Operation Rolling Thunder: The History of the American Bombardment of North Vietnam at the Start of the Vietnam War

By Charles River Editors

A picture of bombing runs by F-105 Thunderchiefs

About Charles River Editors

Charles River Editors is a boutique digital publishing company, specializing in bringing history back to life with educational and engaging books on a wide range of topics. Keep up to date with our new and free offerings with this 5 second sign up on our weekly mailing list, and visit Our Kindle Author Page to see other recently published Kindle titles.

We make these books for you and always want to know our readers’ opinions, so we encourage you to leave reviews and look forward to publishing new and exciting titles each week.

Introduction

A picture of F-105Ds during the campaign

“Targeting bore little resemblance to reality in that the sequence of attacks was uncoordinated and the targets were approved randomly – even illogically. The North's airfields, which, according to any rational targeting policy, should have been hit first in the campaign, were also off-limits.” – Earl Tilford, U.S. Air Force historian

The Vietnam War could have been called a comedy of errors if the consequences weren’t so deadly and tragic. In 1951, while war was raging in Korea, the United States began signing defense pacts with nations in the Pacific, intending to create alliances that would contain the spread of Communism. As the Korean War was winding down, America joined the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization, pledging to defend several nations in the region from Communist aggression. One of those nations was South Vietnam.

Before the Vietnam War, most Americans would have been hard pressed to locate Vietnam on a map. South Vietnamese President Diem’s regime was extremely unpopular, and war broke out between Communist North Vietnam and South Vietnam around the end of the 1950s. Kennedy’s administration tried to prop up the South Vietnamese with training and assistance, but the South Vietnamese military was feeble. A month before his death, Kennedy signed a presidential directive withdrawing 1,000 American personnel, and shortly after Kennedy’s assassination, new President Lyndon B. Johnson reversed course, instead opting to expand American assistance to South Vietnam.

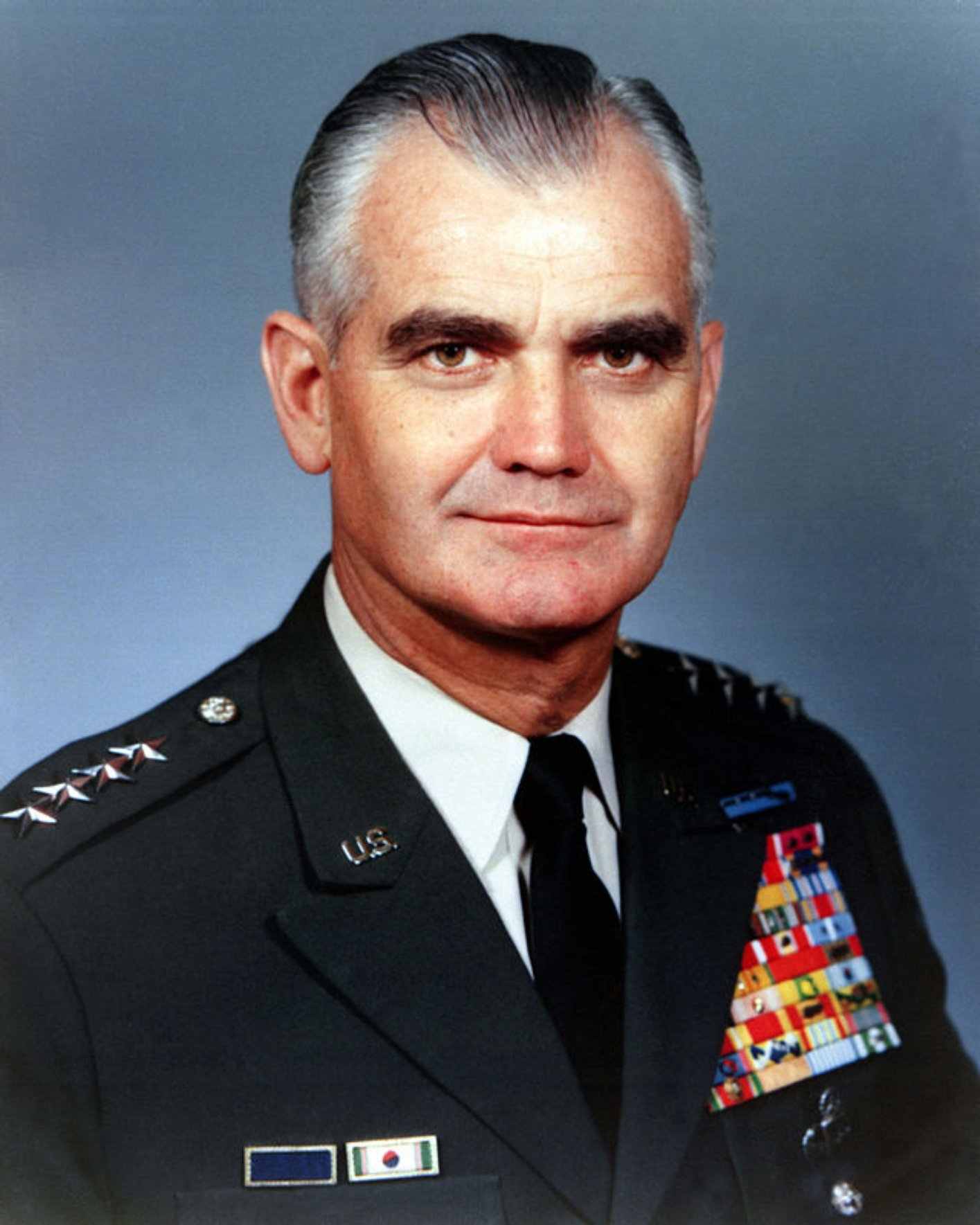

Over the next few years, the American military commitment to South Vietnam grew dramatically, and the war effort became both deeper and more complex. The strategy included parallel efforts to strengthen the economic and political foundations of the South Vietnamese regime, to root out the Viet Cong guerrilla insurgency in the south, combat the more conventional North Vietnamese Army (NVA) near the Demilitarized Zone between north and south, and bomb military and industrial targets in North Vietnam itself. In public, American military officials and members of the Johnson administration stressed their tactical successes and offered rosy predictions; speaking before the National Press Club in November 1967, General Westmoreland claimed, “I have never been more encouraged in the four years that I have been in Vietnam. We are making real progress…I am absolutely certain that whereas in 1965 the enemy was winning, today he is certainly losing.” (New York Times, November 22, 1967).

At the same time, the government worked to conceal from the American public their own doubts and the grim realities of war. Reflecting on the willful public optimism of American officials at the time, Colonel Harry G. Summers concluded, “We in the military knew better, but through fear of reinforcing the basic antimilitarism of the American people we tended to keep this knowledge to ourselves and downplayed battlefield realities . . . We had concealed from the American people the true nature of the war.” (Summers, 63).

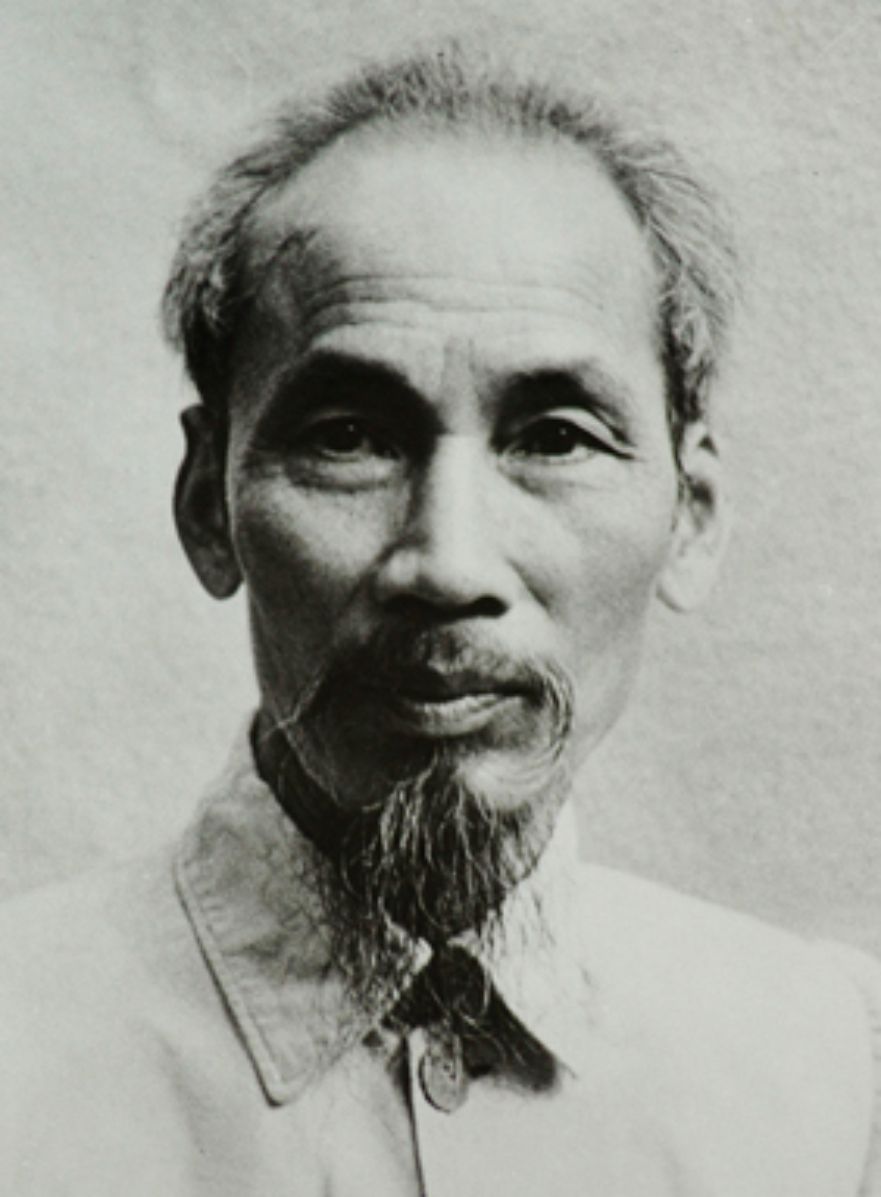

The seeds of Operation Rolling Thunder, America’s elaborately constrained air war against North Vietnam, appeared almost from the first moment that the USA inherited the conflict from the French. The half-communist, half-nationalist Viet Minh rebels of Ho Chi Minh evicted the French in 1954, but not before the latter partially created an anticommunist state, South Vietnam, in the lower half of the nation. Home to many Vietnamese who stood to lose property and potentially their lives in the event of the country’s reunification, the new state struggled with both Viet Cong guerrillas supplied by the north and its own internal corruption and factionalism. Many thousands of North Vietnamese fled there to escape Ho Chi Minh’s repression and occasional mass executions as well.

The United States, attempting to maintain its status as leader and defender of the non-communist world, gradually offered more and more support to South Vietnam’s leaders in Saigon, and direct military intervention became inevitable after the famous Gulf of Tonkin Incident, which also greatly influenced Operation Rolling Thunder. The actual incident consisted of a skirmish between three North Vietnamese torpedo boats, which managed to put exactly one machine-gun bullet hole in an American vessel, and a followup in which spooked American gunners fired at phantasmal radar image on a night of severe storm. These false images, caused by meteorological conditions, later received the sobriquet “Gulf of Tonkin ghosts.”

US Navy (USN) destroyer USS Maddox fired its weaponry at these fleeting signals, as did other supporting vessels and aircraft, but Squadron Commander James Stockdale of VF-51, piloting a Vought F-8 Crusader air superiority fighter in support of the American craft, saw no signs of the North Vietnamese: “When the destroyers were convinced they had some battle action going, I zigged and zagged and fired where they fired unless it looked like I might get caught in their shot patterns or unless they had told me to fire somewhere else. The edges of the black hole I was flying in were still periodically lit by flashes of lightning—but no wakes or dark shapes other than those of the destroyers were ever visible to me.” (Stockdale, 1985, 17).

President Johnson’s response to this incident provided a sort of blueprint and preview on which he eventually based the whole of Operation Rolling Thunder. Operation Pierce Arrow saw American airmen sent to strike targets in North Vietnam in response to the action – both real and imaginary – in the Gulf of Tonkin. Washington gave these pilots very limited targets and very specific instructions on how to attack them, the idea being to show the North Vietnamese that America “meant business,” theoretically prompting them to back down and come to the negotiating table.

Predictably, the lack of resolve showed by the strictly limited operation failed to change the North’s policies in the slightest. Both characteristics – Johnson’s faith in the power of highly circumscribed operations and North Vietnamese political indifference to them – would appear throughout Operation Rolling Thunder.

Faced with such a determined opponent, skilled in asymmetrical warfare and enjoying considerable popular support, the Americans would ultimately choose to fight a war of attrition. While the Americans did employ strategic hamlets, pacification programs, and other kinetic counterinsurgency operations, they largely relied on a massive advantage in firepower to overwhelm and grind down the Viet Cong and NVA in South Vietnam. The goal was simple: to reach a “crossover point” at which communist fighters were being killed more quickly than they could be replaced. American ground forces would lure the enemy into the open, where they would be destroyed by a combination of artillery and air strikes.

Naturally, if American soldiers on the ground often had trouble distinguishing combatants from civilians, B-52 bombers flying at up to 30,000 feet were wholly indiscriminate when targeting entire villages. By the end of 1966, American bombers and fighter-bombers in Vietnam dropped about 825 tons of explosive every day, more than all the bombs dropped on Europe during World War II. As Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara wrote to President Johnson in May of 1967, “The picture of the world’s greatest superpower killing or seriously injuring 1,000 noncombatants a week, while trying to pound a tiny backward nation into submission on an issue whose merits are hotly disputed, is not a pretty one.” (Sheehan, 685).

Operation Rolling Thunder: The History of the American Bombardment of North Vietnam at the Start of the Vietnam War chronicles one of the most controversial campaigns of the war, and the effects it had on both sides. Along with pictures of important people, places, and events, you will learn about Operation Rolling Thunder like never before.

Operation Rolling Thunder: The History of the American Bombardment of North Vietnam at the Start of the Vietnam War

The Evolution of Rolling Thunder

America’s Pilot Rescue Program

Free Books by Charles River Editors

Discounted Books by Charles River Editors

The Start of the Vietnam War

“The last thing I wanted to do was to be a wartime President.” – Lyndon B. Johnson

By the start of Operation Rolling Thunder, the United States had been heavily invested in opposing Vietnamese communism for the better part of two decades, and with the benefit of hindsight, the American war effort that metastasized there throughout the 1960s may seem like a grievous error and a needless waste of blood and treasure on an unwinnable and strategically insignificant civil conflict in a distant, culturally alien land. Indeed, it is still difficult for Americans today to comprehend how it was that their leaders determined such a course was in the national interest. Thus, it is essential at the outset to inquire how it was that a succession of elite American politicians, bureaucrats, and military officers managed, often despite their own inherent skepticism, to convince both themselves and the public that a communist Vietnam would constitute a grave threat to America’s security.

Vietnam’s first modern revolution came in the months of violence, famine, and chaos that succeeded World War II in Asia. Along with present-day Laos and Cambodia, the country had been a French colony since the late 19th century, but more recently, at the outset of World War II, the entire region had been occupied by the Japanese. Despite the pan-Asian anti-colonialism they publicly espoused, Japan did little to alter the basic structures of political and economic control the French had erected.

When Japan surrendered and relinquished all claim to its overseas empire, spontaneous uprisings occurred in Hanoi, Hue, and other Vietnamese cities. These were seized upon by the Vietnam Independence League (or Vietminh) and its iconic leader Ho Chi Minh, who declared an independent Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) on September 2, 1945. France, which had reoccupied most of the country by early 1946, agreed in theory to grant the DRV limited autonomy. However, when the sharp limits of that autonomy became apparent, the Vietminh took up arms. By the end of 1946, in the first instance of what would become a longstanding pattern, the French managed to retain control of the cities while the rebels held sway in the countryside.

Ho Chi Minh

From the outset, Ho hoped to avoid conflict with the United States. He was a deeply committed Communist and dedicated to class warfare and social revolution, but at the same time, he was also a steadfast Vietnamese nationalist who remained wary of becoming a puppet of the Soviet Union or the People’s Republic of China. Indeed, Ho’s very real popularity throughout the country rested to no small extent on his ability to tap into a centuries-old popular tradition of national resistance against powerful foreign hegemons, a tradition originally directed against imperial China. As such, he made early advances to Washington, even deliberately echoing the American Declaration of Independence in his own declaration of Vietnamese independence.

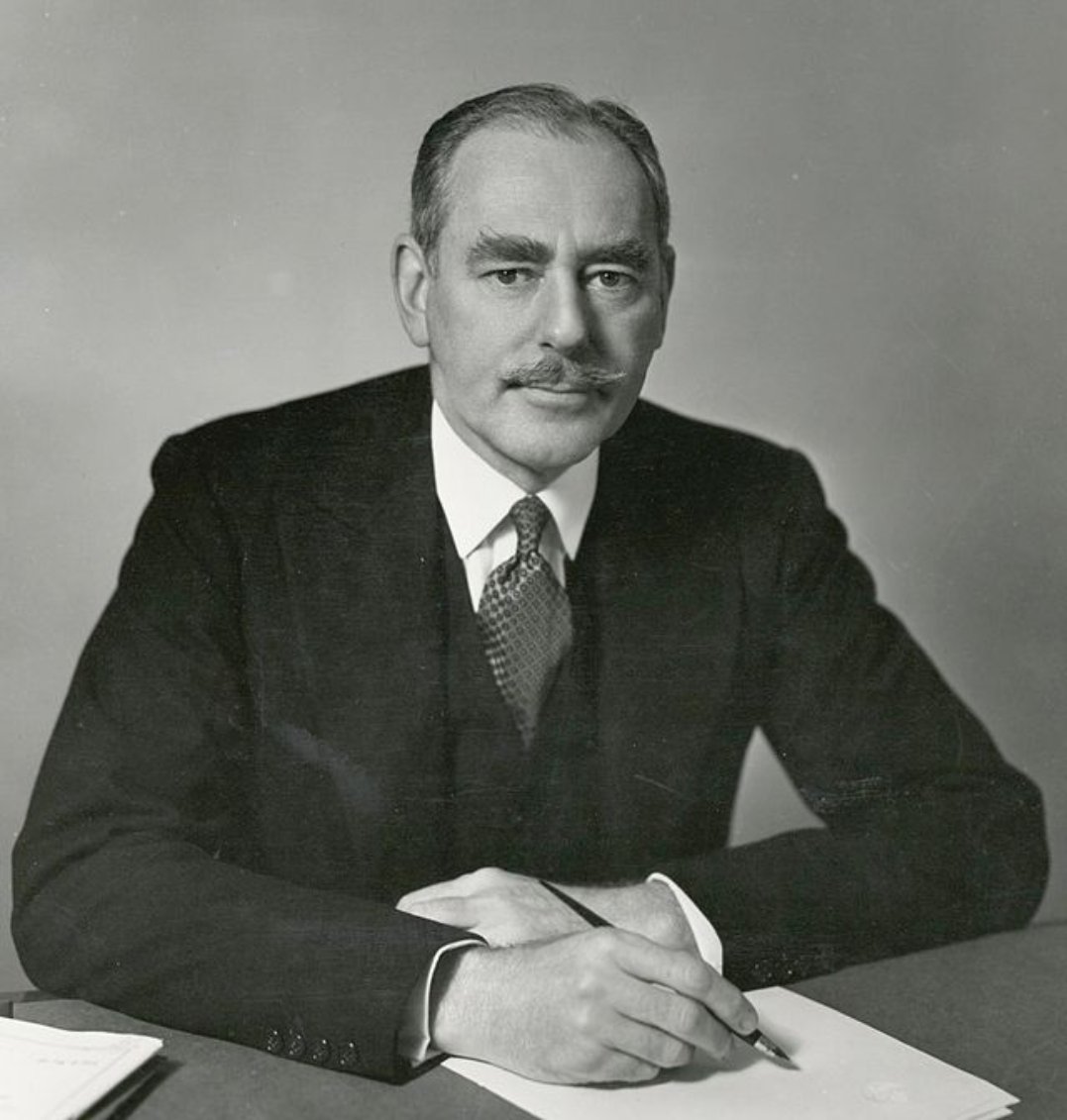

Under different circumstances, Americans might not have objected much to a communist but independent DRV. The Roosevelt and Truman administrations had trumpeted national independence in Asia and exhibited almost nothing but contempt for French colonial rule. However, as Cold War tensions rose, and as the Soviet Union and (after 1949) Communist China increased their material and rhetorical support for the Vietminh cause, such subtle gradations quickly faded. Considering the matter in May 1949, Secretary of State Dean Acheson asserted that the question of whether Ho was “as much nationalist as Commie is irrelevant. All Stalinists in colonial areas are nationalists . . . Once in power their objective necessarily becomes subordination [of the] state to Commie purpose.” (Young, 20 – 23).

Acheson

As a result, in 1950, the United States recognized the new puppet government France had established under the emperor Bao Dai, and by 1953 American financial aid funded fully 60% of France’s counterinsurgency effort. When that effort finally collapsed in 1954, an international conference at Geneva agreed to divide Vietnam at the 17th parallel into a communist DRV in the north and an American-backed Republic of Vietnam in the south. Between 1955 and 1961, South Vietnam and its new president, Ngo Dinh Diem, received more than $1 billion in American aid. Even so, Diem proved unable to consolidate support for his regime, and by 1961 he faced a growing insurgency in the Viet Cong (VC), a coalition of local guerrilla groups supported and directed by North Vietnam.

Diem

Bao Dai

As Diem and (after a 1963 coup) his successors teetered on the brink of disaster, American politicians and military officers grappled with the difficult question of how much they were willing to sacrifice to support an ally. In 1961, President Kennedy resisted a push to mount air strikes, but he agreed to send increased financial aid to South Vietnam, along with hundreds (and eventually thousands) of American “military advisors.”

The summer of 1964, which would normally be used to prepare for reelection, was a busy time for Lyndon B. Johnson’s Administration. His attempts to steamroll ahead on domestic policy legislation were quickly sideswiped by a surprising foreign policy event in the Gulf of Tonkin. In 1964, the USS Maddox was an intelligence-gathering naval ship stationed off the coast of North Vietnam for the purpose of gathering information about the ongoing conflict between North Vietnam and South Vietnam. The borders between North and South, however, were in dispute, and the United States was less up to date on changes in these borders than the two belligerents. In the process, the USS Maddox accidentally crossed over into North Vietnamese shores, and when the ship was sighted by North Vietnamese naval units, they attacked the Maddox on August 2, 1964.

Though no Americans were hurt, naval crews were on heightened alert as the Maddox retreated to South Vietnam, where it was met by the USS Turner Joy. Two days later, the Maddox and Turner Joy, both with crews already on edge as a result of the events of August 2, were certain they were being followed by hostile North Vietnamese boats, and both fired at targets popping up on their radar.

After this second encounter, Johnson gave a speech over radio to the American people shortly before midnight on August 4th. He told of attacks on the high seas, suggesting the events occurred in international waters, and vowed the nation would be prepared for its own defense and the defense of the South Vietnamese. Johnson thus had the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution drafted, which gave the right of military preparedness to the President without Congressional approval. The resolution passed shortly thereafter, giving the President the authority to raise military units in Vietnam and engage in warfare as needed without any consent from Congress. Shortly thereafter, President Johnson approved air strikes against the North Vietnamese, and Congress approved military action with the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution.

Once upon a time, Johnson had claimed, “We are not about to send American boys 9 or 10 thousand miles away from home to do what Asian boys ought to be doing for themselves.” By the end of the year, however, over 16,000 Americans were stationed in South Vietnam. Regarding this about-face, Johnson would explain, “Just like the Alamo, somebody damn well needed to go to their aid. Well, by God, I'm going to Vietnam's aid!”

It would be years before the government revealed that the second encounter was no encounter at all. The government never figured out what the Maddox and Turner Joy were firing at that night, but there was no indication that it involved the North Vietnamese. Regardless, by 1965, under intense pressure from his advisors and with regular units of the NVA infiltrating into the south, President Lyndon Johnson reluctantly agreed to a bombing campaign, Operation Rolling Thunder, against North Vietnamese targets. He also agreed to a request from General William Westmoreland, the American military commander in South Vietnam, for the first American ground troops deployed to Vietnam: two battalions of Marines to guard the air bases.

Westmoreland

Years later, General Frederick Weyand speculated that the disingenuous pronouncements of officers and politicians, while instrumental in making the initial case for intervention, may have poisoned the well of long-term public support: “The American way of war is particularly violent, deadly and dreadful. We believe in using ‘things’—artillery, bombs, massive firepower—in order to conserve our soldiers’ lives. The enemy, on the other hand, made up for his lack of ‘things’ by expending men instead of machines, and he suffered enormous casualties. The army saw this happen in Korea, and we should have made the realities of war obvious to the American people before they witnessed it on their television screens. The army must make the price of involvement clear before we get involved.” (Summers, 68).

Whether greater openness from the outset might have translated into steadier national resolve in the long term is impossible to say, but it would almost certainly have punctured some of the dangerous illusions that young American soldiers brought with them to Vietnam.

Compared with their predecessors in World War II and Korea, the average American soldier in Vietnam was considerably younger and in many cases came from more marginal economic backgrounds. The average American soldier in World War II was 26, but in Vietnam, the average soldier was barely 19. In part, this was due to President Johnson’s refusal to mobilize the national reserves; concerned that calling up the National Guard would spook the public and possibly antagonize the Russians or Chinese, Johnson relied on the draft to fill the ranks of the military. Moreover, given the numerous Selective Service deferments available for attending college, being married, holding a defense-related job, or serving in the National Guard, the burden of the draft fell overwhelmingly on the people from working class backgrounds. It also particularly affected African Americans.

The American military that these young draftees and enlistees joined had been forged in the crucible of World War II and were tempered by two decades of Cold War with the Soviet Union. In terms of its organization, equipment, training regimens, operational doctrines, and its very outlook, the American military was designed to fight a major conventional war against a similarly-constituted force, whether in Western Europe or among the plains of northeast Asia. As an organization, the military’s collective memories were of just such engagements at places like Midway, Normandy, Iwo Jima, Incheon, and the Battle of the Bulge. These campaigns predominately involved battles of infantry against infantry, tanks against tanks, and jet fighters against jet fighters. As boys, many of the young men who fought in Vietnam had played as soldiers, re-enacting the heroic tales of their fathers and grandfathers. The author Philip Caputo, who arrived in Vietnam as a young marine officer in 1965, recalled, “I saw myself charging up some distant beachhead, like John Wayne in Sands of Iwo Jima, and then coming home with medals on my chest.” (Caputo, 6).

Expecting a simple conflict of good against evil and knowing little to nothing of the local culture, American soldiers in their late teens and early 20s arrived in Vietnam and found a world of peril, privation, and moral ambiguity. Despairing of and for young rookie soldiers like Caputo, Bruce Lawler, a CIA case officer in South Vietnam, virtually exploded with rage: “How in hell can you put people like that into a war? How can you inject these types of guys into a situation that requires a tremendous amount of sophistication? You can’t. What happens is they start shooting at anything that moves because they don’t know. They’re scared. I mean, they’re out there getting shot at, and Christ, there’s somebody with eyes that are different from mine. And boom—it’s gone.” (Saltoli, 177).

Above all, success would be measured in terms of “body count;” Westmoreland’s staff estimated the crossover point at a kill ratio of 10 Viet Cong to every American. To that end, officers rewarded soldiers for confirmed kills, rules of engagement were unofficially loosened, and operations were sometimes planned solely to increase the body count. As Philip Caputo notes, the consequences of such a strategy for the outlook of the ordinary American soldier were as tragic as they were predictable: “General Westmoreland’s strategy of attrition also had an important effect on our behavior. Our mission was not to win terrain or seize positions, but simply to kill: to kill Communists and to kill as many of them as possible. Stack ‘em like cordwood. Victory was a high body count, defeat a low kill ratio, war a matter of arithmetic. The pressure on unit commanders to produce enemy corpses was intense, and they in turn communicated it to their troops . . . It is not surprising, therefore, that some men acquired a contempt for human life and a predilection for taking it.” (Caputo, xix).

Needless to say, this would inform how Operation Rolling Thunder was conducted.

The Evolution of Rolling Thunder

Operation Rolling Thunder began in early 1965, and it was hamstrung by some of the most restrictive rules of engagement ever imposed on a military force. The Joint Chiefs of Staff wanted to fight the war to win, smashing North Vietnam’s military capabilities by unleashing the full weight of America’s excellent air arm against Ho Chi Minh’s resources. President Lyndon Johnson, however, had other ideas. His policy revolved around fear of Soviet and Chinese involvement in the war, though a considerable body of intelligence suggested neither would likely intervene. The North Vietnamese accepted Chinese aid but viewed their large neighbor with extreme suspicion bordering on hostility. The Soviets, for their part, did not work well with the Chinese either, and they endured internal problems of their own at the time.

Nevertheless, Johnson disregarded the Joint Chiefs most of the time and relied almost exclusively on the plans and advice of Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara. David Halberstam, a reporter, summarized the latter’s involvement in Vietnam strategy pithily: “It is not a particularly happy chapter in his life; he did not serve himself or the country well; he was, there is no kinder or gentler word for it, a fool.” (Halberstam, 2001, 250).

McNamara

In the early stages of Operation Rolling Thunder, Washington chose all targets. Going far beyond this, however, Johnson and his civilian advisers eliminated practically all operational flexibility, so men with practically no military experience decided the exact timing of the strikes, the routes of approach and retreat, and all other details. The pilots assigned to the mission then had to adhere precisely to these prepackaged plans, or “frags,” as the men on the scene called them.

Despite these exacting limits, the men tasked with carrying out Rolling Thunder worked with courage, professionalism, and dedication. Johnson did not envision the missions as bringing about the defeat of the North by crippling its war-fighting capability; instead, he wanted the operation to demonstrate American resolve to the point where the North Vietnamese came to the negotiating table for a peaceful solution.

In this, Johnson proved either totally ignorant of his opponents’ psychology or deceived himself as to their nature. The North Vietnamese leadership and many of their soldiers evinced a mix of fierce nationalism and convinced communism, and Johnson’s half-measures simply convinced them of the weakness of American leadership and its lack of resolve to carry the war to a successful conclusion. Indeed, they proved willing to sacrifice large numbers of men and considerable amounts of materiel as long as they could continue working towards their overall goal. Their idea of peace consisted of the complete reunification of Vietnam under Ho Chi Minh’s dictatorship and, eventually, possible incorporation of parts of Laos and Cambodia into a small Vietnamese empire.

The slow start of Operation Rolling Thunder prompted one American commander to remark that the North Vietnamese probably did not even realize initially that they were under attack. This did not stem from Washington’s policies, but from poor weather conditions, along with South Vietnamese political turmoil.

President Johnson gave his approval for the operation on February 13, 1965, and the military initially scheduled the first strike for February 20, a week later. However, four operational launch dates fell by the wayside, and after “Rolling Thunder 1” through “Rolling Thunder 4” were canceled, Rolling Thunder 5 finally got off the ground on March 2, 1965. Though it lacked the full development and advanced weaponry of later operations, the mission represented almost a microcosm of the entire campaign. It involved targets and even approach routes chosen by Johnson and his advisors in Washington. US Navy (USN) aircraft participated, launched from the carriers offshore in the Gulf of Tonkin, as did VNAF (South Vietnamese) airplanes from land bases in the south of the country and US Air Force (USAF) jets operating from airstrips in Thailand and elsewhere.

Like so many other bombing missions to follow, this one involved a typical mix of the era’s combat aircraft. F-100 Super Sabres provided air cover and anti-flak support, while F-105 Thunderchiefs, known as “Thuds,” delivered bombs and rockets to the chosen targets. The VNAF deployed A-1 Skyraider propeller-driven aircraft, escorted by American jets, and the USN used F-4 Phantoms, Douglas A-4C Skyhawks, and other carrier-based aircraft. KC-135 tankers, nicknamed the “flying gas station,” provided midair refueling as needed. B-57 bombers also accompanied this first strike.

An A-4 Skyhawk

Rolling Thunder 5 concentrated on two targets: Quang Khe naval base and an ammunition depot at Xom Bang. Captain Robinson Risner led the mission against Xom Bang, and the Americans met vigorous anti-aircraft artillery (AAA) fire from the ground, along with fire from smaller weapons (including a few of the excellent but small-caliber World War II German machine guns). MG-34s appeared in the lineup from ancient Soviet stocks. Most weapons had a much a larger caliber, however, hurling streams of explosive shells into the sky to greet the incoming aircraft.

The North Vietnamese guns fired doggedly despite being strafed with rockets and 20mm cannons. One F-100 Super Sabre and one F-105 Thunderchief succumbed to this fire, and the pilots managed to eject without the broken arms or legs all too common when “bailing out” at the time. A helicopter rescue plucked Robert Baird to safety, while the Vietnamese captured the other downed flier, Hayden Lockhart.

The Xom Bang ammunition depot suffered annihilation, with numerous secondary explosions. The VNAF attack on Quang Khe naval base went as well as might be expected, damaging many of the buildings and possibly sinking three patrol boats at their berths.

The F-105 Thunderchief proved to be a good choice for Rolling Thunder bombing. It could only fly at subsonic speeds with its payload suspended below its fuselage. However, once it dropped its bombs or launched its missiles, it lost its aerodynamic burden and could accelerate to supersonic speeds, using a large afterburner. This meant a slower approach followed by a lightning-fast getaway if necessary. A pilot, Colonel Jack Broughton, later recounted the Thud’s unexpected success: “Struggling under a bombload that was huge for a fighter, the Thud waded into the thick of the fray and those not in the know coined the name Thud—with all its derogatory connotations. But gradually a startling fact became apparent—the Thud was getting to North Vietnam as nothing else could. Nobody could keep up with the Thud as it flew at high speed on the deck, at treetop level. Nobody could carry that load and penetrate those defenses except the Thud. Sure we lost a bundle of them and lost oh so many superior people along with the machines, but we were the only people doing the job, and we had been doing it from the start. There were other aircraft carrying other loads and performing other functions, pushing a lesser portion of explosives to the North, but it was the old Thud that day after day, every day, lunged into that mess, outdueled the opposition, put the bombs on the target and dashed back to strike again. Any other vehicle in anybody's Air Force today simply could not have done the job.” (Broughton, 2009, 21).

Rolling Thunder 5 had all the hallmarks of countless later missions, with large groups of mutually supporting aircraft from several different air services, strictly delimited targets, massive North Vietnamese AAA fire from quality, Soviet-supplied guns, air rescue of some shot-down pilots, and North Vietnamese capture of others.

The weather and bureaucratic confusion prevented the Americans from launching Rolling Thunder 6 until March 14, 1965, but despite the American commander’s quip that the North probably failed to perceive the USAF and PNAF had hostile intentions against them at all, the North Vietnamese understood clearly that bombing missions would continue and grow. Accordingly, the general in charge of the North’s air defenses, Nguyen Can Coi, worked with Ho Chi Minh’s government to secure as many anti-aircraft artillery (AAA) pieces and other anti-aircraft weapons as possible. These ranged from actual World War II German machine guns supplied by the Soviets from captured stockpiles – the excellent but small-caliber MG-34 and MG-42 designs – to 57mm and 90mm anti-aircraft artillery pieces manufactured in Russia or China. By April 1965, Hanoi’s stock of these armaments stood at approximately 1,000, supported by 26 radar units, both early warning and fire control. Additionally, the North Vietnamese sought and received pilot training for the MiG-15 and MiG-17 “Fresco” jet fighters in both China and the USSR. The Russians, happy to interfere with the Americans in any way possible, gave the North 36 MiG-17s outright, with no obligation to ever pay for them or return them. A second consignment soon followed.

A picture of a MiG-17 being shot down during the Vietnam War

Neither Ho Chi Minh nor Nguyen Can Coi rested on their laurels, and at North Vietnamese prompting, their larger Communist backers continued to ship a steady stream of AAA and supporting radar units to their protege. Many of these weapons arrived through the port city of Haiphong, a location kept off-limits by the Johnson administration until the later stages of Operation Rolling Thunder. By using ships flying the flag of the “neutral” USSR, the Russians and Chinese brazenly made AAA deliveries in daylight, even under the scrutiny of American reconnaissance jets, and the small patch of the planet’s surface occupied by North Vietnam soon bristled with the most powerful anti-aircraft defense network in history, exceeding even that of the Third Reich at the height of the World War II. The Vietnamese also benefited from an additional 20 years of weapons research, with their weapons possessing greater accuracy and range than anything built by any power during the early 1940s. They also possessed highly courageous gun crews who manned their armaments with determination despite the high chances of being wounded or killed during an American attack, should one occur.

By September 1965, the North Vietnamese deployed no less than 3,000 anti-aircraft artillery pieces. Taking a clever approach to tactics, they built more AAA emplacements than they had guns, which not only allowed them to reinforce defenses immediately as new artillery arrived from Russia rather than waiting for construction to finish, but also made it possible to shuffle guns between locations, making it more difficult for the Americans to predict exact defensive strength at any one place despite periodic photoreconnaissance.

The American use of prescribed approach routes also made the AAA crews’ task easier. Since the American aircraft, ordered by Washington, almost always approached a certain target along exactly the same vector, the Vietnamese crews sighted in along these routes to provide a lethal greeting to arriving American planes. That said, even with President Johnson breathing down their necks, the military managed to interject some flexibility into their planning whenever possible. They managed to persuade the bureaucrats to approve the use of different raid sides, as large “alpha strikes” containing dozens of aircraft often proved vulnerable to the North Vietnamese.

With so many jets attacking a single target, most had to “stack up” aloft in a holding pattern to wait their turn. This enabled the Vietnamese to simply fill the air with a cloud of bursting flak almost certain to hit something. Accordingly, the Americans started to use smaller, more nimble strike forces, often with “air cover” considerably outnumbering the actual strike jets or bombers. These forces could hit fast, do high levels of damage in many instances, and then leave just as quickly without the “aerial traffic jam” that made such a juicy target for Ho’s gunners.

Initially, Johnson only allowed missions between the 17th Parallel – the demilitarized border between North Vietnam and South Vietnam – and the 20th Parallel. Only about 200 miles of territory fell within this span, and it contained almost none of Hanoi’s important MiG bases, storage and stockpile facilities, industrial capacity, or significant military bases.

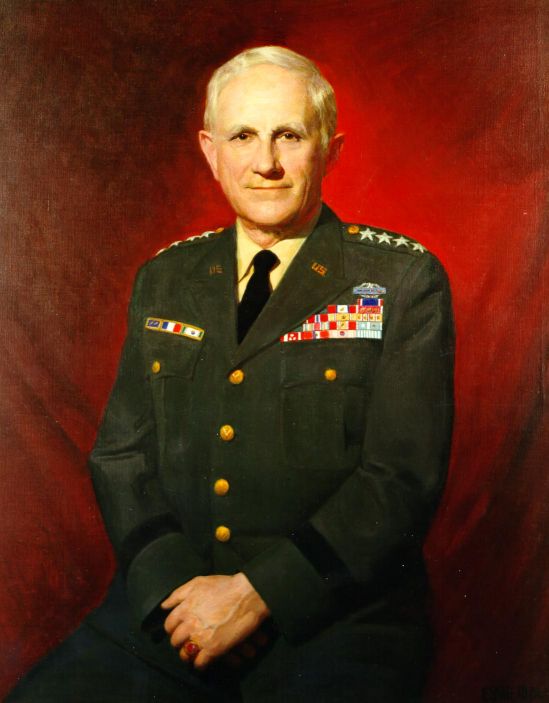

Eventually, Army Chief of Staff Harold Johnson managed to extract a number of important concessions from McNamara when McNamara visited Vietnam shortly after the launch of Rolling Thunder. These included the ability of the American forces on the scene to choose their own time to carry out their missions, though targets still required Washington’s approval. The Secretary of Defense also waived the absurd requirement to include VNAF aircraft in every mission, while adding bridges used for military supply traffic to the list of acceptable targets.

Johnson

On April 4, the Americans struck and destroyed a number of bridges, only failing to bring down the extremely sturdy Thanh Hóa Bridge, known as the Dragon’s Jaw. Just a day later, Operation Blue Tree reconnaissance aircraft saw and photographed a surface-to-air missile (SAM) site under construction. Though the news received top priority in transmission up the chain of command to the White House, the Johnson administration dismissed the information outright. Johnson and his advisors claimed that the site represented merely symbolic help from the Soviets, who would never provide the expensive, powerful missiles to the North Vietnamese. The president also forbade attacks on the SAM site (and indeed on all of the North’s construction sites) for fear of killing foreign advisors and leading to intervention from the major Communist powers.

Despite the political confidence that the North would never receive actual SAMs, the Russians had already shipped a number of the two-stage, Mach 3.5 missiles to the country. All supporting equipment, including their targeting radar, had already arrived. The so-called SA-2 Guideline – known to the Soviets as the S-75 Dvina, named for a Russian river – represented recent Soviet anti-aircraft missile technology at the time. One such weapon brought down Gary Powers’ U-2 Lockheed U-2 Dragon Lady reconnaissance aircraft in 1960.

As the number of SAM sites increased rapidly in the summer of 1965, the Johnson administration acknowledged their existence and debated what to do about them. A CIA report on June 30, 1965 recommended direct action against them: “[I]f we increase the pressure on NVN as visualized, one of the quickest ways to signal our serious intent as well as protect our attacking forces would be to destroy the SAM sites and major airfields. While a major Chinese and/or Soviet response cannot be totally ruled out, the risk will not necessarily be increased by pressing our limited-objective attacks on NVN.”

Johnson, though he could not know it, guessed correctly that some of the SAM sites harbored Soviet military personnel. However, the USSR viewed these men as a way to increase the effectiveness of the sites of their North Vietnamese proxies, not a trigger for direct war with the United States if the Americans killed them during an airstrike.

The president authorized strikes against SAM sites after an S-75 Dvina shot down an F-4 Phantom on July 24. Expecting retaliation, the Soviets and Vietnamese put the SAM sites on high alert, and sure enough, on July 27, 1965, the Americans launched a mission against a cluster of SAM sites. The American pilots encountered far deadlier fire than the AAA could deploy even at its heaviest, as Sergeant N. Kolesnik later recounted to a Soviet military newspaper: “The most impressive moment was when the planes were downed. All of a sudden through this dark shroud [of clouds] an object you couldn't even see before comes down in a blaze of shattered pieces. We got four planes with three rockets, yes, four planes. The fourth plane was hit by rocket fragments.” (Clines, 1989, Web).

With more than 5,900 sorties in the month of July 1965 alone, the Americans urgently required a countermeasure to the SAM threat. One tactic called for missions to only go ahead with a cloud ceiling of 8,000 feet or higher, giving the pilots time to spot the incoming missiles and evade them if possible.

A more solid solution arrived in the form of “Wild Weasels,” two-seat fighters such as F-100F Super Sabres, and later F-105Fs, equipped with AGM-45 and AGM-78 anti-radiation missiles. These missiles locked onto the SAM radar and homed in on it rapidly. Sometimes the missiles reached the SAM site and annihilated it. More often, the SAM radar operators switched off their radar to survive. This had the effect of denying airborne S-75 Dvina rockets their guidance, causing them to fly off harmlessly and crash after exhausting their fuel. Wild Weasels and their USN equivalent, “Iron Hand,” quickly cut SAM effectiveness by half.

Picture of an F-100D firing rockets during the war

The USAF also deployed EB-66 Destroyer light bombers, while the Navy used EA-3 Skywarrior strategic bombers, packed with electronic warfare equipment to scramble North Vietnamese radio traffic and radar. Major missions now required extremely complex coordination, though the Americans proved up to the task.

Later in 1965, McNamara decided to divert many air assets to supporting a bigger American ground presence in South Vietnam. Admiral U.S.G. Sharp noted, “Our Rolling Thunder bombing program against North Vietnam got off to a painfully slow start and inched along in the most gradual increase in intensity. At the same time we decided to employ additional ground forces in South Vietnam and use them in active combat operations against the enemy. Despite [CIA Director] John McCone’s perceptive warning vis-à-vis the implications of deploying those ground forces without making full use of our air power against the north, Secretary McNamara chose to do exactly that, i.e., to downgrade the U.S. air effort in North Vietnam and to concentrate on air and ground action in the south. This fateful decision contributed to our ultimate loss of South Vietnam.” (Emerson, 2018, 41).

Initially, however, the Americans managed to maintain some pressure on North Vietnam by moving more aircraft carriers to the Gulf of Tonkin. The military also continued to work out more details for their Rolling Thunder operations. Planners divided North Vietnam into seven different “route packs” or “route packages,” some assigned to the USAF and others to the USN. Expanded geographical extent and a larger target list, including opening certain types of military equipment to “attacks of opportunity,” improved Rolling Thunder’s effectiveness to some degree in late 1965.

This effectiveness ceased when President Johnson declared a bombing halt beginning on December 24. Originally planned to last for 30 days, the halt ended up enduring for 37 days, as the Johnson administration continued to mistakenly believe the North would take this chance to negotiate for an end to the war. The determination of Hanoi predictably remained unshaken, and Johnson’s overtures suggested weakness, not strength, to Ho Chi Minh and his cabinet. During the bombing halt, the North Vietnamese busied themselves repairing damage, moving larger amounts of supplies south to assist the Viet Cong, and digging in more AAA and SAM sites to extend a less than cordial welcome to the Americans when they eventually returned.

The Dragon’s Jaw

Bearing the ominous name of the Dragon’s Jaw, the Thanh Hóa Bridge became a bone of lethal contention between the Americans and North Vietnamese during the first summer of Rolling Thunder. Among its other sobriquets, the extreme difficulty of damaging the bridge and the danger of the missions earned it the title of the “Thanh Whore” among American pilots. The 540-foot-long bridge crossed the wide Song Ma River, at a point where 50-foot cliffs flanked the watercourse. This structure provided a key rail link in North Vietnam, carrying as much as 3,000 tons of cargo per day at its busiest.

A picture of the bridge during the war

Modern bridge-building had been introduced to Vietnam by the French during their colonial period. They first constructed a bridge at the site of the Dragon’s Jaw for the same purpose, that of carrying a railroad connection across a major Indochinese river. The French engineers completed the structure in 1904, during the administration of Paul Doumer.

The Viet Minh began serious efforts to evict the foreigners during the opportunity offered by World War II, and during one of their operations, they destroyed the bridge as a way of crippling the occupiers’ logistics. The method they apparently adopted, like something out of a pulp adventure novel, consisted of packing two unmanned locomotives with dynamite and stolen military explosives, jamming their controls wide open, and sending them careening into each other from opposite sides of the bridge. The explosion at the center sent the span crashing ruinously into the muddy water below.

After the French withdrew from Vietnam in 1954, the Vietnamese began a reconstruction and modernization program, using the skills and techniques learned from the Europeans. An engineer named Nguyen Dinh Doan led the bridge-building effort at the vital crossing and raised a massively “overbuilt” steel structure across the river, using tremendous metal beams and towering, gigantically thick piers of reinforced concrete. The bridge opened in 1964, with the lean, sly, ruthless Ho Chi Minh himself cutting the ribbon.

Just one year after its grand opening, the Americans casually slated the Dragon’s Jaw for destruction as part of Rolling Thunder. Unaware of its fortress-like construction, the American commanders assigned it as one of three bridge targets during expanded bombing in early April 1965. The mission called for attacks on Hong Hoi, Dong Phuong Thuong, and the Dragon’s Jaw.

Carrier-based USN aircraft struck Dong Phuong Thuong on the Song Len River on April 3, 1965 after a delay caused by bad weather and lack of sufficient aerial refueling aircraft in supporting positions. Vought F-8 Crusader air superiority fighters hammered the anti-aircraft artillery (AAA) positions dug in around the Dong Phuong Thuong bridge with 20mm cannons and 2.75” rockets. Meanwhile, dozens of Douglas A-4C Skyhawk attack aircraft – also known as the “Bantam Bomber” and other unflattering nicknames – dropped 72 tons of ordnance on the bridge, collapsing its main span in addition to badly cratering its approaches. The Vietnamese shot down and captured one pilot.

The VNAF launched 20 A-1 Skyraiders fitted with both 250- and 500-pound bombs against Hong Hoi. Despite the relatively small force and low speeds offered by the piston-engine, propeller-driven A-1s, the South Vietnamese pulverized the Hong Hoi bridge. Made of wood, it had almost no resistance to either direct hits or bomb shockwaves.

The Dragon’s Jaw proved a different matter thanks to its exceedingly burly construction. The Air Force assigned Lieutenant Commander Robinson “Robbie” Risner the task of leading the 67th Fighter Squadron out of Korat, Thailand against the Dragon’s Jaw. A highly experienced pilot who had participated in World War II and Korea, Risner had already been shot down on March 22, but the Navy managed to rescue him after he ditched in the sea and he returned to active flying immediately. On April 3, 46 F-105 Thuds launched out of Thailand under Risner’s direct command, refueled along the way by ten KC-135 Stratotankers. A second group of aircraft launched from South Vietnam, including 21 F-100 Super Sabres tasked with suppressing AAA positions, 14 F-100s to form a combat air patrol (CAP) screen against enemy MiGs, and a pair of McDonnell RF-101C Voodoo jets to provide photo recon.

“Alpha Nine,” as the Air Force named the strike, arrived punctually at 2:00 p.m. over the 50-foot deep river gorge spanned by the Dragon’s Jaw. A light haze over the tropical landscape created a visibility range of 5-7 miles near the bridge, under a sunny sky. The F-100 Super Sabres struck first, pounding the Vietnamese AAA emplacements with rockets and cannon fire. Nevertheless, the Vietnamese raised a furious curtain of gunfire as the F-105Ds moved in to strike the bridge. Due to the nearly obsolete weaponry they carried, each aircraft had to dive at the bridge in turn, creating a revolving door effect in which pilots dived, attacked, pulled out, and rejoined the aerial swarm orbiting overhead to await their turn for a second run.

The pilots launched their 250-pound warhead AGM-12 Bullpup missiles at the bridge first. Though many scored direct hits along the whole length of the structure where it crossed the broad river, the bridge did not fall. Just as stubborn as its architect intended, the Dragon’s Jaw weathered the Bullpup hits with nothing worse than minor damage and blackened paint. As USAF Major A.J.C. Lavalle put it, “it became all too obvious that firing Bullpups at the Dragon was about as effective as shooting B-B pellets at a Sherman tank.”

Next, the Americans tried their 750-pound bombs. Poorly fused with World War II fuses, the bombs tended to detonate either too soon or too late to hit the bridge with their full blast. Navigating a sky full of exploding anti-aircraft shells, the USAF pilots nevertheless did their best, though it proved insufficient to bring down the Dragon’s Jaw. Captain Ivy McCoy of the 67th summed up their frustration with his own bombing run description: “When I rolled in the bridge was still standing and I felt, ‘Here is your chance.’ I put a perfect stick of eight 750s across the bridge. As I circled around, climbing out, all I could see was water and smoke. But as it cleared, the damn bridge was still standing.” (Coonts, 2019, 32).

A North Vietnamese AAA shell struck and tore apart 1st Lieutenant George Smith’s F-100D, killing him, and as the American raiders streamed away, leaving the Dragon’s Jaw blackened but intact, the two RF-101C Voodoos moved in to photograph the results. The North’s gunners, knowing American habits well, expected them and met them with a sky full of Soviet-made flak.

Captain Hershel “Scotty” Morgan’s Voodoo took a hit from flak shell shrapnel. Morgan turned south immediately, but his aircraft began losing altitude. 75 miles south of the bridge, near Vinh, he ejected. No rescue reached him in time and the NVA took him prisoner, to remain in captivity for seven years. Risner’s aircraft suffered a fuel tank hit, but he reached Da Nang and safety below the 17th Parallel.

The surviving Voodoo’s photos confirmed what the pilots already reported: the Dragon’s Jaw had survived Alpha Nine. In fact, traffic across it resumed after a few hours of cleanup in the afternoon. Accordingly, the USAF immediately planned another strike for the following day, April 4, 1965.

Risner commanded again, but this time, the F-105 Thuds would carry only 750-pound bombs, with none of the feeble AGM-12 Bullpup missiles in their loadout. 48 F-105s and 20 F-100s participated in the raid on the Dragon’s Jaw. This time, the Americans made no effort to suppress the powerfully dug-in NVA AAA positions.

As the first Thunderchief dove in through low scud and haze, delivered its bombs, and climbed out, one of the 37mm shells in the fusillade greeting the Americans found its mark in the fuselage. Captain Carlysle “Smitty” Harris tried to escape the area, but the damage forced him to eject into a rice paddy, where the North Vietnamese captured him. The North Vietnamese air force also put in its first appearance in the form of four MiG-17s led by Tran Huy Han, which successfully shot down two F-105s, killing their pilots. Appearing suddenly out of the clouds, the sleek MiGs riddled the aircraft of James Magnusson and Frank Bennett with cannon fire. The Viet pilots then flashed off into the haze, eluding retaliation. Both American pilots made it to the Gulf of Tonkin, but Magnusson simply vanished, while Bennett died when his parachute deployed too late and he slammed into the water at fatal speed. Walter Draeger, flying an A-1 Skyraider, also perished when shot down by AAA while searching a possible Magnusson crash site just offshore, within range of NVA shore batteries.

300 bomb hits on the second day of attacks on the Dragon’s Jaw had also failed to destroy it. The North claimed a “Great Spring Victory,” giving medals to the 228th Air Defense Artillery Regiment’s crews. While some engineers commenced repairs, others threw pontoon bridges across the waterway both upstream and downstream to permit at least part of the military supply traffic to continue.

The Thanh Hóa Bridge rapidly assumed symbolic value beyond its already high logistical value to both sides. The Vietnamese reinforced its defenses, while the Americans planned additional bombing missions.

On May 7th, the 355th Tactical Fighter Wing and other USAF units struck the Dragon’s Jaw for a third time using 750-pound bombs. During the first strike, the NVA gunners badly damaged the F-105 Thunderchief of Major Robert Lambert. Lambert reached the ocean before ejecting. Other F-105s harried the junks, swarming with North Vietnamese, who tried to reach Lambert’s position, sinking several with cannon fire and driving the others back. An HU-16 Albatross flown by Captain Richard Reichardt managed to land and rescue Lambert, unharmed other than his soaking in the ocean.

The 350 bombs dropped on May 7th did little to harm the Dragon’s Jaw, so bombing missions continued periodically against it. The USAF learned their lesson, however. Noting the resilience of the bridge and the vulnerability of the aircraft braving a tornado of flak following one another in a long “daisy chain,” the May 31st bombing involved just four F-105 Thuds, which struck quickly and fled.

By this time, the North Vietnamese had several permanent repair crews assigned to the Dragon’s Jaw, now a symbol of national pride. The Americans side, upped the ante by arming their four-aircraft bombing squadrons with M118 bombs, weighing 3,049 pounds with a 2,000-pound explosive payload. USAF bombers dropped M118s on the Thanh Hóa Bridge on July 28th and again on August 2nd, but both strikes failed to destroy the span. The North Vietnamese shot down and captured Captain Robert Daughtrey near the bridge.

While the planners initially assigned the Thanh Hóa Bridge as an exclusive USAF target, its toughness soon prompted them to order USN carrier-based aircraft strikes against it. The first, on June 17th, involved A-4 Skyhawk “Bantam Bombers” from USS Bonhomme Richard and USS Midway, shepherded by F-4 Phantoms. The attack on the bridge itself proved as futile as any of the USAF’s efforts, but the F-4 Phantoms scored the first American victory over the VPAF’s elusive MiGs during this mission. Meeting a flight of four MiG-17s head-on, the F-4 crews launched their Sparrow missiles at ranges theoretically too short to be effective. Reality trumped theory when the missiles struck and destroyed two of the MiGs outright. The VPAF pilots parachuted to safety, but a third MiG, maneuvering violently to escape the blast, plowed directly into a nearby ridge. Its pilot, Le Trong Long, died in the crash. The fourth MiG, piloted by squadron leader Lam Van Lic, maneuvered desperately as the Americans shot past close enough to see him clearly in his cockpit fighting his aircraft’s controls, and he ultimately managed to escape.

The Dragon’s Jaw continued to be the epicenter of ongoing bombing missions and powerful North Vietnamese air defense action. Sometimes the Americans succeeded in stopping traffic across the bridge for a few hours, a few days, or even a few weeks, but the main structure seemed indestructible and the North Vietnamese worked tirelessly to restore this emblem of their national defiance after each strike.

The local geography of the Thanh Hóa Bridge also meant that fog, rain, or cloud often shrouded it, making some strike missions more difficult or forcing their cancellation altogether. The Americans tried night attacks featuring radar bombing with no better success, though perhaps slightly more safety from North Vietnamese flak.

So many craters dotted the approaches to the Dragon’s Jaw that the Americans soon dubbed it “the Valley of the Moon.” Unable to bring down the extremely tough span, the USAF and USN turned to smashing Railroad #4, which crossed the Thanh Hóa south of the bridge as soon as weather improved in 1966. By June, the bombing made 13 major gaps in the railroad tracks, trapping hundreds of train cars in the area.

By this time, the Americans considered downing the bridge a matter of honor rather than mere practicality. Accordingly, they launched Operation Carolina Moon. This bizarre plan combined American technical know-how and manufacturing capacity to make special “mines” specifically to destroy the Dragon’s Jaw. Each of the mines consisted of a tremendous disc, 8 feet wide and 30 inches tall. Only the Atomic Energy Commission had the fabrication machinery needed to build the huge steel shell of each mine. Once built, scientists and engineers at Eglin Air Force Base in Florida, part of the base’s world-class Armament Development Laboratory, filled the interior of each mine with a complex array of chemical explosives. The engineers designed the weapon to deliver a 1-kiloton non-nuclear blast straight upwards.

Despite weighing 5,000 pounds apiece, the mines floated on the surface of water, as tested with 10 unarmed dummies dropped experimentally on the ocean off Florida by parachute. The Armament Development Laboratory built an additional 20 “live” Carolina Moon mines. These featured a sophisticated radar fuse in their upper surface which would cause them to explode when they floated underneath the Dragon’s Jaw. The radar could distinguish the size of overhead objects so it would not detonate prematurely when a bird or aircraft passed over it.

The Tactical Air Warfare Center (TAWC) at Nevada’s Nellis Air Force Base oversaw development of the plan. Their mission profile called for two C-130s to fly into an area upstream of the Dragon’s Jaw at altitudes of less than 500 feet, staying below most North Vietnamese radar. Hugging the terrain at dangerously low levels, the enormous C-130 Hercules transports would use parachute deployment to drop a total of 10 Carolina Moon mines onto the surface of the Song Ma. The gigantic mines would then float down the current and detonate one after another under the span, blowing it upward off its piers.

The TAWC picked two skilled aviators, Major Thomas Case and Major Richard Remers, to command the C-130s on this eccentric mission. Planning worked out the scheme in meticulous detail. The planners chose a 19-minute approach route offering the two C-130s maximum survival chances and slated the operation for night. Intelligence pieced together exact information on the Song Ma river miles upstream of the objective, ferreting out minute details of water depth, the location of sandbars, currents, and more. The crews received exhaustive training and practice runs under conditions of the utmost secrecy.

By late May 1966, the C-130s, their crews, and all 20 operational Carolina Moon mines arrived at Da Nang, ready to launch the mission. Shortly after midnight on May 30th, under a nearly full moon, Major Remers’ C-130 took off and flew north. The crew maintained strict radio silence and used no radar, navigating solely by landmarks picked out below by the brilliant moonlight. As the C-130 approached its objective over shimmering rice paddies and dense stretches of jungle, F-4 Phantoms launched a spectacular diversionary attack several miles downstream of the Dragon’s Jaw. Dropping bombs, firing missiles, and filling the air with flares, the jets made a spectacular light show designed to draw all North Vietnamese attention away from the Carolina Moon drop site.

Remers arrived over the river to find no AAA fire greeting him. With a quiet night sky overhead and the paddies slumbering below, the Hercules crew flew a mile closer to the Dragon’s Jaw. Here, alert soldiers of the 228th Air Defense Regiment opened fire on the engine noise audible in the sky above them. Still, the C-130 loadmasters deployed one parachute after another. The parachutes snatched the gigantic mines out over the rear ramps of the C-130s and slowed their descent as they fell towards the river below. With the five huge explosive discs dropped onto the river surface, the C-130s turned for home. Arriving safely back at Da Nang, the men launched a noisy, alcoholic celebration of their success.

Aerial reconnaissance soon threw a pall over their party, however. A pair of RF-101 Voodoo jets skimmed over the Dragon’s Jaw, taking a long series of photographs along the length of the river for several miles. In these photographs, the bridge appeared undamaged. No mines could be seen anywhere along the river’s length.

To the dismay of the C-130 crews, headquarters ordered Major Thomas Case to fly to Thanh Hóa and drop his consignment of five Carolina Moon mines on the night of May 31st. Case obeyed, despite the fact Remers’ raid had already put the North Vietnamese on the alert. After hours of argument with his superiors, the Major took off from Da Nang at 1:10 a.m.Piecing together later evidence, the C-130 reached the river and successfully deployed all five of its mines. However, flak struck the aircraft and Case attempted to fly to Laos to increase chances of rescue. The C-130 nosed down and plunged into remote, uninhabited jungle 25 miles west of the Dragon’s Jaw, killing all eight men aboard.

The Vietnamese issued strange, contradictory propaganda reports of soldiers with rifles on the bank detonating the mines with 7.62x39mm bullets, sampan crews somehow wrestling the gigantic, 5,000-pound steel discs out of the river to be examined and detonated on land, or beached and then exploded due to internal “self-destruct charges,” which did not exist in the form described. However, no trace of any of the mines has ever been produced.

Several years later, a captured North Vietnamese patrol boat crewman reported that the second string of bombs – those dropped by the crew of Thomas Case – all detonated under the bridge, launching fountaining blasts of fire and shrapnel around it, but that they failed to produce more than minor damage to the underside.

Perhaps the most probable explanation of the “disappearance” of the 10 Carolina Moon mine is that all 10 successfully deployed on the river. They floated under the Dragon’s Jaw, exploded, and failed to damage the incredibly tough construction 50 feet above them despite their awe-inspiring 1-kiloton conventional yield. This matches both the patrol boat crewman’s report and the total disappearance of the mines within a few hours of their use.

Bombing attacks on the Dragon’s Jaw in September 1966 managed to put the bridge out of service for weeks, but they did not even come close to bringing it down. In March 1967, the Navy tried out a new weapon called the Walleye Glide Bomb. The AGM-62, a precision-guided munition, used smart bomb television guidance technology to steer itself to the designed point of aim without further pilot input once released.

A trio of A-4C Skyhawk Bantam Bombers launched against the Thanh Hóa Bridge on March 12th, 1967. Their highly competent and aggressive leader, Homer Smith, selected three key girders to be the targets for their AGM-62 Walleyes. While their escort attacked the bridge defenses, the A-4Cs dived to deliver their glide bombs. Each AGM-62 struck with great precision within five feet of the point of aim, but the bridge apparently remained unfazed. The AGM-62 proved itself elsewhere by destroying numerous other bridges and installations. Only the strength of the Dragon’s Jaw’s construction baffled the exactly on target 850-pound warheads.

During the next six months, April-September, the Americans flew only 97 sorties in total against the bridge, approximately the same number as during the first two days of strikes against it in 1965. Extremely bad weather stopped attacks in October 1967, with no resumption until 1968.

A break in the weather on January 28th, 1968 allowed the Americans to launch a fresh mission against the Thanh Hóa Bridge. This time, 44 USN and USAF aircraft hammered the structure relentlessly over the course of nearly four hours. Though they succeeded in damaging some girders and smashed the actual railway tracks on the span, the main structure remained imposingly unharmed despite the Americans’ best efforts.

The monsoon closed in again and the air services postponed further operations. The launch of the Tet Offensive finally ended efforts against the Dragon’s Jaw for the remainder of Rolling Thunder. The Viet Cong attacked the Americans and South Vietnamese all across the country during the Tet holiday, and though they were smashed and defeated in detail, and nearly exterminated in many regions, the Viet Cong nevertheless won a tremendous propaganda victory. The American media, siding with the North Vietnamese, relentlessly portrayed the Tet Offensive as a stunning American defeat, the exact opposite of reality. This in turn put enough pressure on Johnson to call a bombing halt north of the 19th Parallel on March 31st, 1968, putting the Dragon’s Jaw off-limits to further Rolling Thunder raids.

While Richard Nixon committed to gradual American retreat from the war after his election, the Dragon’s Jaw ironically fell during his time as president, though not as part of the long-defunct Rolling Thunder. In 1972, the North Vietnamese launched their East Offensive, a surprise attack consisting of 150,000 men. Despite initial success, the South Vietnamese and Americans again successfully counterattacked and crushed the three-pronged offensive.

The offensive reopened air operations over North Vietnam, ultimately leading to the destruction of 106 bridges by June 1972, among numerous other targets. Dubbed Operation Freedom Dawn, the plan saw a strike against the Thanh Hóa Bridge on April 27th. F-4 Phantoms based in Laos pummeled the bridge with laser-guided bombs, or LGBs, along with more conventional munitions. Despite heavy cloud cover and fog, the Americans had the satisfaction of finally heavily damaging the bridge.

A follow-up mission on May 10th hit the bridge with 3,000-pound LGBs. At last, the Americans blasted the western span right off its piers and sent it crashing, shattered, burnt, and twisted, into the river below. The North Vietnamese did not even bother attempting to repair this catastrophic damage until after the end of the war.

Rolling Thunder Matures

With a cooperative array of aircraft types – strike aircraft, escort or air cover, midair refueling, electronic warfare and countermeasures Wild Weasels or Iron Hand, and search-and-rescue – now set up, and the efficiency offered by the Route Pack system to streamline planning, the Americans found themselves prepared to resume Rolling Thunder quickly after the end of Johnson’s bombing halt.

The Johnson administration initially reined in the air campaign in the North in early 1966. Only missions in Route Packs I, II, and III generally received approval, with a strict cap on the total number of sorties permitted weekly. The monsoon weather further cut into operational flexibility.

The pilots returning to North Vietnam now found themselves confronted by approximately 5,000 AAA pieces and 25 SAM battalions, along with much improved emplacements. The Americans also proved their willingness to escalate as much as their rules of engagement permitted. Massive B-52 bombers made their first attacks in North Vietnam, with authorization by the Joint Chiefs in early 1966.

By mid-1966, Rolling Thunder appeared to be fizzling out, but it received a boost when Johnson unexpectedly approved missions against the North’s petroleum processing and storage facilities. The targets, almost incredibly, included some in the previous off-limits cities of Hanoi and Haiphong. Thus, from late June to mid-July, the USAF and USN struck repeatedly at the North’s gas and oil infrastructure. Some of the raids ended with minimal damage, but others destroyed large quantities of fuel and the facilities holding them. Half of the North Vietnamese petroleum stores went up in columns of flame and choking black smoke within two weeks.

The North Vietnamese dispersed their storage far and wide to counteract this fresh phase of Rolling Thunder. A favorite trick consisted of putting the gasoline and oil in 55-gallon drums and storing thousands of these in and around the houses of small villages throughout the country. The Americans could not destroy these supplies, even if they learned of them, without killing large numbers of civilians, something they declined to do despite Hanoi’s strident propaganda to the contrary.

Later in 1966, MiG-21 jet fighters arrived in Vietnam from the Soviet Union, and these made a welcome augmentation for the VPAF’s pilots. MiG-17s, though immediately deadly in air-to-air encounters, ran out of ammunition in 5 seconds of continuous firing. Additionally, the design proved hideously poor, with fuselages occasionally imploding violently if the pilot allowed onboard fuel to fall below 50% – generally with lethal results for the pilot. The MiG-21 “Fishbed” – faster, better-armed, and lacking the fatal fuel tank design flaw – produced 13 North Vietnamese aces compared to the MiG-17’s three aces.

With monthly sorties rising to over 13,000 by the last days of 1966, Operation Rolling Thunder appeared to reach a new crescendo. Despite some targets being bombed 10, 20, or more times due to Washington’s orders, even longer after American bombs and missiles transformed them into a smear of rubble, the pilots managed to inflict considerable damage to bridges, depots, and transport. Meanwhile, aerial defenses around Hanoi and Haiphong proved stronger than anywhere else in North Vietnam, making these missions particularly risky. Escaping after the Vietnamese shot down an aircraft also represented a much larger difficulty. With more isolated targets, a pilot could often hide out in thickly forested hills, ravines, and other difficult terrain for hours or even a few days until rescue helicopters arrived. Bailing out over the major urban centers and the heavily developed land around them led to almost certain capture.

One pilot, Jack Broughton, vividly described the dangers of the aerial battlefield around the North Vietnamese capitol: “And the fourth air war was the big league. The true air war in the North. The desperate assault and parry over the frighteningly beautiful, green-carpeted mountains leading down into the flat delta of the Red River. The center of hell with Hanoi as its hub. The area that was defended with three times the force and vigor that protected Berlin during World War II. The home of the Sam and the Mig, the filthy orange-black barking 100-millimeter and 85-millimeter guns, the 57- and 37-millimeter gun batteries that spit like a snake and could rip you to shreds before you knew it, the staccato red-balled automatic weapons that stalked the straggler who strayed too low on pullout from a bomb run, and the backyard of the holders of rifles and pistols who lay on their backs and fired straight up at anyone foolish or unfortunate enough to stumble into view. This was the locale of Thud Ridge.” (Broughton, 2009, 33).

As the topography around Hanoi became better known, the Americans dubbed a long finger of raised land “Thud Ridge,” named for the Thud nickname of the Thunderchief. Thud Ridge assumed the guise of an important landmark used by pilots guiding themselves to their targets near the North Vietnamese capitol. The lakes near Hanoi became a spot where many downed pilots landed in an effort to hit the water, including John McCain.

Throughout 1966 and 1967, American aircraft and North Vietnamese SAM sites dueled fiercely. In 1966, the USAF lost 111 combat aircraft over the North, while the USN suffered lower casualties. In exchange, American pilots damaged or destroyed outright 77 SAM sites and 1,200 AAA emplacements, while dropping 200 million pounds of ordnance on targets north of the DMZ in the course of close to 80,000 sorties.

In 1966, the new MiG-21s along and the older MiG jet fighters of the VPAF pounced repeatedly on American aircraft. Though greatly outnumbered, the North Vietnamese pilots proved brave and determined. Using cloud and mist for camouflage, they often attempted to ambush the Americans, get a quick kill or two, then escape. The MiG-21’s impressive speed and acceleration made it well-suited to these hit-and-run tactics.

A MiG-21

The increasing number of MiG encounters in 1966 persuaded American planners of the need to deal with this threat strongly. The Johnson administration continued to disallow most attacks on airfields and bases housing MiGs through the end of 1966, when he declared another Christmas bombing halt.

1967 therefore witnessed the launch of Operation Bolo. This scheme aimed to lure the MiGs out of the safety zone of the bases on the Americans’ terms, rather than when the Vietnamese themselves chose to emerge. Colonel Robin Olds and the 8th Tactical Fighter Wing, also known as “The Wolf Pack,” would spearhead this plan.

On January 2nd, 1967, the colonel led his aircraft, 28 F-4C Phantoms armed with air-to-air missiles, in the direction of Hanoi. The F-4Cs disguised themselves as F-105 Thunderchiefs to the best of their ability, however. The jet fighters flew along a Route Pack 6A flight line usually taken by Thuds attacking permitted targets near Hanoi. They adopted the same formation as a Thunderchief raid and flew at the low speeds characteristic of Thuds still armed with exterior munitions and thus unable to go supersonic. They imitated the call signs of a Thunderchief raid, and even their radio chatter consisted of discussion of an alleged bombing target.

Adrenaline exploded through the Americans as they passed Phuc Yen airbase and the MiGs took the bait. Silver, wedge-shaped aircraft appeared, dodging through the misty cloud decks above, below, and around the Americans. For a few minutes, the Americans and North Vietnamese played a sort of lethal hide-and-seek among the cloud layers. Then combat erupted and the Americans let loose their AIM-7 Sidewinder missiles.

Colonel Olds himself managed to maneuver behind one of the MiG-21s and fired two missiles at his North Vietnamese adversary. He recalled, “The MiG-21 obligingly pulled up well above the horizon and exactly down sun. I put the pipper on his tailpipe, received a perfect growl, squeezed the trigger once […] The first Sidewinder leapt in front and within a split second, turned left in a definite and beautiful collision course correction. […] The first missile turned slightly down, then arced gracefully up, heading for impact. Suddenly the MiG-21 erupted in a brilliant flash of orange flame. A complete wing separated and flew back in the airstream, together with a mass of smaller debris.” (Lavalle, 2001, 134). The MiG, devastated by Olds’ Sidewinder, tumbled end over end before vanishing into the clouds below. The pilot did not eject above the cloud layer.

Around the pair, the American F-4C hunted the North Vietnamese pilots through the multilayered sheets of cloud, loosing their deadly AIM-7 Sidewinder radar-guided missiles at every opportunity. The North lost seven of their valuable MiG-21s, while failing to down or even seriously damage a single American aircraft.

While Operation Bolo briefly prompted the MiG pilots to adopt a cautious approach, they soon returned to their hunter-killer efforts against American aircraft raiding the North. Additionally, new Soviet and Chinese supplies of materiel swelled the available weaponry to approximately 7,000 AAA pieces and 170 S-75 Dvina SAM launchers in 1967. More MiG-21s arrived, increasing VPAF aggression in the air.

Despite the reinforcements, Operation Rolling Thunder had in fact begun to impact the North’s logistical capabilities to some extent. The sorties destroyed so many bridges and railways in 1966 that by early 1967, the brown waters of Vietnam’s inland waterways had joined the main arteries of military supply. Even after the repairs of the Christmas bombing halt, 50% of the supplies, fuel, and munitions used by the North Vietnamese military now traveled by junk, sampan, and motorized craft along rivers and streams.

Accordingly, in March 1967, Rolling Thunder sorties commenced dropping mines into the channels used by North Vietnamese military water traffic. At about this time, the weather cleared, making large missions possible again after poor monsoon visibility earlier in the year. The Americans decided to strike the steel and iron foundry at Thai Nguyen, north of Hanoi, with a series of powerful “Alpha Strikes” utilizing numerous aircraft.

The first mission on March 10th annihilated the SAM site protecting the complex, while 750-pound bombs laid waste to part of the massive facility itself. This, of course, reduced the North’s ability to fabricate new iron and steel girders to repair the bridges destroyed elsewhere by Rolling Thunder raids.

However, the North Vietnamese scored some successes, too. 85mm anti-aircraft artillery blew a Wild Weasel and two F-105 Thuds out of the sky, leading to the capture of their crews. A SAM brought down a third Thunderchief before the F-4Cs silenced the launcher. Two F-4 Phantoms, riddled with flak, crashed in Laos, though their crews ejected safely and helicopters rescued them.

The Americans hit Thai Nguyen again on March 11th, inflicting even more damage. In April and May, they bombed targets in Haiphong, including petroleum storage and barracks, along with launching attacks on airfields near Hanoi. In a notable success, the 333rd Tactical Fighter Squadron destroyed 12 MiGs on the ground on April 24th during a mission against Hoa Loc airfield.

Rolling Thunder began to resemble out and out combat more as the months passed. The North Vietnamese shot down 25 American aircraft in May 1967, capturing many of their crews. Despite the use of Wild Weasels and other electronic countermeasures, some of these losses accrued from North Vietnamese use of SAMs.

The pilots faced a conundrum when attacking high-value positions. Flying high exposed them to SAMs, while flying lower exposed them to the large batteries of AAA almost always also present. Captain Edward “Fast Eddy” O’Neil described his solution: “How can you effectively acquire a target in a highly defended, high-threat SAM area? Flying at 4,600 to 8,000 feet, jinking, jinking heavily, until you’re almost sick, works if you don’t have to stay “up” too long. If you have to be up longer than two minutes, this method is not satisfactory and the only way I think you can do it is “in the weeds.” By “in the weeds” I don’t mean so low that flying becomes more dangerous than the enemy; I mean below the peaks in the mountains and about 50 feet in the flatlands.” (Chinnery, 1988, 79).

On May 13th, Thunderchiefs of the 354th Tactical Fighter Squadron launched a major attack on the Yen Viet railyard. As the Thuds delivered their payloads to the buildings, facilities, and railway cars trapped in yard by an earlier raid, a swarm of MiG-17s and MiG-21s appeared, vectoring in from two different directions simultaneously.

The North Vietnamese pilots had reckoned without the 354th’s air cover, however. F-4 Phantoms immediately pounced, unleashing their radar-guided AIM-7 Sidewinders and opening fire with 20mm cannons. Five MiGs went down in flames and the rest fled. Elsewhere, F-4s destroyed two more MiG-17, with three more succumbing the following day for a remarkable total of 10. The MiGs did not succeed in shooting down or even seriously damaging any of their opponents.

The VPAF clashed with USN fighters from USS Bon Homme Richard and other carriers on May 21st, losing four more MiGs. Once again, the MiGs failed to destroy any American aircraft, though the AAA emplacements beneath this aerial battle more than evened the score by bringing down six American fighters.