occupation powers and, later, the post-war German authorities were not initially particularly interested in tackling the issue which was only pursued as a result of survivor pressure. For the Americans and the British the priorities were dealing with the Cold War threat from the former ally, the Soviet Union, and building up the West German economy. For the Germans, as they regained the levers of power in the 1950s, confronting the Nazi past was too difficult – particularly in conservative Bavaria. But for the concerted and long-running pressure from survivors of Dachau and the families of those who had died there the site would almost certainly not have been established as a memorial in the 1960s.

Since then, the Dachau site has been changed a number of times. In addition to a central memorial where the main roll-call area once stood there are now two reconstructed barracks and recreated foundations to mark the location of thirty other barracks buildings. The original barracks were demolished but not until the 1960s once they had served their usefulness in housing refugees. Also visible are the gatehouse, the watch towers and the crematorium; the maintenance building where the main Documentation Centre is housed and four religious chapels are also on the site. In November 2014 the iconic ‘Arbeit macht frei’ (Work sets you free) sign on the camp gates at Dachau was stolen.

Polish prisoners toasting liberation from Dachau by US forces on 29 April 1945 (Arland Mausser, US National Archives and Records Administration)

The preserved crematorium building at Dachau – part of the memorial established on the former concentration camp site (Colin Philpott)

Plans for the future development include bringing the herb garden, where prisoners were used as forced labour, into the memorial site as currently this is outside the area permitted to visitors. There are also plans for new exhibitions in one of the reconstituted barracks.

Dachau is not alone. Elsewhere in Germany, many of the main concentration camp sites are commemorated in some way either through a documentation centre or a simpler memorial. In most cases these memorials were established in the 1960s – usually through pressure from survivors. Now the costs of most of these so-called ‘victim sites’ are supported by the Federal as well as by Land governments.

I have visited Dachau twice and the simplicity of the memorial site is very moving. However chilling the recital of terror in the Documentation Centre, the scale of events at Dachau is best conveyed by walking around the bare but extensive grounds and seeing the reconstruction marking where thirty barracks once stood.

Visiting Dachau is also disturbing as an act of what has become known as ‘dark tourism’ – the visiting of places where bad things happened. One of the occasions I visited was during the summer of 2006 when the football World Cup was taking place in Germany. People in the football shirts of many nationalities were including Dachau on their tourist trail whilst in the country to watch the World Cup. On another occasion my visit coincided with a very large group of loud and disruptive students who did not seem to see the need to respect the place. It appeared to be just another stop on their journey.

Dachau provokes feelings that are both uncomfortable and reverential. The discomfort arises from questioning the motive for undertaking the visit. It is also a place of genuine remembrance. Professor John Lennon, with his colleague Professor Malcolm Foley, coined the phrase ‘dark tourism’ in the 1990s and he has visited and studied many similar sites across the world. He accepts that places like Dachau have become ‘commodified’ and are now part of tourist itineraries. He maintains, however, that this has merit in that some visitors at least will engage more deeply with such sites and the history they represent. He also believes that, for some, visiting a place like Dachau may offer their only learning experience about this element of a darker past.

The attitude of the people of Dachau, however, towards the camp and the memorial site is perhaps even more interesting than that of touring visitors. The general view is that for years local people ignored it. It was clearly a very uncomfortable part of their history and often portrayed as being someone else’s history. Dachau managed to convince itself that it was a victim of the Nazis – the town had not asked to have the camp there. In the 1930s, however, Dachau was a relatively poor town and many local people derived economic benefit from the camp which, of course, adds to the discomfort now felt; even changing the town’s name has been discussed.

Recently a much more open debate about the camp and the memorial has taken place with most local people now accepting it as part of their history. On her 2014 visit there the German Chancellor, Angela Merkel criticized her fellow countrymen for having turned a blind eye, and indeed acquiesced, to Dachau and to Nazi terror more generally – something which would have been inconceivable from a German leader twenty years previously.

‘Never Again’ Memorial – centrepiece of the Dachau memorial site (Colin Philpott)

GÖRING’S AIR MINISTRY, BERLIN

Detlev-Rohwedder-Haus, in the centre of Berlin – the home of the German Federal Finance Ministry (Hans Oberlack)

This is now Detlev-Rohwedder-Haus, an imposing structure along the Wilhelmstrasse in the heart of Berlin, housing the German Federal Finance Ministry. At first glance it is just another administrative building in the German capital but, like many state buildings erected in Germany in the 1930s, its interesting history is at the heart of four different systems of government across almost eighty years.

The building was constructed between early 1935 and the summer of 1936 to house the newly created Reich Air Ministry. Headed by Hermann Göring this new government department was set up by the Nazis in recognition of the growing military importance of air power. Military aviation had previously been supervised by a department of the army. This changed with the creation of the Reichsluftfahrtministerium and marked the beginning of the creation of the Luftwaffe which was to play such a significant role in the German war effort.

The headquarters of this new body were in the imposing classical style favoured by the Nazis. The architect was Ernst Sagebiel who also designed Tempelhof Airport (see Chapter Four). The building contained nearly 3,000 rooms over seven storeys, with a total floor area of more than 100,000 square metres. 4,000 people worked there and the frontage stretched for over 250m with its end wall adorned by a huge swastika and eagle.

It was within these walls that Hermann Göring masterminded the creation of the Luftwaffe as German rearmament gathered pace in the second half of the 1930s. After the outbreak of the war in 1939 the demands on the Ministry increased and, by all accounts, Göring’s control of it was haphazard. Control of aviation manufacture was later given to Albert Speer and production improved but too late to change the course of the conflict.

The building itself, though, survived the intense bombing of Berlin with only relatively minor damage and, despite its leading role in the Nazi war machine, it was immediately pressed into service by the Soviet occupation forces into whose zone it fell. The building was repaired, the Nazi insignia removed and it became the headquarters of the German Economic Commission, effectively the leading organisation in the Soviet zone, providing a new life for a grand building and its second use. In 1949 the creation of East Germany as the German Democratic Republic was marked in a ceremony inside the building; this took place in the room which had been the original Third Reich Ehrensaal or Honour Hall but which had had been converted into the Festsaal.

For the next forty years, the building was at the heart of the East German government machine and renamed the Haus der Ministerien housing various departments – its third use. Having served as an important location for the one dictatorship it then served another. Perhaps that caused the building to become the main focus of the uprising against the East German state in 1953 – one which was ruthlessly suppressed.

Reichsluftfahrtministerium or Göring’s Air Ministry, 1938 established as the Nazis recognised the importance of building up their military power in the air (Bundesarchiv, unknown)

After German reunification in 1990, having served two dictatorships and an occupier, it became a key location for a democratic regime. It housed the body that privatised the former state enterprises of the GDR and was renamed Detlev-Rohwedder-Haus in 1992 in honour of the chairman of that organisation who had been murdered by the German terrorist group, the Red Army Faction. Today the building houses the German Finance Ministry which moved there from Bonn after reunification.

The Air Ministry building is another example of a Nazi-era building which, for largely pragmatic reasons, has been preserved and put to new uses since 1945 and which has lost much of its Nazi taint. In 1945 Berlin well-designed buildings suitable for use by government agencies were in short supply so its survival is perhaps unsurprising.

ORDENSBURG VOGELSANG, SCHLEIDEN, NORTH-RHINE WESTPHALIA

ORDENSBURG SONTHOFEN, ALLGAU, BAVARIA

ORDENSBURG KRÖSSINSEE, POMERANIA, POLAND

Like the Air Ministry in Berlin three imposing structures which housed the military academies established by the Nazis to train the young elite of the Third Reich have all survived the intervening eighty years. This endurance, like Göring’s Berlin Luftwaffe Headquarters, is the result of pure pragmatism.

In 1933 Hitler announced that he wanted a network of centres established to train the Third Reich’s military elite of the future. Recruits had to be between twenty-five and thirty years old, confirmed Nazis, and of pure Aryan stock. Four centres were planned with each specialising in a different area of education. They were known as NS-Ordensburgen and recruits were to spend a year at each. The regime was hard and included mornings of study, afternoons of sport, physical education and military training, and more lessons in the evenings.

The imposing structure of NS-Ordensburg Vogelsang still dominates the skyline near Schleiden in North-Rhine Westphalia (VoWo)

Hitler at NS-Ordensburg Vogelsang in North-Rhine Westphalia – one of three elite academies established by the Nazis (Bundesarchiv, unknown)

Three of the centres, Vogelsang, Sonthofen and Krössinsee, were built and operated as intended. The fourth, Marienburg at Malbork Castle in what is now Poland, was a pre-existing building which was used for rallies and events but never operated in the same way as the other three.

Ordensburg Vogelsang in North-Rhine Westphalia specialised in teaching the Nazi ideas on race. It was planned on a vast scale although some plans went unrealised as a result of the outbreak of war. The centre included a community house, dormitories, extensive sports facilities and a Thingplatz auditorium but a planned Haus des Wissens, or library, was only partially completed. The complex operated from 1936 but, after the war started, it was handed over to the army and used as barracks.

After the war many surviving buildings were repaired and the area was used as a military training area by the West German Bundeswehr until 2006. The buildings can now be visited by tourists and they form part of the Eifel National Park. NS-Ordensburg Vogelsang is one of the largest surviving Nazi architectural relics anywhere.

Recruits marching in 1937 at NS-Ordensburg Vogelsang, which specialised in teaching Nazi ideas on race (Bundesarchiv, unknown)

Model of NS-Ordensburg Sonthofen which specialised in military training, administration and diplomacy (Bundesarchiv, unknown)

NS-Ordensburg Krössinsee in Pomerania is now in Poland and is still in use today by the Polish Army (Bundesarchiv, unknown)

NS-Ordensburg Sonthofen was built in 1934 in the Oberallgäu region of the Bavarian Alps and it specialised in military training, administration and diplomacy. After the war it was used first by French troops, then by the US Army and from 1956 by the Bundeswehr. It remains a military facility although on a smaller scale and is preserved as a historic site.

The third such centre was NS-Ordensburg Krössinsee near the city of Falkenburg, now Zlocieniec in Pomerania in Poland. Opened in 1936, it specialised in the development of character. Today it is used as a military facility by the Polish Army.

The historical significance of these sites is recognised in all three cases, particularly in the two sites still in Germany which visitors can access. As with many other Nazi buildings, their survival is again an example of pragmatism. These were useful, largely undamaged by war and were needed post-1945. Their original purpose was to indoctrinate the Nazi leaders of the future and, within their walls, a generation of young Germans was taught some of the most heinous Nazi ideas. They were not, however, sites associated with terror or genocide and consequently easier to assimilate into post-war life.

The post-war fate of the NS-Ordensburgen complexes is in marked contrast to the buildings that once stood on what was then Prinz-Albrecht-Strasse in the centre of Berlin. If there is one place that can be said to be the very nerve centre of Nazi terror and repression this was it. Number 8, Prinz-Albrecht-Strasse can rightly be described as one of the most notorious addresses in history.

The building had originally been the School of Applied Arts but in 1933 it was acquired and turned into the headquarters of both the Gestapo and the SS and, later, the Reich Security Service which brought together the various agencies of repression which existed in the Third Reich. Gestapo was the short name for the ‘Geheime Staatspolizei’, the secret police, which, under the leadership of Heinrich Himmler, became the main agency of terror in Nazi Germany and later in Nazi-occupied territories. The SS, or Schutzstaffel literally ‘protection squad’, grew from a small paramilitary unit originally used to protect Hitler and other Nazi leaders before they came to power. It was to become a major military and terror organisation of more than a million people and was responsible for the majority of Nazi war crimes.

Headquarters of the Gestapo, Prinz-Albrecht-Strasse, Berlin, 1933 – the Nazi terror machine was masterminded here (Bundesarchiv, unknown)

‘Topography of Terror’ Documentation Centre, Berlin built on the site of the former Gestapo Headquarters (Topography of Terror Centre)

The Prinz-Albrecht-Strasse building was both an administrative headquarters and an interrogation centre. In cellars beneath the building, the Gestapo employed a range of interrogation methods on German citizens suspected of opposition to the regime. Many Gestapo victims resulted from denunciations by fellow citizens and it is said that passers-by on the street could regularly hear screams coming from the cells.

The building was extensively damaged by Allied bombing and the ruins of this most notorious of Nazi structures were later demolished. The street constituted the boundary between the American and Soviet occupation zones of Berlin and the site of the Gestapo Headquarters was right alongside the Berlin Wall which was built by the East Germans to divide Berlin in 1961.

Today, however, a shiny new building stands where the Gestapo building once stood and the street, now fully reopened and renamed Niederkirchnerstrasse, is, incidentally, very close to one of very few remaining sections of the Berlin Wall. The ‘Topography of Terror’ Documentation Centre tells of the role of the Gestapo, the SS and the other agencies of Nazi terror. The centre was opened in 2010 but the first public acknowledgement of the history of the site had taken place almost a quarter of a century earlier before German reunification. East and West Berliners had collaborated to create a temporary exhibition on the excavated site of the former Gestapo cells – an outdoor display protected by a canopy to document events on the site.

A foundation was established, post reunification, to care for the site; work started on building a permanent exhibition but was delayed by financial problems and ongoing debates about how the site should be commemorated. One dispute concerned the fate of the basement cells where torture had taken place. Some argued that they should not be excavated but others disagreed. Some amateur archaeologists, meanwhile, even started digging to uncover these particularly chilling places of terror.

Walking route at the ‘Topography of Terror’ which includes views of the basement where torture took place during the Third Reich era (Topography of Terror Centre)

The Centre is now supported by both the Federal and Berlin governments. It contains exhibitions detailing the story of Nazi terror and also a fifteen ‘station’ tour of the site detailing specific remains of the building, including the basement cells, and their significance. There is a strong emphasis on the victims and on the stories of specific sufferers.

Visiting the ‘Topography of Terror’ represented for me one of the most powerful experiences at any Nazi site in Germany. The Germans refer to ‘perpetrator sites’ and ‘victim sites’ yet this is both. It details the horror of torture, of terror, and of the bureaucratic, institutionalised nature of the Third Reich terror machine. It provides a focus on the thinking of those who planned and executed that machine while treating the victims as more than nameless statistics. They are brought to life as real people and the geography is important. Not only is this the actual site from which these crimes were planned, and where so many were committed, but it is the very heart of the German capital. Here is a country detailing an episode of its own moral degradation just a stone’s throw from its seat of government and cheek by jowl with its new prosperity; the visitor is left both shocked and heartened.

REICHSTAG BUILDING AND KROLL OPERA HOUSE, BERLIN

This story is mostly about buildings and public spaces that the Nazis created or buildings and locations they appropriated or acquired. A discussion of the legacy of the architecture of the Third Reich would, however, be incomplete without reference to buildings they tore down or deliberately destroyed.

The wanton devastation of ‘Kristallnacht’ – 9 and 10 November 1938 – when over 1,000 synagogues were destroyed and more than 7,000 Jewish businesses were attacked probably constitutes the single most shocking act of state-sponsored destruction of the property of its own citizens in modern history. Attacks on Jews and their buildings were, of course, not confined to that night and were part of a theme of destruction undertaken by the Nazis against people and objects they considered ‘un-German’ – including the notorious burning of books and destruction of works of art.

The single most iconic building in Germany to be all but destroyed during the Nazi era was the very heart and symbol of German government and its fragile democracy – the Reichstag.

The seat of Germany’s fragile democracy during the Weimar Republic – the Reichstag in 1932 (Bundesarchiv, unknown)

The Reichstag well alight on the evening of 27 February 1933 – the Nazis used the fire as a pretext for violent anti-Communist persecution (US National Archives and Records Administration, unknown)

On the night of 27 February 1933, less than a month after Adolf Hitler had been appointed Chancellor, fire broke out in the Reichstag building. When fire crews arrived the building was well alight and, once it was under control, the damage was found to be extensive. Marinus van der Lubbe, a young Dutch communist, was arrested at the site. He and four other leading Communists subsequently went on trial charged with arson and with attempting to overthrow the government. The four were acquitted but van der Lubbe was found guilty and guillotined in January 1934.

Van der Lubbe claimed that he started the fire as a protest against fascist rule on behalf of the German working-class. Historians still argue about the case; there is disagreement about whether he acted alone and some historians believe that the fire may have been started by the Nazis themselves as a pretext for bringing in tough laws against political opponents. Whatever the truth they certainly used the fire to further their political ends.

On the next day President Hindenburg was persuaded by Hitler to sign a decree which severely restricted civil liberties including giving the government the right to ban certain publications. Hitler announced that the fire was the beginning of an attempted Communist takeover and there followed mass arrests of leading Communists across Germany. In the elections held a week after the fire in a frenzied anti-Communist atmosphere, the Nazis achieved an effective majority in the Reichstag for the first time.

The building itself was unusable after the fire. The newly elected Reichstag met not far away in the Krolloper (The Kroll Opera House) which became the substitute home of the German Parliament until the end of the Third Reich. The deputies meeting there quickly passed the Enabling Act which handed virtually unlimited power to Hitler. The Reichstag, thereafter, was merely a puppet legislature with no real power which met periodically into the war years until April 1942.

The Kroll Opera House, which had been built in 1844, was severely damaged in an Allied bombing raid on 22 November 1943, further damaged during the Red Army’s assault on the Reichstag in April 1945 and finally demolished in 1956. Today the area is grassed.

The Reichstag building, which had been built in 1894, lay in ruins at the end of the Second World War. Soviet troops famously planted the red flag on its roof to symbolise the capture of Berlin but the building had not by then been used for over a decade and was not to be used meaningfully again for a further four decades.

The building fell in the Western half of Berlin but was very close to the Wall. In the 1960s there was a partial renovation and it was occasionally used for one-off events. The two Germanys, however, each had their own parliaments – East Germany’s meeting in East Berlin and West Germany’s in Bonn.

After the fire in 1933 rendered the building unusable, the Reichstag met at the nearby Kroll Opera House, here in session in 1941 (Bundesarchiv, Schwan)

The Kroll Opera House was demolished after extensive bomb damage in 1945 (Bundesarchiv, Otto Donath)

Allied bomb damage at the Reichstag towards the end of the war in early 1945 (Sergeant Hewitt, British Army Film and Photography Unit)

German reunification was declared by Chancellor Helmut Kohl on 3 November 1990 in the Reichstag building but there was a long debate about whether to make Berlin once again the capital of the reunited country. The vote to do so in June 1991 was won by just eighteen votes – 338 to 320. The building was redesigned by the British architect Sir Norman Foster and the Bundestag met in the Reichstag for the first time in 1999. The glass cupola which is the best-known feature of the new design is one of the most visited tourist attractions in Germany.

The Reichstag, restored as the seat of the German Parliament after reunification in 1990, is now a major tourist destination (Colin Philpott)

SUMMARY

I draw three main conclusions about the legacy of this group of Nazi locations – locations associated with terror and the enforcement of Nazi rule in Germany particularly in the years from 1933 to 1939.

Pragmatism is again a primarily important factor. With the benefit of hindsight, the decision to use the very barracks at Dachau where prisoners had been incarcerated, tortured, and, in many cases, allowed to die, to house refugees and the homeless after the war seems cruel. Given the deprivations of post-war Germany with much of the country lying in ruins, however, it probably made sense. The reuse of the NS-Ordensburgen complexes for military training and the Air Ministry as post-war government buildings was also based on pragmatic reasons although easier because the buildings were not associated with terror.

Secondly, the story of how Dachau was first turned into a memorial site in the 1960s demonstrates the driving role played by survivors and families of victims of Nazi terror in establishing the idea of memorialising such sites. It was only later that the political establishment provided its supportive backing.

Thirdly, although the permanent exhibition ‘Topography of Terror’ was only opened on the site of the Gestapo Headquarters in 2010, the temporary exhibition established there in 1987 was one of the first to be established at so-called ‘perpetrator sites’. This perhaps reflects the special need felt in the German capital to acknowledge the shame of the Nazi period.