Falls don’t “just happen,” and people don’t fall because they get older.

—NIH Senior Health website

I can’t remember first learning to walk with balance—I was only a year old—but I can tell you that my life changed dramatically after I mastered that skill. Balance is vital at any age, and although it seems like goldeners are special in that they really need to work on their balance, I can tell you from working with thousands of people that many, of all ages, aren’t really walking in an efficient, balanced way. Age isn’t solely responsible for a dramatic loss of balance—the problem is more a sedentary lifestyle where you haven’t practiced balance in a long time. That all said, the consequences of falling are greater once you pass the bouncy-tissue age of two, and so it’s no wonder many goldeners carry with them a fear of falling that permeates all of their movement decisions.

Joyce Says

Joyce Says

I was sixty-eight when I realized I no longer felt safe on a ladder picking oranges from our orange tree. I didn’t believe it at first, but on repeated attempts, I could not change the feeling of unsteadiness and fear when I attempted to mount the ladder beyond the first or second rung. The loss of my sense of balance was unmistakable. I felt a heavy resignation and thought to myself, “Oh, this is what it’s like to age.”

A few years ago I visited Taos Pueblo in New Mexico. On a tour I learned that the original buildings had no doors—and that tribal members of all ages (thought to be up to fifty or sixty) had to get into their home by climbing up a ladder to the roof and then down another ladder into the dwelling. While they didn’t live as long as many of us do now, they maintained the ability to climb ladders with ease their entire lifespan. And that’s when I started to merge my understanding of exercise science with my understanding of anthropology—getting up and down a ladder is made more challenging simply by the fact that we rarely use ladders and that the moves we do with confidence are simply the moves that we do multiple times a day. Thus, it’s easy to see how one could mistake the wobbliness that comes from many decades of very little movement with the accumulation of the decades themselves.

Despite “age” seeming to be the obvious cause of so many falls, age itself isn’t a maker of falls, according to the National Institutes of Health. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggests that one first address the following movement-related risks:

• A sedentary lifestyle

• Lower-body weakness

• Foot problems

• Gait and balance difficulties

As my good friends and co-contributors to this book will tell you, their experience of muscular weakness was not a result of aging so much as a result of decreased movement over a number of years. We live in an age of technology. Technology that’s been slowly increasing in scope and reducing our needs for movement. It’s very likely that the instability you are feeling is not due to your age, but to how long you haven’t been challenging your balance.

ENTER FEAR OF FALLING

Another risk factor for falling is the fear of falling. Meaning that simply being afraid of a fall (or its imagined aftermath) is enough to change the way we move.

If you’ve experienced a fall, it’s natural to be wary of another. Still, studies done over a two-year period found that while a feeling of unsteadiness coupled with previous falls was a large contributor to fear, 18 percent of the “fearful” group had a large fear of falling without having fallen before (Lach 2005).

Researchers, trying to determine whether a fall creates fear or fear creates a fall, discovered that people who hadn’t fallen, but reported a fear of falling, were more likely to fall in the future—despite the fact that they had decreased their activity level to reduce the opportunity for a fall (Friedman et al. 2002).

“People who hadn’t fallen, but reported a fear of falling, were more likely to fall in the future.

This is a sample of a wide body of work demonstrating that fear in itself is a risk factor for falling. The next question is, of course, why? Or perhaps more pertinently, how?

There is a generalization we can make about goldeners’ gait—that it becomes a slow, careful shuffle, easily recognized. What may come as a surprise is that research shows this way of walking—short stride lengths, shuffling feet, and low speed—is for the most part without a mechanical cause; it involves self-induced adjustments (Herman et al. 2005). In fact, gait disorders of this kind—in healthy seniors with no disease, previous falls, or weaker muscles than their counterparts—were largely a response to fear alone.

Of course, it’s perfectly natural to change how you walk in response to a fear of falling. When I moved from sunny California to my first icy Washington winter, I adopted a very similar way of moving to the one described above. I walked more slowly. I turned my feet out, bent my knees a bit to lower my center of gravity, and I started shuffling. When I recently paid attention to how I walked in a situation where I felt vulnerable to a fall, I noticed it wasn’t only my lower half adjusting. My neck and shoulders stiffened. My hands stiffened too, and so did my face. Anyone who’s walked over a slippery surface or spent any time on the ice or snow has likely altered their movement patterns to prevent a fall; these changes are a natural response to fear. But I want you to consider this for a moment: We’ve essentially mislabeled “scared gait” as “senior gait.”

The way we walk has a profound impact on the muscles used while walking and vice versa. When you shuffle, you’re not moving your ankles much, and so the muscles that facilitate ankle movement adapt by stiffening. Now your ankles can’t move when you need them to. When you bend your knees slightly all the time to keep your body mass low, you work the muscles down the front of the leg a lot, but you also reduce the work of the hips, giving you tight thigh muscles, but weak and stiff hips and, quite possibly, lower bone mass in the hips as well.

Adjusting the way you walk to reduce your fall risk in times of actual increased risk can serve you well. But “walking afraid” with every step doesn’t, in the end, protect you from falls. It weakens your body in ways that actually make you more susceptible to falls in the long run.

The key to reducing your risk of falling is to strengthen your body in a way that gives you a confident gait, which in turn strengthens your body even more, and so on.

It’s Not the Fall, It’s the Faller

A fall is not an issue in and of itself. Humans fall all the time without equal penalty. The impact of a fall has more to do with the state of the body doing the falling—the interface between a body and a particular surface. Robust tissues—supple muscles and ligaments, strong bones, and the ability to quickly adjust your shape—hold the potential to reduce the impact of a fall.

For this reason I suggest improving not only your balance and stability, but also your joint mobility, muscle mass, and bone density. This seems like it will take a lot of different exercises, but here’s the good news: The exercise program in this book addresses all of these at once. I don’t only want you to learn to balance on one leg; I want you to do it in a way that uses the muscles in the hip, which will then pull on bones of your hip, signaling “grow stronger.” If it seems like I’m getting a little nitpicky in my form requirements for each exercise, it is only because this form targets multiple issues at once, so that many issues can be improved from the same set of exercises.

YOU ARE HOW YOU WALK

More stable walking begins with your feet, which we began working on in chapter 1. After you’ve warmed up the toes and bones within the feet, it’s time to address the ankles.

Stable walking requires a lot of ankle mobility. The stiffer your ankles, the more you have to either shuffle or lift your entire foot away from the ground at the hip—both of which leave you more vulnerable to falls. Walking heel-toe allows you to transfer your weight from foot to foot in a more controlled manner, and it keeps your calf muscles supple and strong.

FEET FORWARD

In order to fully use your ankles while walking, your feet need to point forward, more like tires on a car, and less out to the sides like a duck. Align the outside edge of each foot with a straight edge, like a book or the seam of a carpet. When you straighten your feet, you’ll likely feel your knees and hips turn as well (see pages 106–107 for an additional step if you’re feeling knock-kneed). You’ll be using this forward foot position for most exercises in this book and can start working it into your walk. DON’T force your feet forward while walking, but instead pay attention to just how far your feet turn out and shoot for slightly less when you walk (an adjustment that’s shown to decrease the angles of the knee associated with knee osteoarthritis) (Shull et al. 2013).

Practicing a Fall

The greatest fear of all may be fear of the unknown, and since after childhood we fall so infrequently, falling is a big unknown for us. Because we’re afraid and have so little experience with falling, we tend to tense up rather than relaxing when we do fall, which changes the forces created by a fall.

A goldener named Elliott Royce set out to change that. At the age of ninety-five, he was falling five times a day—on purpose. Just as professional athletes practice drills over and over until their movements are almost reflexive, Royce intentionally fell onto an air mattress repeatedly to train his body to fall in a way that would reduce the impact of the fall on his body. From a Star Tribune article about his method:

“The secret to falling safely is three words: bend, twist, roll,” he said.

As you start to fall, bend your knees in the direction you are falling and twist at the waist, turning your shoulders away from the fall. That will change the point of impact. Instead of one spot on your hip taking the entire brunt of the fall, the force will be spread out along the length of your leg, thigh and pelvis. When you hit the ground, roll to further dissipate the force of the impact.” (Strickler 2015)

Royce’s approach to aligning his fall, which he taught to other goldeners, makes sense. When he had real falls—and he did—his body automatically responded in a protective way. Being leery of a fall is different from being afraid of one. Put your fear to rest by building a more robust structure and approach a physical therapist or movement teacher to help you institute your own “sage falling” practice.

CALF STRETCHES

The calf muscles are what often limit full motion of your ankle. These exercises are an excellent way to address tight calves!

CALF STRETCH #1

The first Calf Stretch targets the calf muscle that runs behind the knees, which is why you need to keep the knee straight on the stretching leg. To bend it is to diminish the stretch.

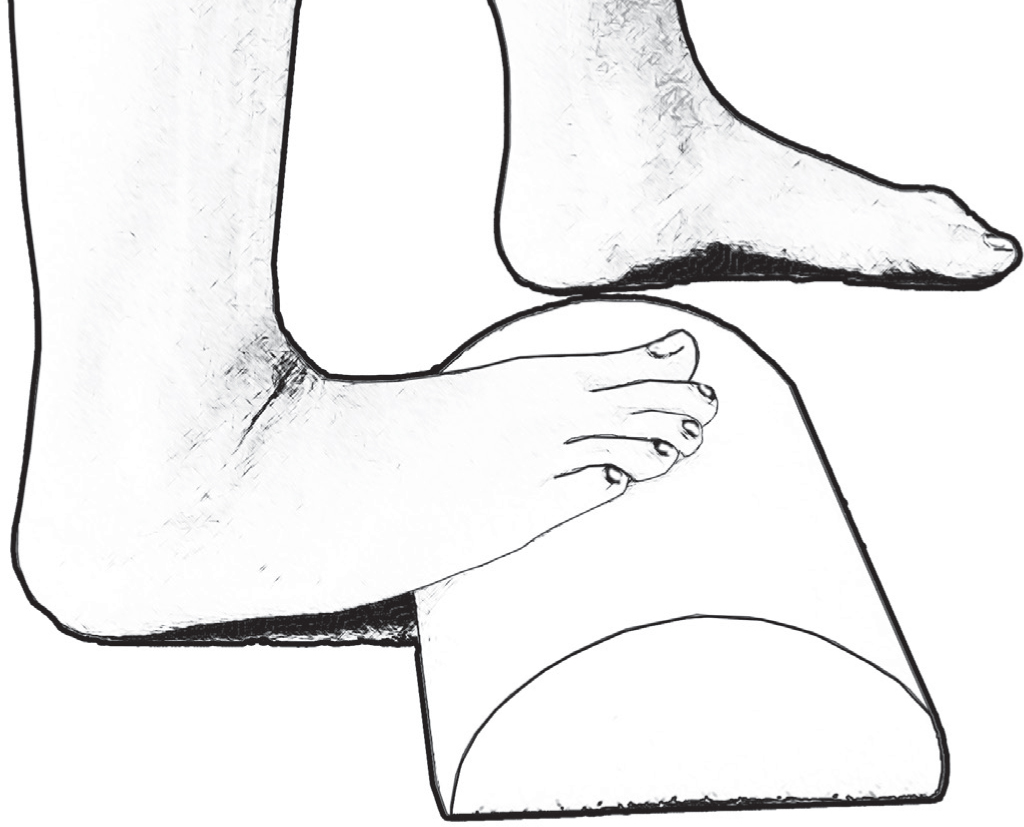

With a wall or chair close by for balance assistance, place a thick folded and rolled towel (or a rolled yoga mat) on the floor in front of you. Step onto the towel with a bare or socked foot, placing the ball of the foot on the top of the towel and keeping your heel on the floor.

Joan Says

Joan Says

A couple years after starting to do the Calf Stretch at least twice a day, morning and night, I noticed an interesting change in my hiking. Previously when I hiked uphill, I usually landed on the ball of my front foot because I couldn’t put my heel down. After lots of Calf Stretch practice, the range of motion in my ankles increased until I could land on my heels as I stepped uphill. This changed the muscles I was using to go uphill from my quads (on the fronts of my thighs) to those on my backside (hamstrings and butt). Katy had said using the hamstrings and glutes while walking (she calls it a “posterior push-off”) could help build a butt or retrieve one that was disappearing. And she was right! That is exactly what has happened to me. My co-authors and others who have known me for a while have commented over these past several years about the noticeable development of my gluteal muscles. In addition to moving with better strength and stability, I’m appreciating how I firmly fill out the back pockets of my pants.

Adjust the foot so that it points straight forward, and slowly straighten your stretching leg.

Keeping your body upright (try not to lean forward with your torso), step forward with the opposite foot.

The tighter your lower leg, the harder it will be to step in front of your stretching leg. It’s common to keep the non-stretching leg behind the towel at first. If you’re leaning forward, finding you need to bend your knees, or losing your balance, shorten your stepping distance.

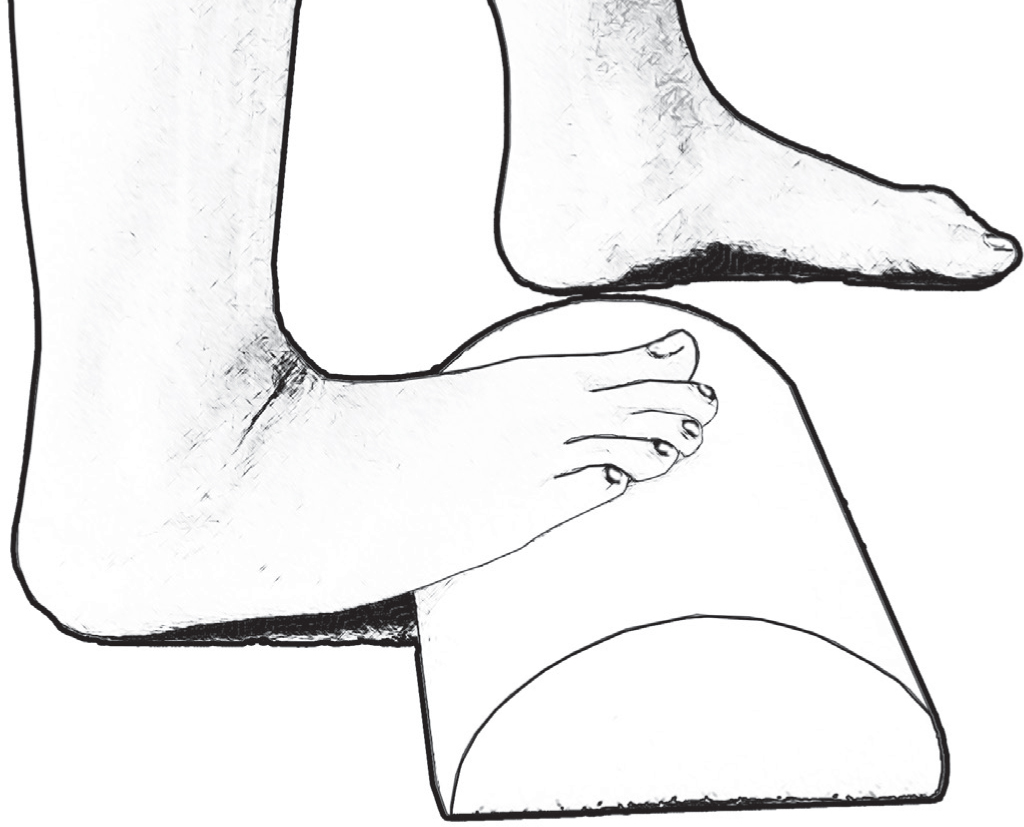

If you want to make the move more advanced, use a half foam roller instead of a rolled towel.

Lora Says

Lora Says

I’ve been in love with my half foam roller from the start. I had immediate success with the disappearance of restless leg syndrome, and as the half foam roller was my only new exercise prop at the time, I credited the dome with that miracle. After that first movement session I began a now seven-year habit of keeping a half foam roller in my kitchen. I have four-course mornings of breakfast, mind-strengthening games, keeping up with current events, and doing the Calf Stretch—it all keeps me feeling well nourished!

CALF STRETCH #2

This second Calf Stretch targets the deeper muscle in the calf group—the soleus—that affects the mobility between the foot and the shin. You get to bend your knee for this one!

Beginning in the position of Calf Stretch #1, bend the knee of the foot on the rolled towel, pushing it slightly forward as you press that same heel toward the ground.

Both calf exercises are designed to improve the ease of ankle movement when walking on flat ground and uphill.

Moving well requires the ability to walk comfortably, which requires balance, which depends heavily on the strength of a particular group of muscles: those of the lateral hip—which brings us to our next chapter.

Joyce Says

Joyce Says

Within a few years of starting to work with Katy, I once again was able to climb ladders and step ladders without fear. It was a marvelous feeling of personal power that I am grateful for. In the past few years, I have realized that once again I can climb stairs, go down stairs, climb mountains, go down mountains, skip, hop, jump, and leap for fun and also when I need to. I can squat, sit on the floor with comfort, sleep on the floor with comfort, kneel, hang from trees, swing on bars. These are all movements I took for granted as a child and up until somewhere in midlife, when these were no longer a part of my movement patterns.

Joyce Says

Joyce Says

Joan Says

Joan Says

Lora Says

Lora Says

Joyce Says

Joyce Says