Chapter Five

The Worst Place on Earth

Meandering through the streets of pyongyang, one cannot help but be impressed by its wide thoroughfares and massive structures. The capital city of North Korea is a carefully manicured and organized piece of urban planning. Like most Communist cities, it is built to impress with large plazas, iconic architecture, and scenic vistas. There is no litter on the streets and no graffiti. There are no homeless as you might find in any major city in the West. The air is clean. There are no traffic jams. One afternoon, as I was being driven back to my guesthouse from the foreign ministry, I watched children walking home from school, like kids everywhere. Their uniforms were a little disheveled after a day’s use, and they were laughing and joking happily as they chased each other down the sidewalk. Office workers were smoking cigarettes as they waited for the bus. Women, not dressed extravagantly but also not dressed poorly, were strolling home with shopping bags full of purchases made at the local store. Passing the main entrance to Kim Il-sung University, I was reminded of the university where I teach. Not in the sense that Kim Il-sung University is surrounded by multimillion-dollar Georgetown townhouses, but in the sense that one saw college-age students who looked carefree, full of enthusiasm, and welcoming of life’s opportunities. Every student had a clean-cut and well-kept appearance (no grunge look in Pyongyang!).

SOCIALIST PARADISE

Looking at life in Pyongyang, one hardly gets the impression often given in the Western press that this is a country on the verge of mass starvation and collapse. There is no sign of conspicuous wealth, but also no sign of poverty. On the contrary, it looks like a modest but well-functioning population that seems quite content living its everyday lives. I thought to myself, “I guess this is their Socialist paradise.” Some who have traveled to North Korea point to this scene that I have described to discount all of the claims of human rights abuses in North Korea. They argue that people are well taken care of. They argue that those who want to try the North Korean leader in the International Criminal Court (ICC) for his treatment of his people are ideological neocons looking to undermine the regime. They argue that the government is fulfilling its end of the social contract, and while there is no democracy, there is “good governance.” Some further argue that a Western definition of human rights is not everyone’s. The U.S. version of human rights, defined as individual liberty, is not what North Koreans value. Instead, it is freedom from external predation and foreign intervention that is a paramount “human right.” On this score, the regime has done well by its people.

This type of cultural-relativist argument may work for high-minded scholars, but not for most others. The average commonsense person does not demand that every country share the U.S.’s democratic values, but does expect society to allow those who excel to do well, those who need help to receive it, and all to be treated with human dignity. North Korea meets none of these criteria. It is a system that denies its citizens every political, civil, and religious liberty. It severely punishes with physical and mental abuse any perceived violation of laws, without any juridical fairness. And it allows its citizens to starve while the governing elite lives in relative splendor. One would never get this impression in Pyongyang, because Pyongyang city-dwellers are by far the most privileged. Indeed, one cannot live in the capital city without some connection to the party, military, or bureaucracy. Part of this status is determined by family lineage, which means that if your family has party ties, you could do well. It also means that on any day, someone could knock on your door and take you to jail because a distant relative two generations prior was discovered to be a Japanese collaborator. Life looks normal at first glance, but if one stares only a few seconds longer, the cracks become evident. North Korea would like you to believe that their people enjoy all of the creature comforts of modern society. For example, in October 2010, CNN broadcast from Pyongyang a story about how cell phones were prevalent in the North. Second-unit shots showed young, smiling citizens chatting happily away on their cell phones on a street corner. Sure, these phones may be prevalent among the elite and party loyal, but these are not available for purchase by any North Korean citizen (unlike in the South, where smart phones are ubiquitously seen in the hands of grade-schoolers to grandmas); moreover, the service area is limited to local calls only. Instead, most “elite” citizens in Pyongyang use public telephone booths, which became clear to me one afternoon when I saw on several streets scores of people lined up behind orange bubble-like structures. I soon realized that these were city-dwellers lining up to make their one phone call of the day. Visitors to North Korea are sometimes invited to attend Sunday services at a Christian church, which leads them to believe that there is a degree of freedom of religion in the country, while their guides dutifully explain that it is promised in the North Korean constitution. But the reality is that there are three government-controlled churches (two Protestant, one Catholic) in the country for foreigners. The government bans any other form of organized worship as counterrevolutionary and grounds for charges of treason against the state. Buddhism, widespread in Asia, is accepted in the North, within limits, as a philosophy, but not as a religion. The existence of deep underground Christian movements in the North is a telling sign of the absence whatsoever of any freedom to worship anything but Kim Il-sung.

The neat, orderly streets seen by visitors to Pyongyang are that way because there is no traffic. A car is another indicator of privilege and status. Tourists who return from Pyongyang claim that they saw BMWs, Lexuses, and Mercedes-Benzes in the streets, so they conclude the country is doing fine. These cars, of course, don’t belong to average citizens but serve to chauffeur VIPs and dignitaries. As I was driven around in a sedan, I did not see anything but an occasional VIP car or military vehicles. I finally noticed one old beat-up four-door compact. It was orange, rusted, and with no windows. I was told the car was a “taxi.” Official sedans whiz by, which may carry dignitaries or Chinese businessmen, but you don’t see average North Korean moms driving their kids to soccer practice or salarymen commuting to work. On the contrary, everyone walks or rides ancient and dangerously overcrowded 1960s vintage buses. There is also a subway system, which doubles as an underground network of tunnels and bomb shelters. The only times that my car had to stop due to traffic was in the late afternoons, when hundreds of students, still dressed in school uniforms, were marching down the main thoroughfare. Kids who had been playfully walking home from school the previous hour were now expressionless, walking in unison behind a lead sign board that designated their work unit. In school, 33 percent of the curriculum is devoted to the personality cult of Kim. (Typical course titles are the “History of Revolutionary Activities,” “Poetry of Kim Jong-il.”) Children are taught that Kim gave them their clothes, toys, and books, and to love Kim more than they love their parents. They are taught that they can live without their parents but they cannot live without love for and undying loyalty to Kim Il-sung.

Outside of the capital city, the situation deteriorates rapidly. Kaesŏng, the second-largest city, is most well known in the West for the gleaming new joint industrial complex built by the South Koreans. But outside of this structure, the city is in dire straits. Apartment dwellings not only have no heat, they have no windows. Outside the city, farmers use old and diseased oxen to till the land; there is no mechanization visible. The paved roads, despite their infrequent use, are cracked and potholed to the point that they would even make riding a bicycle difficult. The mountains surrounding the area are brown and gray, having long been stripped of all of their trees. Children in grubby clothes can be seen running barefoot among herds of skinny goats. Large, military-green Korean War–era ambulances lumber along, over the bumpy roads. The area hosted bus tours from South Korea from late 2007 to late 2008, and tourists reportedly found it reminiscent of the South in the 1960s.1 Most interesting to me was that no one seemed to be in a hurry. Observed by one Italian chef, who once was asked to make pizzas for the Kim family: “[Y]ou caught sight of people squatting on their heels, their legs folded under them as if doing knee bends. They appeared to be waiting around for something—though it was impossible to tell what this might be, or how long they have been waiting for it, or how long they intended to go on waiting.”2 Asian cities are known for being fast-paced: people rushing to meetings; friends late for a date; car horns honking. None of that exists in North Korea. There is far less to life in this dark kingdom than meets the eye.

Absolute poverty rates in North Korea are over 30 percent of the population. The health-care system, which is said to provide universal coverage, is broken beyond repair. The system services the elite, military, and party members, but no one else. In 2006, the World Health Organization estimated the North Korea government has one of the lowest expenditures on health care in the world, at approximately $1 per person. Medical facilities have power shortages and lack basic supplies. There is no clean water supply and no sterile environments. Hospitals are forced to reuse hypodermic needles. Surgeries are performed without anesthesia. Doctors have long been cut off from payments by the state and therefore barter cigarettes, food, and alcohol from patients for medical treatment. No medicines are available and only the well-heeled can afford to buy medicine on the black market and bring it to the hospital for administering. Tuberculosis, cholera, malaria, typhoid fever, and dengue fever are among the diseases still prevalent in the North.3 This is not a model of “good governance” that absolves the state from charges of human rights abuse.

THE WORST PLACE ON EARTH

The only reason that we cannot claim that North Korea is the worst human rights disaster in the world today is because we are not allowed to see the extent of it. The victims are faceless and nameless, whether they are forced to study Kim Il-sungisms, banished to live in gulags, or tortured and executed for trying to escape the country. No one has a claim to be treated fairly and equally with rights that inhere in one’s dignity as a human being. On the contrary, individualism in North Korea is taught by the state to be a normatively bad trait, because the rights and duties of the citizen are based on the collective. The country maintains the tightest grip on its internal workings, so that the world can never find an individual around whom to organize a cause. Human rights groups, for example, do not have an Aung San Suu Kyi, as in Burma, or a Kim Dae-jung, as in South Korea, that could act as a nameplate for human rights abuses. Without names or faces, the North Korean human rights abuses become an abstract policy problem.

President Bush tried to humanize the issue. On April 28, 2006, he hosted a six-year-old girl named Kim Han-mi in the Oval Office. She is the daughter of a young family that tried to escape from North Korea when the mother was five months pregnant with Han-mi. The family hid in China, where Han-mi was born, and then tried to defect by entering the Japanese consulate in the northeastern Chinese city of Shenyang. Their attempted defection was captured for the world to see as two Chinese guards tackled the mother as she tried to make it through the consulate gates onto foreign diplomatic territory. Pigtailed Han-mi, then four years old, stood at the entrance to the consulate, crying as she watched her mother beaten by the guards. In the pre-brief before the Oval Office meeting, the president stared at the picture that captured this horrific but heroic moment. We explained to him that the girl was now six years old and that she did not speak any English, and that the family may be a little bit in awe of the moment, coming only a few years from the life as defectors to a visit to the White House. (Thanks to the help of human rights advocate Suzanne Scholte, the family made the trip to Washington on very short notice.) President Bush stared pensively at the picture, said nothing, and walked over to the door through which guests enter the Oval Office. The door flung open and Han-mi, sporting a pink dress and pigtails, was the first to enter the room. President Bush flashed a big smile and then swooped up Han-mi in his arms as though she were his own granddaughter. Any nervousness in the room melted away at that moment. With the girl in one arm, he motioned with the other, inviting the parents to sit down and tell the story of how they left the North and made a new life in the South. Han-mi, clearly excited and giggly, sat next to the president in the chair normally reserved for visiting heads of state, and swung her legs as she showed the president a card she made in anticipation of her meeting with him. Like a grandfather, the president stopped his conversation in midstream, pulled out his reading glasses, and then studied the pictures together with Han-mi, complimenting her artistry. When the father finished telling his story of escape from the North, the president asked him what he was doing now. Han-mi’s father responded that he was living in Korea. The president stated that he knew that, but wanted to know what he was doing for a living now. The father apologized for misunderstanding the question and responded, “Oh, I sell cars for Kia Motors,” which the president found wonderful. He then looked at Han-mi’s mother and expressed genuine admiration for her strength and courage to find a better life for their child.

The entire meeting was extraordinary, and one could not help but wonder what was going through the family’s minds. When the press came into the room, President Bush made clear what was on his mind:

I have just had one of the most moving meetings since I’ve been the president here in the Oval Office. . . . I talked to a family, a young North Korean family that escaped the clutches of tyranny in order to live in freedom. This young couple was about to have a child, and the mom was five months pregnant when they crossed the river to get into China. They wandered in China, wondering whether or not their child could grow up and have a decent life. They were deeply concerned about the future of their child. Any mother and father would be concerned about their child. . . . The world requires courage to confront people who do not respect human rights, and it has been my honor to welcome into the Oval Office people of enormous courage. . . . We’re proud you’re here. I assure you that the United States of America strongly respects human rights. We strongly will work for freedom, so that the people of North Korea can raise their children in a world that’s free and hopeful . . .4

On a separate occasion, in June 2005, the president hosted North Korean defector Kang Ch’ŏl-hwan. Kang and his family lived a fairly normal and comfortable life in Pyongyang. During the Japanese occupation, Kang’s family was among the thousands that colonial authorities forced into labor conscription programs in Japan. Kang’s grandfather occupied an important position as a community leader of the ethnic Korean minority living in Japan and, after the end of the war, returned to Pyongyang to settle. One night, guards burst into his house and took him and his family to a political concentration camp on alleged charges against his grandfather pertaining to treasonous activities as a collaborator with the colonial Japanese. In the blink of an eye, the life of this ten-year-old boy was turned upside down. The only belonging he managed to take with him was his fishbowl. He would spend the next ten years of his life in the camp. He was released in 1987 and then defected in 1992 to China, and then South Korea. He wrote of his experiences in a book titled Aquariums of Pyongyang: Ten Years in a North Korean Gulag (2001). Though I had used the book to teach my classes at Georgetown, it was a relatively obscure work, and I never anticipated that the president would read it, until it was recommended to him by Henry Kissinger. (Bush was a voracious reader, contrary to what many may think; studious staff could not keep up with his reading list.) The president became deeply interested in Kang’s story. He knew it so well that he corrected a fact I had flubbed about Kang’s family in a briefing paper. He asked to meet the author. This was the first meeting between a sitting American president and a North Korean defector. It was a private gathering (i.e., not on the official schedule), and we only released a picture to the press, but several accounts of the event have since become available. During the forty-minute visit, the president asked Kang to describe his life imprisoned in a North Korean gulag.5 Kang, who now lives in South Korea and works as a journalist for the major daily newspaper Chosun Ilbo, recounted how even at the age of ten, he was forced to do hard labor. Bush said that the world did not pay enough attention to human rights abuses in the North and that it broke his heart to hear stories of pregnant women and children starving in the country while the military lived in relative splendor. He asked Kang what he thought would be said in North Korea if they knew that he was meeting with the U.S. president, to which Kang responded, “The people in the concentration camps would applaud.” The president then asked Kang to autograph his copy of Aquariums, which he still considers to be one of the most important books he read during his presidency.6

Han-mi’s family, Kang Ch’ŏl-hwan, and other victims of North Korean human rights abuses said afterward that never in their wildest dreams did they ever imagine a journey from the worst place on earth to the White House. They said that only a country like the United States would care about what was happening to the people of North Korea. As I escorted Kang to his meeting, we entered the White House compound through the front entrance to the West Wing. It was an overcast and rainy day, and he paused at the front as the Marine guard opened the door. He glanced at the entrance and naively asked if this was really the White House. I explained that this was the West Wing, where the president worked, and that there was the larger main residence of the White House. He took all of this in with some awe, and said under his breath, “There truly is a God.”

President Bush’s meetings with North Korean defectors were part of a larger effort to reach out to human rights advocates around the world. But in the case of North Korea, these meetings had the effect of attaching names, faces, and inspirational stories to the North Korean human rights issue. The president was never under the impression that a couple of meetings with defectors would somehow magically solve the problems in North Korea. But he used the tallest soapbox in the world to draw global attention to the issue, as well as to humanize it. This was especially important to do with a country like the North, which through opacity tried to dehumanize the issue and make it abstract, distant, and a lower priority than their nuclear weapons programs. The North tried to create a dynamic in which the United States and other members of the Six-Party Talks would be deterred from pressing Pyongyang on human rights because Washington would not want these issues to stand in the way of ongoing nuclear negotiations. But President Bush, to his credit, would not accept such arguments. He was moved by the defector accounts, and in meetings with other world leaders would talk about them, raising the world’s consciousness about the problem.

GULAGS

Life in the political prison camp is worse than death . . . You cannot imagine how harsh the living conditions are. They eat rats, grasses. Their living conditions are indescribable.

—MR. YI K, FORMER PRISON GUARD7

When North Korea collapses, the gulags will be revealed as one of the worst human rights disasters in modern history. Hundreds of thousands of nameless and faceless men, women, and children waste away in the camps. Many have been thrown into the gulags with very little forewarning and without a trial. “Crimes” amounted to no worse than sitting on a picture of Kim Jong-il. Another crime punishable by hard labor was allowing a portrait of the Great Leader to collect dust. Other punishable crimes were humming a South Korean pop song and complaining about the lack of merchandise in the state-run department store. And yet another, punishable by six months in a gulag, was watching a Hong Kong action film on VHS.8 These hardly constitute crimes severe enough to warrant banishment anywhere else in the world. As in any society, there is socially deviant behavior in North Korea that requires law enforcement. But many of these illegal acts are “survival crimes”—a mother pilfering rice from a rations warehouse to feed her starving children, a farmer underreporting production quotas, or a father stealing medicine from a hospital for his sick family.

There are today about five main gulags in North Korea. (There used to be as many as fourteen, but they were consolidated to five in the late 1990s.) Each encampment holds between five thousand and fifty thousand prisoners, depending on its size and scale, the largest of which is estimated to be thirty-one miles long (50 km) and twenty-five miles wide (40 km).9 All but one of these camps are administered by North Korea’s National Security Agency (NSA), the intelligence organization tasked with monitoring of domestic activity, border control and immigration, and international intelligence gathering. Individuals who find themselves in the camps are subject to arbitrary arrest and imprisonment, without trail or any sort of judicial process. They are simply picked up by authorities and brought to the camps, facing torture until they confess to whatever “crime” their captors have accused them of, often regardless of whether or not they even committed it. The camps themselves are surrounded by four-meter-high walls (13 feet), which are topped with barbed and razor wire, or electrical fencing. Intermittent guard towers are staffed by heavily armed guards with orders to shoot-to-kill if anyone tries to escape. Some of the camps are divided into a number of zones, depending on one’s sentence. There are “revolutionizing zones,” where individuals are all serving shorter-than-life sentences and therefore are subject to intensive reeducation in revolutionary doctrine and the thought and scholarship of Kim Il-sung. Then there are the “total control zones,” in which individuals are sentenced to life imprisonment, and are simply kept well-controlled rather than being “reeducated.” These individuals will never breathe the air of freedom (to the extent that that is possible in North Korea), until perhaps they are on the very verge of death, and then the authorities will release them to go off and die elsewhere.

The camps originated after World War II as prisons to hold enemies of the state who were landholders, collaborators, religious leaders, and family members of disloyal Koreans (i.e., those with family members in the South). With the outbreak of the Korean War, the camps were expanded to include those who were seen as collaborators with U.S. and U.N. forces. Anyone seen as a potential political threat to the Kim family was thrown into the camps, whether they were from the party, military, or bureaucracy. Koreans returning from Japan (like Kang Ch’ŏl-hwan’s family) ended up here as well. Students who studied abroad or diplomats who were seen as “polluted” by outside ideas were also fair game. While the camps have existed as long as the current regime in Pyongyang, they took on a new significance in the regime’s repression strategy during the early post–Cold War and famine years. With the loss of its Soviet patron, the decomposition of its economy, and the rapid decline of its food distribution, the North Korean leadership found itself facing theretofore unseen infractions of its systematic, dictatorial control. Unauthorized migration, black market activity, quiet murmurings of discontent, and defection into China all became far more prevalent during these years, and with them, arrests skyrocketed. Today, the prison camp system is a fundamental pillar of North Korea’s repression and political control strategy; an indispensable aspect of the Kims’ totalitarian rule. In total, there are about 200,000 to 300,000 individuals imprisoned today. An estimated 1 million people have died in these North Korean gulags.

The conditions in the gulags are subhuman. Perhaps the best way to convey this is to describe the average day in a North Korean gulag. Generally, inmates are woken up between four and six a.m. to begin their slave-labor. The types of work the prisoners are tasked with vary greatly, but are often hard, physical labor for men and young female prisoners, such as mining, logging, brick-making, and general construction. The work conditions on these sites are incredibly dangerous, with large numbers of work-related deaths and defectors reporting the shockingly high counts of amputees, cripples, hunchbacks, and other generally deformed prisoners as a result of their toil. The older or weaker men and women are forced to carry out light manufacturing jobs, such as sewing clothes and making belts and shoes, and they are driven no less hard than their younger, stronger counterparts. The work is ceaseless and subject to highly strict quotas, which are enforced brutally. Punishments for working too slow or not making a quota range from reductions in already-measly food rations to prolonged solitary confinement to physical abuse to torture. The work is often not interrupted by lunch (because there usually is none), but prisoners, if they are lucky, are allowed to feed on local weeds and grasses as they slave away. Usually, the only justifiable reason to provide prisoners with a break is to gather them to witness a public execution, most often for prisoners who have tried to escape. Execution methods run the gamut, but are similar to those practiced outside prison walls in North Korean society (see below), including hanging, shooting, stoning (which requires prisoner participation), and, in one particularly grotesque case, being dragged behind a moving car.10

Work ends at around six p.m., and the prisoners are sent back to their living quarters to prepare for the meager portions they will receive for dinner. In the North Korean state, prisoners are allocated whatever is left over after the elite, military, loyal class, and Pyongyang and other urban residents are fed, which is essentially nothing. For this reason, on top of their paltry portions of corn, spoonfuls of grain, or a few leaves of cabbage, prisoners are forced to subsist on bugs, beetles, snakes, and, on good days, rats, along with the grasses, barks, and wild foods they collect while working. Kim, a young man who spent four years in a North Korean gulag, describes the food condition:

Malnourishment made life . . . very difficult . . . We were always hungry; and resorted to eating grass in spring. Three or four people died of malnutrition. When someone died, fellow prisoners delayed reporting his death to the authorities so that they could eat his allocated breakfast.11

This combination of strenuous, unrelenting labor and the meager portions of food prisoners subsist on results in what North Korean human rights expert David Hawk calls “permanent situations of deliberately contrived semi-starvation.”12 Defectors attest to losing huge amounts of weight during their stays in the gulags, with one man in his twenties getting down to sixty-six pounds (30 kg) upon release.13 New prisoners, when they first arrive, are reportedly awestruck by the emaciation, disfiguration, and discoloration of the camps’ inhabitants,14 experiencing something reminiscent of what United States and other Allied forces must have felt when they first stumbled upon Nazi concentration camps in Germany and Poland.

After dinner, prisoners are required to carry out a somewhat perverse and Orwellian ritual referred to as “self-criticism.” In these sessions, the prisoners gather around and spend two or so hours confessing the wrongs they committed that day. Even if prisoners don’t feel as though they committed any, they basically have to make them up to avoid being harshly punished for what would be viewed as defiance or dissent. Owning up to these transgressions, real or contrived, results in even more draconian work quotas and longer hours, often for whole work-units under a system of “collective responsibility.” After self-criticism, prisoners are sent off to bed, where they sleep on the hard floor without blankets. In some cases, they are crammed into rooms with eighty or ninety other prisoners, in rooms that are just sixteen by twenty feet (5x6 m, that’s three and a half square feet per prisoner!).15 In the camps, men and women work, sleep, and generally live strictly separately, coming together only for public executions and other “important” collective activities. This is part of an effort to maintain control and prohibit sexual contact, to avoid a new generation of “counterrevolutionaries.” If prisoners survive the night and manage to get some sleep, despite the frostbite they suffer for much of the year, they only get up the next morning to begin the routine once again.

The most well known of the camps is Yodŏk concentration camp. Located in South Hamgyŏng Province about seventy miles (115 km) northeast of Pyongyang, the camp sits in a valley surrounded by four mountains. It is a massive facility and is estimated to be about twenty miles (32 km) long and twenty miles wide. The perimeter is confined by a large brick wall, covered in barbed and electrical wire and surrounded by live minefields to deter escape. Watchtowers, set at one-kilometer intervals (0.6-mi), are equipped with machine guns to prevent any riots (although one was rumored to have occurred in 1974). Anti-aircraft guns ensure against external attacks. The one thousand or so guards that patrol these walls are personally equipped with grenades and fully automatic assault weapons, and are often accompanied by viciously trained guard dogs. Yodŏk alone holds over fifty thousand prisoners, who are zoned into categories as political prisoners, criminals, or descendants of either category. Because the state can imprison you for acts that were committed by your ancestors three generations earlier, no North Korean is safe. There is no judicial process that supports these imprisonments. You could be sent here without warning, and for indefinite time periods.

The camps focus on two tasks: reeducation and forced labor. Prisoners perform slave labor such as working in coal mines (often without tools or safety equipment), building roads and bridges, and producing textiles and other light manufacturing. Some items, including clothing and artificial flowers, are made in these camps for export. The factories in these camps have become a source of hard currency for the regime, so prisoners were often forced to work long hours to make production quotas. In one case, the factory was to meet an order from Japan for handknit sweaters. But once the sweaters were made, complaints ensued that the yarn had become tainted by the unsanitary conditions in the camps. Prisoners were beaten for being dirty, which, of course, was not their choice. In another case, prisoners were required to make doilies for export to Poland. Stitching intricate patterns into the white material was difficult, and prisoners were beaten for making poor-quality products and punished with reduced food rations. Those who did well would be forced to work longer hours in order to meet production quotas. In yet another case, prisoners were forced to make paper flowers for export to France. Each prisoner had a production quota of a thousand flowers per day, which averaged to about sixty flowers per hour or one per minute. If they did not meet this quota, or if they made inferior products, they would be punished.

The guards in the camps are taught to treat the prisoners as subhuman. There are incentives to prevent rioting and to kill any escapees, which sometimes leads the nastiest guards to randomly shoot prisoners in order to win the awards. Mr. An, a former prison guard, claims that “[a]s a prison guard, you couldn’t treat the inmates as human beings. If you did, you’d get punished. If anyone resisted, or tried to run away, we could shoot to kill . . . It was a horrible place, where women and men are killed very cruelly. Some of the methods are too horrible to repeat.”16 Mr. An also confirmed reports that some prison guards force inmates to attempt to climb the fences, just so they can shoot them down for recreation or target practice. Mr. Lee K, another former prison guard, describes the treatment of prisoners in a gulag he worked in:

People in the facility were beaten every day with sticks or with fists. In the evening, they had to make time for an “ideological struggle” . . . This was an official time for the inmates to fight with each other, and the guards indirectly provoke violence. The prisoners had to endure physical punishments . . . There were many different ways of beating. Those who attempted to escape . . . [had] their hands tied behind their back and they were hung on the wall for three to seven days. They were handcuffed and guards would stomp on the handcuffs . . . I witnessed these types of atrocities quite often.17

Aside from the physical abuse many prisoners suffer, female inmates in particular are subject to the pain and humiliation of sexual abuse. Chi, a fifty-four-year-old who was detained after being repatriated from China, describes her experience:

During pretrial detention, I was humiliated, abused. The guards—who were all men—touched my sexual organs, breasts with brooms. All the guards during the pretrial detention period were male. I was alone when I was interrogated. I was beaten for speaking up, as were others.18

Some of the most horrific accounts are of North Korea’s infanticidal policies in the gulags. If a woman is pregnant when she is detained, or becomes pregnant during her internment in the camps, she will be subject to forced abortion or, upon birth, her child will be summarily killed. As a result of severe malnutrition, these women often have highly irregular menstrual cycles, and it is quite common for women in North Korea’s gulag system to not know of their pregnancy until quite late in their term. A female defector who was in a gulag in Ch’ŏngjin City attests to these harsh realities:

[I]f it is found that a woman is pregnant, they administered a medicine to abort. If the woman gave birth to a baby, they covered it with vinyl and placed it facedown and killed it. Seven women gave birth to children in that prison and they killed all of them. The women were in labor in the prison cell and all the female inmates assisted with the birth. On April 1, 2000, I was arrested and I witnessed seven children born during the period of May to June and they were killed.19

When the women are defectors who have been repatriated from China, these policies are often ethnically motivated: to prevent half-Chinese, half-Koreans from “polluting” the North Korean race. When they aren’t, these women are simply told that they are carrying “the children of betrayers” in their wombs, and that this is unacceptable.20 Ch’oe Yong-hwa, a “shy and soft-spoken” twenty-five-year-old woman from North Hamgyŏng Province, ended up in a North Korean prison camp after crossing the border in search of food during the famine. One of her duties during her incarceration was to assist a late-term pregnant female inmate. On one fateful day, she witnessed the prison staff administer a labor-inducing injection, and, upon birth, the infant was suffocated with a wet towel right in front of the mother, who fainted in horror.21 Another defector, a sixty-six-year-old grandmother, had a similar yet even more horrific experience. Being unable to perform hard, physical labor, she was also tasked with taking care of pregnant women in the detention center in Sinŭiju in eastern North Korea. The grandmother witnessed the birth of a child to a twenty-eight-year-old mother, known as Lim. Right after the child was born, a guard grabbed it by its leg and tossed it into a plastic box nearby. Here the child, among others, was simply left to die, as was the standard practice in this particular facility. When the box filled up, it would be taken outside to be buried. A North Korean human rights report describes what the grandmother witnessed next:

Two days later, the premature babies had died but the two full-term baby boys were still alive. Even though their skin had turned yellow and their mouths blue, they still blinked their eyes. The agent came by, and seeing that two of the babies in the box were not dead yet, stabbed them with forceps at a soft spot in their skulls.22

As terrible as the place may be, some who go to Yodŏk can eventually gain release. Located outside of Pyongyang, Sŭnghori is another major concentration camp that has been seen in satellite photos, but because no one is known to have survived it, little information is available about it except that those considered “incorrigibles” are banished there. (Kang Ch’ŏl-hwan’s grandfather was sent here.) Defectors’ accounts suggest it is the most feared concentration camp in North Korea. There are other camps, less severe than Yodŏk. These qualify as prisons or labor camps, but they are distinguished by the existence of a judicial process and fixed-term sentences. But still, the conditions here are so bad that many, even if not banished for life, die from of disease or starvation.

REFOULEMENT

Refoulement is coercive expulsion of political refugees. China has been actively engaged in efforts to sweep up and forcibly repatriate North Korea refugees who enter its territory. As a signatory to the 1951 U.N. Refugee Convention and the 1967 Protocol to that convention, China is obligated to recognize a political refugee who flees his country because of fear of political persecution. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) is the agency that ensures that once an individual is considered a refugee, they are accorded certain rights, resources, and protection. Parties to the convention, including China, have an obligation to the principle of non-refoulement, meaning that “No contracting State shall expel or return (“refouler”) a refugee in any manner whatsoever to the frontiers of territories where his life or freedom would be threatened on account of his race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.”23 China has consistently refused to recognize North Koreans as refugees, and has been forcibly repatriating them, pursuant to a 1986 bilateral agreement with Pyongyang.

The overwhelming majority of North Korean refugees exit through China. Numbers are very hard to come by, since no organization is allowed to conduct a systematic survey. The Chinese official estimate is about 10,000. But activists, press, and other governments put the number as high as 100,000 to 300,000. The DPRK, of course, does not report any migration statistics, and in a 1993 census only stated that “migrant numbers going into and coming out of our country are neglected.”24 A 2008 census made no mention of migration out of the country. The United Nations puts the number at between 30,000 and 50,000. (The population of North Korea is about 22 million.)25 The majority of these migrants are women—as high as 75 to 80 percent. (Male numbers may be underestimated because they are in hiding to avoid deportation from Chinese sweeps.) The majority is also classified as “distress migration”—movements across borders without official documentation out of economic deprivation and chronic food insecurity.26 The movements of people into China started in the mid-1990s and grew steadily, peaking at the end of the decade. There were other routes through Southeast Asia (Vietnam and Thailand) and Mongolia, but only a trickle have succeeded. One famous case involved the Vietnam government turning over 480 North Korean defectors to the South, but this was a onetime event. About 20,000 North Koreans have managed to exit through China, finding permanent settlement in third countries. The overwhelming majority end up in South Korea, where the government provides resettlement assistance that is generous compared with other countries.27 Refugees are accorded South Korean citizenship, and live at a transition facility known as Hanawŏn for three months of education and job training to deal with the challenges of integrating into fast-paced South Korean society.28 According to a 2010 U.S. government report, 1,211 North Koreans have sought asylum in England, Germany, and Canada. The United States, under a new resettlement program, has taken in 96 refugees.29 Only about 14 percent seek to settle in China, because of the fear of refoulement.

Most North Korean defectors come from North Hamgyŏng Province, which is one of the poorest parts of the country. They cross the porous Sino–North Korean border into Jilin Province’s Yangbian autonomous prefecture, populated by 2 million ethnic Koreans.30 Some escapees find work in Jilin, usually menial labor jobs under poor conditions, but still better than what was available in North Korea. Others, mostly women, marry Chinese farmers or laborers as a way to start a new life. There are stories of North Korean families who sell their daughters for cattle on the Chinese side in order to feed themselves as well as give their child a chance at a better life.31 It is estimated that over ten thousand children have been born to Chinese men with North Korean women (who are not given naturalization rights). As one can imagine, this dynamic creates opportunities for human trafficking, which has become a major problem. Women are victims of rape, forced prostitution, and bride-selling, and activists report that as high as 80 to 90 percent of North Korean escapees may be victims of some form of trafficking. (North Korea is rated as a Tier 3 country in the U.S. State Department’s Trafficking in Persons Report—the lowest possible rating.) One such example is of Ms. Ryo, who was in her early twenties when she left North Korea for China in 2001. After she and her uncle crossed the Tumen River, they were abducted and separated by a group of local Korean-Chinese traffickers. Ms. Ryo eventually managed to escape her captors and made her way to a Korean church in Yanji, which was also hiding some sixty North Korean defector children. The church deacon recommended a job for Ms. Ryo, as a housekeeper and Korean teacher for the grandchildren of a local family. But when she showed up for her first day of work, she was subject to a rude awakening. The reality was that she had just been sold by the church deacon for 5,000 renminbi (approximately $600) to the family for their thirty-year-old son. Ms. Ryo describes her experience:

The son had a mental problem . . . He always stayed beside me and the only thing he wanted was for us to always have sex. When I became depressed, he beat me. If I was beaten, I could not walk for a week. He beat me on my face and my body and all my body was bruised black-and-blue.32

After four months of such treatment, Ms. Ryo made her escape in desperation. The son was determined to keep her there, so when he went to work or to sleep, he would hide all of her clothes. But one day, after being “beaten very seriously,” Ms. Ryo snuck out of the house at five a.m., “wearing only [her] underwear and house slippers.” She made her way to another Korean church, this time, thankfully, to be helped on her eventual journey to South Korea.33

Despite international criticism, the Chinese government refuses to consider these escapees as political refugees and instead classifies them as illegal economic migrants that require deportation. Beijing is supposed to allow the UNHCR access to these migrants to determine whether they qualify for refugee status. The UNHCR established an office in China in 1995 in order to handle refugee flows from Vietnam, but the office has been denied access to evaluate North Korean cases. In practice, Beijing does not return every escapee. It is difficult to enforce the 1986 agreement with North Korea religiously. But whenever high-profile cases emerge, or the international community puts pressure on Beijing, the government argues that such acts constitute a violation of its sovereign borders and therefore they are obliged to address illegal immigration decisively. China’s worst nightmare is a flood of millions of North Korean refugees that would add to unemployment problems and potentially destabilize the North. Granting them widescale refugee status could trigger this flood.

From about 2001, China started to crack down on these cases more severely. The police increased the tempo of border patrols, repatriations, and security around foreign diplomatic compounds. The latter was in response to some high-profile attempts by North Koreans to rush through gates of foreign embassies and consulates. The motive was to storm onto a third country’s embassy compound, which constituted sovereign territory, in the hopes that that country would allow the UNHCR access to determine their refugee status. Chinese authorities built green chain-link fences around the perimeter of the U.S. embassy compound in Beijing to prevent defections. Barbed wire was strewn across the tops of the fences and the fences were set a few yards outside the main walls in order to ensure that North Koreans would fall between the newly built fence and the old wall if they tried to jump it. Chinese living in Yanbian are offered rewards of $500 for turning in any North Korean migrants and are fined large sums ($3,600) if they are caught aiding any refugees.34 Periodic sweeps are conducted by police agencies to round up North Koreans (particularly young men) for deportation. As the numbers of defectors increased, China stepped up the sweeps in Jilin Province, and arrested thousands of Korean-Chinese residents of Yanbian who were involved in the refugee business, all in order to create a deterrent against increased flows. According to most studies, these efforts have been effective. The numbers of North Koreans illegally in China have declined, according to one estimate, from 75,000 in 1998 to about 10,000 in 2009.35

The average North Korean is not allowed to travel within the country. Leaving your village requires a special travel pass. Attempting to defect, in this regard, is a major crime that, according to the North Korean penal code, is punishable by a sentence ranging from a minimum of seven years to death, depending on the offense. Once refouled, these individuals are thrown into labor/interrogation prisons along the Sino–North Korean border. Generally, refoulees are asked three questions: (1) “Why did you leave?” (2) “Did you contact any South Koreans?” (3) “Did you go to a church?” Those who answer that they left the country only in search of food are treated marginally more leniently. (Refoulees also can bribe DPRK officials with their earnings in China.) But those who are found to have met South Koreans or missionaries are harshly tortured, as part of “reeducation.” All women discovered to be pregnant are forced to have abortions. Pak Chŏng-il was a twenty-four-year-old male who was forcibly repatriated by the Chinese. He was sent to an underground prison in Ch’ŏngjin, where he was placed in a row of cells holding ten prisoners each. He was not allowed to talk, nor move. He was interrogated while being beaten with chains, belts, and sticks over the course of weeks. The only food he received were kernels of corn and a salty broth. He was forced to clean latrines without any implements.36 As the numbers of forcibly repatriated North Korean men grew since the 1990s, Pyongyang started to hold them separately from the general prison population, for fear of information dissemination of what they might have seen while in China.

Another such example is of a former military radio operator from North Hamgyŏng Province. After his discharge from the military, he became a courier, transporting goods between North Korea and China. But on one unauthorized trip, he was arrested in Yanji and repatriated back to the North to face detention. He was tortured and interrogated for a number of weeks until he was sent to a hard-labor prison camp. During his interrogation he was accused of listening to South Korean radio while in military service, and of wanting to go to South Korea, neither of which was true. At the camp, he toiled away, making bricks and being deprived of the most basic levels of nutrition. He became so emaciated—or so “skin and bones,” as he puts it—that before he was discharged, he was unable to climb a flight of stairs or to carry a few bricks. Because he wasn’t allowed to bathe or change his clothes, he became covered in lice and sores. In the end, the authorities released him just so he wouldn’t die while in their custody.37

These are just a fraction of the horrific human stories. The world’s utter ignorance of the courage and fortitude of these individuals who attempt to escape is tragic. When the Chinese forcibly repatriate, they send the North Koreans back on buses with curtained windows, to ensure anonymity. Of the hundreds of thousands who have tried to escape, similar numbers have been tortured and killed, yet there is not a single identifiable name or face associated with the practice of refoulement that would be known around the world. There are more defector accounts now that reveal the extent of the horror, but their stories circulate among a small expert community and NGO advocates. These groups have organized to put pressure on the Chinese government to allow the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees to have access to escapees to determine whether they can be classified as political asylum–seekers. Yet there is no Nelson Mandela–type figure or a story that captures the public’s imagination and sense of justice.

President Bush tried to draw attention to this problem by issuing a White House statement on refoulement on March 30, 2006. It read as follows:

The United States is gravely concerned about China’s treatment of Kim Chun-Hee [Ch’ŏn-hŭi]. Despite U.S., South Korean, and UNHCR attempts to raise this case with the Chinese, Ms. Kim, an asylum seeker in her thirties, was deported to North Korea after being arrested in December for seeking refuge at two Korean schools in China. We are deeply concerned about Ms. Kim’s well-being. The United States notes China’s obligations as a party to the U.N. Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol, and believes that China must take those obligations seriously. We also call upon the government of China not to return North Korean asylum seekers without allowing UNHCR access to these vulnerable individuals.

Thirty-one years old, Kim Ch’ŏn-hŭi had family members who successfully defected to South Korea. Kim was imprisoned in the North for eight months because of the “disloyalty” of her family. Her five-year-old son died during this time. After her release, she snuck into China in September 2005 and hid for two months. She then tried to enter a Korean school in Dalian, hoping to reunite with her family and win consideration as an asylum-seeker. The school would not accept her, however, and Kim was forced into hiding again, fearing her actions would almost certainly be reported to Chinese authorities, who would seek to forcibly repatriate her. She traveled in secret back to Beijing and the following month tried to defect through another Korean school. This time, Chinese authorities were ready and immediately arrested her. Kim’s family in South Korea contacted politicians and NGOs, making her case known. They feared her refoulement would mean torture and death. U.S. embassy officials in Beijing, ROK officials in Seoul, and U.N. officials all issued démarches asking Beijing not to deport Kim to North Korea and consider her as a potential political asylum-seeker under China’s obligations as a signatory to the U.N. Convention on Refugees. Chinese officials responded only that Kim’s case was under review. A visit to Beijing by the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees António Guterres March 19–23, 2006, provided an opportunity for the Chinese to release Kim, but nothing was forthcoming from Beijing. Then, on March 24, the day after Guterres left, the Chinese informed the U.S. embassy in Beijing that Kim had been deported to North Korea. Chinese handling of this high-profile case enraged South Koreans and American officials, who stated privately that Beijing basically lied to avoid any further pressure. Kim Ch’ŏn-hŭi’s fate after being deported remains unknown. She has been almost certainly imprisoned and tortured for having the courage to seek a better life outside the North.

The White House statement on Kim Ch’ŏn-hŭi was the first of its kind, and yet Kim’s case is typical of thousands who try to escape the North. No other country has singled out one North Korean refugee by name and sought their rescue at the highest levels of government. The statement was released only weeks before a visit by Chinese president Hu Jintao to the White House, and in his meetings with Hu, President Bush specifically raised Kim Ch’ŏn-hŭi’s case. Critics argue that Bush pursued the human rights issues with North Korea as part of a regime-collapse strategy because he despised Kim Jong-il. Or that he was uninterested in negotiations with the North and therefore castigated the regime’s human rights abuses as a way to submarine any potential talks. Nothing could be further from the truth. As his former adviser on Asia Mike Green described, Bush certainly had no love for the North Korean leader, but he was motivated by the sheer horror that such human rights abuses could still take place in the twenty-first century, and that no one stood up for an oppressed population that could not stand up for itself.38 The statement on Kim Ch’ŏn-hŭi was meant to draw the world’s attention to a problem by humanizing and by giving voice to one individual as a representative of the masses of unknown others.

While the people of North Korea have certainly borne the brunt of the regime’s human rights abuses, these atrocities have not necessarily stopped at “water’s edge.” Aside from the acts of terrorism, transnational crime, and arms trafficking outlined in the previous chapters, the DPRK regime is suspected of having abducted over 180,000 citizens of foreign countries since its inception in 1948.39 In the early years, they were mainly well-educated and trained ethnic Koreans from South Korea and Japan, who could help build the North Korean state. But as years progressed—and the North’s intelligence needs for expertise in foreign language and culture increased—the scope of abductions broadened. Foreigners disappeared from places as far-flung as France, Italy, Guinea, Japan, Lebanon, Macau, Malaysia, the Netherlands, Romania, Singapore, and Thailand, only to later turn up in North Korea. Some abductees were quite literally carried off through the use of brute force. Others were lured to the North through promises of employment and a better life. And yet what they all share in common is that once they were in the “Hermit Kingdom,” the vast majority would never set foot outside its borders again, requisitioned to a life of servitude in the name of the Dear Leader and the North Korean state.

You might wonder what sort of society would tolerate the level of inhumane treatment that is seen in North Korea. Certainly, one explanation has to do with the omnipotence of the government that makes social resistance difficult. Yet another has to do with juche ideology, which does not tolerate questioning of the state. But another permissive condition rests in society itself. Korea emerged out of World War II as one of the most class-stratified societies in Asia. Prior to the Japanese occupation, Chosŏn-dynasty Korea was organized around a three-tiered class system with yangban (scholars, government officials, landowners) at the top of the social hierarchy, followed by commoners, and finally, outcasts. This society bestowed rights upon aristocrats and outcasts in completely different ways. Outcasts were treated as subhuman and not accorded the fundamental right to human dignity. Not only was slavery an accepted practice, but hereditary slavery was common in the Korean society. Despite its classless Communist society, North Korea adopted very similar elements of this class stratification. This is known as the “sŏngbun” system. Started around 1946 and becoming fully established by the 1960s, sŏngbun has three dominant categories for society: the loyal, the wavering, and the hostile classes (with fifty-one subcategories). The loyal, or core, class consists of Korea Workers’ Party members, politicians, and military elites. This class enjoys “rights” defined as preference in education, employment, housing, food, and marriage. The wavering class consists of peasant workers. The impure or hostile class consists of pro-Japanese colonial collaborators, criminals, former landowners, businessmen, and families of defectors. Every North Korean has a place in this system that is only nominally determined by one’s own actions. One’s place is also determined by one’s ancestors. Thus, if you were a young North Korean man, who truly believes in the system and works hard, it would not really matter, because your sŏngbun record may show your grandfather to have been a Japanese collaborator, in which case you would be eternally banished to the hostile class. In the Chosŏn dynasty, or in North Korean society today, this three-tiered system essentially means that it was perfectly legitimate to endow those in the lower class with fewer rights than those in the privileged class. Moreover, the subhuman treatment of outcasts is not anathema but expected as just a part of the way things are. The point of this is not to say that North Korean society condones human rights abuses, but that the society created by the government promotes the idea of an underclass that legitimately can be abused. This is part of the “socialist paradise.”

THE GREAT FAMINE

Small children in tattered rags, with wizened, old faces and blotchy skin pick through the mud in search of kernels of corn or seeds of grain, dropped or discarded by those who are buying and selling on the black market. Their bare feet are ashen-gray and caked in dirt from months and even years of having no shoes to wear. Their clothes are filthy, worn, and gray from years of wear-and-tear without having been washed. The contours of their skulls can be seen through their thinning, patchy, discolored hair, a result of chronic protein deficiency and malnutrition. As they stumble about, their infected eyes appear sunken, deep in their sockets, and their cheekbones jut out from their wasted faces in a shocking, almost violent manner. Many have protruding bellies—which, disturbingly, resemble their Dear Leader’s, though theirs are not from an overfeeding of cognac and fine European cheeses but from the edema they suffer, a result of organ failure. These are the kkot chebi (“flower swallows”) of North Korea, the orphaned or abandoned, wandering, homeless children that began to appear in the thousands as the famine emerged in the early nineties.40 To them, Kim Il-sung’s modest, 1960s promise that all North Koreans would “wear silk clothes, eat white rice with meat soup every day, and live in well-heated tile-roofed homes” is, indeed, distant.

A U.S. NGO team went to North Korea in February 2011 to assess food needs in provinces outside of the main city of Pyongyang. They found seven-year-old boys who weighed only seven kilograms (15 lb). They found that 60 percent of the population in these provinces rely on “alternative food”—the grinding up of tree bark and grass in cornmeal to supplement a fifteen-hundred calories daily intake, which is lower than the U.N.-recommended minimal intake. Many suffered from digestive problems because of these alternative foodstuffs. The NGO team interviewed individuals and asked them when was the last time that they had a piece of protein in their diet, defined as a piece of meat, fish, beans, or such. It was telling that many of these individuals knew to the day when they did. One said he had a piece of meat six months earlier—on his birthday. Another said he had one egg a month earlier to celebrate the New Year.41

If you had to choose one key driver for the outflow of North Koreans, it would have to be the food situation. North Koreans started to cross into China from the mid-1990s when the government ration system for distributing food to citizens started to experience shortages. Defector interviews show that only 9 percent of North Korean refugees cite political reasons for leaving the country, while 55 percent say they left for lack of sustenance.42 The great famine that swept across North Korea from 1995 to about 1998 wrought upon the country a degree of havoc and destruction never before seen by its people. Though the numbers are a matter of dispute, the most rigorous estimates put excess mortality as a direct result of the food crisis at between 600,000 and 1,000,000; 3 to 5 percent of the total North Korean population.43 Shortages of food are among the most tragic of humanitarian crises, forcing the most devastating of situations upon its sufferers. Having to decide how to allocate food within a family, abandoning one’s own children, selling one’s body for a meal or two, taking one’s own life, and watching loved ones slowly waste away to the ravages of hunger and disease are all experiences that were widely felt by the North Korean population during the famine. It unleashed the type of hunger and deprivation that turns brother against brother, even mother against child.

For as long as human rights have existed, the “right to food” has been an inseparable part of the concept. Article 25 of the 1948 United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that all have the “right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care.”44 Article 11 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESR), to which North Korea acceded in 1981, states that “States Parties to the present Covenant recognize the right of everyone to an adequate standard of living for himself and his family, including adequate food, clothing, and housing,” and recognizes “the fundamental right of everyone to be free from hunger.”45 At the 1996 World Food Summit in the midst of the famine, representatives from 185 countries, including the DPRK, reaffirmed the “right of everyone to have access to safe and nutritious food, consistent with the right to adequate food and the fundamental right of everyone to be free of hunger.”46 And so, when a state proves unwilling, or even unable to guarantee basic nutritional sustenance for the entirety of its population, it commits a grave violation of human rights, as North Korea has done for so many years. The right to food is not merely a tangential humanitarian concern, but is itself a fundamental human right.

It must be stated that a centrally controlled, socialist, totalitarian state suffering a food crisis of this magnitude is certainly no anomaly. Political economist Nick Eberstadt even goes as far as to say that “episodic but severe food shortages are, in fact, a characteristic and arguably predictable consequence of the twentieth-century Marxist-Leninist state’s approach to economic management and economic development.”47 The Soviet Union suffered tremendous mortality as a result of famine in 1921–1922 (9 million dead) and in 1946–1947 (2 million). The then-Soviet-controlled Ukraine suffered a famine of its own in 1932–1934, leading to the deaths of over 7 million Ukrainians. The Great Leap Forward in the People’s Republic of China from 1958 to 1961 resulted in an astounding 33 million dead. Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge suffered a famine from 1977 to 1979, leading to the deaths of as many as 2 million Cambodian men, women, and children. During the leadership of the Communist military junta known as the Derg, in Ethiopia, the population suffered famine from 1983 to 1985, leading to as many as 1 million deaths.48 And Communist-controlled Mongolia and North Vietnam also experienced serious food shortages during the first ten years of their rule.49 These horrific events add credence to Nobel Prize–winning economist Amartya Sen’s famous claim that “no famine has ever taken place in the history of the world in a functioning democracy.”50

It is also important to recognize the qualitative difference between the famine in North Korea and past famines in places such as Somalia. Somalia suffered famine for a period from 1991 to 1993, leading to the deaths of as many as half a million of its people. This famine was a result of a combination of drought, conflict, and a central government in the capital Mogadishu, which literally controlled only a few city blocks. One can certainly hold the Somali government liable for its lack of capacity, yet in North Korea, the leadership had much higher levels of state capacity and managed to strictly control the bulk of its population. And the regime was certainly aware of the crisis early on, as indicated by Kim Jong-il’s 1996 statement that “the most urgent issue to be solved at present is the grain problem . . . the food problem is creating a state of anarchy.”51 Beyond that, rather than simply having its hands tied by its incompetence, the regime in Pyongyang continued to spend vast sums of money on luxury goods, sophisticated defense technology, and allocated food rations away from North Korean civilians to its military personnel. Throughout the early 1990s, as the famine was heating up, North Korea is estimated to have spent 25 percent of its GDP on its military budget.52 And in 1999, as the country was receiving massive amounts of food aid at the tail end of the famine’s devastation, the government purchased forty MiG-21 fighter aircraft and eight military helicopters from Kazakhstan.53 Further, once food aid started flowing in, in 1996, the regime began to simultaneously reduce its commercial food imports, essentially using the aid as a substitute rather than a supplement, and perpetuating the famine in the process.54

THE CAUSES

The causes of the North Korean famine are many, but they centrally revolve around misguided government policy in Pyongyang. Although North Korea had periodic food shortages in the mid-1940s, 1950s, and early 1970s, the real problems began with the collapse of the Soviet Union at the end of the Cold War. Beginning in 1987, with their own economy in disarray, the Soviets began to cut all forms of aid, trade, and investment in the DPRK, causing a tectonic shift in the North’s international economic position. By 1993, imports from Russia were a mere 10 percent of the levels from 1987 to 1990,55 and would eventually peter out to insignificance. The steep decline in the fuel, fertilizer, and pesticide/herbicide imports upon which North Korea so critically depended had immediate and adverse impacts on the state’s ability to maintain sufficient levels of agricultural production. What followed was the gradual decomposition of the state-run public distribution system, and with it, disaster.

The public distribution system was the sole means of obtaining food for 60 to 70 percent of the North Korean population since the early 1950s.56 The PDS aggregated harvested crops from collective farms, distributed food among the urban population, and allocated volumes based on a complex and multilayered system of entitlements. North Korean economics experts Stephan Haggard and Marcus Noland point out that the most recent forms of classification in the DPRK consist of fifty-one distinct categories of person, each with its own certain right to entitlements based on age, occupation, family background, regime loyalty, and the like.57 Nutritional experts generally believe that an adult needs, at the very least, about five hundred grams (1.1 pounds) of food per day to maintain a normal level of health. In theory, North Korean Special Forces and heavy laborers are entitled to eight hundred grams (1.76 pounds) of food per day, but the members of Special Forces get a 7:3 rice-to-corn ratio, whereas the laborers only get 6:4. On the other end of the scale are preschool students and the aged and disabled, who are entitled to three hundred grams (0.66 pounds) of food daily.58 The South Korean Ministry of Unification estimates that the prisoners in North Korea’s gulags receive, on average, the ration of a child between two and four years old, a mere two hundred grams (0.44 pounds).59 All of these entitlements are subject to modification, depending on whether one is considered a member of the “core,” “wavering,” or “hostile” class, which itself is determined by one’s family background and perceived allegiance to the regime. The North Korean leadership has and continues to use the allocation of food and access to health care and educational opportunities to confer benefits for loyalty or to punish dissent, making it a decisive tool of political control for the political elites in Pyongyang.

The PDS started to show mild signs of breakdown fairly early on. In the 1960s, for instance, white-collar workers were supposedly entitled to and received 700 grams (1.54 pounds) of food per day through the system. But this number had, in actuality, gradually decreased to 608 grams (1.34 pounds) by 1973 and to 547 grams (1.2 pounds) by 1987.60 In 1992, the government initiated a “Let’s Eat Two Meals per Day” campaign to help deal with the food shortages that were crippling the PDS. Private markets sprang up all over the country. Hordes of the kkot chebi described above began to swarm these markets and urban centers in search of food. The numbers of defectors swimming across the Yalu and Tumen Rivers into China began to skyrocket, and with them, the number of executions and political prisoners. Food riots are even said to have broken out in North and South Hamgyŏng Provinces,61 an unheard-of level of disorder in the ultra-orderly totalitarian state. Villages were abandoned wholesale, as residents emigrated en masse after food stocks and sources were completely exhausted, leaving only the dead behind. At least some of these migrants flooded into Pyongyang in search of any form of nutrition, eventually leading the regime to forcibly deport them from the capital, as it was dealing with its own shortages.62 In May of 1994, as the world was concerned with the first nuclear crisis with the North, Chinese sources were referring to what was occurring as the “worst food crisis in history”63 in the DPRK. By 1997, the regime’s heralded control tool, the PDS, was estimated to be supplying just 6 percent of the population, and by 1998 it wasn’t supplying anyone for large portions of the year.64

The steady decline of the PDS was compounded by a series of catastrophic natural disasters that befell the North. In 1995 and 1996, there was flooding on a biblical scale. On a particular day in North Hwanghae Province, 877 mm (34.5 inches) of precipitation was recorded in just seven hours,65 more than the state of Vermont’s annual average (855.7 mm [33.7 inches]). This flooding was followed by periods of severe drought in 1996 and 1997, and a typhoon in August 1997. The flooding, drought, and typhoon not only wiped out existing crops but also destroyed an estimated 85 percent of the country’s hydroelectric capacity and ravaged its coal-power capabilities.66 This severely hampered the state’s ability to generate electricity, and therefore the few collective farms that survived the natural disasters had little ability to carry on large-scale agriculture. None of this would have been disastrous had the regime in Pyongyang maintained adequate emergency stocks of food, but the inefficient nature of the PDS and its multiyear decline rendered these reserves grossly inadequate.

Finally, there were simple issues of geography. North Korea is relatively far north, running from the thirty-eighth parallel up to the forty-third, which accounts for its harsh winters and a relatively short growing season. It is also not abundant in highly arable land, with only approximately 20 percent of the territory being cultivatable.67 As a result, historically the northern part of the Korean Peninsula was the industrial rust-belt, and the south, the agrarian heartland. Yet wholly contradictory to these geographic realities, soon after its foundation, the DPRK implemented its juche ideology, which emphasized self-sufficiency in all areas of life, including in agriculture and food production. Given the North’s high population-density ratio to its allotment of arable land and its relatively short growing season, for much of its history the regime feverishly tried to keep up with demand by overusing fertilizers and chemicals, and by continuous cropping, a practice that leads to soil erosion over time. The North is also highly mountainous compared to its southern counterpart, with this type of topography covering approximately 80 percent of the territory.68 Because of its desire for self-sufficiency and the need to keep up with demand, the regime’s solution was to deforest and cultivate hillsides, exacerbating the soil’s erosion.69 Their overreliance on fertilizers and other chemicals also proved disastrous, for when they lost their Soviet patron in the late 1980s, they lost the vast majority of these crucial inputs. Again, these geographic realities wouldn’t be a problem if the North simply had had an open economy, traded in the international market, and imported the bulk of its food. But its stubborn faith in a system of central economic control and complete self-reliance essentially doomed it from the start.

LIFE WITHOUT FOOD

And so, a combination of misguided government policy, massive geopolitical shifts, natural disasters, and unfavorable geography led to the eventual loss of as many as 1 million North Korean lives. The extent and the scale of the deaths was truly harrowing, as defector Ms. Kim attests to:

I personally know about fifteen people who died of hunger. In the case of an acquaintance of mine, her entire family died. There were so many deaths; we got used to seeing dead bodies everywhere—at train stations, on the streets.70

Because of the aforementioned social stratification and harsh central control, certain areas of the country and particular classes and occupations experienced more death than others. In a 1998 survey of almost seventeen hundred refugees, 85 percent of respondents said that North and South Hamgyŏng Provinces were the hardest hit, and 88.7 percent believed urban areas to be more severely affected than rural ones.71 The most likely to suffer under the famine were those who were jobless, or those in marginal jobs such as construction. But by far the most vulnerable were infants, children, and the elderly. In five short years, between 1993 and 1997, the infant mortality rate of North Korea increased by over 25 percent, from forty-five per thousand to fifty-eight per thousand.72 A 1998 World Food Programme survey covering eighteen hundred children aged six months to seven years found the prevalence of stunted growth as a result of malnutrition to be over 60 percent.73

But while these certain groups and areas were hardest hit, no one except the Kims and their inner circle seemed to be fully protected from the ravages of the famine. For instance, Mr. Lim, a soldier from Hwanghae Province, describes how many men in his unit died as a result of malnutrition:

You know they were hungry. And then you don’t see them for a while. Eventually, someone finds them dead in their own home. That was quite typical. And then there were those who died on the street, after wandering around to find food. There were so many dead people that the authorities often couldn’t find surviving families, so they would bury them in fives or tens in hills, without even coffins.74

When the worst of the famine set in, the tyranny of hunger refused to discriminate, despite the regime’s complex classification schemes. Kim Yŏng, a defector who was in a North Korean prison camp from 1996 to 1998, summed up the general misery, lamenting, “There are so many miserable stories. People pick undigested beans out of the dung of oxen to eat. They compete to take the clothes off of dead bodies to wear. It is not a human world.”75

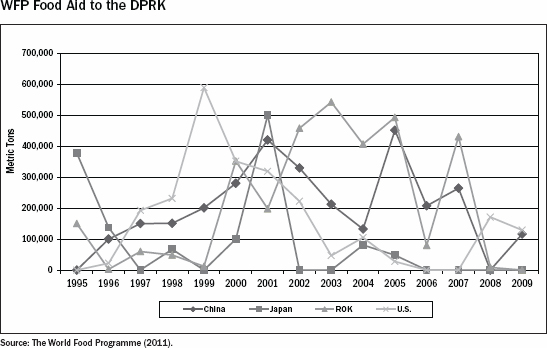

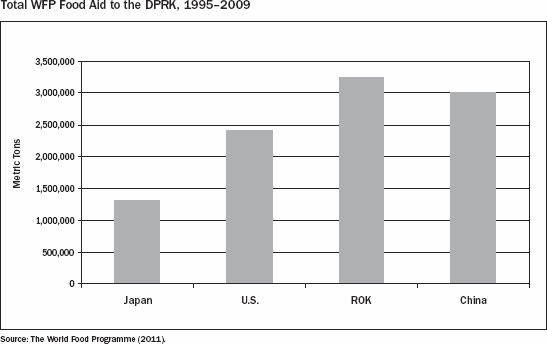

It must be made clear though that it is not hunger per se that leads to the majority of the death in famine situations. Rather it is the plethora of diseases, some infectious, that emerge among populations with malnutrition-induced, weakened immune systems, and in this regard North Korea was no exception. Tuberculosis, an acute respiratory illness, was rife among the North Korean population, and anemia, a common blood-oxygen-level disorder, was also widespread. Cholera, an intestinal infection often carried by dirty water, was brought on and exacerbated by the repeated flooding in the country, causing the deaths of many malnourished soldiers and civilians.76 And malaria, a parasitic disease, was said to have increased dramatically over the course of the famine.77 Added to this list are the simple health issues that often end up proving deadly, like prolonged diarrhea among children and eye infections leading to blindness. Further, there are the longer-term health implications of chronic malnutrition, such as major digestive dysfunction, heart failure, declines in brain function, and trauma-induced long-term psychological damage. There are also increased miscarriages and premature births, elevated levels of stillbirths, and reduced conception due to malnutrition, which carry significant demographic implications.