Thinking through Gramsci in Political Theory: Left/Right and the Critical Analysis of Common Sense

At this point it might be useful to summarize the argument so far. In Part One we gave a brief overview of Gramsci’s biography and his intellectual development, and discussed some of his most important pre-prison writing. In Part Two we offered a reading of Gramsci’s thought, particularly as developed in his Prison Notebooks. We structured our reading of Gramsci around the concepts of culture, politics, philosophy and hegemony. Specifically, we contended that the concept of hegemony forms the basis of Gramsci’s account of history and political strategy, and that it is important to understand his other key concepts in terms of their relation to hegemony. In our reading, it is necessary to place Gramsci’s thought in the context of his understanding of Marxism; crucially, the parts of his thought that may at first appear disparate and unconnected are in fact tightly joined together as different but complementary aspects of a unified project of the renewal of historical materialism.

In Part Three we attempt to illustrate what we take to be Gramsci’s distinctive method of social analysis, namely the development of new concepts and theoretical insights from historical inquiry. It is therefore necessary to focus on two relatively narrow case studies; in this sense the aim of Part Two to provide a systematic account of the basic structure of Gramsci’s thought is replaced with the aspiration of Part Three to show what ‘thinking through’ Gramsci today might look like in practice. As a consequence of this change in the aims of the argument, we have often found it necessary to move from an exposition of Gramsci’s concepts to a detailed examination of historical reality. In both this chapter and Chapter 7, therefore, we depart some distance from the reading given in Part Two, but we aim to do so following a consistently Gramscian methodology.

We hope that the two case studies of Part Three – the notion of Left/Right as part of the ‘common sense’ of modern politics and the spread of neo-liberalism in Britain and France in the 1980s – also support two further arguments. First, that Gramsci’s thought is useful and usable in the twenty-first century, even in fields as traditionally distant as Political Theory and Political Economy. Second, that Gramsci’s thought is unfinished but it is also flexible. By this we intend to mean that it is necessary but possible to supplement the conceptual framework that Gramsci developed in his Prison Notebooks with new concepts that emerge from the empirical inquiries that take his concepts as their starting points. Accordingly, in this chapter we propose the concept of political narrative as a way to develop Gramsci’s understanding of common sense, while in Chapter 7 we suggest a distinction between coherent and split historic blocs as a development of one of Gramsci’s most important but difficult concepts.

The present chapter is structured so as to develop what we take to be a possible Gramscian methodology for the investigation of senso comune, or common sense. This is one of the central concepts of Gramsci’s philosophy (see Chapter 4). The argument of this chapter develops through an extended examination of the history, meaning and function of the commonsensical assertion that ‘politics is about a battle between a Left and a Right’, which we summarize as ‘Left/Right’. As we will see, this is a widespread but deceptively complex way of ‘making sense’ of the social field of politics. We analyse Left/Right along a number of dimensions, then, which we take to represent the steps in a Gramscian methodology for the analysis of given pieces or ‘fragments’ of senso comune. First, we contextualize Left/Right by situating it in relation to everyday life and seeing how it might ‘make sense’ of social life outside of the political sphere. Second, we ‘historicize’ Left/Right by tracing its history and origins. Third, we analyse the formal and linguistic characteristics of the Left/Right metaphor. Fourth, we attempt to uncover the ‘conception of the world’ contained in Left/Right; in other words we look at the understanding of politics on which Left/Right is premised. Fifth, and most tentatively, we take Left/Right as a story about politics, and relate it to class struggle as a competing narrative of political conflict. We develop the concept of ‘political narrative’ to capture how commonsensical stories about politics gain some of their efficacy not by being true or false but by being compelling or ‘successful’ narratives (according, that is, to the criteria we might want to begin to think about for the assessment of the success of narratives). We would propose that our methodology could be used by those who would wish to investigate fragments of senso comune in other contexts (such as assertions about gender relations or our relation to the environment).

The focus on Left/Right in this chapter is justified, we would assert, because it stands as a fragment of common sense like any other. If it is possible to show how complex and important is the ideological work that it performs, then this opens the possibility that other fragments of common sense might be susceptible to similar sorts of analyses. It is also important for us to make it clear to the reader that existing studies of Gramsci’s thinking on senso comune focus on three fundamentally theoretical tasks: establishing the place of common sense in Gramsci’s wider revolutionary project; theorizing the relationship of common sense and the concept of ideology; and asserting the formal and abstract characteristics of common sense.1 What is required truly to follow up and extend Gramsci’s researches on senso comune is for us to ‘get our hands dirty’ by analysing common sense as it actually exists in all its contradictoriness and complexity, rather than theorizing it in the abstract. It is in this spirit of following Gramsci’s thought that we attempt to develop some pointers for what Gramsci might have called the ‘critical analysis of the philosophy of common sense’.2

Contextualizing common sense: Left/Right in politics and everyday life

We select ‘Left/Right’ as the fragment of common sense to analyse in this chapter because it is one of the most widely held and easily recognized common sense accounts of politics. Research in political sociology finds consistently high rates of European voters recognizing Left/Right and placing themselves on the scale.3 This result is also repeated, with variation, across the world.4 In one study, almost all of the 1,500 experts – academics, political analysts, think tank workers and so on – asked found it possible to apply Left/Right to the parties in their country.5 A notion of Left/Right is one of the most intuitively accessible and pervasive accounts of the political universe, and has been described as the equivalent of ‘political Esperanto’.6 It is a commonplace political item: ‘few notions, indeed, are as ubiquitous as the idea of a division between the left and the right in politics’.7 Thinking historically, Left/Right has been called the ‘great bipolar’ of Western European politics prior to 1989 and the ‘grand dichotomy’ of twentieth-century political thought.8 As Bobbio puts it, Left and Right are ‘two antithetical terms which for more than two centuries have been used habitually to signify the contrast between the ideologies and movements which divide the world of political thought and action’.9 Finally, at the aggregate level, we might conclude that ‘left and right have defined the broad space of political antagonism in modern Western societies’.10 In political sociology, the model of Left/Right is ‘an enduring element in comparative analysis’.11 It is not an overstatement to say that Left/Right is one of the most common ways of making sense of politics.

However, it is not the case that Left/Right is the only possible way of making sense of politics. We must remember that common sense is a heterogeneous mass of propositions about a given domain of social life, and is undergoing constant change (see Chapter 4). In particular, Left/Right might have been seriously questioned since 1989.12 Today, Left/Right might be challenged by an understanding of politics that promotes a kind of apathy or detachment on the basis that ‘there is no alternative’ to liberal capitalism.13 Alternatively, there might be an important commonsensical understanding that politics is a realm dominated by venal, unscrupulous and hypocritical politicians who look to con rather than represent the electorate. Nevertheless, Left/Right is a widely recognized understanding of politics, and plausibly forms part of contemporary common sense.

The first step in the ‘critical analysis’ of Left/Right as a fragment of common sense, as following the methodology specified above, is to ground Left/Right as a part of the contested common sense of politics in the wider context of other ways of making sense of the world using a spatial metaphor based on a split between a left and a right.

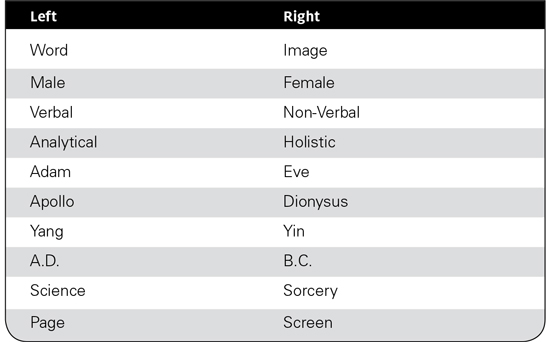

The significance of the division of reality into a left and a right extends far beyond their usage in modern politics. The design theorist David Crow, in his Left to Right: The Cultural Shift from Words to Pictures (2006), presents Left/Right as the key dichotomy through which to understand contemporary visual culture in the bold red double-page spread with which his book opens (see Table 6.1).14

Table 6.1 Associations of Left and Right in visual culture

Source: Crow, Left to Right.

Crow contends that we are witnessing a societal transition from his list of ‘Left’ characteristics to those he associates with ‘Right’, in much the same way we read English text from left to right. We may disagree with Crow’s understanding of visual culture in late capitalism, but his choice of presenting the transition through the heuristic of Left/Right suggests the assumption of a deep familiarity with the symbolic division on the part of his readers. Left/Right here provides the master division relevant to the explanation of visual culture in whose terms other divisions – such as between Apollo and Dionysus or Page and Screen – can be understood. We may also disagree with Crow’s choice of left and right categories; perhaps, though, this disagreement is only possible due to the strong collective set of associations between left or right and a set of other concepts or ideas.

Indeed, anthropologists have long been interested in the symbolic division between left and right. The recognized starting point of anthropologists’ interest in Left/Right was Robert Hertz’s 1909 essay ‘The Pre-eminence of the Right Hand’. Hertz died in the First World War, and much of the influence of the essay in Anglophone anthropology came through its promotion by E. E. Evans-Pritchard while the latter held the Chair of Social Anthropology at the University of Oxford. Hertz’s essay pointed to three elements of relevance here. First, Left/Right was seen to be virtually a cultural universal: a dualistic spatial classificatory metaphor, with symbolic differences between the left and the right, was pointed out by Hertz and found by every subsequent anthropologist who has searched for it. More recent studies have if anything extended this finding, with Left/Right seeming to be applicable to virtually all areas of social life and research. James Hall, in an interesting account, traces the history of Left/Right dualism in the history of Western art, noting that especially since the Renaissance there has been a consistent and clear connection between left and the overtly or ‘femininely’ emotional, perhaps as a consequence of the belief of the physiological connection of the left side to the heart.15

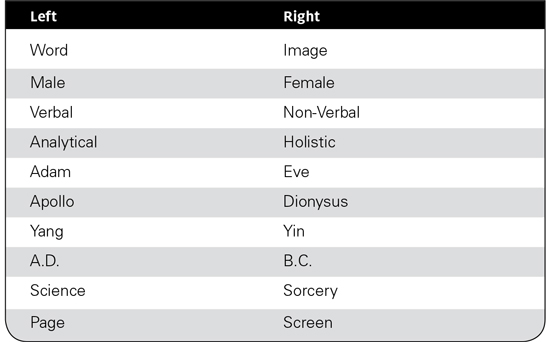

Second, in Hertz’s account – and again as found by later anthropologists – right is privileged over left. The political theorist Steven Lukes interprets the anthropological evidence as suggesting ‘the pre-eminence of the right is virtually a cultural universal’.16 In Needham’s fascinating account of ‘Right and Left in Nyoro Symbolic Classification’, included in a collection of responses to Hertz’s essay, we can see the sheer range of Left/Right associations that concern many dimensions of everyday life, as shown in Table 6.2.17

Table 6.2 Associations of Left and Right in Nyoro society

Source: Needham, ‘Nyoro Symbolic Classification’.

Other contributions to the collection of responses to Hertz’s essay also find a Left/Right symbolic classification to be important, among other cases, in Southern India, China, Africa and Greek philosophy.18 As McManus puts it, ‘Wherever one looks, on any continent, in any historical period or in any culture, right and left have their symbolic associations and always it is right that is good and left that is bad.’19

Third, Hertz also argues that the ultimate root of Left/Right symbolic classifications is religious. Three examples may be given from the Bible: in Matthew 25.33, God sets the sheep on his right hand, with the goats on his left; in Matthew 26.64, the association is made between sitting on the right hand of God and power; and, in Genesis 1.28, God makes Eve out of Adam’s left side. While the assessment of the religious origins of Left/Right is not a key focus here, this reinforces the point that Left/Right as a political classification only emerged in the modern period, so we must be aware that other classificatory systems may have existed before it and indeed competed with it as an heuristic through which to understand politics.

In assessing this evidence, McManus talks of ‘a universal human desire to treat left and right as symbolically different’.20 However, following Gramsci, we might rightly be wary of claims to universal human traits. Nevertheless, the ubiquity of Left/Right and the pre-eminence of the right do seem to be robust findings. It seems sensible to follow Ignazi in concluding that

the term Right displays both an amazing stability over time and large diffusion in the Indo-European languages; on the contrary, the term Left is highly unstable and undifferentiated … . Right is associated to positive adjectives such as honest, reliable, straight, even lively, to the juridical right and to political rights; while the term Left is linked with malicious, dangerous, unaccountable, untrustworthy, incapable, and even deathful.21

We might contextualize Left/Right as part of common sense in the following way: Left/Right as part of the common sense of contemporary politics is situated in the context of the presence of left/right frames in a wide variety of symbolic systems. In these systems, the right seems to be consistently privileged.

Historicizing common sense: Left/Right since the French Revolution

The second step in the methodology for investigating common sense that we are proposing here is to examine as closely as possible the origins and historical development of the individual fragment of common sense under investigation. Thus, in this section we trace the emergence of Left/Right as part of the common sense of politics. Again, we attempt to be illustrative rather than exhaustive in our account.

Left/Right is commonly thought to have entered political vocabulary in the context of the French Revolution. Importantly, the horizontal metaphor of Left/Right is contended to have replaced a vertical political metaphor that previously classified the estates hierarchically as the monarchy and nobility, the church, and the mass public. One historian traces the precise date of the establishment of the left–right divide to 28 August 1789, when the Estates-General – in session since May and by August a constituent assembly – began in Versailles to debate whether the king should have veto rights and consequently authority above that of the representatives of the people. Representatives in favour of the royal veto sat to the right of the speaker and those in opposition to the left.22 Caute also highlights that in the debate over popular sovereignty, views on the structure of the legislature divided across Left/Right lines, with the Right – and Centre – favouring an upper chamber, and the Left opposing any hereditary element and calling for a single-chamber legislature.23 Significantly for Ignazi, the horizontal ‘spatial uni-dimensionality founded upon the Left-Right antinomy clearly identifies, at the moment of its foundation, a basic opposition: equality against privilege’.24 Crucially, even at its moment of inception, the Left/Right metaphor represented a simplification of the actual state of political conflict. Similarly, we might argue in general that it is a simplification to say that the French Revolution was entirely reducible to a clash between equality and privilege. In the Constituent Assembly of 1789–91, we can in fact distinguish four primary groups which – although shifting positions on different issues – could be labelled the Right (Cazales, Maury), the Centre-Right (Les Monarchiens), the Centre-Left (Le Chapelier, Grégoire, Lafayette, Bailly) and the Extreme Left (Robespierre, Pétion de Villeneuve).25 Left/Right was not, even at the point of its origin, a way of thinking about politics that totally avoided simplification. It seems likely that simplifying complex reality is one of the characteristic functions of common sense understandings of any social phenomenon.

It seems possible, though, that the ‘birth and sporadic use’ of the Left/Right metaphor was a ‘false start’ because ‘although it distinguished opposed political groupings in the legislatures (initially those for and against the king’s suspensive veto), the predominant preoccupation during this period was to abolish all political divisions’.26 Instead, argues Lukes, its ‘true birth dates from the restoration of the French monarchy following the defeat of Napoleon, and in particular from the parliamentary session of 1819–20’, when the terms Left and Right entered into political practice as distinguishing liberals from ultras and deriving from the memory of 1789.27 Further, according to Marcel Gauchet, ‘The 1819–1820 session of parliament marks one of the great moments in the history of political vocabulary. The whole lexical system was apparently clarified and consecrated at this time. Newspapers, pamphlets, and private correspondence all confirm that the terms left and right now began to be used not just in isolated instances but in a consistent and regular fashion.’28 Thus, the entry of Left/Right into the common sense of French politics is likely to have occurred considerably later than the time of the French Revolution, when perhaps it identified a division within the political elite but was not yet widely used by the French people to make sense of politics.

Already, then, at the time of its entry into common sense the main use of Left/Right was to call up a previous political conflict, and to present, in a stylized fashion, the protagonists of one debate in the terms of an older one. The solidification of the Left/Right framework as a common sense understanding of politics became widespread in French politics with the increasing importance of class in the course of the nineteenth century.29 Critically, for Lukes ‘it was with the achievement of universal manhood suffrage in France in 1848 that Left and Right entered mass politics, applying not merely to the topography of the parliamentary chambers but now as categories of political identity, spreading rapidly across the parliamentary systems of the world’.30

We can thus trace the origin of Left/Right as a political metaphor to French politics in the mid-nineteenth century, in which the previous political division of the French Revolution was invoked to make sense of the conflict then occurring. The diffusion of Left/Right varied cross-nationally over the course of the nineteenth century, except in Britain where Left/Right terminology continued to be outweighed by the Whig–Tory dichotomy.31 Indeed, Brittan notes that the terms ‘Left’ and ‘Right’ were first used in the British context as late as 1837, and even then did not gain general currency until the 1920s.32 In short, the most we can conclude in the absence of detailed national studies is that Left/Right only became decisively established in Western Europe with the spread and increasing salience of the class cleavage, and even then not unproblematically. It would be interesting to trace the development of the language of Left/Right in the British context, and particularly its relation to the previously dominant Whig–Tory dichotomy.

Even the brief account given here suggests that the common sense view that ‘politics is about Left versus Right’ has an important history, initially emerging in France in the nineteenth century to recall the earlier division of the French Revolution. Importantly, common sense, like all ways of thinking about society, is an inherently historical phenomenon – even if it might not immediately reveal its historicity. Starting to make an inventory of this history is an important step in the critical analysis of common sense.

Analysing common sense: The formal characteristics of the Left/Right metaphor

Common sense, we would assert, must be taken seriously and investigated using the methods of close philosophical analysis in addition to attempts to historicize and contextualize it. Specifically, we can as a third step in the critical analysis of common sense investigate the language and the formal structure of the fragment of common sense under analysis, aiming to see how it constrains the understanding of the specific topic to which it refers.

The metaphor of Left/Right, at its most basic level, divides the horizontal dimension of space into at least the two categories of the ‘left’ side and the ‘right’ side. It has a number of consequent theoretical attributes. First, it is symbolic or ‘abstract’. Second, it is spatial. Third, the space it refers to is horizontal. Fourth, particularly in the language of Left versus Right – one possible unpacking of Left/Right – a conflictual or at the least oppositional relationship is suggested. Fifth, Left and Right are assumed to be mutually exclusive categories. Sixth, Left/Right is flexible – or ambiguous – between positing a spectrum or a binary division. Finally, we might also ask whether the metaphor of Left/Right purports to apply to all aspects of political life since as a consequence of its symbolic nature there are no formal barriers to describing any political phenomenon in terms of Left/Right. It may in this sense be an ‘exhaustive’ description of political life. We address these points in turn below.

First, the metaphor of Left/Right is abstract, as it does not refer to specific beliefs or entities in the way that the dualism between, say, ‘monarchism’ and ‘republicanism’ does. The symbolic nature of Left/Right has three important consequences. First, we can see how there may be a way in which Left and Right can be thought to be mirror-image opposites. Republicanism is rarely put forward as the opposite or negation of monarchism; it does not simply mean ‘no king or queen’ but also the belief in the power of the people to govern themselves through a system of popular rule. Second, the terms Left and Right are sufficiently general to be applied to a wide variety of referents, as we observe in political life. Left and Right are ubiquitous, then, partly due to the lack of formal limitations or difficulties in their application to any argument, actor or issue. Third, and most complexly, the symbolic nature of Left and Right means that, for their use in politics, these terms have ‘to acquire, to be filled with, concrete meanings’.33 In other words, the framework of Left/Right is held by some theorists to be formally ‘contentless’, needing ‘outside’ political debates to give the division meaning. This contention is considerably complicated by the fact that Left/Right emerged in a specific historical context, and the terms Left and Right were from the very start associated with a set of positions held by French Left and Right in the late eighteenth century. The language of Left/Right emerged to describe a specific political conflict, and when it re-emerged during the Restoration it was on the basis of this intimate link with that conflict. The most that we can say, therefore, on the symbolic or abstract nature of the language of Left/Right is that it is a formally abstract metaphor, which the history of the past 200 years shows us has been associated with a historically shifting set of political situations that have given the words content. To put it precisely, the symbolic or abstract nature of the metaphor of Left/Right plausibly is ‘filled in’ by a relationship to the historically specific political conflict in the political system it is being used to describe.

Second, in addition to being abstract, the metaphor of Left/Right is also spatial, in that it relates to a dimension of physical or hypothetical space. This distinguishes Left/Right from Red/White or Black/White as a common sense description of politics. Interestingly, Black/White might be thought to be a closer relative to Left/Right than Red/White in one sense: black and white are commonsensically thought of as opposites in a way that white and red are not. However, Red/White has historically been an important and evocative symbolic description of politics, most famously in the war between Trotsky’s Red Army and the counter-revolutionary Whites in the aftermath of the Revolution. We can also compare Left/Right as a ‘political symbolic order’, in Dyrberg’s terms, to that of similarity/difference as a non-spatial metaphor.34 Left/Right also, more subtly, presupposes some distance between Left and Right, on whatever dimension is being talked about: the space between Left and Right is created by difference between Left and Right in some relevant aspect. Otherwise, Left and Right would occupy the same location within the metaphor, rendering a specifically spatial metaphor redundant or confusing. Here, we can imagine scanning the seated representatives in the French Assembly – or another parliament – from Right to Left: one would see a clear and profound change in political ‘positions’ as corresponding to the seating positions.

Third, the space described by Left/Right is a horizontal plane. Alternative spatial metaphors that could be applied to politics include a metaphor of vertical space (such as of heaven and hell, up and down, or the three ordered estates preceding the French Revolutionary context), one of concentricity, one of proximity or distance, one that divides up space into an included and excluded area, or the overlapping boundaries of Venn diagrams. As Dyrberg notes, other spatial metaphors prominent in contemporary politics include centre/periphery and front/back.35 Much has been made of the ‘principle of parity’ in which Left and Right appear to be placed on the same horizontal plane, and so seem to be equals in argumentation and political action.36 The language of Left/Right, then, allows those using it to make claims about the nature of political conflict – should they choose to – since it contains within it what we might clumsily call ‘democratic potential’: it formally places two antagonists on a level horizontal plane.

Fourth, the language of Left versus Right also suggests a conflict, antagonism or competition between the two camps. Left versus Right suggests that an essential feature of politics is the split of opinion and action into two camps, and the conflict between these camps. It is an open question the extent to which a Left versus Right model implicitly leaves space for a ‘ … versus Centre’ addition.

Fifth, the language of Left/Right is also premised on the idea that Left and Right are mutually exclusive categories – simply put, Left/Right is not an appropriate metaphor if both Left and Right refer to the same thing. There is, in addition, an assumption that the mutual exclusivity of Left and Right will be durable over time or, in other words, that the metaphor will make sense tomorrow in the same way as it does today – that is, through the drawing of boundaries of mutual exclusivity.

Sixth, Left/Right can posit either a spectrum or a dichotomous division. In the former case, categories such as Centre, Centre-Right and Far-Right can be introduced as more precise gradations. This flexibility is one of the most useful aspects of Left/Right, since it can present a model with two fundamentally opposed sides, or with more nuanced positions within those sides as depending on the levels of disagreement over the core conflict.

Seventh and finally, it is worth noting that Left/Right may be put forward as an exhaustive description of politics; as a fragment of common sense it might be taken to apply to everything within politics. The ubiquity of Left/Right within the field of common sense about politics is likely, as noted above, to be related to its flexibility and its ability to incorporate many and varied referents – since the terms Left and Right are formally abstract they must be continually ‘filled in’ by historical content. In theory, therefore, Left/Right could potentially act as a description of all political events and actions within a given context; it would require, though, an additional claim that Left/Right was relevant to all dimensions of political life. It may be more common that it would be held to be the dominant one. Nevertheless, it is still an important point that there seem to be few political phenomena that are a priori not amenable to description in Left/Right terms and that a claim that politics is equivalent to Left/Right is at least in theory possible.

In sum, the language of Left/Right provides the formal limits on how Left/Right as a fragment of common sense can describe politics. A Gramscian approach to the analysis of common sense should attempt to specify these limits. Left/Right provides a set of resources and potential tropes for thinking about politics, and it should be emphasized that it is not the case that each dimension of the language of Left/Right must be foregrounded in every instance in which Left/Right is used in thinking about politics.

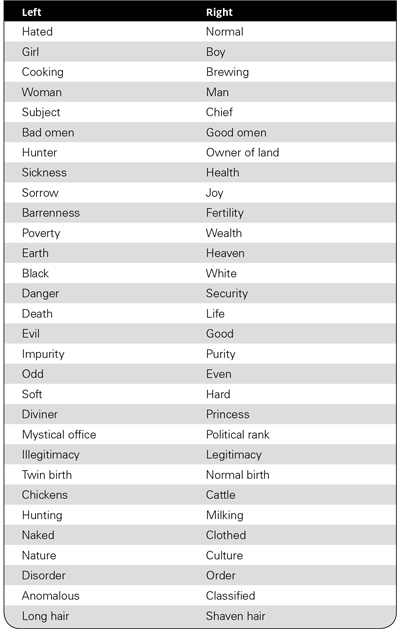

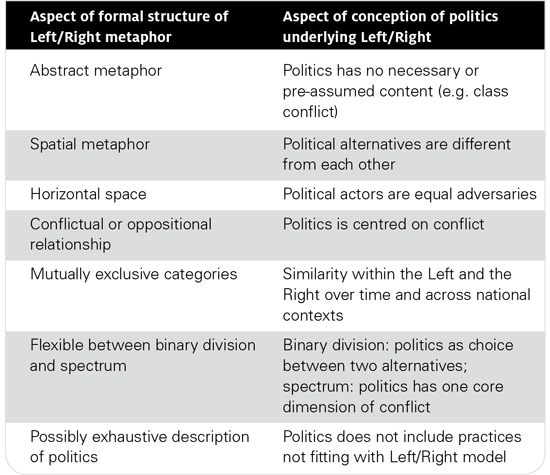

Even the brief analysis of the language of the metaphor of Left/Right in the previous section suggests that fragments of common sense that may appear simple can in fact be highly complex. Importantly, Gramsci held that ‘even in the slightest manifestation of any intellectual activity whatever … there is contained a specific conception of the world’.37 As a fourth step in the critical analysis of common sense, then, it is possible to investigate the ‘conception of the world’ that lies behind the formal structure of a fragment of common sense. Accordingly, we try to uncover behind Left/Right a more or less complete understanding of politics, and a privileging of certain ways of doing politics, which together form a ‘conception of politics’.

Our argument here is that each aspect of the language of Left/Right puts forward, in the guise of a description of politics, an assertion about what politics should be about or how politics should be done. In other words, the evaluative and the descriptive are very close together, such that a fragment of common sense that purports or appears only to describe a social phenomenon might also be giving a set of prescriptions about what that social phenomenon should be like. Table 6.3 illustrates our argument here. The aspects of the conception of politics put forward by Left/Right, when taken together, form something of the notion of the ‘conception of the world’ Gramsci saw as contained in every intellectual activity.

Table 6.3 The conception of politics underlying Left/Right

First, then, we can see that Left/Right as a fragment of common sense about politics does not assume any specific content of political conflict. Instead, specific positions must be constructed and named as ‘Left’ or ‘Right’. The criterion for the ‘legitimate’ use of the term ‘Left’ or ‘Right’ is then whether the interest or group that wants to assume that label – or is given that label by another political actor – adequately represents the heritage of legacy of the Left or the Right. What ‘the Left’ and ‘the Right’ struggle over is, importantly, left open.

Second, the spatial nature of the Left/Right metaphor suggests that the Left and the Right stand some distance from each other – if they are at the same point then the spatial metaphor loses all meaning. One way to illustrate this could be in terms of individual political attitudes towards redistribution of income led by the State.38 In this case it would be possible to establish one’s reasonably precise location on this spectrum. The grouping of individuals into Left/Right would then come from the calculation of the two local modal values. As a consequence, Left/Right as a common sense description of politics would tend simultaneously to constrain and to polarize differences, by grouping political actors around two poles. Those in the more central categories would be moved outwards to the Left or Right position and those in more extreme or peripheral categories moved inwards. The usefulness of Left/Right might be questioned, in this context, if all respondents were centrally positioned because then there would be no ‘distance’ between alternatives. With reference to the positioning of political parties or movements, Left/Right similarly suggests or creates political distance between two alternatives, while marginalizing extreme positions. At the same time, Left/Right seems to describe a politics of distinct alternatives, pushing the positions of Left and Right apart from one another in imaginative or political ‘space’. Importantly, if political positions converge in the centre of political space, then Left/Right becomes a less plausible common sense account of politics.

Third, Left/Right as a fragment of the common sense about politics is based on the postulation of a horizontal political space in which the Left and the Right appear as equals in a way that the centre and the periphery or the included and the excluded (or the higher and the lower) do not. The horizontal nature of the Left/Right metaphor may plausibly be seen as a claim about the validity of whatever conflict does exist: since the participants of the conflict are placed on the same plane, neither is advantaged and so the conflict is seen as ‘fair’ and as reinforcing the processes of mutual recognition that also provide the preconditions for conflict. In this sense, Left/Right as a fragment of common sense may be related to ‘democratic thinking’ within the political system through promoting a form of political conflict and debate based on a ‘principle of parity’ that supposes political adversaries are predisposed to solving conflict through democratic processes.39 At the same time, as noted above, the ‘Far Left’ and ‘Far Right’ groups that may be critical of the democratic political system are also marginalized by the description of politics in terms of Left/Right. Left/Right foregrounds an adversarial relationship as the central feature of the political process, standing as an attempt to legitimize conflict by describing it as legitimate.

Fourth, Left/Right as a fragment of common sense tends to promote political conflict, through the oppositional relationship between the Left and the Right, as central to the meaning of politics. Importantly, then, consensual political processes are de-emphasized by the commonsensical idea that ‘politics is about Left versus Right’. Left/Right, in other words, depends on the presence of political conflict to remain a tenable understanding of politics. Left/Right is likely to be heavily contested as part of the common sense of politics to the extent that societies enter a ‘post-political’ age in which consensus on the basic structure of society, as a form of welfare-state capitalism, has been achieved.40

Fifth, the Left and the Right are posited as mutually exclusive categories in a description of politics in terms of Left/Right (this point is related to the idea that Left and Right cannot occupy the same space within the metaphor). We can extend this idea by saying that there an additional assumption here, namely that the mutual exclusivity of Left and Right will be durable over time. In other words, Left/Right as a part of the common sense of politics is premised on the idea that the Left/Right metaphor will make sense tomorrow in the same way as it does today – that is, through the drawing of boundaries of mutual exclusivity. Left/Right thus tends to emphasize two aspects of the relationship between politics and time. First, stability in the terms of debate is assumed, in order that Left and Right mean comparable things over time. It is not necessary for Left and Right to mean exactly the same things. Second and relatedly, the model of Left/Right imposes similarity (at a given point in time) and continuity (over time) on all the movements described as ‘Left’ or ‘Right’, imputing a ‘family resemblance’ between past, present and future Lefts, and past, present and future Rights. The family resemblance, we can note, may also extend beyond national borders. In other words, the model of Left/Right puts forward the claim that politics should be about the over-time conflict between Left and Right and it accordingly imposes a long-term structure of two competing sides, which may tie together otherwise potentially quite disparate groups. In short, the model of Left/Right explicitly links contemporary political debates with those of the past, postulates complex links with other countries’ narratives and suggests similarity within the categories of Left and Right. For instance, seeing twentieth-century politics in Britain as comprehensible in terms of Left/Right tends to give prominence to long-term political divisions within British society, rather than those which may be more short-term. In addition, although it may not be an explicit move, British politics is placed in a specifically European context, rather than the liberal/conservative distinction that may instead situate British politics in relation to the American context.

Sixth, Left/Right is flexible between positing a binary division or a spectrum. To the extent that only two political categories are posited, Left/Right also excludes political positions such as ‘Centre’, ‘Centre-Left’ and ‘Far Right’, and marginalizes the ‘Far Left’ and ‘Far Right’ by attempting to assimilate them into the categories of Left and Right. In this case, the meaning of Left and Right is seen as core, with the ‘Hard’ Left or ‘Extreme’ Right as extensions of that meaning rather than anything qualitatively different or new. Therefore, the process of constraining political distance may be an important function of the political narrative of Left/Right, as well as the attempt to create it. A spectrum, on the other hand, might be seen as a way to understand a whole set of political positions or ideologies in relation to one another on the basis of a single dimension. That dimension is then put forward as central to politics, precisely because it allows us to understand the relative position of a range of political ideologies.41

Seventh, Left/Right may be put forward as an ‘exhaustive’ description of politics, in the sense that it applies to and explains all political conflicts within a given system. In this case, if a political practice or phenomenon does not fit into the model advanced, then it is excluded from the ‘normal processes of politics’. It this sense we might say that violence represents the breakdown of politics rather than its ‘continuation by other means’, suggesting both the limits to politics and the delegitimizing of violence to the extent that ‘politics’ is seen as a preferred human activity.42 Accordingly, the conception of politics underlying Left/Right tends to exclude from ‘politics’ those practices grounded in ‘illegitimate’ conflict or conflict between two undifferentiated adversaries. The former may be seen in a military coup, the latter in intra-party disputes or claims about the increasing similarity of policy programmes in contemporary politics and the falling back to managerial differences rather than ‘genuine’ political differences. The drawing of the boundaries of politics is an important part of any account of politics, and Left/Right stands as no exception, despite its apparently simple nature as part of the common sense of politics. We can see the process of exclusion at work in Left/Right in two further ways. First, a group which does not accept the validity of its opponents or the rules of the democratic game may be marginalized or, at most, excluded from ‘politics’ to the extent that the model of Left/Right is argued to necessitate the mutual recognition of the adversaries within a conflictual relationship. Second, to rephrase a point made above, we can see exclusion also as the reverse of the creation of political space. In other words, since Left and Right represent the limitations of political space, anything outside of the furthest boundaries of the Right is either drawn into the Right, having its differences elided, or is ‘excluded’ from the Left/Right model. Thus, a central function of Left/Right as a fragment of common sense about politics, most strongly but not exclusively put forward in claims about its exhaustiveness, is the drawing of boundaries. Specifically, in this case, the boundaries concern which practices and what orientations to political adversaries count as properly political and which do not.

In sum, we can categorize the conception of politics underlying Left/Right in the following way. Left/Right is premised on, and tends to reinforce, an understanding of politics based on conflict, and specifically a conflict in which two equal antagonists present clearly differentiated (or ‘distanced’) political alternatives, and then engage in a encounter of equals to determine the side that will be victorious. Importantly, Left/Right as a fragment of the common sense of politics does not impute any necessary or pre-assumed content to the conflict. At the same time, the politics of any national context are linked to past conflicts between the Left and the Right (as far back as revolutionary France) and also to conflicts in other national contexts, perhaps particularly those of continental Europe. A Left/Right understanding of politics is also premised on a conception of politics that excludes consensual practices and marginalizes extreme positions. We can thus see that an analysis of the formal structure of Left/Right shows it to be based on a surprisingly developed and sophisticated conception of politics. Following Gramsci, we take this as support for the proposition that fragments of common sense are likely to contain within them a conception of the world; it is the task of those who would engage in the critical analysis of common sense to reveal these conceptions of the world and try to map something of their complexity.

The critique of common sense: Interpreting Left/Right as a political narrative

The fifth step in the methodology of the critical analysis of common sense that we have been developing in this chapter involves the interpretation and critique of a given fragment of common sense as a story about society. Specifically, the conception of the world underlying the fragment of common sense under investigation, as following from a close analysis of the formal structure of a contextualized and historicized fragment of common sense, should be compared to the conception of the world of the philosophy of praxis. Accordingly, in this section we attempt in a tentative way to compare the understanding of political conflict contained in the Left/Right metaphor with a conception of class struggle.

The first part of this argument involves extending Gramsci’s thought by suggesting that Left/Right might illustrate one of the characteristic ways in which common sense makes sense of the social world: through the telling of stories. Here we suggest that Left/Right can be understood as a story about politics or a political narrative.

Above all, Left/Right is a stylized way of understanding politics, and one in which contemporary debates of Left against Right are compared to older ones in the attempt to establish over-time continuity and offer an interpretation of contemporary conflict. In the straightforward sense of providing an account of the relationship of historical events, Left/Right stands as a narrative. In addition, if we think of ‘narrative’ in the most general terms as a relayed account of connected events, then it becomes hard to deny that Left/Right is one of the great organizing narratives of modern politics.

Telling stories, including those about politics, is a pervasive and important human activity. It is part of common sense as a way of making sense about politics. The term political narrative here means, in the first instance, just the stories we tell about politics. We see the telling and re-telling of political narratives as something in which we all engage, and as a reflection of the complexity and creativity of everyday thinking about politics. A concept of political narrative may allow us to begin to conceptualize the ways in which our everyday thinking about politics is an important moment in the construction of ideologies.

Immediately, though, the question is raised of how we can assess the story of Left/Right. Interestingly, the anthropologist Clifford Geertz writes, ‘Like Lear, the New Testament, or quantum mechanics, common sense consists in an account of things which claims to strike at their heart. Indeed, it is something of a natural rival to such more sophisticated stories when they are present, and when they are not to phantasmagoric narratives of dream and myth.’43 We might suggest that Geertz’s understanding of common sense captures much of the authority of Left/Right: Left/Right presents an account of things which claims to strike at their heart, and in popular accounts of politics this manifests itself as the political narrative that ‘Politics is about Left versus Right’. It is not so much, therefore, that Left/Right is true or false, but that it is a useful, compelling, accessible, stylish and exciting story. It does not rely on being true but rather on its narrative qualities, which are much more difficult to define and point out. It is thus of interest to assess the characteristics by which we accept or reject stories about politics.

One advantage to seeing Left/Right as a story about politics is that it opens up a variety of new research methods and perspectives in the examination of common sense. In particular, one method of the interpretation of narratives involves our ‘re-reading’ them in the terms of another narrative. A potential model for this ‘re-reading’ process is Fredric Jameson’s influential understanding of the interpretation of narrative from The Political Unconscious (1981), in which a given narrative is understood – in addition to other elements of an analysis – in its relationship to a master narrative.44 For Jameson, this master narrative, which defines the terms with which we re-read other narratives, is ‘class struggle’. Jameson’s model might add an important additional dimension to our historicized understanding of Left/Right as common sense. The second part of our argument here thus involves comparing the conception of politics underlying Left/Right with a notion of class struggle, in order to provide a critique of Left/Right as a fragment of common sense.

Explicitly relating the conception of political conflict underlying Left/Right to a conception of political conflict as class struggle provides a whole range of basic insights about its role as a political narrative. Left/Right postulates a division at one level – Left/Right – that is contained within a unity at a higher level: whatever it is that is split between Left and Right. Suggested here are conceptions of the nation, or perhaps an overarching consensus in which Left and Right compete. By basing itself on difference, it prompts the question of what allows us to group together those elements divided on the basis of Left and Right. One suggestion might be ‘liberal democracy’ or ‘bourgeois democracy’. To the extent, then, that Left/Right may be thought of as a division between two halves of liberal democracy, it might be rejected as a distinction without a difference. Moreover, we can see that the idea of Left/Right is fundamentally different to that of class conflict for a number of reasons. For instance, ‘Workers Versus Capitalists!’ is an entirely different sort of narrative, as both its antagonists are historically generated and, even more crucially, the solution of the opposition is only possible historically through a movement from present society to a qualitatively different one. The substitution of a social contradiction between classes for a surface opposition between groups is an important function of the political narrative of a conflict between the Left and the Right. Thus, Left/Right may be the capitalist common sense of politics par excellence: it was not only initially generated by a developing capitalism in the context of debates within the bourgeoisie over the nature of its political freedoms, but it also disguises this fact and ideologically masks a deeper, more generative and less resolvable conflict: that between the minority of capitalists and the majority of workers. Therefore, Left/Right as a common sense story about politics offers a formal and aesthetic resolution of the contradictions between classes in capitalism. The ‘resolution’ in this case takes the form of a postulation of formally empty and ahistorical conflict between Left/Right and the obfuscation of the deeper class conflict of between labour and capital. Even if, of course, class actors come entirely to embody the two poles of the conflict, the historicity of the factors generating the conflict in the first place is effaced. Left/Right presents itself as a ‘pristine’ political division: the notion of contradiction (which cannot be resolved) is reduced to one of opposition. ‘Labour versus capital’ does not suggest the equality of adversaries, nor mutually agreed rules of engagement. The implicit suggestion of the reconcilability of the Left and the Right – they are positional, and have moved in the past and so may move ‘toward’ each other in the future – is based on a specific view of conflict. This is a crucial insight to be gained from seeing Left/Right as a story told about politics, and therefore as open to different types of interpretive analysis.

Importantly, conflict between the Left and the Right is seen as a political conflict rather than one based on economic or class factors. Accordingly, ‘the Left’ has denoted a succession of groups that struggled, successively, for political rights, for class interests and for social rights.45 ‘The Right’, on the other hand, has referred to a heterogeneous set of responses to the Left and political groups, including the reaction to the French Revolution; the moderate Right of Burke, de Tocqueville and Constant; the response to socialism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; the extreme Right of nationalist and anti-immigration parties in Europe from the end of the twentieth century; and, most recently, the neo-conservative and neo-liberal New Right.46 Also, we can note that Left/Right conflict is seen as equal, both as between equals and also balanced. However, the conflict between ‘the people’ and ‘the monopolists’, to take a Popular Front slogan, or the conflict between the ‘1%’ and the ‘99%’ are both deliberately unbalanced to show that in fact the conflict is precisely between a majority and a minority. Alternatively, ‘workers’ versus ‘capitalists’ may suggest that the latter may be more financially powerful than the former, opposing one side of the struggle’s power with the other’s numerousness. Finally, the conflict between Left and Right is static, since there is nothing internal to either that suggests a third unifying or transcending category: the Centre is exactly between Left and Right, and it requires a complex ideological construction to oppose ‘forward’ to Left/Right.47 Importantly, the conflict is not going to be ‘resolved’ or ‘transcended’ by either the Left or the Right, since both antagonists remain within the terms of Left/Right conflict.

This chapter has aimed to show that Gramsci’s thought on senso comune can be developed through the detailed examination of a specific ‘fragment’ of common sense, namely Left/Right as part of the common sense of politics.48

We have hoped to show that common sense is composed of immensely complicated thought-products, and that these thought-products warrant serious attention from those interested in developing Gramsci’s thought today, and perhaps within the field of political theory more generally. We have suggested that Left/Right as part of the common sense of politics stands in a set of complex relations to Left/Right as a general way of making sense of the world, has a complex and multifaceted history, exhibits an interesting and complicated formal structure, contains within it a conception of the world and acts as a story about politics – or a political narrative – that can ultimately be subjected to critique through a process of interpretation that involves relating it to class struggle. This five-part methodology is proposed as usable by anyone who might wish to investigate common sense.

In theoretical terms, we have suggested that Gramsci’s ‘philosophy of senso comune’ might be extended by seeing fragments of common sense as part of the process of telling stories to make sense of our world and our place in it. Common sense might not have to be straightforwardly ‘true’ to be successful but instead might gain traction by providing a compelling, interesting or useful story. The tools of literary theory might then be relevant to the difficult analytical task of examining common sense as it actually exists and linking it to the forms of hegemony that exist in a given society at a given point in time. Finally, Gramsci’s philosophy of senso comune in general warrants more attention from scholars interested in Gramsci. Extending the philosophy of senso comune could involve thinking about what it might mean for common sense to be our ‘sixth’ or social sense, a critical way we have of ‘making sense’ of the world. Linked to this idea is Marx’s claim in his Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 that our senses are social, and that the forming of the (five) senses is a ‘labour of the entire history of the world down to the present’.49 We might then extend Gramsci’s thought by considering that senso comune might not be just a product of ways of making sense of the world but could instead be a mode of perception of the social, at once foundational and deceptively complex.

1 See Kate Crehan, ‘Gramsci’s Concept of Common Sense: A Useful Concept for Anthropologists?’, Journal of Modern Italian Studies, 16:2 (2011), pp. 273–87; Landy, Film, Politics and Gramsci; Guido Liguori, ‘Common Sense in Gramsci’, in: Joseph Francese (ed.), Perspectives on Gramsci: Politics, Culture and Social Theory (London: Routledge, 2009), pp. 112–33; José Nun, ‘Elements for a Theory of Democracy: Gramsci and Common Sense’, Boundary 2, 14:3 (1986), pp. 197–229; Andrew Robinson, ‘Towards an Intellectual Reformation: The Critique of Common Sense and the Forgotten Revolutionary Project of Gramscian Theory’, Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy, 8:4 (2005), pp. 469–81. A partial exception from this pattern is Evan Watkins’s ‘Gramscian Politics and Capitalist Common Sense’, Rethinking Marxism, 11:3 (1999), pp. 83–90. There Watkins attempts to investigate the common sense of economic relations in the United States in late 1990s, although he does not look either to analyse in detail the common sense he outlines, or to develop a systematic methodology for the analysis of common sense.

2 Q11§13; SPN, p. 419.

3 Peter Mair, ‘Left-Right Orientations’, in: Russell Dalton and Hans-Dieter Klingemann (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Political Behaviour (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), pp. 206–22.

4 Russell Dalton, ‘Social Modernization and the End of Ideology Debate: Patterns of Ideological Polarization’, Japanese Journal of Political Science, 7:1 (2006), pp. 1–22.

5 Kenneth Benoit and Michael Laver, Party Policy in Modern Democracies (London: Routledge, 2009).

6 Juan Laponce, Left and Right: The Topography of Political Perceptions (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1981).

7 Alain Noël and Jean-Philippe Thérien, Left and Right in Global Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), p. 10.

8 Ferenc Feher, ‘1989 and the Deconstruction of Political Monism’, Thesis Eleven, 1:42 (1995), pp. 87–112; Steven Lukes, ‘Epilogue: The Grand Dichotomy of the Twentieth Century’, in: Terence Ball and Richard Bellamy (eds), The Cambridge History of Twentieth-Century Political Thought (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), pp. 602–26.

9 Norberto Bobbio, Left and Right: The Significance of a Political Distinction (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1996), p. 1.

10 Steve Bastow and James Martin, Third Way Discourse: European Ideologies in the Twentieth Century (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2003), pp. 23–4.

11 Mair, ‘Left-Right Orientations’, p. 206.

12 Schwarzmantel argues that the period in which Left/Right was the dominant model of politics can be clearly identified: the ‘age of ideology’ from the revolutions of 1776 and 1789 to the end of modernity. The division of political conflict along Left/Right lines is thus related to difficult and important questions of the periodization of contemporary history, and in particular whether we have reached a period beyond the modern in which traditional identities and maps such as those based on the Left and the Right need to be discarded. See John Schwarzmantel, The Age of Ideology: Political Ideologies from the American Revolution to Postmodern Times (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1998).

13 See Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism (London: Zer0 books, 2009).

14 David Crow, Left to Right: The Cultural Shift from Words to Pictures (London: Thames and Hudson, 2006).

15 James Hall, The Sinister Side: How Left-Right Symbolism Shaped Western Art (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008).

16 Lukes, ‘Epilogue’, p. 603.

17 See Rodney Needham (ed.), Right and Left: Essays in Dual Symbolic Classification (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1973).

18 See Rodney Needham, ‘Right and Left in Nyoro Symbolic Classification’, in: Rodney Needham (ed.), Right and Left: Essays in Dual Symbolic Classification (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1973), pp. 299–341.

19 Chris McManus, Left Hand, Right Hand (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2002), p. 39.

20 Ibid., p. 17.

21 Piero Ignazi, Extreme Right Parties in Western Europe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), p. 7.

22 Alain de Benoist, ‘The End of the Left-Right Dichotomy: The French Case’, Telos, 1:10 (1995), pp. 73–89.

23 David Caute, The Left in Europe since 1789 (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1966), p. 26.

24 Ignazi, Extreme Right, p. 8.

25 See Caute, The Left in Europe, p. 26.

26 Lukes, ‘Epilogue’, p. 606.

27 Ibid., p. 606.

28 Marcel Gauchet, ‘Right and Left’, in: Pierre Nora (ed.), Realms of Memory: Rethinking the French Past, Vol. 1: Conflicts and Divisions, translated by Arthur Goldhammer (New York: Columbia University Press, 1996), p. 248.

29 See Stefano Bartolini, The Political Mobilization of the European Left, 1860–1980 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000).

30 Lukes, ‘Epilogue’, p. 606.

31 Ignazi, Extreme Right, p. 5.

32 Samuel Brittan, Left or Right: The Bogus Dilemma (London: Secker and Warburg, 1968), p. 38.

33 Dieter Fuchs and Hans-Dieter Klingemann, ‘The Left-Right Schema’, in: M. Kent Jennings and Jan W. van Deth (eds), Continuities in Political Actions (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1990), p. 206.

34 Torben Beck Dyrberg, ‘The Democratic Ideology of Right-Left and Public Reason in Relation to Rawls’s Political Liberalism’, Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy, 8:2 (2005), pp. 161–76.

35 Torben Beck Dyrberg, ‘What Is Beyond Right/Left? The Case of New Labour’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 14:2 (2009), pp. 133–53.

36 Lukes, ‘Epilogue’.

37 Q11§12; SPN, p. 323.

38 See for instance Geoffrey A. Evans, Anthony F. Heath, and Mansur Lalljee, ‘Measuring Left-Right and Libertarian-Authoritarian Values in the British Electorate’, British Journal of Sociology, 47:1 (1996), pp. 93–112.

39 Lukes, ‘Epilogue’.

40 See for instance Anthony Giddens, Beyond Left and Right (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1994); Ulrich Beck, World Risk Society (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1999).

41 One possible extension of this idea then becomes the ‘horseshoe’ description of Left/Right: the far Left’s and far Right’s totalitarianism (or other characteristic) actually distorts and bends the entire horizontal space of Left/Right, such that, for instance, supposed similarities between fascism and communism are emphasized.

42 See Hannah Arendt, On Violence (London: Allen Lane, 1970).

43 Clifford Geertz, ‘Common Sense as a Cultural System’ in his Local Knowledge: Further Essays in Interpretive Anthropology (New York: Basic Books, 1983), p. 84.

44 Fredric Jameson, The Political Unconscious: Narrative as a Socially Symbolic Act (London: Routledge, 1981).

45 Eric Hobsbawm, ‘What’s Left of the Left?’ in his The New Century: In Conversation with Antonio Polito (London: Abacus, 2000), pp. 95–116.

46 Roger Eatwell, ‘The Right as a Variety of “Styles of Thought”’, in: Roger Eatwell and Noël O’Sullivan (eds), The Nature of the Right (London: Continuum, 1989), pp. 62–76.

47 See Bastow and Martin, Third Way Discourse.

48 Subsequent steps in the investigation of Left/Right as part of the common sense of politics might be as follows: an investigation of the groups in a specific national context that use the label ‘the Left’ or ‘the Right’ and how they use this label; an attempt to chart the use of Left/Right in politics textbooks, divided by subject, and how this piece of common sense provides the starting point for more complex explanations of politics, as reaching towards the ‘upper level of philosophy’ of accounts of politics given by political scientists; an attempt to map the use of Left/Right in concrete examples of popular political commentary, paying close attention to how it functions in different cases and whether there might be a pattern to any differences that the material reveals; and the comparison of Left/Right as part of the common sense of politics with other important stories about contemporary politics, perhaps starting with the notion that ‘there is no alternative’ to today’s liberal capitalism.

49 Marx and Engels, Collected Works, vol. 3, p. 302.