Elbeuf to Poissy

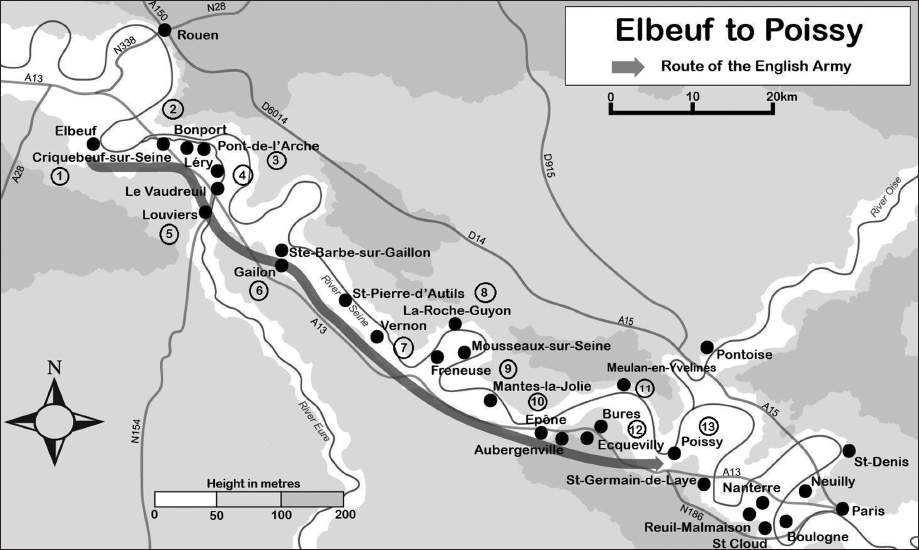

This tour covers the itinerary from the English departure from Elbeuf on 8 August 1346 until the crossing of the Seine at Poissy on 16 August. The tour covers a distance of 122km.

What Happened

The March along the Seine

Having failed to find a crossing at either Rouen or Elbeuf, the challenge now for Edward was to find somewhere else where he could cross to the right bank of the Seine. Between Elbeuf and Paris the main bridges were at Pont-de-l’Arche, Vernon, Mantes-la-Jolie, Meulan-en-Yvelines, Poissy and St-Cloud. A little over 2km to the east of Elbeuf there is a confluence of the rivers Seine and Eure. The Eure is a minor obstacle compared with the Seine, but for the next 10km it runs parallel to the Seine, with the two rivers separated by a narrow strip of land. It is only beyond Pont-de-l’Arche that the rivers start to diverge. At some point the Eure needs to be crossed if the Seine is to be followed. Judging by the itinerary of Edward’s army this crossing was made at or near Louviers. The first bridge over the Seine reached after leaving Elbeuf was, and still is, at Pont-de-l’Arche, which, in common with Vernon and Mantes-la-Jolie, was a walled town on the left bank of the river. It could be reinforced at will from the north provided the French held the bridge.

On Tuesday, 8 August the army passed through Criquebeuf-sur-Seine (Point 1) and past the twelfth-century abbey of Bonport (Point 2) close to the river Eure, and tried to storm the walls of Pont-de-l’Arche (Point 3). However, the town was very well protected with walls on all sides, including close up to the river Eure, and a castle within the town which would also have to be taken to gain access to the bridge. This would have been a tough nut to crack, and the local garrison under the command of Jean du Bosq, a royal official, held the English off long enough for elements of the main body of the French army to arrive and the assault was abandoned. While at Pont-de-l’Arche Edward received a message from Philip challenging him to settle their dispute by personal combat. The code of chivalry viewed refusal of such a challenge as dishonourable, but this was no more than political manoeuvring and, just as Philip had refused a similar challenge from Edward in 1340, the challenge was rejected with the response that the two kings would meet in battle at Paris. The English assault on Pont-de-l’Arche having been repulsed, the army moved on to lodge in the vicinity of Léry (Point 4) and Le Vaudreuil that night. As they went, the men continued to destroy, burn and loot across a wide band of territory.

The next day, Wednesday, 9 August, the English burned Le Vaudreuil and then pressed on to the next bridge at Vernon, passing through and burning Louviers (Point 5), a rich town noted for its cloth trade. Louviers was not walled, work only starting on defences twenty years later, and as a consequence it had probably been abandoned as the English approached. Having crossed the Eure in the vicinity of Louviers, there was a steady climb of 150m before the English came to Gaillon (Point 6) and the nearby village of Ste-Barbe-sur-Gaillon, standing on high ground, before a descent into the Seine valley. Both were looted and burnt but not before some fierce fighting in Gaillon, which was garrisoned with a castle standing on high ground in the north of the town. An unsuccessful assault on a castle on the Seine was recorded, possibly the one in Gaillon, which resulted in both Sir Thomas Holland and Sir Richard Talbot being wounded. An attempt by the town garrison of Gaillon to withdraw towards Vernon (Point 7) through the east gate turned into a rout with the English pursuing and cutting down the fleeing French.

Close to Vernon the English stormed and burned the unprotected village of Longueville, now the village of St-Pierre-d’Autils, and stormed its castle. Nothing remains of a castle here and it may be that this was a fort 4km to the north, known as Boute-Avant or Le Goulet, built by Richard the Lionheart and destroyed on the orders of Henry V in 1422, on the Île-des-Boeufs in the Seine. They massacred the garrison of the castle. The bridge at Vernon was well defended. It would have been necessary to take the town to gain access to the bridge, which was itself fortified. The bridge was constructed largely of stone but with a wooden section that could easily be destroyed, and passed through the castle of the Château des Tourelles at the eastern end, standing in the Seine with marsh behind. This was all too much for Edward’s men and they could get no further than the suburbs, which were fired along with the surrounding countryside.

During the next days the search for a crossing continued. On several stretches of the Seine from just downstream of Vernon until Poissy the left bank of the river runs close to high ground, with only a narrow strip of land in the valley suitable for movement. It is probable that for much of the march from the vicinity of Vernon to Poissy the bulk of the army took routes across the higher ground, with scouts staying in the river valley to reconnoitre potential crossing places. This would also have given the army the advantage of a more direct route, rather than following the sinuous course of the river.

On Thursday, 10 August the king stopped for the night at Freneuse and the prince’s division 3km further east at Mousseaux-sur-Seine. The formidable castle of La-Roche-Guyon (Point 8) is visible from the high ground 1.5km south of Freneuse. It must have looked a tempting target 7km away to the north-east, and on the same day a detachment under the command of Robert de Ferrers courageously crossed the river with a few men in a rowing boat and took the fortress. This was a quite remarkable feat since the castle, with two concentric outer walls, ditches and a keep on high ground had a reputation for being very strong. The garrison commander had clearly misjudged the situation and, thinking that he was under attack by the whole English army, surrendered both the castle and his men. Some forty or so French knights were killed or captured, although among the English Sir Edward Bois was killed by a stone thrown by the defenders. Having secured the word of his prisoners to pay ransoms in due course, de Ferrers returned to the safety of the other bank. It was while Edward rested at Freneuse that the cardinals came back to treat with the king once more. However, although this time they came openly from the French king, the terms on offer had not been improved and the discussions were fruitless.

The Seine, 3km upstream from Vernon, viewed from the right bank. The river runs close up against the hills and the bulk of the army would probably have passed across this higher ground with scouts following the river. (Peter Hoskins)

On Friday, 11 August the army pressed on to Mantes-la-Jolie (Point 9), now flying red banners symbolizing immediate readiness to give battle and fight to the death, but, finding several thousand French troops drawn up under the wall, passed on without attempting to take either the town or the bridge. Between Mantes-la-Jolie and Poissy the left bank of the river lies hard up against a steep escarpment in a number of places, and the itinerary of the army, with a stop for the Friday night at pône (Point 10) and Aubergenville and on the following night at Equevilly and Bures indicates that the major part of the army crossed the higher ground rather than attempting to follow the river. During the day the army had passed by Meulan-en-Yvelines (Point 11), where almost seventy-five years later Henry V was to set eyes for the first time on his future wife Catherine de Valois, daughter of Charles VI of France. The Earls of Warwick and Northampton had approached the town, which unlike Pont-de-l’Arche, Vernon and Mantes-la-Jolie, lay to the north of the river. There is an island in the middle of the Seine, which was strongly fortified. The bridge was in fact in two parts: the first linking the south bank, defended by a barbican, to the island and the second crossing from the island to the town. This would have been a difficult bridge to take, but to compound the problem the north end had been broken. Having been abused by the defenders of the barbican the English withdrew, but not until they had destroyed the suburb of Les Mureaux.

On Sunday, 13 August Edward came to Poissy (Point 13) and occupied the town, along with St-Germain-en-Laye with its royal hunting lodge. The English were now only 20km from Paris. Both Poissy and St-Germain-en-Laye had been abandoned, and the bridge over the Seine at Poissy had been broken. The king lodged in a new mansion built for Philip while the Black Prince settled into the old palace nearby. The French seem to have relied on the destruction of the bridge as sufficient defence, but they had not reckoned on the carpenters with Edward’s army. The English immediately set about rebuilding the bridge and later that day an initial span had been made with a 20m tree. The French received the news with disbelief, but men on the way from Amiens led by two minor barons, the Lords of Aufremont and Revel, were diverted to investigate. By the time they arrived it was too late and they found that the first of the English were already across the river. However, they were few in number and there was a risk of the French retaking possession of the north bank. Seeing the danger the constable, the Earl of Northampton, courageously led several hundred men across the perilous single span, only some 30cm wide, and by the time Aufremont and Revel were able to launch an attack the English bridgehead was well defended. The French were driven off, with perhaps 200 killed. In their haste to escape, the retreating French rode off two or three each astride un-harnessed cart horses, leaving behind twenty-one carts loaded with stone shot and crossbow quarrels and provisions. The carts were emptied and then burnt. Meanwhile the English continued to consolidate their position and to construct the replacement bridge. By the next morning a bridge capable of bearing carts was in place. There were no further serious attempts by the French to prevent the crossing of the army and on Wednesday, 16 August Edward started to move north towards the Somme. By the time he did so, the western outlying Parisian settlements of Nanterre, Rueil (now part of Rueil-Malmaison), Neuilly, Boulogne and St-Cloud had all been reduced to ashes.

The French Response

As Edward continued his march towards the Seine, the cardinals who had come to him at Lisieux were pressing Philip to offer terms which might secure peace. He agreed to restore the County of Ponthieu and lost territories in Aquitaine, and also offered a marriage alliance between the two crowns. However, the sting in the tail was that Philip still required homage from Edward for his lands held in France. The cardinals set out to meet Edward, accompanied by a French archbishop, to deliver Philip’s terms, but they were not optimistic of success. They also said that they did not believe that Philip was likely to make any further concessions. Edward sent them on their way saying that he would respond in due course, but that he would not delay his march while discussing the terms. In the event Edward moved north without attempting to engage Philip.

Philip now decided to concentrate his forces against Edward’s army with the objective of holding the English at the Seine. The troops at Amiens intended to counter Hugh Hastings were now called to join Philip, leaving only small detachments, and the Duke of Normandy was finally overruled and his army recalled to join the king, although the duke wasted valuable time before departing for the north trying to negotiate a truce in the south-west with the Earl of Lancaster.

When on Sunday, 13 August the English reached Poissy and St-Germain-en-Laye, they were within striking distance of Paris, and there was great alarm in the capital, and 500 men-at-arms of Jean de Luxembourg, King of Bohemia, were deployed in the streets to maintain order. Barricades were constructed, stores of missiles were gathered and preparations made to destroy suburbs outside the walls to deny them to the English. The French army was now substantial, with perhaps 8,000 men-at-arms, 6,000 Genoese and a large number of infantry. However, Philip faced a problem with their deployment. He could not defend Paris effectively without splitting his army, with the risk that entailed of one part being engaged by the whole of the English army. The bends in the river compounded his problems when it came to defending the bridges at Poissy and St-Cloud. To the north the distance between the two was around 60km, while the English only had to cover around a third of this distance. In addition, the walls of Poissy were in poor repair, making the defence of the town and the bridge even more problematic. Thus, he had abandoned the bridge at Poissy and concentrated his forces at St-Cloud, with his headquarters 15km further north in the abbey of St-Denis. On learning that the English were crossing at Poissy, Philip might have been expected to either advance from the north to counter the crossing or to cross the river himself and attack Edward from the south as he was engaged in crossing the river. He did neither. Instead he broke the bridge at St-Cloud and withdrew further north between St-Denis and Paris. The citizens of Paris could see the smoke rising from the fires in St-Cloud and St-Germain-en-Laye, as well as numerous hamlets and villages to the south of the capital.

While Edward was at Poissy, Philip, on 14 August, sent a message to challenge Edward to battle between 17 and 22 August. Two sites were proposed: one close to and south of Paris and another near Pointoise, 15km north of Poissy. In the event the challenge did not reach Edward before his departure from Poissy. However, Philip seems to have anticipated that he would have battle with the English at the first site since on Tuesday, 15 August he moved his army through Paris and towards the chosen battleground. The next day Edward was on the march away from Philip, heading to the Somme. Meanwhile, Philip was paying the price for drawing troops away from the forces originally intended to defend against the incursion of Hugh Hastings, and as Philip manoeuvred near Paris, Hastings and his Flemings were spreading destruction in the north.

The Route by Car

Leave Elbeuf on the D921 and follow this road through Criquebeuf-sur-Seine (Point 1) to Pont-de-l’Arche (Point 3). Bonport Abbey (Point 2) can be reached from the D921 near Pont-de-l’Arche. Take the D77 from Pont-de-l’Arche, and 1km after the junction with the D77e fork left onto an unnumbered road into Léry (Point 4). Leave the village towards Val-de-Reuil to rejoin the D77. At the junction with the D313 1km beyond Le Vaudreuil, turn right to follow the D313 into Louviers (Point 5). Leave Louviers on the D6155, turn right onto the D6015 near Heudebouville and follow this road through Gaillon (Point 6) to Vernon (Point 7). Now take the D915 to Bonnières-sur-Seine and then the D113 through Mantes-la-Jolie (Point 9). To visit La-Roche-Guyon (Point 8), turn left in Bonnières-sur-Seine and follow the D100 to the village. To rejoin the main route either retrace the route to Bonnières or continue on the D100 to join the D147 at Vétheuil and follow this road to Mantes-la-Jolie. After leaving Mantes, in Mézières-sur-Seine fork right and follow the D130 into Épône (Point 10). Leave the village on the D139 and rejoin the D113 through Ecquevilly (Point 12). To visit Meulan-en-Yvelines (Point 11) leave the D113 near Aubergenville and follow the D19 to Meulan. Return to the main route on the D43 at Equevilly. Rejoin and follow the D113 to the junction with the D153 near Orgeval. Follow the D153 into Poissy (Point 13).

The Route on Foot and by Bike

This tour is more or less along the valley of the Seine. There are stretches on quiet tracks and minor roads but there are extensive sections on quite busy D roads. There are often alternatives to these sections of busy road but at the expense of significant additions to distance. Some of the towns sprawl over a wide area and the route cannot avoid some drab, modern suburbs.

Leave Elbeuf on the footpath/cycle track which runs between the Seine and the D921. The path stays close to the river and diverges from the D921 about 1.5km after the road bridge over the Seine in Elbeuf. Stay on the path and, after a further 1km, follow an unnumbered road through Criquebeuf-sur-Seine (Point 1) to the junction with the D321. Follow the D321 and D77 past the abbey of Bonport (Point 2) into Pont-de-l’Arche (Point 3). Leave the town on the D77. A little over 1km after the roundabout with the D6015 at some traffic lights, just before a cemetery on the left, turn right to follow the Voie Impériale signposted forest track. After about 1.5km the track crosses the way-marked GR222A. After a further 400m turn left to follow a grass track across the D77 into Léry (Point 4). Make your way out of Léry on the Rue de Verdun and Route des Lacs to rejoin the D77.

The Voie Impériale has a well-maintained natural surface of packed earth and stone, with some loose stones. However, after the left turn to descend into Léry the condition of the path deteriorates markedly. The surface is grass, and muddy and potholed. The path also descends steeply in places. The forest track beyond the left turn on the walker’s route, now the Voie Blanche, appears to have a good surface, but an alternative route for cyclists is to remain on the D77 between Pont-de-l’Arche and Léry.

Follow the D77 through Le Vaudreuil. Immediately after crossing a disused railway line turn right onto the D313 and follow this road into Louviers (Point 5). From Louviers there is no choice but to follow the relatively busy D6155 and then the D6015 to Heudebouville. A little over 1km after the junction of the D6155 and D6015, fork right and follow the D177 and rejoin the D6015 in Ste-Barbe-sur-Gaillon. After 600m fork left and follow the road into Gaillon (Point 6). Leave the town on the D77. There is now a choice: either follow the relatively busy D6015 or take unnumbered roads to the south through Angreville, Habloville and Bailly to rejoin the D6015 near Le Goulet. Follow the D6015 and turn right onto the D73 near St-Pierre-d’Autils. Follow the D73, D527, Rue Jules Ferry, Rue Grégoire, Boulevard de Gaulle, Boulevard Jean Jaurès and D64 into Vernon (Point 7). It is possible to remain clear of the D6015 by turning south on unnumbered roads in Bailly and routing via St-Étienne-sous-Bailleul to rejoin the route at St-Pierre-d’Autils, but this adds considerably to the distance.

From Vernon cross the Seine on the D161, and in Vernonnet turn right to follow the D5 through Giverny and then right onto the D201. There are stretches of footpath parallel to the D5 which can be used. Follow the D201 through Bennecourt and across the Seine to join the D113 in Bonnières-sur-Seine. There are paths away from the D113, but they add significantly to the distance. The D113 is relatively busy, but for most of its length to Rosny-sur-Seine there are either wide verges or parallel paths. Through Rosny-sur-Seine there is a good track for cycles and pedestrians. On approaching the hospital complex on the left, turn left and follow Boulevard Sully. Turn right to follow the Rue Nungesser et Coli, continue straight on along the Rue du Dr Bretonneau, left into Avenue Albert Camus, and right into Rue des Garennes to Gassicourt. Turn left into Rue du Val de Seine, right into Rue Maurice Braunstein and then follow the Rue des Écoles into Mantes-la-Jolie (Point 9).

South-east of Mantes-la-Jolie there is a veritable spaghetti junction of busy roads. The quietest route out is along the river on the Quai des Cordeliers, and then, having passed under the D983, follow the Rue de la Tuilerie and the Allée de Chantereine to the junction with the D983. Immediately turn left onto a path which leads to the D113. This is a potentially busy road but it does at least have the benefit of wide cycle- and footpaths along the side. Follow the D113 to Mézières-sur-Seine. Fork right onto Rue Nationale a little more than 2km after crossing under the motorway and continue into Épône (Point 10). It is possible for the walker to avoid much of the D113 by turning right onto the D158 800m after joining the D113 on leaving Mantes-la-Jolie and then following unnumbered roads and the GR26 footpath through La Villeneuve to Épône.

The GR26 is not recommended for cyclists. The alternative to the D113 is to follow the D158 from the D113 through Boinville-en-Mantois and then to take the D139 into Épône.

Rejoin the D113 to the east of Épône. Follow this road to Ecquevilly (Point 12) and then on past Orgeval to the junction with the D153. Turn left and follow the D153 into Poissy (Point 13). The D113 is not a pleasant road to walk, but there are wide verges and paths and it can be used on foot with caution. There are alternatives from Épône via Ecquevilly, using minor roads and the GR26 but they involve substantial deviations from the direct route with consequent increases in distance.

The GR26 is not recommended for cyclists and it is impossible to avoid the D113 entirely between Épône and Ecquevilly and Ecquevilly and Poissy. The best alternative is to take the D113 initially from Épône and then just beyond Aubergenville follow the D14 and D19 to Flins-sur-Seine. Then follow unnumbered roads to rejoin the D113 about 1km to the west of Ecquevilly. Beyond Ecquevilly follow unnumbered roads via Morainvilliers, Montamets and Orgeval. Then rejoin the main route on the D153 into Poissy.

The church of Notre Dame in Criquebeuf-sur-Seine. (Peter Hoskins)

What to See

Criquebeuf-sur-Seine

Point 1: The bell-tower of the church of Notre Dame in the Rue du Pont des Alliés (GPS 49.306008, 1.097852) dates from the fourteenth century.

Point 2: The English army passed the abbey of Bonport on the approach to Pont-de-l’Arche. According to legend, this Cistercian abbey was founded by Richard the Lionheart in 1189 in thanks for his safe arrival on the river bank after getting into danger pursuing a deer. The church was destroyed during the French revolution but many of the monastery buildings remain. It is open to the public between April and September during the afternoons on Sundays and public holidays, and in July and August every afternoon except Saturday: www.abbayedebonport.com, Rue du Générale de Gaulle, Pont-de-l’Arche (GPS 49.306016, 1.140395).

Bonport Abbey. (Peter Hoskins)

Pont-de-l’Arche

Point 3: There are a number of vestiges of the defences of the town. The Tour de Crosne, private property but visible from Quai Maréchal Foch (GPS 49.306088, 1.153502), has a thirteenth-century base with the upper part having been restored by the architect Viollet le Duc in the nineteenth century. The towers of Tour St-Vigor and the Presbytère are also visible from the Quai Maréchal Foch (GPS 49.305945, 1.154693 and 49.305814, 1.155573). Parts of the gate at the Port de Crosne in Rue de Crosne (GPS 49.305004, 1.153532), and the well-preserved Tour de Bailliage near the Place du Souvenir (GPS 49.304345, 1.153766) also survive.

The Tour St-Vigor on the ramparts of Pont-de-l’Arche. (Peter Hoskins)

Léry

Point 4: The church of St-Ouen is in Place de l’Église (GPS 49.285740, 1.209400) with elements from the eleventh and twelfth centuries.

Louviers

Point 5: The church of Notre Dame in rue Pierre Mendes France (GPS 49.212906, 1.169671) has some minor elements from the eleventh to thirteenth centuries, but its most notable feature is the bell-tower, of a distinctly military character, built later in the Hundred Years War in 1414.

The church of St-Ouen in Léry. (Peter Hoskins)

The church of Notre Dame in Louviers. (Peter Hoskins)

Gaillon

Point 6: The present château in Gaillon, in the Allée du Château (GPS 49.160839, 1.329999), was built on the site of the earlier castle in the sixteenth century. Its dominant position above the town is evident. It is open between April and October, see the town website (www.ville-gaillon.fr) for opening hours.

The château of Gaillon. (Peter Hoskins)

Point 7: Vernon has a number of medieval buildings, including the collegiate church of Notre Dame in Rue Carnot (GPS 49.093274, 1.485931), the twelfth-century castle keep, the Tour des Archives in Rue des Écuries des Gardes (GPS 49.093826, 1.484151), and numerous domestic buildings with Rue Potard (GPS 49.093956, 1.484983) having fine examples of half-timbered buildings: see www.vernon27.fr/Decouvrir-Vernon. In Vernonnet, on the right bank of the Seine and close to the modern bridge (GPS 49.097982, 1.489200), stands the Château des Tourelles and the remains of the old bridge, together with a mill. The château is thought to have been constructed by King Henry II.

La Tour des Archives in Vernon, formerly the keep of the castle. (Peter Hoskins)

The remains of the medieval bridge at Vernon in the suburb of Vernonnet. (Peter Hoskins)

Vernon, Château des Tourelles in the suburb of Vernonnet. (Peter Hoskins)

La-Roche-Guyon

Point 8: A renaissance château (GPS 49.080985, 1.628575) now takes pride of place, but the keep of the twelfth-century fortress still stands. The château is open throughout the year. Opening hours vary considerably with the season: www.chateaudelarocheguyon.fr.

Mantes-la-Jolie

Point 9: There are numerous buildings in Mantes-la-Jolie surviving from the Middle Ages. The priory church of Ste-Anne de Grassicourt in the Impasse de Ste-Anne (GPS 49.002271, 1.697850), 2km northwest of the town centre, would have been outside the town walls. Within the walls were the church of St Maclou, of which only the tower survives in the Place du Marché au Blé (GPS 48.991038, 1.717328), and the collegiate church of Notre-Dame in Place de l’Étape (GPS 48.990532, 1.719480). The medieval walls and gates of the town were improved substantially twice during the Hundred Years War, between 1365 and 1373 and again between 1419 and 1449 under the English occupation. There are several elements of these medieval fortifications which survive: the Port du Prêtre (GPS 48.990055, 1.721755) and a watch tower and a stretch of wall (GPS 48.990055, 1.721755) in the Quai des Cordeliers, a length of wall below the site of the castle in the Rue des Tanneries (GPS 48.989411, 1.721774), a tower, the Tour St-Martin, in the Rue des Martraits (GPS 48.987048, 1.718701), and the site and footings of the gate known as the Chant à l’Oie in the Rue Porte Chant à l’Oie (GPS 48.992484, 1.715910).

The priory church of Ste-Anne de Grassicourt in the suburbs of Mantes-la-Jolie. The nave was restored after damage in 1944. (Peter Hoskins)

The twelfth- and thirteenth-century collegiate church of Notre Dame. (Peter Hoskins)

A surviving gate in Mantes-la-Jolie, named the Port du Prêtre in memory of an attempt by a priest to retake the town from the English in 1421. The gate appears lower than it would have been in the Middle Ages, having lost some height with the construction of quays along the river in the nineteenth century. (Peter Hoskins)

The perimeter tower of St-Martin. (Peter Hoskins)

Épône

Point 10: The church of St Béat in the Place des Fêtes (GPS 48.955399, 1.813884), although restored extensively in the nineteenth century, dates from the eleventh, twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

The church of St Béat in Épône. (Peter Hoskins)

Meulan-en-Yvelines

Point 11: Meulan is predominantly to the north of the Seine. The medieval bridge passed across an island, with the northern part known as the Petit Pont and the southern section as the Grand Pont. The northern section, also known as the Pont aux Perches, survives (GPS 49.004061, 1.910006). The church of St Nicholas, with elements from the twelfth century, is in Rue de la Côté St Nicholas (GPS 49.006318, 1.907843).

Ecquevilly

Point 12: The church of St Martin, restored over the centuries but originally built in the twelfth century, is in Place Henri Deutsch de Meurthe (GPS 48.949814, 1.922657).

The church of St Martin in Ecquevilly. (Peter Hoskins)

Poissy

Point 13: There has been a bridge over the Seine at Poissy since the time of Charlemagne. By the thirteenth century the bridge was in stone. The river was much wider in the fourteenth century and the bridge had thirty-seven arches; an idea of the width of the river in former times can be gained by looking at the distance covered by the remaining seven spans. In the fourteenth century there was a mill in the centre of the bridge, built in 1230 on the orders of Queen Blanche of Castile, wife of Louis VIII. The bridge was much modified over the centuries, with the addition of fortifications in the seventeenth century, and survived until destroyed by allied bombing in 1944. The remains of the old bridge are near the Rue de la Gare (GPS 48.933185, 2.037928).

Poissy was an important town for the Capetian dynasty, and the future King Louis IX was baptised in the twelfth-century collegiate church of Notre Dame, in Rue de l’Église (GPS 48.929653, 2.038016), in 1214.

The fourteenth-century gates of the Dominican priory, founded in 1304, survive in Rue de la Tournelle (GPS 48.928491, 2.037929), and there are some vestiges of the walls of the priory close to the junction of Rue de la Tournelle, and the Avenues Blanche de Castille and des Ursulines (GPS 48.926544, 2.038405). Edward is said to have lodged in the priory during his stay in Poissy.

The old bridge at Poissy. (Peter Hoskins)

The fourteenth-century gates of the Dominican priory in Poissy. (Peter Hoskins)

A very short stretch of the medieval city walls is near 5 Boulevard Louis Lemelle (GPS 48.927122, 2.045000). The castle is said to have been burnt down by the Black Prince before his division moved on to St-Germain-en-Laye. It was so badly damaged that the ruins were demolished on the orders of King Charles V in 1369.

The only remaining stretch of the medieval walls of Poissy. (Peter Hoskins)

Maps at 1:25,000 and 1:100,000 scales Published by the Institut National de l’Information Géographique et Forestière (IGN) www.ign.fr |

||

Cartes de Randonnée – 1:25,000 |

||

2012OT Forêt de Bord-Louviers, Elbeuf, Les Andelys |

2113O Vernon |

2114E Aubergenville, Guerville |

2013E Pacy-sur-Eure |

2113ET Mantes-la-Jolie, Boucles de la Seine, PNR du Vexin Français |

2214ET Versailles, Forêts de Marly et de St Germain (also Tour 4) |

TOP 100 – 1:100,000 |

||

TOP100117 Caen/Evreux (also Tour 2) |

TOP100108 Paris/Rouen (also Tour 4) |

How to Get There and Back by Public Transport

The Paris airports are convenient for this tour and are well connected to the city centre for onward travel by rail to Elbeuf. Ferries run from Portsmouth to Caen-Ouistreham and Le Havre. Railway services for this tour are provided by SNCF Basse-Normandie, Haute-Normandie and the Île-de-France Regions. Caen and Le Havre have main-line railway stations. There is a bus service between the port of Ouistreham and Caen (www.twisto.fr) but this does not operate during the evenings. There are buses from the ferry port in Le Havre to the railway station but this is only a few minutes’ walk away. There is a train service from Caen to Elbeuf (Région Basse-Normandie) and Le Havre to Elbeuf via Rouen (Région Haute-Normandie). Elbeuf is accessible from Paris via Oissel. Regional trains from the Haute-Normandie Region provide a service to Pont-de-l’Arche, Louviers (bus), Gaillon-Aubevoye (2km north of Gaillon), and Vernon-Giverny. The Île-de-France Region, also known as the Transilien, has an extensive network beyond Vernon, including Bonnières, Mantes-la-Jolie and Poissy. Timetables and route maps can be found on www.transilien.com. Tickets cannot be reserved for trains and buses on Transilien services.

Where to Stay and Where to Eat

The valley of the Seine is relatively densely populated and places to find refreshments are more plentiful than on other parts of the itinerary. Refreshments can be found at: Elbeuf, Pont-de-l’Arche, Criquebeuf-sur-Seine, Léry, Le Vaudreuil, Louviers, Gaillon, St-Pierre-d’Autils, Vernon, Épône, Ecquevilly and Poissy.

The local websites below give information on accommodation and refreshments for this tour: