It is just simple attention that allows us to truly listen to the sound of the bird, to see deeply the glory of an autumn leaf, to touch the heart of another and be touched.

—CHRISTINA FELDMAN AND JACK KORNFIELD, meditation teachers

It’s not easy living in a human body, but fortunately we have what it takes. We’re endowed with the human faculties of awareness and compassion. The first step toward being at ease within the body is to pay attention to it. We need to know what ails us. Then we can respond with compassion.

When we’re suffering, it’s not always immediately apparent what the problem is. If I get fired from my job, for example, I might think that I was treated unfairly and that my boss held a personal grudge against me. Sleepless in the middle of the night, I’ll despair that I’m a poor provider for my family and imagine taking revenge on my boss. Where am I, the sensitive, wounded soul, in all this? Gone! I’ve run off into my mind—taken the elevator to the top floor—and blocked out my feelings of fear and sadness. I’m arguing with the world about my personal value and scheming about the future. It’s often like that when we suffer. We can’t find ourselves in the crowd of thoughts and feelings that swirls around in our heads.

Mindfulness is a special type of awareness that can keep us anchored safely in our bodies when the going gets tough. It can grow into a way of life that protects us from unnecessary suffering. When we’re mindful, there’s less need to escape unpleasant experience—there’s a little breathing room around it. This chapter will explain what mindfulness is and what it isn’t in a way that will clarify how resisting the urge to escape pain sets us free. I’ll offer a few easy mindfulness techniques.

Mindfulness has to be experienced to be known. It can’t be expressed adequately in words. A moment of mindfulness is a kind of awareness that comes before words, such as the twinkling of stars before we call them the Big Dipper or a dash of red at the door before we recognize it as a friend wearing a new red dress. Our brains go through this preverbal level of awareness all the time, but we’re normally too caught up in the drama of everyday life to notice.

Poetry captures the simple experience of mindfulness:

Every day

I see or I hear

something

that more or less

kills me

with delight,

that leaves me

like a needle

in the haystack

of light.

It was what I was born for—

to look, to listen,

to lose myself

inside this soft world—

to instruct myself

over and over

in joy,

and acclamation.

Nor am I talking

about the exceptional,

the fearful, the dreadful,

the very extravagant—

but of the ordinary,

the common, the very drab,

the daily presentations.

Oh, good scholar,

I say to myself,

how can you help

but grow wise

with such teachings

as these—

the untrimmable light

of the world,

the ocean’s shine,

the prayers that are made

out of grass?

Mary Oliver reminds us in this poem, “Mindful,” how simple perceptions like the dance of light on a blade of wet grass can fill us with delight.

The definition of mindfulness that I find particularly useful is from meditation teacher Guy Armstrong: “Knowing what you are experiencing while you’re experiencing it.” Mindfulness is moment-to-moment awareness. There’s freedom in mindfulness because paying attention to our stream of perceptions, rather than our interpretations of them, makes every moment fresh and alive. Life becomes a festival to the senses when we’re mindful. Consider this moment of ordinary life in a poem by Linda Bamber:

Suddenly the city

I live in seems interesting

as if feeling indulgent

towards the human race, its way of

living in cities and

tearing up roads so the traffic has to be

re-routed around a collapsing white mesh barrier

as in this intersection here.

The people of this city

walking back and forth on the sidewalks

each one having gotten up and dressed this morning

look like this, this

movie, almost, of people crossing the street.

The questions,

is this scene in any way rewarding to look at?

e.g., architecturally, in terms of city spaces and human interest; and

are things diverse enough here? and

are these people, in general,

older or younger than I am? just now are

in abeyance. In their absence is this

pleasant sense that there are many cities in the world

and this is one of them.

It rained earlier. I think I’ll go see the monks

make a sand mandala on the Esplanade; and

who knows, later I might get a sandwich.

Mindfulness has a quality of being in the now, a sense of freedom, of perspective, of being connected, not judging, of flowing through the day. When we’re mindful, we’re less likely to want life to be other than it is, at least for the moment.

Some people seem to be more mindful than others, but no matter where our starting point is, we can increase mindfulness through practice. And you don’t need to be a monk or a poet to benefit from mindfulness training. You don’t even need to be calm to be mindful; you just need to make a personal commitment to be aware. You can wake up to your day-to-day life at any time or place by recognizing what’s going on in and around yourself. Ask yourself: Am I feeling confused, bored, elated, stressed, or peaceful? Can I sense tension in my stomach, warmth on my cheeks? Am I worrying about the future, what will happen when I visit my father later? Is that the sound of fluttering leaves on a poplar tree? Any awareness in present time can be a moment of mindfulness and a relief from our usual tension-producing mental machinations.

The opposite of mindfulness is mindlessness, which happens, for example, when you:

Forget someone’s name right after you are introduced

Don’t remember what you just walked into the kitchen for

Eat when you’re not hungry

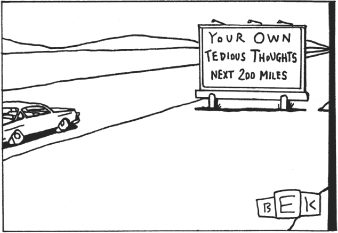

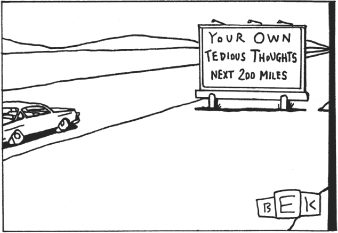

Fret about being late when you’re stuck in a traffic jam

Act like a child when you visit your parents

Drive for an hour on the highway with hardly any memory of it

These are times when we’re preoccupied, unaware of what we’re thinking, feeling, or doing, and reacting as if we’re on autopilot. You may have noticed how mindlessly we spend most of our lives!

Mindlessness is not a problem if the movie we’re playing in our heads is sweet and enjoyable, but sometimes it’s scary and we’d like nothing better than to get up and leave the theater. Our attention gets kidnapped by our suffering. This was the situation for one of my patients, George.

By all outward appearances, George was doing well in life. He had a job he liked, he had recently bought a home, he had a partner who loved him, and he could delight his friends with his skill on the guitar. But the more he flourished, the more George found that memories from his difficult childhood plagued him. He had grown up in a poor and abusive household, and his beloved sister had committed suicide when she was 16 years old. George couldn’t keep himself from sobbing whenever something good happened to him, such as getting a raise at work, buying a new car, or going on vacation. He thought about his sad childhood with his sister and how she had never had a chance to enjoy her life. His regret would not allow him to be happy. Sometimes George had flashback memories when he read news reports of battered children. His wife became concerned that she was losing her connection to George, who seemed to become increasingly preoccupied with his past as good things came their way.

George really wanted to remain close to his wife, who couldn’t help losing her patience with him at times. One day, while walking on the beach, preoccupied as usual, George noticed a beautiful round stone. He picked it up, rolled it around in his hand, rubbed it on his face, and enjoyed its cool, smooth texture on his cheeks. Since George was a collector, he absent-mindedly slipped the stone into his coat pocket. When George got home, he rediscovered the rock when he emptied his pockets. Again, it felt good to the touch: smooth, cool, and round. George noticed how rubbing it with his fingers soothed him. He dubbed it his “here-and-now stone” and kept it with him always. Whenever George found that he had a flashback memory of his childhood and didn’t want to get lost in it, he took the stone out of his pocket and ran his fingers over it.

Without any outside instruction, George had stumbled upon a way of managing his mind through mindfulness—bringing his mind into sensory awareness of the here-and-now. At first, George used his here-and-now stone to shift his attention away from what was bothering him and into the present moment. Later on, when the present moment and his stone became a reliable place of refuge when he was emotionally overwhelmed, George felt the courage to turn toward his traumatic memories, exploring them in detail. Mindfulness is both knowing where our mind is from moment to moment and directing our attention in skillful ways.

An attitude of openheartedness is necessary for mindfulness to be healing. Like a mother gazing at an infant child, we can look at something for a long period of time if it’s something we love or if we feel loved and supported while looking. It’s not possible to be aware of anything for very long if we’re disgusted by it. We can experience the exquisite beauty of a rose, or a piece of music, or ourselves only if we’re emotionally open. That’s the spirit in which we practice mindfulness.

If you did the “Waiting on Yourself” exercise at the end of the last chapter, you’ve already had a taste of mindfulness. Your mind was in a relatively receptive state, aware of a series of perceptions without needing to compare, judge, label, or evaluate them. It’s easy to live in our own minds if we simply notice what comes and goes. Problems occur when we unconsciously recoil at discomfort, grasp for pleasure, and slip into mental fantasies about how things should be. Every one of us, without exception, soon discovers that a simple exercise like sitting still for a few minutes and allowing our thoughts to come and go is anything but easy.

TRY THIS: Mindfulness of Sound

This exercise takes only 5 minutes. Find a reasonably quiet place, one in which you won’t be distracted by the TV, music, or people talking.

Sit in a relaxed, comfortable position with a straight spine. Let your eyes close, fully or partially.

Imagine that your ears are like satellite dishes picking up any sounds in the environment. Just sit and receive sound vibrations. You don’t need to label the sounds, you don’t need to like the sounds, and you don’t need to keep your attention with any particular sound— just hear whatever presents itself to you. Let the sounds come and go, one after another. Don’t try to search out sounds around you. Let them come to you.

When you notice that your mind has wandered away on a train of thought, as it inevitably will, simply return to the task of listening.

After 5 minutes, slowly open your eyes.

You might have noticed how relaxing it can be to simply pay attention to sounds, perhaps even more comforting than other methods you may be familiar with, such as relaxation training or self-hypnosis. That’s because you let go of whatever was on your mind, including the task of “relaxing,” which may paradoxically keep you on edge. You were just “being” with the symphony of sound around you.

Maybe you also discovered that you added a few extra tasks to the simple act of listening. For example, you might have labeled the sounds: “car,” “child laughing,” “door shutting.” That’s more work. You might also have wished you were in a more beautiful place, like the countryside, with sweeter sounds. That creates a little stress. And your mind probably started wandering in a very short time; perhaps you wondered if you were doing the exercise correctly, or you thought about buying a quieter air conditioner. Each of these automatic mental functions—labeling, judging, wandering mind— makes listening a little harder than it needs to be.

If you can, try the same exercise again. You could make a mental note of judging, labeling, and thinking when these mental functions kick in and then return to the sounds. Say to yourself “labeling,” when you notice you’re labeling, or “judging” when you’re judging, and “thinking” when you catch yourself lost in thought.

The mind needs an anchor. Most of our mental suffering arises when our minds jump around from one subject to another, which is exhausting, or when we’re preoccupied with unhappy thoughts and feelings. When we notice that the mind is behaving in this way, we need to give it an anchor—a place to go that’s neutral and unwavering. That’s what George did when he rubbed his here-and-now stone and what you did when you returned your attention, again and again, to the sounds in your environment. Anchoring calms the mind.

The most common anchor for the mind is the breath. There are good reasons for this:

The breath is happening 24 hours a day.

It’s easy to notice because it creates a slight movement in the body.

It’s familiar, so it can be a safe refuge from the storms of daily life.

It operates automatically, without any personal effort.

It’s our most loyal friend, accompanying us from birth to death.

Awareness of the breath is an excellent way to gather your attention and bring yourself into the present moment.

Some people find it difficult to focus on the breath. People who’ve endured physical trauma may not like being reminded of their bodies because it brings up bad memories. Those with health anxiety find that focusing on any part of the body triggers new worries. Detail-oriented or compulsive types of people may discover that when they focus on the breath their attention grips it too tightly and they experience shortness of breath. People who don’t like the way their bodies look or feel may find that attention to the breath brings them too close to their bodies in general.

If you have any of these experiences, give yourself a different anchor. The only prerequisite is that it be readily available. Some people like to use a word as an anchor—perhaps one that has special meaning (see “Centering Meditation” in Appendix B). Other choices could be the feeling of the floor under your feet, your hands folded in your lap, or an area of your body such as the heart region or a point between your eyes. If it’s difficult to bring your attention inside your body, choose an object on the surface of your body or outside it. Whatever you choose as an anchor, over time it will become like a very close friend.

The following exercise shows how to use the breath as an anchor, but feel free to substitute a different object for your attention.

TRY THIS: Mindfulness of Breathing

This exercise takes 15 minutes. Please find a quiet, comfortable place to sit. Sit in a way that your bones are supporting the muscles and you don’t need any effort to remain in one position for the whole exercise. To do this, try keeping your back straight and gently supported, with your shoulder blades slightly dropped and your chin gently tucked toward your chest.

Take three, slow, easy deep breaths to relax and let go of whatever burdens you’re carrying around. Then let your eyelids gently close, or partially close, whichever makes you feel more comfortable.

Form an image of yourself sitting down. Note your posture on the chair as if you were seeing yourself from the outside. Let your body and mind be just as they are.

Now bring your attention to your breathing. Pay attention to where you notice your breathing most strongly. Some people feel it at the nostrils, perhaps as a cool breeze on the upper lip. Other people can feel the chest rising and falling. Still others feel the breath most clearly in the abdomen, as the belly expands with every in-breath and contracts with every out-breath. Gently explore your body and discover where your breathing is easiest to notice.

Now discover whenyou feel your breath more strongly—when you exhale or when you inhale. If they’re about equal, choose one. (To simplify the instructions, I’ll assume for the rest of this exercise and throughout the book that you chose exhaling and that the location you selected was the nostrils.)

Pay attention to the feeling of each exhalation. Feel the air coming out of your nostrils each time you exhale. Then take a little vacation as your body inhales. Let your entire experience just be as you wait. Then feel your breath as your body exhales again.

Let your body breathe you—it does that automatically anyway. Simply pay attention to the sensation of the air in your nose each time you exhale, one breath after another.

Your mind will wander away from the sensation of the breath many times every minute. Don’t worry about how often your mind wanders. Gently return to the feeling of your out-breath at the nostrils when you notice that your mind has wandered.

You might be using a watch to keep track of time. Sneak a peek at your watch, and when you have a few minutes left, loosen your focus on the nostrils and allow yourself to feel your whole upper body move with each breath. Don’t bother thinking too much about it. Just feel your body, alive and moving, as you breathe.

After 15 minutes, gently open your eyes, looking downward. Savor the stillness of the moment before moving on.

You’ve probably noticed how busy the mind is. It’s very difficult to find the breath amid the clamor of competing thoughts and feelings. No sooner do we focus fully on one out-breath than the mind is off and running on a new train of thought. Perhaps you thought, “Oh, that’s a nice breath,” and as you inhaled you were already thinking of another sensation in the body or what you were going to do later in the day. When the object of our attention is repetitive and neutral, rather than novel and compelling, our brains quickly start sorting through other business.

Mindfulness of the breath cultivates focus on a single object, but you shouldn’t expect your attention to remain unwaveringly with the breath. That’s not how the brain operates. Just return your attention again and again to the breath when you notice your mind has wandered. Nothing more. It’s like the Zen saying “If you fall down six times, get up seven.” When people say, “I can’t meditate,” they’re usually referring to the erroneous assumption that they should be concentrating better. Distractions are a part of meditation. Each moment of recognizing distraction actually should be welcomed rather than used as an occasion for self-criticism, because it shows that you’ve just “woken up” from daydreaming.

In 2001, Debra Gusnard and Marcus Raichle identified a whole discrete network of brain regions—the default network—that is active when the mind is at rest and that becomes inactive when the mind is engaged in a task. When the mind wanders in meditation, it’s in default mode. The default network operates in the background, linking our past to the future and providing us with a sense of “self.” We’re usually aware of the default network only when it has failed, such as in patients with Alzheimer’s disease who appear “mentally empty.”

Giuseppe Pagnoni and colleagues at Emory University observed the default network during meditation using fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging). They asked two groups—Zen practitioners with more than 3 years of daily practice and a comparison group that never meditated—to focus on their breath, to occasionally decide whether a string of letters presented to them was a real English word (“conceptual processing”), and then to return to their breathing. Conceptual processing activated the default network. Zen practitioners were able to return to the breath and turn off the default network more quickly than the comparison group; they could rapidly abandon the stream of associations that spontaneously arose after thinking about the meaning of words. The authors speculate that this ability may help alleviate psychological conditions characterized by rumination, such as obsessive-compulsive disorder, anxiety disorders, and major depression.

It’s not clear why we have a default network. Gusnard and Raichle speculate that it’s crucial for human functioning. For example, the dorsal medial prefrontal cortex, a brain region that is active when we monitor our own thoughts, speech, and actions or those of others, is in the default network. It appears that this part of the default network is not just involved in “free association” and “mind wandering,” but also when we’re preparing for the future. Meditators should not blame themselves when their minds wander—when their brains do what they evolved to do while at rest.

Daydreaming can sometimes be a good thing, perhaps a source of creative inspiration, much like Sigmund Freud was referring to when he described our night dreams as the “royal road to the unconscious.” The key is to know when we’re daydreaming and to wake up occasionally. Unfortunately, most of the time our attention is lost in our daydreams and we suffer from stressful preoccupations—“Do I look fat?” “That was dumb!” When we return to the breath, we have a moment of respite. There are no issues when we’re in the present moment. When you’re upset, see what happens when you take a walk and focus only on the sensations of your feet on the sidewalk. No past, no future … no problem.

If you find that your stress level increases when you do the mindfulness of breathing exercise, try to do it in a new way. First of all, let go of the need to get it right. (You’ll never get it right—and you’ll never get it wrong.) Learn to work harmoniously with the mind as it is. The mind will always dredge up another memory or feeling that will disturb your concentration, so don’t despair when that happens. We don’t meditate to improve ourselves; we meditate to end our compulsive striving to do everything better. The sign of a seasoned practitioner is the willingness to return to the breath, again and again, without judgment, for decades.

Anchoring your attention in the breath does more than cultivate a focused, calm mind—it allows you to see how the mind works. It’s like holding a camera steady to take a picture. From the three exercises presented in this book so far, you’ve already learned how easily the mind wanders, compares, judges, and labels whatever it perceives. The longer you spend in meditation, the more you’ll discover about your mind. You’ll also discover a lot about yourself: your emotions, your memories, and how you react to different circumstances.

Knowing that you can always take refuge in your anchor will give you courage to explore your mind. It’s like the child who hides behind his mother’s skirt when he’s feeling timid; knowing that we can calm ourselves by returning to the anchor/breath enables us to peek back into our turbulent inner worlds.

The body is the foundation of mindfulness training. We live in a body, so to appreciate the fullness of life we need to experience the body fully. We shouldn’t think that the body is less important than the mind when we practice mindfulness. Anything occurring in the present is a suitable object of mindful awareness. Since the body is relatively slow and stable, it’s an excellent vantage point for observing our mind and emotions. The problem with trying to be aware of thoughts in mindfulness meditation is that thoughts occur so quickly that we can hardly keep track of them; they’re ancient history the moment we notice them. The mind also becomes quickly absorbed in its own ramblings when it observes itself. It’s much easier to remain aware of the present moment when we focus on the body.

We’ve already begun practicing mindfulness of the body by focusing on the breath. Now let’s open the field of awareness to body sensations around the breath.

TRY THIS: Mindfulness of Body Sensations

This exercise takes about 20 minutes. Please begin by finding a comfortable, stable position, close your eyes, and take three relaxing breaths.

Form an image of yourself. Note your posture on the chair as if you were seeing yourself from the outside.

Find your breath within your body and practice mindfulness of breathing for a few minutes. Let your body breathe itself while you feel every out-breath, one after another.

After a few minutes, release your attention from your breath and open your awareness to your entire body—to the space within the skin. Your body is vibrating with activity at every moment. Let your attention be called to whatever sensation predominates. Simply notice one, two, or three sensations in succession, such as your beating heart, moist feet, tight neck, warm hands, cool forehead, clenched jaw, or the touch of your body on the chair.

Let each sensation be just as it is. If you feel discomfort, incline toward it gently and softly in your mind.

Let your attention be with body sensations as long as it’s naturally drawn there and then return to your breath. You can return to your breath anytime you need to gather and stabilize your attention.

Then open your awareness again to whatever body sensations call to you—whatever you feel most strongly. Take it slow and easy. The task is to remain with sensations occurring in the present moment, not to identify as many sensations as possible.

For the remaining 10 to 15 minutes, let yourself feel your breathing and then feel any other predominant sensations in the body. Go back and forth between the breath and other sensations in a relaxed, leisurely manner. Notice your breathing alongside the other sensations going on in your body. Be fully embodied, breathing and feeling.

Gently open your eyes.

Did you feel yourself relax when you returned to the breath after being aware of the other sensations in the body? Perhaps you had the opposite experience—that focusing only on your breathing felt constricting and full-body awareness was a relief?

Mindfulness meditation is commonly a dance between single-focus and open-field awareness. When our attention is too tight around the breath, causing stress, we can relax by opening our awareness to other perceptions. Alternatively, when our attention is swept up in the tornado of events continually occurring in the body or mind, we can find shelter from the storm in one-pointed attention to the breath.

There are two categories of mindfulness meditation: formal and informal. “Formal” mindfulness meditation is when we dedicate time—usually half an hour or longer—to being mindful of what we’re sensing, feeling, and thinking. “Informal” meditation is when we take a brief, mindful moment in the midst of our busy lives. Both approaches can be practiced while sitting down, standing, walking, eating—anywhere and anytime. The difference between formal and informal meditation is mainly a matter of time and purpose.

Each person should decide for him- or herself whether it makes sense to establish a formal meditation practice. Formal practice is more intensive, which generally transforms the mind at a deeper level: it yields deeper insights into the nature of mind and our personal conditioning. If you wish to do formal meditation, it should be enjoyable and it should fit your temperament and lifestyle. Most people don’t want to squeeze yet another activity into their busy schedules. Nor should they. This book is not written for people who want to become meditators, although some readers might develop a taste for it. The formal meditation practices here are offered primarily so you can have a direct experience of mindfulness and self-compassion, and they can be used as a model for practicing more informally.

Formal meditation is never an end in itself; life itself is the real practice. It’s hard to stay conscious and aware amid the flood of sensory impressions and emotional reactions we encounter in daily life. Consider your mind state on a morning when your baby daughter has been sick all night, you have to make a presentation at the office in 3 hours, the freezer door was left open all night and ice cream is dripping on the floor, and your babysitter is on vacation. Many parents would find themselves crying on the kitchen floor. Maintaining presence of mind to handle problems calmly and efficiently is a skill that grows with meditation practice. If you spend a chunk of time every day exploring your inner experience in formal meditation, the same kind of compassionate self-monitoring is more likely to continue throughout the day, even during the worst of times.

Formal mindfulness meditation especially helps us figure out how to live with discomfort—to inhabit our bodies in a way that doesn’t turn everyday physical and emotional pain into a larger problem. Depending on how you’re feeling from moment to moment, you might focus your attention on the breath, explore a body ache, return to the breath, sense an emotion, find the emotion in the body, breathe, soften the body a little, breathe, listen to sounds in the environment, return to the breath, and so on. This practice gives us, in Jon Kabat-Zinn’s words, the freedom to “respond” rather than “react.” We can make wise choices about our lives: “Shall I eat that snack? Should I argue with my spouse right now? Is this a good time to act on a sexual urge?”

How much formal meditation is generally recommended? The usual length of time is 30 to 45 minutes daily. That amount has been shown to increase well-being and even enhance the immune system. Busy people are more likely to meditate for 20 minutes, once or twice a day, which is also good. Improvement appears to be “dose-dependent”—it depends on how much training is given.

In 2003, Richard Davidson, Jon Kabat-Zinn, and colleagues found that 8 weeks of mindfulness meditation training (mindfulness-based stress reduction [MBSR]), 1 hour daily, 6 days a week, produced lasting changes in the brain and the immune system. Twenty-five stressed-out biotech employees were trained to meditate, and they were compared to 16 people who received no training at all. After the meditation training, everyone was asked to write down one of the most positive experiences of their lives and one of the most negative experiences. EEG recordings were made of their brains before and after the writing exercise. Their blood was also drawn to measure how many antibodies they produced in response to a flu vaccine.

EEG recordings showed that meditators had increased activation in the left side of the frontal region of their brains, an area associated with positive emotions. This brain activity was evident even when meditators wrote about negative experiences in their lives, suggesting that they had learned to adapt well to unpleasant mind states. Blood tests were given at 4 and 8 weeks after the flu vaccine was administered and meditators generated more antibodies than nonmeditators, demonstrating stronger immune systems. Interestingly, the number of flu antibodies correlated with left-sided brain activation among the meditators—more left frontal activation, more antibodies.

In 2008, David Creswell and colleagues also measured the impact of the MBSR program on immune functioning. They trained an ethnically diverse sample of 48 HIV-positive patients in the MBSR program and thereafter counted the number of CD4 T cells—the cells that are destroyed by the HIV virus. (CD4 T cells are considered the “brains” of the immune system that protect the body against attack.) Creswell and colleagues found that “the more mindfulness meditation classes people attended, the higher the CD4 T cells at the study’s conclusion.”

Charles Raison and colleagues at Emory University examined the effect of meditation on the inflammatory protein, interleukin-6. Chronic stress increases plasma concentrations of IL-6, and elevated IL-6 predicts illnesses such as vascular disease, diabetes, dementia, and depression. The researchers compared a group of students who completed 8 weeks of compassion meditation (with some mindfulness meditation) to a group that had twice-weekly health discussions. Afterwards, all students were put under stress in a public speaking and mental arithmetic challenge. No clear differences in IL-6 were found between the meditation and control groups. However, meditators who practiced more than average had significantly lower levels of IL-6 compared to their less zealous colleagues, suggesting that mind training can reduce inflammatory responses to stress.

Some parts of the brain even grow thicker when we meditate daily over a period of years. Sara Lazar and colleagues at Harvard University measured whether long-term mindfulness meditation can change the physical structure of the brain. They found that the prefrontal cortex and the right anterior insula—regions associated with attention, internal awareness, and sensory processing—were thicker in long-term meditators than in matched controls. Furthermore, cortical thickening correlated with years of meditation experience and seemed to offset thinning of the cerebral cortex that naturally occurs as we age.

The psychological mechanisms by which long-term mindfulness meditation translates into less suffering are under preliminary investigation. One hypothesis is that our difficult memories lose their edge if they arise when we’re in a calm state of mind— “interoceptive exposure.” Another is that we learn to regulate our attention, and knowing when and where to place our attention helps us regulate emotion. George did this by focusing on his here-and-now stone when he was overwhelmed by trauma flashbacks. Yet another potential mechanism of action for mindfulness meditation is “metacognition,” the ability to step back and witness our thoughts and feelings rather than getting hijacked by them.

Perhaps the most compelling explanation for why mindfulness works is that, over time, we acquire beneficial insights about life. We discover how everything changes, how we create our own suffering when we fight change, and how we unconsciously cobble together a sense of “self.” The latter insight is beneficial because most of our waking moments are spent vainly boosting or fearfully protecting our fragile egos from assault. (More is said about this baffling, yet important, topic near the end of Chapters 4 and 5.) When these insights about life become deep and abiding, they help us receive success and failure with equanimity, tolerate emotional pain knowing “this too will pass,” and have the courage to seize each precious moment of our lives. In other words, intuitive insights derived from intensive meditation can help us establish a less defensive, more flexible, relationship to the world.

Mindfulness is not trying to relax. When we become aware of what’s happening in our lives, it can be anything but relaxing, especially if we’re stuck in a difficult situation. As we learn more about ourselves, however, we become less surprised by the feelings that arise within us. We develop a less reactive relationship to inner experience. We can recognize and let go of emotional storms more easily.

Mindfulness is not a religion. Although mindfulness has been practiced by Buddhist nuns and monks for over 2,500 years, any purposeful activity that increases awareness of moment-to-moment experience is a mindfulness exercise. We can practice mindfulness as part of a religion or not. Modern scientific psychology considers mindfulness to be a core healing factor in psychotherapy.

Mindfulness is not about transcending ordinary life. Mindfulness is making intimate contact with each moment of our lives, no matter how trivial or mundane. Simple things can become very special—extraordinarily ordinary—with this type of awareness. For example, the flavor of your food or the color of a rose will be enhanced if you pay close attention to it. Mindfulness is also about experiencing oneself more fully, not trying to bypass the mundane, ragged edges of our lives.

Mindfulness is not emptying the mind of thoughts. The brain will always produce thoughts—that’s what it does. Mindfulness allows us to develop a more harmonious relationship with our thoughts and feelings through a deep understanding of how the mind works. It may feel as if we have fewer thoughts, because we’re not struggling with them so much.

Mindfulness is not difficult. You shouldn’t feel disheartened when you discover that your mind wanders incessantly. That’s the nature of the mind. It’s also the nature of the mind to eventually become aware of its wandering. Ironically, it’s in the very moment when you despair that you’re not mindful that you’ve become mindful. It’s not possible to do this practice perfectly, nor is it possible to fail. That is why it’s called a “practice.”

Mindfulness is not escape from pain. This is the toughest idea to accept because we rarely do anything without the wish to feel better. You will feel better with mindfulness and acceptance, but only by learning not to escape from pain. Pain is like an angry bull: When it’s confined to a tight stall, it will be wild and try to escape. When it’s in a wide-open field, it will calm down. Mindfulness makes emotional space for pain.

Mindfulness in daily life is “informal” meditation practice. Short moments of mindful awareness can substantially reduce the stress that we accumulate throughout the day. And it feels good to just be, if only for a few seconds.

Informal practice means we choose to pay attention, on purpose, to what’s occurring in the present moment. Any moment-to-moment experience is a suitable object of mindfulness. That could mean listening to birds, tasting your food, feeling the earth beneath your feet as you walk, noticing the grip of your hands on the steering wheel, scanning your body for physical sensations, or noticing your breathing. It could be as simple as wiggling your toes. The present moment liberates us from our preoccupations, never judges us, and is endlessly entertaining.

Don’t underestimate the power of brief mindfulness exercises. A report in the psychological literature describes a 27-year-old man, James, who suffered from mild mental retardation and mental illness. He was hospitalized several times for aggressive behavior. During one hospitalization, James received mindfulness training twice a day for 5 days, plus assignments for another week. The training went like this:

Stand or sit with your feet flat on the floor.

Breathe normally.

Think of something that leads to feeling angry.

Shift your focus to your feet and wait until you feel calm.

James practiced this “soles of the feet” meditation whenever he became angry. One year later, his aggressive behavior had decreased significantly, he was able to stop taking all the medication he had been on, and his caregivers no longer considered him mentally ill.

The most important thing to keep in mind when you tailor mindfulness exercises for yourself is to make them as pleasurable as possible. Mindful awareness comes naturally when we’re enjoying ourselves.

All mindfulness exercises have three basic components:

Stop

Observe

Return

First we need to stop what we’re doing. If you’re arguing on the phone, you can take a moment of silence. If you’re caught in a traffic jam and worrying about being late, you might take a deep, conscious breath. Slowing down also facilitates mindfulness. If you eat more slowly, you’ll be more aware of what you’re eating, and you might even give your body a chance to tell you when you’re full. When you reduce your walking speed, you’ll see more of your surroundings.

Observing doesn’t mean detachment or being overly objective. Instead, you want to be a “participant observer,” intimately engaged with the experience. Life is bubbling within you and you’re in the middle of it, yet you can observe.

If calming down is your wish, it helps to have a single point of observation, such as the breath. If you want to explore and understand what you’re feeling at the moment, you can scan your body for sensations and perhaps label your emotions: “anger,” “fear,” “sadness.” (Much more will be said about mindfulness of emotions in the following chapter.)

When you notice that your attention has been swept away into daydreams, gently return it to the focal object. If you’re in nature and wish to be more mindful of your surroundings, that may mean returning again and again to the sounds of the forest. If you’re chopping vegetables, it’s a safe bet that you’ll want to pay attention to the distance between your finger and the blade of the knife. (The closer our fingers get to the blade, the easier mindfulness becomes!)

Whenever you feel stuck or confused, you can begin making the situation workable by taking a mindful breath: just stop what you’re doing and feel your breath. You can take a conscious breath anytime: in your car at a red light, during a business meeting, or while your child is having a tantrum. Let yourself be immersed in the nourishing experience of breathing. When you feel calmer and your mind has cleared, give yourself a chance to choose what to do next. Conscious breathing is the easiest, most common mindfulness technique; remembering to do it in the midst of our busy lives is the challenge.

Walking meditation is a delightful practice, especially if you’ve been sitting all day long and need a little exercise. You can practice walking as a formal, 20- to 30-minute meditation, or in spurts—as you walk to the bus stop or from your car to the grocery store. Anytime your feet hit the pavement, you can meditate. Of course, a meditative walk in the woods is a special way of opening to the beauty of nature.

Plan to walk for 10 minutes or longer. Find a quiet place in your home where you can walk back and forth at least 20–30 feet at a time or in a circle. Make the decision to use the time to cultivate moment-to-moment kindly awareness.

Stand still for a moment and anchor your attention in your body. Be aware of yourself in the standing posture. Feel your body.

Start to walk slowly and deliberately. Notice how it feels to lift one foot, step forward, and place it down as the other foot begins to lift off the floor. Do the same with the other foot. Feel the sensations of lifting, stepping, and placing, over and over again. Feel free to use the words “lift,” “step,” “place” to focus your attention on the task.

When your mind wanders, gently return to the physical sensations of walking. If you feel any urgency to move faster, simply note that and return to the sensations of walking.

Do this with kindness and gratitude. Your relatively small feet are supporting your entire body; your hips are supporting your whole torso. Experience the marvel of walking.

Move slowly and fluidly through space, being aware that you’re walking. Some people find it easiest to keep their attention below the knees, or exclusively on the soles of the feet.

When you reach the end of your walking space, pause a moment, take a conscious breath, remain anchored in your body, and reverse direction.

At the end of the meditation period, invite yourself to be mindful of body sensations throughout the day. Notice the sensations of walking as you go on to your next activity.

Do this exercise first at home, walking very slowly, and later walk at a normal pace when outside in public. It can be very grounding to feel the earth beneath your feet, especially when you’re in a hurry or emotionally upset. Some people prefer to just focus on their breathing while walking. That’s fine too. As in all mindfulness exercises, feel free to experiment and discover what works best for you.

In the next chapter, we turn our attention to emotions: What are they? Where do they come from? How can you use mindfulness to deal with them, and why does it work?