THE ATLANTIC SLAVE TRADE AND THE COLUMBIAN EXCHANGE

Starting in the 1490s, the Iberian (Spanish and Portuguese) scramble to exploit the land and labor of the Americas led to cross-cultural contacts among Amerindians (Native Americans across the American continent), Europeans, and Africans. This led to the creolization, or mixing, of cultures, as Europeans, Amerindians, and Africans interacted for the first time in the New World. The environment (topography, climate, etc.) and the availability of plants, animals, and fish both influenced the creolization process through the creation of regional differences. Other factors that affected creolization included contact with Europeans and Africans before and during the Middle Passage (travel from Africa to the Americas); a sense of self-identification as Africans with distinctive traditions; access to plants, animals, and fish; and group size and class status upon arrival. Because creolization was often an involuntary process, the effect of these influences on each individual varied.1

In the fifteenth through seventeenth centuries, there was a great deal of creolization and other ethnic mixing in the Atlantic world. African American cuisine—what African Americans in the 1960s would later call “soul food"—developed from a mixing of the cooking traditions of West Africans, Western Europeans, and Amerindians.2 Historian Douglas Brent Chambers has shown in the case of the Igbo in Virginia that, contrary to popular belief, Africans in the New World did not face an entirely different environment: they had been introduced to American plants before their forced migration to North and South America and in general would have been “operating within a basically familiar agriculture” in colonial America. Vegetables that African Virginians grew that were common to Igboland were kale, cabbages, mustard leaves, black-eyed peas (cowpeas), gourds, okra, spinach, squash, watercress, watermelon, yams, corn, pumpkins, and peanuts. These “were indigenous to the Americas but had been incorporated by people of Igboland probably by the early or mid-17th century.” Yams, eggplants, bananas, plantains, rice, millet, cassava/manioc, and Melegueta peppers are other examples of African food crops in the era of the slave trade.3

Between 1450 and 1600, the Portuguese built trading posts on the west coast of Africa and slave labor sugar plantations on the African island of São Tomé in the Gulf of Guinea.4 By the sixteenth century, the Spanish had established settlements in the Americas. On the African, European, and American continents, the majority of people shared a preference for preparing soups, stews, and breads; their diet consisted largely of grains. The African and Amerindian diets contained far more vegetables and legumes than the Europeans consumed. Many of the innovations in Atlantic foodways, particularly the introduction of exotic ingredients from the East, occurred as a result of years of cultural imperialism by foreign invaders.5 Before 1000 B.C., North Africans and Celts settled the Iberian Peninsula. Phoenicians, Greeks, Carthaginians, and Romans controlled the region between 201 and 400 A.D. Ingredients found in Spanish dishes, such as olive oil, garlic, and pulverized almonds, were introduced by the Romans during this period. Seizing power in 711 A.D., the Moors ruled parts of Spain and Portugal for some eight hundred years; their cuisine had a great influence on Iberian kitchens.6

The Moors introduced into Iberian cookery a number of spices and herbs obtained through the Arabian spice trade. Before the European re-conquest of the peninsula in 1492, the Moorish preference for cooking with liberal amounts of onions, garlic, and buttermilk dominated the Iberian world. Moorish cooks used cinnamon, cumin, turmeric, paprika, sesame seed, black pepper, cloves, and coriander seeds, among other spices. They were also knowledgeable about cooking with parsley, green coriander, marjoram, mint, and basil. Moorish seasoning techniques called for using spices and herbs to enhance, not dominate, the flavor of vegetables, fish, poultry, and red meat.7 These spices and cooking philosophies of Moorish and Iberian origins became important in African cookery.

Several traditions that have influenced southern African American cooking can be traced back to the Arawak people of the Caribbean. The greatest concentration of Arawak islanders was within the larger Caribbean islands of Cuba and Hispaniola. The Arawak-Carib diet consisted of a lot of non-sauce barbecuing of meat on green wood grills called brabacots. The Spanish translated the word to barbacoa, from which came the English word “barbecue.”

When the Spanish migrated to the Caribbean in the sixteenth century, they imported food and livestock from Europe.8 For instance, they introduced peaches—of Persian origin—to the Americas, where the indigenous peoples cultivated them and popularized their consumption. The Spanish also imported large numbers of domesticated pigs and hens. Because the islands had no predators and there were many root crops to graze, the pigs thrived. Europeans quickly learned from locals how to smoke and barbecue pig meat. In 1555 one traveler described the residents of Santo Domingo as having great quantities of pork and poultry. The pork, he wrote, was “very sweet and savoury; and so wholesome that they give it to sick folks to eat, instead of. . . poultry.”9

In addition to importing livestock, Columbus introduced sugarcane to the Americas on his second voyage in 1494. The Spanish cultivation of sugarcane in the Caribbean eventually led to the growth of the Atlantic slave trade and the importation of large numbers of West Africans. During the early stages of the Atlantic slave trade, eating traditions were exchanged as transatlantic links developed among European, African, Arab, and Asian traders.10 Many of the eating traditions that shaped African American eating habits originated in West African cultures.

AFRICAN COOKERY

West African cooking (within the region presently made up of the republics of Senegal, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Gambia, Liberia, Ivory Coast, Ghana, Dahomey, Togo, Nigeria, Cameroon, and Gabon) between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries remained “unmodified by European influences,” writes one African American cookbook author.11 I disagree and show instead that African cookery was significantly transformed by such influences, in large part stemming from the commerce that began as a result of, first, the Columbian exchange and, second, the African slave trade. Iberians introduced maize (as well as manioc) and new domesticated animal species, which increased the usage of fowl and pork in African kitchens. These introductions made notable and long-lasting changes in African cooking. African societies, according to one scholar, “absorbed and utilized new crops” such as corn and sweet potatoes “to support or to replace the basic diet.” Arab traders, Indonesian islanders, and European slave traders all introduced foreign foods to Africans, who quickly made them a part of their diet.12

The Islamic religion’s restrictions on pork consumption did have sway in some sections of West and Central Africa, but, for the most part, the influence of the religion did not hinder increased pork consumption. Among the Hausa of precolonial northern Nigeria, Islam was primarily an “urban phenomena.” Islamic Africans made up just 10 percent of those shipped to North America, making their influence rather minuscule.13 In certain regions of Africa (urban areas without Islamic authorities and rural areas less affected by Islam), West and Central Africans viewed pork as a great delicacy, and African women prepared various parts of the hog for consumption. We know, for example, that pig meat was in high demand in Catholic-influenced Mozambique, where the Portuguese established a strong presence in the fifteenth century. The Dutch explorer Pieter de Marees tells us that, in Mozambique, pork was “as great a delicacy as Chickens” and was “given to sick people as food, instead of Chicken.”14 In addition to pork and fowl, the Portuguese introduced American vegetables to African farmers, particularly sweet potatoes and maize.

Previous to the arrival of the sweet potato, most West Africans used yams in the absence of bread. Soon many other substitutes were available. Indonesian traders introduced bananas, plantains, and the cocoyam from Southeast Asia; shortly thereafter, all three became part of the everyday meals of West Africans. This was especially pertinent in the equatorial forest regions. Because yams were such an essential part of this region’s culinary traditions, some nicknamed it the “yam belt.” As for plantains, we know that African cooks regularly ate roasted green plantains (and bananas). When the Atlantic slave trade introduced corn and sweet potatoes to Africa (along with other American crops such as pumpkins and cassava), the Portuguese used them to provision their slave-trading vessels.15

By the nineteenth century, the Igbo and Hausa people had incorporated corn and sweet potatoes into their fields. A similar transformation occurred among the Fulani. In northern Angola and the western Congo, it proved easier to grow and cultivate than indigenous crops (such as sorghum, millet, teff, and couscous [semolina]) during environmental catastrophes like locusts and flooding. It was not long before bread made with corn and sweet potatoes became the staple food of poor people in parts of Central Africa.

By the 1600s, de Marees observed women in the Congo making bread from both corn and millet: “In the evening they put this grain [millet] with a little Maize into water to soak. In the morning . . . they take this Millie and put it on a Stone such as the Painters use to grind their Paint. Then they take in their hand another stone, about a foot long, and grind this Millie as fine as they can, till it becomes Dough and looks almost like baked Buckwheat Cakes. They mix this Dough with fresh water and Salt and make it into Balls the size of a couple of fists. They lay these on a warm floor where they bake a little; and this is the bread they eat.” 16

De Marees goes on to describe how women on the coast of Guinea accumulated capital selling corn bread to Portuguese enclaves in Angola and on the sugar-producing island of São Tomé. Calling them “the Negroes of the Castle Damina,” he recalled how they made a popular maize bread called Kangues that sold well in local markets in coastal Guinea. The bread was made by wrapping the corn-based dough in a banana leaf and placing it under the cinders of a fire.17 The bread was excellent, but it also sold well because the women had perfected a recipe that allowed it to be kept for several months, making it a perfect staple for the slave traders’ long sea voyages.

West Africans were already cultivating two types of rice (one coarse and red, the other very small and white), when the Portuguese introduced Asian rice from the Far East. This most likely complemented rather than replaced the indigenous varieties. Groups between Cape Verde and the Gold Coast cultivated large amounts of rice. In fact, they cultivated so much of it that they became known as the people of the Rice Coast.18

In addition to corn, rice, and sweet potatoes, foreign traders introduced a new species of hen to West Africans.19 The Guinea hen was perhaps the most important foreign animal introduced to Africa. The lean and dry meat of this game bird was considered superior to chicken and pheasant. Arab traders introduced it principally to cattle-raising societies like the Fulani of northern Nigeria. The Fulani mastered the art of raising large flocks of Guinea hens in the grasslands where they flourished. West Africans also incorporated the Guinea hen into many of their religious celebrations. The point here is that Africans were familiar with frying, baking, and making soups and stews with poultry before they arrived in colonial America.20

As mentioned, the Igbo and Mande were among the largest ethnic groups first to arrive in colonial Virginia, the West Indies, and the Carolinas. Information on the Igbo and Mande comes from the travel accounts of Europeans who explored the Congo, Guinea, Gambia, Ivory Coast, Ghana, and Nigeria. Although these authors were admittedly Eurocentric in their worldviews, they provide insightful descriptions of Igbo and Mande cooking.21

Along the Gold Coast, the Dutch explorer William Bosman identified West African societies as divided into five distinct groups: kings, chiefs, noblemen, commoners, and slaves.22 Power came from controlling trading towns and cities, gold- or ivory-producing areas, the river tributaries, and trade routes across the Sahara that linked West Africans, Arabs, and Berbers. West African kings had two sources of revenue. First, traders paid royal tax collectors a percentage of their goods for the right to bring goods in or out of the empire. The second source was slavery: After 1600 West African kings made fortunes from the profits of slave traders who supplied European planters in the Americas with African slaves.23 The intercontinental slave trade in Africa also provided the families of kings, chiefs, and noblemen with female cooks and kitchen staff. In precolonial northern Nigeria, almost half the population was enslaved. Slavery dominated the entire economy of the region, with the plantation sector absorbing the majority of slaves within most slave societies. The remaining slaves worked in the households of elites.24

Among commoners, female elders put a premium on teaching young girls within their families how to cook. A girl’s mastery of cooking improved a common family’s chances of obtaining a prosperous marriage alliance with a groom of some social standing. The female toddlers of commoners accompanied their elders into the forest to fish and to gather berries, herbs, tubers, mushrooms, and wild greens. Thus, at a very young age, African girls from nonelite family compounds learned how to live off the land. As the daughters of farmers and herdsmen, they foraged to supplement what the men produced and hunted. In West Africa, women gathered “bush greens,” different varieties of spinach, collards, mustard greens, and the leaves of root vegetables like yams. They used them raw or in cooked vegetable dishes.25

The African cook used pieces of meat and fish as seasoning when he or she had access to them. Historian Robert W. July writes: “Protein deficiency, endemic in the yam belt, led to a general craving for meat, which in turn widened the limits of what was conventional fare.”26 Another researcher found that meat most likely represented “only a relatively minor part” of the commoner’s diet in West Africa and the Congo. West Africans obtained meat from hunting if they lived in forest regions. Those in coastal regions consumed large quantities of fish, both fresh- and saltwater. Fish and oysters contributed essential protein to the commoner’s diet.27 Tradition in both forest and coastal societies obliged the head woman of a family compound to provide food and cook for her husband’s relatives and friends. Family compounds consisted of one’s immediate and extended family, including grandparents, aunts and uncles, cousins, and their offspring. A village comprised several family compounds.28

IGBO TRADITIONS

The terms Igbo and Mande refer to two large families of languages spoken by a great number of West African ethnic groups and to the geographic areas they occupied. As mentioned, the Igbo originally settled in the northern part of the Niger River delta in what is today the Biafra region of Nigeria.29 Igboland was the center of yam agriculture. “Igbo peoples were the yam growers par excellence in West Africa,” according to historian Douglas Brent Chambers. Next to the yam in importance was the expressed oil of the African palm, which was used for frying and to make yam foofoo (a doughy paste made from pounded yams soaked in palm oil) and to flavor soups and stews. In addition, the bitter-tasting kola nut, which contained caffeine, was highly prized and served to guests. It would later be used as an essential ingredient in the original Coca-Cola soft drink recipe. Other important Igbo staples included rice, millet, and okra, used to thicken soups and stews. The Igbo also cultivated greens, watermelons, black-eyed peas (cowpeas), pumpkins, and gourds and raised domesticated animals for milk and meat consumption.30

The use of yam foofoo as bread and the palm tree for various food preparations is typical of Igbo cooking.31 Explorer Joseph Hawkins observed that “if they possess rice, roots, and palm wine, a cow, a few goats or sheep, to afford them occasionally milk or meat, to feed themselves and entertain their friends, they enjoy consummate happiness.” After the arrival of foreign traders, Igbos began raising and using corn as well as manioc and sugar. These adopted crops served as a complement to a yam-based diet rather than a supplement. In 1796 Hawkins recalled that Igbo fields had “a considerable quantity of large species of millet,” manioc, sugarcane, and the “finest maize I had ever beheld.” He also observed goats and sheep grazing in rich “pastures as far as the eye could reach.”32

In 1796 the subsistence farming performed by the Igbo in the tropical climate ensured that community members regularly had plenty of healthy physical activity. Woman worked in the fields, pounded yams into foofoo and grains into flour, hauled water for cooking, and cooked for hours at a time in hot kitchens. Men, writes Hawkins, used knives “six to eight inches long” for everything from cutting timber, cleaning animals, and preparing plant foods to “digging, turning up the soil, sowing or reaping the crop.”33 Members of the Igbo communities located along the mouth of the Gambia and Niger rivers regularly engaged in hours of physical activity, maneuvering boats, casting and hauling in fishing nets, and processing their catches. With so much daily physical activity and the regular consumption of high-fiber and raw foods, obesity was apparently no problem among the Igbo.

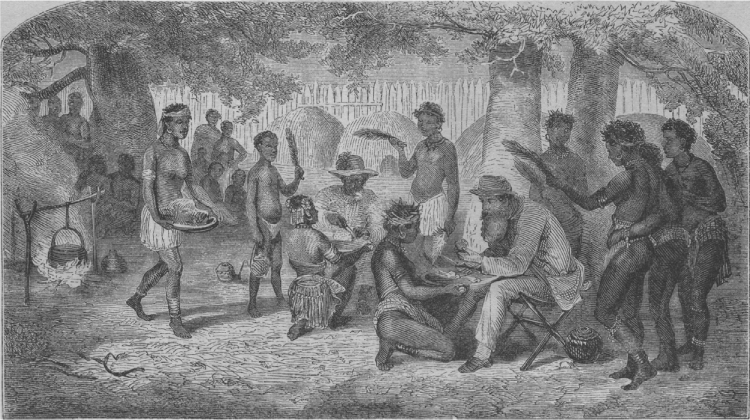

FIGURE 1.1 “Dining with Kaffr Chief.” Picture Collection, The Branches Libraries, New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.

The Igbo were familiar with cooking various types of fish and poultry in West Africa that they would later find when they arrived in the Chesapeake Bay. According to Hawkins, the rivers in Igboland were full of “lobsters, crabs, prauns, cray-fish, soles, mullets, &c. in great abundance while the thickets on their banks, afford the GUINEA-HEN, the MOOR FOWL, the ORTOLAN, and innumerable others.”34 Igbo hostesses also prepared an animal that in appearance looked like an opossum. “In shape and colour it resembled the OPOSSUM, except that it had no pouch or false belly; the hair also was much shorter—however, when dressed, it tasted deliciously,” recalled Joseph Hawkins.35 In short, Igbos cooks did not have that much adapting to do when they arrived in America. They had only to find an alternative to palm and kola nut oil for frying fish and poultry and making soups and stews in the Chesapeake Bay region.

Like the Igbo, the Congolese also cooked with palm oil, serving it with boiled rice and millet seasoned with a little meat, poultry, or fish. “The oil is so essential an article of food,” observed Hawkins, “the Africans employ it in all their meals, with yams, rice, millet, fish, and even with beef and mutton.”36 Mullet dipped in a “palm-oil and hot pepper marinade” and then dried and smoked over a hot fire was a staple among coastal dwellers. On special occasions, like the arrival of foreigners, the Congolese entertained at banquets offering rice, roasted and dressed venison, fowl, and milk.

An Igbo hostess also cooked stewed meat and duck but served it with foofoo instead of rice. Cooks usually served stews in a calabash platter containing a large loaf of warm yam foofoo. The diners then squatted around the communal calabash taking turns breaking off a lump of foofoo with their fingers and rolling it into a ball. This was then soaked in the hot palm oil containing floating bits of meat and vegetables. Igbo people also used foofoo-covered fingers like forks or spoons to eat other stewlike dishes.37

MANDE TRADITIONS

Mande speakers (identified in the primary sources used here as Mandingo and Mandinka) lived in the geographic area of the present-day countries of Burkina Faso, Senegal, Gambia, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia, the Ivory Coast, and Ghana, among others. As largely subsistence farmers and rice eaters, the Mande people, according to the expeditions in the 1790s of the twenty-four-year-old Scottish explorer Mungo Park, performed their daily share of physical activity, thus staving off obesity. “Few people work harder, when [the] occasion requires, than the Mandingoes,” recalled Park.38 The vast majority of their time was spent cultivating rice, couscous, a variety of vegetables, including corn, and the shea tree (whose fruit is crushed and boiled to produce shea nut butter). “The labours of the field,” writes Park, “give them pretty full employment during the rains; and in the dry season, the people who live in the vicinity of the large rivers employ themselves chiefly in fishing. . . . Others of the natives employ themselves in hunting.” We know from Park that before they arrived in the Carolinas and other parts of the Southeast the Mande hunted squirrels, “Guinea-fowls, partridges, and pigeons,” foraged for insects, and raised milk-producing cattle. Park also recalls that a mainstay of the everyday Mande diet consisted of bowls of rice and couscous cooked with milk (or water) “flanked by copious bowls of cream and honey.”39 Again, the culinary transition that came with slavery in America was not drastic.40

By the nineteenth century, the Mande, like the Igbo, had fully introduced corn into their daily diets. A vivid description of how Mande women processed corn shows that it was a labor-intensive process requiring hard physical activity that kept them physically fit and lean: “In preparing their corn for food,” the Mande used a “large wooden mortar called a paloon, in which they bruise the seed until it parts with the outer covering, or husk, which is then separated from the clean corn by exposing it to the wind; nearly in the same manner as wheat is cleared from the chaff in England.”41 The woman then took the freed corn, put it in a mortar, and beat it into meal. This process was used to make a variety of corn-based dishes in different countries. For example, Mande along the Gambia River made a type of cornmeal-based pudding using milk and water; it was called nealing and may originally have been made with millet. Park tells us that, during lean times, the Mande also ate for breakfast “a pleasant gruel called fondi” made from foraged berries and millet or couscous. Both nealing and fondi seem like precursors of the rice puddings and custards made so popular by enslaved cooks on Carolina rice plantations.42

In the book Roots, Alex Haley traced his family history back to the 1750s Mande village of Juffure. During lean times, villagers in Juffure survived on edible leaves, insects, rodents, and roots. The Mande developed distinctive dishes through cooking alternative sources of protein such as beetles and grasshoppers. “These would have only been tasty tidbits at another time of year, but now, on the eve of the big rains, with the hungry season already beginning, the toasted insects had to serve as a noon meal, for only a few handfuls of couscous and rice remained in most families’ storehouses.” After the rains and harvest came, the Mande diet changed drastically. The people then feasted on meat three times a day until they completed the harvest. The ability to locate food during lean times in West Africa proved very profitable to enslaved Africans in the Americas, where planters distributed niggardly rations that kept most slaves famished, forcing them to hunt and steal food in order to survive.43

One-pot meals were the most common among both the Igbo and the Mande. For example, the British slave trader Theodore Canot tasted an unforgettable mutton stew called bonne-bouche in the Mande town of Kya. Canot recalled: “The savory steam of a rich stew with a creamy sauce saluted my nostrils, and, without asking leave, I plunged my spoon into a dish that stood before my entertainers, and seemed prepared exclusively for themselves. In a moment I was invited to partake of the bonne-bouche; and so delicious did I find it, that, even at this distance of time, my mouth waters when I remember the forced meat balls of mutton, minced with roasted ground nuts, that I devoured that night in the Mandingo town of Kya.”44

Mande women taught their daughters how to broil, roast, bake, and fry meats—a talent they would liberally exercise in slave quarters and big-house kitchens in the Americas. In Africa, Mande culinary arts called for jerking meat (salting and drying it in the sun) to conserve it. Among Mande living in the interior of the Gambia River region, salt was “the greatest of all luxuries,” because their mostly vegetable diet “creates so painful a longing for salt, that no words can sufficiently describe it,” says Park.45 Perhaps this is the origin of the African-American love affair with salty foods that has resulted in a disproportionately high diagnosis of hypertension in contemporary communities of African descent in the United States.

Coastal dwellers among the Mande would smoke, fry, salt, dry, boil, or pickle fish or serve catches raw, much like their descendants forced to migrate to the West Indies and the Carolinas. The fish they caught in West Africa, writes Park, “are prepared for sale in different ways. The most common is by pounding them entire as they come from the stream in a wooden mortar, and exposing them to dry in the sun. . . . It may be supposed that the smell is not very agreeable; but in the Moorish countries to the north of the Senegal [River], where fish is scarcely known, this preparation is esteemed as a luxury, and sold to considerable advantage.”46 Mande women would purchase the dried fish at market and then add pieces of it to boiling water, vegetables, seasoning, and couscous to make a fish gumbo. The knowledge and practice of Mande gumbo making continued in the Americas with regional differences, especially in port cities such as Charleston, Savannah, Mobile, and New Orleans.

Like the Igbo, Mande people skillfully used vegetable oils like shea butter and palm oil to deep-fry and flavor poultry. Mande descendants continued the cooking technique in the Americas, only in the colonial South lard replaced the healthier palm oil and shea butter. Fried or curried chicken and greens were yet another culinary tradition passed on to African Americans and West Indians by their Mande forebears. West African women batter dipped and fried chicken, grilled it, and cooked it in a curry sauce. They commonly served chicken with collard greens and dumplings. African Americans also learned from their Mande ancestors the practice of using chicken innards (hearts, lungs, kidneys, and gizzards) in their soups and stews as flavor enhancers.47 The African-American practice of eating chicken on special occasions is also a West Africanism that survived the slave trade. Among the Igbo, Hausa, and Mande, poultry was eaten on special occasions as part of religious ceremonies.48

SPECIAL OCCASIONS: FOOD AND AFRICAN RELIGION

Before Africans arrived in colonial America, they had a well-developed religious life that included “iconic foods served in ritualistic ways.”49 There are several keys to understanding the religious rituals that survived the African slave trade and would shape the African-American concept of soul: spirituality, love, patience, hard work, and pride. These were essential components of what would later become soul food. First, West African religions honored and acknowledged God and the community’s relationship to the spiritual world in everyday activities and on special occasions. Second, Africans held a belief that an honorable person showed reverence to God, community leaders, friends, and family through the use of music and food. As a result, West African ancestors incorporated music and food into their religious rituals and celebrations. Examples from different parts of West Africa and during different centuries illustrate this.

In general, we know that, on special occasions, hens were an important ingredient in many dishes. “The person who is to be made a Nobleman,” writes Dutchman Pieter de Marees, “makes everything ready, such as food and drink in order to regale his guests well and give them a proper treat. He buys Chickens and many pots of Palm Wine, and sends to each Nobleman’s home a Fowl together with a Pot of Palm Wine, so as to make them happy with him.”50 Africans sought to make their deceased ancestors happy with offerings of food as well.

The East Nigerian–born Olaudah Equiano (1745–1801) tells us that, in traditional Igbo religions and cultures, people had the practice of making “oblations of the blood of beasts or fowls” at the graves of dear friends and relations, whom they believed would “attend to them, and guard them from” evil.51 An English naval officer and explorer, William Allen, observed that just before the planting of yams, villagers along the Niger River contributed an abundance of palm wine and game to a yearly yam-planting festival, while the inhabitants of the city of Accra, in the kingdom of Ghana, commonly hunted and prepared hare.52

Considered the most important religious event of the year in the Niger River region, the planting festival involved a multitude of villagers, who devoted a portion of their food and drink to their god as libations before the start of a communitywide planting season feast. A similar celebration occurred at the completion of the planting season. The “Marocho, which occurs about our Christmas period of the year,” writes Allen, “is the greatest religious festival.” The weeklong feast featured goat and poultry dishes as well as a steady succession of “dancing, singing, and firing of muskets.”53 According to de Marees, Africans in Guinea served chickens as a funeral repast. Women did all the preparations. “For having a good time together at the funeral: they cook a Sheep, as well as Fowls and other food which they usually eat.”54 There is no record of what Africans ate after they learned about the capture and exportation of a loved one, but we do know what slavers forced their captives to eat before and during the Middle Passage.

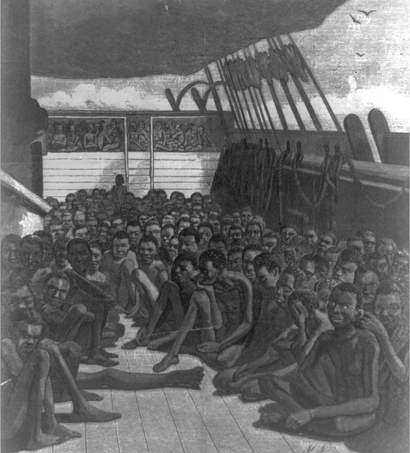

FIGURE 1.2 “The Slave Deck of the Bark ‘Wildfire,’ Brought into Key West on April 30, 1860.” Harper’s Weekly, June 2, 1860, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-41678.

SLAVE PROVISIONS

As an eighteenth-century travel account explains, slave traders forced African captives to eat foods with both Old and New World ingredients onboard slave ships destined for the Americas. The enslaved Africans described in the following scene were native to the coast of Guinea: “The diet of the Negroes on board is a sort of pulp, composed of rice and horse-beans, with yams, boiled and thickened to a proper consistency, which is called a Dab-a-Dab, sometimes with meat in it, to this there is added a sauce, called flabber-sauce by the sailors, made of palm oil, mixed with flour and pepper; and there is an overseer with a cat of nine tails to force those to eat who are sullen and might refuse; an attempt to starve themselves being considered as the greatest possible crime, and receiving the severest punishment. This food is accounted more salutary, and nearer to their accustomed way of feeding than salt flesh.”55

West African eating customs played an important role in the formation of African-American eating habits in what would become the southern United States. The consumption of yams prepared in various ways is distinctly African. The Igbo used foofoo to eat stews with their hands in a manner similar to the way we use utensils. African Americans in South Carolina would later use corn bread in a parallel way to sop (or soak up) a mixture of molasses and the grease produced by frying salt pork and to eat collard greens. Another parallel is how African women used shea butter and palm oil to season and cook most of their vegetables, legumes, chicken, and fish. African Americans in the South would later use fatback and salt pork in the same way to prepare vegetables and beans. The continuation of African culinary practices among African Americans can also be seen in the use of large amounts of salt and pepper to season food. These are Africanisms that stand apart from the influence of the Portuguese on African cuisine, which began in the sixteenth century.

Before the Africans’ enslavement and forced migration to the Americas, the Portuguese introduced maize to the diet of Africans and increased the region’s population of hogs and hens for consumption. By the 1600s, Africans had developed the habit of eating corn in various ways, including in puddings, breads, and porridges reminiscent of grits. In some instances, corn complemented or replaced African grains like millet. Groups like the Igbo, however, continued to eat primarily rice. Their knowledge of rice cultivation motivated rice planters in lowland South Carolina to seek them out by name when purchasing slaves. Africans brought their way of cooking long grain rice with them to South Carolina; in the kitchen, it was the African cook and her culture that made the greatest thumbprint on South Carolina recipes, not the European culture of the mistress.56

Among West Africans like the Mande people, meat consumption was seasonal. During harvesttime, meat was eaten three times a day. After the harvest, women used meat sparingly as seasoning in stews and sauces rather than as the main course. This practice continued among Africans shipped to the Americas. During dry seasons and famines in West Africa, insects like the locust replaced the large and small game that vanished during long droughts. As for chicken, it was generally served to guests and used as part of religious observances; this is another example of an Africanism that continued in the South.

In the Americas, Africans would continue some traditions, like eating roasted yams, while altering or creating substitutes for other traditions. Amerindians and Europeans influenced the food that the earliest Africans used to complement and substitute for their eating traditions before arriving in the Americas. Captivity and chattel slavery exposed the Igbo and Mande to various new eating habits and food preparation methods, but they largely had access to most of the ingredients familiar to them in Africa. And before they were forcibly sent to the Americas, African women had already begun cooking with imported crops, many of them from the Americas, such as corn, cassava, and pumpkins.