Dinner at the 21 club in manhattan is an experience. however, it is even more extraordinary when it is with the North Koreans. We pulled up to the New York City landmark on East 52nd Street for dinner after an afternoon of quiet bilateral talks with the visiting North Korean delegation under the auspices of the National Committee on American Foreign Policy (NCAFP). Donald Zagoria, a good friend and a professor at Hunter College, who wrote the seminal book on the Sino-Soviet split, ran these NCAFP track II dialogues, which brought together scholars and practitioners to discuss U.S.–East Asia relations, but in this instance, in April 2005, also provided an unofficial venue in which we could talk with the DPRK about how to put negotiations back on track.1 Pyongyang had boycotted the Six-Party Talks since June 2004, claiming that then–secretary of state Condoleezza Rice’s designation of it as an “outpost of tyranny” in her Senate confirmation testimony confirmed U.S. hostile intent in the second term of the Bush administration. Our team—Joe DeTrani, then–special envoy for North Korea and a former experienced CIA veteran, and Jim Foster, director of the State Department’s Korea Office, was to use the NCAFP meeting as an opportunity to chart a path back to the Six-Party Talks. During the lunch break, we retired to an adjacent room from the conference. It was the first direct talks between the two sides after Bush’s reelection. The North Koreans complained about Rice’s statement and demanded an apology. We said that we could not give one. They maintained that without an apology, there was no chance of negotiations. They then asked what the secretary meant by her “outpost of tyranny” statement. I responded, “What do you think she meant?” This repartee continued throughout the two-hour meeting until we said that the DPRK delegation would not have been given visas by our State Department and would not be in New York if the Bush administration were not serious about negotiations. They then asked, almost rhetorically, “Can we take Rice’s remarks to be her own opinion?” DeTrani, a Brooklyn Italian, responded that remarks given by an administration official in testimony to the U.S. Senate represented official policy, but that they could interpret them however the hell they wanted, as far as he was concerned. At that point, as if on cue, the new assistant secretary of state, Chris Hill, called DeTrani on his cell phone to ask how things were going. DeTrani handed the phone over to the North Korean delegate, who was visibly pleased at Hill’s expressed commitment to restarting negotiations on denuclearization.

We retired for the dinner that evening, at which Zagoria brought together some foreign policy luminaries, including a former world-famous secretary of state, to try to convince the North that nuclear weapons were not the right path. The Japanese and Korean press, having gotten wind of “official” U.S.-DPRK talks taking place in New York, swarmed the 21 Club entrance like paparazzi after Lady Gaga. As we disembarked our cab on the rainy street, we were accosted by a phalanx of reporters creating a scene of flashing cameras and car horns blaring as curious passersby wondered who these unrecognizable gentlemen might be. We fought our way through the press scrum down the wet steps of the New York brownstone into the club, where we were escorted to a VIP room. There, the North Koreans sat opposite a dining table’s worth of Who’s Who of U.S. foreign policy stars who had worked on issues ranging from Ireland to China. The DPRK delegation was clearly pleased at the audience they were given and treatment befitting Wall Street CEOs. After the afternoon’s hopeful negotiations put things back on track, I found myself suddenly despondent, not over the food or company, but over the entire evening’s scene. I looked at our surroundings in this elite New York City establishment, paparazzi standing in the rain outside, and thought to myself, “Would the North Koreans ever see the inside of the 21 Club if they did not have nuclear weapons? Would they be sharing toasts with these icons of U.S. foreign policy if they were just from a poor country without nukes? Jeez, why would they ever give up their nuclear weapons?”

HOW DID WE get to this point? Why have the North Koreans been able to get away with the international relations equivalent of murder? Studying North Korea’s odyssey as both a policymaker in the U.S. government and academic, I find myself still marveling at how this state has managed to survive. Despite making all of the wrong economic decisions throughout its history, the country eked out an existence. Despite propagating an ideology that provides luxury to the Kim family and very little to the rest of the population, the people, even defectors, retain affection for the dynasty. Despite engaging in the most threatening behavior in East Asia, including military attacks and building nuclear weapons, the regime has yet to suffer punishment in the form of retaliation or a preemptive strike. In each case, the regime has survived, though not through extraordinarily shrewd statecraft or policymaking. On the contrary, historians will remember North Korea for all the ways not to run a country. But it has survived through extraordinary circumstances of history and geopolitics. Fate gave North Korea a border with China, and this border has, over the years, compelled Beijing to backstop the regime to keep its northeast flank stable. This border has also prevented other powers, like the United States and South Korea, from seriously contemplating military punishment of the regime to liberate its people. The last time the United States tried this in 1950, it led to a wider war with China, which no one wants today. Kim Il-sung’s sudden death in July 1994 and Kim Jong-il’s death in December 2011 did not provide opportunities to overthrow the system at a vulnerable moment, because the norms of sovereignty just don’t allow outsiders to do this. (The notable and controversial exception of Iraq proves the norm’s validity.) Finally, the world has watched North Korea slowly build a ballistic missile and nuclear weapons program over the past twenty-five years in no small part because the world can’t be bothered with North Korea. The weapons are undeniably dangerous to the United States and its allies, but ultimately, an Israeli-type attack—whether in 1981 in Iraq or in 2007 in Al-Kibar, Syria—is not likely in North Korea because the issue simply does not rank highly enough in terms of U.S. priorities. It is sad to say, but for the American people (and, therefore, the U.S. government), the North Korea issue is not like the Middle East or Afghanistan. It requires attention but not of the highest order like rooting out Al Qaeda’s leaders or tending to the Arab-Israeli conflict. Thus, when North Korea threatens, the pat response is to “park” the issue: avoid a military conflagration (because it is just not worth fighting over) by diverting attention to other important issues, and put it back on a negotiation track to prevent another crisis. This “relative crisis indifference” syndrome in Washington has saved North Korea countless times and given it benefits through negotiation rather than punishment for its misdeeds. North Korea’s survival is not due to its exceptionally skilled government. A concatenation of forces—sovereignty (protection from external intervention), a border with China, and relative U.S. indifference—has made North Korea’s survival an accident of history. It is, truly, the impossible nation-state.

NORTH KOREA’S ARAB SPRING?

For how long can this continue? As I stated at the outset of this book, not for very much longer. I believe the next U.S. president (and South Korean president) will have to deal with a major crisis of the state in North Korea, and potentially unification, before he or she leaves office. Just as a confluence of circumstances has enabled the regime to survive against all odds, a new and unique constellation of forces—Kim Jong-il’s death, his young son’s inexperience, the society’s growing marketization, and cracks in the information vacuum—is emerging that bodes ill for the regime. Skeptics would disparage such an assessment. In May 2010, I participated in a conference (unclassified) hosted by the intelligence community, focused on this very question, and longtime analysts of North Korea predicted no change to the DPRK’s stability. They pointed to past history as their evidence. North Korea was abandoned by its patrons at the end of the Cold War, suffered a famine, and then saw its leader Kim Il-sung’s death, and yet the regime remained intact. Control today in Pyongyang remains intact, it was argued, and regime succession to Kim Jong-un is well established. The final verdict was that revolution in North Korea was unlikely. This is true, but the phenomenal events that have taken place in the Middle East and North Africa have shown us two things. First, in spite of all the reasons for thinking that things won’t change, they could, and quite suddenly. And second, the mere existence of variables that could spell the collapse of an authoritarian regime tells us nothing about when or if that collapse could happen. Among the ruins of collapsed dictatorships in Libya, Egypt, and Tunisia, experts have picked out causes that have long been in existence, yet they cannot explain why they led to collapse in 2011 as opposed to decades earlier. Dictators who have fallen in the tumultuous protests of the Arab Spring—Saleh of Yemen, Ben Ali of Tunisia, Mubarak of Egypt, and Qaddafi of Libya—had each been in power longer than Kim Jong-il in North Korea. Can we simply assume that events in the Middle East have no bearing on the North Korean regime?

THE CAUSES2

Answering this question necessitates getting down to the root causes of popular revolutions and uprisings. The events that took place and continue to take place across the Middle East and North Africa since late 2010 are historic in their scope and scale. The dramatic self-immolation of Mohamed Bouazizi, a frustrated and humiliated twenty-six-year-old vegetable vendor in Tunisia, set off the greatest movements for political change the region has seen since the fall of the Ottoman Empire some ninety years earlier. In the months that followed, men, women, and children—individuals, young and old—rose up to challenge their governments in the face of violence and even death. From Tunisia it spread to Algeria. And then to Libya. And from Libya, on to Egypt. Within a few months, nearly every single state in the region, in one way or another, had to deal with popular uprisings of some sort. The reverberations didn’t end at the edge of the desert. The Chinese government reportedly firewalled their Internet against searches of “Egypt,” “Jasmine Revolution,” and “Arab Spring.” And in North Korea, orders were given to ban all public gatherings, and in July 2011 the government decreed the shutdown of all universities to put students under the thumb of the regime’s work program.

On the surface, Bouazizi’s dramatic suicide was the immediate cause, but there were obviously much larger forces at work that turned this single event into a mass movement. The causes for the Arab Spring can be divided five ways: modernization theories, development-gap theories, demographic theories, contagion theories, and regime-type theories. One collection of possible explanations falls under what political scientists refer to as the “modernization theory.”3 What this body of work argues is that the process of human development brought about by socioeconomic modernization in society leads to increased levels of desire for, and eventual sustenance of, democratic forms of government. What is generally seen across societies, whether they are Arab, Asian, or American, is that the process of modernization brings with it similar traits. Things such as urbanization, the rise of literacy rates and education levels, civic organizations, a more secular public sphere, market-type economies, the emergence of a property-owning middle class, and the temperance of class divisions, tend to accompany societal modernization. With these developments, individuals tend to think less about where they are getting their next meal and more about how their government is performing. Put simply, when wealth increases and individuals begin to develop, they are implicitly given a stake in the system. Once citizens get a taste of a better life, their expectations and demands grow exponentially faster. Thus, it was not dire poverty and other such grievances that set the Arab Spring in motion. Rather, it was, at least in part, minimal levels of individual development.4

Modernization is measured by looking at levels of wealth in societies. Societies with higher levels of individual wealth, unless they are primarily oil-exporting petro-states, will be more prone to movements toward democracy. It is not the wealth per se that will lead to mass movements, but the factors listed above, such as health and education, which tend to accompany this wealth.

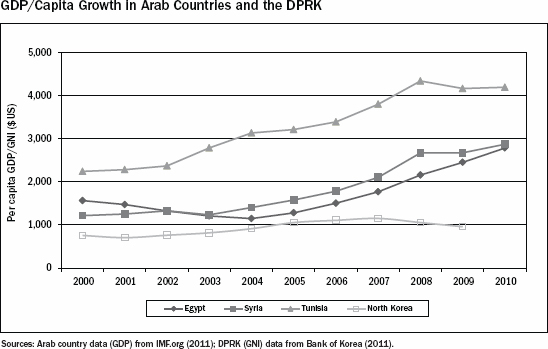

Tunisia, for example, is, in fact, a surprisingly modern society, with the average Tunisian making nearly $3,800 in 2010. While this may not seem like a lot to developed-world audiences, it is significantly more money than was made by the average Chinese, Indian, or Indonesian, as well as by people in eighty or so other countries in the world. The U.N. Human Development Index, which combines measures of health, education, and income, puts Tunisia in the 68th percentile in the world, a full ten points above the regional average. Egypt displayed similar characteristics, though less starkly than Tunisia. In Egypt, the average individual made $2,270 in 2010, and while that doesn’t put it in the class of Luxemborg ($105,044), it is also not with Burundi ($160). With regards to its human development, Egypt sits at the 62nd percentile, which is still well above the regional average. In Libya, too, we see a relatively modern society. Its per capita GDP of $9,714 is artificially inflated by the fact that the country derives nearly 60 percent of its GDP in oil exports, but a fair amount of this does seem to trickle downward. Its human development rating is in the 75th percentile, significantly higher than Tunisia, Egypt, and most other regional states, and its life expectancy is seventy-five years. Syrian society exhibits similar tendencies, with a per capita level of wealth at about $2,500 and a human development ranking at just below the 60th percentile. But in some of the cases, modernization theory seems to reach its limits. For instance, in 2010, the average Yemeni made just over $1,000, and Yemen’s Human Development Index rating is at about the 40th percentile, nearly twenty points below the regional average.5 So, it seems, there must be more at play here.

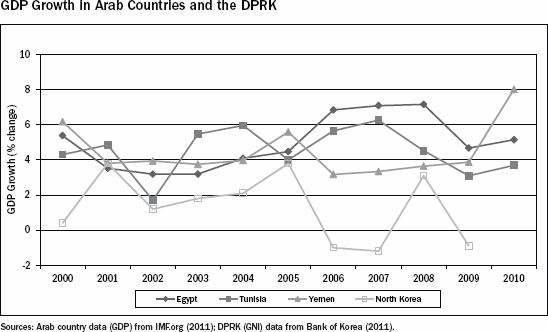

Rather than focusing on the individual, some look at broad socioeconomic development as a possible catalyst of unrest.6 If growth in the overall economy occurs in a rapid fashion, it often outpaces the political institutions that make up the society and can lead to instability. This phenomenon is akin to what the late Harvard political scientist Samuel Huntington referred to as a “development gap”: people’s aspirations increase at a faster rate than the government is able to meet them.7 Their “wants” begin to form faster than they can be satisfied. There is some evidence of this in a number of the Arab Spring countries, as the past decade has been marked by steady economic growth but stagnant authoritarianism. In Libya, for instance, the economy has grown at an average of just over 4 percent per year, peaking at 13 percent in 2003, with only modest increases in its population. Tunisia, too, has grown at an average of 4.5 percent per year over the past ten years, adding only about 10 percent to its total population during that time. Yemen as well, believe it or not, has averaged just under 4.5 percent growth per year since 2000, but has seen more substantial population growth numbers. Syria and Egypt also have had growth rates averaging consistently above 4 percent, but their more-rapid population growth has taken some of the force from this increased economic power.8 GDP per capita growth mirrors these developments. Since the year 2000, Egypt experienced a 31 percent increase in its real GDP per capita.9 Over the same period, Libya’s was just under 20 percent and Syria’s just shy of 23 percent. Tunisia, over the past decade, has seen its GDP per capita increase by a full 41 percent, with Yemen trailing quite well behind the rest with just 12 percent growth.10 And yet, while there may be some variation in growth levels among these countries, what they all share in common is political stagnation at the highest levels, something political scientists refer to as “authoritarian entrenchment.”11 Saleh of Yemen has been in power since 1990, Ben Ali of Tunisia since 1987, Mubarak of Egypt since 1981, and Qaddafi since 1979. Bashar al-Assad in Syria took power in 2000, but he inherited the throne from his father, Hafez, who ruled the country for twenty-nine years. In 2010, these five states had either a six or a seven out of seven (seven is the least freedom; one is the most), according to Freedom House’s Freedom in the World index, and were all labeled “not free.”12 The steady growth of their economies during the 2000s essentially meant that the people began to outgrow their governments.

Another group of theories looks at the demographic makeup of a society.13 The younger a population is and the less it is employed, the higher are the chances for civil unrest. It is easy to imagine how hundreds of thousands, or even millions of underemployed, disaffected youth can lead to trouble for a government in relatively short order. And in many cases this is what was seen in the Arab Spring, with some referring to what happened in the region as a “youthquake.”14 Yemen is, perhaps, the quintessential example of this theory at work. Its median age is just 18 years old,15 and its unemployment rate, the last time it was officially measured (which was 2003), was 35 percent. Libya also seems to fit the bill. Half of the population in the country is under 24.5 years, with an unemployment rate of a whopping 30 percent. Tunisia, too, had a fairly high unemployment rate of 14 percent in 2010, and a median age of 30 years; still significantly lower than developed countries like the United States (37 years), Canada (41 years), and Japan (44 years). Egypt, as well, has a fairly young population; half being under 24.3 years. Yet its unemployment rate is surprisingly low, at just under 10 percent. And Syria, which also has a relatively young population, has a median age of 21.9 years, but a surprisingly low unemployment rate of its own, floating just over 8 percent.16 And so, the sort of hit-and-miss nature of the “youthquake” hypothesis points to the possibility of still more factors making their presence felt.

Getting beyond the internal, structural factors in these societies, there are powerful arguments for external factors as having contributed to the Middle East and North African uprisings. One such example is what commentators have referred to as “contagion” effects. A man in Egypt was said to have set himself alight after the inspiration of his Tunisian comrade. Then Facebook groups started popping up all over the region and the world, claiming “We are all Egyptians now!” The inspiration effect of one country’s struggle on another is unquestionable. But how does this happen? In the modern era, the rise of rapid communications technology and the twenty-four-hour news cycle ensures that in all but the most repressive regimes, information is ubiquitous. Although the press in individual countries may be harshly repressed, social media such as Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and SMS ensures that dictators can no longer plug every leak. In Tunisia, for instance, 91.8 percent of its 10.6 million people have mobile phones, and 33 percent have Internet access, the highest in North Africa. Similarly, in Egypt, 64.7 percent have cell phones, and about 25 percent are Internet users. In Libya, 76 percent have cell phones, and in Yemen, 34 percent. In Syria, too, 37 percent have mobile phones and just under 20 percent use the Internet regularly.17 Though some of these numbers may seem small compared to the developed West, they were certainly enough for all of us to see personal footage from inside these movements on the news on a nightly basis. The relatively high literacy rates in these countries, moreover, act as a force multiplier for these types of media. In Libya, it is 89 percent, in Syria 84, in Tunisia 78, in Egypt 66, and even in Yemen, 62. This means that the potential for spread is all the greater. While a literacy rate of 62 percent may not seem all that impressive, it must be remembered that a number of sub-Saharan African states have rates that are less than half that.18 Through these media, individuals can share information, organize protests, and post pictures and videos online for all to see. But perhaps more important than these new, Internet- and handheld-based social media, is the good old television. In the Arab Spring, this is what some commentators referred to as the “Al Jazeera effect.”19 Libyans saw coverage of the Tunisian revolt on Al Jazeera, which, in part, encouraged them to rise up. Followed similarly by Egypt, then by Yemen, and so on. And the relative ubiquity of televisions in society facilitated this effect. In Yemen, for instance, there are at least 34 televisions for every 100 inhabitants. In Egypt, there are 24. Syria boasts 19, and Libya 14.20 Again, while these numbers may not seem all that impressive for the average American (where there are 74 TVs for every 100 people), it is worth remembering that in the world’s most impoverished societies, such as Eritrea (0.02/100), Chad (0.1/100), and Tanzania (0.28/100), television is basically nonexistent for the vast majority of the population.21 And rather than literacy, in the case of the Al Jazeera effect, the force multiplier was the fact that Arabic (the language of Al Jazeera) is widely spoken in at least twenty-eight countries worldwide, basically all situated in the Middle East and North Africa. In this way, protest among Arab states was “contagious,” in that it went from one to the other to the other, until even the Chinese and the North Koreans began to get nervous.

A final important causal factor has to do with the type of regime in charge of the country.22 It can be argued that regime types that allow some freedoms in the name of economic growth or as a steam valve for popular dissatisfaction are more liable to face upheaval among their people. It is this type of “soft authoritarianism” that opens up the classic dictator’s dilemma: a snowball effect where leaders may allow some freedoms to keep growth rates up, but in doing so they sow the seeds of their own destruction as they lose control of the population. In Tunisia, this was most certainly the case. According to the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) Democracy Index, its civil liberties are rated 3.2 out of 10, and its political culture 5.6, but its electoral process is given a 0. Freedom House echoes these figures, giving Tunisia a 5 out of 7 (higher) for civil liberties but a 7 (lower) for political rights. We see similar trends in Egypt. The EIU gives it 5 out of 10 for political culture and 3.5 for civil liberties, but only 0.8 for its electoral process. Similarly, Egypt is given a 5 (higher) for civil liberties, but a 6 (lower) for its political rights by Freedom House. According to the EIU, Libya scores 5 out of 10 for political culture and just 1.5 for its civil liberties, but 0 for its electoral process. According to Freedom House, Yemen as well has greater civil liberties (5) than its political rights (6). Finally, Syria: though its political culture is ranked by the EIU 5.6 out of 10 and its civil liberties 1.8, its electoral process rating is also 0. Freedom House again agrees here, giving Syria a lower political rights ranking (7) than its civil liberties (6).23 And, according to the World Bank, not one of these countries has had a “voice and accountability” ranking greater than the 15th percentile in the past three years, with some (Libya, Syria) barely breaking the 5th percentile.24 The difference of one or two points on a 0-to-10 or 7-to-1 scale may not seem like much, but it likely proved just enough to set the process of revolt in motion. So, in sum, there appears to be an inherent contradiction in the sort of soft authoritarianism seen in many of these Middle Eastern states. In many cases, the people were free to choose their own jobs, their own religions, even their own civil society organizations, but not their own leaders. And this taste of freedom they have been given seems to have set off a ravenous hunger, which may not be satiated until all of the dictators are gone.

ARAB SPRING IN PYONGYANG?

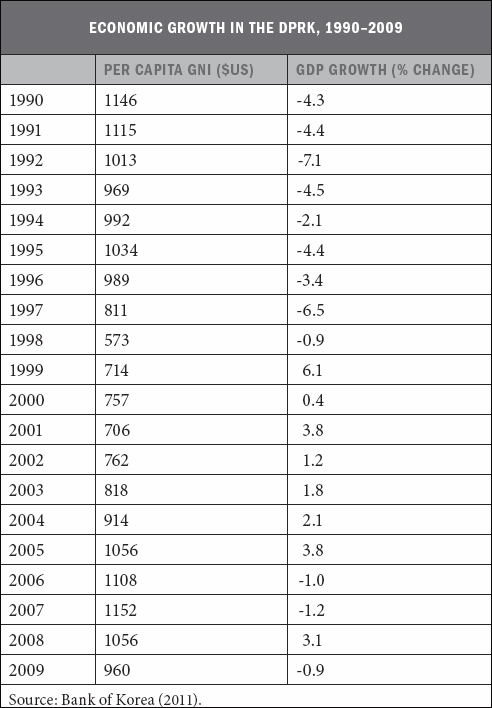

There are five potential variables—wealth accumulation, rates of growth, demography, contagion effect, or regime type—that could bring the Arab Spring to North Korea’s doorstep. Do we see the possibility for change in the DPRK from any of these? Not really. There is no development gap in North Korea. Wealth accumulation and economic growth have not been apparent. Rather than modernizing and growing, the society has seen little development. Traversing the streets of Pyongyang, one is struck by how the city skyline and streets, though neatly maintained, have not really seen any development since the 1960s. Not just the architecture, but the public phone booths, trolley cars, streetlamps, and other fixtures all look over forty years old. The economy has been contracting. GDP growth, when it was not contracting in the 1990s, has trudged along at unimpressive rates. Per capita gross national income, moreover, has been decreasing over the past two decades from $1,146 in 1990 to as low as $573 in 1998, and reaching $960 in 2009, which is still a net decrease from two decades earlier.

Other signs of a modernizing consumer-oriented society are just not present. Life expectancy is 67.4 years, down from 70.2 years in 1990.25 One-third of the population is undernourished.26 Given this state, the people of North Korea do not entertain notions of demanding a new political leadership that can improve their lifestyles. Rising expectations only come with a degree of hope, which is nonexistent. Instead, the people are preoccupied with survival, finding their next meal, and staying warm in the depths of winter.

North Korea does have a relatively young and literate population, two important variables for the Arab Spring. The median age is 32.9 years and literacy rates are near 100 percent. But the likelihood of a “youthquake” is remote. Contrary to what many may think, the North’s poor economic performance does not translate into widespread idle and unemployed youth susceptible to lashing out at the government. First of all, as a Communist economy, North Korea technically has no unemployment rate, as everyone works for the state. Of course, given that the state cannot pay the workers for months at a time, this population would by any other definition be considered unemployed. But this does not lead to idleness, because most workdays are spent devising coping mechanisms to subsist. The average factory worker at a state-owned enterprise might choose not to continue to work at the factory because he is not getting paid, but he will not quit his job. Instead, he will report to work in the morning, punch the time clock, and then bribe the foreman to allow him to spend the day trying to catch fish or forage for scrap metal that he can sell on the black market. Aside from these coping mechanisms to occupy their time, all young males are gainfully employed for up to twelve years in the military. The DPRK has a military conscription system where service in the army is between five and twelve years, service in the navy five to ten, and in the air force three to four years; by a very wide margin, the longest service terms in the entire world.27 Thereafter, all are obligated to serve part-time until forty and must serve in the Worker/Peasant Red Guard until sixty.28 This system is set up ostensibly to keep the military strong, but it also serves the purpose of keeping young men harnessed and off the streets. Finally, leisure time in North Korean society, to the extent that it exists, is largely spent in ideological indoctrination. There is no idle time when one is serving the Dear Leader. After school, for example, students will march with their work units to the square in front of Kim Il-sung’s mausoleum to practice performances for the spring festival, or they will be in sessions reading about the greatness of Kim Il-sung’s thought. There do not appear to be objective indicators of an impending youthquake in North Korea any time soon.

What about a contagion effect? Can news of what happened in the Middle East and North Africa spread to the DPRK? Could a demonstration effect occur where North Koreans do not necessarily identify with the frustrations of a Tunisian street merchant, but where they simply learn of the fact that popular protest is a mode of expressing needs and effecting change? One of the major priorities of human rights NGOs on North Korea in the aftermath of the Arab Spring was to try to get as much information as possible into the country about the unprecedented events. After the 2010 artillery shelling of Yeonpyeong Island, the ROK military sent nearly three million leaflets into North Korea, describing the Arab Spring. Another method entailed flying hot-air balloons from islets off the west coast of the peninsula into North Korea. Packages attached to these balloons carried money, food, and newspaper reports about events in the Middle East. If the winds blew in the desired direction, these balloons would land in the North and disseminate the kind of information that bursts the bubble of tightly controlled information the regime seeks to maintain. But these launches are small-scale when it comes to educating an entire population; moreover, they put North Koreans at great risk if they are caught by state authorities with these materials. Human rights–based and reform-advocacy radio broadcasting NGOs, such as Radio Free Asia, Radio Free Chosun, and NK Reform Radio, also broadcast news of the events in the Middle East into North Korea on a daily basis. But the signals for these broadcasts are often well jammed by the DPRK authorities, and most North Koreans don’t have access to the kinds of radios that can pick them up anyway.

In order to create a contagion effect, you need high literacy rates and social media, or a somewhat-free press. In North Korea’s case, you clearly have the former but neither of the latter. There is no access to the World Wide Web from within the country, and the only Internet that exists is an “intranet” that connects to tightly controlled government Web sites. There is only one Twitter and Facebook account in the whole country (set up by the government). All of North Korea’s television stations are state-run, with no regional or even inter-Korean Al Jazeera–type networks. And, based on the latest statistics, there are only about five TVs for every hundred North Koreans.29 There is no foreign travel, and domestic travel is severely restricted. And it is safe to say that the average North Korean is oblivious to the plethora of personal media and entertainment devices that have become staples in our lives. When I traveled to Pyongyang in 2007, I was allowed to keep my iPod, largely because the airport security personnel did not know what the device was. I assured them it could not be used as a communications device within the country (there is no wireless Internet), and had only music and videos on it.

The two most interesting recent developments in this regard have been the introduction of cell phones into the country and the opening of a new computer lab at the Pyongyang University of Science and Technology (PUST). The North Koreans introduced cell phones into the country only for the elites in Pyongyang, but in 2004, it banned them after an explosion at a local train station looked uncomfortably close to an assassination attempt on Kim Jong-il. In the rubble of the blast, officials found what looked to be evidence of a cell phone–detonated bomb. In 2008, the Egyptian company Orascom won the exclusive contract worth $400 million to provide cell phones in North Korea.30 The first year of operation in 2009 started with 70,000 units. There are nearly one million units now in Pyongyang, but this only represents about 3.5 percent of the population, and the phones do not have the capacity to dial outside of the country. PUST was opened in October 2010 through the efforts of evangelical Americans and a combination of academic, Christian, and corporate-world funders in South Korea.31 The facility features 160 computers, for which a select group of university students are being trained. The use of these computers, however, is heavily restricted to these select students, whose job is to glean from the Internet information useful to the state. By comparison, Tunisia had 40 percent of its population conversant with the Internet. This level of exposure to outside information in North Korea is miniscule when compared with that of the Arab countries.

North Korea remains the hardest of hard authoritarian regimes in the world. Unlike South Korea in the 1980s, which shifted to a soft authoritarian model with a burgeoning middle class that eventually demanded its political freedoms in 1987, the North has resisted all change. Those who visit Pyongyang come out claiming life does not look so bad. People walk freely in the streets without omnipresent military patrols. Society seems very orderly. There are no urban homeless visible. CNN broadcasts from Pyongyang showed city dwellers attending a street carnival, eating cotton candy, and texting on their cell phones. These episodic reports, however, mis-portray a terribly restricted society with draconian controls on all liberties. North Korea still ranks seven out of seven (lowest possible score) on Freedom House’s Freedom in the World index, and it has thereby earned the odious title of “the Worst of the Worst,” for its political rights and civil liberties record.32 It sits dead-last of 167 countries on the EIU’s democracy index.33 It is in the 0th percentile for the World Bank’s Voice and Accountability index and is ranked 196 out of 196 countries in the Freedom of the Press index.34 What is astonishing about these rankings is not the absence of movement to a softer form of authoritarianism, necessitated by the need for economic reform, but that the regime has consistently maintained such controls decade after decade with no letting up whatsoever. This persistence stems not from a lack of understanding that some liberalization is necessary for economic reform, but from the Kim regime’s conscious choice to prize political control over anything else. This puts the Kim regime in a class of authoritarianism of its own.

According to respected scholars of political diasporas, creating political change at home often requires outside resources and a vibrant expatriate community with a political agenda to push for change.35 But there is no real dissident exile community for North Korea like the ones we see with Egypt, Iran, and other cases. Defectors from North Korea show anger toward their former prison guards or toward corrupt bureaucrats, but this, surprisingly, does not aggregate into an anger to expel the Kim leadership. A July 2008 survey of refugees in Seoul, for example, found that 75 percent had no negative sentiment for Kim Jong-il.36 Kang Ch’ŏl-hwan, the defector who wrote the famous book Aquariums of Pyongyang, displayed anger in his writing toward the guards in his prison camp but not to Kim Il-sung. A National Geographic documentary, Inside North Korea, followed around the country an eye doctor who performed cataract surgeries for ailing citizens.37 After thousands of surgeries, upon having their bandages removed, every single patient immediately and joyously thanked for their renewed eyesight Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il, not the doctor. Even news of Kim Jong-il’s stroke elicits from a defector empathy rather than anger:

[I don’t know] whether I should reveal my sadness over Kim Jong-il’s health . . . He is still our Dear Leader. It is the people who work with him and give him false reports who are bad. When I hear about his on-the-spot guidance and eating humble meals, I believe he cares for the people.38

This is not to say that dissident movements started by North Korean defectors are wholly absent. The Committee for the Democratization of North Korea (CDNK), Fighters for a Free North Korea (FFNK), and the Citizens’ Alliance for North Korean Human Rights are examples of NGOs devoted to creating political change in the North, but relative to other cases, these movements are small and do not pose a direct threat to the regime.

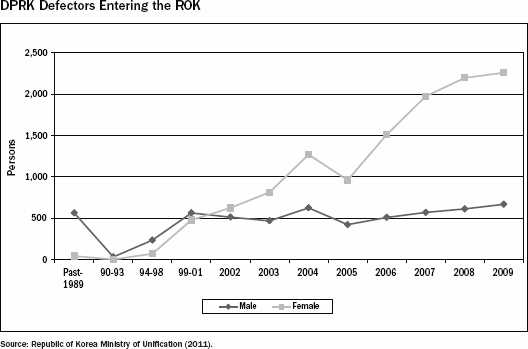

There are several reasons for the lack of a politically active exile community. First, the recent migrants out of North Korea are almost all female and are leaving the country purely for economic reasons. Some 75 percent of recent defectors are from the northern Hamgyŏng provinces, which is the worst economically hit area of North Korea. Women, therefore, leave the country purely as an economic coping mechanism to survive rather than to act out political ambitions against the regime. Prior to the 1990s, the flow of refugees might have been more liable to protest as it was constituted of male political elites and military officers, who left for ideological reasons or because they were accused of committing state crimes. The numbers of these, however, were fairly small (607 total between 1949 and 1989), compared with the recent wave (nearing 22,000 currently resettled in South Korea).39

Second, as noted in previous chapters, defectors from North Korea have significant enough difficulties adjusting to life outside of the North, which preclude the luxury to entertain ideas about promoting political change in their former home country. Life in South Korea, where many of these defectors resettle, is fast-paced and often filled with social challenges, including disadvantages due to a lack of education, physical diminutiveness compared to well-fed southerners, and social discrimination in terms of jobs and marriage. Many northerners are preoccupied with meeting these challenges, as well as with paying off brokers’ charges as high as $6,000 for their successful escape to a life that is different, undoubtedly free, but challenging nonetheless. For this reason, many northerners still feel a sense of pride about their former homeland, and though they are fully cognizant of its shortfalls, most said that if they had to do it all over again, they would still be happy to have been born in the North.

CEAUSESCU’S MOMENT

By all of our political science metrics, the DPRK shows no potential to have an Arab Spring. But then why has the North Korean regime seemed so worried? Why did it stifle the inflow of all news regarding events in Libya, Egypt, Tunisia, and Syria? Why did it amass tanks and troops in urban centers as a precaution against public gatherings? Why did Kim Jong-il issue a personal directive in February 2011 to organize a special mobile riot squad a hundred-strong in each provincial office of the Ministry for People’s Security? Why did it bolster surveillance of all organizations on university campuses and then issue a decree in 2011 closing all universities for months and sending all students to work units? Why did the government order a countrywide inventorying of all computers, cell phones, flash drives, and MP3 players among the elite population? Why did it crack down on all public assembly, even to the extent of removing dividers in restaurants to prevent private gatherings? Why did they threaten to fire artillery on NGO balloons from offshore South Korean islets carrying news of the Arab Spring into North Korea?40

Indeed, there seems to be a significant gap between what theories of revolution tell us and what the gut instincts of the DPRK leadership tell. The regime’s actions reflect a sense of vulnerability. For Kim Jong-un, the stark fact is that dictators who held power much longer than his late father—like Qaddafi of Libya, Mubarak of Egypt, and Ben Ali of Tunisia—all have fallen from power, or have been hanging on by their fingernails. This must have sent a chilling message. The fact that all of the political science indicators for revolution were in existence but dormant in the Middle East and North Africa till now must give junior Kim little comfort about the absence of any such indicators in his own country.

The main lesson of the Arab Spring is that authoritarian regimes, no matter how sturdy they look, are all inherently unstable. They maintain control through the silence of people’s fears, but they also cultivate deep anger beneath the surface. Once the fear dissipates, the anger boils to the surface and can be sparked by any event akin to a Tunisian police officer slapping the face of a street merchant. The late North Korean leader Kim Jong-il once admitted to Hyundai founder Chŏng Chu-yŏng to having dreams where he was stoned to death in the public square by his people.41 What the Dear Leader and the Great Successor fear is their “Ceausescu moment.” Condoleezza Rice explained this at a 2011 meeting at the Bush Presidential Center in Dallas, Texas, as the moment where the Romanian dictator went out into the streets to quell protests by declaring all the positive things his rule had done for the people. A quieted crowd, once fearful of the leader, listened. Then, after a pause, one elderly woman in the crowd yelled out, “Liar!” and others joined in the chant, replacing their fear of the dictator with anger against him. Ceausescu was subsequently executed in the streets of Trâgoviâte, Romania. Kim Jong-un thus must feel like he is living on borrowed time. A collapsing domino row of dictators, many of whom were personal friends of his father and grandfather, becomes the larger context in which the junior Kim is trying to take over for his dead father. Blocking information about the Arab Spring and taking precautions to stifle all public assembly becomes paramount.

The post–Kim Jong-il leadership must be paranoid about the Arab Spring, because it is watching fellow dictators lose control in the context of dramatic changes in their own societies, and Kim Jong-un has his own challenges stemming from a changing North Korean society. There are two forces at work here in diametrically opposed ways: marketization and ideological reification. After the 2002 economic reforms allowed some markets to spring up in the North, the society changed permanently. Recall from chapter 4 that Pyongyang undertook these reforms, which lifted price controls and introduced market mechanisms, not because of a newfound love for liberalization but because the PDS had broken down and the government was essentially telling the citizens to fend for themselves. Markets opened everywhere and society permanently changed after that. Even with the government’s reinstitution of the ration system and crackdown on market activity, citizens refused to rely solely on the government, and, according to defectors, the majority of North Korean citizens today rely on the markets for some significant portion of their weekly food, goods, and a wide range of other products. Farmers meet their production quotas and then sell their best produce in the market. Or factory workers at the Kaesŏng Industrial Complex save their Choco Pies from the cafeteria lunch and sell them on the black market. A 2008 study by Stephan Haggard and Marcus Noland found that more than two-thirds of defectors admitted that half or more of their income came from private business practices. More than 50 percent of former urban residents in the DPRK reported that they purchased as much as 75 percent of their food from the market. These numbers were reported, moreover, when the government was in the midst of a crackdown on markets and aiming to reinstitute the PDS. These markets in North Korea have become a fixture of life that now is virtually impossible to uproot.

Markets create entrepreneurship. And entrepreneurship creates an individualist way of thinking that is alien to the government. This change is slow, and incremental, but it affects a good part of the population and is growing every day in a quiet but potent way. The change was evident in the way in which the people responded to the government’s effort to crack down definitively on marketization by instituting a currency redenomination in 2009. This redenomination wiped out the hard work of many families who could exchange only a fraction of their household savings for the new currency. People reacted not with typical obedience out of fear, but with anger and despair. Some committed suicide. Others fought with police who tried to close down the local market. Still others scrawled antigovernment graffiti on university walls. The greatest vulnerability for a regime like North Korea is when a population loses its fear of the government. Once the fear is gone, all that is left is the anger.

NEOJUCHE’S IDEOLOGICAL RIGIDITY

The inescapable dilemma for Pyongyang is that its political institutions cannot adjust to the changing realities in North Korean society. It can take short-term measures to dampen the anger. After the botched currency redenomination measure, for example, Pyongyang tried to adjust by raising the ceiling on the amount of old currency that citizens could exchange. They also shot in public the seventy-six-year-old director of Planning and Finance Department, as the scapegoat for the policy mistake. But in the longer term, North Korean political institutions and ideology are growing more rigid, not more flexible, as the leadership implements the third dynastic passing of power within the Kim family. Neojuche revivalism is in many ways the worst possible ideology that the regime could follow in parallel with the society’s marketization. The ideology’s emphasis on reliving the Cold War glory days through mass mobilization and collectivist thought is, in fact, the complete opposite direction from that in which society is moving. And yet, the government cannot adjust its course because: (1) it needs a new ideology that has a positive vision for a new leader (and the only positive vision the state ever experienced was early Cold War juche); and (2) it attributes the past poor performance of the state over the last two decades not to Kim Jong-il but to the “mistakes” of allowing experimentation with reform, which “polluted” the ideology. Another lesson that Pyongyang learned from the Arab Spring was that this new neoconservative juche ideology must be implemented without giving up their nuclear weapons. The example of Libya made clear to North Koreans that Qaddafi’s decision to give up his nuclear programs to the United States was an utter mistake: precisely because he no longer had these capabilities, NATO and the United States were at liberty to take military actions against him.

This confluence of forces gives rise to a ticking time bomb—or a train wreck in slow motion, whatever metaphor you prefer. A dead dictator compels a rushed power succession to his son, and the regime pushes an ideology that moves the country backward, not forward. Meanwhile, society is incrementally moving in a different direction from North Korea’s past—in large part, sparked by the economic failures of the government. One might call this a North Korean version of Samuel Huntington’s development gap. Rather than economic growth outpacing static political institutions in an unstable, democratizing society, you have a growing gap between a rigidifying ideology and slowly changing society in North Korea. A single event—akin to a botched government measure or a severe nationwide crackdown on markets—could spark a process that could topple an already brittle dictatorship. A young and inexperienced dictator will in all likelihood fail spectacularly to cope with this ideology-society gap. In the end, the new regional leaders, including the United States, Russia, China, and South Korea, who take the reins of power in 2012, will be faced with fundamental discontinuities in North Korea before they leave office.

Pyongyang’s fears about the Arab Spring also presumably derive from an understanding of the role social media played in those countries, and the realization that the recent baby steps by the DPRK into acquiring cell phones and accessing the Internet have the potential to puncture the hermetically sealed information bubble around the country. As I noted earlier, recent North Korean ventures are modest by comparison with the Middle East states, so there is little chance of a technology-driven contagion effect today. Indeed, the regime sees these technology instruments as enhancing the state’s power, not weakening it. But their introduction creates a slippery slope for the regime with regard to information penetration. The Internet, for example, is like marketization. Once a society is exposed to it even a little, the conveniences associated with it become a fixture of life that is very difficult to uproot. North Korea is, ironically, a country that desperately needs the Internet—its citizens are not allowed to travel overseas, and yet the country wants information from the outside world cheaply and without a lot of interaction. Access to the Web handsomely meets these needs. In 2003, the DPRK set up their official Web site, uriminzokkiri.com, hosted on a server in Shanghai, and in 2010 the government joined Twitter and Facebook. The government wanted to carefully restrict all use of the Web, but then they realized that the Internet allowed access to information instantaneously and costlessly, without having to send anyone abroad to get it. Moreover, the government realized that greatly restricting international access to their Web sites undercut the purposes of trying to attract foreign direct investment. In meeting these needs, the government started walking down the slippery slope, gradually relaxing restrictions. Now, there are twelve Web domains in North Korea, and about a thousand government and nongovernment users of the Internet, albeit greatly censored.42 Some users must be fairly sophisticated, given reports about hacking attempts on ROK and U.S. government sites originating from within North Korea. The PUST project is another step down the slippery slope, as it teaches some of Pyongyang’s best and brightest youth how to use the Internet. While this is limited to only a handful of carefully selected students who are monitored at all times as they download information useful to the state, the basic fact remains that there are youth in North Korea who know how to surf the Web and will someday gain access to a South Korean or Chinese computer that is not monitored. Cell phones followed a similar trajectory. The government eventually reintroduced them to the country after the 2004 Ryongch’ŏn train blast and the number of phones continues to grow every year.

The purpose of phasing in these devices was to serve the state. Phones would enable better communication among the elite and another means of coordination and control among security services. Seventy thousand units were introduced for the elite in 2009, but this turned into nearly half a million phones by April 2011, and predictions are they could go as high as 2 million units by the end of 2012. These phones cannot call outside of the country, but they do give a broader portion of the population familiarity with phones, texting features, and Web access. Moreover, there are an estimated thousand phones smuggled in from China with prepaid SIM cards. With these phones, North Koreans near the Chinese border can call within the DPRK and to China, and, reportedly, as far as Seoul. Again, these are small steps, carefully controlled by the government, and do not come near replicating the use of social media in other parts of the world. But the Internet and cell phones are truly a slippery slope for the regime. They quickly become fixtures of life, and a new generation of North Koreans will be literate in these technologies.

Finally, the North Korean leadership evinces a growing discomfort with the way the fight for freedom in distant Arab states reverberates internationally. Analysts talk about a new wave of democratization and hypothesize whether it will move to Asia. This raises concerns about international recognition of human rights abuses in the DPRK. As late as 2004, it was fair to say that outside of the human rights movement, the global community did not acknowledge the plight of the North Korean people. Among the many other causes around which the world organized, North Korea was notably absent.

But, thanks in large part to efforts by the United States, this is no longer the case. Both Presidents Bush and Obama have succeeded in connecting the cause of the North Korean people with the global American agenda of promoting freedom and human dignity. Bush, in particular, was the first U.S. president to appoint a congressionally mandated special envoy for human rights abuses in North Korea. He was the first U.S. president to make a statement protesting China’s refoulement of North Korean refugees, and to allow for a refugee resettlement program for North Koreans in the United States. Bush also invited the first North Korean defector into the Oval Office, Kang Ch’ŏl-hwan. The meeting was a private one, not listed on the president’s official schedule. But afterward, the decision was made to release only one picture of the meeting to the Associated Press with a simple caption saying the president welcomes Mr. Kang to the Oval Office. The picture spread like wildfire around the world. It did not spur human rights protests within North Korea, because the government did not allow the picture into the country, but it did create an international contagion effect. The world suddenly was awakened to the abuses inside North Korea. Newspaper editorials in Asia questioned why their governments did not have a North Korean human rights envoy, or why their leaders had not read Aquariums of Pyongyang like Bush had done. G8 countries put the issue on their agenda and released statements condemning the government’s atrocities against its people. Obama maintained U.S. focus on this issue under his administration, so that in May 2011, the DPRK for the first time allowed a visit by the U.S. human rights envoy, Ambassador Robert King. In short, how the DPRK runs its country is now under the magnifying glass more than ever before. And the Arab Spring only highlights how tenuous an authoritarian regime’s control can be, and how the breakdown of this control can capture the imagination and support of the free world.

Skeptics might argue that my speculation about the regime’s limited days is not borne out by the history of the regime’s stability. The fact is, skeptics would argue, that there have been no instances of coups or domestic instability in the North over the past fifty years, like we have seen in South Korea, for example, with two military coups—in 1961 and in 1979—that overthrew standing governments. The people are too weak and the military and state controls are simply too strong for anything untoward to happen to the leadership. However, if we quickly peruse the history, domestic disturbances are not exactly an unknown occurrence in the North. These have taken place within the military, between the military and the citizens, and even against the leadership.

In 1981, there were reports of armed clashes between soldiers and workers in the industrial center of Ch’ŏngjin, on the eastern coast of the country, that left as many as five hundred dead. In 1983, there were Soviet-based reports of similar clashes in Sinŭiju. In 1985, there were reports of a massacre of hundreds of civilians in Hamhŭng over food. In 1990, a small group of students at the elite Kim Il-sung University reportedly were arrested and tortured for organizing protests. In January 1992, there were reports of a failed attempt by officers in the State Security Department’s bodyguard bureau to stage a coup preventing Kim Jong-il from assuming the position as commander of the KPA. In April 1992, rumors surfaced that thirty officers were executed for a failed plot to assassinate Kim Jong-il. In March 1993, thirty officers of the VII Corps headquarters stationed in Hamhŭng tried unsuccessfully to stage a rebellion against their superiors. In 1995, upset with Pyongyang’s decision not to ship food to the Hamgyŏng provinces, senior officers of the VI Corps stationed in Ch’ŏngjin sought to take control of a university, communications center, Ch’ŏngjin port, and missile installations, and, reportedly, planned to team up with VII Corps in Hamhŭng to oppose the government. In December 1996, leaflets were found in front of Kim Il-sung mausoleum, criticizing the costs of the mausoleum when citizens were starving. In 1997, a statue of Kim Il-sung was found vandalized and reports of anti-regime graffiti were found. In March 1998, there was a report of a failed assassination attempt by one of Kim’s bodyguards. In late 2001–early 2002, there were reports of another failed assassination attempt on Kim by one of his bodyguards. In 2004, a terrorist bombing at Ryongch’ŏn station killed 170 people, narrowly missing Kim Jong-il’s train as it passed through the station returning from a trip to China. In 2005, a video surfaced online that showed a nervous youth under a bridge in rural North Korea, hanging a banner that denounced Kim Jong-il in bright red letters and was signed by the “Freedom Youth League.” In December of 2007, when the government decided to ban market activity for women under the age of fifty (by far the most important group in the markets), protests sprang up in Ch’ŏngjin within months, with female participants reportedly calling out, “If you do not let us trade, give us rations!” and “If you have no rice to give us, let us trade!”43 In 2009, whole families committed suicide over the government’s surprise currency redenomination measure that wiped out their life savings. In Hamhŭng, fights broke out in markets that police officers unsuccessfully tried to close down. Anti–Kim Jong-il graffiti was found in alleyways. In 2011, “Down with Kim Jong-un” messages were found scrawled on university walls and in markets. And the list goes on. It is hard to confirm the severity of these incidents, because no one inside the country can report on them. It is also impossible to know whether these reports represent the entirety of dissent within the North or only the tip of the iceberg. Most of the reports of dissent occurred in the 1990s, after Kim Il-sung’s death and during the famine years. But we do not know if the dissent has disappeared or if the government has just gotten better at stifling news of it. It is clear, however, that internal dissent is not unheard of, despite the draconian controls of the DPRK system. It has emerged in the past. It can emerge again.

But who would be North Korea’s Bouazizi? Two possible sources of discontent might be the “selectorate” and the urban poor. The “selectorate” refers to the elite in North Korean society—party members, military officers, and government bureaucrats who have benefited from the regime’s rule.44 Their support is co-opted by the state through the promise of benefits doled out by the leadership. They are the most loyal, ranging in number from two hundred to five thousand, according to different estimates. And to retain their loyalty, they are showered with benefits, such as highly coveted employment positions, desirable residences, plentiful and high-quality foods, and access to luxury items such as red meat, liquor, and other imported goods. In many cases, elites are even given lavish gifts, such as luxury cars, jewelry, electronics—even wives.45 In 2005, after we had achieved the Six-Party Joint Statement, we heard that Kim Kye-gwan, the DPRK lead negotiator, was given a new Mercedes-Benz sedan. (I, on the other hand, got to watch a preview of James Bond: Casino Royale in the White House Family Theater, with the president and about fifty NSC and domestic staff whom President Bush thanked for their hard work.)

Some scholars claim that Kim Jong-il has “coup-proofed” himself by prioritizing the bribing of these officials over any broader economic performance metrics for the state. But this loyalty lasts only as long as the regime can continue the handouts, and the government’s capacity in this regard is increasingly shrinking. The cumulative effect of years of U.N. sanctions on luxury goods, the continued decline in the economy, and the inability of China to backstop the regime forever will take its toll, making the circle of the selectorate smaller and smaller. Favorites will have to be chosen to receive the shrinking handouts, leaving some disaffected. The rushed leadership transition from Kim Jong-il to Kim Jong-un, moreover, promises even more disaffection in the party and military, as the new Kim will have to choose his inner circle as his basis of leadership, which will send ripples throughout the selectorate, giving opportunities to some but, more ominously, taking opportunities away from others.

Moreover, as neojuche ideology puts more strain on the economy, the segment of society that will feel the most pain are the urban poor. In 2002, when the DPRK undertook economic reforms that lifted price controls, the resulting inflation badly hurt salaried urban populations, who suffered increases in their cost of living. While farmers could offset this with the higher prices they enjoyed from the sale of their own produce in the black market, urban workers faced a double whammy—higher prices and delayed salary disbursements from the government. The result is a potentially unhappy urban population that is literate, educated, and may have more knowledge of the outside world than most others in the country. Moreover, they identify with the system because they once benefited from it, which may give them cause to regain those advantages. And they probably have cell phones.

FIVE POLICY PRINCIPLES

So what should the United States and its allies do until the fateful day comes? Fashioning a comprehensive policy to deal with North Korea’s nuclear programs, its human rights abuses, and its failed economy is hardly child’s play. No administration thus far has been successful at addressing one, let alone all three. The specifics of a policy will depend on the circumstances at any given moment in time. Policy operates on tactics as much as it does on strategy. Often the tactics overcome the strategy, as governments are forced to react piecemeal to DPRK provocations. But there are some core principles in which any administration must embed its thinking about North Korea.

First, any administration must understand that patience is part of a policy to wait out the regime. Thirty-plus years of U.S. diplomacy, practiced by some of our best diplomats and statesmen, have proven this point. As frustrating as need for patience can sometimes be, the alternative policy of pushing the regime toward collapse only triggers counterbalancing forces in the region (i.e., China) that keep the regime afloat with more assistance and backdoor support. The military option has the potential to be extremely costly if it escalates to all-out war; moreover, it may not be successful. A surgical strike on the Yongbyon nuclear complex still would not guarantee that all weapons and programs, which may be hidden throughout the country’s caves, had been eliminated. An operation to take out the leadership of North Korea is probably within the realm of U.S. capabilities, given the successful operations against Saddam Hussein and, more recently, Osama Bin Laden. But any future president is unlikely to take this route. A Presidential Finding for a covert operation of this magnitude would mean that the United States had made elimination of the North Korean leadership a top priority just like in the case of Iraq and Al Qaeda. No administration thus far has prioritized the problem to this extent. It remains a second-tier problem at best, and when it periodically erupts into a crisis, then the modus operandi is to stabilize the situation, not to end the problem. United States’ relative indifference is probably the North Korean regime’s greatest blessing. The only circumstance in which North Korea might appear in our crosshairs is if a terrorist attack on the homeland was traced to weapons that originated in North Korea. Should that day come, the regime’s days would be numbered.

Second, any administration must consider as the baseline of its policy a robust set of counterproliferation and financial sanctions. The Obama administration oversaw the creation of a U.N.-backed international regime of sanctions against the North based on Security Council Resolution 1874. These sanctions must continue with an emphasis on closing loopholes that allow the DPRK to receive intermediate goods for production of more missiles or development of their plutonium- and uranium-based nuclear weapons. Vigilant efforts like the Proliferation Security Initiative—a ninety-plus-country multilateral institution dedicated to stopping, at ports or in transit, the movement of WMD and component parts—must continue to focus on North Korea as one of its main targets. Two major areas of improvement in the PSI are better cooperation from China on land crossings with the DPRK and the closing off of Chinese and Russian airspace to suspect DPRK cargo and passenger flights. An equally important piece is to engage with potential customers and secondary facilitators of North Korean military wares, and persuade them that any transactions with the North would be ill-advised and subject to secondary sanctions. Financial sanctions that target the activities of DPRK front companies engaged in proliferation financing, and that also target the personal finances of the leadership, have proven to be effective. All of these measures force the leadership in Pyongyang to focus their energies on finding different ways to circumvent the sanctions. This conveys the message to the leadership that the costs of their nuclear program carry long-lasting penalties that outweigh the benefits. Ideally, all or any one component of this battery of sanctions should not be up for negotiation with the North. These sanctions are designed for counterproliferation; therefore, as long as the North maintains a single nuclear weapon, the sanctions should remain in place. They should end only when the last nuclear weapon is taken out of North Korea. No sooner.

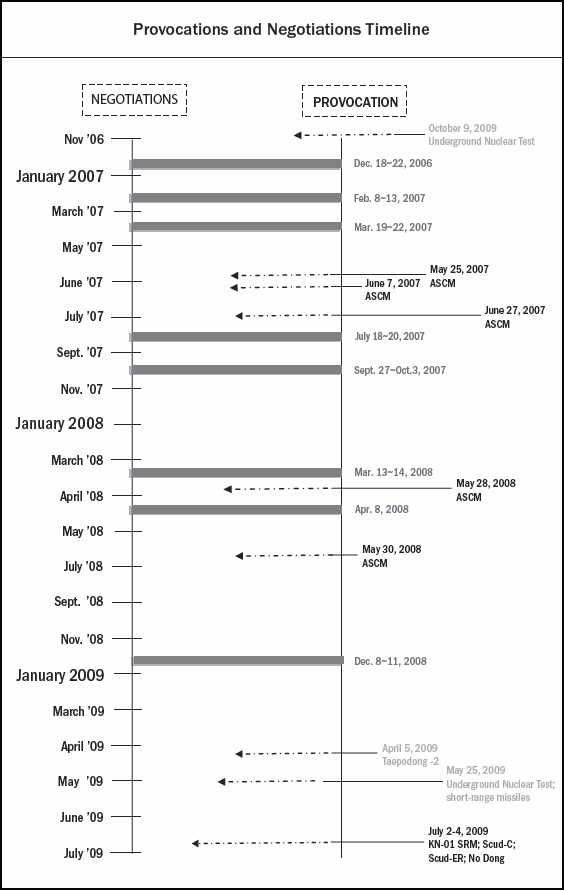

Sanctions have been and will continue to be the primary means of addressing the North’s vertical (development of own programs) and horizontal (selling to others) proliferation potential. However, these sanctions contain North Korea; they do not denuclearize North Korea. That is, a thirty-year campaign of sanctions may help to stop proliferation, but they do not force the government to give up their nuclear weapons. Thus, the third principle is negotiation. Any administration will, at some point in its dealings, be compelled to negotiate with North Korea. Indeed, every administration for the past twenty-eight years—some with the toughest stances on North Korea—has sooner or later entered into a dialogue in order to freeze Kim’s programs and ultimately dismantle pieces of it. Given all the past violations of agreements, the North’s ludicrous rhetoric, and their flagrant nuclear and missile tests, the thought of sitting down with them and hammering out painstaking new agreements may seem entirely distasteful. Washington, D.C., inside-the-Beltway pundits would point to three decades of U.S. negotiations that have provided the North with over $1.28 billion in benefits, and in return received two nuclear tests and thirty-three ballistic and cruise missile tests (since 2006 alone), and scoff at any future administration that got fooled into negotiations again.

But for a pundit, it is easy to say there should be no talks whatsoever with North Korea. From the perspective of policy, however, lack of negotiations has its costs, because you are left with a runaway nuclear program with no insight into where it is headed and with whom it is interacting. The term of art, therefore, is “you must hold your nose and negotiate.” Negotiations have three objectives. First, they aim for denuclearization, however distant that goal may appear. One can never abandon this as the objective of negotiation, because it would imply that the United States and allies have resigned to accepting the DPRK as a nuclear weapons state, in which case negotiations would be about reductions in their arsenal—i.e., an arms control negotiation, not a denuclearization negotiation. Second, these negotiations help to manage escalation and prevent crises. A study conducted at CSIS charted all North Korean major provocations on a weekly basis, dating from March 1984 through the present. It then superimposed on this chart a graph of all periods of major negotiations between the United States and DPRK in bilateral or multilateral formats (e.g., Four-Party, Six-Party Talks). Over three decades, there has only been one instance in which DPRK provocations took place during ongoing negotiations (August 31, 1998, missile test). Thus, dialogue does appear to help prevent crisis and escalation, which some administrations may see as an important goal (although the end of that dialogue will be met almost certainly with more DPRK provocations, according to the CSIS study).

Third, negotiations, if successfully concluded, will result in agreements that get incrementally at pieces of the nuclear program. The DPRK will continue to keep their actual nuclear weapons as the last bargaining chip in any negotiation. Thus, any attempts at a single “mega-deal” that offers more incentives to get more in return may sound great, but these are all eventually whittled down by the North to smaller steps. It was maddening to hear pundits criticize the deals we concluded with the North as misconceived, because we were not successful at bringing home their nuclear weapons. Every negotiator in any administration wants to get the weapons first, but if the North won’t give them up, you are left with walking away from the talks and sparking a crisis. You, therefore, have to make do with hard-nosed negotiations to reach as far into the program as you can get. The negotiations and implementation of the first nuclear agreement in 1994 were able to achieve a freeze of the North’s nuclear operations. The Six-Party Talks agreements of 2005 and 2007 were able to get beyond a freeze to partial dismantlement of its nuclear programs. To borrow a football analogy, negotiating with North Korea is not done with the eighty-yard-long pass. It is a ground game, where you are fighting to get one yard at a time.

The fourth principle of dealing with the North has less to do with Pyongyang and more to do with the surrounding countries. The subtext of any multilateral negotiations over North Korea’s nuclear program must be preparation for unification. It is one of the two contingencies in Asia that could plunge the region into crisis (the other is the Taiwan Straits), and yet the region is incredibly poorly prepared for it. After Kim Jong-il’s stroke in 2008, the United States and ROK made substantial progress in planning for how to respond to a collapse of the DPRK, but outside of these two countries, there is no regionwide plan. China is a key player, and yet it is remarkably unwilling to have conversations, even on a secret basis, regarding how to coordinate responses, even after Kim Jong-il’s death in 2011. Beijing is reluctant to do so for fear of leaks and because it does not want to give the impression that it is a willing accomplice in a plan to collapse the North. Yet some discussion is absolutely necessary. If the North collapses and the United States, ROK, and China have mutual suspicions of each other’s actions and no benefit of transparency based on prior consultations, then the margin for miscalculation and conflict is large. However, if we all have a prior understanding of what each country sees as its key vulnerabilities in a DPRK collapse scenario, there is less margin for error.

In recent years, former cabinet-level and NSC officials from the Bush administration (including the author) engaged in a Track 1.5 dialogue with Chinese counterparts, which was modestly successful in making first steps. The Obama administration has pressed this issue with the Chinese in their annual Strategic and Economic Dialogue, and the ROK government has undertaken its own back-channel discussion with Beijing led by Blue House officials, which has, reportedly, made progress. It is clear, for example, that the Chinese worry about refugee flows into their country if order broke down in the North. Beijing is also worried about a possible nuclear accident in North Korea (especially after the nuclear disaster in Fukushima, Japan, in 2011) and the need for humanitarian relief in the event of another famine in Hamgyŏng provinces. They are also uncertain about the disposition of the rash of mining and business contracts signed with the North in recent years if order breaks down in Pyongyang. The ROK’s top priority is to prevent migration into the South and to stabilize the humanitarian situation. Seoul also does not want any external power intervening without its consent. The U.S. top priority would be to secure the nuclear weapons and missile sites. Even these little kernels of information can constitute the start of mutually useful dialogue among Washington, Seoul, and Beijing.

Such preparations sound so commonsensical that to advocate them with urgency might appear comical. When I explain to long-term institutional investors in Asia, for example, that such preparations are not nearly as developed as one might think, many react with surprise that such a rational concern should not be addressed among even distrustful governments. But the fact of the matter is that it is hard to get governments to prepare for things that may happen tomorrow, because they are too busy reacting to things that happened yesterday.

The fifth principle for any future administration’s policy toward North Korea is not to forget about the people. The top-line issue for any administration is the threats posed by the North’s nuclear programs and other weapons. Yet when the regime eventually collapses, what is likely to be revealed is one of the worst human rights disasters in modern times. In this regard, among any administration’s policy objectives must be promoting measurable improvements in the lives of North Korean citizens and letting the North Korean people know that the United States wants to help them even as it opposes the DPRK government. Past administrations have laid out a template already, which future administrations can seek to improve on: a human rights envoy, a DPRK refugee resettlement program in the United States, food aid, advocacy to allow the UNHCR to interview North Korean defectors in China, and raising general international awareness of the human rights situation in the North.

Given the events of the Arab Spring, one of the key objectives of such a policy should be to use all means possible to increase the flow of information from the outside world into North Korea. Though the North Korean regime has done physical damage to its people through famine, imprisonment, and other draconian controls, perhaps the greatest human rights violation has been the effort to control the minds of its citizens by disallowing basic access to ideas. The DPRK regime is only as strong as its ability to control knowledge. This control enables the regime to stand on its ideology. Neojuche-ism and service to the Kim family is both the regime’s strength and its weakness. Without control of information, there is no ideology. Without ideology, there is no North Korea as we know it. The Kim regime knows that its biggest threat comes from within rather than from without, and therefore would oppose an information campaign. Thus the data or message does not have to be of a blatantly political nature, explaining the virtues of American-style democracy over juche ideology. Given the efforts to hardwire the brains of North Koreans, this message may be more than the wavelengths can bear. But one could increase radio broadcasting into North Korea to puncture the bubble of propaganda that suffocates the people every day. A related effort would promote a “skills campaign” designed to inject more basic know-how into the country. With enhanced knowledge of practical things such as medicine, agriculture, engineering, computers, and foreign language, the North Korean people can do better for themselves and in the process become empowered with understanding of the outside world. Rather than give only heavy fuel oil in exchange for the next freeze on their operating nuclear programs, for example, future administrations might consider offering vocational training, medical supplies, vaccinations, and basic computers as part of a denuclearization package. Other nations not part of the U.S.-DPRK confrontation might also be called upon, because they might have better success at providing needed skills to the people. Many countries now have diplomatic relations with the DPRK, including Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and Indonesia, and they could be more effective than the United States or ROK in proposing such programs. Given the panoply of sanctions against the DPRK, some coordination would be necessary to ensure skills could be offered in a way that is compliant with the sanctions. But a wholesale importation of such skills might in the end be more potent than any sanction. Outside information would strike at the core of the ideology. Improving people’s lives empowers them.

FINAL THOUGHTS