THE HISTORY OF THE THEATER during the Middle Ages is obscure. Ancient drama seems to have disappeared, although it is possible that traces of Roman comedy may have been retained in the popular farces and other pieces performed by strolling bands of players and (later) by the jongleurs. So far as our actual knowledge goes, however, the significant theater of the Middle Ages is religious.1 It develops within the liturgy and emerges only partially from the church in the fifteenth century. In the West, two stages of this religious theater are to be distinguished: the liturgical drama (from the eleventh to the thirteenth century and later) and the mysteries (chiefly from the fourteenth to the sixteenth century, with later revivals).2 We shall give first a brief summary of their course and then a somewhat more detailed description of the features of each.

The origin of the religious theater appears to have been the practice of performing certain portions of the service dramatically—that is, the officiating priests actually representing the characters rather than merely narrating the events. This technique was first applied to the story of the Resurrection, and soon after to that of the Nativity. Around the original kernel there was a steady growth by accretion: in the Resurrection dramas the episode of the two Marys at the tomb of Christ (Matt. 28:1–7) was preceded by the scene of the buying of the ointment and followed by scenes representing the appearance of the risen Christ to the women and later to the apostles; the story was then extended backward to include the Crucifixion, the trial, and eventually all the events of Passion Week. Similarly, in the Nativity dramas the scene of the shepherds worshiping at the manger was expanded by taking in the Annunciation, the flight into Egypt, the Massacre of the Innocents, and so on.

Before this process of accretion was completed, the drama had been removed from its primitive position as part of the church service and reserved as a special feature of feast days, often coming as the climax of a procession and being performed on the church porch or steps—still, however, with priests and clerics as the actors, though the people might take part as a chorus. Next, the vernacular began to replace Latin; stage properties and costumes grew more elaborate; and with the constantly increasing size of the spectacle, the charge of the performances was finally given over to guilds of professional actors, and the arena of the action changed from the church to the marketplace. This transformation of the liturgical drama from an ecclesiastical to a municipal function was completed by about the middle of the fourteenth century and led into the mysteries, a typical late medieval form of sacred drama. But alongside the latter, the tradition of the older, simpler form survived; its traces are to be found in such works as the “school dramas” (plays on sacred subjects performed in schools and colleges), the oratorio, and certain aspects of opera in the seventeenth century, especially in Rome and northern Germany.

The Liturgical Drama

Like Greek tragedy, the liturgical drama grew out of religious ceremonies.3 The origin of the principal group of these, the Resurrection dramas, is found in the Quem quaeritis dialogue, of which the earliest surviving examples come from the tenth century:

Interrogatio: Quem quaeritis in sepulchro, o Cristicolae?

Responsio: Jhesum Nazarenum crucifixum, o celicolae.

Responsio: Non est hic, surrexit sicut praedixerat; ite, nunciate quia surrexit.4

This dialogue seems to have constituted an independent ceremony, for it is not uncommon to find it associated with more than one liturgical situation within the Easter rites. In one tenth-century manuscript, for instance, the Quem quaeritis dialogue appears as part of the Collecta ceremony; in another, it occurs at the end of Matins, just before the Te Deum laudamus.5 The Quem quaeritis dialogue was sung, not spoken. In fact, in the earliest liturgical dramas, everything was sung, but the further these plays grew away from the church, the more speaking and the less music they included, thus approaching in form the later mysteries.

The music of the liturgical dramas is of two kinds. One involves nonmetrical plainsong of a simple though not purely syllabic type. For texts taken from the liturgy or the tropes, the existing melodies were usually retained, either intact or in a “mosaic” made by selecting and combining fragments of the traditional chants. For the added portions, other melodies were selected or composed. The other kind has songs of a more or less distinctly metrical character, either hymn melodies or perhaps tunes of popular origin. These are less common, but they tend to occur more frequently in the later dramas. Their rhythm is not evident from the original notation but is apparent from the metrical form and presence of a rhyme scheme in the texts. The latter are usually strophic, with two to fifteen or more stanzas, and may be either in Latin or in the vernacular. Some of these songs may have been sung by the congregation.

There are songs for both soloists and chorus. In the earlier dramas they may have been accompanied by the organ; occasionally other instruments are mentioned, and it is probable that instruments of many kinds were used much more extensively in performance than the manuscripts themselves indicate. Most of the music is written as single-line melody, though there are occasional passages in two or more parts. The term conductus, which sometimes occurs, refers not to a musical form but to the procession from one part of the area where the drama is staged to another, marking the division of the drama into scenes.

More than two hundred liturgical dramas have been preserved, many of them available in modern editions.6 The subjects of these cover a wide range: the Resurrection, the Nativity, miracles of saints, the prophets (for example, Daniel), a melodrama with a kidnaping (Le Fils de Guédron), and a comedy (Le Juif volé). Adolphe Didron has pointed out that the liturgical drama must have represented for the medieval church a visible embodiment of the sacred stories commemorated in the statues and stained-glass windows of the cathedrals, as though the figures in these monuments “descended from their niches and panes … to play their drama in the nave and choir of the vast edifice.”7 There is about them certainly an air of profound and simple piety, a naive blending of sacred and profane without the least sense of incongruity, which is one of the most engaging features of medieval art.

The oldest extant morality play is the twelfth-century Ordo Virtutum (The Play of Virtues).8 Both text and music were written by Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179), the abbess of a convent in the Rhineland that observed the rule of St. Benedict. Although it is not known when or how the play was performed, it has been suggested that it was used to inaugurate the independent convent founded by Hildegard at Rupertsberg in 1152 or was staged in connection with the profession of novices at the convent.9 The play depicts the archetypal Soul (Anima) in its struggle with the Virtues, who represent the ideals of monastic life, and with the Devil, who offers the delights of the secular world. All the dramatis personae have singing parts except the Devil, the only solo role assigned to a man, who is restricted to a speaking part.10 This distinguishing feature was Hildegard’s way of aurally defining her conception of music as an expression of God’s perfection.

Ever since the Ordo Virtutum emerged from its veiled obscurity of more than eight hundred years, it has received numerous staged productions and now rivals in popularity the thirteenth-century Danielis Ludus (The Play of Daniel).11 These modern-day productions frequently color the notated monophonic chants with improvised instrumental music in the belief that this would have occurred in performances put on by the sisters of the Rupertsberg convent, where the playing of instruments was not only allowed but encouraged.

The Mysteries

The mysteries (the word is probably derived from the Latin misterium, “service”) flourished during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. They differed considerably from the earlier liturgical dramas. Although the church still collaborated and the bishop’s permission was necessary for a performance, the sponsor was the community as a whole and the actors were recruited from professional guilds, such as the Confrérie de la Passion in France and the Compagnia del Gonfalone in Italy.12 National differentiations are evident and the vernacular is used consistently. The Italian works of this class were known as sacre rappresentazioni, and generally regarded as forerunners of the oratorio, though their influence is apparent in some seventeenth-century Italian operas as well.13 The subjects of the mysteries are sacred but of even greater scope than those of the liturgical dramas; thus, there was the Mystery of the Old Testament, which ran for twenty-five days consecutively, and the Mystery of the Acts of the Apostles performed at Bourges in 1536, which lasted forty days.14 The performance was usually on a large outdoor stage, using the principle of “simultaneous décor,” that is, with all the scenes disposed in various places about the stage and each being used as required. Paradise was always placed at a higher level, and it was here that the singers and players were stationed, whence the hauntingly beautiful recurrent phrase in the stage directions, “Adoncques se doit resonner une melodye en Paradis” (Now shall a melody be sounded in Paradise). The middle level was for Earth, and there might be a still lower stage to represent Hell. The walls of Jerusalem, Herod’s palace, Noah’s Ark, the hill of Golgotha, the Garden of Eden, limbo, purgatory, and scores of other scenes were represented. All the miracles had to be shown visibly: descents and ascents of angels, Lucifer on a fire-breathing dragon, Aaron’s rod blossoming, the souls of Herod and Judas carried off by devils, water changed to wine, eclipses, earthquakes, the Deluge, even tortures and beheadings took place on the stage. The juxtaposition of sacred scenes and crude displays no longer gives the impression of naive piety, as in the liturgical dramas, but rather of almost blasphemous incongruity. The large number of characters and the grotesque, disorderly crowding of episodes make of the mysteries a typically Gothic spectacle, reminiscent of the sprawling confusion of incidents and personages in the medieval epics and romances. There were also comic insertions, improvised antics or farces, often of an indecent nature. Finally, the mysteries went so far as to permit mockery of the church and priests and the introduction of pagan deities on the stage. The awakened conscience of the church, together with the revival of classic ideals of the drama, eventually led to the condemnation of the mysteries on both moral and aesthetic grounds. By the end of the sixteenth century they were virtually extinct, though some remnants of the medieval love of profusion and grotesquerie survived in the operas and ballets of the seventeenth century.

Music in the mysteries was less extensive than in the liturgical dramas. In most cases its function was incidental, and since little of it has come down to us, we learn of its existence only by references in the stage directions and from other indirect sources. Hymns and other parts of the liturgy were sung, as in the Mystery of the Resurrection (fifteenth century), where all the spirits sing “Veni creator spiritus” at the moment when Christ descends into Hell.15 Most of these selections were probably simple plainsong, but occasionally there were pieces in polyphonic style. In the Mystery of the Passion (Anglers, 1486), the voice of God is represented by three singers, soprano, tenor, and bass—this doubtless being intended to symbolize the Trinity.16 Sometimes the angels in Paradise sing three-part motets, as in the Mystery of the Incarnation (Rouen, 1474). In addition to music of this kind, the mysteries included popular airs, in the singing of which the audience joined. In Germany, where the Nativity plays were especially cultivated, one such song was the well-known “In dulci jubilo.”17

There was also a considerable amount of instrumental music in the mysteries. Before the performance there would be a procession (monstre) through the town, with music by pipe and tabor. Entrances of important personages were announced by a silete, similar to the “flourish of trumpets” in Shakespeare. Instrumental music accompanied the procession of the actors to a different scene on the stage. Angels played concerts of harps—or rather pretended to play them—while musicians concealed behind the scenes furnished the music. Instruments were also played for dancing: in the Mystery of the Passion, Herod’s daughter dances a moresca to the accompaniment of a tambourine; in Italy we learn of morescas, galliards, pavanes, and many other dances in these spectacles, which frequently concluded with a general dance. For the monstre of the Mystery of the Acts of the Apostles, there was an orchestra of flutes, harps, lutes, rebecs, and viols. Trumpets, bucinae, bagpipes, cornemuses, drums, and organs are also mentioned; in the Mystery of the Passion, the march of Jesus to the temple is accompanied by “a soft thunder of one of the large organ pipes,” and in the Mystery of the Resurrection, the descent of the Holy Ghost is similarly signalized.18

There was at least one mystery in which music, instead of being merely incidental, was used throughout. This was the El misterio de Elche, a Spanish mystery of the late fifteenth or early sixteenth century, which had instrumental pieces, unaccompanied plainsong solos, and a number of three- and four-part choruses by the Spanish composers Antonio Ribera, David Perez, and Lluis Vich.19 This instance of continuous music in the mysteries is probably not unique. Some of the Italian sacre rappresentazioni and similar pieces of the fifteenth century seem to have been sung throughout. This play is performed annually on the feast of the Assumption in mid-August at the basilica of Santa Maria in Elche. It is staged in the nave of the church on a specially erected stage at the crossing. To allow the angel “to descend from a cloud in Heaven” and the soul of the Virgin “to ascend to Heaven,” a device known as an aracoeli is used.

The medieval liturgical dramas and mysteries, although they did not lead directly into the opera, are more than merely isolated precursors of the form. The Italian sacre rappresentazioni were the models from which the first pastoral dramas with music were derived. We shall have occasion later to see how the traditions and practices of such works manifest themselves in some of the operas of the seventeenth century. But their music was completely unsuited to modern dramatic expression. The immediate predecessors of the opera must be sought in the secular theater of the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

Secular Dramatic Music

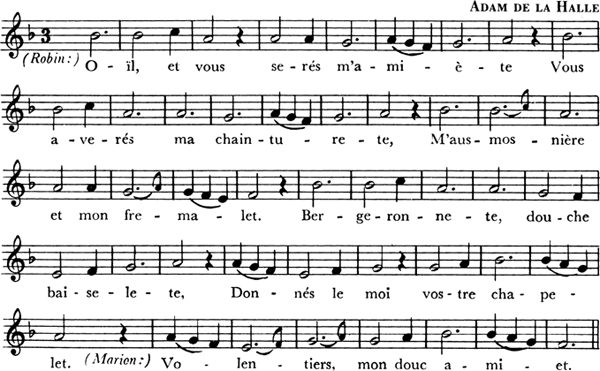

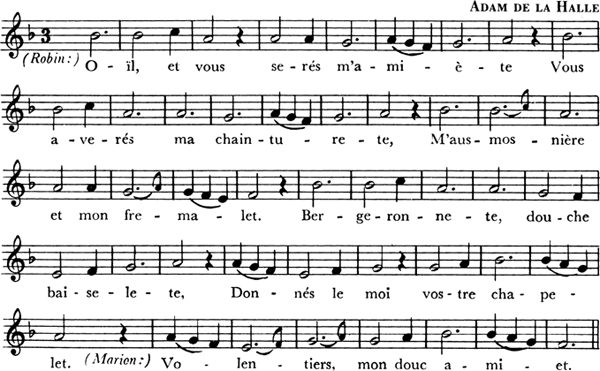

Aside from the dramas of antiquity, the earliest known secular play that used music extensively is Adam de la Halle’s Le Jeu de Robin et de Marion, probably performed at the court of the king of Naples in 1283 or 1284.20 Although this work is sometimes called the first opéra comique, it actually has no historical connection with the later genre, and indeed differs in no way from other pastourelles of its period, except that Adam chose to omit the customary narrative portions and make it simply a little pastoral comedy, in which the spoken dialogue is interspersed with a number of short songs or refrains, dances, and some instrumental music. It is probable that Adam himself wrote neither the words nor the music of the songs, but simply selected them from a current common repertoire.21 Their charmingly naive character is illustrated in example 2.1.

EXAMPLE 2.1 Le Jeu de Robin et de Marion

Le Jeu de Robin et de Marion is an early example of the use of chansons in a dramatic framework. Chansons, for the most part of popular nature and uncertain origin, were frequently inserted in morality plays, farces, sotties, and like entertainments of the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries in France.22

1. Leading works in English on this period include Chambers, The Medieval Stage; Young, The Drama of the Medieval Church (on liturgical dramas only); Hardison, Christian Rite and Christian Drama; Smoldon, The Music of the Medieval Church Dramas; Collins, Medieval Church Music-Dramas. See also Simon, ed., The Theatre of Medieval Europe: New Research in Early Drama; Dunn, ed., The Medieval Drama and Its Claudelian Revival; Mantzius, A History of Theatrical Art, vol. 2.

2. Cf. Stevens and Rastall, “Medieval Drama.”

3. It has been suggested that the term liturgical drama is not appropriate when applied to plays developed from paraliturgical material and tropes (passages added to the regular liturgy); however, since this term is well established, there seems little point in attempting to replace it by the more accurate designation of “ecclesiastical drama” or “church drama.”

4. Question: Whom do you seek in the tomb, O followers of Christ?

Response: Jesus of Nazareth who was crucified, O dwellers in heaven.

Response: He is not here, he has risen as was foretold; go, make known he has risen.

In some manuscripts, de sepulchro (from the tomb) is added after surrexit (he is risen). See, for example, the St. Gall MS. 339.

5. McGee, in “The Liturgical Placements of the Quem quaeritis Dialogue,” 5–6, defines the Collecta ceremony as a service “occurring before important liturgical ceremonies at a church known as a Collecta where congregations and celebrants assembled for a short ‘collect’ before processing to the stational church.” Cf. Hardison, “Gregorian Easter Vespers and Early Liturgical Drama”; Flanigan, “The Liturgical Context of the Quem quaeritis Trope.” Davidson, ed., Holy Week and Easter Ceremonies and Dramas.

6. Modern editions with music include Coussemaker, Drames liturgiques du moyen âge; G. Vecchi, Uffici drammatici padovani; Krieg, Das lateinische Osterspiel von Tours; Kühl, “Die Bordesholmer Marienklage”; Smits van Waesberghe, “A Dutch Easter Play”; Greenberg, ed., The Play of Daniel; Smoldon and Greenberg, eds., The Play of Herod; Hildegard of Bingen, Ordo Virtutum.

7. Coussemaker, Dramas liturgiques, ix.

8. This morality play predates by some two hundred years other extant works in the genre. See Potter, “The Ordo Virtutum: Ancestor of the English Moralities?”

9. Newman, ed., Voice of the Living Light, 171.

10. The monk Volmar, who served first as a teacher and then as a secretary for Hildegard, may have played the role of the Devil. Other candidates for this role include her nephew, Wezelin, whose copying of the Ordo Virtutum (found in the Risendkodex in the Hessische Landesbibliothek) provides the only reliable source for a modern edition. See Davidson, ed., The Ordo Virtutum of Hildegard of Bingen: Critical Studies.

11. Very few liturgical plays based upon personages in the Hebrew Scriptures were written before the beginning of the fourteenth century. See Fassler, “The Feast of Fools and Danielis Ludus.”

12. Charles Burney attended an outdoor production of this kind in a town north of Florence, where a popular mystery play based on the biblical story of David and Goliath was given in the town square. For his description, see the entry for September 4, 1770, in his Present State of Music in France and Italy, 245.

13. For the other Italian names for these pieces, and a general account of them in Italy, see D’Ancona, Origini del teatro italiano, 1:370ff; Becherini, “La musica nelle Sacre rappresentazioni Fiorentine”; and the examples in D’Ancona, Sacre rappresentazioni; Bartholomaeis, ed., Laude drammatiche; Bonfantini, Le sacre rappresentazioni italiane.

14. For a modern edition of The Mystery of the Old Testament, see Rothschild, Le Mistère du Viel Testament.

15. Jubinal, Mystères inédits du quinzième siècle, 2:339.

16. Cohen, Histoire de la mise en scène, 140.

17. Moser, Geschichte der deutschen Musik, 1:320; Hoffmann von Fallersleben, In dulci jubilo.

18. Cohen, Histoire de la mise en scène, 136, 159.

19. Cf. Pedrell, “La Festa d’Elche”; Trend, “The Mystery of Elche”; Shergold, A History of the Spanish Stage.

20. Modern editions of Le Jeu de Robin et de Marion have been edited by Coussemaker (1872), Langlois (1896), Cohen (1935), Varty (1960), and Gennrich (1962). See also Guy, Essai sur la vie et les oeuvres littéraires, and Axton, comp., Medieval French Plays.

21. Chailley, “La Nature musicale du Jeu de Robin et Marion.”

22. Brown, Music in the French Secular Theater, 1400–1550; Cohen, ed., Recueil de farces françaises inédites du XVe siècle.