8 Lacan and philosophy

No writer in the history of psychoanalysis has done more to bring Freudian theory into dialogue with the philosophical tradition than Jacques Lacan. His work engages with a dauntingly wide array of thinkers, including not only his near contemporaries (Saussure, Benvéniste, Jakobson, Bataille, Merleau-Ponty, Lévi-Strauss, Piaget, Sartre, Kojève, Hyppolite, Koyré, and Althusser), but also other figures reaching back to the Enlightenment (Nietzsche, Kierkegaard, Marx, Hegel, and Kant) and beyond, from Spinoza, Leibniz, and Descartes, to Pascal, Saint Augustine, Aristotle, Plato, and the pre-Socratics.1 His references, moreover, are not limited to the familiar landmarks of the post-Structuralist tradition who have so often been used to interpret him (Kojève and Hegel, Saussure and Lévi-Strauss), but include numerous figures from the British tradition (Bertrand Russell, Jeremy Bentham, Isaac Newton, Jonathan Swift, and George Berkeley), as well as from the history of science and mathematics (Cantor, Frege, Poincaré, Bourbaki, Moebius, Huyghens, Copernicus, Kepler, and Euclid). While some of these references are no doubt merely grace notes, introduced to embellish a notoriously labyrinthine and Gongoristic style, it is impossible to ignore the fact that his engagement with a large number of these figures is serious, focused, and sustained over many years.

The task of commentary is therefore enormous. Lacan’s early seminars (1953–5) are marked by a prolonged encounter with Hegel, who had a substantial and abiding effect not only on his account of the imaginary and the relation to the other (jealousy and love, intersubjective rivalry and narcissism), but also on his understanding of negation and desire while leading to the logic of the signifier.2 His Seminar on The Ethics of Psychoanalysis, well-known for its extended reading of Sophocles’ Antigone, also contains a treatment of Kantian ethics, Bentham’s utilitarianism, and Aristotle’s philosophy, including not only the Nicomachean Ethics, but also the Poetics and the Rhetoric, and especially their discussions of “catharsis” – a term which has an elaborate history both in esthetic theory and in psychoanalysis itself, where the “cathartic method” played an important role.3 Here already, an enormous task is proposed, concerning the relations between art and psychoanalysis, as well as the transformation that separates modernity (Kant’s esthetic theory) from the ancient world (Aristotle’s Poetics) – a historical question that is repeatedly marked by Lacan, as if to suggest that psychoanalytic theory, in order to be truly responsible for its concepts, must account for its own historical emergence as it seeks to articulate its place in relation to the philosophical tradition which it inevitably inherits.

Every text is full of such challenges. His Seminar on Transference provides a sustained reading of Plato’s Symposium, and his Seminar on The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis contains a well-known commentary on Merleau-Ponty’s discussion of painting, which appeared in the philosopher’s posthumously published book, The Visible and the Invisible, a work which had a significant impact on Lacan’s concept of the gaze.4 Each of these encounters, taken by itself, calls for a careful analysis, and there are many others, including influences that were not the subject of explicit commentary, beginning with his attendance at Kojève’s lectures.5

Lacan spoke frequently of Heidegger, starting in 1935, in Recherches philosophiques and Evolution psychiatrique, where we find early book reviews of Henri Ey and Eugène Minkowski.6 References to Heidegger continue in “Propos sur la causalité psychique,” in Seminar II, in “Le Mythe individuel du névrosé,” in the discussion of Heidegger’s “Das Ding” in Seminar VI, in “L’Instance de la lettre,” and elsewhere, including texts that are less well known to Anglo-American readers, such as “Allocutions sur les psychoses de l’enfant,” and the “Rome discourse.”7 It would be a mistake, moreover, to suppose that all these references merely repeat the same idea or formula, for in one case he is concerned with the temporality of the subject and the text of Being and Time, while in another he is concerned with the distinction between the “thing” and the “object,” and the text of Poetry, Language, Thought.8 A cursory mention of “the famous being-towards-death” will simply not do justice to these complex relationships. Lacan’s interest was sufficiently piqued that he translated Heidegger’s essay “Logos” for the first issue of La Psychanalyse; and the most frequently cited of these references, taken from the final pages of the “Function and field of speech and language in psychoanalysis,” reads almost like a manifesto: “Of all the undertakings that have been proposed in this century, that of psychoanalysis is perhaps the loftiest, because the undertaking of the psychoanalyst acts in our time as a mediator between the man of care and the subject of absolute knowledge” (E/S, p. 105). Such a proposal, placing Freud in relation to both Heidegger’s account of Dasein (the “man of care”) and Hegel’s phenomenology (“the subject of absolute knowledge”), could occupy more than one doctoral thesis, as could any number of these engagements with the philosophical tradition.9

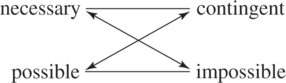

Canonical figures in continental philosophy, moreover, are not the only important names for Lacan. Readers who are accustomed to a reception governed by Hegel and Saussure may be surprised to know that Aristotle is one of the most frequent points of reference in the entire Lacanian oeuvre. In Seminar XX: Encore, for example – as we shall see more clearly in a moment – Aristotle provides a guiding thread for an argument that passes from Freud’s account of masculinity and femininity, through symbolic logic (the famous quantifiers of sexual difference), and thence to the modal categories of existence (possibility, impossibility, contingency, and necessity) found in Aristotle but reconfigured through the semiotics of Greimas – all this being punctuated by references to angels (discussed thereafter by Irigaray), the concept of the “soul,” and the Nicomachean Ethics, which is particularly interesting to Lacan for Aristotle’s remarks on “courage” and “friendship.” A heady mix, to be sure, but we shall see that these references are not simply thrown together in a careless manner.

In the face of these many references, we can hardly do more than sketch a few aspects of this vast territory. Even if we bracket the figures in anthropology, linguistics, and mathematics (though they have an unmistakable claim to philosophical significance), drawing a very narrow limit around the title of “philosophy,” each of these relationships, taken by itself, would merit an extended commentary.10 In addition to these many names, moreover, there are numerous concepts that Lacan develops as an explicit challenge to the philosophical tradition – from “doubt” and “certainty,” or “belief” and “truth,” to “representation” and “reality” – each of which has a basis in Freud (one has only to recall “The Loss of Reality in Neurosis and Psychosis,” SE 19, pp. 181–7, or the important discussion of “doubt,” “affirmation,” and the “judgment of existence” in Freud’s remarkable article on “Negation,” SE 19, pp. 233–9).11 (When I “believe” in the existence of the maternal phallus, even as I “know” that it does not “exist” in “reality,” what exactly are the stakes of these terms, and how might the psychoanalytic elaboration of these terms challenge the philosophical use of this same vocabulary?) And there are countless propositions that Lacan puts forth which have a claim to philosophical significance. These pronouncements have often been used to encapsulate Lacan’s general position, but they are not as simple as they appear. Consider his remark that “there is no such thing as pre-discursive reality.” While such formulae have often been used to construe Lacan as a theorist of “discursive construction,” here too a meticulous treatment is required, for one can hardly conclude from this remark that “everything is symbolic” for Lacan (given that the Real and Imaginary are irreducible to discourse), any more than one can suppose that Lacan’s reasons for putting forth this proposition automatically coincide with the arguments of others (historicists, Structuralists, pragmatists, etc.) who might make the very same statement.12

In addition to all this, moreover, there are extended discussions of figures who have received far less attention in the Anglo-American literature on Lacan, due in part to the fact that many texts have yet to appear in English, or even in French. His discussion of Marx, for example – especially in La Logique du fantasme and D’un autre à l’autre, in both of which he discusses the notion of “surplus value” – remains unpublished. And in the case of Descartes, one would have to account not only for the well-known comments in The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis and “The agency of the letter” (comments taken up almost verbatim by Foucault in The Order of Things 13), but also for Lacan’s remarks in “Propos sur la causalité psychique” (1946), “La Science et la vérité” (1965); and two unpublished seminars, Seminar XII: Problèmes cruciaux (1964–5), and Seminar XIV: La Logique du fantasme (1966–7), where one finds an extended variation on the formula “cogito ergo sum.”14

Nor can one dismiss these many excursions into philosophy as a digression from “properly psychoanalytic” concerns, as though readers with a clinical interest could somehow avoid them, for it is clear that Lacan turns to the philosophical tradition, not for philosophical reasons, but in order to clarify matters that lie at the very heart of Freudian theory.15 In the case of Descartes, for example, the relation between “thinking” (the cogito) and “being” (sum) is explored, not for epistemological reasons, or in order to establish the truth of any beliefs (“What can I know with certainty? What object escapes the corrosive movement of doubt?”), but for the light it casts on the problem Freud raised by speaking of “representation” (Vorstellung), and more precisely the limits of representation. For, as Freud famously said, there is something of the unconscious that remains unavailable to interpretation. Recall the well-known formulation in The Interpretation of Dreams: “There is often a passage in even the most thoroughly interpreted dream which has to be left obscure; this is because we become aware during the work of interpretation that at that point there is a tangle of dream-thoughts which cannot be unravelled and which moreover adds nothing to our knowledge of the content of the dream. This is the dream’s navel, the spot where it reaches down into the unknown” (SE 5, p. 525, emphasis added). This “nodal point” in the unconscious remains inaccessible not because interpretation has been deficient, but in principle and by its very nature, which means not only that it has to be left obscure, but also that it cannot be construed as an object of knowledge: like the navel of the dream, something of the unconscious thus falls outside the field of representation.

Lacan likewise remarks on the limits of representation, and this is what guides his remarks on the disjunction between “thinking” (the ego in ego cogito) and “being” (the register of the subject). As is often the case with Lacan, one has to be particularly careful not to impose a familiar Lacanian dogma on these philosophical references. For the distinction between the “I” of ego cogito and the “I” of ego sum is not the usual Lacanian distinction between the Imaginary and the Symbolic, whereby the “ego” that speaks at the level of consciousness is distinguished from the “subject” of the unconscious, which speaks through the symbolic material that intrudes upon the discourse of the ego. Lacan indeed stresses this distinction, not only in the often quoted “schema L” but in formulae such as the following: “the unconscious of the subject is the discourse of the Other” (E/S, p. 172), or “the unconscious is that part of the concrete discourse, insofar as it is transindividual, that is not at the disposal of the subject in re-establishing the continuity of his conscious discourse” (E/S, p. 49). But when it comes to this Cartesian meditation of his, played out as a disjunction between thinking and being, we are faced with a very different issue. And here again, we have a limit to the supposedly “linguistic” account of the unconscious in Lacan’s thought. For while signifiers certainly play a formative role in organizing the life of the subject (mapping out various symbolic identifications, as “obedient,” “unconventional,” “masculine,” etc.), functioning differently at the level of conscious and unconscious thought, they will never entirely capture the “being” of the subject, according to Lacan. This disjunction is what the notorious Lacanian “alienation” actually means – not simply the imaginary alienation in which the ego is formed through identification with an alter ego in the mirror stage (a thesis used to link Lacan to Kojève and Hegelian rivalry), nor even the symbolic alienation in which the subject is forced to accept the mediating role of language and its network of representations (a thesis used to link Lacan to Saussure, Lévi-Strauss, and Althusserian “interpellation”), but rather that alienation in which the subject, by virtue of entering the symbolic order, finds itself lacking, deprived of a measure of its “being” – a thesis which complicates the supposedly symbolic account of the subject, and also has effects on our understanding of the unconscious.

Thus, following Descartes, we are led to the conclusion that, while it may be correct to say the unconscious can be followed through various symbolic manifestations (the lapsus, the dream, free association, negation), there is also an aspect of the unconscious which belongs to the order of the real, understood as a dimension irreducible to representation. The “subject” of the unconscious in Lacan is therefore something other than a symbolic phenomenon, and constantly disappears with the “closing” of the unconscious. “The signifier,” Lacan says, “makes manifest the subject . . . But it functions as a signifier only to reduce the subject in question to being no more than a signifier . . . There, strictly speaking, is the temporal pulsation . . . the departure of the unconscious as such – the closing,” which Ernest Jones caught sight of when he spoke of the disappearance or “aphanisis” of the subject. Thus, we may indeed follow the position of the subject at the level of the signifier, where unconscious “thought” is revealed, but “aphanisis is to be situated in a more radical way at the level at which the subject manifests himself in this movement of disappearance that I have described as lethal” (S XI, pp. 207–8).16 This means – contrary to Descartes – that thinking and being will never coincide, and that we are faced with a constitutive rupture between the symbolic and the real.17 It also means – contrary to what many readers of Lacan may suppose – that the famous symbolic order will never be sufficient to grasp the “subject” of psychoanalysis, because the being of the subject is irreducible to any symbolic or imaginary representation. In short, Lacan’s account of the Freudian theory of “representation” puts a limit to the famous “linguistic” interpretation of psychoanalysis that Lacan is so often said to have promulgated, and Descartes is the avenue through which this point is made.

This thesis is certainly of interest to the philosopher, and to anyone interested in the status of the “subject” in contemporary thought, but we must also attend to the clinical aspects of the argument. For as a result of this claim, analytic practice will require a technique that is able to follow not only the symbolic trail of the unconscious, but also its movement of disappearance or fading – as Freud suggested in his remarks on the death instinct, which concerned a movement of annihilation to which the subject as such is prone. Without developing the technical consequences of this step, we can nevertheless indicate its importance, in terms of the distinction between the symbolic dimension of the unconscious and the transference. For in fact, as Russell Grigg has shown, it is precisely this opening and closing of the unconscious that led Freud to discover the transference in the strict sense, as an aspect of the unconscious that is conceptually quite distinct from whatever is revealed through the signifying chain of the dream and free association.18 As Freud himself remarked, there is often a point in the discourse of the analysand where the chain of associations runs dry. “Perhaps you are thinking of me?” he suggests, as if this impasse in discourse somehow appeared in conjunction with the presence of the analyst. Freud thereby marks a clear division between the signifier (the labor of free association and dream elaboration), and a new domain of the transference, wherein a certain lethal dimension of the subject is revealed. Lacan formulates this clearly in Seminar XI, in a chapter called “The transference and the drive”: “What Freud shows us, from the outset, is that the transference is essentially resistant, Übertragungswiderstand. The transference is the means by which the communication of the unconscious is interrupted, by which the unconscious closes up again” (S XI, p. 130). This movement of disappearance or “closing,” in which the “being” of the subject is excluded from the chain of signifiers, also leads Lacan to elaborate a distinction between the signifier and jouissance, understood as a dimension of lethal enjoyment in which the desire of the subject is compromised. Even without developing these points, we can already see that Lacan’s ultimate concern is not with the texts of philosophy, and that his protracted engagement with Descartes has a bearing on Freudian theory. This is finally why Lacan argues that the “being” of the subject as such is irreducible to the symbolic order (the unconscious “I think”).

This brings us to the central problem facing anyone who wishes to address the question of “Lacan and philosophy.” On the one hand, Lacan’s references to the philosophical tradition are intended to be serious, and require a rigorous and properly philosophical exposition – he cites particular texts, puzzles over problems of translation, and clearly expects his audience to follow individual passages; on the other hand, his reasons for turning to the philosophical tradition are not, finally, philosophical, but derive from the field of psychoanalysis itself, understood as a domain that, whatever it may stand to learn from philosophy, has its own theoretical specificity, and develops in relation to a clinical field that is simply not present in the philosophical arena. Any attempt to clarify Lacan’s use of philosophical texts must attend to this double trajectory.

Our survey of names, however daunting in itself, thus only hints at the depth of the problem, for with every philosophical reference, Lacan is simultaneously concerned with matters that lie within psychoanalytic discourse itself. This means that the serious reader will be obliged not only to develop the philosophical background of the references Lacan makes (for it must be acknowledged that Lacan himself never provides a properly philosophical exposition of the concepts and texts on which he depends), but also to isolate the clinical issues that are at stake whenever Lacan engages with the philosophical tradition (identification, the object-relation, transference, the drive, and other concepts that are particular to psychoanalysis). A simple gesture towards “philosophy” or “Hegelian alienation” or “structural linguistics” will therefore do nothing to clarify his many allusions. In each case, the clinical stakes of his remarks must be isolated and defined, if we are to see how Lacan makes use of the philosophical tradition. And in each case, we must mark the disjunctions that arise whenever the interests of philosophy run up against the exigencies of the clinical domain.

Lacan’s treatment of negation is an excellent case in point. For his remarkable analysis of the three types of negation in Freud’s vocabulary, while it certainly relies on philosophical resources for its development, and leads him to a long immersion in Hegel’s “dialectical” or “productive” negation, nevertheless has a diagnostic purpose that is entirely absent from Hegel’s own work. For Lacan, Verneinung, Verleugnung, and Verwerfung (respectively “denial,” “disavowal,” and “foreclosure”) in Freud’s terminology designate three distinct forms of negation, not merely in a logical sense, but in the sense that they correspond to three distinct psychic mechanisms that can be correlated with the diagnostic categories of neurosis, perversion, and psychosis. Where “denial” indicates the neurotic repudiation of a thought which the unconscious is in the process of expressing (“You will say it’s my mother in the dream, but I assure you it’s not my mother,” SE 19, p. 235), “disavowal” by contrast indicates a more profound refusal, which does not so much acknowledge the truth under the sign of negation (“it’s not my mother”), but rather repudiates altogether what is negated. The standard clinical case of disavowal concerns castration, and more precisely maternal castration, and the subjective consequences include a perceptual aspect (an imaginary distortion of sexual difference, notably in fetishism) that is distinct from the symbolic mechanism of neurotic denial. Freud expressly underscores this point in “Fetishism” (SE 21, pp. 149–57). Noting, first of all, that the term “repression” can explain this phenomenon, in which an observation (the lack of a penis) has been registered and is nevertheless simultaneously refused, he specifies further. For in the case of denial – “it’s not my mother” – are we not also dealing with a repression, which bears on an unconscious idea? To be precise, then, Freud observes that the affect associated with the perception of woman’s lack of a penis is repressed, while the idea, by contrast, is “disavowed”: “If we wanted to differentiate more sharply between the vicissitude of the idea as distinct from the affect, and reserve the word Verdrängung [‘repression’] for the affect, then the correct German word for the vicissitude of the idea would be Verleugnung [‘disavowal’]” (p. 153). The affect – anxiety, for example (as in “castration anxiety”) – is then no longer experienced as such, having been repressed, while the idea remains present under the form of disavowal. This “remaining present” suggests why Freud writes that, in the face of woman’s castration, the fetishist “retains this belief [in the presence of the phallus] but also gives it up.” One might think this formulation functions precisely as repression does, since we have a “no” and a “yes” simultaneously, such that the belief is both maintained and renounced (“it is/is not my mother”). But Freud insists that, in fetishism, “repression” characterizes what happens to the affect, whereas “disavowal” is what happens to the idea or “belief” – what Lacan would call the symbolic representation, the order of the signifier. What then distinguishes “disavowal” from repression, and why does Freud say that “repression” in this case only bears on the affect? Does not repression normally bear also on ideas, as when a repressed thought emerges under the sign of negation (“it’s not my mother”)?

The solution is that, in the case of “disavowal,” the mode of rejection is stronger than in repression. What is disavowed is not “repressed” (and thus able to return), but is rather more profoundly refused; and in order to clarify this difference, Freud relies on the perceptual dimension. The “idea” (or signifier) of castration is indeed “retained” and “given up,” but unlike repression, where the idea is normally retained only in the unconscious, in disavowal the affect is repressed, while the idea of maternal castration is not repressed, but remains present alongside its negation. This is why the fetishist requires another mechanism by which the negation of this idea can be maintained – not a mechanism of repression, by which the symbolic representation (the idea or signifier) would be lodged in the unconscious, but a mechanism of disavowal, by which the imaginary representation (the visual image) remains present in the field of perception, by means of the fetish. Accordingly, Freud immediately points out that Laforgue is wrong to suggest that in fetishism the perception is simply eliminated, “so that the result is the same as when a visual impression falls on the blind spot on the retina” (SE 21, p. 153). On the contrary: in disavowal, the mode of negation is different from mere absence or blindness, and Freud therefore says that in fetishism, “we see that the perception has persisted, and that a very energetic action has been exerted to keep up the denial of it” (ibid.). We thus see more clearly why Freud claims that the affect is “repressed” while the idea is “denied”: if the subject denies the idea (the concept or signifier), and yet simultaneously retains it as a conscious belief, that retention takes place in the Imaginary, through the perceptual presence of the fetish. The logic of negation in Freud’s work thus requires an account that will be sensitive to the mechanisms of psychic life, at the level of the symbolic, the imaginary, and the real. As for the final term, “foreclosure” by contrast indicates, for Lacan, a still more profound absence of lack, such that the subject has not even registered the difference, the symbolic differentiation, that the fetishist seeks to conceal. “Foreclosure” thus designates a mode of negation that is closer to psychosis than the other mechanisms, which remain inscribed within the system of representation more securely. Thus, even without elaborating these distinctions in any detail, we can already see that it is not enough to point to Lacan’s supposed reliance on Hegel, or any other logic of negation, without also exploring the clinical dimension of Lacan’s formulations.

This conceptual movement, whereby a meticulous attention to philosophical distinctions is sustained, but mobilized in the interest of the clinical domain, is evident throughout Lacan’s work. In Seminar VII, for example, Lacan turns from Kant’s ethics, which has been a central focus in his argument, and takes up The Critique of Judgement, citing particular passages and insisting that his audience look closely at the text: “I intend to have you go over the passages of Kant’s Critique of Judgment that are concerned with the nature of beauty; they are extraordinarily precise” (S VII, p. 261). Two chapters later, he is still reading the text, focusing in particular on one of the most obscure passages in Kant’s account, namely section 17, entitled “Ideal beauty” – a passage in which Kant argues somewhat strangely that an ideal of beauty cannot properly be considered as belonging to the experience of the beautiful. An “ideal” of beauty is not rejected by Kant because it has an abstract, cognitive component (for an “ideal” is not an “idea”). Nevertheless, the ideal introduces a standard that thwarts the free play of the imagination, and thus it cannot be considered to yield a pure judgment of taste. Without quoting, Lacan repeats Kant almost verbatim: “The beautiful has nothing to do with what is called ideal beauty” (S VII, p. 297). This brings us to the crucial point, for what Kant tells us in section 17 is that there is only one ideal of beauty, and that is the form of the human body. “Only man,” Kant says, “among all objects in the world, admits, therefore, of an ideal of beauty, just as humanity in his person, as intelligence, alone admits of the ideal of perfection.”19 The human image is therefore not one image among others, but has a special character that disrupts the category of the beautiful in Kant’s analysis, by bringing into play a dimension of infinity, a rupture with visibility, an “ideality” that in fact only genuinely finds its place in the second book of Kant’s text, the analytic of the sublime (this is why Kant excludes the “ideal of beauty” from the category of the beautiful – a point Lacan does not follow, preferring to alter the conception of the beautiful as such, so that it will account for this rupture with the visible). This is the crucial point for Lacan: “Even in Kant’s time,” he says, “it is the form of the human body that is presented to us as the limit of the possibilities of the beautiful, as ideal Erscheinen. It once was, though it no longer is, a divine form. It is the cloak of all possible fantasms of human desire” (S VII, p. 298). Thus, even without following the details of this analysis with the care that they deserve, we can see that Lacan’s reference to “Kant’s theory of the beautiful” is hardly a passing fancy, thrown out to buttress his intellectual credentials, but a genuine and meticulous encounter with the philosophical tradition.

And more important still, for our present argument – and this is why a little detail has been necessary – is the fact that Lacan does not simply impose his well-worn doctrines about “the imaginary body” onto the philosophical text, but on the contrary, seems to be transforming his own conceptual apparatus under the influence of the philosophers he reads. For he claims here that the image of the human form, unlike other instances of the beautiful that may be apprehended in the perceptual image, has a sublime element to it, a rupture with visibility, an aspect that touches on the infinite and the “unpresentable,” as Kant says, which means that it can no longer be understood in terms of the thesis on the imaginary body so dear to the early Lacan, in which the human form would be captured by the unified totality that is given through the Gestalt. The impasse that Kant’s own analysis of the beautiful confronts when it reaches the human image (“the limit of the possibilities of the beautiful”) thus provides a path for Lacan’s own conceptual development, even if, as we have already stressed, that path swerves off in the direction of psychoanalysis, towards an account of the “fantasms of human desire.”

Virtually every text presents us with difficulties of this order, which demand an enormous erudition on the part of the readers, and a careful attention to the details of the texts Lacan takes up, even if (it cannot be said enough) Lacan’s own reasons for pursuing these details will lead him in another direction, not towards a philosophical discourse, but towards problems internal to psychoanalysis – as in the present case, where the stakes of his analysis are clearly focused, finally, on the question of the gaze, the human body, and the concept of “fantasy.” This is indeed the fundamental challenge posed by the conjunction of “psychoanalysis and philosophy.” And Lacan’s major contribution to the analytic community was to push this confrontation to its limit, in order that it might yield genuine results. For psychoanalysis is clearly a discipline in its own right, with a technical vocabulary and a field of investigation that distinguish it from the domain of philosophy; and yet, at the same time, psychoanalysis itself cannot possibly flourish if it refuses to develop its concepts in a rigorous manner, shrouding itself in the private “enigma” of the clinical experience, or borrowing an inappropriate luster from its proximity to a “medical” or “scientific” model that obscures the specificity of the analytic process, and avoids the question of the “subject” in favor of vaguely psychological notions that distort the very arena in which psychoanalysis operates. “Concepts are being deadened by routine use,” Lacan used to say, and analysts have taken refuge from the task of thinking: this has led to a “dispiriting formalism that discourages initiative by penalizing risk, and turns the reign of the opinion of the learned into a principle of docile prudence in which the authenticity of research is blunted before it finally dries up” (E/S, pp. 31–2). Such is the paradox that leads Lacan to this chiasmus of engagement with philosophy and other conceptual fields: it is only through contact with these other domains that psychoanalysis can find its own way in a more rigorous fashion.

When Lacan draws on philosophical texts, it is never simply to subject psychoanalysis to concepts extracted from another field; on the contrary, the very terms that he borrows from other domains are themselves invariably altered when they enter the clinical arena. If this is indeed the case, however, it should be possible to show precisely how considerations internal to psychoanalysis will affect whatever concepts Lacan may draw from the philosophical tradition. And in fact, Lacan is careful to mark these transformations as he proceeds. Thus, for example, his analysis of Descartes – from the method of radical doubt by which Descartes suspends the pieties of the tradition, interrogating any knowledge he has inherited from his ancestors, and bringing into question every certainty of the subject (in a procedure that is not without interest for the psychoanalyst), right down to the details of the “third party” who stands as a guarantee for the “I am” in the “Third meditation,” when doubt threatens to swallow up every assertion – all this nevertheless leads Lacan to “oppose any philosophy directly issuing from the Cogito” (E/S, p. 1), not because he wishes to elaborate a philosophical position, but precisely because of the clinical orientation that makes Lacan’s relation to the question of the “cogito” something other than a philosophical relation. Lacan says that the Freudian cogito is “desidero,” and when the process of doubt reaches its end in analysis, it is not because an epistemological foundation has been reached, but because a “moment to conclude” has been fashioned for the subject.

The same point arises with respect to his notorious Hegelian influences. Hegel certainly had a powerful impact on Lacan’s conceptual formation, but Lacan does not fail to mark out his difference from Hegel, which derives from a perspective that is clinically informed. Consider the relation between “truth” and “knowledge”: just as, for dialectical thought, the movement of truth will always exceed and disrupt whatever has been established as conscious knowledge, such that knowledge will be exposed to a process of perpetual dislocation and productive negativity, so also for Freud, the consciousness of the ego remains in a state of permanent instability, perpetually disrupted by the alien truth of the subject that emerges at the level of the unconscious (the “discourse of the Other”). According to Lacan, Hegel saw clearly this discrepancy between “knowledge” and “truth,” and gave it both a logical coherence and a temporal significance from which psychoanalysts could certainly profit. Indeed, this Hegelian framework went far towards establishing the crucial distinction between the “ego” and the “subject,” and led Lacan to argue that the analyst should always stand on the side of truth, which implied a rigorous suspicion with respect to “knowledge” (“truth,” Lacan says, “is nothing other than that which knowledge can apprehend as knowledge only by setting its ignorance to work”). In this sense, “Hegel’s phenomenology . . . represents an ideal solution . . . a permanent revisionism, in which truth is in a state of constant reabsorption in its own disturbing element.” This movement of reabsorption, however, is typical of the philosophical arena, devoted as it is to a conceptual exhaustion of the phenomena it discovers (“an ideal solution”). In this sense, for Hegel, according to Lacan, the disruptive power of the real finds a perpetual synthesis with the symbolic elaboration of knowledge: as Lacan says in “Subversion of the subject,” “dialectic is convergent and attains the conjuncture defined as absolute knowledge,” and as such “it can only be the conjunction of the symbolic and the real” (E/S, p. 296). But where Hegel regarded “truth” and “knowledge” as dialectically intertwined, such that the disruptive power of truth could eventually be formulated conceptually, and thus put in the service of knowledge (“reabsorbed” by the discourse of philosophy, such that negation is always “productive,” always symbolically elaborated), Freud leads us in a very different direction, according to Lacan, insofar as repression – and above all sexuality – put truth and knowledge in a “skewed” relation that cannot be dialectically contained: “Who cannot see the distance that separates the unhappy consciousness . . . from the ‘discontents of civilization’ . . . the ‘skew’ relation that separates the subject from sexuality?” (E/S, p. 297).20 For Lacan, then, “Freud reopens the junction between truth and knowledge to the mobility out of which revolutions come” (E/S, p. 301).

Again and again, he will make the same assertion, on the one hand urging psychoanalysts to take greater responsibility for their concepts by having recourse to other fields, but on the other hand insisting that Freud’s discovery has produced a domain which must be grasped and developed as a field in its own right. In the case of Saussure, he insists that psychoanalysis stands in need of the conceptual resources that linguistics can provide, but this is not to turn psychoanalysis into a linguistic discipline. Psychoanalysis would therefore do well to consider the work of linguistics in more detail (and Lacan goes on to link substitution and displacement with metaphor and metonymy), and yet the conceptual task cannot end there, for Lacan immediately adds a twist: “Conversely, it is Freud’s discovery that gives to the signifier/signified opposition the full extent of its implications: namely, that the signifier has an active function in determining certain effects” (E/S, p. 284) – effects which concern the clinical register. The most obvious of these effects, which linguistics would hardly be required to consider, is the bodily symptom, which has a symbolic dimension for Lacan, as Freud already suggested when he ascribed the hysterical symptom, not to organic dysfunction, but to the activity of unconscious representations, saying “hysterics suffer mainly from reminiscences” (SE 2, p. 7).

Following Freud, but also learning from Saussure, Lacan insists on the autonomy of the signifier, whose operation should not immediately be situated at the “psychological” level. For the “reminiscence” in this case is not a conscious or even merely an unconscious “memory,” in the usual sense of the word, and cannot really be grasped as a “psychic” phenomenon at all, but is rather a signifier that (1) has been detached from its signified (since, as Freud argues, the patient generally does not remember the pathogenic event – the “signified” – which has undergone repression, or been emptied of meaning, or replaced by an apparently “innocent” or “nonsensical” substitute), but at the same time (2) remains present, inscribed at the level of the body, such that the symptom remembers in place of the memory. The symptom, Lacan says, is “the signifier of a signified repressed from the consciousness of the subject,” and “written in the sand of the flesh” (E/S, p. 69). The broader philosophical consequence is immediately evident here, for this also means that the symptom in psychoanalysis, in spite of its concrete physiological manifestation, can never be confused with a biomedical phenomenon of the kind that would have a correlate in the animal world, since it only belongs to the being who speaks, and whose very life is reconfigured when it passes through the network of the symbolic order – “which makes of the illness the introduction of the living being to the existence of the subject” (E/S, p. 69).

If this characterization of Lacan’s general stance is correct, it should not only guide us in reading his work, but also warn us against several interpretive shortcuts which have marked the secondary literature. For we can hardly be content with a cursory gesture that pretends Lacan produced a “Hegelian reading of Freud,” or applied “structural linguistics” to the unconscious, as though clinical considerations played no part in the formation of his concepts.21 Yet this very impression has been popularized by accounts which reduce Lacan to an amalgam of his sources, as though the “imaginary” relation and the question of narcissism could be translated back into the terms of intersubjective rivalry developed by Kojève, or as though Lacan’s understanding of the “symbolic” were imported without the slightest change from the field of structural anthropology.22 Such claims may satisfy our inclination to package and digest material that is notoriously difficult, and may even give us permission to avoid the challenge of his vocabulary, by recasting it in terms of a more familiar academic discourse; but such a translation will invariably obscure Lacan’s terminology and avoid the clinical dimension of his work, and in return, the philosophical resources on which he draws will never be genuinely affected by the transformation they undergo when they are placed in the context of psychoanalysis.23 The very challenge that is posed by the question of “psychoanalysis and philosophy” will have been eliminated altogether, in favor of a reception that makes Lacan’s work recognizable, but at the cost of eliminating the specificity of the field in which he operates.

Consider the distinction between “need” and “desire.” Lacan borrowed this distinction from Kojève, who insisted that human desire, which Kojève called “anthropogenetic desire,” is essentially a “desire for recognition,” and is therefore fundamentally different from “animal desire,” which Lacan called “need,” and which is modeled on an instinctual relation to the object and the requirements of biological survival (the classical example being the “need for food”). The animal’s relation to the object of need is thus usefully distinguished from the human relation to the other, which is fundamentally a relation to the other’s desire. Hence the famous formula Lacan absorbs from Kojève: “Man’s desire is the desire of the other.” This is all well and good, but Kojève’s conceptual framework does nothing to clarify Lacan’s distinction between “desire” and “demand” (as is evident from the fact that the secondary literature speaks indifferently of a “demand for recognition” and a “desire for recognition” as though there were no difference between the two). The appeal to Kojève’s framework thus obliterates the distinction between demand and desire in the very gesture that offers to explain Lacan’s work. Nor does the reference to Kojève help us to grasp the Freudian problematic of the “object-relation.” Starting from the philosopher’s distinction between the human and the animal, we can speak of the peculiar character of “recognition” and “intersubjectivity” in the human sphere, but when it comes to the object-relation and the question of bodily satisfaction, the Kojèvean framework leaves us at a loss, by presupposing that the bodily “relation to the object” is always a natural or “animal” relation (as with the “need for food”). To be sure, the commodity presents us with an “object-relation” that escapes from the order of need, but in this case, the fundamental function of the object is to mediate a relation to the other’s desire (the commodity only rises above need to the extent that it has a symbolic function in relation to the other), and in this sense, the entire discourse of “recognition” and “intersubjectivity” short-circuits the clinical problem of the “object-relation.”

This is especially important when it comes to the problem of embodiment. In the case of the satisfaction of the oral drive, for example (to stay with the Kojèvean example of food), the subject departs from the order of biological need, and may eat too much, or refuse to eat at all. Such a phenomenon, which Lacan would characterize as a bodily demand – an oral demand in which the desire of the subject is compromised – leaves the philosopher silent. In short, from Kojève’s perspective, the “human” or “anthropogenetic” relation is deftly explained at the level of intersubjectivity, but the “body” as such is prematurely relegated to nature and animality, in keeping with a long philosophical tradition. As a result, the question of sexuality, the symptom, and the libidinal organization of the body – all of these issues, which were so crucial to Freud’s thinking, are simply cast aside, displaced in favor of a disembodied discourse on the “relation to the other.” And in this way, the terminology of psychoanalysis (“the other” or “the symbolic”) is devoured or incorporated by philosophy, integrated into a familiar discourse on “recognition” as though psychoanalysis made no intervention whatsoever in the vocabulary it borrows from other domains. A relation to the other, indeed. In place of a genuine encounter, the discourse of psychoanalysis is simply reabsorbed by the philosophical tradition, and the problems that animate Lacan’s theoretical development are abandoned in favor of a conceptual arrangement that is already established in the academic discourse of post-modernism. Paradoxically, then, the popular demonstration of Lacan’s debt to philosophy, while it promises to elucidate his work, has tended not only to avoid Lacan’s most important conceptual innovations, but also to promote the erasure of the psychoanalytic domain as such.

Generally speaking, the central problem in the reception of Lacan in the English-speaking world has been the mobilization of an interpretive machinery on the part of readers who simply do not know enough about psychoanalysis, and for whom the erasure of the clinical domain takes place without even being noticed. But this difficulty is also something for which psychoanalysis itself is responsible. For the psychoanalytic community has often been all too reluctant to develop its conceptual apparatus in a way that would speak to other disciplines – though Freud himself obviously had such ambitions for his work. This is perhaps understandable, since the principle interest of psychoanalysis rightly rests with its own internal affairs, and not with an exposition of its consequences for another field. Thus, if the Lacanian concept of the gaze develops in dialogue with Merleau-Ponty, the task of the analyst is not to demonstrate the effects of this concept on the phenomenological account of perception, but simply to refine the theoretical framework of psychoanalysis itself, and to grasp what Lacan means when he characterizes the gaze as an “object of the drive.” And yet, Lacan’s work does have consequences for other fields which are worthy of greater exposition, as in the cases of Kojève and Saussure.

This same difficulty could be traced across an entire range of thinkers. We have seen how Lacan was “influenced” by Heidegger, and how he referred to the philosopher on many occasions. But we do not yet know how Lacan’s discussion of anxiety, based as it is on a clinical problematic (the logic of the relations among anxiety, jouissance, and desire) and a reading of Freud’s work, might challenge the philosopher’s account of Being-in-the-World. Is anxiety, in the peculiar relation to death which it discloses, together with the ex-static temporality it reveals, the manifestation of our fundamental and authentic mode of being, as Heidegger suggests, or is it in fact a transformation of libido, or perhaps rather a disposition of the ego in the face of some danger, as Freud argues? Or is it still rather a particular moment in the relation to the Other, a mode of jouissance in which the desire of the subject is suspended, as Lacan claims in his analysis of Abraham and Isaac? In order to begin to answer such questions, the philosopher would have to read the texts of psychoanalysis with a view to grasping the clinical stakes of these issues. A simple documentation of the references Lacan makes in passing to the texts of Kierkegaard, Heidegger or Sartre will do nothing to clarify such questions, but will only perpetuate the vague idea that Lacan somehow borrows the idea of “being-towards-death” from his philosophical rival. In this way, the encounter between philosophy and psychoanalysis will once again be missed.

Even among Lacanians, who are generally more engaged with conceptual developments in other fields, a genuine encounter with philosophy has been largely circumvented, as is evident in the secondary literature, where a gesture of expertise among devotees has tended to dismiss the philosophical tradition as an arena of benighted confusion. This is, of course, the strict counterpart to the recuperative gesture of academic knowledge, which delights in demonstrating the absolute dependence of Lacan on the thinkers to whom he refers (“once again, the shadow of Hegel falls over the corpse of Lacan’s terminology”). These gestures of authority and debunking (“Lacan alone can explain what all previous thinkers misunderstood,” or “Lacan merely quotes and recapitulates an assemblage of sources”) are the predictable signs that a disciplinary boundary is simply being protected, and has yet to be traversed in a mature fashion – which only indicates that important work remains to be done. But even this hasty survey suggests that Lacan’s own procedure was more open, and that he read the texts of philosophy with a seriousness of purpose, and with a willingness to have his own concepts challenged, while at the time preserving the specificity of his task, and the difference between the clinical and philosophical domains.

By the same token, therefore, it would be a mistake to conclude that Lacan’s own system is a self-contained apparatus, an interpretive juggernaut that can be mechanically applied to every other conceptual field – as though the categories of the Imaginary, Symbolic, and Real, having established themselves with dogmatic certainty, could now be unleashed on painting, cinema, Yanomamo culture, theories of democracy, or contemporary debates about ethnicity and national identity, without the theory itself developing in response to the fields with which it engages. If there is traffic between philosophy and psychoanalysis, it does not move in only one direction. When one follows the procedure of Lacan himself, and his often labyrinthine protocol of reading, it is clear that the self-sufficiency of the Lacanian system – however satisfying it may be for his followers to deploy – was never so secure, and that Lacan himself insisted on this long detour into foreign philosophical territory, not to demonstrate what he already knew, but to develop his own conceptual apparatus through the challenge of this other domain.

Lacan turned to other thinkers, then, neither to demonstrate their failure to arrive at properly psychoanalytic conclusions, nor to deploy his own categories, repeating on other terrain the conclusions he had already reached, but rather because the psychoanalytic community had not done enough to refine its own conceptual domain, and stood to gain from a sustained encounter with its neighbors. His turn to philosophy was therefore neither an abandonment of psychoanalysis in favor of Structuralism or anthropology or philosophical discourse (since he is not ultimately interested in solving philosophical problems), nor simply a matter of stealing from others (since the concepts he finds are invariably altered when they enter the domain of psychoanalysis); nor, finally, did he aim at the sort of self-enclosed system that could serve as the intellectual trump card in relation to other knowledge. This is the great gift bequeathed to us by Lacan’s often infuriatingly difficult work: one can no more be content with a superficial glance at “the famous being-towards-death,” tossed off on the way to a demonstration of Lacan’s superiority to every other thinker, than one can retreat into the haven of familiar formulae drawn from Kojève and Saussure.

This double gesture is the fundamental mark of Lacan’s relation to the philosophical arena – maintaining without compromise the theoretical specificity of the psychoanalytic field, which has its own complex and often technical vocabulary, and develops in response to a distinctive clinical field, and yet taking full responsibility for the articulation of its concepts, by a rigorous engagement with other relevant domains, as the earliest analysts themselves were always careful to do. The persistent exploration of this disciplinary border, and the double movement it entails, is the hallmark of Lacan’s relation to other areas of knowledge: “In a discipline that owes its scientific value solely to the theoretical concepts that Freud forged . . . it would seem to me to be premature to break with the tradition of their terminology. But it seems to me that these terms can only become clear if one establishes their equivalence to the language of contemporary anthropology, or even to the latest problems in philosophy, fields in which psychoanalysis could well regain its health” (E/S, p. 32).

It is clearly not possible to cover such a complex set of issues in a short space, but having sketched out the general terrain, let us now narrow our inquiry quite sharply and take up an example in a bit more detail, in order to see more concretely how Lacan works across various borders as his thinking unfolds. We will see how a number of threads are woven together, linking Aristotle’s Ethics, modal logic, and sexual difference in a strange but intriguing fabric. The complications of the argument are enormous, as will quickly become apparent, and we will do no more than outline a few of the pathways that are opened by this example – four paths, to be precise, before we conclude. But even this minimal sketch will be sufficient to give readers a more concrete sense of how Lacan’s thought intersects with the philosophical tradition.

In 1972–3, Lacan gave a seminar entitled Encore, in which his thinking about sexual difference takes a dramatic step forward. The text of this seminar, recently translated as On Feminine Sexuality, has had an enormous influence, not only within the Lacanian tradition, but in French feminist theory and in broader debates about gender and sexual difference in the Anglo-American context, due largely to the translation of a portion of the work in Jacqueline Rose and Juliet Mitchell’s anthology, Feminine Sexuality. In Seminar XX: Encore, Lacan famously develops an account of “feminine sexuality” – or more precisely of the “Other jouissance” – which seems to break with his earlier work. For in earlier years, Lacan had provocatively insisted upon maintaining Freud’s thesis that “there is only one libido,” and that this libido is “phallic,” arguing that what Freud meant thereby – though obviously he did not use this terminology – was that human sexuality is not governed by the laws of nature, and does not culminate in a “normal genital sexuality” which aims at procreation, but is rather governed by the symbolic order and the law of the signifier. As Freud said in Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality, there is no genital normalization leading to a proper biological object, but only a series of libidinal sites (usually located in relation to the bodily orifices) which are not mechanically situated in a natural development, but are shaped by psychic traces of memory and relations with others. Sexuality has a history in the human animal, rather than a simple evolutionary unfolding, precisely because it is not automatically bound to the mechanisms of natural development (so much for Steven Pinker). And this fact about sexuality holds for all speaking subjects as such, regardless of sex or gender: there is only one libido, and it is phallic, in the sense of being subject to the signifier. Where instinct provides animals with a biological grounding and a telos of reproduction, divided between two sexes, humans are faced instead with modes of libidinal satisfaction that are organized by representation. Without entering into the details of this discussion, we can nevertheless see why Lacan claims that “there is only one libido,” meaning that the satisfaction of the drive in human beings is detached from the order of nature, and subjected to a symbolic organization, such that the satisfaction of the drive is always caught up in the relation to the other, and the symbolic codification of the body.

The peculiarity of this position is that there seems to be no clear way of distinguishing between the sexes. And indeed this is Lacan’s position for many years: for psychoanalysis, sexuality is not divided into a “feminine” and “masculine” form, or structured according to the two biological “sexes” – as though biological difference might, after all, provide a foundation for this question, in spite of Freud’s claims to the contrary. Nor can one take comfort in the culturalist notion that the social codification of “gender” will somehow establish what nature fails to provide. Historically speaking, of course, various cultures indeed organize sexuality in many ways, and Lacan hardly ignored this fact. But the social dimension of “gender identity,” structured as it is at the general level of cultural practices and norms, is insufficient to tell us what psychoanalysis needs to know about the subject, whose relation to the symbolic order is always particular. Thus, while a given culture may well mobilize a host of images for femininity which offer an emaciated ideal of the body, we cannot conclude that every woman will automatically become anorexic in response, as if the subject were simply a social construction. Lacan’s “advocacy of man’s relation to the signifier has nothing to do with a ‘culturalist’ position in the ordinary sense of the term” (E/S, p. 284). “Gender” is thus a useful category for historical analysis, but from the standpoint of psychoanalysis, the subject’s sexuality will be fashioned in every case according to a distinctive organization, with particular modes of satisfaction, and this is why psychoanalysis, as a matter of methodical procedure, cannot take place in a classroom, or be transmitted like other forms of knowledge, but rather requires that each subject explore the singular discourse that defines each one alone. This is the great mystery of psychoanalysis, but also its philosophical importance, when it comes to sexual difference: the question of “sexual difference” cannot be resolved by any appeal to the usual categories of biological “sex” and cultural “gender.” And paradoxically, it is the thesis on “one libido” that helps to establish this claim.

In 1972, however, Lacan’s thinking takes a new step forward. Where he had previously insisted that the libido, in humans, is governed by the symbolic order and the laws of language – a “relation to the Other” which structures every subject, regardless of biological sex – he now proposes that there is more than one way of relating to this Other. Lacan even stresses the apparent contradiction this presents, in relation to his earlier work: “I say that the unconscious is structured like a language. But I must dot the i’s and cross the t’s,” and this means exploring not only the laws of the symbolic order, but also “their differential application to the two sexes” (S XX, p. 56). And he knows his audience will be stunned: “So, you’ve admitted it, there are two ways to make the sexual relationship fail” (S XX, pp. 56–7), he writes, two ways for the lack of genital normalization to be manifested. Such is the claim in 1972, and we can perhaps understand already why Lacan hesitates to designate this “second way” under the sign of “femininity,” since the customary usage of such a term would imply that we are dealing either with biological sex or with the broadly social category of gender identity, while in fact it is a question of another jouissance that appears with some subjects, but cannot be attached to a social or biological group as a whole (“women”), or even restricted, necessarily, to one gender or one sex: “There is thus the male way of revolving around it [i.e. the phallic way], and then the other one, that I will not designate otherwise because it’s what I’m in the process of elaborating this year” (S XX, p. 57). One understands the hesitation, then, but it is nevertheless clear that Lacan’s aim is to intervene in the classical psychoanalytic debate on sexual difference, through this thesis on a mode of jouissance that is “not-all in the Other,” or not wholly governed by the order of the “phallic” signifier: “it is on the basis of the elaboration of the not-whole that one must break new ground . . . to bring out something new regarding feminine sexuality” (S XX, p. 57).

This is our example, then, and in many respects, we can recognize it as an attempt to clarify some of Freud’s most famous remarks on femininity: for Freud observes that women have a different relation to castration, and indeed a different relation to the “law,” as his notorious claims about the lack of a super-ego in women (or, more precisely, the formation of a different super-ego in women) make clear. And Lacan elaborates these claims by suggesting that femininity entails the possibility (and I will already stress this word, possibility, in which sexual difference and modal logic come together – as though femininity were only a possible and not a necessary mode of being) of a different relation to the symbolic order, a relation that may have ethical as well as clinical consequences.

The debates about Freud’s views on “femininity” are obviously enormous, and we can do no more than mark the issue in a general way. Let us then simply recall Freud’s statement in “Some psychical consequences of the anatomical distinction between the sexes”:

I cannot evade the notion (though I hesitate to give it expression) that for women the level of what is ethically normal is different from what it is in men. Their super-ego is never so inexorable, so impersonal, so independent of its emotional origins as we require it to be in men. Character-traits which critics of every epoch have brought up against women – that they show less sense of justice than men, that they are less ready to submit to the great exigencies of life, that they are more often influenced in their judgements by feelings of affection or hostility – all these would be amply accounted for by the modification in the formation of their super-ego which we have inferred above.

(SE 19, pp. 257–8)

Whether one dismisses this statement as a stereotypical expression of the prejudices of Freud’s day, or celebrates it as an insight into the fact that sexual difference may have a bearing on ethical questions (such that femininity may make possible a “different voice” or an “ethics of care” – a sense of justice in which the rigidity of a masculine law is implicitly criticized), it is clear that Freud has opened a path that is at once clinical and philosophical, insofar as it points to a “modification” in the form of the super-ego (what Lacan would call a different relation to the law) that not only seeks to identify some aspects of psychic life, but also has implications for our understanding of what Freud calls “justice.” In Freud, the question of sexual difference is thus explicitly linked to ethics, and here again we should stress the double trajectory that Lacan has done more than any other figure in the history of psychoanalysis to maintain. For the interpreter’s task is complicated by the fact that the clinical field cannot be directly superimposed on the domain of philosophy: the “law” in psychoanalysis (and its “modification”) does not immediately coincide with the “law” in the philosophical domain, and cannot automatically be translated into a generalized discourse on ethics and the good. Nevertheless, if we recall that Freud himself spoke of the super-ego as the foundation of the moral imperative in Kant, we begin to see how clinical issues, forged on the terrain of psychoanalysis, might nevertheless have a legitimate impact on the domain of philosophy. With this example in mind, let us follow Lacan’s itinerary a little further.

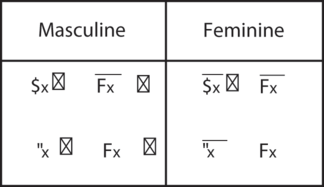

First path: the sexuation graph. Having taken this step towards the “Other jouissance,” in which the general law of symbolic castration is no longer the whole story, Lacan now develops Freud’s claim by means of symbolic logic, in the “sexuation graph” which maps out two modes of relation to the Other, correlated with sexual difference.

On the “male” side, the “normal” or “phallic” position is defined through the proposition that all subjects, being unmoored from nature, are destined to find their way through the symbolic order. Lacan expresses this claim in symbolic notation, with the formula  (“All subjects are submitted to the phallic signifier”). Now this position (the universal law of symbolic existence) is paradoxically held in place by an exception to the law, which Lacan elaborates in keeping with Freud’s analysis of the primal horde in Totem and Taboo, where Freud explains that the sons all agree to abide by the law (to accept symbolic castration), precisely in contrast to the “primal father,” who stands as the exception to the rule, in relation to which the law is to be secured. Thus, the “male” side of the sexuation graph includes another formula,

(“All subjects are submitted to the phallic signifier”). Now this position (the universal law of symbolic existence) is paradoxically held in place by an exception to the law, which Lacan elaborates in keeping with Freud’s analysis of the primal horde in Totem and Taboo, where Freud explains that the sons all agree to abide by the law (to accept symbolic castration), precisely in contrast to the “primal father,” who stands as the exception to the rule, in relation to which the law is to be secured. Thus, the “male” side of the sexuation graph includes another formula,  (“There is one subject who is not submitted to the phallic signifier”), and this second formula, which forms part of the law of castration on the male side, is cast as an excluded position, an exception to the law, as Freud also claims when he explains that the primal father must always be killed, since his expulsion from the community by murder insures that the symbolic community will be established. The two formulae thus appear to present a simple contradiction, logically speaking, but in a clinical sense they are intended to define the antinomy that structures masculine or phallic sexuality, in the sense that the exception to the law, where the possibility of an unlimited jouissance is maintained (

(“There is one subject who is not submitted to the phallic signifier”), and this second formula, which forms part of the law of castration on the male side, is cast as an excluded position, an exception to the law, as Freud also claims when he explains that the primal father must always be killed, since his expulsion from the community by murder insures that the symbolic community will be established. The two formulae thus appear to present a simple contradiction, logically speaking, but in a clinical sense they are intended to define the antinomy that structures masculine or phallic sexuality, in the sense that the exception to the law, where the possibility of an unlimited jouissance is maintained ( ), is precisely the jouissance that must be sacrificed, expelled, or given up for the field of desire and symbolic exchange to emerge. Such is the logic of symbolic castration. It would obviously be possible to play out this “logic of masculinity” in some detail, with reference to Arnold Schwarzenegger and others, whose films represent the masculine fantasy in which the law of the civilized community can only be upheld, paradoxically, by an exceptional figure who is able to command an absolute power of violence, which is itself used to expel the monstrous, mechanical, or demonic figure (the uncontrollable machine or corrupt corporate demagogue) whose absolute jouissance threatens the space of democracy and capitalistic exchange. In masculinity, democracy and totalitarianism are not simply contradictory, as though they could not exist together, but are on the contrary twins, logically defining and supporting one another. Such elaborations – always too quick in any case – are not our purpose here, but we can at least note Lacan’s attempt to provide a rigorous theoretical account, through symbolic logic, of the “contradictions” of masculinity.

), is precisely the jouissance that must be sacrificed, expelled, or given up for the field of desire and symbolic exchange to emerge. Such is the logic of symbolic castration. It would obviously be possible to play out this “logic of masculinity” in some detail, with reference to Arnold Schwarzenegger and others, whose films represent the masculine fantasy in which the law of the civilized community can only be upheld, paradoxically, by an exceptional figure who is able to command an absolute power of violence, which is itself used to expel the monstrous, mechanical, or demonic figure (the uncontrollable machine or corrupt corporate demagogue) whose absolute jouissance threatens the space of democracy and capitalistic exchange. In masculinity, democracy and totalitarianism are not simply contradictory, as though they could not exist together, but are on the contrary twins, logically defining and supporting one another. Such elaborations – always too quick in any case – are not our purpose here, but we can at least note Lacan’s attempt to provide a rigorous theoretical account, through symbolic logic, of the “contradictions” of masculinity.

Figure 8.1 Lacan’s sexuation graph

While the “masculine” side of the graph provides a relation to symbolic castration which is total (“All men are subject,” etc.), the “feminine” side, by contrast, provides a second pair of formulae in which the subject is not altogether subjected to the law. The second of these formulae,  can be read as “Not all of a woman is subject to symbolic castration.” The universal, which functions on the masculine side (“All men”), is thus negated on the side of femininity (“Not all”). Something of woman may thus escape symbolic castration, or does not entirely submit to the symbolic law (“they show less sense of justice than men” and “their super-ego is never so inexorable”). “Feminine jouissance” is thereby distinguished from “phallic jouissance” by falling partly outside the law of the signifier. Subjected to the symbolic order like all speaking beings, the “feminine” position is nevertheless “not-all” governed by its law. And as was the case on the masculine side, so here we find a second formula, but in this case it is not an exception to the law (as with the primal father). Instead, we find a formula that indicates an inevitable inscription within the law:

can be read as “Not all of a woman is subject to symbolic castration.” The universal, which functions on the masculine side (“All men”), is thus negated on the side of femininity (“Not all”). Something of woman may thus escape symbolic castration, or does not entirely submit to the symbolic law (“they show less sense of justice than men” and “their super-ego is never so inexorable”). “Feminine jouissance” is thereby distinguished from “phallic jouissance” by falling partly outside the law of the signifier. Subjected to the symbolic order like all speaking beings, the “feminine” position is nevertheless “not-all” governed by its law. And as was the case on the masculine side, so here we find a second formula, but in this case it is not an exception to the law (as with the primal father). Instead, we find a formula that indicates an inevitable inscription within the law:  (“There is no subject that is not subjected to the symbolic law”). These formulae have been much discussed, and there is no need to rehearse the literature here. But since we are exploring the way in which Lacan uses symbolic logic to sharpen some issues in the debate on sexual difference, and to account for its peculiar “paradoxes,” it is worth noting that in this second formula, which articulates the feminine version of subjection to the law, we do not find a universal proposition, a statement that could be distributed across all subjects (“All men,” etc.). Instead, we find a formulation that relies on the particular (“There is no woman who is not” etc.). The universal quantifier “all” (

(“There is no subject that is not subjected to the symbolic law”). These formulae have been much discussed, and there is no need to rehearse the literature here. But since we are exploring the way in which Lacan uses symbolic logic to sharpen some issues in the debate on sexual difference, and to account for its peculiar “paradoxes,” it is worth noting that in this second formula, which articulates the feminine version of subjection to the law, we do not find a universal proposition, a statement that could be distributed across all subjects (“All men,” etc.). Instead, we find a formulation that relies on the particular (“There is no woman who is not” etc.). The universal quantifier “all” ( ) is thus replaced with a quasi-existential “there is” (

) is thus replaced with a quasi-existential “there is” ( ) which any reader of Heidegger or Derrida will recognize is immensely rich and complex – the il y a (or “there is”) in French being also the translation of Heidegger’s es gibt, in which a massively complex meditation on the “givenness” of Being can be found. With Lacan, then, there is a link between the mode of being of femininity – which does not appear or give itself in the universal, and is not entirely inscribed within the symbolic law – and the question of Being itself. And the form of symbolic logic brings these issues prominently to the surface.

) which any reader of Heidegger or Derrida will recognize is immensely rich and complex – the il y a (or “there is”) in French being also the translation of Heidegger’s es gibt, in which a massively complex meditation on the “givenness” of Being can be found. With Lacan, then, there is a link between the mode of being of femininity – which does not appear or give itself in the universal, and is not entirely inscribed within the symbolic law – and the question of Being itself. And the form of symbolic logic brings these issues prominently to the surface.

An enormously tangled set of issues thus emerges, and one can see how Irigaray took up this challenge, linking femininity to questions of being and language. And angels.24 For Lacan remarks on the “strangeness” of this feminine mode of being: it is étrange, Lacan says, playing on the word for “angel” (être ange means “to be an angel”), this mode of being which falls outside the grasp of the proposition (“it is . . .”). We cannot say that “it is” or “it exists,” just like that, because it does not all belong to the domain of symbolic predication, and yet, this same impasse in symbolization means that we cannot say “it is not” or it “does not exist” (or indeed that “there is only one libido”). Beyond the “yes” and “no” of the signifier, beyond symbolic predication and knowledge (is/is not), this mode of being, presented through the Other jouissance, would thus be like God, or perhaps (peut-être – a possible-being) more like an angel. Thus, as Lacan suggests, and as Irigaray also notes, though in a very different way, the question of feminine sexuality may well entail a theology and an ontological challenge in which the law of the father is not the whole truth. “It is insofar as her jouissance is radically Other that woman has more of a relationship to God” (S XX, p. 83).

In these formulae for femininity, moreover, we again find a curious use of negation, for the strange “there is” of femininity, already detached from the simple assertion of existence, is also presented only under the sign of a certain negation (“Not all of a woman is . . .”). Even in the first formula, we are faced with a double negation (“There is no woman who is not”). This is very different from what we find on the masculine side (“All men are . . .”). “It is very difficult to understand what negation means,” Lacan says. “If you look at it a bit closely, you realize in particular that there is a wide variety of negations” and that “the negation of existence, for example, is not at all the same as the negation of totality” (S XX, p. 34). Thus, we cannot regard the feminine formulation for symbolic inscription (“There is no woman who is not subject to the signifier”) as the equivalent of its masculine counterpart (“All men are subject to the signifier”), even though logically these two may be the same. In fact, sometimes a thing can “appear” or “exist” only by means of a kind of negativity (“there is . . . none that is not . . .”), particularly if the “normal” symbolic discourse of propositions (“All men are”) already presupposes a mode of being or existence that is itself inadequate. The vehicle of symbolic logic thus seems to force to the surface a variant in the mode of negation that ends up bearing on sexual difference. Woman does not “exist,” then, and yet “there is” femininity. We cannot say, in the form of a symbolic assertion, that she “is” this or that (a subject with a predicate that would cover the field of “all women,” and allow us to capture her essence as a social or biological totality), and yet it is “possible” that “there is” something of femininity, which has precisely the character of not being fully inscribed in the signifier – a being in the mode of “not-being-written,” Lacan says. “The discordance between knowledge and being is my subject,” Lacan says (S XX, p. 120). Lacan does not say that woman “exists,” then, or indeed that she “is not,” but rather that she ex-sists: “Doesn’t this jouissance one experiences and yet knows nothing about put us on the path of ex-sistence?” (S XX, p. 77). All of this may seem far removed from the clinical field we have stressed, and yet it is clear that many experiences, from practices of meditation or ecstatic dance to the paralyzing encounter with absolute solitude into which no other can reach – a black hole of truth from which no words can escape – all testify to a place on the margin of language where enjoyment and exile await us all. Thus, while the I may belong to speech, not all of the subject is inscribed there. As Lacan says: on the one hand, “the I is not a being, but rather something attributed to that which speaks”; but on the other hand, “that which speaks deals only with solitude, regarding the aspect of the relationship I can only define by saying, as I have, that it cannot be written” (S XX, p. 120).